What will the future armed forces of the United States look like? Neil deGrasse Tyson finds out when he interviews former U.S. Secretary of Defense, Ash Carter. Joined by comic co-host Leighann Lord and Michael Horowitz, an expert on military innovation and the future of war, our crew is here to break down the complex role science and technology play in national defense. Learn why DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, was created and how it shares a similar origin story to NASA. Explore bio-warfare, cyberwarfare, artificial intelligence, and nanotechnology. You’ll hear about Ash’s scientific background, including his work in quantum chromodynamics, and how he came to believe scientists have a duty to give back or participate in government. He also reveals the two most important things he learned from his science background. Discover why the U.S. will have to reshape its global defense strategy now that contemporary technology is becoming accessible to more nations. Mona Chalabi drops in to help us quantify the U.S. defense budget, and P.W. Singer, defense strategist and author, joins in to discuss what World War Three might look like in a distant future. Chuck Nice heads into the street to ask people what their favorite weapon of the future is, and Bill Nye boards the U.S.S. Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum to ponder the connections between military guidance and technological breakthroughs. All that, plus fan-submitted Cosmic Queries about death stars, lasers, and much more!

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Welcome to the hall of the universe of the American Museum of Natural History. I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Welcome to the hall of the universe of the American Museum of Natural History.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, and this is StarTalk.

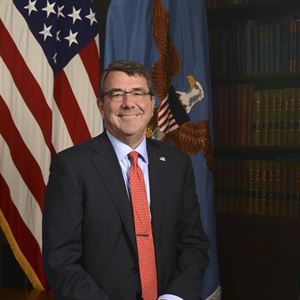

And we are featuring my interview with the US.

Secretary of Defense, Ash Carter, and we talked about the future of science and technology in the armed forces and the defense of this land.

So, let's do this.

With me tonight is my co-host comedian Leighann Lord.

Leighann.

And I've got a special guest, Dr.

Michael Horowitz.

You're an expert, you're on the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania.

That's right.

That's right.

And thanks for coming up for this.

And you're an expert on military innovation and the future of war.

Man, so this, he's the right guy.

Wow.

He's the right guy.

Plus, Leighann.

I need to get his card.

And Leighann, you actually have been a comedian for the Armed Forces overseas.

I have.

I have done several tours.

This is like, all I think of is Bob Hope.

You did what Bob Hope did.

But in a dress, yes.

How do you know he didn't ever have a dress?

Well, I look better in mine.

I think the troops appreciated it, is all I'm saying.

So the Secretary of Defense reports to the President and all of the armed forces report to the Secretary of Defense.

Do I have that correct?

I'm pretty sure.

And what's interesting in this system is that the Secretary of Defense is a civilian.

And so we have the entire armed forces reporting to a civilian, which ensures that it's civilians that create policy and enforce policy.

So that's a, I don't, it's not a unique system, but it's kind of how I'd prefer it.

Civilian control of the military.

Yeah, yeah.

That's kind of a cool fact about it.

And so Ash Carter is trying to transform the modern military.

You know, if you're going to have a conversation with the Secretary of Defense, you think he might talk about how many missiles, how many troops, how many ships, how many guns, and it's not what my conversation went like.

Really?

No, yeah.

That's not where he went, all right?

He knows where things have been, but more importantly, he knows where he wants to take it.

And I asked him all about where the armed forces is headed next in my first question to him.

Let's check it out.

So, Mr.

Secretary, it's great to have you on StarTalk.

I always thought the military should, you know, we had a, you know, once airplanes became important, the Air Force was invented.

But now we have space.

Why isn't there a space force?

Oh, there is a space force.

There is.

But they're under the Air Force.

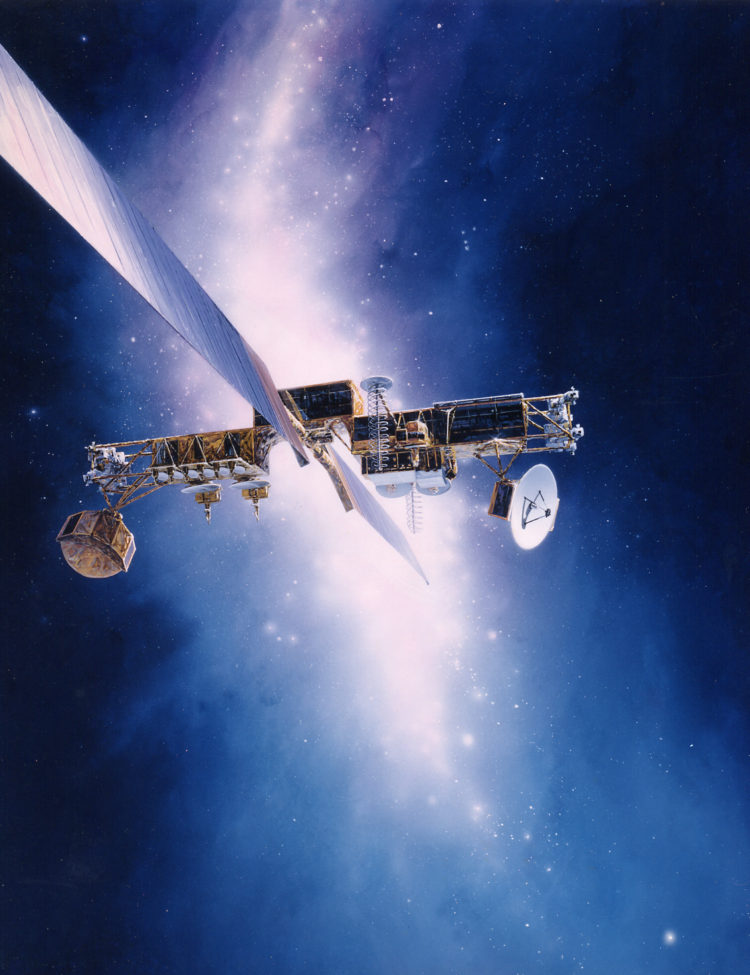

There is space under the Air Force, but, you know, the Army and the Navy and the intelligence community also build, operate satellites.

Many of them are as big as a school bus.

One called the Hubble Space Telescope.

Excellent.

And cousins.

Well, we have cousins of that that point downward.

And, but they're really big.

I wave to them, actually, every now and then when I'm out in the air.

Good for you.

We'll say hi back.

Wow.

Was that your satellite?

Okay.

Oops.

So, I'd like to wave to satellites in case they're looking at me.

Can I believe, for real, that they can resolve the fingers in my hand as I wave?

Not quite yet, but you never know where technology is heading.

What do you mean you never know?

No.

That was not an answer.

You do work for the government.

A, that was not an answer.

But you know.

But he may not be able to tell you.

Okay.

Or then he has to kill you.

Do you have people for that?

Because you watch any Hollywood movie, the satellite is, you know, first it's fuzzy, and you say, enhance.

We know it's all BS.

But, enhance.

No, if you have a photo that's low resolution, you can't just say enhance and have some algorithm show detail where there wasn't detail there before unless you invented it to put it in there.

That's all BS.

The technology that the United States military and many other militaries have is amazing and can do amazing things and you can get great resolution from space looking at things happening on the earth.

But you're going to have to wave for a while before the contemporary technology is going to be able to pick that up.

Plus, while I'm waving, there has to be a satellite right there who's looking at me.

And unless it's geosynchronous satellite, it's got to be passing over for that to happen.

Coverage is one of the biggest issues with satellites.

In the movies, a satellite is always available on demand exactly when you need it to look at the bad guy.

In reality, it sometimes can take some time.

Sort of like in the movie The Martian, when they're trying to get the satellites in position to see where Matt Damon's character is.

So it was intelligently written in that regard.

Absolutely.

Right.

So let me ask.

The space frontier and military innovation have gone together ever since the middle of the Cold War.

I suppose.

There'd be Sputnik, right?

Orbiting Earth freaked us out here in America.

And so it brought in new politics, new military motives, new budgets, new technological developments.

NASA got founded.

So what's interesting to me is once technology matters and space matters, that's just, it's no longer just a measure of troops and bullets and missiles.

It's a measure of technology and science and engineering.

And I was intrigued to learn about Secretary of Defense Ash Carter's background.

He runs the military and he has a background in science.

And this is what makes him a rare breed among politicians in leadership positions today.

So I asked him about his path from science to security.

Science to security.

Let's check it out.

Well, I had some inspirations, as I think most people did, including yourself.

And one of them, I was somebody who wanted to know how things worked always.

And so I ended up studying them.

But that meant you took stuff apart.

No, it was more mental than that.

Although I ended up doing experiments at Fermilab and at Brookhaven.

So I did see some experiments as well.

Later on, not in trouble.

No, no, no, no.

But I did do experiments later, but mostly theoretical physics.

No, it was in the head.

And I wanted to know how things happened to be the way they were and how they worked.

And so over time, I was torn actually between history.

I was a medieval history buff at Yale as well as a physics major, the kind of right brain, left brain kind of thing.

But they both came together in terms of wanting to know how things work.

History tells you why things are the way they are because they develop that way.

And physics tells you why things are the way they are from the point of view of how they work inside.

So I loved them both.

I ultimately ended up with physics.

And now when I was first starting out, I was like most scientists, I was so completely wound up in what I was doing.

I was doing quantum chromodynamics was my thing, which is the force that holds quarks together.

It's a very difficult nonlinear field theory.

It's very hard to solve the equations.

And so we were trying to find, and I did find, some particular kinematic domains in which it was possible to solve the equations of motion and thereby derive a result and test the...

That was all very hot in those days.

It was.

Quarks, what held quarks together.

And also I worked at Fermilab on looking for the W...

Yeah, the W boson.

The first time they went up to 300 GeV energy, really exciting time in particle physics.

But the big problem at that time was this is the height of the Cold War.

And the problem was the Soviet then Soviet Union.

It wasn't every year a height of the Cold War.

There was the Cuban Missile Crisis.

And we now know in 1983, which is right around when this was, that the then Soviet Union was afraid we were going to attack them and they thought they might have to attack us.

So it was a big, big tense time.

But one of the issues was we were building a missile called the MX missile.

And where could we put it where it wouldn't, couldn't be destroyed by a Soviet first strike?

You know, the old logic, still good logic of deterrence, which is if you want to make sure somebody's going to attack you, you need to make sure they know that you can get them back.

So the deterrence works if the other people don't want to die.

Just to be clear.

That has a big assumption in there.

Well, and today we deal with opponents who are not similarly inclined.

That's a different kind of problem.

But anyway, so it was a big technical problem of where to put this.

Then I worked on something that you'd be interested in, or you're interested in everything, but you'd know something about, which is the problem, which we never solved, of shooting down Soviet missiles in flight from space using eczema lasers, free electron lasers, x-ray lasers, neutral particle beams, all these things.

And it was so-called Star Wars, or Strategic Defense Initiative.

And where I first got noticed as a scientist working on national security problems was I wrote a paper based on classified information, but unclassified, therefore widely read, that said none of these things was in the offing.

They were not practical.

That was very controversial at the time, but it was very technically true, as most of the technology community understood.

Yeah, the tech community knew this.

So to your question about inspiration, the generation of elementary particle physicists who were above me, the generation above me that trained me, all had the World War II experience of being part of the radar project or the Los Alamos atomic bomb project.

And they all instilled in me the idea that you had some responsibility to use science for the greater good.

They always told me that I had some responsibility to give back or to participate.

It was a reflex for them, and that is what got me on a kind of trial basis into working on security problems.

So his mentor was Yoda?

I don't know if that's what it sounds like.

It does.

It's like, wow, that sounds very Jedi positive side of the force.

I like it.

So what I'm curious about, Michael, is there was an era, the World War II era.

Basically, the war was won on science.

It wasn't won on troop movements.

It was advanced along via troop movements and guns and, yes.

But science ended the war.

And the Manhattan Project.

It was not only American scientists, in fact, it was mostly non-American scientists brought over in the service of a military cause.

In your studies, do you analyze the role that science has played, does play, should play?

Or the psychology of the scientist who says, no, I don't want to just study in the lab.

I want to help my country.

Because of course, Germany had the same call for scientists.

Come forth.

Help the motherland.

Give me your medical doctors and your physicists.

So they were doing the same thing.

And so this, for me, asks the question, how does or should the government view the role of scientists in this?

I don't think it's possible to understand what a military like the United States military does without understanding its scientists.

You're absolutely right that America's scientific leadership is the underpinning not only of America's economy but America's military.

So given that fact, then that's it.

It's your troops and your scientists mixed together.

That is your war machine in a sense.

Fundamentally, it's how those two things interact.

One of the reasons why the United States is the best military in the world is because of the way that it melds those things together and the way that it traditionally has been able to harness the power of science to empower its troops.

Can we still say that though?

Can we still credibly say that we have the best military in the world?

We have the most expensive military.

Yes, that doesn't mean the best, much like healthcare.

But if I'm understanding the premise of your first book correctly, if you being big doesn't necessarily mean better and smaller and more nimble is able to make changes quicker than we are because we're so invested in one particular direction that we can't shift as quickly as technology.

Well, part of Ash Carter's commentary is whatever is your budget, you need to always stay nimble in how you value what it is you're doing.

He's trying to make sure it's not just ships and planes, that there's a whole, that there are more frontiers.

He'll tell us more about that in the later interviews.

But I'm curious about is you spent a year, you left academia briefly to go work for the DOD.

And what was the, did you feel duty-ous?

Did you, were you called as a sense of honor and responsibility?

If you're on the run, the last place you want to go is the Pentagon, I think.

I think.

You're hiding right under their nose.

But for me, I think it's really important to get out of the ivory tower and given that a lot of my research has been about military innovation in the future of war, the idea of rolling up my sleeves and actually sort of getting to work, both from a learning experience was unbelievable and as a sort of a commitment to service seemed important.

So is it something we should all do?

I think that we would be better off if more scientists took a term of service and spent time in the military.

So one of the largest bureaucracies in the world is the US military, okay?

A bureaucracy usually has a bad name, but it's a top-down system that has layers upon layers upon layers of decision makers.

Is that the right configuration to stimulate the future interest of scientists to join?

I think the challenge is the military is not, and the Defense Department are not the places where, it's not the place where that initial spark of science is going to happen, but it's a place that can cultivate that spark and use it to address some of the nation's largest challenges.

Now a lot of us, and Leighann, in your days growing up watching movies, we all did, movies that had any kind of science or technology in it, typically it was an evil scientist or a mad scientist or a good scientist but co-opted by evil forces.

Basically every representation.

Shady science.

And so should we have to worry about this?

Is that what the Nazis were doing?

Did they cultivate evil scientists?

They didn't think they were evil though.

Isn't that an amazing thing?

You're there and everybody thinks they're doing the right thing.

That's usually when the most evil is done.

Ooh.

You said the English major.

I have no comeback to that.

Wow, dear dire, Neil didn't have a comeback, are you kidding me?

That was just truth.

So Michael, I got a question for you.

Sure.

What is next in defense tech?

Can you tell us without having to kill us afterwards, what is on the horizon that is tech-based that you're going to co-op for the Defense Department?

So here's some things that DARPA and the Defense Department are working on right now that you can read about on the Internet with some degree of accuracy and that I think are really interesting.

One is a fast, lightweight autonomy, the idea of taking essentially miniature drones and having them coordinate with each other to try to conduct surveillance, to try to conduct surveillance in an area and avoid the need to put humans in harm's way.

The second is research on what are called meta-materials.

So think like Harry Potter and Visibility Cloak, but not obviously magical.

This is Stealth 2.0, an attempt to deal with the fact that other countries after two decades have figured out ways to, or figuring out ways to detect airplanes using some of the stealth technology from the 1980s.

So, I love the concept of new materials.

That's a whole frontier.

And you know, our man on the street, Chuck Nice, yeah, he decided to go out and ask people about what their, so their favorite future weapons are.

I don't know if the way they get, is it from movies?

I don't know.

Chuck Nice, man on the street.

Let's check it out.

That's right, Neil.

I'm here in Washington Square Park to find out what people think about the future of defense.

Name the coolest futuristic weapon you could think of, whether it's from a movie or a book or anything.

I think it's the lightsaber.

Guardians of the Galaxy, when all the fighter jets, they all come together to make that huge shield.

That's dope.

Come on, let's have a lightsaber battle right now.

I got these Star Wars bars because you know that the flow is slayer.

Tristan up your mind like the hair on Princess Leia.

So they go against me but they know the flow of rip, y'all.

Trained as a Jedi but grew up to be a Sith Lord.

If you could send robots into war, would you think it's okay for countries to go to war?

If it's just robots going against each other?

Yes.

It'd be better than now, yeah.

Yeah.

Now what if those robots could feel pain?

You can feel pain as a robot.

What would that mean?

No, but they can now.

Would you still send them to war?

No, no, not if something's feeling pain.

No, no, no.

You look like you need somebody to bother you.

You have a 50% chance of dying on the ground fighting clones or an 80% chance of dying in an X-Wing fighter dog fight.

Which one do you take?

X-Wing fighter dog fight.

Because if you're going to die, you may as well die in style.

Yeah, actually, we didn't care.

If you know what I'm talking about, you're a total dweeb.

When it comes to war, the wards, I'm like Neil deGrasse Tyson.

He's a rapper, he's BOB.

You understand, I be holy, because the flow just out the sky.

Yeah, my man's like, yo, yeah, that flow is kind of tight.

So, would you rather go into battle as a genetically modified super soldier, or be a super smart scientist?

Wait, going into battle?

Yes.

A genetically modified super badass soldier.

Really?

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Who needs the science if you've got all the physical gifts you need for battle?

Yeah, how about like a genetically modified person that understands that war is an awful thing to do, and there's many repercussions to it.

Man, that was really beautiful, man.

There you have it, Neil, we're a nation of warmongers, compassionate warmongers.

Well coming up, we'll break down the hard data on what is the biggest defense budget in the world when StarTalk continues.

In the.

From the Rose Center for Earth and Space, we are featuring my interview with the Defense Secretary, Ash Carter.

And we talked about the role of science in defense.

Check it out.

The stuff we do is of greater consequence than defense.

In eras past, remember, that's where the jet engine came from.

That's where space flight came from.

That's where the internet, the integrated circuit and so forth.

I want today's defense department.

Even supercomputing has got its frontier.

Exactly.

For example, when I started my career, one of my inspirations was also a secretary of defense, also a technologist, happened to be a mathematician, Bill Perry.

And he made GPS happen when people poo-pooed it, they didn't want to do it.

And I want today's defense department to be the petri dish for tomorrow's breakthroughs in the same way it was for the generation that trained me.

So these investments, it cost money, it cost taxpayer money, and somebody has to recognize that there's some kind of return on that investment.

And you know, all the personnel, the standing army as it will, whether or not it's the marching army, and the tanks, the jets, the ships, and the outfits.

Oh, the outfits.

It's not a naked army.

All of this.

And it cost money.

Just a bit.

And I want to know how much money.

A whole lot.

So we need some numbers.

And you know what happens on StarTalk when we need numbers?

We make them up.

Oh, that's a different show.

I'm so sorry.

We need some real data.

Fine.

And we got a person just for that.

Called Mona.

Mona, can I get some data, please?

Excellent.

This is Mona Chalabi.

She's a data collector for The Guardian.

And she is an expert in thinking about how to quantify things we otherwise talk about with words.

So Mona, how can you shed some light on this?

So, I would like to quantify the size of the US defense budget, and it's a pretty big number.

It's actually $580 billion.

But when a number is that big, it's kind of hard to get your head around, right?

Not for the astrophysicist.

Is this true?

So, you know, I don't mean to brag.

The stand-up comic is struggling.

I'm good with the $580, but for everybody else.

For viewers, you can understand that number by thinking of it as a share of the total US economy.

So, the defense budget represents about 3% of total GDP.

But then you have a new problem, right, which is, is 3% high or low?

And to get my head around that, I looked at some of the international statistics about how the US compares.

And actually, most countries in the world spend less than 2% of the GDP on their defense budgets.

But there are some countries that spend a hell of a lot more than the US as a percentage of GDP.

Top of the list is a country called Amman, and Amman spends 12% of its GDP on its defense budget.

Yeah.

Whoa.

So what does that get you?

Well, the dollars and cents really, really matter here, right?

And when you look at dollars and cents, instead, the US is top of the leaderboard by a long, long way.

In fact, the US defense budget is more than the next 12 countries on the list combined.

And you're asking what that money buys you.

So I started to look into the defense budget documents, and they are fascinating.

In fact, the second page on that document tells you how much it cost to produce that document.

So just to produce the budget document costs $28,000.

But that's kind of a drop in the ocean, right, when you're dealing with $580 billion.

So when you look at the entire budget, about a third of it goes towards operations and maintenance.

Some of it goes towards investment.

So last year, $7 billion was spent on space-based defense systems.

And a large, large chunk just goes towards personnel, because there are a lot of active military personnel in the US.

1.4 million of them.

Wow.

So like salaries, I guess, they get some kind of money for this.

So that's the standing and marching army that costs any country a lot of money.

So I wonder if the future of this will have less of a standing army and more of a robotic or technological…

Well, do robots cost less money?

Well, they don't need a pension.

They retire and they're just gone.

So, Mona, thank you for shedding some light on the defense budget that we all pay taxes into.

She can go back in.

We're talking about science and national defense.

And I asked the US.

Secretary of Defense, Ash Carter, about the future of artificial intelligence and the tech revolution in the role of national defense as we go forward.

Let's check it out.

When we think of the military historically, we think of troops, movements and weapons and this sort of thing, and ships and jets.

But that's not always the military that we'll need going forward, I'm imagining.

There's cyber warfare.

There's warfare that doesn't involve advancing lines of armies.

That's a very different world.

We are bequeathing our next generation.

So what did DOD used to look like and what's it going to have to look like going forward?

Well, it used to look like planes, tanks and ships.

Now it looks much more like satellites, cyber, signals, special operations forces, meaning very specialized, precise.

So technology changes, the threats change, but people also is important.

This is vital because the thing that makes the American military, I say and it's true, the finest fighting force the world has ever known, is actually not our technology.

That's wonderful and the best.

It is in part the values we stand for, which I'm proud of and are attractive.

That's why we have lots of friends and allies.

I like working with us.

But above all, it's our people.

We have had access to really good people over the last generation.

Remember, it's an all volunteer force.

We don't make anybody into no draft.

My day there was a draft.

There's no draft.

Now nobody has to do this.

They have to want to do this.

And if we're going to have the best in the future, we need to make sure that this is an exciting place to come into.

That gets back to having scientists who can keep us up to date, make sure we don't fall behind.

It means people are sensitive to other cultures and other people because one of the ways that conflict unfolds today, unlike the battlefields of old, it's not by remote control.

You're up close to other people and peacemaking involves understanding other people and connecting.

So we need people of great sophistication.

So in this, when I think of the frontier, where are you guys stepping now that you hadn't stepped before?

There's AI, one of them, or, you know, there are these nanotechnologies, these sort of things.

There's absolutely two.

AI, another way of putting that is the combination of the IT revolution and the neurophysiological understanding we're increasingly having and getting the tremendous power of the brain and the machine together.

That's going to be huge.

Are you stepping there?

Absolutely, we're stepping there.

Now, part of stepping there is you don't have your own labs, right?

So you do.

You do, okay.

We do, but that isn't the main thing we do.

The main thing we do is give money to people who have labs.

Now, why is that?

Because I already have a lab, now you don't have to build it.

And I propose to you and I say, I've got an idea.

And individual people and companies run labs in general pretty well.

And that's not necessarily what the government did.

Remember, the Soviet Union used to try to make everything in the government.

Didn't work out so well for the Soviet Union.

So our way is to feed on the very vibrant technological ecosystem represented by this amazingly innovative culture in America, which by the way is becoming global.

That's another issue for us.

When I started my career in science and technology, most of the technology of consequence was American and most of it-

That's a point of pride, actually.

Oh, sure.

Coming out of the 20th century.

But it's not the case anymore.

The technology base is now global.

The scientific base is global.

It's going to take a different kind of defense department to interact with a different kind of tech base, a different generation of people.

I got to look ahead.

That future generation of people were talking about Silicon Valley and he took a trip to Silicon Valley, when was it, 2015, and they created this defense, did you know about this, Michael, the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental.

That sounds like very...

Yeah, what is that?

What's going on there?

The idea is to try to harness the ingenuity and creativity of Silicon Valley and bring it to the defense department to help with next generation technology challenges.

So, it's the anatomy of the future soldier is a tech expert.

Yes, and another way to think about it is also that this technology, a lot of the technology of the past, like GPS, started in the military and then there were commercial applications.

A lot of the technology we're interested in today is starting in Silicon Valley and the challenge is how do you harness that for the military?

And so, does that mean that there's nothing secret anymore because if it's invented in Silicon Valley, anyone has access to it, the government comes in, now they have the widget and anyone else can get the widget too.

Well, maybe that depends on how early the government gets in because they're courting startups, so maybe it isn't as broad and as public yet.

Yeah, is that, I mean, how does that work out?

It's one of the biggest challenges, as Secretary Carter was saying, in a globalized world where technology is being created for commercial purposes and is spreading around the world for those commercial purposes.

It means a lot more countries are going to have access to that technology in the future, which means you've got to run even faster to try to stay ahead.

So tell me about the integration of AI into the future of robotic technology.

Should we fear it?

I mean, in the movies, if you take a robot and you give it a brain and you give it a gun, then humanity is toast.

Right, because the rational decision would be to kill all humans in the world.

I mean, it says a lot about how we think of ourselves, that when we imagine robots with guns in the movies, we imagine them killing us.

But artificial intelligence can help, as Secretary Carter was saying, it's the fusion of the person and the machine and using autonomy in artificial intelligence to help people make better decisions.

That is the future that DARPA and the Secretary Carter have been pursuing.

DARPA.

Advanced Research Project.

Advanced Research Project Agency.

And what's their budget in a year?

About how much?

Several billion dollars.

Several billion.

That's not even very much.

I was about to say, that's my shoe budget.

And I say several billion, by the way, because the exact amount of DARPA's budget is not always clear.

And when you raise the pitch in your voice with the word exact, that makes it especially funny.

It means we're a few billion off.

So, when was DARPA created?

DARPA was created after Sputnik, actually.

So yes, it smells like a fear we were afraid.

Sputnik was a shot across the bow to America's technology leadership.

And just like with the creation of NASA, DARPA was an attempt to ensure that the United States could stay ahead in developing technologies during the Cold War.

But what about bio warfare?

I think there's a lot of concern about, especially with advancements in synthetic biology, the ability of scientists in even smaller labs in other countries to try to cook up diseases.

And some of that is overstated.

I mean, you can drink the water, don't worry about it.

But there is certainly that fear that definitely exists.

What fascinates me throughout history is the earliest applications of bio warfare, where you would take a rotting carcass and throw your enemies well.

And so that would poison their water supply.

I saw that on Game of Thrones.

Or catapult it over castle walls.

Yeah, catapult a diseased carcass over the walls.

Yeah, so that's in effect bio, biological warfare.

Like version 0.1 of...

Okay, 0.1.

Well, we've been talking about the future of defense technology as it's influenced by science and tech, biotech.

Right now, it's time for the Cosmic Queries segment.

This is where we took questions from our fan base on this topic.

And Leighann, you have the questions in your hand.

I have the questions.

I've not seen any of them.

If I can't answer it, I'll just say I don't know.

Or I'll definitely defer to Mike, but let's go for it.

All right, if you guys are ready.

I will hold myself to very fast answers.

Okay.

All right, let's do this.

All right.

Question one is from Lou underscore keem.

If lasers become the new weapons, what would the armor with, would the new armor be mirrors?

Oh, that's very Harry Potter right there.

Okay.

Not all mirrors reflect all kinds of laser light.

So you could have mirrors and that would reflect visible light lasers, but there are lasers that can laser and other bands of light that could in principle pass through the mirror itself and cook you on the inside.

So, yeah.

So that would be sort of, do we know what laser you're using?

Do we know what kind of mirror to then use?

Then you go back and forth.

You can't, hey, what laser you're using today?

Okay, let me get the other mirror.

I'm not ready.

There's a scene in the remake of the movie, The Day the Earth Stood Still, where Keanu Reeves' character is being laser targeted by an attack helicopter, and he just puts one hand out, the other hand out, reflects the laser's back, and he blows up the helicopter.

Yeah, so that would be a way to send the weapon back to itself.

Well, that has to do with the quality of the manicure.

Yeah, there's it shining.

So, what do you got?

From Predator Baron, two words, Death Star.

Ooh, okay, so, I tweeted about this.

Yeah, okay, it seems unnecessary to completely destroy a planet just to kill the people living on its surface.

If you find a weapon that kills the people and then you get to keep the planet when you're done, why you got to destroy the whole planet?

To teach a lesson to the other planets.

I don't get it.

I don't get it.

Come on, Star Wars, man.

Come on.

But in the last Star Wars movie, okay, they would suck the energy out of a star to destroy multiple planets at once, but I did the calculation.

The energy in a star, you can destroy hundreds of planets.

In that day, only destroyed six.

They didn't do the math right.

It was way more dangerous a weapon than they even imagined for the storytelling.

So somebody did movie math wrong?

Okay, next.

Go for it, next.

Question from Luke the Magic Kid.

Can your mustache protect against Klingon attacks?

Unless I got so close to them that I tickled them with my upper lip.

Tickled them into laughter where they didn't want to kill me.

That is the only way I can imagine that my mustache would protect my life.

Moving on.

Okay, last one.

From Alaska 23, what could an anti-matter bomb do in terms of destruction compared to an atom or hydrogen bomb?

There's no contest.

No contest.

A normal hydrogen bomb, it converts some low single digit percent of the mass into energy.

It's three percent, two percent, five, low single digits.

If you have a matter anti-matter bomb, 100 percent of the matter is converted into energy.

It is a vastly more potent weapon for anything you want to do, or it's a vastly more potent source of energy to drive your starship.

So the future of matter anti-matter fuel is quite fertile.

However, you need the anti-matter available to mix with the matter to make the energy.

What are you going to carry the anti-matter in?

A cute bag from Coach.

Any bag you put it in, it will annihilate.

So you have to make magnetic force fields to contain it.

And it's a containment problem that is still not resolved in our laboratories.

All right.

So what intrigues me is when you have a science background, you see things differently.

And in my interview with the Secretary of Defense, Ash Carter, he told me the two most important things he learned from his science background as applied to his job.

Check it out.

The first is not to take anything at face value.

Don't take received wisdom.

Scrutinize everything.

That's part of the scientific method.

It's extremely important.

That's important for anything.

Whether or not you're in the middle of a scientific environment.

But in government, it's important not to take things at face value.

They're never the way you're told first.

And the other thing that scientists do is solve problems.

And so it's not, it's a, we can do it.

Okay, this is a problem.

Let's solve this problem.

Put those two things together.

So where I've seen scientists in government, they have been largely very successful for those two reasons.

So why don't we have more of that?

Whatever there is, why don't we have more?

I think a lot of scientists don't have the experience that I had.

Which is somebody saying, hey, look, you can participate in public life in a way that will be very meaningful to you.

You don't have to do it for the rest of your life.

The key is they don't have to do it for the rest of their life.

What I'm trying to do...

It's a tour of duty in and out of Washington.

I'm trying to reach out to the scientific community, make sure that relations...

I think plenty of us would welcome that opportunity.

It'd take a year sabbatical and just rotate in and out.

Get to see how the sausage is made.

Exactly, and then they come out and they can turn to their family and say, I did something that really mattered and it was really exciting.

Maybe they'll decide to come back.

Maybe they'll never come back.

That's fine, but they'll have made a contribution.

It's fun to look back at our founding fathers and the scientific literacy expressed by Thomas Jefferson, and especially by Ben Franklin.

He wrote a book called Scientific Researches into Electricity, and it was known internationally for his experiments learning about this new thing called electricity.

A world known as a scientist, independent of how much we know him as a founding father.

And so, that's a different kind of valuation of the role and meaning of science and governance.

Does this mean you might be announcing your candidacy for president?

More on our future of security when StarTalk continues.

We're talking about science and national defense.

And I asked US.

Secretary of Defense, Ash Carter, about the future of national defense.

Let's check it out.

What do you see as the future?

If we start having colonies on the moon and Mars, and other countries do it, this is a very distant future, perhaps.

You know, humans don't always get along.

And so is there some plan to think of space defense in terms of defending other locations in space, rather than just space assets and orbit?

Or is that too far off that you can't worry about that?

No, but it's a, that would be a quality problem to have in the following sense.

It takes a tremendous amount of organization to establish a space colony, which means a lot of people working together.

Like a nation state.

Well, nation states sometimes go crazy.

But, in general, large collectives of people have a certain stability to them.

The thing I think we need to worry about in the future is individuals and small groups.

Now, I'm not just talking about ISIS and Al-Qaeda, and they are today's very important, very dangerous flavor of terrorists.

But there are other people out there also, individuals and small groups.

Now, it's sort of a statistical reality that individuals and small groups show a wider range of behavior, including aberrant behavior, than large collectives do.

And as more and more destructive power through technology falls into the hands of smaller and smaller groups and individuals, we need to worry about that.

So I believe my successors as Secretary of Defense will not only be worried about other nation states and may not be most worried about other nation states.

They may be united with all other nation states, worrying about the aberrant behavior of terrorists, small groups, of individuals who are hyperpotentiated, even though they have crazy ideas, by technology and protecting society from that is, I think, going to be a very important part of our security future.

So, Michael, the future of defense, where's that going to go?

The problem is that people are crazy.

That's the sound bite right there.

Right there.

Okay, let's go for a beer.

We're done here.

That explains everything.

People are crazy.

And if you take a lot of the technologies coming online now, things like 3D printing and drones and advanced synthetic biology, the ability of individuals and small groups of people to blow stuff up has never been larger.

That being said, I think the largest threats out there are still from large nation states.

Okay, so now I've got a guy online, Peter Singer.

Maybe you know the fellow who's actually thought deeply about this.

He's a defense analyst and I think we've got him on video call right now.

Is that right, Drew?

Oh, there he goes, Peter Singer.

Hello, sir, thank you.

Thanks for joining StarTalk.

Thanks for having me.

It's an honor.

Yeah, so you think about the future of defense and security.

Yeah, I work on the issues where politics and technology and national security cross.

And so I've written a number of nonfiction books on topics that range from cyber security to robotics and drones to a new project looking at the future of war that's a smash up between nonfiction but also science fiction.

Basically it looks at what a future conflict would be like ten years out and how it might be fought in everywhere from land, sea, air, but also in places we've never fought before like outer space or cyberspace.

So this would be basically a World War III scenario.

But what about sort of drones and AI and robots?

Do these factor into your storytelling?

They factor into both the real world.

So if we're looking out there at least 80 different nations from the US again to China to Russia to Israel to Saudi, you name it, at least 80 different nations have military robotics programs right now.

Okay, so what happens?

So in a World War III scenario I send my robot to beat up your robot and my robot loses.

Okay, so what?

Does that mean I'm going to surrender to you?

Is that what's going to happen?

You're assuming that you and I aren't also in the fight.

And that's the point is that you'll see robotics being used for everything from surveillance, being used to hunt submarines, but it also doesn't mean that soldiers on the ground, jet fighter pilots aren't going away.

It's actually going to be man and machine working together.

So you're not going to see some kind of easy, clean warfare.

One of the things is certain aspects of support don't change.

And you're not just an analyst and an author.

You've been called to testify in front of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

So you are in there and people are tapping your visions of the future so that we presumably can have a safer future for us all.

Absolutely.

And the hope is that when you're understanding how the wars of the past, but also the wars of the future might start, that you understand that some of them begin through crisis, miscalculation, accidents.

Others reflect a very deliberate set of choices to go to war.

So you mentioned that we haven't had a world war, fortunately a long time, but if you look at the past two world wars, one was basically people deciding to go to war.

The second was a crisis spun out of control.

We're looking at the future, the same thing could happen.

A war could start by two warships scraping paint over some reef that doesn't even show in an article chart or something happening in space, satellites being taken out in escalation, or could people be deciding to go to war?

And so it's by understanding these things, understanding how the technology works, understanding how it doesn't work, what's possible, what's not possible, by understanding you're in a much better position to avoid the consequences.

Well, okay, so that's encouraging.

So Peter, thanks for calling in to StarTalk.

Appreciate it.

I know it's a little late for you, so thanks for doing this.

Alright.

We're featuring my interview with US.

Defense Secretary Ash Carter.

And for that interview, we had some parting thoughts about the responsibility of science and scientists to society.

Check it out.

The citizen scientist that we think of coming out of the 20th century that you were a part of that clearly was imbued with a sense of accountability because it was physics that ended the Second World War.

The Manhattan Project.

And so physicists had a particular accountability and responsibility participate.

Going forward, if it's not about nukes, and it's about biotech or cyber nanotechnologies, then it's not so much the physicist anymore.

It's the tech person who has this accountability to the government.

Do you foresee a rise of the citizen tech expert who would be writing the op-eds of the future the way the physicists of the Cold War wrote theirs?

I don't only foresee it, I see it.

Because the people who are at the frontiers of biology or the frontiers of tech are people who want to make a difference.

And they know they are making a difference.

And they know that they're wielding a technology of great power and great consequence.

Most of them understand that with that comes a responsibility to make sure that that's used for good and not ill.

And I'm trying to tap into that and make them allies, not just of the Defense Department, but of the common good and of peace generally.

And I find the reception as great as it was in my day for a young person like me when I was first told the same thing, you're a physicist, that doesn't mean that you just have responsibility to physics, it means you have responsibility to society.

So Michael, what do you see is the role of the smart tech scientist in the running of government?

I think bridging the gap between academia, between the ivory tower and the policy world is one of the most important things that publicly minded scientists can do.

I think it's something that I wish more did and that I'm excited that Secretary Carter is encouraging that in this rising generation of scientists.

Now there's a movie trope that we've all just grown accustomed to, and that's the scientist turned bad that either wants to take over the world or is controlled by someone who wants to take over the world.

Even if a tiny percent of all scientists are that, if they're really brilliant but evil, that could be devastating to the nation, to the world.

So, in fact, as I understand it, correct me if I'm wrong, after the wall came down in 1989, we tried to find programs to attract the Russian scientists to work on things that were in our interest rather than have them go to rogue nations and then use their intellectual capital against us.

We did the same thing with German scientists after World War II to get them to work for us instead of the Soviet Union.

There it is.

Okay.

So, do we offer to pay off their student loans?

That would sway me, I'm just saying.

Well, that's good.

Now, before we wrap this up, we can't leave without a visit from Bill Ny the Science Guy in his latest installment of Ny Times in the City.

I love him.

To get his take on all of this.

See how he can wrap it up for us.

Let's check it out.

We're aboard the aircraft carrier Intrepid.

It's bristling with amazing innovations of destructive power.

See, ever since the first stone was tied to a stick, technology and weapons have gone hand in hand.

Keep in mind, without military technology, we wouldn't have microwave ovens, radar, weather forecasting, or mobile phones.

It's cool stuff.

Take this missile, for example.

It finds its target with radar, microwaves, just like in your oven.

This missile finds its target with heat.

Argon gas gets a special sensor cold really fast, and the heat passes through a special lens, and this missile can seek its target with heat.

It's the same thing that makes your remote control control remotely.

Our desire to be best on the battlefield has given us all this amazing technology.

But wouldn't it be something if we could have all this wonderful technology without having to invest so much of our intellect and treasure preparing for war?

Back to you, Neil.

Yeah, that's the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum, parked on the Intrepid aircraft carrier, parked on the west side of Manhattan.

So Michael, where do you want to leave us?

What is the summation of all the wisdom that you have gleaned from the books you have written, from the courses you have taught, and from the research you have done?

Can you distill it into the essence of what we need to hear in this time?

Into a tweet.

It's a haiku, yes.

What do you have?

When Americans roll up their sleeves and work together, we can do just about anything.

And that's what Secretary Carter is trying to encourage the United States to do.

And I think that's what we need to do in an era of emerging technologies and global challenges.

Do you think we'll succeed?

Nah.

I would never bet against the United States of America.

Oh.

So, you know what I think about?

I think about, you look at how much we invest in the capacity to wage war, and I'm a little disappointed that there isn't at least as much effort invested in never having war at all.

And is it always that we will never have war because I am so powerful, you won't even try to attack me?

Or maybe there's some other investigations that can occur where the idea of wanting to attack someone never even comes up.

If you look at the history of war, many of the causes come about because people differ in their worldview, and they will not have a conversation to solve it.

In other cases, there's scarce resources, and it's a fight for the high ground or to control the resources.

When I think of space, I think of a place where everywhere is high ground and there is unlimited resources, so that perhaps the fact that humans wage war is the consequence of the fact that we live on the surface of a finite place we call Earth.

That if we explored the universe and the universe were our backyard, what would you ever fight over?

There are plenty of planets, plenty of stars, unlimited energy, boundless natural resources contained in asteroids.

Elements we call rare Earth on Earth are not rare in space if you pick the right asteroid.

So maybe a future in space investing $600 billion will in fact be the end of all wars.

And future civilizations will look back and say, how could humans have been so trite to not have had the cosmic perspective enabling them to see the value of peace as even greater than the value of defense?

That is a thought from the universe.

You've been watching StarTalk.

I've been your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, bidding you to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron