About This Episode

Are we all living in a simulation inside our brains? Neil deGrasse Tyson and co-hosts Chuck Nice and Gary O’Reilly learn about the root of perception, if AI really is intelligent, and The Free Energy Principle with theoretical neuroscientist Karl Friston.

Discover the Free Energy Principle as a framework for understanding how the brain self-organizes and minimizes uncertainty about the world. Does the brain keep an internal model of the world that it continues to update? How does this principle relate to perception, decision-making, and the human experience? How does our brain, a blob of neurons locked inside a skull, make sense of the chaotic data it receives from the world?

Friston introduces us to “Active Inference,” the application of this principle, explaining how the brain samples the environment and updates its beliefs to create a cohesive understanding of reality. He discusses how psychiatric disorders, like schizophrenia, can arise when there’s a mismatch between the brain’s internal model and external reality, and how this theory could one day help explain and treat these conditions.

We explore how these ideas from neuroscience can be used in artificial intelligence and large language models, discussing the limits of machine learning. Can AI truly possess intelligence? Or is it merely following pre-programmed paths, unable to build the complex internal models humans use to navigate the world? Can AGI– artificial general intelligence– ever be achieved in a machine? What do we even mean when we say AGI? Does an objective reality even exist?

Thanks to our Patrons Timothy Ecker, Jason Griffith, Evan Lee, Marc, Christopher Young, ahoF3Hb9m, Steven Kraus, Dave Hartman, Diana Todd, Jeffrey Shulak MD, Susan Summers, Kurt A Goebel, Renee Harris, Damien, Adam Akre, Kyle Marston, Gabriel, Bradley Butikofer, Patrick Hill, Cory Alan, and Micheal Gomez for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTSo guys, I was delighted to learn all the ways that principles of physics could be borrowed by neuroscientists to try to understand how our brain works.

Because at the end of the day, there’s physics and everything else is just opinion.

If you say so yourself.

I love how you get to say that.

But it’s the physics of intelligence.

The physics of neuroscience is really what that is about.

As you’ve educated us, the physics is in everything.

Yes.

You just don’t think of it as being in neuroscience.

Yeah, because we’ve compartmentalized what people do as professional scientists into their own textbook and their own journals and their own departments at universities.

At the end of the day, we are one.

It’s all physics, people.

At the end, that’s the lesson we learn.

Coming up, all that and more on StarTalk Special Edition.

Welcome to StarTalk.

Your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk Special Edition.

Neil deGrasse Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist.

And if this is special edition, you know it means we’ve got not only Chuck Nice.

Chuck, how you doing, man?

Hey, buddy.

Always good to have you there as my co-host.

And we also have Gary O’Reilly, a former soccer pro, sports commentator.

What’s up with the crowd cheering him on?

Yeah, that’s the crowd at Tottenham.

Tottenham, yeah.

Crystal Palace, they’re all.

Anytime you mention my name in this room, there’s a crowd effect.

Gary, you know, with special edition, what you’ve helped do with this branch of StarTalk is focus on the human condition and every way that matters to it.

The mind, body, soul, it would include AI, a mechanical augmentation to who and what we are.

Robotics.

So this just fits right in to that theme.

So take us where you need for this episode.

In the age of AI and machine learning, we as a society and naturally as StarTalk are asking all sorts of questions about the human brain, how it works and how we can apply it to machines.

One of these big questions being perception.

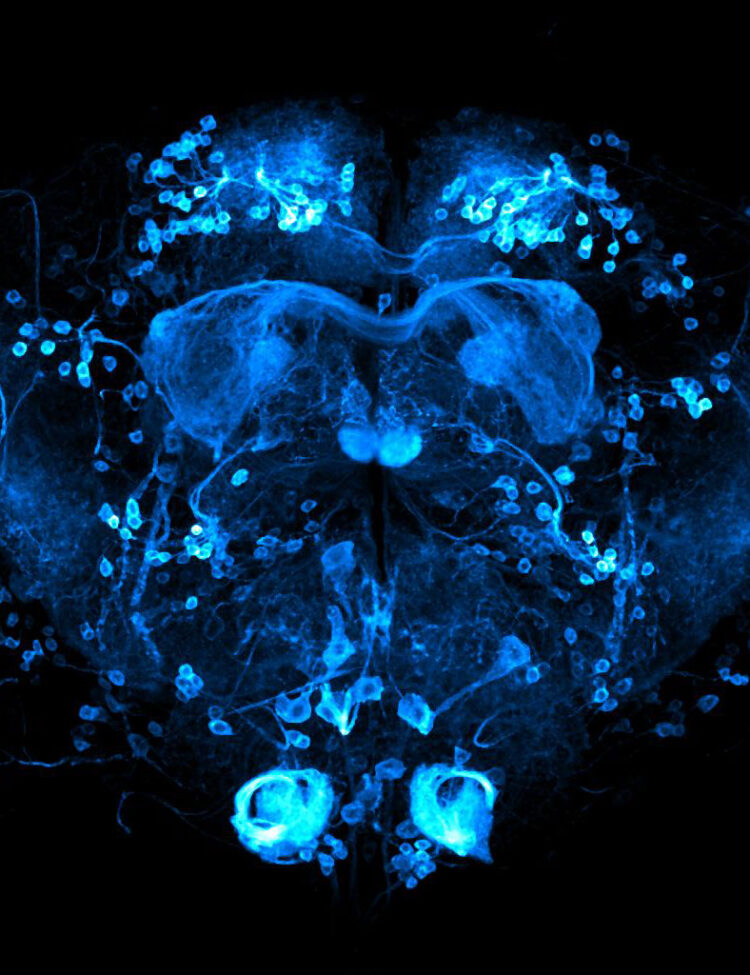

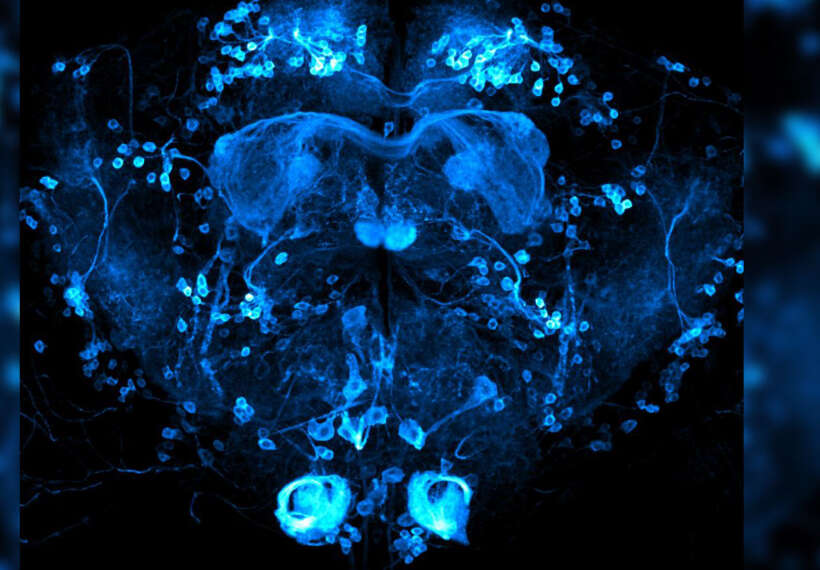

How do you get a blob of neurons?

I think that’s a technical term.

That’s technical for sure.

Yeah.

In your skull to understand the world outside.

Our guest, Karl Friston, is one of the world’s leading neuroscientists and an authority on neuroimaging, theoretical neuroscience and the architect of the free energy principle.

Using physics-inspired statistical methods to model neuroimaging data, that’s one of his big successes.

He’s also sought after by the people in the machine learning universe.

Now, just to give you a little background on Karl, a neuroscientist and theoretician at University College London, where he is a professor, studied physics and psychology at Cambridge University in England.

An inventor of the statistical parametric mapping used around the world and neuroimaging plus many other fascinating things.

He is the owner of a seriously impressive array of honors and awards which we do not have time to get into.

And he speaks Brit.

Yes.

So he’s evened this out.

There’s no more picking on the Brit because there’s only one of them.

Okay.

Karl Friston, welcome to StarTalk.

Well, thank you very much for having me.

I should just point out I can speak American as well.

Please don’t.

Karl, that takes a certain level of illiteracy that I’m sure that you don’t possess.

Yeah, please don’t stoop to our level.

Yeah.

So let’s start off with something.

Is it a field or is it a principle or is it an idea that you pioneered, which is in our notes known as the free energy principle?

I come to this as a physicist and there’s a lot of sort of physics-y words that are floating or orbiting your work.

And so in physics, they’re very precisely defined.

And I need to know how you are using these terms and in what way they apply.

So let’s just start off.

What is the free energy principle?

Well, as it says on the tin, it is a principle and in the spirit of physics, it is therefore a method.

So it’s just like Hamilton’s principle of least action.

So it’s just a prescription, a formal mathematical prescription of the way that things behave that you can then use to either simulate or reproduce or indeed explain the behavior of things.

So you might apply the principle of least action, for example, to describe the motion of a football.

The free energy principle has a special domain of application.

It talks about the self-organization of things where things can be particles, they can be people, they can be populations.

So it’s a method really of describing things that self-organize themselves into a characteristic state.

Very cool.

So why give it this whole new term?

We’ve all read about or thought about or seen the self-organization of matter.

Usually, there’s a source of energy there available though, or it reaches sort of a minimum energy because that’s what it, it’s a state that it prefers to have.

You know, so a ball rolls off a table onto the ground, it doesn’t roll off the ground onto the table.

So it seeks the minimum place.

And my favorite of these is the box of morning breakfast cereal.

And it will always say some settling of contents may have occurred.

Yeah.

And you open up and it’s like two-thirds full.

Yeah, two-thirds of powder.

You get two-thirds of crushed shards of cornflakes, your crust flakes.

So it’s finding sort of the lowest place in the Earth’s gravitational potential.

So why the need for this new term?

Well, it’s an old term.

I guess, again, pursuing the American theme, you can trace this kind of free energy back to Richard Feynman, probably his PhD thesis.

So he was trying to deal with the problem of describing the behavior of small particles and invented this kind of free energy as a proxy that enabled him to evaluate the probability that a particle would take this path or that path.

So exactly the same maths now has been transplanted and applied not to the movement of particles but to what we refer to as belief updating.

So it’s lovely you should introduce this notion of nature finding its preferred state that can be described as rolling downhill to those free energy minima.

This is exactly the ambition behind the free energy principle, but the preferred states here are states of beliefs or representations about a world in which something, say you or I exist.

So this is the point of contact with machine learning and artificial intelligence.

So the free energy is not a thermodynamic free energy.

It is a free energy that scores a probability of your explanation for the world in your head being the right kind of explanation.

And you can now think about our existence, the way that we make sense of the world and our behavior, the way that we sample that world as effectively falling downhill to that, settling towards the bottom, but in an extremely itinerant way, in a wandering way as we go through our daily lives at different temporal scales.

It can all be described effectively as coagulating at the bottom of the cereal packet in our preferred states.

Wow, so you’re, again, I don’t want to put words in your mouth that don’t belong there.

This is just my attempt to interpret and understand what you just described.

You didn’t yet mention neurons, which are the carriers of all of this, or the transmitters of all of this thoughts and memories and interpretations of the world.

So when you talk about the pathways that an understanding of the world takes shape, do those pathways track the nearly semi-infinite connectivity of neurons in our brains, and so you’re finding what the neuron will naturally do in the face of one stimulus versus another?

That’s absolutely right.

In fact, technically, you can describe neuronal dynamics, the trajectory or the path of nerve cell firing, exactly as performing a gradient descent on this variational free energy.

That is literally true, but I think more intuitively, the idea you’ve just expressed, which is you can trace back possibly to the early days of cybernetics in terms of the good regulator theorem.

The idea here is that to be well adapted to your environment, you have to be a model of that environment.

In other words, to interface and interact with your world through your sensations, you have to have a model of the causal structure in that world.

That causal structure is thought to be literally embedded in the connectivity among your neurons within your brain.

My favorite example of this would be the distinction between where something is and what something is.

In our universe, a certain object can be in different positions.

If you told me what something is, I wouldn’t know where it was.

Likewise, if you told me where something was, I wouldn’t know what it was.

That statistical separation, if you like, is literally installed in our anatomy.

So, you know, there are two screens in the back of the brain, one dealing with where things are and one stream of connectivity dealing with what things are.

However, we are pliable enough, though.

Of course, I’m not pushing back.

I’m just trying to further understand.

We’re pliable enough, though, that if you were to say, go get me the thing, okay, and then you give me very specific coordinates of the thing, I would not have to know what the thing is, and I would be able to find it, even if there are other things that are there.

Yep.

And that speaks to something which is quite remarkable about ourselves that we actually have a model of our lived world that has this sort of geometry that can be navigated because our presupposes that you’ve got a model of yourself moving in a world, and you know the way that your body works.

I’m tempted here to bring in groins, but I don’t know why.

Chuck injured his groin a few days ago, and that’s why that’s all he’s been talking about.

Karl, well played.

We’ve all heard about it since.

Karl, I hear the term active inference, and then I hear the term Bayesian active inference.

Let’s start with active inference.

What is it?

How does it play a part in cognitive neuroscience?

Active inference, I think, most simply put, would be an application of this free energy principle we’re talking about.

So it’s a description or applying the maths to understand how we behave in a sentient way.

So active inference is meant to emphasize that perception, read as unconscious inference in the spirit of Helmholtz, depends upon the data that we actively solicit from the environment.

So what I see depends upon where I am currently looking.

So this speaks to the notion of active sensing.

You went a little fast.

I’m sorry, man.

I’m trying to keep up here, but you went a little fast there, Karl.

You talked about perception being an inference that is somehow tied to the subconscious.

But can you just do that again, please?

And just to be clear, he’s speaking slowly.

Exactly.

So it’s not that he’s going fast.

No.

Is that you are not keeping up.

Well, listen, I don’t have a problem.

Okay.

I have no problem not keeping up, which is why I have never been left behind, by the way.

I have no problem keeping up because I go, wait a minute.

So anyway, can you just break that down a little bit for me?

Sure.

I was trying to speak at a New York pace.

My apologies.

I’ll revert to London.

Okay.

So let’s start at the beginning.

Sense making, perception.

How do we make sense of the world?

We are locked inside of, our brains are locked inside a skull.

It’s dark in there.

There’s no, you can’t see other than what information is conveyed by your eyes or by your ears or by your skin, your sensory organs.

So you have to make sense of this unstructured data coming in from your sensory organs, your sensory epithelia.

How might you do that?

The answer to that or one answer to that can be traced back to the days of Plato through Count and Helmholtz.

So Helmholtz brought up this notion of unconscious inference.

Sounds very glorious, but very, very simply, it says that if inside your head, you’ve got a model of how your sensations were caused, then you can use this model to generate a prediction of what you would sense if this was the right cause, if you got the right hypothesis.

And if what you predict matches what you actually sense, then you can confirm your hypothesis.

So this is where inference gets into the game.

It’s very much like a scientist who has to use scientific instruments, say microscopes or telescopes, in order to acquire the right kind of data to test her hypotheses about the structure of the universe, about the state of affairs out there, as measured by her instruments.

So this can be described, this sort of hypothesis testing, putting your fantasies, your hypotheses, your beliefs about the state of affairs outside your skull to test by sampling data and testing hypotheses.

Because this is just inference.

So this is where inference gets into the game.

These are micro steps on route to establishing an objective reality.

And there are people for whom their model does not match a prediction they might make for the world outside of them.

And they would be living in some delusional, some world that you cannot otherwise agree to what is objectively true.

And that would be, that would then be an objective measure of insanity or some other neurological disconnect.

Yeah.

Yeah, really, no?

I mean, is it really?

Well, if you project your own fantastical world into reality, and you know it doesn’t sit, but it’s what you want, then that’s a dysfunction.

You’re not working with, you’re working against.

We live in a time now where that fantastical dysfunction, actually has a place.

And talk to James Cameron for just a little bit, and you’ll see that that fantastical dysfunction was a world building creation that we see now as a series of movies.

So is it really so aberrant that it’s a dysfunction, or is it just different?

Well, I think he’s trying to create artistically, rather than impose upon.

Yeah, so Karl, if everyone always received the world objectively, would there be room for art at all?

Ooh, that was a good question.

Yeah, it really was.

Well done, sir.

I’m going to say, I think I was the inspiration for that question.

Yes, Chuck inspired that question.

So there’s a role for each side of this, the perceptive reality, correct?

No, absolutely.

So just to pick up on a couple of those themes, but that last point was, I think, quite key.

It is certainly the case that one application of or one use of active influence is to understand psychiatric disorders.

So you’re absolutely right.

When people, a model of their lived world is not quite apt for the situation in which they find themselves.

Say something changes, say you lose a loved one.

So your world changes.

So your predictions and the way that you sort of navigate through your day either socially or physically is now changed.

So your model is no longer fit for purpose for this world.

But as Chuck was saying before, the brain is incredibly plastic and adaptive.

So what you can do is you can use the mislatch between what you predict is going to happen and what you actually sense to update your model of the world.

Before I was saying that this is a model that would be able to generate predictions of what you would see under a particular hypothesis or fantasy.

Just to make a link back to AI, this is generative AI.

It’s intelligent forecasting prediction under a generative model that is entailed exactly by the connectivity that we were talking about before in the brain.

It’s the free energy principle manifesting when you readjust to the changes and it’s finding the new roots that are presumably the more accurate your understanding of your world, the lower is that free energy state or is it higher or lower?

That is absolutely right.

Actually, technically, if you go into the cognitive neurosciences, you will find a big move in the past 10 years towards this notion of predictive processing and predictive coding, which again just rests upon this meme that our brains are constructive organs generating from the inside out predictions of the sensorium.

Then the mismatch is now a prediction error.

That prediction error is then used to drive the neurodynamics that then allow for this revising or updating my beliefs, such that my predictions now are more accurate and therefore the prediction error is minimized.

The key thing is, to answer your question technically, the gradients of the free energy that drive you downhill just are the prediction errors.

So, when you minimize your free energy, you’ve squashed on the prediction errors.

Absolutely.

Excellent.

You’re not going to roll uphill unless there’s some other change to your environment.

So if we think back to early mankind and the predictability.

So I’m walking along, I see a lion in the long grass.

What do I start to predict?

If I run up a tree high enough, that lion won’t get me.

But if I run along the ground, the lion’s probably gonna get.

Is this kind of evolutionary that we’ve borne for survival?

Yep.

Or have I misinterpreted this completely?

No, no, I think that’s an excellent point.

Well, let’s just think about what it means to be able to predict exactly what you would sense in a given situation and thereby predict also what’s going to happen next.

If you can do that with your environment and you’ve reached the bottom of the serial packet and you’ve minimized your free energy, minimized your prediction errors, you now can fit the world.

You can model the world in an accurate way.

That just is adaptive fitness.

So if you look at this process now as unfolding over evolutionary time, you can now read the variational free energy or its negative as adaptive fitness.

So that tells you immediately that evolution itself is one of these free energy minimizing processes.

It is also, if you like, testing hypotheses about the kind of organisms of its environment, the kind of creatures that will be a good fit for this particular environment.

So you can actually read natural selection as, in statistics, will be known as Bayesian model selection.

So you are effectively inheriting inferences or learning transgenerationally in a way that’s minimizing your free energy, minimizing your prediction errors.

So things that get eaten by lions don’t have the ability to promulgate themselves through to the next generation.

So that everything ends up at the bottom of the cereal packet avoiding lions.

Because those are the only things that can be there, because the other ones didn’t minimize their free energy.

Yeah, unless, Gary, you made babies before you said, I wonder if that’s a lion in the bushes.

Right.

But if they’ve got my genes, then there’s a lion with their name on it.

That’s exactly right.

I want to share with you one observation, Karl.

And then I want to hand back to Gary, because I know he wants to get all in the AI side of this.

I remembered one of the books by Douglas Hofstadter.

It might have been Gödel Escher Bach, or he had a few more that were brilliant explorations into the mind and body.

In the end of one of his books, he had, it was an appendix, I don’t remember, a conversation with Einstein’s brain.

And I said to myself, this is stupid.

What does this even mean?

And then he went in and described the fact that imagine Einstein’s brain could be preserved at the moment he died.

And all the neurosynaptic elements are still in place.

And it’s just sitting there in a jar.

And you ask a question, and the question goes into his ears, gets transmitted into the sounds that trigger neurosynaptic firings.

It just moves through the brain, and then Einstein then speaks an answer.

And the way that setup was established, it was like, yeah, I can picture this sometime in the distant future.

Now, maybe the modern version of that is you upload your consciousness, and then you’re asking your brain in a jar, but it’s not biological at that point.

It’s in silicon.

But what I’m asking is the information going into Einstein’s brain in that thought experiment, presumably trigger his thoughts and then his need to answer that question, because it was posed as a question.

Could you just comment on that exercise, the exercise of probing a brain that’s sitting there waiting for you to ask it a question?

I mean, it’s a very specific and interesting example of the kind of predicted processing that we are capable of, because we’re talking about language and communication here.

And just note the way that you set up that question provides a lovely segue into large language models.

But note also that it’s not the kind of embodied intelligence that we were talking about in relation to active inference, because the brain is in a body, the brain is embodied.

Most of what the brain is actually in charge of is moving the body or secreting.

In fact, those are the only two ways you can change the universe.

You can either move a muscle or secrete something.

There is no other way that you can affect the universe.

So this means that you have to deploy your body in a way to sample the right kind of information that makes your model as apt or as adaptive as possible.

Well, so Chuck, did you hear what he said?

It means you cannot bend the spoon with your brain.

Right.

So I’ll let you go.

Just to clarify.

Okay.

So what I was trying to hint at, because I suspect it’s going to come up in a conversation, that there’s, I think, a difference between a brain and a vat or a large language model that is the embodiment of lots of knowledge.

So one can imagine, say, a large language model being a little bit like Einstein’s brain, but Einstein plus 100, possibly a million other people, and the history of everything that has been written, that you can probe by asking it questions.

And in fact, there are people whose entire career is now prompt engineers.

AI prompts.

It’s funny, the people who program AI then leave that job to become prompt.

The people who are responsible for creating the best prompts to get the most information back out of AI.

So it’s a pretty fascinating industry that they’ve created their own feedback loop that benefits them.

And now you can start to argue, where is the intelligence?

Is it in the prompt engineer?

As a scientist, I would say that’s where the intelligence is.

That’s where the sort of sensing behavior is.

It’s asking the questions, not producing the answer.

That’s the easy bit.

It’s certainly asking, queering the world in the right way.

And just notice, what are we all doing?

What is your job?

Is it asking the right questions?

Karl, can I ask you this, please?

Could active inference cause us to miss things that do happen?

And secondly, does deja vu fit into this?

Yes, and yes, in a sense, active inference is really about missing things that are measurable or observable in the right kind of way.

So another key thing about natural intelligence and be a good scientist, just to point out that sort of noting the discovering infrared, that’s an act of creation, that is art.

So where did that come from?

From somebody’s model about the structure of electromagnetic radiation.

So I think just to pick up on a point we missed earlier on, creativity and insight is an emergent property of this kind of question and answer in an effort to improve our models of our particular world.

Coming back to missing stuff, it always fascinates me that the way that we can move depends upon ignoring the fact we’re not moving.

So I’m talking now about a phenomena in cognitive science called sensory attenuation.

And this is the rather paradoxical, or at least counterintuitive phenomenon.

That in order to initiate a movement, we have to ignore and switch off and suppress any sensory evidence that we’re not currently moving.

And my favorite example of this is moving your eyes.

So if I asked you to sort of track my finger as I moved it across the screen and you moved your eyes very, very quickly.

While your eyes are moving, you’re actually not seeing the optic flow that’s being produced.

Because you are engaging something called saccadic suppression.

And this is a reflection of the brain very cleverly knowing that that particular optic flow that I have induced is fake news.

So the ability to ignore fake news is absolutely essential for a good navigation and movement of our world.

If it’s fake, we’re just irrelevant to the moment.

If it’s the New York Times, it’s definitely fake.

Fake news.

But it’s not so much fake, it’s just not relevant to the task at hand.

Isn’t that a different notion?

It’s a subtle one.

For the simplicity of the conversation, then I’m reading fake as irrelevant, imprecise.

It’s like it’s unusable, so your brain is just throwing it out, basically.

Nothing to see here, so get rid of that.

So Neil, this is in your backyard rather more than mine, but isn’t this where the matrix pretext kind of fits in, that our perception might differ from what’s actually out there, and then perception can be manipulated or recreated?

Well, I think Karl’s descendants will just put us all in a jar.

That’s the way he’s talking.

Karl, what does your laboratory look like?

It’s full of jars.

Yes.

Well, there are several pods, and we have one waiting for you.

Yeah, in the film The Matrix, of course, which came out in 1999, about 25 years ago, a quarter century ago.

It’s hard to believe.

What?

It was a very candid sense that your brain’s reality is the reality you think of and understand, and it is not receiving external input.

All that your brain is constructing is detached from what’s exterior to it.

And if you’ve had enough lived experience or maybe in that future that they’re describing, the brain can be implanted with memory.

It reminds me, what’s that movie that Arnold Schwarzenegger is in about Mars?

Total Recall.

Total Recall.

Thank you.

Get your ass to Mars.

Instead of paying thousands of dollars to go on vacation, they would just implant the memories of a vacation in you and bypassing the sensory conduits into your brain.

Of course, these are movies and they’re stories and it’s science fiction.

How science fiction-y is it really?

Well, I certainly think that the philosophy behind, I think, probably both Total Recall, but particularly The Matrix, I think that’s very real and very current.

Just going back to our understanding people with psychiatric disorders or perhaps, you know, people who have odd views, world views, that to understand that the way that you make sense of the world can be very different from the way I make sense of the world, dependent on my history and my predispositions and my prize, what I have learned thus far.

And also the information that I select to attend to.

So just pursuing this theme of ignoring 99% of all the sensations for example, Chuck, are you thinking about your groin at the moment?

I would guarantee you’re not.

Yet it is generating sensory impulses from the nerve endings.

But you at this point in time were not selecting that.

So the capacity to select is, I think, a fundamental part of intelligence and agency.

Because to select means that you are not attending to or selecting 99% of the things that you could select.

So I think the notion of selection is a hallmark of truly intelligent behavior.

Yeah, are you analogizing that to large language models in the sense that it could give you gibberish, it could find crap anywhere in the world that’s online, but because you prompted it precisely, it is gonna find only the information necessary and ignore everything else?

Yes and no, but that’s a really good example.

So the yes part is the characteristic bit of architecture that makes large language models work.

Certainly those that are implemented using transformer architectures are something called attention heads.

So it is exactly the same mechanism, the same basic mechanics that we were talking about in terms of attention selection that makes transformers work.

So they select the recent past in order to predict the next word.

That’s why they work, to selectively pick out something in the past, ignore everything else to make them work.

When you talk about that probability in an LLM, that probability is a mathematical equation that happens for like every single letter that’s coming out of that model.

So it is literally just giving you the best probability of what is going to come next.

Okay?

Whereas when we perceive things, we do so from a world view.

So for an LLM, if you show it a picture of a ball with a red stripe that’s next to a house, okay?

And say that’s a ball and then show it a picture of a ball in the hands of little girl who’s bouncing it.

It’s going to say, all right, that might be a ball.

That may not be a ball.

Whereas if you show even a two year old child, this is a ball and then take that ball and place it in any circumstance, the baby will look at it and go, fall, fall.

So there is a difference in the kind of intelligence that we’re talking about here.

Yeah, I think that’s spot on.

That’s absolutely right.

And that’s why I said yes and no.

So that kind of fluency that you see in large language models is very compelling and it’s very easy to give the illusion that these things have some understanding or some intelligence, but they don’t have the right kind of generative model underneath to be able to generalize and recognize a ball in different contexts like the way that we do.

Well, it would if it was set up correctly.

And that set up is no different from you looking at reading the scene.

I mean, a police officer does that busting into a room.

You know, who’s the perpetrator, who’s not, before you shoot.

There’s an instantaneous awareness factor that you have to draw from your exterior stimuli.

And so, because you know, I’m reminded of here, Karl, I saw one of these New Yorker style cartoons, where there are two dolphins swimming in one of these water, you know, parks, right?

And so, they’re in captivity.

But the two dolphins are swimming and one says to the other, of the person walking along the pool’s edge, those humans, they face each other and make noises, but it’s not clear they’re actually communicating.

And so, who are we to say that the AI large language model is not actually intelligent if you cannot otherwise tell the difference?

Who cares how it generates what it is?

If it gets the result that you seek, you’re going to say, oh, well, we’re intelligent and it’s not?

How much of that is just human ego speaking?

Well, I’m sure it is human ego speaking, but in a technical sense, I think.

Okay, there’s a loophole, you’re saying, because I’m not going to say that bees are not intelligent when they do their waggle dance, telling other bees where the honey is.

I’m not going to say termites are not intelligent when they build something a thousand times bigger than they are, when they make termite mounds and they all cooperate.

I’m fatigued by humans trying to say how special we are relative to everything else in the world that has a brain.

When they do stuff, we can’t.

Let me ask you then.

What’s the common theme between the termite and the bee and the policeman reading the scene?

What do they all have in common?

All of those three things move, whereas the large language model doesn’t.

Doesn’t.

That brings us back to this action, the active part of active inference.

So, the note to the question about large language models and attention was that the large language models are just given everything.

They’re given all the data.

There is no requirement upon them to select which data are going to be most useful to learn from.

And therefore, they don’t have to build expressive, fit for purpose world models or generative models.

Whereas, your daughter would, the two-year-old daughter playing with the beach ball would have to by moving and selectively reading the scene, by moving her eyes, by observing her body, by observing balls in different contexts, build a much deeper, appropriate world or generative model that would enable her to recognize the ball in this context and that context and ultimately tell her father, I’m playing with a ball.

So, we had a great show with Brett Kagan, who mentioned your free energy principle, and in his work creating computer chips out of neurons, what people call organoid intelligence, what he was calling synthetic biological intelligence.

And that’s in our archives.

In our recent archives, actually.

Recent archives, yeah.

Do you think the answer to AGI is a biological solution, a mechanical solution, or a mixture of both?

And remind people what AGI is?

Artificial general intelligence.

I know that’s what the words stand for, but what is it?

You’re not asking me for the answer.

Don’t ask me either.

I’ve been told off for even using the acronym anymore, because it’s so ill-defined, and people have very different readings of it.

So open AI has a very specific meaning for it.

If you talk to other theoreticians, they would represent it.

And I think what people are searching for is natural intelligence.

Gary, you know, it answered your question.

Do we have to make a move towards bi-mimetic, neuromorphic, natural kinds of instantiation of intelligent behavior?

Yes, absolutely.

But Chuck, just coming back to your previous theme, notice we’re talking about behaving systems.

Systems that act and move and can select and do their own data mining in a smart way, as opposed to just ingesting all the data.

So what I think people mean when they talk about super intelligence or generalized AI or artificial intelligence, they just mean natural intelligence.

They really mean us.

It’s our brain.

Our brain, if you want to know what AGI is, it’s our brain.

You know, and the way…

If it was actually our brain, it would be natural stupidity.

Well, that too.

Our brain without the stupidity.

That’s really what it is.

So back in December 22, you dropped a white paper titled Designing Ecosystems of Intelligence from First Principles.

Now, is this a road map for the next 10 years or beyond or to the terminate, ultimate destination?

And then somewhere along the line, you discussed the thinking behind a move from AI to IA, an IA standing for intelligent agents, which seems a lot like moving towards the architecture for sentient behavior.

Have I misread this in any way?

No, you’ve read that perfectly.

So that white paper was written with colleagues in industry, particularly versus AI, exactly the kind of road map that those people who were committed to a future of artificial intelligence that was more sustainable, that was explicitly committed to a move to natural intelligence and all the biomimetic moves that you would want to make, including implementations on neuromorphic hardware, quantum computation of photonics, always efficient approaches that would be sustainable in the sense of climate change, for example.

But also speaking to Chuck’s notion about efficiency.

Efficiency is also, if you like, bait into natural intelligence in the sense that if you can describe intelligent behavior as this falling downhill, pursuing free energy gradients, minimizing free energy, getting to the bottom of the serial packet, you’re doing this via a path of least action.

That is the most efficient way of doing it.

Not only informationally, but also in terms of the amount of electricity you use and the carbon footprint you leave behind.

From the point of view of sustainability, it’s important we get this right.

Part of the theme of that white paper was saying there is another direction of travel.

We are away from large language models.

Large is in the title.

It’s seductive, but it’s also very dangerous.

It shouldn’t be large.

It should be the size of a bee.

So to do it biologically, you should be able to do it much more efficiently.

And of course, the meme here is that our brains work on 20 watts, not 20 kilowatts.

And we do more than any large language model.

We have low-energy intelligence.

We do.

Efficient.

I guess that’s a way to say it.

I’ve seen you quoted, Karl, as saying that we are coming out of the age of information and moving into the age of intelligence.

If that’s the case, what is the age of intelligence going to look like?

Or have we already discussed that?

Well, I think we’re at its inception now, just in virtue of all the wonderful things that are happening around us and the things that we are talking about.

We’re asking some of the very big questions about what is happening and what will happen over the next decade.

I think part of the answer to that lies in your previous nod to the switch between AI and IA.

So IA brings agency into play.

So one deep question would be, is current generative AI an example of agentic?

Is it an agent?

Is a large language model an agent?

And if not, then it can’t be intelligent.

And certainly can’t have generalized intelligence.

So what is definitive of being an agent?

I put that out there as a question, half expecting a joke.

I’ve got Agent Smith in my head.

If anyone can take that and run with it.

Well, there you go.

It’s right about now where you hear people commenting on the morality of a decision and whether a decision is good for civilization or not.

And everybody’s afraid of AI achieving consciousness and just declaring that the world will be better off without humans.

And I think we’re afraid of that because we know it’s true.

Yeah, I was going to say, we’ve already come to that conclusion.

That’s the problem.

OK, Karl, is consciousness the same as self-awareness?

Yeah, there are lots of people who you could answer that question of and get a better answer.

I would say the purpose of this conversation, probably not.

No, I think to be conscious, certainly to be sentient and to behave in a sentient kind of way would not necessarily imply that you knew you were a self.

I’m pretty sure that a bee doesn’t have self-awareness, but it still has sentience, it still experiences, has experiences and has plans and communicates and behaves in an intelligent way.

You could also argue that certain humans don’t have self-awareness of a fully developed sort.

I’m talking about very severe psychiatric conditions.

I think self-awareness is a gift of a particular very elaborate, very deep generative model that not only entertains the consequences of my actions, but also entertains the fantasy or hypothesis that I am an agent of the I am self and can be self-reflective in a metacognitive sense.

I think I’d differentiate between self-aware and simply being capable of sentient behavior.

Wow, that is great.

Let me play skeptic here for a moment.

Mild skeptic.

You’ve described, you’ve accounted for human decision making and behavior with a model that connects the sensory conduits between what’s exterior to our brain and what we do with that information as it enters our brain.

And you’ve applied this free energy gradient that this information follows.

That sounds good.

It all sounds fine.

I’m not going to argue with that.

But how does it benefit us to think of things that way?

Or is it just an after the fact pastiche on top of what we already knew was going on, but now you put fancier words behind it?

Is there predictive value to this model?

Or is the predictivity in your reach, because when you assume that’s true, you can actually make it happen in the AI marketplace?

Yeah, I think that that’s the key thing.

When I’m asked that question, or indeed when I asked that question of myself, I applied to things like Hamilton’s principle of least action.

Why is that useful?

Well, it becomes very useful when you’re actually building things.

It becomes very useful when you’re simulating things.

It becomes useful when something does not comply with Hamilton’s principle of least action.

So just to unpack those directions that travel in terms of applying the free energy principle, that means that you can write down the equations of motion.

And yeah, you can simulate self-organization that has this natural kind of intelligence, this natural kind of sentient behavior.

You can simulate it in a robot.

In an artifact, in a terminator, should you want to.

Although strictly speaking, that would not be compliant with the free energy principle.

But you can also simulate it in silico and make digital twins of people and choices and decision making and sense making.

Once you can simulate, you can now use that as an observation model for real artifacts and start to phenotype, say, people with addiction or say, people who are very creative or say, people who had schizophrenia.

So if you can cast a barren inference or false inference, believing things are present when they’re not or vice versa, as an inference problem and you know what the principles of sense making and inference are, and you can model that in a computer.

You can now go to stamp it in which you can now, not only phenotype by adjusting the model to match somebody’s observed behavior, but now you can go and apply synthetic drugs or do brain surgery in silico.

So there are lots of practical applications of knowing how things work, or when I say things work, how things behave.

That presumes that your model is correct.

For example, just a few decades ago, it was presumed, and I think no longer so, that our brain functioned via neural nets, neural networks where it’s a decision tree and you slide down the tree to make an ever more refined decision.

On that assumption, we then mirrored that in our software to invoke neural net decision making in my field, in astrophysics.

How do we decide what galaxy is interesting to study versus others?

In the millions that are in the data set.

You just put it all into a neural net that has parameters that select for features that we might in the end of that effort determine to be interesting.

We still invoke that, but I think that’s no longer the model for how the brain works.

But it doesn’t matter, it’s still helpful to us.

You’re right, and honestly that is now how AI is organized around the new way that we see the brain working.

Yeah, so, and why is the brain the model of what should be emulated?

The human physiological system is rife with baggage, evolutionary baggage.

Much of it is of no utility to us today except sitting there available to be hijacked by advertisers or others who will take advantage of some feature we had 30,000 years ago when it mattered for our survival, and today it’s just dangling there waiting to be exploited.

So a straight answer to your question, the free energy principle is really a description or a recipe for self-organization of things that possess a set of preferred or characteristic states coming right back to where we started, which is the bottom of the cereal packet.

If that’s where I live, if I want to be there, that’s where I’m comfortable, then I can give you a calculus that will for any given situation, prescribe the dynamics and the behavior and the sense making and the choices to get you to that point.

It is not a prescription for what is the best place to be or what the best embodied form of that being should be.

In saying that if you exist and you want to exist in a sustainable way, where it could be a speech, it could be a meme.

In a given environment, yes, in a given setting.

It’s all about the relationship.

That’s a really key point.

So the variational free origin that we’ve been talking about, the prediction error, is a measure of the way that something couples to its universe or to its world.

It’s not a statement about a thing in isolation.

It’s the fit.

Again, if you just take the notion of prediction error, there’s something that’s predicting and there’s something being predicted.

So it’s all relational.

It’s all observational.

It’s a measure of adaptive fitness.

That’s an important clarification, yes.

Karl, could you give us a few sentences on Bayesian inference?

That’s a new word to many people who even claim to know some statistics.

That’s a way of using what you already know to be true to help you decide what’s going to happen next.

Are there any more subtleties to a Bayesian inference than that?

I think what you just said captures the key point.

It’s all about updating.

It’s a way of describing inference by which people just mean estimating the best explanation probabilistically, a process of inference that is ongoing.

Sometimes this is called Bayesian belief updating, updating one’s belief in the face of new data.

How do you do that update in a mathematically optimal way?

You simply take the new evidence, the new data, you combine it using Bayes’ rule with your prior beliefs established before you saw this new data to give you a belief afterwards, sometimes called a posterior belief.

Because otherwise you would just come up with a hypothesis, assuming you don’t know anything about the system, and that’s not always the fastest way to get the answer.

Yes.

In fact, you could argue it isn’t important.

You can’t do it either.

It has to be a process.

It has to be a path through some belief space.

You’re always updating, whether it’s at an evolutionary scale or whether it’s during this conversation, you can’t start from scratch.

And you’re using the word belief the way here stateside, we might use the word what’s supported by evidence.

So it’s not that I believe something is true.

Often the word belief is just, well, I believe in Jesus, or Jesus is my savior, or Mohammed.

So belief is, I believe that no matter what you tell me, because that’s my belief.

And my belief is protected constitutionally on those grounds.

When you move scientifically through data and more data comes to support it, then I will ascribe confidence in the result measured by the evidence that supports it.

So it’s an evidentiary supported belief.

Yeah, I guess if we have to say belief that it’s, what is the strength of your belief?

It is measured by the strength of the evidence behind it.

Yeah, that’s how we have to say that.

So Gary, do you have any last questions before we got to land this plane?

Yeah, I do, because if I think about us as humans, we have, sadly some of us have psychotic episodes, schizophrenia, if someone has hallucinations, they have a neurological problem that’s going on inside their mind.

Yet we are told that AI can have hallucinations.

I don’t know if it’s, does AI have mental illness?

AI just learned to lie, that’s all.

You know, you’re asking a question that doesn’t know the answer and it’s just like, all right, well, how about this?

That’s what we do in school, right?

You don’t know the answer.

If you mix them up, it might be right.

Right, exactly.

What’s the answer?

Rockets?

Okay.

Yeah, I was speaking to Gary Marcus in Davos a few months ago and he was telling me he invented the world or applied the world, the word hallucination in this context.

And it became world of the year, I think, in some circles.

And I think he regrets it now because the spirit in which he was using it was technically very divorced from the way that people hallucinate.

And I think it’s a really important question that theoreticians and neuroscientists have to think about in terms of understanding false inference in a brain.

And just to pick up on Neil’s point, when we talk about beliefs, we’re talking about sub-personal, non-propositional Bayesian beliefs that you wouldn’t be able to articulate.

These are the way that the brain encodes probabilistically the causes of its sensations.

And of course, if you get that inference process wrong, you’re going to be subject to inferring things are there when they’re not, which is basically hallucinations and delusions, or inferring things are not there when they are.

And this also happens to tell us in terms of neglect syndromes, dissociative syndromes, hysterical syndromes.

These can be devastating conditions where you’ve just got the inference wrong.

So understand the mechanics of this failed inference.

I think, for example, hallucination is absolutely crucial.

It usually tracks back to what we’re talking about before in terms of the ability to select versus ignore different parts of the data.

So if you’ve lost the ability to ignore stuff, then very often you preclude an ability to make sense of it because you’re always attending to the surface structure and sensations.

Take, for example, severe autism.

You may not get past the bombardment of sensory input in all modalities, in all parts of the scene, in all parts of your sensory epithelium.

It’s all alive.

Right.

It’s all alive.

Guys, I think we’ve got to call it quits there.

Karl, this has been highly illuminating.

Yes.

Yeah, man.

That’s good stuff.

And what’s interesting is as much as you’ve accomplished thus far, we all deep down know it’s only just the beginning.

And who knows where the next year, much less five years, will take this.

It’d be interesting to check back in with you and see what you’re making in your basement.

With the Brit, Neil, it’s garage.

Oh, garage.

You guys don’t have a basement.

The basement is more the garage.

We go out there and create lots of wonderful things.

Exactly.

Exactly.

Okay, Professor Karl, thanks for joining us.

Thank you very much.

Thank you for the conversation, the chokes particularly, then, sir.

Thank you for the welcome.

You are very welcome.

The conversation.

Thanks for joining us from London.

Thank you.

Time shifted from us here stateside.

Again, we’re delighted that you could share your expertise with us in this StarTalk special edition.

Alright, Chuck, always good to have you, man.

Always a pleasure.

Alright, Gary.

Pleasure, Neil.

Thank you.

I’m Neil deGrasse Tyson.

You’re a personal astrophysicist, as always,

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron