About This Episode

Are we addicted… to revenge? Neil deGrasse Tyson, Chuck Nice, and Gary O’Reilly break down the neuroscience behind revenge-seeking, what motivates violence, and how science can help stop it with James Kimmel, Jr., lawyer, lecturer in psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, and author of The Science of Revenge.

We explore new research that frames compulsive revenge-seeking as a behavioral addiction. James opens up about his traumatic experience as a bullied teen that nearly drove him to kill. What stopped him? And how did that moment drive him to study revenge? What does the brain look like on revenge? Learn how revenge taps into pathways in the brain used for pain, pleasure, and reward. Why is revenge so pleasurable, even when it’s only imagined? Could our craving for revenge be strong enough to override our conscience?

We examine the role of the prefrontal cortex, explore why some people act out violently while others don’t. Is there a biological basis for violent crime? Could addiction frameworks and anti-craving medications be used to prevent violence before it happens? And how do social connections affect recovery from revenge addiction?

As corny as it sounds, we learn how forgiveness has an actual impact on the brain. Can imagining forgiveness really deactivate pain and addiction circuits in the brain? Why do so many people misunderstand forgiveness as something you give to others, rather than something that heals yourself? From FMRI scans to courtroom ethics, from stop-the-steal conspiracies to school shootings: is American society addicted to revenge? How do media, social networks, and politics inflame that addiction? And what happens when entire nations pursue revenge?

By the end, we return to the core question: if revenge is neurologically rewarding, how do we stop people from pursuing it? Is prevention possible? What signs can we look for before it’s too late? And could forgiveness be the ultimate tool for changing not only our brains, but our culture?

Thanks to our Patrons Daniel D., Wendi Su, Jim, Patrick Johnson, Lyleblakeo, Anabel del Val, Alex P, Harry Peters jr, Scott Syme, Katie Littman, Jarrett Rice, James, Mindy Graulich, Bart, John Dragicevich, Michelle Gerez, Renee A Chen, Sarthak Misra, Drew and Bobbi Monks, Nina Kattwinkel, Emir Tenic, Tyler Kunkel, Matt Baldwin, jscribble, Tore Aslaksen, Melina Morgan, kenneth cooke, Dale Ireen Goldstein, Christopher Arnold, Etienne moolman, Daniel S. Hall, Quillan, Jeff Whitacre, Jeremy Schmidt, Brian Reed, Frank, Micheal Trager, Irene, Robert Tillinghast, HeWhoQueries, Samantha, Laura knight lucas, Amagerikaner, Webb Peterson, Jeramiah Keele, Joe Quintanilla, kent simon, Tim Albertson, Fallon Cohen, John Terranova, Phinphan77, yocheved Devehcoy, Lasha Kanchaveli, and Nalini Martin for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTWho would have thought you can be addicted to revenge?

I mean, maybe we should have known that because Hollywood makes big money on revenge movies.

And I’m going to get them for that.

It’s been hiding in plain sight.

Coming up, The Science of Revenge on StarTalk.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk, special edition.

And as always, that means we got Gary O’Reilly.

Gary.

Hi, Neil.

How you doing, man?

I’m good.

Former soccer pro?

Allegedly.

And you’re staying in shape, you look good.

Oh, you’re such a liar.

No, most people by then, you know, they’re like, they’ve just gone to pot, you know?

Keep it sucked in, keep that sucked in.

Jack?

Hey.

All ready for another episode of special edition.

Always.

And for those who don’t know or remember, this is a spinoff of StarTalk that specializes in all the science that matter to the human condition of mind, body and soul.

Oh, yeah.

And what did you cook up today for us?

Well, Laine Unsworth and I, co-producing on special edition.

She’s our LA office.

She is in our LA office.

And we were offered the chance to investigate the science of revenge.

I’ll get you both for that.

It’s something we should talk about afterwards.

So that’s where we are today.

All of us have likely thought about revenge at one point in our lives, even if it’s nothing more than thwarting that squirrel on the bird feeder.

I really hate those little…

Anyway, moving on.

Wait, wait, wait.

Dude, this is Manhattan, New York City.

The squirrel on the bird feeder, that’s not an image to anybody here.

There are people watching this who do not live in Manhattan.

Spoiler.

Okay.

We’re here, like, at my office in Manhattan at the American Museum of Natural History.

Right.

You know, what’s funny is that you just said that to every collective Manhattanite in this city, because that is the mentality of everybody who lives in Manhattan.

I know, and I get it.

And it’s what makes it a fabulous place.

Hopefully, it’s no more than thwarting this so-called squirrel and so-called bird feeder, doesn’t exist.

But it can and it does get out of control.

How does this happen?

Why does this happen?

Researchers have begun to think of revenge as an addiction, a deadly addiction.

Yeah.

So what is your brain like on revenge?

Is it an addiction?

Big and beautiful.

Big beautiful brains all about, I am your retribution.

I am sure we will end up there.

If it is an addiction that by the way has been hiding in plain sight for most of us, then there must or should be an off ramp.

Let’s find out.

Neil, would you introduce our guest?

I would be happy to.

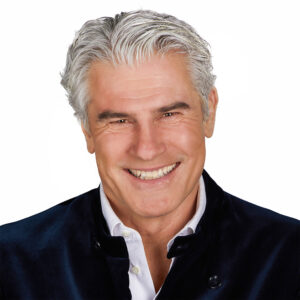

We have got James Kimmel Jr., JD., Doctor of Jurisprudence.

James, welcome to StarTalk.

Thank you very much.

I am happy and honored to be here and ready to roll.

Ready to roll.

I like that.

He’s ready.

Let’s roll him, then.

Yeah, I love it.

Wait, so.

He may not have seen the show before.

So you’ve got a JD., Doctor of Law, but you are not in any law school.

You are a lecturer in psychiatry, the Yale School of Medicine up there in New Haven.

Look at that.

And a founder of the Yale Collaborative for motive control studies.

Ooh, motive control.

How’s that for a euphemism for stop trying to kill people?

Right.

Not to be confused with motor control.

Yes, that’s a different, very different.

And you do research identifying compulsive revenge seeking.

Interesting.

As an addiction.

Oh, interesting.

Right, because it’s not just a single event in your life.

Exactly.

If you’re thinking about it all the time, you can’t get it out of your head.

Right.

And, oh, my gosh, that’s a whole other thing that got here.

You developed the first behavioral addiction model of revenge.

Interesting.

And the brain disease model of revenge addiction.

So you’re in this.

We love it.

Yeah.

And James has a book out, The Science of Revenge.

That’s why he’s on this show right now.

Yes.

That follows previous books, The Trial of Fallen Angels.

Oh, yeah.

By the way, that’s a case as a lawyer, every lawyer wants.

I am representing Lucifer, your honor, better known as God.

Yeah, but will you be the devil’s advocate?

Oh!

Booyah!

What else have we got to follow now?

Yes.

So, let’s start from scratch here.

You come to this field with a JD degree, Doctor of Jurisprudence, and how do you end up in the Yale School of Medicine with this kind of expertise?

Yeah, that’s an interesting story for sure, and maybe the better question is, how did I get to having a JD and then to the Yale School of Medicine?

I wish you had a suit.

That actually starts when I was in high school.

I was raised on a farm in central Pennsylvania.

All right.

Farmer.

Yeah, I actually wanted to be a farmer when I was a kid, and my parents moved, my brother and I out there when I was about 12, is to my great-grandfather’s farm.

And when I got there, I really wanted to befriend the farm kids who lived in the area around me, whose dads were kind of real farmers, because my dad was an insurance agent, even though we lived on this farm.

And we had, you know, we had cattle, we had black Angus cattle, we had pigs and chickens and things.

But we weren’t making our living from the land and the guys around me that I wanted to befriend.

You know, they weren’t having any of this.

I was not authentic, right?

So I was the subject of some amount of derision and I was an outsider.

So you were bullied, just say it.

We have a word for that.

I was headed there.

But you’re ahead of me and that’s absolutely correct.

I was bullied for multiple years, up until the middle of high school.

And you know, it was kind of verbal at first and then it was physical assault and kicking and punching and getting on and off the bus and going down hallways and in the locker room and stuff.

So late one night, you know, in the middle of the night, we were asleep and we awoke my family and I to the sound of a gunshot.

And we raced to the windows to look and see what was going on out there.

And I saw a pickup truck that belonged to one of the guys that had been harassing me.

So I was probably about 16, 17 years old.

And it took off down the road.

So we checked around the house to see if there was any damage and didn’t see anything.

One of my jobs every day before going to school, and one of my jobs that next morning was to go out and feed our animals, feed the cows and the pigs and also the sweet little hunting dog, a beagle named Paula.

And when I went out to her pen, I found her lying dead in a pool of blood with a bullet hole in her head.

Oh, my goodness.

Yeah.

So that was that gunshot?

That was the gunshot.

Oh, man.

I mean, that’s just out of pocket.

That’s so far beyond the pale.

Right.

That’s way beyond bullying at that point.

So what’s your reaction?

What happened?

Because that’s insane.

Yeah, it was insane.

It was pretty hard to look at that, and it was pretty hard to reconcile that with reality for a while.

But, you know, we called the state police.

That’s who patrolled the countryside.

And this was, you know, early 80s.

They weren’t very interested in it.

I mean, they felt bad, but, you know, it was a dog, and they had a lot of, I guess, more important things to do.

And so they didn’t do anything.

And, you know, my dad didn’t really do anything either, because as an insurance agent, he was selling insurance to farmers and really wasn’t going to jeopardize all of that over some kind of kid’s dispute.

And so about two weeks later, I was home alone at night.

My parents were out somewhere, and a vehicle came to a stop in front of our house.

We lived along this one lane country road, and I looked out again and saw that it was that same pickup truck, and then there was a flash and an explosion.

And they blew up our mailbox and sort of shot it into the neighboring cornfield.

And that was the moment that shot me, you know, sort of into the neighboring cornfield as well.

And we, I had been shooting guns since I was probably eight years old.

We had lots of guns living in the country.

And so I ran and I got a loaded revolver out of my dad’s nightstand and ran back through the house, jumped out, jumped in my mother’s car and took off after these guys through the middle of the night, just like, you know, shouting and cursing at the top of my lungs.

And so I caught up with them and I cornered them by a barn on one of their farms.

So you got them cornered now.

You got the revolver and wow, what happens?

Yeah.

So I had them pinned against a barn and what I see, you know, I’m in the car and their pickup truck is facing away from me.

And so I just see three or four heads lined up in the rear window.

And they slowly get out of the truck and they’re squinting back in my headlights, trying to figure out who had just chased them down their long, you know, gravel drive.

And what was clear is they were getting out as they were staring into my headlights is they were confused.

I had never really confronted them before.

I certainly had never chased them down like this.

It was my mother’s car.

Maybe they thought it was her.

One thing that was clear to me was they were unarmed and there was no way for them to know that I had a gun.

And that was it for me, you know, this was my moment.

This is why I chased them down.

And I had put up with years of abuse.

Now they had killed my dog.

Now they were blowing up things around our house.

Wait, wait, if they had just blown up your mailbox, how certain are you that they don’t have weaponry?

Well, let’s just say it this way, as they were coming out of their truck, they weren’t carrying anything.

So maybe they did in the truck, but they didn’t have it in their hands.

And so I start getting out of the car, I grab the gun, I open the door, you know, I start stepping out.

And at this last second, it would have been so easy, and it’s exactly what I was wound up to do at this point, was to take them out.

But I had this just really quick flash of insight or inspiration, and I could sort of see into my future a little bit.

And it became clear to me that if I went through with it, I would be killing the person that I knew, either real or figuratively, you know, either for real or figuratively.

And I wouldn’t be the same guy that I was before that moment in time.

I’d have to, you know, know myself as a murderer.

And that was just enough of an insight to cause me to stop.

I just knew I didn’t want to pay that price to get revenge.

And that was just enough to cause me to pull the door back shut, you know, pull myself back in the car, put the gun back down on the seat and drive back home.

So I came within seconds of committing a mass shooting.

And all over some bullying and this poor dog and all because, I guess, you know, my family were not like theirs.

And they saw that as a difference and a bridge too far for them.

Now you know what it’s like to be black.

Thank you.

There you go.

That’s a fair point.

Honestly, that’s a fair point.

You didn’t fit in and you even had the same skin color.

That’s a good point to make.

Right.

I was the same skin color as they are.

Yeah.

But I was different.

I was in their out group.

You know, I was in the out group.

Out group.

That’s all it is.

So you were imprinted here in a way that shaped your future career.

Yeah, so when I got back home and started to just calm myself down, I guess one thing that was very clear to me is that I had a gift that night.

It could have gone very differently.

And it does all the time for lots and lots of people.

Many, many, many people.

It’s two or three seconds between who we think of as the us and who we think of as the them.

And so I had a gift, but the other thing I knew is that I really still wanted revenge.

It was just increasingly clear that I didn’t want to overpay, right?

I wanted the drug.

I just didn’t want to overpay for it.

And over time, this didn’t happen that night or in those days right after, but in probably the months or year after, I sort of ran across the idea that I could go into the professional revenge business.

They call it Hitman, but…

Well, no, there’s a different profession, and that’s to become a lawyer and do it for lots of money and do it legally.

Wow.

Well, guess what?

You’re the kind of lawyer that I want on my side.

Yes, you do.

Wow.

You know, I never thought about that.

Of course, so much of what happens in the courtroom.

What’s the legal brand known as, James?

We popularize that with politically correct, polite term we use for revenge.

That’s the brand name Justice.

Oh.

Oh, yeah.

Oh, that’s a little chilling in a way, you know what I mean?

In the cold?

Yeah, yeah.

You want justice?

Well, so justice is not just in the abstract.

Justice means I’m gonna kick your ass in some way.

I’m getting my pound of flesh.

Yes.

Right.

It’s going baby, come here.

Justice is an eye for an eye.

And, you know, we do, we call it that.

So justice, in this conversation, has a whole new meaning to me, based on how this, the lead up to how that word was just expressed.

And so, okay, now that’s pretty clear how that would manifest in the courtroom, but how do you turn it into a psychiatric study?

Right.

So, well, just stick with justice for a second, because I think it’s really important to think about it this way.

But we don’t like the word revenge.

Sounds too harsh.

Nobody really wants to say, you know, I want revenge all the time.

Certainly, political leaders never want to say that.

But to say we want to bring the terrorists to justice, that sounds noble, right?

And justice has a noble meaning.

The noble meaning of justice is equity, fairness, Martin Luther King justice, right?

This is like the other side of justice, which is an eye for an eye, and we’re gonna balance the scales by, I’m gonna do to you what you did to me.

Now I have a dream that one day, I’m gonna kick your ass.

To bring equality to the landscape.

So is it DC Comics has the Justice League?

That’s correct.

That would sound really different if it was the Revenge League.

The Revenge League would not be.

There would have to be the bad guys.

Yeah, they would have to be the bad guys.

Right.

Rather than the good guys.

All right.

Well, you got the Avengers, right?

And the Avengers are actually Revengers.

That’s what an Avenger is, is somebody who goes out and punishes other people.

So they kind of cover both sides of it there, but we don’t think of Avengers in that sense as the bad guys.

We think there’s the good revenge seekers and the bad ones.

That’s not really true, but that’s how we would like to think of it.

Let’s drop into your lab.

What does the brain look like when it’s on revenge?

Is there a revenge pathway?

Are there areas that get lit up specifically?

Or is it all, well, maybe this, maybe that?

Have we found those definite areas now?

The revenge part of the brain.

There is not a revenge part of the brain, and that’s a fascinating insight.

Let me just tell you how it works inside the brain.

Please.

When you’re aggrieved, when you get a grievance, which is to say you’ve been wronged, mistreated, treated unfairly, disrespected, humiliated, shamed, any of those things, the pain of that, that grievance, the pain of that grievance, is registered in the pain network of your brain.

It’s actually like a physical, mental pain.

That makes sense.

And that’s called the anterior insula, the pain network.

And that activates when you are wronged or have a grievance of any kind.

And it also does this whether that grievance is real or imagined.

It’s imagined, right.

Which, okay, please tell me, you will tell me if I’m wrong.

But I believe that’s the same part of the brain that when someone disagrees with the deep philosophical position that you hold, that area of the brain is activated, which is why it’s very difficult to change someone’s mind when they feel like you’re attacking me for my belief.

Because they’re experiencing this same kind of physical pain, whether it’s, you know, imagined or not.

Are you asking him that or are you telling him?

I’m asking, I mean, I’m saying it, but I could be wrong.

This is just from what I’ve read.

But is that correct?

Yeah, it is correct.

And it’s registered as an attack on their ego, right?

Their identity.

And attacks on identity are very painful and threatening.

Right, okay.

So that’s step one, is you get the grievance and you get this activation in the pain network, the anterior insula.

The next step in the process is that your brain, it doesn’t like pain, right?

Our brains do not want pain.

And so they want a counterweight and they want pleasure, right?

And what the brain does next, when the pain has been inflicted in this manner, right?

That we’ve just described as a grievance, is it activates the pleasure and reward circuitry of addiction.

That is the nucleus accumbens and the dorsal stratum.

Right.

And we’ve know a lot, I mean, addiction has been studied for all these other reasons, right?

So it’s a ready-made platform on which to place this idea.

It’s the justice thing, but this time just the scales of balance.

However, normally in addiction, well, oh no, it’s, yeah, that’s right.

So is that still a dopaminergic response?

Is it still within that same?

That’s a word, dopaminergic?

It is now.

You know what?

I mean, Chuck, you’re right.

It is dopaminergic.

That is a word.

And there is that response in that pathway, in the pleasure and reward circuitry of addiction there.

So there is a dopamine release that comes from beginning to fantasize about, plan, or think about revenge seeking, and then in actually gratifying that desire or that craving to get revenge, which is what follows from the initial dopamine hit.

And so we get, intense humans get, this has been shown repeatedly in study after study, revenge seeking is highly pleasurable.

It’s right up there with drug high, it’s right up there with sex and chocolate cake and all of those fun things.

It’s all there.

My name is Inigo Montoya.

You keep my father prepared to die.

See, it feels good.

It feels good, yeah.

But you have to be eating chocolate cake and having sex while you’re doing it.

And while I’m doing that, right.

So don’t try to imitate that.

No.

That’s why I’m laughing.

James, why is it some people’s revenge is at a level of extremity that’s mind-boggling than other people’s is, by comparison, quite mild?

I mean, is it like a menu we pick and choose which revenge category we go for, or is this just chemically dominated?

Good question.

It’s not so much that, although there is different vulnerability for different people.

But for all human beings, revenge is highly pleasurable.

And so you have to move then into the last step of this, neurologically, which is the prefrontal cortex, which is your executive function and self-control circuitry.

For addiction, for people who have addiction, which about 20% of people in the population who experiment with drugs or alcohol will become addicted to it, which means 80% of the people will not.

But 20% is a big number when you’re talking about an entire nation.

Especially given the consequences of their addiction on the rest of society.

And if I’m not mistaken, it’s not heavily dependent upon, but heavily influenced by what age you start experimenting because your prefrontal cortex is not fully developed.

So the hijacking process takes place a lot easier.

If I’m correct, I’m not…

You are correct.

As a matter of fact, you could easily be guiding this conversation.

You’ve got it right at every point, Chuck.

Absolutely.

All right, I’m leaving, guys.

I got to go.

Quit while you’re ahead.

Quit while I’m on top.

No.

No, everything is correct there, and that’s where I was headed, which is that prefrontal cortex is your last defense between that initial grievance and you carrying out this powerful craving to retaliate against the person who wronged you, and here’s another twist to it, or their proxy.

So, revenge happens all the time against people, animals, objects, anything, that didn’t actually inflict to that original grievance upon you.

If you can’t get at the original person, or it would be too dangerous or too inconvenient, you will seek revenge against a proxy, or if you want to increase the overall damage, like in a mass shooter situation, there’s almost always revenge, gratification experiences, and they’re shooting people that had nothing to do with their initial grievance, but they are viewing them as a proxy, and the gratification is just as strong, whether it’s a proxy or not, and whether their grievances were real or not.

Oh my God.

So James, I’ll call it the calculating part of the brain that you exercised as a teenager, when the three guys get out the pickup truck.

What’s the breakdown when it goes completely wrong, as you’ve just described?

Is it the same prefrontal cortex?

Is this some chemical that goes on and an imbalance takes place?

Or is there another functionality that just tips someone over into that category?

Let me add nuance to that.

Are you the kind of person who behaved the way you did, and had you had different brain chemistry, you would have fired the gun.

So is there a spectrum of responses where you stay within your lane, typically throughout your life?

So we don’t know enough about it yet to be able to fully answer that, but there are studies that show, for instance, there’s a genetic component to it.

Some people do have a greater genetic vulnerability to prefrontal cortex dysfunction.

Now that doesn’t mean that you can predict that such a person would become violent.

There’s no research to support that idea.

But it does mean that you might, under the right circumstances, have greater vulnerability.

But those circumstances could be reversed in all sorts of ways.

For instance, if you were raised in a peaceful place and taught by your parents and everybody around you about acting non-violently, and you had all of your needs met, and you had a lot to live for, those factors might outweigh any genetic impairment, and you may never act violently, kind of almost no matter what somebody does to you.

Although, if they really threaten you or your family or somebody you care about, you might.

And that’s the point.

It’s a natural process.

But if there is dysfunction or hijacking, as Chuck said, of the prefrontal cortex because of the addiction, then that last wall between you and the violent act is gone and almost nothing will stop you.

And we can see, if you look at it this way, between 1 and 2 million people are in prisons today.

Let’s say a vast percentage of those are for violent crimes.

For those people, they, at the moments of their actions, did not have the resources and control in their brains necessary to stop those acts.

So we now have now a brain biological, for the first time ever, a brain biological cause of human violence.

And that leads to how we can prevent and treat it.

What is the pathway for that?

To, once you understand how to reverse engineer that situation, what pathways are available to someone who might be vulnerable to this?

Sure, so what can we do?

The first thing that this enables public health officials and mental health providers and other providers to do is use the entire addiction prevention and treatment toolkit, but train it on violence and compulsive revenge seeking.

So that’s something that was not known before, really almost exactly now.

By seeing compulsive revenge seeking as an addictive process, we can use things like, to start for prevention, public health campaigns and school programs for kids, in which we explain the dangers of compulsive revenge seeking and provide kids with resources for that.

Fantastic.

We don’t know that right now.

I mean, humanity has not known this for the last 5,000 years.

So that’s one thing we can do.

On the treatment side, all of the normal and successful treatment strategies that have been used for addiction can now be applied to people who are exhibiting signs of compulsive or addictive revenge seeking, including things like cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, counseling, maybe there’ll be rehabs at some point, 12-step programs, and then even, and kind of maybe the most exciting, anti-craving medications, like naltrexone or GLP-1 semi-glutide drugs that have been shown to, right now, in early studies, to be able to suppress cravings in other areas.

Yeah.

This is an absolute vanguard for public health because violence, unfortunately, in this country is not seen as a public health issue, and it is indeed a public health issue.

And one of the things that’s been found in the treatment of addiction is that community is very important for recovery.

So people who are in a very strong family unit, they have a very large support system, and they have people who are there to act as a firewall to recidivism, they tend to be far more successful in their recovery than people who are isolated.

So basically-

Are you running for office?

What’s that?

Are you running for office?

No, but I feel very passionately about this.

Chuck is like, damn Chuck.

This is very, very municipal, you know?

You know, I’ve done a lot of reading on this because I feel passionate about it because, you know, I hate to say this, but in the black community, this is very deleterious, to, you know, especially in-

These are forces that are destabilizing.

These are forces that destabilize our community in large cities primarily.

And if we looked at it as a public health issue and we were approaching it in a treatment way instead of a crime and punishment way, we would be far more successful.

So I just applaud everything that you’re doing.

I think it’s fricking fantastic.

I saw some show from the early 60s.

It was a crime drama show.

And they had a guy who was like a junkie.

But they all knew him, and but he finally admitted he was a junkie.

What’s happening, Roscoe?

Man, I’m just trying to make it happen, man.

But you know what they did?

You know, he’s there admitting it.

They called the cops, and the cops arrested him for his drug use.

And I looked at them and I said, whoa!

That would never happen today.

Yeah, yes, thank God.

Right, right, our attitudes are different towards someone who’s seeking help.

You don’t put them in jail.

Right, we’re getting there.

Yeah, okay.

Slowly but surely.

So, James, you know, you look at someone you couldn’t tell from the outside rapper that this person might well be a revenge seeker.

You could if you study the bumps on their skull.

All right.

Try doing that in the New York subway.

See how you get on.

The phrenologist tried, okay?

Excuse me, may I feel your cranium?

They had an idea.

Okay.

It was like total bullshit.

All right.

Where I’m going with this is, how much of the fMRI investigation is part of your research?

And has it been throwing up anything that previously was unknown?

As, you know, Neil pointed out multiple times, I am a lawyer and not a neuroscientist.

So I myself don’t do the fMRI work.

I rely on, I’ve relied for my book, The Science of Revenge on more than 60 researchers at universities around the world who have been doing this.

And they, those guys in their studies have been able to reveal these different pathways that I’ve been explaining that are activating or deactivating inside your brain.

And that is what they’re able to show.

And going back to Chuck’s point there, which is really an excellent point, a couple of things.

One is, you know, putting somebody in jail, although people need to be isolated if they’re a threat to society, they need to be out of society until they’re no longer a threat.

But you have to think about it this way.

If you try to treat somebody who has a drug addiction by putting them in a cell with piles and piles of coke and heroin, you couldn’t expect very much success by doing that.

And similarly, if we are going to put somebody in a cell for revenge addiction, their violent behavior, we are essentially doing the same thing because we’re punishing them.

We’re inflicting revenge on them, which is just activating their pain network and causing them to want to seek revenge in and out of the jail when they come out.

So we are not getting good benefits for it.

And on top of it, for every violent crime that you could categorize for the last 50 years, for instance, just in that period of time, in 100% of those cases, the criminal justice system was ineffective by definition in stopping that crime.

So we need to go beyond the criminal justice approach.

It doesn’t mean we have to throw it entirely away, but it needs to be modified a bit.

And we need to go beyond it to a public health approach, which actually goes to the biological root of the problem and start to fix it at that point.

And we have the addiction strategies to work.

And then we have one other amazing strategy to work that neuroscience has recently uncovered, which I’d be very happy to share with you guys.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, we’ll take it.

All right, before we go…

Isn’t the challenge of what you just said, the fact that society itself is susceptible to revenge addiction?

So when somebody commits a crime, we want to see them punished kind of as our own revenge response.

So it’s difficult for people to say, let’s try to help this person.

It’s the blame culture.

It’s like, no, let’s not try to help them, let’s make them pay.

Yeah, and we all feel good by doing that, right?

We feel good when the bad guy gets his final price, right?

We want that to happen.

We want that justice in the form of revenge and we want it bad all the time.

Before we get to that escalation scenario of revenge, and we will, I think our audience would like to know if any, if there is any difference at all between a psychopath and a revenge seeker.

So they could be one and the same person, psychopaths, though, are different from the rest of us, than that it’s been shown in brain studies that they have less empathy than a normal person, and may be down to zero.

But they only represent a small percentage, three or four percent of the entire human population.

So psychopaths are not the majority of people who are committing violent crimes in the country.

A lot of work has been devoted to understanding psychopaths, but it’s not really reducing crime rates because they’re not the real problem, they’re a problem, but they’re not the problem that society is most concerned about.

If we focus on the revenge seeking part and revenge addiction, we could actually get at the root of the true problem.

And many of the psychopaths, very special people, very special.

You know it, I know it.

You said something interesting earlier on in our conversation about the real and the imagined.

And I’m going to refer you to something you mention in your book, The Revenge of Science, the courtroom of the mind.

Where the jury, the prosecutor, the witnesses, the judge are all the same person.

And this scenario plays out.

Can you explain that a lot better than I just did, please?

Sure.

You did a good job.

And it can play a role in both the problem and the solution.

Let’s just talk about it in the problem side for a minute, right?

So, by courtroom of the mind, what I’m referring to there is that, and this goes all the way back even to Sigmund Freud’s observation that we kind of, all humans are hourly and daily going through our lives, doing away with the people who get in our way or who insult us.

So we’re almost always and endlessly, obsessively, putting other people on trial inside our minds, judging whether they’ve offended us or not and whether they’re guilty, deciding whether they should be punished or not.

And then at the end, we have to decide whether we’re going to carry out those punishments in the real world or not.

And with revenge addiction, the only way to gratify your craving and get that high is actually to harm somebody versus a drug addiction in which you, you know, you’re kind of only harming yourself if anyone, right?

But with revenge addiction, the entire craving process, the behavior that you seek is harming another person.

So let’s just talk about the solution side for a minute, because I think that’s where you were really going on this, Gary.

And the solution side is we talked about the addiction toolkit, and that’s available, and that’s available for public health officials.

But the more powerful, more readily available, easier to use strategy for controlling revenge cravings and eliminating the grievances in your life is called, it turns out, forgiveness.

And let me tell you what neuroscientists have found recently about forgiveness.

It’s fascinating.

So the first thing that happens when you forgive somebody is that it shuts down that very pain network, the anterior insula that I was talking about, which is the pain of your grievance area in the brain.

It turns that off completely when you forgive, which is a really important self-healing response and strategy that happens at a neurobiological level.

So can I just ask you this, then?

Maybe you can give us a better picture, because I’ve heard this.

He just described Jesus.

Forgive them, Father.

Forgive them, for they know not what they do.

Which, of course, anybody else hanging there would have been like, Yeah, I know what you’re doing.

I’m up here.

You did it.

What the hell?

Get me down.

Anyway, but can you give a picture of what forgiveness looks like in the mind of the person who’s forgiving?

Because some people have a very hard time wrapping their understanding around, what do you mean when you say, Forgive them?

The family of a child that’s just been taken, for whatever reason, for whatever scenario, finding forgiveness in those individuals?

This is in the court.

They have this in the court room all the time.

There’s the person who killed a family member, and they’re up for parole, or they could be about to be released, and they bring in the family, and this is a scenario ripe for this conversation.

Yeah, the family doesn’t come in and say, We forgive you.

The family comes in and says, This is why you should not be let out.

So what does forgiveness look like in the mind of the forgiver?

Yeah, thank you.

It’s an excellent question.

So in our society, right, we think of forgiveness and the word give, that’s part of that word, as meaning somehow a gift to the person who wronged you.

Right.

Absolutely isn’t true, and we now know that for a fact at the neurobiological level.

So forgiveness at the neuroscience level, it only benefits the victim, not the perpetrator, and you don’t even need to inform the perpetrator that you’re forgiving them to get the benefits.

The first benefit that I just mentioned was that it stops, you know, it deactivates the pain network, so you’re no longer feeling pain, but in an authentic way.

Versus when revenge seeking, you’re getting a hit of dopamine that’s short lasting, it feels good for a while, and then you’re left feeling worse but wanting more.

With forgiveness, you’re just turning the pain network off entirely.

The pain is suddenly gone from your brain, at least for moments after you’ve forgiven.

And if you continue to forgive, that pain stays away up until and through forever, because it just depends on how often you’re willing to keep forgiving until the pain never shows back up.

Do you say it does not have an important effect on the perpetrator?

It does not have, forgiveness does not have an important psychological benefit for the victim.

And what I mean by that is that I don’t want to overstate that, because I think you’re asking an important question.

I’m getting this mixed up here.

So, yeah, let me try and set that straight, because I think that’s a great question.

What I’m talking about is the benefits to the person who was victimized.

Sure, a perpetrator who hears that they’ve been forgiven, it might make them feel better for a while.

They don’t want to feel like a perpetrator forever.

So you might be giving them a benefit, but you don’t need to do that to get the benefits for yourself that you need to heal.

There’s the rub.

You don’t even have to go to them and say, I forgive you.

No, it’s not sharing.

You can actually perform the act internally and you get all the benefits of that act being performed, the same as if you went to them and said, I forgive you, but you don’t even have to give them the satisfaction of knowing that they’re forgiven.

So you can just be like, you go ahead and suffer, you piece of crap, but I forgive you.

No, but there are people who become remorseful after having committed a crime.

Surely it would boost their remorsefulness knowing that they have been forgiven.

Yes, but here’s the grub.

They’re gonna have to forgive themselves.

Wow, Chuck, it’s exactly what I was gonna say, Chuck.

You’re absolutely right.

The forgiveness that they need is self-forgiven.

Okay, Chuck, what’s your next case that you’re gonna take?

I’m just gonna, I’ll just get off of this and Chuck, you can run it because I mean, you’ve got it.

Please don’t.

No, please don’t.

Yeah, I’m shooting from the hip, so please.

Well, your hip shots are fantastic.

So what you’ve got, there’s three things that happen.

Let me go over those and then we can talk about it.

So the first thing, like I said, is forgiveness deactivates the pain network.

The second thing it does is it shuts down the pleasure and reward circuitry of addiction.

So no more are you being nagged by these intrusive revenge cravings that are driving you nuts or driving you toward committing a dangerous act.

And then the last thing that forgiveness does is it reactivates your prefrontal cortex.

It activates your self-control circuitry.

All of this happens, and it’s been shown in studies, by simply imagining that you forgave somebody.

You don’t have to talk to the wrongdoer, the perpetrator.

You don’t even have to actually forgive the person.

You can just imagine or pretend what it would feel like to forgive them, and you will experience in that moment, all three of these things all of the sudden, which usually for most people, they describe that experience as a sense of relief and kind of joy, because first of all, the pain’s gone.

That’s very relieving, and then they don’t have this craving driving them insane towards revenge seeking and revenge rumination.

They’re actually healed, and it’s a real healing.

It’s not just covering it up with some dopamine.

So, your views here by you and your colleagues at the School of Medicine, it comes across, at least on the surface, as a very novel way to think about revenge, connecting it with the understanding of addiction.

Any new novel idea in science will always have some initial pushback.

So, did you get such pushback from either a psychiatrist or a psychologist that would really rather think of it as a singular affliction that needs 300 hours of couch work?

Yes, absolutely.

So, the initial response from some people, even my colleagues at Yale, and I don’t speak for any of them or the School of Medicine.

I have to make sure that I’m clear in saying that.

You don’t have to say, we will say that.

You can say that, but I can’t say that.

And I don’t want to put any words in their mouths.

But some of my colleagues in academics in other areas, there’s been some amount of pushback, but it’s rapidly falling away, I’m glad to say.

And that’s because the evidence here, because this is really based on neuroscientists around the world now who are coming up with the same results in study after study, are starting to see that at a minimum, there does look like, first of all, that people who have a grievance and are contemplating revenge, A, are experiencing for a fact pleasure that’s been studied and shown to be so.

B, that they are experiencing some form of driven, a repetitive or appetitive, if you say it that way, craving, so that they’re being driven towards it.

And if they are unable to resist that urge, despite knowing the negative consequences, and there are almost always only negative consequences with revenge, and they’re unable to resist that, that is the definition of addiction.

But I will say most academics right now are very uncomfortable using the word addiction the way I’m willing to do it freely.

And I think that there’s a lot of stigma around the word addiction, and you may have noticed that as the language over time from, you know, the American Psychiatric Association goes from substance use, substance abuser to substance use disorder, there’s always a kind of a new gentler way of saying these things.

But I think that addiction is the quickest, fastest way that most people in the general public understand for what this is.

And I think the general population are now ahead of academics in terms of reducing the stigma of addiction, knowing that it’s not something that we need to punish people for, we need to help them to get out of.

And whether it’s a substance disorder or whether it’s gambling or sex addiction or food, whatever it is, other behavioral disorders.

Revenge is part of that category.

And I think when we call it that, then we’re able to, we are now able to bring all of these resources to bear upon it.

So I’m seeing movement.

We’ve talked about the individual, James, and I said we’d get there earlier on in the show.

What happens when revenge starts to take place on a grander scale?

What happens when it’s corporate?

What happens when, as Chuck was describing, a community’s coming together because of a need for justice or slash revenge.

What then if it becomes a nation’s revenge?

Is this a different mechanism?

That’s just what happened in 9-11, right?

In 9-11, it was like we want blood in revenge for this.

And even if no one would admit it to themselves, that’s what’s driving the whole ramp up and the rise of our military presence in the Middle East.

And there are people who can very easily take advantage of that.

Because right after 9-11, our president stood on the pile of rubble and he said, I’ll hear you, and the people who did this, they’re going to hear you soon too.

And everybody was like, yeah!

Yeah, yeah, there it is, there it is.

And basically it was like, we’re putting together the posse.

Okay, so is it just, is it like mob mentality at that level?

For sure it is, and it can be.

So in my book, I go, I actually kind of trace the course of human history in terms of human atrocities, beginning with biblical atrocities up through the Roman Empire with their revenge spectacles in the Coliseums to the Inquisition and the witch trials and all of the significant wars that have been fought.

And in all of those cases, you can find that at the beginning of those, there was a feeling of offense, there was a feeling of victimization, and that every ultimate warrior and avenger always sees themselves as a victim first, never a perpetrator, and that in every war, World War I, World War II, Vietnam, Ukraine right now, in Russia, Israel and Palestine, the Palestinians, all of these conflicts, every one of them, was the result of nationalized revenge seeking at a compulsive level.

And here in America now, and really it’s for the whole world, but it started here in America, I think, we have a particular vulnerability that we get self-inflicted, we didn’t know was coming.

Up until 20 or 30 years ago, and then from that moment all the way back in human history to the time we were apes.

Humans have never had to deal with social media and algorithms that would create a platform in which you can cause millions of people to share the same grievance at the same time with the click of a couple of keystrokes.

And the same platform that can spread that grievance like a wildfire pandemic also gives every one of those people who are now feeling aggrieved with the opportunity to gratify their revenge desires instantly by firing back retaliatory digital tweets back and forth and back and forth.

And we’re just not adapted at all for this environment.

And so now we’re at this what feels like a precipice of time in which social media is causing America to become a truly revenge-addicted nation.

And it’s a dangerous point for us.

A social fabric is imploding.

Yeah.

And it’s funny because addiction is the perfect word for it.

Just look at Hollywood and how many films that, we call them action films.

Every action film is a revenge film.

Yeah, and in fact, surely you know, the first of the John Wick films, before they numbered them, they killed his puppy.

Right.

They killed his dog.

Heard that story recently.

Yes, where do we hear that story about killing a dog?

So they killed his dog.

And you did not turn into John Wick, but there was the same motivation for thinking about how you’re gonna.

See, the thing is, what happened to James was real.

Yes.

And therefore, that was real to Keanu Reeves.

Yes, of course it was.

He’s not an actor at all.

He’s a real person.

How much of what goes on that drives a revenge is an exaggerated mental construct that would, if it happened to someone else, wouldn’t register a bleep?

All the time, right?

I mean, we see that, we see this, we actually, it even goes further than that.

Gary, it goes one step further to people, in order to get these hits of dopamine, it seems, will contrive scenarios in which they feel aggrieved, in which they feel insulted, or which they kind of create a scenario in which even other people might agree with them that they should feel insulted.

But they’ve created the circumstance from scratch in order to be able to get that new hit of dopamine.

So if you look at the Stop the Steal movement that happened after Trump lost the election, there was a manufactured grievance there.

And literally panels of judges were able to say there was nothing stolen.

Those were the results.

That was and yet it was fake news.

And yet millions of people believe that they were aggrieved and that this is a serious grievance.

Obviously, to steal an election is a big deal.

So I can understand why if that happened, people would be extremely angry about it, except for the fact that it didn’t happen.

But in their minds, it did.

And therefore, we had millions of people all at once on social media screaming that one of their most valuable and important rights had been stolen from them, and they needed to do something about it.

If you look at, I cover, I will have a whole chapter on Hitler, Stalin and Mao.

All three of them were revenge addicts extraordinaire.

And I kind of recount from their childhoods forward, where that started to become manifest.

And what they were able to do in their nations was to be able to, in fact, their countrymen, all with the same grievances over and over again, and then give them an outlet for seeking revenge that always empowered themselves.

But they used revenge addiction at a national scale to do all of that work.

So the dopamine guarantees an exaggeration of whatever the original cause or justifiable response would have been.

I’m not sure if we know that, that the dopamine gains that, but it does cause people to seek it out and manipulate reality even in order to get it.

And that’s to Neil’s statement, that’s the exaggeration.

And the reason why you need that is you don’t even know it, but you are seeking this pleasurable response that your brain gives you.

So even when you’re presented with all the evidence in the world that says the election was not stolen, you can’t accept that because you need to be aggrieved in order to get your little fix.

And so you discount that and then you go along with, you know, stop the steal.

That’s right.

It’s diabolical.

It is.

And that happened in Germany with the stab in the back.

I mean, these are these little phrases that do the aggrieving and give you the opportunity, or there.

So the stab in the back myth was what Hitler stated to the German people over and over again, for them to feel aggrieved that, you know, people in their society, Jews, other politicians, had stabbed Germany and German soldiers in the back by agreeing to the armistice and the Treaty of Versailles.

Right.

Oh, man.

At the end of the first war.

You’ve set up a number of programs within the prison system here in the US to help inmates.

Is revenge actually curable?

Revenge isn’t curable because revenge itself is believed to be by evolutionary psychologists to be a evolved adaptive strategy that humans began to need, starting maybe as early as the Ice Age.

And the theory, the dominant theory right now, is that humans evolved a revenge urge and therefore pleasurable experience of revenge seeking at that time.

Because they needed it in order to be able to live in groups and societies.

So humans were coming out of the caves and they were starting to live in community.

Well, why does that mean revenge?

Yeah, so to live in community, you need the people in your community to all agree upon and comply with social norms of that society.

So that might include things like, hey, don’t go and take my wife.

Or, hey, don’t come and take my stash of food.

These are all the problems that arise out of groups being together.

Coming together, yeah.

And you need some way to keep that in check.

Is a force to contain behavior that would fall out of the norms necessary to sustain the colony?

That’s correct.

That’s exactly right.

So basically, there was a caveman who was just like, we’re gonna go down to the quarry and we’re gonna get rocks.

All right, before we wrap, I have one final question for you, James.

How likely is science going to be able to not just prevent violent acts, but get to a point where we’re able to predict them in advance?

Dude, that was a movie.

Yes, that was the movie with the precox.

With the precox.

What was that movie?

The Minority Report.

Yes!

Tom Cruise.

Yes, that’s when I had a man crush on Tom Cruise.

But he’s old now, so I gave him up.

No.

You’re just as old as he was back in the day, but no, fine.

Is the fact going to follow the fiction?

Okay.

Well, right now, we can’t predict who would become addicted to anything, like drugs or alcohol either.

So I don’t see anything, at least in my area of research, that would lead us to the point easily where we could predict somebody who was likely to commit an act of violence or a type of person.

But there are signs that we can use to speed that along in this sense.

What I identify, and I’m hoping public health officials will pick up on this, is the idea of revenge attacks being similar to a heart attack, which is in a medical emergency.

So, with a revenge attack, right, you’ve got somebody who is now heading into the throes of serious revenge seeking.

Maybe they’ve already moved towards planning, they’ve identified a target, they have potential access to weapons or are amassing weapons.

When we start to see these types of signs, and they’re always talking about a grievance or grievances, and they’re always ruminating on this and obsessed with it, and they’re letting it interfere with their lives.

Those are signs that we can start to think about.

And your legal profession holds that as the most severe form, if murder is committed, the most severe form of homicides, premeditated murder.

Ah, yes.

That’s, you know, the planning and the execution.

This is where family comes in.

And you’re coming as an attorney.

You’re unraveling that into something that’s bio-neurological.

That’s right.

Right.

Yeah.

We now know what’s happening inside the brain of that same person, which we didn’t know before.

What’s happening inside the brain doesn’t exculpate them in any way.

This isn’t about creating legal defenses.

I mean, whatever your actions are.

Well, you guys came up with a Twinkie defense.

So don’t tell me there’s not a defense in this.

Somebody will try, but I am not supportive of that idea.

Somebody who commits a crime while addicted is still guilty for the crime.

It’s not recognized as a legal defense.

And I don’t think that’s ever going to be.

But it can be recognized as a health issue.

And if we’re trained and we know ourselves, if that’s happening to us or somebody that we see, we could call 9-1-1 or 9-8-8 and start getting that person medical assistance like we would for somebody in the throes of a heart attack before there’s a death or an act of violence.

This is family members, this is community looking out for each other if they see something.

Knowing the signs.

Yeah, being aware because the tragedy is however many steps away.

Yeah, the kids shoot up to school and only after that they say, oh, look what we found in this room.

Yeah, that’s a little too late.

We see the signs.

The signs were there all the time, that’s what they say.

The signs were there all along.

Dude, give us a happy thought now, please, as we wind out the show.

The fantastic news here, and it really is fantastic, is that simply imagine forgiveness when you’re in pain.

Feel that pain go away.

That’s all you need to do to get on the road to healing yourself and avoiding doing something horrific like committing a violent crime.

It’s really that powerful.

We should be thinking about it as scientific support for the ancient forgiveness teachings of people like Jesus and the Buddha and Lao Tzu.

Forgiveness isn’t anything other than a superpower for humans.

It really is a human superpower for healing yourself.

And you ought to take advantage of it as often as you can because it’s free.

You don’t need a doctor.

You don’t need a prescription.

Okay.

Very good.

And the book, I so look forward to that being a bestseller.

Any book that can make society safer and more pleasing place to live needs to be up there.

Absolutely.

The Science of Revenge.

The Science.

And the subtitle of this book, The Science of Revenge is understanding the world’s deadliest addiction and how to overcome it.

Nice.

Right on.

Right up to the national level as you brought up there.

Well, I’d like to land this plane with the little cosmic perspective I might offer our audience.

With this discussion of addiction being an ailment that can be applied to revenge, oh my gosh.

I’m reminded of how many things used to be just blameworthy of people’s conduct that we came to understand and have sensitivity to and realize that it is a problem of society and of our neurochemistry.

And when you look at it that way, we all are accountable for the behavior of the one.

And that’s a different world that I’d like to think we’re evolving towards.

And that’s a cosmic perspective.

So, Sir James, thank you.

Thank you, all three of you.

What a great conversation and appreciate it.

And this will come out, I mean, just because of the time it takes to edit this, right around when your book comes out so your publicist was right on time with this.

And best of luck, you need a little bit of luck too when you’re selling books.

Let’s get Jimmy Kimmel to endorse it.

That’s what I need, that’s really what I need.

No, you just need us.

We’re the ones who’ll put you on the list.

The fact that you guys are here is a big deal.

So I’m really honored to be part of your show and to meet all of you.

And just, you’re all, I mean, not only are you hysterical, but extremely bright, and that’s a rare combination right there.

Excellent, and let this be, live uniquely in your portfolio of interviews that you do for the book.

It shall do.

So that’s all the time we have.

That’s all the time we needed to really figure that one out.

Whoa, this has been another episode of StarTalk Special Edition.

Gary, Chuck, always good to have you.

Always a pleasure.

All right, until next time, I bid you to keep looking up.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron