About This Episode

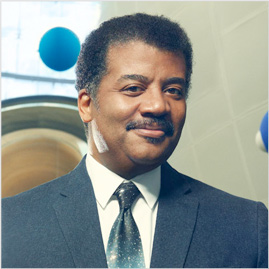

On this episode of StarTalk Radio, Neil deGrasse Tyson explores the science and psyche of filmmaking with auteur filmmaker Darren Aronofsky. Aronofsky is known for making films that are often surreal, melodramatic, and psychologically thrilling including Black Swan, The Fountain, The Wrestler, Mother!, Noah, and Requiem for a Dream. Neil is joined in-studio by comic co-host Paula Poundstone and astrophysicist and StarTalk geek-in-chief Charles Liu, PhD.

You’ll find out about Darren’s early exposure to the wonders of mathematics, including some of the theories and ideas on the fringes of the subject. Explore his interest in the Fibonacci sequence. Our panel investigates how people can sometimes over-manipulate numbers to find meaning that isn’t there. Learn more about “cosmic geometry.” Charles explains why mathematics goes beyond just numbers.

You’ll hear how Darren became interested in filmmaking. Discover more about the importance of storytelling in the human experience. Darren explains why the process of getting an audience into a film must be a step-by-step process. Charles tells us why using stories to explain science concepts is a better way to have students engage in the material instead of just sharing the information.

Neuroscientist Heather Berlin, PhD, drops in to help us explore the psychological seduction of film. Find out if technology will ever allow us to see inside someone else’s mind…or if it already has. We ponder death and whether Western culture should treat death differently. We also ask, “If science could prevent death, should it?”

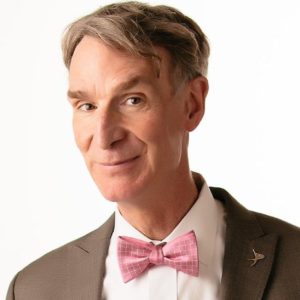

You’ll hear about Darren’s series One Strange Rock that encompasses the beauty and fragility of Earth. We answer fan-submitted Cosmic Queries about our Moon and Jupiter’s moons, and Darren even asks Neil his own question about the Moon. Neil and Charles geek out over the weight of Thor’s hammer, how much water would have rained down during Noah’s flood, and the size of Icarus’s wings. All that, plus, Bill Nye sends in a dispatch to celebrate the art of motion pictures.

Thanks to this week’s Patrons for supporting us:

Sebastian Seilund, Ian Schulze, Heidi Lynne Makela, Calvin Mitchell, Sinai Coons.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons and All-Access subscribers can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTFrom the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, and beaming out across all of space and time, this is StarTalk, where science and pop culture collide.

I’m your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

And tonight, we explore the extreme, from the depths of the human psyche to the cold vacuum of space.

So, let’s do this.

So, my co-host tonight, Paula Poundstone.

Welcome to StarTalk.

It’s been a big fan of yours for a long time.

And you also had a recent book, The Totally Unscientific Study of the Search for Human Happiness, where you actually do experiments, even though you say it’s unscientific.

I do experiments.

Every chapter is written as an experiment.

I do experiments with things that either I or other people thought would make me happy.

All right.

Also joining us is StarTalk’s resident geek-in-chief, Charles Liu.

Professor of Astrophysics at the City University of New York in Staten Island.

We’re featuring my interview with Oscar-nominated director Darren Aronofsky.

He’s the man behind popular films like Black Swan, Noah.

But his directorial debut was for a film called Pi, as in the mathematical constant.

3.1415926535, et cetera.

I’m good for eight decimal places.

That’s it.

3.1415926.

That’s all I’m good for.

You know what?

I think that’s plenty.

You know, most circles, you go further than that.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

We’re good.

We’re good for most circles here.

So because of this, you know I had to ask him about any sources of mathematical inspiration in his life.

So let’s check it out.

In high school, I had a really great math teacher, the head of the department, Mr.

Schneider, taught this weird elective, which was like, I guess, mysticism in mathematics or something.

We learned about Pythagoras and his cult running around, really fascinating stuff.

But he also talked about Pi and how…

Because we remember Pythagoras with the Pythagorean theorem.

But there was a whole subtext to what was going on in his life and his followers.

They were monks or something.

So that was interesting.

And then all these weird kind of mystical ideas that, you know, if you actually take the height of Giza versus the width of it, you get the…

I don’t know if it’s true.

You get a more accurate number of Pi than what the Egyptians were using.

So he was just turning us on to these different ideas.

I mean, now it’s become really popular.

When I was doing Pi, there were no books on, you know, cosmic geometry and all that stuff.

There was very few books out there.

Now it’s become…

People are really into all those connections.

It’s like math being the language of nature.

And repeating patterns in different shapes.

And that, you know, it became a big theme in Pi, the spiral idea that connects us.

So you had Pi on the brain.

And from what I understand, you were enchanted by Fibonacci.

Yeah, I mean…

It’s weird.

This is my weird connection to it.

My zip code as a kid in Brooklyn was 1-1-2-3-5.

Ooh.

Right?

That was my zip code.

So there’s 1 plus 1 is 2.

And then 2 plus 1 is 3.

And then 3 plus 2 is 5.

Right.

So 1-1-2-3-5.

That was my zip code.

That is crazy.

So, fifth grade.

Fibonacci zip code.

So Charles, the film Pi is about a mathematician’s obsession with numbers.

Yes.

Can you relate to this?

Absolutely I can.

They are so cool.

Not to mention, by the way, my wife is a mathematician and my son, one of my sons, is studying to be a mathematician.

They’re fascinated by numbers too.

Except that mathematics far exceeds just numbers.

What’s cool about numbers is that you can get lots of neat things happening and you don’t really know why.

And that excites people and it triggers imagination, makes them think about mysteries that you don’t understand.

Yeah, but you can over-manipulate numbers and think it has meaning.

All the time.

People do it all the time.

And it’s actually a kind of a caution that we have to make sure that things like that do not overwhelm your legitimate understanding of the limitations of the patterns you see.

What do you mean manipulating numbers?

Well, so you can measure things and then work for hours to combine numbers or divide them or multiply them and come up with something that you deem significant.

And then you assert that the object had that significance buried deep within it.

And then you extracted it by having manipulated measures of that object.

I would never do that.

Just to be clear, never.

So explain, Charles, the Fibonacci sequence or its relevance to nature.

Sure.

Fibonacci, just as you described in the clip there, you go one, one, two, three, five, eight, etc.

Adding the two previous numbers to get the next number.

It turns out that as you go forward, the numbers grow very rapidly on an exponential scale.

And as the sequence heads toward infinity, the ratio between each number and each successive number approaches what we call the golden ratio, which creates a spiral pattern that can go on into infinity always repeating itself in a very beautiful and interesting way.

Darren also mentioned something called cosmic geometry.

Do you have any sense?

It sounded a little mystical to me.

Yeah, cosmic geometry or sometimes known as sacred geometry is to shapes the way that say numerology is to numbers or astrology is to stars in the sense that people saw so many cool things about the universe or about the world around them that they could put in the context of shapes and structures that they thought surely there was something mystical, perhaps even divine.

Deeply, deeply significant.

Yeah, it turns out that there is not because you can always find ways to relate shapes to one another to the things that we imagine, we see.

In the end, almost all of that is coincidence.

But it’s a good place to start, to start thinking about things.

Relationships.

Relationships that eventually lead to scientific truths.

Eventually.

Eventually, but not right away.

Well, after I got the scoop about his film on math, I asked him how he found his path to become a filmmaker in the first place.

That’s always a fascinating story.

And I got it from him.

Let’s check it out.

I graduated high school early and I was backpacking around Europe.

And I ended up in one of those finding yourself.

Is this what you were doing?

I’m still doing it.

Still haven’t found it.

And then ended up in Marrakesh and Morocco and the Jemma, the big square.

You’ve been there?

No.

It was an amazing place.

And they basically, you know, at sunset, you got snake charmers and you have food hawkers and you have all different types of people and they were storytellers.

And I remember pushing through this crowd and seeing this old man on a cane speaking in his language.

I didn’t understand a word, but everyone, like as he moved, he just became this giant.

And I was like, oh, it’s storytelling.

So that was evidence for you.

The power of storytelling was not only international, but possibly primal.

Yeah, and I believe that.

And it goes beyond language.

And I mean, that’s the beauty of a film is that you can watch a seven-year-old in Iran or an 80-year-old in Scotland.

And if the film can take you into their subjective experience, and then you suddenly realize we’re all human going through the same types of challenges in their own unique ways.

But you can connect with any character on the planet.

Wouldn’t it be sad if it turned out that the guy he encountered in front of the restaurant in Morocco was just listing the dinner specials.

And then he launched this career unnecessarily.

Well, somebody had, Charles, he says stories.

Yes.

Darren says stories are a way to connect anyone on the planet.

Yes.

So you are a professor.

Yes.

I was once a professor.

I’m not anymore.

Do you use storytelling to help your students connect with science?

All the time.

Really?

Yes.

It is pedagogically wise to do so.

In fact, studies have clearly shown psychologically, educationally, et cetera, that human beings are very much interested in narrative.

If you can tell a story about the universe, if you can tell a story about whatever you’re trying to describe, it’s much more likely to be both remembered and make an impact than if you just list the information.

So what’s more universal, math or stories?

Will aliens like stories if we meet one?

You know what?

It would be cool if we saw aliens and they got around a campfire and were telling stories to each other.

I’d say this.

It’s like asking what’s more universal, your right leg or your left leg.

Oh, your left leg.

Then that’s the answer.

When we created the constellations, how do we remember these weird patterns of stars?

Unless you tell a story.

Oh, there’s Orion hunting or defending himself while the dogs are behind him and the bull is in front of him, things like that.

Telling the stories may indeed be the way that we connect with aliens in the future.

First, though, with the math, right?

Once we send them a Fibonacci series of bleeps, then they know we understand something about mathematics.

And then we can tell them, let me tell you about what my mother-in-law Glorpfla did yesterday, you know, with the roast.

So that’s an alien grandmother name?

Yes.

Glorpfla.

You thought about this.

Okay.

That’s part of the story.

You know, this is like we haven’t even met the aliens yet and already we’re stereotyping.

Next, we’ll break down the psychology of facing extreme situations in film when StarTalk returns.

This is StarTalk.

Welcome back to StarTalk from the American Museum of Natural History.

We’re featuring my interview with director Darren Aronofsky.

And I asked him how he uses film to explore the far reaches of human experience.

Check it out.

I think the idea is to take people inch by inch, step by step, into extreme places.

I mean, that’s what I’ve done in a lot of my work is like…

Wait, that’s a…

I gotta hear that sentence again.

Take an audience, inch by inch, step by step, into where?

Into very extreme places, because I think that’s sort of showing the range of humanity.

I mean, I end up telling the story of these characters that they don’t have ordinary journeys.

They’re definitely going somewhere really far.

So, you know, I wanted people to understand Natalie Portman, the ballerina’s kind of motivation, her urge, her dream.

She slowly gets possessed by this need to be perfect and this need to succeed.

That’s the inching of the way.

It’s inching.

You take little steps.

It’s like in Requiem for a Dream, you see what I loved about the book is that it was these two stories.

One was like a typical drug story of young kids and one was an old lady who was just sort of addicted to a dream.

And how being addicted to a drug could be the same as being addicted to not eating a chocolate because you want to lose weight.

And how that kind of conversation in your head is the same sort of biochemical conversation that you’re…

You’re grappling with, yeah.

Yeah, you’re grappling with.

And that to me was fascinating, but to show that you have to be…

It’s really inch by inch.

You see her look at the box of chocolates, you see her try to look away, you see her look back.

Then you do something where the chocolates get a little more exciting through sound and design.

And you slowly can, you know, show the audience of what she’s feeling.

So it’s a psychological seduction.

Yeah.

Exactly.

Joining us to discuss the psychological seduction of film is neuroscientist Heather Berlin.

Dr.

Heather Berlin, a friend of StarTalk, your assistant professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine Mount Sinai.

And your research focuses on a range of neurological disorders.

So what makes a movie a psychological thriller?

Well, I mean, basically the action, the main action of the film is happening usually inside the main character’s mind.

And so the action doesn’t take place externally, it takes place internally.

And often there’s some ambiguity between either for the audience or for the lead character between fantasy and reality.

And that sort of takes you on this journey.

So when you’re observing it, you don’t know all the details in the head, but the director is trying to feed it to you in little bits.

And so there’s mystery and a little bit of terror.

Yeah, I mean, any time you get deep inside somebody’s psyche, there’s going to be some terrifying bits.

You want to sort of be aware.

I mean, there’s a reason why we have these fronts and why we present ourselves in certain ways.

Our facade.

Absolutely.

Because if you really get into the deep crevices of the mind, there’s going to be some dirt in there.

Would you say that the emoji movie is an example?

It’s a deep psyche of the poo emoji.

Is that what you’re referring to?

Yeah.

Yes, I’ve thought about that.

The psychological states and conditions he’s explored have include obsessive compulsive disorder, addiction, narcissism, perfectionism.

You’re familiar with all of these.

Yeah.

I mean, throughout his films, he always kind of also plays upon hallucinations and delusions.

But in particular, obsessive compulsive disorder, perfectionism, black swan, obsession and pie.

Even in The Fountain, the lead character is obsessed with trying to find a cure for…

Age or brain tumors.

And addiction.

I mean, it was really interesting what he said because it’s true.

I study behavioral addictions, like things like being addicted to food or gambling or the internet.

And what we find is that the same neurocircuitry is involved with behavioral addictions as is involved with addictions to drugs, to chemical addictions.

So it’s true.

And that’s why that film is so amazingly well done is that it’s the same brain chemistry involved.

So do you think technology will ever allow us to see inside of someone else’s mind?

Or generating the visualizations of dreams rather than just knowing that they’re having a dream through rapid eye movement or something?

I mean, the thing about the mind is that it’s subjective, right?

So the only thing we can know objectively is which neurons are firing when you tell me you’re having a thought of, let’s say, seeing a rose.

So one rate limiting factor is we’d have to map out every neural correlate of every thought you’ve ever had, which is a pretty difficult task.

But even if we could do that, right, then it would just be sort of a computer simulation.

We’d say, ah, that neural activation looks as if he’s imagining a rose and then we can sort of create an image of that on a computer.

So we never can get directly into anybody’s mind.

Oh, so what you’re saying is you studying the connection between my seeing a rose and the neurosynaptic response trains you to draw a rose based on this impetus, based on this impulse.

Exactly.

But what you’re telling me is you can never look into someone’s brain and just draw the picture that they’re seeing?

Why not?

Well, first of all, there’s nothing.

The brain, there’s darkness in there.

You never actually see anything.

You’re thinking there’s like a little camera?

No, that’s funny that you think that because you’re a science guy.

No, it’s all like bloody and gooey in there.

There’s no…

I mean, I look inside people’s brains all the time.

You know, I’ll sit in on neurosurgery and we can…

Actually, a patient will be fully awake and we can talk to them and be looking inside their brain and manipulating things at the same time.

Do you ever see any popcorn in there?

That’s the only way to know for sure.

Loose chains would be nice.

Exactly.

Car keys, yeah, the house keys.

How do they do?

I’ve read about that before.

How do they do that where somebody’s having brain surgery and you can talk to them?

How is that possible?

Well, basically, there’s no nerve endings in the brain.

So actually, the brain, you don’t feel anything.

There’s no pain in the actual pain center.

There’s no artistic fingers in somebody’s brain.

You can do whatever.

The only thing is you have to numb the scalp.

And once you get through there, you can do a lot.

So what we do is we actually can map out a person’s brain.

You are speaking way too glibly about going inside somebody’s head.

How do you feel the scalp?

Just remove it, put a little anesthesia, and then you just go in the stand and poke the brain.

And that’s all.

Well, all this is kind of new to him, who only a few moments ago thought there was a screening room.

Would either of you…

Paula, would you or Charles allow her to put you on one of her machines to see what you’re thinking?

I 100% would.

100% totally.

No, I don’t want anybody cutting into…

First of all, my scalp is really sensitive.

I don’t even like to comb my hair.

So just cutting my scalp right off the bat.

Do you think your field is just not mature enough yet to come to the…

just to hook somebody up and say, here’s the picture that they’re looking at?

Look, we’re starting…

There are experiments now where, for example, I can show you a picture of a house, let’s say, versus a cat.

And I can see…

We can do neuroimaging and see what your brain looks like when you’re viewing either one of them.

Then I can put you in a scanner and say, just imagine something.

Don’t tell me what it is.

And then based on that, we can predict whether you’re imagining a house or a cat.

So if you had a patient and they just all day long thought, cat, house, cat, house, then you’d be…

We could pretty much read their minds at that point.

So basically we could read a simplistic mind.

Yeah, well that is exciting.

Wow.

So Aronofsky is also known for exploring taboo topics in his films.

And in The Fountain, his film from 2006, he confronted our resistance to the process of death.

And I asked him about that, so let’s check it out.

I think there’s something spiritual about our journey towards death that the West has turned their back on.

It’s not something we respect.

It’s not something we study.

It’s not something we teach.

We try to avoid it at all costs.

At all costs.

And yet, you know…

Literally, at all costs.

And we lock up our old people.

We don’t take care of them.

And it’s a lot of suffering as opposed to easing people and helping and taking people on part of their journey.

You know, it’s funny as when we’re in kindergarten, we collect the fall leaves, a sign of death as this sign of beauty, but we can’t sort of apply it back to, you know, our own kind of reality.

Or we decorate with them.

We decorate with them and we glorify, you know, this cycle that’s happening, which you have the beautiful green that turns into brown, becomes bare.

And that idea of the cycle…

Rebirth.

And recycling, which is really what’s happening.

You know, even as we’re alive right now, we’re recycling each other and this world.

So, look, I’d like to live an extra 10, 15 years in a healthy way, maybe even more for my son and stuff.

But I think a bigger part of the conversation should be about how, you know, what is life without death?

It’s a terrifying idea.

And death doesn’t really need to be terrifying.

It can be something that’s beautiful.

Heather, why are we so resistant, maybe just in the West, but perhaps in general, why are we so resistant to the inevitable reality of death?

Well, you know, there are other species that sort of understand death.

There was a recent story of an orca that carried her calf around for weeks.

Yeah, orca that had died and carried it around for weeks.

So they have some idea of death.

But I think we’re the only species that really can anticipate our own death, which leads to anxiety, right?

And even religious people who supposedly believe in heaven, so you shouldn’t be scared of death because you’re going to go to some beautiful place.

They don’t want to die either, right?

So there’s something about, I think, losing your consciousness, your awareness.

So even the sort of comfort in, oh, maybe our bodies are going to be recycled and turned into something beautiful.

But if my consciousness isn’t there for eternity, that’s quite frightening to people.

So, but we’re fascinated by death in movies and news stories, and what does it mean to be fascinated by something that we fear?

Well, I think that it’s the great unknown.

It’s this great mystery.

And so films and media and ways can either interpret what happens in death to give us comfort.

I mean, The Fountain kind of was an example of that in a way that it’s not just there is nothing.

There might be something.

There might be something spiritual.

And so if we can visualize that and imagine what it might be like to die, that might give us some comfort.

And that, I think, is our obsession with it.

I think kids are fascinated with T-Rex among all dinosaurs because they can be eaten by T-Rex.

And in the universe, they’re fascinated by black holes because you can be eaten by a black hole.

I think it’s fascinating when children first realize that they’re going to die and how they interpret that.

And for me, that’s why I became a neuroscientist, because when I first realized at the age of five I was going to die, I thought, can I keep my thoughts?

How can I keep them?

Oh, my brain makes them.

How does my brain make my thoughts?

And how can I keep them?

You have a very advanced mind.

I put Play-Doh up my nose.

So Charles, how do you view death coming from the universe?

Everything dies, right?

Planets die, stars die, even black holes die.

That’s very holistic.

It is.

So in my sense, the concept of death is really a transition from what you are now to what you will be in the future.

So in that sense, if you’re comfortable with that, there’s nothing to fear.

I think this idea of being uncomfortable with death is exactly what Heather is talking about.

We’re afraid that we won’t have a legacy, that eventually no one will remember us.

The things that we value from others, someday no one will value us for it.

And so that’s our search for eternity, for longevity, for something in the future.

If you think astrophysically, that the idea, well, you are going to change, but somehow what you were will become something else that may be even more grand and more beautiful, don’t worry about it.

But I don’t even think it’s sort of that’s a bit of a narcissistic view, like I want to be remembered.

But I don’t, that’s not why I want to live.

I just like experiencing life.

I don’t even care if I’m remembered or whatever, but I want to smell the rose and you know, see my children.

And so I just like the experience of being alive.

Paul, are you afraid of death?

I don’t even like it when my turn is over in a game.

Heather, I got one last question before I let you go here.

If science could prevent death, should we?

I like that question.

Well, you know, insofar as death is often caused by some sort of illness or disease which involves human suffering, I think if there’s something that we can cure, a preventable disease, we should.

And as we start doing that, life will inevitably get longer and longer.

I mean, we’re already living way longer, even just for the invention of antibiotics, right?

And so I think for sure we should do that.

And if it becomes that we figured out a way to keep us alive indefinitely, then maybe it’s a person’s choice when they want to go.

And they’ll feel bad for all the people that we lost who didn’t have the option to stay alive.

And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it, other than the fact that it might get a bit boring after a while.

And then you can choose to go.

But it would be nice if it could be your choice when to go, rather than having some horrible disease.

If we choose not to die, we’ll need more planets.

Yeah, no, I mean, that’s where you come in, obviously.

Are you in charge of that?

The population growth assumes people die, mixed in with the birth rate.

And if you don’t die, you’re still making babies, we need another planet.

We need a bigger planet.

There’s probably at least a trillion planets in the Milky Way galaxy alone.

I think we’re cool.

But the other thing, you guys, when you’re talking about these lives that go on forever, are you talking about having more of your 30s?

Or more of your 90s?

Or are you talking about functioning with a body?

A lady just died who was 117, she was the oldest woman in the world.

She called everyone kiddo.

Are you talking about extending the years where you’re 120?

Because by the way, count me out.

What’s wrong with 120?

I don’t think you’re in great shape at 120.

It doesn’t have to be the case.

Studies show that we humans have a greater bias toward age than anything else, be it race or gender or anything like that.

Why should we feel that?

Bigger bias against age.

Right.

Why should we have that bias if we can live forever?

It no longer matters.

Age is just a number.

How many experiences have we had?

How many places have we gone?

How many people have we met and enjoyed the company of?

That becomes the measure and not how long you’ve been around.

Plus, based on the STD rates in nursing homes, old people are having a lot of sex.

They’re going out with the bangs.

Heather, thank you for joining us tonight on StarTalk.

Up next, we learn some of the science behind Hollywood’s movie magic when StarTalk returns.

You’re listening to StarTalk.

We’re featuring my interview with filmmaker Darren Aronofsky.

And I asked him about the movie magic behind the celestial objects in his film, The Fountain.

Let’s check it out.

Remember the cloud tanks, like in the old Spielberg films where the clouds are coming up over, you know, over the neighborhood and stuff?

That was basically pouring ink and milk into actual tanks, and they would photograph it, and then they would combine them.

And so every single effect in The Fountain is photographed.

All of the nebula, all of that stuff, none of it is CG.

I mean, most of, like, the celestial scenes in, including the supernova, were through a microscope.

And that was just basically two or three different chemicals reacting, and when they, you could picture, you know, dropping a little.

That’s brilliant.

That’s brilliant.

And it came out great, and you get this texture and weirdness that is…

Because I didn’t think to think about it.

That’s a good sign.

How was that representation of moving through a nebula?

Was it okay?

I get B plus.

Well, in addition to the math connection that Darren made in the movie Pi, he also featured an ancient board game called Go.

And since then, the company Google created an artificial intelligence project called AlphaGo that learned the game with such proficiency that it can now beat any human player.

So I asked Darren about this.

Let’s check it out.

The main character in Pi was also a Go enthusiast, is that right?

Yeah.

Okay, what did you know about Go?

I didn’t know much.

So you make a character who does?

Well, that’s the cool thing about making films.

They basically take three, four years.

So it’s almost like another university degree each time I do something.

But it gives you the opportunity because you get to talk to experts.

I’m sure I’ve tried to call you about certain things and just get insight into the research we’re doing.

When I did The Fountain, I got to hang out with brain surgeons and actually watch surgeries.

So that’s one of the great gifts of filmmaking is that you get to sort of be a dilettante through all these different worlds.

So in the game Go, this predated, I think, AlphaGo.

Yes, absolutely.

From Google as the AI.

Yeah, that beat.

So did you have a reaction to that?

The AlphaGo.

There was something interesting that came out that was fascinating.

Not only that they beat a master at something that no one thought would ever happen, but the way the computer played undid thousands of years of tradition in the way it was played, so that now it’s affected how people play each other.

So the AI actually has changed us as people, not just beating us.

It’s actually taught us something to think about it in a different way.

You know, I think in order for AI to play a game like that in a lifelike way, it would have to be able to flip the board when it knows it’s about to lose or yell at the other player and say, it’s your turn, will you go?

That’s an important part of any board game.

You need that.

You so need that.

Charles, our geek in chief for StarTalk, give us a quick overview of the game Go.

Sure.

Because it’s not as popular here in the West as it is in the Far East.

But it’s a long-standing, tremendously tradition-based game.

It was invented more than 2,000 years ago in China.

The Chinese name for Go is Wei Qi, which literally means surrounding chess.

Your point is to try to make sure that your pieces are cornering or surrounding your opponent’s pieces top, bottom, left and right.

And because it’s such a big board and because the rules are so simple, it has been calculated that there are 20 billion, trillion, Google possible legal board combinations.

So it is a remarkably difficult game to grok.

You invoke the word Google as a number, not as the name of a corporation.

One with a hundred zeros after.

But in reality, it’s actually very hard to calculate the exact number of possible outcomes because the numbers are so huge.

We can’t wrap our heads around them.

Even the number of atoms in the Milky Way galaxy is far smaller than these combinations.

So it’s really, really hard.

Well, coming up next, we answer your cosmic queries about the origin of the moon when StarTalk returns.

This is StarTalk.

We’re featuring my interview with filmmaker Darren Aronofsky.

And he recently produced a science series for National Geographic called One Strange Rock about our home planet.

Let’s check it out.

We were trying to do this 10-hour portrait of the planet that basically showed how amazing all of these different systems have to work and connect to make life possible.

So we have astronomy, we have earth science, we have chemistry, we have biology, we have anthropology and sociology.

And kind of blending it as a portrait of all these different ways and different connections between them.

But the kind of big question was how we were going to unify it.

So we in the room had this idea about going to astronauts who actually have this amazing thing called the overview effect.

They all have this similar thing happen to them where they start to see the planet as one system.

And they start to see themselves not as Americans or Iowans.

They start to see themselves as Earthlings.

And I found that really an inspiring idea.

So One Strange Rock is just this kind of beautiful portrait of all these systems working together in ways that are just fascinating.

Charles, in your head, what makes Earth One Strange Rock to you?

You do, Neil.

I do.

And me and Paula and all of us and all the algae and all the lobsters.

The concept of life as we know it makes this rock so much stranger than any other rock we have ever found or may ever find.

So One Strange Rock is told from the perspective of astronauts looking down, but we as astrophysicists, we look up.

Yes.

But I think we have the same view without having the benefit of going to space.

I think so.

But there’s surely some benefits from looking down.

What would they be?

Well, sure.

When we are trying to understand the unknown, we look around us to find analogs and then send them forward.

The physics in the kitchen, the chemistry in a pond are the kinds of physical and scientific processes that happen out in the universe, on other planets or in other galaxies.

So we look down to us, and the more we understand about where we are now, the better we can understand what’s out there.

Charles is getting all deep.

Charles, what are the physics in the kitchen?

Well, say you take your frying pan and you put it on the stove.

It gets hot because the burners are touching the stove and the burners on the stove are then touching the pan.

That’s called conduction.

That’s conduction.

Furthermore, once you put the water or the sauce in the pan, the liquid in the pan starts moving around in pieces, kind of moving energy around.

That’s called convection.

And then finally when it gets hot enough that you put your hand over the pan and then you have the sauce that’s radiating heat out onto your hand.

So that kind of convection, conduction and radiation is exactly what happens inside the sun.

The way that energy comes out of the sun is first radiating from the nuclear-powered core, thermonuclear-powered core, and then out-convecting in the interior of the sun, and then being eventually radiated out past the surface to the earth, to our faces, which then can touch other things and then conduct that heat.

Can you do anything with peanut butter and jelly?

So Darren Aronofsky, he may have tackled big questions about earth in the show, but he had a question for me about the moon, so let’s check it out.

The moon is a piece of the earth, right?

Mostly, yes.

So why is it all gray?

The question is, if earth didn’t have life, what color would it be?

Maybe that is what you should ask.

So the moon is made mostly of the material that is earth’s crust, our crust and mantle.

And our best ideas are that there was an early in the solar system, there was a collision between a sort of a proto planet and earth, and it side swipes earth.

And if you side swipe earth, and earth has already separated out its ingredients, the heavy things had fallen to the middle, that’s why we have an iron core.

We’ve all heard this.

Maybe you didn’t think through why that’s so.

There’s a point when earth was molten.

When you’re molten, heavy stuff goes, falls, and lighter stuff floats.

So the iron goes to the middle, the lighter stuff, such as what we call the silicates, which makes rock, goes to the surface.

And now something side swipes us.

It’s not reaching into the core to get it.

So you have all of these silicates in…

We think we might have had a ring.

A Saturn-like ring for a while, briefly.

It would have been totally fun.

So people ask me, if I were to go back in time, what would I want to witness?

Just to see the ring.

I want to see the formation of the moon.

Take me back, put me at a safe spot.

If you get a bucket of popcorn.

And I’m watching that.

So it side swipes.

You get a ring.

The ring coalesces.

And it’s a doggy dog.

So the bigger the chunk of matter, the more gravity it has, the more rapidly it then accretes.

And it winds out very quickly.

It’s an unstable system.

And then you get the moon.

Earth would look like that.

If we didn’t have weathering, if we didn’t have life, if we didn’t have…

Because the weathering hides the evidence that you’ve been hit.

And so the moon with no atmosphere, you get hit, it’s going to be there a billion years from now.

So that’s why we don’t look like the moon.

That’s interesting.

Yeah.

Good one, right?

So StarTalk fans had their own questions on this very topic.

It means it’s time for Cosmic Queries.

So Paula, you have some moon question for us.

I do.

Renee Douglas from Pittsburgh wants to know what actually defines a moon?

For example, Mars’ moons, Phobos and Deimos, are not round and are captured asteroids.

Yeah, they’re still moons, but they’re pretty lame as far as moons go.

So what is a moon?

It’s a rock that orbits a planet.

A rock that orbits a planet.

That’s a moon.

It could also orbit another, say, asteroid or something like that.

Yeah, asteroids have moons too.

Yeah, so it’s a smaller solid object that’s orbiting another solid object that’s probably not a star.

Yeah, and, but if the object is large enough, then their center of motion sits in space between the two of them, then you might call that a double planet.

But if the object is not so massive that it pulls the center of mass out in space, and it’s deep inside the larger object, then it’s doing most of the motion around.

And so, such is the case with our moon and us, and all the other moons of all the other planets.

Pluto has a moon that’s so big that it does this, and the center of mass is in space, so it’s more like a double object.

You thought I would say double planet, didn’t you?

No.

That’s what I thought.

That’s what I saw coming.

Yeah, no, no, yeah.

Pluto got demoted.

We’re keeping it that way.

I know.

I’m so sad about that.

We aided and abetted that in this institution.

You didn’t care for it to be a planet?

Yeah, we did it first.

If I had known that, I’m not sure I would have come here.

Okay, more moon questions.

I do.

Matt Wolfson on Facebook wants to know, because Matt doesn’t waste time, he wants to know, why does the Earth only have one moon, but Jupiter gets 30, and does the Earth have moon envy?

Chuck?

Well, Jupiter has now, as far as we can tell, way more than 30 moons.

The reason, basically, that Jupiter has so many moons is because it has so much gravity that it can hold on to more moons.

And there’s more material, more objects in the orbit of Jupiter for it to capture.

It had more material to start with to make moons in situ as well.

In situ means at the same time, in the same place.

You don’t have to tell that to me, Charles.

Okay, sorry.

Does the Earth have moon envy?

I don’t know, Neil, should we be envious of the moons?

I’ll tell you why not.

Because we have like the fifth biggest moon in the solar system.

Tim Kardashian?

But we’re the fifth biggest planet in the solar system, so it kind of matches, right?

Okay, Titan I think is a little bigger, and Ganymede is bigger.

Ganymede is bigger.

That might be it.

We’re in the top five moons of the hundreds of moons in the solar system.

So I think we’re, I don’t have moon envy.

We have beautiful eclipses that no other planet has.

Because the moons are so tiny compared to the size of the sun.

Our moon is nice and fat, and it perfectly covers the sun.

We have beautiful eclipses.

I’m rocking our moon.

Up next, Bill Nye the Science Guy takes a trip to the movies when StarTalk returns.

We’d like to acknowledge the following Patreon patrons for supporting StarTalk Radio, Calvin Mitchell and Sinai Coons.

Thanks for helping us make our trek through the cosmos, guys, because without you it would be a lot more difficult.

And if you would like to have your Patreon shoutout, go to patreon.com/startalkradio and support us.

Bringing space and science down to earth.

You’re listening to StarTalk.

We’re featuring my interview with surreal film director Darren Aronofsky.

His blockbuster film, Noah, reimagines the story of the great flood from the Bible.

And I asked about the challenge of creating fiction from a source that some people take literally.

Let’s check it out.

I think the whole fight over did it happen or didn’t happen is really a bad fight to have.

I think the power of those stories is in there that they are stories.

A good example is like Icarus.

You know, we all know he didn’t fly with a pair of wings.

Yet I say the word Icarus, you understand exactly what I’m getting at and what the morals of that story is.

So to have an argument about did the whole world flood or did just the Black Sea get filled in?

Did he actually collect all these animals?

It doesn’t really matter.

The power of that and how it could inspire us and the reason that we should, you know, respect those stories, they’re part of our culture.

They’re part of all of human culture.

They don’t belong to one group.

They belong to everyone.

And out of that literature, we can really learn things about ourselves.

The same way you can read Shakespeare and learn.

The way you can look at the Greek myths, the way you can look at Gilgamesh, the way, you know, you can look at your Mayan myths.

All of them, they’re all part of human culture.

They’re all our stories and they all have that power.

Paula, can a story be truly powerful if it’s not actually true?

I think so.

The first time I tried to stand up, I bombed.

But my best friend lied and said that I was really great.

And so I continued to work and that helped keep me performing.

And that’s how I became, I don’t know if you’d call it successful, but you know, whatever.

So had your friend told you the truth, where would you be today?

I don’t know, but the original story wasn’t true either.

But it was powerful, wasn’t it?

It was very moving.

Any number of people here thought I’ll be a stand up.

So Charles, as a scientist, are you tempted, because I am occasionally, to investigate stories like Noah’s flood to see if it would actually be possible?

Absolutely.

And like say, did Icarus’ wings might have the lift actually to carry him up high?

Yeah, things like that.

They’re always fun to think about.

How much lift do you think he’d need?

He didn’t have enough.

Yeah, clearly.

Yeah, for size.

I mean, his wings would have had to have been like the size of this building.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Do you know how much rain is needed for Noah’s flood?

Did you ever count it?

Yeah, if you go 40 days and 40 nights without stopping, you assume that say a good thunderstorm gives you about an inch per hour.

So you multiply that.

24 times 40.

You get about 80 feet of rain.

OK, and if you imagine 80 feet of rain, that’s enough to sink a lot of buildings back in biblical times.

So that seems reasonable to me.

Now did the rains come down like that?

I don’t know.

You’d have to think a lot harder about the meteorological situation Noah had to back occur.

So I thought a lot about the weight of Thor’s hammer.

Yes.

And, you know, he can lift it, but nobody else can lift it.

And I found a clue in one of the Thor movies about how much it would weigh.

And I did the calculation and it would the density of that hammer is equivalent to cramming a herd of 300 million elephants into a chapstick casing.

Oh, like a neutron star.

Basically a neutron star.

Precisely.

Well, except remember…

But then I was later corrected and they said, no, it weighs 42.3 pounds.

And it’s made of a fictional material.

Uru metal.

He’s good.

He’s good.

And so I had to concede, but I like my answer better.

Your answer is better.

Uru metal supposedly changes its density depending on who picks it up.

You have to be so-called worthy in order to pick it up.

So if you’re not worthy, then all of a sudden it’s like 300 million elephants and chapstick.

I think my vacuum cleaner is made of uru metal.

Because I’m apparently the only one in the house that can lift it.

You are worthy, Paul.

You are worthy.

Paula is worthy.

Well, before we wrap things up tonight, we have a dispatch from my good friend Bill Nye.

I love his dispatches.

And this one is on the science of telling stories through film.

Let’s check it out.

We all love movies, Neil, because we love stories.

We don’t just like the story, though.

We like how the story is being told.

Think of a picture.

If it was created by an artist, we hope it brings out some emotion.

You want to know what the artist is driving at.

But when it comes to a picture or still image, you, the viewer, have to provide the transition from beginning to middle and end.

But with a moving image, a moving picture, the transitions are built in.

It’s always changing with time.

The creator, the artist or director can change locations, change characters, even change events in history in the blink of an eye.

And then with your eye and brain, you merge those moving images together into a seamless story.

No matter how the story is told, though, if it’s a good story, you want to know what happens next.

That’s why I love this part.

See, this is where the ballerina and the black tube.

We all love stories.

One of the first tapestries for stories were constellations of the night sky.

Characters interacting.

No matter where we were in the history of civilization on this planet, there were cultures with stories on the night sky.

And fiction has value whether or not it’s true because there are lessons there to be learned.

There are lessons in Bible stories.

Some people take them literally.

Those people tend to not be scientifically literate.

If they take them metaphorically, there are lessons to be drawn from it.

Fairy tales.

You don’t evaluate fairy tales for whether or not it’s true.

You sit back and say, what did that mean?

What’s the lesson?

And why?

And so when I think of storytelling, I think of the potency of communicating lessons.

Not factual information, not data, but lessons.

And boy, do we as humans need lessons.

And these lessons, if they’re good, they will transcend the moment.

They will transcend time.

They will be passed down through cultures, through the present and into the future.

Because those are the lessons that matter for civilization to survive itself.

So that’s what I think of when I think of stories.

When I look up at night, I imagine that I’d be one of those storytellers to carry knowledge, wisdom and insight from one generation to the next.

And that, for me, is my cosmic perspective.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron