What is the relationship between art, science and creativity? Join us as Neil Tyson explores the nature of creativity with musician, author and former Talking Heads frontman David Byrne. The two discuss whether creativity is hindered or enhanced by restraints, how music and architecture are related, whether machines can be creative, and why studying art makes for better scientists and mathematicians. In studio, Neil is joined by the multi-talented Dr. Mónica López-González, Ph.D., who is not only a cognitive neuroscientist but also a concert pianist, photographer, author and more. Plus, you’ll hear from Professor David Cope, who taught a computer to compose music, and listen to an original piece which it composed in the style of Vivaldi. Maeve Higgins co-hosts, and Bill Nye weighs in on the value of creativity to human survival.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

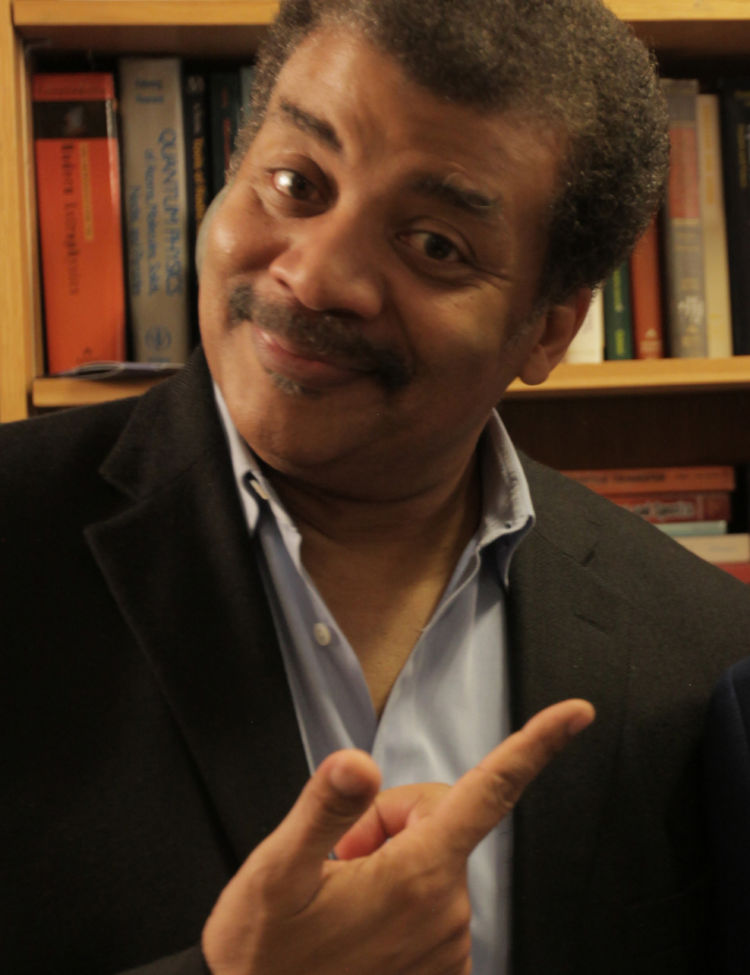

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Welcome to the hall of the universe. I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, and you are watching StarTalk, where tonight we're...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Welcome to the hall of the universe.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, and you are watching StarTalk, where tonight we're featuring my interview with David Byrne, who's the creator and songwriter for Talking Heads.

He came by, I nabbed him, put him in my office, and we talked about the creativity involved in science versus art, and whether one day intelligent machines will be as creative as we.

So let's do this.

I've got with me as a co-host, Maeve Higgins.

Maeve, welcome back to Star Talk.

Yeah.

And we have with us a special guest, an academic guest who's also a talented artist, and we have Mónica López-González.

Welcome, Mónica.

She's on the visiting faculty at Johns Hopkins University in Cognitive Neuroscience.

Very cool.

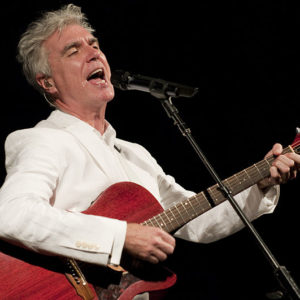

So we're featuring my interview with David Byrne, a hugely creative person, and he was the key, he was like the front man of the Talking Heads.

And they sort of pioneered the video music revolution back in the early 80s.

And from my notes on him, he, Talking Heads stopped in like 1991, but he's been continually busy since then.

And he's been a deep thinker about music, about art, about creativity, about philosophy.

And our conversations basically went everywhere.

We had to, I had to keep like reining it in.

It's funny that your conversations went everywhere with him because like when that happens with me and my friends, it's just more like, do you like guacamole spicy or medium?

But I know that's not what you mean with David Byrne.

But you would count that as a conversation going everywhere.

Yeah, I'd be like, ooh, let me think.

Whoa, whoa, I can't decide.

You really challenged me intellectually.

So I can imagine you two, sheepers.

So what I wanted to know, which I ask really all of my guests when they first walk into my office, especially if they're drawn from some very visible swath of pop culture, I just like knowing what kind of math background did they have?

Did they have a science teacher that they liked?

Is there some story they could share with us about that experience?

And did that experience somehow influence their career path?

And so let's check it out.

There was a math teacher who taught math using Alice in Wonderland, which was a lot of symbolic logic.

And Charles Dawson was himself a mathematician.

Yes, and that was his specialty, symbolic logic.

If this says this, then this means this, but then does that mean that?

Not necessarily.

Not necessarily, yes.

Well, that's quite creative.

I love that.

How many people in this universe get to say, I had this wonderful math teacher.

This is rare.

Well, it is rare, and it shouldn't be rare.

It shouldn't be rare.

It shouldn't be rare.

But I'm telling you it was the first time I ever heard that.

It's fascinating stuff.

The next year I had, sorry, a terrible math teacher, and my grades went straight down.

And it just shows how much a teacher means.

Maybe if I was somebody else, I could have just pushed through there and go, come on, I'm interested in it.

But when I finished high school, I think it was a coin flip.

I was either going to go to science, engineering, all that, or an art school.

And it was kind of a coin flip.

And I went and looked, and then I thought, art school looks more fun, at least in the first part of the ramp.

And it looked like the science and engineering does a lot of hard work, and then you get to actually exercise your imagination.

To me, there seemed to be no difference in the kind of creativity and imagination that goes into either of those areas.

I thought, they're equivalent.

So let me ask you, Mónica, would you agree that creativity in the sciences, math and science, versus the arts, is equivalent?

Because that's a big position he's taking here.

And you study the stuff.

Oh yeah, no, I don't make a difference between the two.

So you agree?

Completely.

I was so interested in what he was saying about the Alice in Wonderland, like the symbolism in Alice in Wonderland.

Yeah, so Lewis Carroll, he's a mathematician.

And Alice's Adventures in Wonderland have been studied by mathematicians.

And just the phrasings, the bending of time that's within it, it's all in there.

And in fact, the late Martin Gardner wrote a book called The Annotated Alice, where every passage within Alice's Adventures in Wonderland has an explanatory note about how it relates to math and science.

And so, oh, you're making a face.

Like, would that destroy the story for you?

No, no.

Why would that enhance the story for you?

I was just thinking about Rap Genius, that website where you can go and see what they're talking about.

Oh, okay, the translation of it.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Because when I was reading Alice in Wonderland and the tea party was for time, but I didn't understand that that's why they were all stuck there.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Because time was gone missing.

So you think there should be a website for classic literature that gives translations of it?

Totally.

Okay.

So, Mónica, what's going on in the brain of a creative person when they're being creative?

Well, so what's interesting is that creativity, I mean, is a whole brain process.

Does that mean you use all parts of your brain?

Yeah, of course.

So, for example, at least in music studies and looking at musicians that are improvising, it's been shown that they have heightened activation in pre-motor areas, motor areas of the brain, so that they're obviously getting prepared to coordinate an action.

Wait, wait, does that mean if you're highly trained and rehearsed at it, you don't trigger the motor parts of the brain as heavily because it's sort of...

It's rote.

It's rote.

It's rote memorization almost.

Okay, so if you're going to up with something on the spot, what you're saying is there's more activity?

Heightened activation, yes.

Heightened is the right term.

It's all about terminology, right?

I'll be fluent with you.

I'm hanging with you.

And so another really interesting finding is deactivation of prefrontal cortex, and prefrontal cortex is the seat of executive functioning, so being aware, moral thought, judgment, everything that makes us human.

So when you say executive, you mean high level...

High level thinking.

That's what you mean by executive.

We're not talking about the business deal.

Right, that's what I'm saying.

Yeah.

So that's kind of high level functioning too.

And so there's what's called deactivation, so perhaps you have to turn off awareness to be in the zone, to be able to improv.

Well, there's an interesting fact that we've seen, or at least a hypothesis, let me put it at that level, where if you have unbridled space to be creative, it might actually interfere with your ability to be creative.

And David Byrne actually wrote a book, and the title was With How Music Works.

But in there he explores constraints on creativity and how that can actually stimulate creativity itself.

Let's see what he says.

The pleasure that we get through our senses, we tend to think of it as being connected to our body and our tongues and our eyes and stuff.

Physiologically.

Yes.

But all the work is going on in our brains.

I mean, the eyes are just little stalks out there, and the processing tells you what you're actually seeing and what you're not seeing, what you're interested in and what you're not interested in, and that the pleasure is in making those things connect.

We tend to intellectually think or separate, well, maybe scientists don't, but kind of the common...

Conventional wisdom is that the senses are out here and that our minds are in a different place, but they're not.

They're in the same place.

The closest I came to that, I was at the Banshell in Boston, was it the Boston Commons?

I forgot what they call it.

It's on the Charles River there.

And it was Arthur Fiedler on July 4th, playing, conducting, of course, the Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture, and they had the Howitzer Cannons over on the side, and there were fireworks.

And so there I was, listening to this bombastic music, feeling the cannons go off, watching fireworks.

It was a sensory overload.

I mean, a delightful sensory overload.

Rarely do you get to have all those senses stimulated simultaneously and in harmony.

Music is affected by all the contexts that surround it.

They were affected by the kind of acoustics of where it's performed.

They're affected by the technology that records the music or the technology from the people that make it, the instruments and all the other stuff.

They're affected by the financial stuff, how you get paid or not paid or how you make a living as a musician.

Affected by how you...

We, the consumers of music, never think about that.

Yeah, yeah, we just think it just comes.

It just comes.

It just pours out.

It comes out of you.

It's like water coming out of a tap.

Yeah.

But it's...

There's all these factors that affect it.

And it's sometimes unconscious.

People know that if this is what can be reasonably done in this space, in this room, for this amount of money, they'll start to kind of self-edit and restrict themselves to thinking within those parameters, which is not a bad thing at all.

I was going to say exactly that.

In engineering, the last thing an engineer wants is, invent this thing for me, and you have unlimited money and unlimited constraints.

No, that's not where you extract the creativity of an engineer.

You get the creativity by saying, okay, here are the parameters.

It's got to do this under these conditions, under this temperature, and it's got to fit in this box and run on this much power.

Go.

Then, oh my gosh, this is a playground.

You're the engineer.

Yes, and the same is true.

It's certainly true for me.

So, the constraints are not really constraints.

They are...

No, they're liberating.

Liberating.

They allow you to kind of...

Okay, the clearer I know what is the box that I need to work within, the happier I am.

Then I can...

It eliminates that infinite number of choices and whatever.

I'm just going to be lost in there.

You've reduced the variables.

Yeah.

Mathematically speaking, if you have too many variables, you can't constrain the system.

Yeah.

So you've got to tighten out...

You've got to clamp down on some of the variables.

Leave a few that you can then manipulate.

And then get the thing to work.

Yeah.

Art and science have that in common.

So the two of you are both creative people in your own ways.

Do you agree?

We kind of agreed...

I agreed with David that constraints are actually a good thing, not a bad thing.

And in a way, they're liberating.

Would you agree with that?

Yeah, I think so.

Like, definitely how much money you have to do something or like how much time you have to do something totally helps.

Like if you're just like, I'm going to sit down, I'm going to write a book about whatever, you'll just be there.

Well, when we come back on StarTalk, we will pick up my interview with David Byrne and we'll talk about experimentation.

Of course, we do that in science.

But apparently it's also a fundamental part of part when we return.

We're sitting underneath the Hayden Sphere, containing the Hayden Planetarium, of which I serve as director.

So we're featuring my interview with David Byrne, and we've got you, Maeve Higgins, and Mónica López-González.

And the band Talking Heads, I think it dissolved in 1991, and that's many years ago.

So what's he been up to?

Well, recently, he did something he had never done before, and here it is.

This year, I'm doing a project where I'm bringing together ten high school and slightly older color guard teams.

There's the kids with the flags and the sabers and the rifles and all these things that they do, with ten kind of live musicians, kind of groups of live musicians who have written music, especially for these teams, and see what happens.

There was a little bit of tightrope walking there and trying to figure out, okay, how much can I play around and experiment and still find a way for it to kind of pay for itself and not just be like an indulgence.

But I've kind of navigated that throughout my life.

Part of the interest is in finding these kind of pockets of creativity that are going on.

I mean, the musicians, the musicians I know, I admire them.

I love a lot of what they're doing.

This other stuff is something that I don't know that I kind of stumbled on and I go, look, there's all this kind of creativity.

It's outside of my world.

New York has never heard of it.

It's going on out in all these other little towns and they're passionate, they're dedicated to what they're doing and they're creating this crazy stuff.

Somebody needs to bring that up and show some love and appreciation for what people are doing outside of kind of the official cultural channels.

Is that anything different philosophically or spiritually from George Harrison learning about the sitar at a time when no one really knew what the sitar was in the West?

Is that the same thing as Paul Simon going to South Africa, bringing some of those sounds in?

They're going on and serving their niches, but maybe there's a place to give them a new birth or a different kind of flavor.

Yeah, there's a similarity, yes.

Because everybody's got music.

Yes.

Everybody's.

And some people are, what they're doing is sometimes so beautiful and sophisticated, and you can learn so much from it.

This other stuff, though, is more homegrown.

It's more like, oh, there's something in my own backyard that I didn't know was there.

I'd never heard of this concept before.

Homegrown creativity may be drawn from the firmament in your locale versus something more mainstream.

So, Mónica, can you address that?

Sources of creativity is what this comes down to.

Sure, yeah.

And I liked how he said pockets, finding pockets of creativity within that, because I think what he's saying is that if you stay in your one medium or discipline, it makes you remain stagnant in it.

And when you go and look at other mediums or other disciplines, you end up having a larger vocabulary of information.

So, you actually make bigger the constraints you can now deal with.

And so, you can play with them at this point.

And so, when you create something different that maybe somebody already knows about, it's still different because now you add your personal experience to it, as much as you bring in whatever it could.

You've incremented it along some direction.

Exactly.

That would not have happened otherwise.

Yeah, that's the novelty of it.

Yeah.

And that sounds incredible that he is like, I don't know what the color guard is, but he said it's children with sabers.

And then he said, like, New York doesn't know about it, but I think I've seen kids with sabers here.

It's on the train.

So, yeah, that sounds incredible.

And that he would add music to that, and then all of our heads would explode.

It sounds great.

So, but it also speaks to the value and need for experimentation, which is something we do in the science lab, of course.

It's deeply associated with that activity.

So, Mónica, tell me about it.

But so is art.

Tell me about it.

Art is experimentation.

Tell me about it.

I mean, both art and science are about, you have a question, right?

You have variables that you start manipulating and testing, and then you have a product, an outcome.

I just described the scientific method as much as the artistic method.

And so I think, I mean, they're identical, really.

It's just the tools that you use.

That's what's different.

Well, here's an interesting difference, Maeve.

When you experiment, you can bomb.

Yes.

Well, I've never personally bombed.

But I've definitely seen guys in particular who can't do it.

And yeah, it's brutal.

And it doesn't necessarily mean that it's like you went wrong or like you did it bad, but it's just not the results you were hoping for.

In our case, that's a laugh.

And the opposite of a laugh is like silence or like something being thrown at you.

And that's a tough one.

Yeah.

But can't we also note here that in science, I can perform an experiment and if it works, it works.

And it's not subject to anyone's interpretation or anybody's emotional state.

Whereas you as artists, you are, if you're a performing artist, as both of you are, you have to feed a mind state.

And maybe it feeds this mind state and not another one.

Maybe it feeds Tuesday night and not Friday night.

So that's kind of different compared to my experiment in the lab.

The reaction part of it.

If I get a different result on Friday than I did Tuesday, I messed up in some really bad way.

Well, because science is about reproducibility.

You have to tell me that Fridays has an effect on my experiment.

And we invented the name, the days of the week, right?

The days of the week have no astronomical relevance at all.

Yes.

So I think then the one difference between art and science is that science is about reproducibility.

Yes.

But art is all about creating something new every time.

If you reproduce it, it's not art in the sense of novelty.

I would dare to say.

I like that.

Well, when StarTalk comes back, we will pick up my interview with David Byrne and we will explore the relationship between music and architecture on StarTalk.

We've been featuring my interview with David Byrne, and in this next segment, I want to get straight to it, because it's a highly innovative idea regarding music and architecture.

Let's just see where he takes us on this topic.

When there's certain size rooms that sound a certain way, the natural kind of artistic evolution is that the music that gets performed in them should sound the best in that room.

The easiest one, maybe, to imagine is, say, a Gothic cathedral.

The music that's generally heard in there is very kind of long notes, not a lot of complicated harmonies or chord changes, nothing very quick and rhythmic.

It seems to me that would get lost in the resonance in the echoes of the chamber.

And the music that works best in that is the music that was written to be played in those spaces, allows for those long echoes, and that long echoes actually enhance the music and make it sound more spiritual and awe-inspiring and, yeah, of the cosmos, whatever.

But you can then imagine, say, as people sometimes mistakenly do, and say, let's have this, we're gonna have this percussion ensemble play in the cathedral because what a beautiful venue.

And you realize what a sonic and cultural disaster that would be too.

It just becomes this cacophony of noise.

And you just go, God bless, but this is the wrong kind of music for this room.

So he developed this concept in his book.

What was it?

How music works.

In there, he elaborates on how the evolution of music has co-moved with the evolution of the spaces in which it has been performed.

And he gave the opposite example, I mean, the inverse example, where you have a small club and do you bring in monks to sing Gregorian chants in a small club?

No, the music is different.

And if the music doesn't sound good in that space, it's not invited back to play in that space.

So there's this filtering that puts music in their proper venues.

And I was intrigued by this, first by the acoustics of it, the fact that he thought about it.

And I was just wondering, Maeve, you have a certain joke.

Is it funny in every size venue?

Are you venue-influenced?

Totally.

Yeah, totally.

Comedy works best in...

I wonder if one day I hear the word partially come out of your mouth.

Totally.

Comedy works best in small venues, I feel like, the more intimate.

I don't know if it's to do with sonically or not, or if it's to do with actually it's a conversation, so you want to be close to them, and you want to let them breathe, and you say something, and then laugh, you know.

But I feel like I would say that because...

So it's more of an approximation of a one-on-one thing.

Right, like a conversation.

But then when comics get really successful, they book arenas.

And then people often say it's a disappointing experience, because arenas are supposed to be like, for what, like sport rock music, sports, you know, so you lose something.

But there's another issue regarding how we receive our music.

And there was a day when it was only live, because there were no recordings.

Now there are recordings.

Or then there was radio.

And then there were recordings.

And how do you, in terms of what's portable and you take around with you, we take around the recordings.

And sound quality is an interesting, it's not always the same.

And does it influence your appreciation?

These are interesting questions that I asked.

And I wanted to know what David Byrne thought about it.

Let's check it out.

When I was junior high, whatever, 12, 13 years old, something like that, and I first started listening to music on the radio, it was on a little transistor radio, about that size that you would kind of sneak into bed and quietly listen to it under your pillow.

The speaker was that big.

It was tinny.

It was tinny.

The sound on contemporary smartphones is probably better than what was on those things.

But at the same time, it's still kind of very limited.

And I realized the music that I was hearing out of this crappy little thing changed my life and changed, and made me realize, well, you hear this really crappy thing, but there's enough information there for you to know there's a world out there.

There's people doing things that are...

It's a portal.

It's a portal, and you go, there's people doing things that I didn't know about, and it's speaking directly to me.

That little thing with the crappy sound does all that.

So I thought, okay, fidelity and the kind of beautiful sound that can be produced is not...

It's wonderful, but you can't demand it.

The crappy sound can have a huge effect as well.

So, Mónica, what does he mean by fidelity?

Good sound quality.

I mean, the information is all the raw information that you have.

You're hearing every bit of it, every piece of it.

So fidelity is the reproduced music versus the music that was played, because you might lose something going from one to the other.

Okay, so he's arguing against this...

That you don't need it, right?

Well, not to be influenced by it.

I have to agree with that.

Would you agree?

Again, I think it depends on context.

I mean, because he said this little crappy thing, but because I was in my room listening...

I mean, it has emotional content, and I think it's a cross between...

He's under his pillow in his bed.

Yeah, I mean, he's having a fun time, and I think that's affecting his experience with that.

And also, there's the question of just art in general.

If it's meant to have an expressive quality, you'll get it no matter how you're hearing it.

Well, when StarTalk returns, we will go into our Cosmic Queries mode, and we will field questions from our fan base asking about the physics of sound when we return.

Thank We're back on StarTalk, and I've got Maeve Higgins, I've got Mónica López-González, and as you know, we've been featuring my interview with David Byrne, but right now, we're going to take a break from that, and we're going to go to Cosmic Queries.

Cosmic Queries.

So Maeve, you have collected questions from the StarTalk fan base.

I've not seen the questions before.

The point here is not to stump me.

I mean, if I don't have the answer, I'll just say, I don't have the answer.

But it's more fun if I hear it now for the first time, which is what you're about to do.

It's the physics of sound.

This is from Derek Azuik Chia from Anchorage.

How would voices and sounds in general change from world to world?

For instance, do sounds change in pitch and frequency on Mars or Titan?

And if so, in what ways?

Yeah, that's a great question.

So the frequency with which your vocal cords vibrate depends on the density of the air in which they're embedded.

And so if you breathe helium, which is very low density air, the frequency of your vocal cords rises and you sound like Mickey Mouse.

And so what about Mars?

So there are other places where if the air is denser, then you'll sound like this.

You can get a person with a high-pitched voice and they'll sound like the munchkins in The Wizard of Oz.

Like someone had really deep voices, deep gravelly voices.

So you have that kind of, so yes, yes.

And we don't think much about that because normally we're breathing the air we provide ourselves.

You're not gonna say, yeah, let's just breathe Martian air.

No, because you're not gonna be worried about what your voice sounds like while you're gasping for oxygen.

Yeah.

So, so.

It's just sexy to you.

So it's just not practical to test.

So yes, you will sound completely different on different planets.

It's a great question.

All right, another question.

Michael Bruce from Mountain View in California.

Is it a myth that opera singers can shatter glass by singing high enough?

I've not seen it done, but I don't see why it wouldn't be possible.

Because there's certain frequencies that are called resonant frequencies in other objects.

And have you ever done this?

Go up to a, maybe not.

I've done it.

You go up to a tree that's way thicker than anything you would think of toppling.

Okay?

And then you just start pushing it, right?

If there is a rhythm with which you can push a tree, that pumps the tree in exactly the motion that you would originally set it to do.

It's the same thing as pumping when you're on a swing.

It's how you can just put yourself into motion without touching anything.

You sort of swing your legs right at the right moment that will add to that motion.

Then you tuck your legs back right at the right moment.

So you can do this to a tree, and you will hit a resonant frequency of the tree.

And if you do this enough, you can actually snap a tree in half.

And so...

Yeah, oh yeah, I do it all the time.

It's fun.

No, no, no, I don't do it to the point where I kill the tree, but it's fun to just watch this pumping.

It's literally, in physics we call it pumping.

You're pumping a system in a resonant frequency of the system itself.

The system wants to sway at that rate.

Now, if you pump it in exactly that way, all that energy stays there.

And then the tree starts blowing it, it's waving in the breeze, and it's a sense of power over nature.

I did this, I still do it today.

So somebody's vocal cord, somebody's voice.

Right, so you get an object that has a resonant frequency.

The glass?

Yes, that a human voice can reach at a high enough volume, and then it'll start vibrating, okay?

If it's at the resonant frequency, and if you can vibrate it with enough energy, at that frequency, the glass is not going to be able to stay with you, and you'll just crack it.

So that's, so that, so, yes.

It's possible.

Oh, yeah.

Yeah.

We need to demo it.

So we've been discussing sort of creativity, how it manifests in art and in science, and I had an hypothesis that creativity in science is fundamentally different from creativity in art.

Now you'd probably disagree, as did David Byrne, but why don't you hear me propose it to him?

You'll hear his reply, and I desperately am interested in how you react.

Let's check it out.

Einstein discovers relativity, and he's a brilliant genius and all the like, but none of us would ever say that without him, relativity would never be discovered.

Somebody would discover it later, or some combination of people, it would come out, it would rise up.

Whereas if Beethoven never composed his Ninth Symphony, nobody is, ever.

So the work of art is singular in space and in time, whereas the work of the scientist, it may be a little ahead of its time, but its time will always come.

Gee, I would argue that nobody's gonna write Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, but somebody's gonna write something that partakes of a lot of the same elements.

It may not be as good, but the Zeitgeist or whatever, they're inspired by what is available at that moment, the instruments, the concert halls, what kind of orchestra you can put together, what's available, who's commissioning, how much the commissioner will put up with as far as innovation.

All those factors, I think, will allow something to emerge that is maybe not as good, certainly not the same, but in the same universe as opposed to, it's not gonna, what I'm saying is, it's not gonna sound like Bach.

It's gonna sound more closer to Beethoven.

This is just me saying, and that at any moment, I would think, and I could be completely wrong, that when there's a Beethoven, there are lesser Beethovens kind of orbiting around, sometimes much lesser, and that we will never ever care about.

Some have chaotic orbits.

Yeah, yeah, whatever.

And that the Zeitgeist says that, yeah, I'm really suspicious of the kind of singularity idea that there's the great man theory of history or whatever that might be, or the arts, where I do feel like there are certain people where lots of the factors come into focus, and that person just kind of-

The benefit of buoyant forces.

Yes.

They kind of buoy to the top and shoot up like a fountain.

He's thinking there's a universe in which Beethoven creates, and others are in that universe, so we don't have to think about whether someone will create that exact symphony.

And I was just saying, people praise that symphony, and people praise relativity.

Without that symphony, there is no symphony for people to praise.

But without relativity of Einstein, somebody would have come up with it later.

That's all I was trying to say there.

So, Mónica.

I think what science is looking for are the sort of absolutes, ideas, concepts that are independent of us.

Yes, independent of our own creativity.

While the Beethoven example or the Bach, whoever it is, is so-

Exists only within us.

Yeah, it's totally personal, but it's also dependent on society and culture, your environment, context again.

Yeah.

So, I mean, there's a Bach, and there can only be a Bach, but that doesn't mean that other individuals who are around at this time would be influenced by similar factors.

But because each person is unique with different experiences, they will use all of that in different ways.

So when StarTalk returns, we're gonna talk about artificial intelligence as a source of creativity, possibly supplanting the greatest creativity we've ever expressed as humans when we return.

StarTalk, one of the live audience in the Dorothy and Lewis Coleman Hall of the Universe at the American Museum of Natural History.

This is my day job right here.

This is your, yeah, you come down here, get your coffee.

I chill with the cosmos, this is what I do.

We've been featuring my interview with David Byrne, highly creative guy, founder and songwriter for Talking Heads.

And up till now, we've been talking about creativity and how that can be a manifestation of your culture and how different things within your culture can produce one kind of creativity versus another.

And at one point, given our state of technology, at some point you gotta ask the question, is creativity purely a human thing or will machines ever take that place?

Can you have an artificially intelligent computer that not only feels but expresses itself?

That's a question that I think needs answering.

Now, there are people out there who are working on this.

You could just Google it.

I got Professor David Cope from UC Santa Cruz, okay?

He's written a computer program that can compose original music.

And I'm thinking, should you be scared of this if you write music?

No.

I like your indignance with which you answered my question.

Well, we've got Professor David Cope on video right now, live from UC Santa Cruz.

Can you bring him on for me?

Welcome to StarTalk.

Honored to be here.

So, Professor, you've written a computer program that creates music, that has a creative...

What the hell does your program do?

That's what I should be asking you.

Well, I've written more than one program, but the first program that brought a lot of notoriety was written in about 1980, and it's a program called Experiments in Musical Intelligence, and it fundamentally is a program that takes the database of music by typically a classical composer, because they're dead and because they can't sue me for imitating their style.

It takes a large body of that music and analyzes that music and fundamentally tries to create a new composition in the style of that music, but essentially not replicating any of the pieces that are in the database.

So I'm told you actually have a clip you can share with us?

Yes, I do.

It's a part of one of the movements of a work not written by Vivaldi, but hopefully in Vivaldi's style, called The Zodiac.

Okay, let's do it.

So that's crazy.

That's like, I could listen to that.

I hope so.

I could listen to that all day.

You too?

Yeah, yeah.

And since I'm not like a music historian, if you just told me that was Vivaldi, I'm there.

I'll say, yeah.

The lost concerto found in his attic.

Okay, so Mónica, we have Mónica here, who is a musician and a cognitive neuroscientist and also a playwright.

So how did that sound to you?

I mean, that was Vivaldi.

That's, you've got the syntax.

Yeah, she gave you some up there.

The syntax, so syntax is the-

The syntax, so the grammar.

The grammar.

The musical grammar.

I mean, he captured it perfectly.

The program.

So is this the future?

We just get rid of your musicians now?

No, you, wait, wait, wait, you needed the musician to model your program after.

You needed Vivaldi to imitate Vivaldi.

Yes.

Okay, so, I, but, was Picasso imitating someone else?

Was Vivaldi imitating someone else?

Was Van Gogh imitating someone else?

So this is derivative creativity, not the purest kind of creativity we might seek and value in the human species.

Is that a fair criticism?

There is no purists.

There is no purists.

Creativity.

Creativity is all borrowed.

Ooh.

We all influence each other, so.

So you're citing the cross-influence of everyone.

So whether or not someone even admits it, you're saying it's derived from somewhere.

Absolutely.

Okay, so you're just doing the same thing everybody else is doing, except it's your computer.

Exactly, yes.

Okay, here's what I wonder.

Are you as creative as your computer program is?

More so.

In fact, I went through a lot of AI techniques back in the early 80s and they all failed.

So finally I asked myself, how would I do this myself?

And then I modeled the program on what I would do to do what the program does.

So the program is fundamentally doing exactly what I would do had I been asked to create a 12-movement work by not Vivaldi, but sounding like Vivaldi and naming them Taurus and they're the move.

So in fact, you programmed into the computer a piece of yourself.

In a way, yes.

So this is the early stages of just uploading your mind, body and soul into a computer.

Well, Professor Cope, thanks for joining us all too briefly on StarTalk.

And maybe we can find another way to tap your musical compositions.

So coming up, Bill Nye explains the science of creativity on StarTalk.

We're back in StarTalk, the American Museum of Natural History, right here in the heart of New York City.

We're going to catch up with my good friend Bill Nye.

He sends us dispatches from around the city, and I don't know where he is.

I never know until I see the clip where he is.

But he sends these in, and he knows the topic, and so this topic is the science of creativity.

So let's see what he sent us.

Creativity is important to us humans.

I mean, just think about it.

That's where music comes from.

I mean, how do you do it?

You come up with a new melody and new lyrics for that new melody?

That's complicated, and it comes out of nowhere.

That's creativity.

And I think creativity is very important to human survival.

I mean, imagine being out there on the savanna, getting confronted with a hungry lion.

You got to come up with an escape route.

You got to be creative right now.

Of course, we all know people who have no creativity whatsoever, and those people end up in management.

But for the rest of us, creativity is where all this came from.

I mean, I'm sure it started out in ancient times with vocalizations.

Somebody in the tribe would go, mm, ah, and then someone else in the tribe would go, ah, ugh, and that led somewhere.

That led to a melody, and then eventually, vocalizations that were standardized, and everybody could understand them, and the tribe celebrated that and elevated those people to the point where if people like your melodies and vocalizations enough, they print it on a vinyl record and put it up for sale.

Even those of us who think we have no musical ability at all, we love to sing, because creativity just brings that out on us.

When you're being creative, you wanna tell the world, I'm creative, I'm singing, I'm creative, I'm singing, I'm creative, I'm a sex machine, I'm creative, I'm singing, I'm singing.

You know, there's a big issue probably in other places in the world, but we feel it a lot here in the States.

The funding for arts education is always under stress, and the school boards are wondering, do we cut the art, do we keep the science?

And there's tension, we know this.

And I brought that up with David Byrne, and he had strong views on that as well.

Let's check it out.

In order to really succeed in whatever math and the sciences and engineering like that, you have to be able to think outside of the box, and you have to be creative problems solving.

And the way those disciplines are taught is not totally creative.

The creative thinking...

Not at all.

Not at all.

It's more like this is this, this is this, this is this.

The creative thinking is in the arts.

A certain amount of arts education doesn't mean that your ambition is to grow up to be a painter, but you can use that kind of thinking and apply it to anything else, business, engineering, science.

And be better at it.

And you're better at that.

You succeed more and you bring more to the world because you have these abilities that came from outside of your discipline.

So bringing different worlds together has definite tangible benefits and to kind of cut one or separate them is to injure them and cripple them.

A lot of our creative thinking, imaginative thinking, are relations with one another.

The things that kind of make us different from machines are not all our kind of rational thinking.

That's pretty easy to copy.

It's the other stuff.

To me, imagination or creativity is a kind of inventing and imagining something that hasn't existed before.

In a sense, there's a relationship between that and confabulation and fabulation and making up stuff which is very close to lying.

There's a relationship between creativity and deception.

If you're following me.

No, keep going.

If you're following me.

It's a little bit of a stretch, but I'm thinking to be able to make those kind of creative leaps, you also have to be able to deceive.

There's a bad, there's a dark side to it.

There's the side where you can deceive other people.

You can tell them stories that aren't quite true.

And that's part of what makes us human.

You can make up stories that aren't true.

You can make up stories that could be true and that imagine things that haven't happened yet that are wonderful.

And somehow we navigate between those two things if we have a moral compass or whatever.

But a machine does not have a moral compass.

I tend to believe that a lot of our decision making is not rational either.

We rationalize, we post-rationalize, we rationalize after we've already kind of made the decision.

And kind of an excuse, I did that because...

A well-known effect in psychology.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

They study that.

But the thing is how do you navigate between the two?

If you have too much of one and too much of the other, you're kind of...

You're off the deep end.

Yeah, you're off the deep end.

And at the end of the day, you still have to sell it.

Exactly.

If you're going to pay your rent.

A finger has to stay in reality.

Exactly, yeah.

There are, yeah, crazy artists.

And it's a popular meme.

It's a popular story.

But you have to have some sense to be able to survive, too, yeah.

I basically agreed with everything he said in these interviews.

I mean, I just, he's a deep thinker.

He's creative.

He's educated.

And so his thoughts are put together in ways that really resonated with me.

When I think of culture, what do I think of?

I think you visit other countries, and then they show you what it is that makes them them and not you.

And in almost every case you do this, you are looking at their art, you are looking at their architecture, you are looking at aspects of their civilization that has been empowered by science and engineering.

And so for anyone to say, let us cut art for anything else, suppose they did that back in Renaissance Europe.

What would Europe be without the support and interest in a thriving culture of art?

As we readily spend money to visit these cities and go to their museums to turn around and say, now we are going to cut the art budget here, that makes no sense to me.

And it may be that science and art, which we know sort of go together, the arts and sciences or colleges of institutions, it may be that art and science thought of in that way are the only true things that we create that last beyond ourselves.

Everything else comes and goes.

The leaders, the politics, the economies.

So am I biased?

I don't know.

What I do know is if there is a country without art, that's not a country I want to live in.

There is a country without science.

You are living in a cave.

We measure the success of a civilization by how well they treat their creative people.

And I am just fortunate as host of StarTalk to have two creative people here for this show.

So thank you, Maeve.

Thank you, Mónica.

Thank you, David Byrne, for showing up in my office for that interview.

You've been watching StarTalk from the American Museum of Natural History.

I've been your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

And as always, I bid you to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron