As an appetizer, Anthony tells Neil about some of the most disgusting things he’s ever eaten on his adventures, from African bush meat to rotten, fermented shark, and how a bowl of noodles changed his life. He and Neil discuss the business of food, including a vivid description of “pink slime.” Anthony, a bestselling author whose book Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly changed the course of his life, also gets personal about his self-destructive early years and what saved him. Between courses, comic co-host Eugene Mirman and Marion Nestle, Professor of Nutrition at NYU, dish out a heaping helping of dietary science, evolution, cultural relativism and physiology. Next, we focus more on cooking and eating, from the experimental techniques of molecular cooking to the “Nose to Tail” movement that incorporates respect for the animal into the culinary process. Anthony explains how to avoid getting food-sick in exotic locales and why he’ll never again drink cobra blood out of a snake’s still-beating heart. Marion Nestle tells us how to avoid food-borne illnesses here at home, while Eugene Mirman shares his advice for curing viruses and the common cold. You’ll learn why we can’t eat wood, why eggs get fluffy when we cook them, what altitude does to the human palate, and what type of food the astronauts on the International Space Station desire most.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

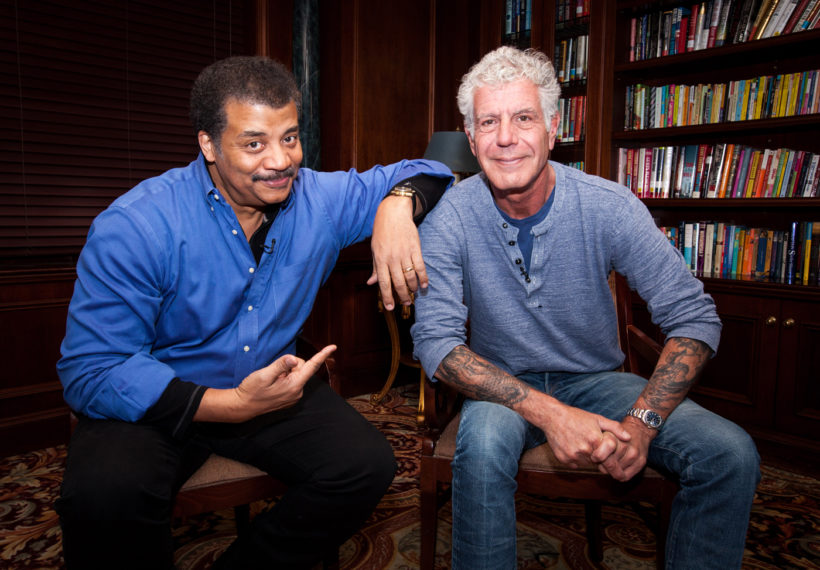

StarTalk Radio first interviewed Anthony Bourdain back in 2013 in a show we called A Seat at the Table with Anthony Bourdain. It was my first time meeting him. And I was just struck at the time and ever since...

StarTalk Radio first interviewed Anthony Bourdain back in 2013 in a show we called A Seat at the Table with Anthony Bourdain.

It was my first time meeting him.

And I was just struck at the time and ever since by his humble beginnings and what they had turned into, what he had made for himself over the years.

Having begun early on as a dishwasher in a restaurant and he speaks candidly about these beginnings, his early drug addictions.

I had not at the time yet read his memoir on this subject, but he was been quite candid about it his whole life.

And to realize that in America, you can overcome such curve balls, you can overcome such obstacles and still make a life for yourself, a brilliant life for yourself, not only for yourself, but for others.

So many people were touched by him, by his personality, by his honesty, his authenticity, that is apparent in every sentence that he utters.

I think what we'll miss most about Anthony Bourdain is how much he reminded us or alerted us for the first time if we never knew, how important food is for bringing us together.

Think about it.

Often the food of another culture is your first encounter with that culture.

Before you even meet a person who represents that food, you eat their food.

You say, oh, this is intriguing.

Oh, this is odd.

I wonder why they did it this way or what accounts for this tradition or this habit.

And Anthony Bourdain wasn't simply a celebrity chef.

He was, yes, he was that, but he was also someone who reminded us how small the world is or how small the world needs to be.

For Anthony Bourdain, your seat at the table wasn't just a place to share food.

It was a place to share culture, a place to experience people and places and things that are different from us, but in a completely unarresting way, in a completely calm and honest and embracing way, no matter how different their food is from your expectations or your desires.

So I present for you StarTalk Radio's 2013 interview with Anthony Bourdain.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk Radio.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

I'm an astrophysicist with the American Museum of Natural History, right here in New York City.

We also serve as the director of the Hayden Planetarium.

And I have with me my co-host for this program, the one and the only Eugene Mirman.

Eugene, welcome back.

Welcome back to me.

We so tap your talents for this.

Thank you.

And this will not be the last.

No.

For sure.

This would be a fun way to fire me.

And you're still on one of the voices in Bob's.

I'm still one of the voices of Bob's Burgers, also not replaced.

Bob's Burgers.

We'll get back to Burgers in a minute.

Today's show, by the way, is about food and nutrition.

So I combed the land.

Then I found someone who actually has the title, Professor of Nutrition at New York University, Marion Nestle.

Marion, welcome to StarTalk.

Glad to be here, I think.

She thinks.

Yeah, so you'll be the judge of that later.

We'll find out.

First, I'm intrigued and impressed that there's such a thing as a professor of nutrition.

So I'm glad that somebody has that.

He thought of it like alchemy.

No, so no, so I'm...

Nutrition departments all over the country.

No, I just never ran into one, and I'm glad you were here and ready for us.

Ready for you.

Because in this episode of StarTalk, we have my interview with Anthony Bourdain.

He's the famous TV...

Travel chef.

Travel chef, in fact, you know, first he had a New York Times best-selling book in the year 2000 titled Kitchen Confidential, Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly, best-selling book.

Which I understand is a very accurate account.

Excellent, excellent.

So he's been around a while, and he had a long-standing travel channel show called, of course, No Reservations, and he's moving from the travel channel to CNN, and he's gonna do a show, Cuisines of the World.

So I just chatted with him about what made him tick, what got him interested in food.

In particular, what intrigues me, and we'll get back to you on this in a minute, is just how cuisine can be so different around the world.

What some people think is nasty, other people think is extraordinary, and how people just eat differently around the world.

So let's go to this first clip right away, and we'll have a lot of time to talk about it and carry it into the other segments.

My opening clip with Anthony Bourdain, chef extraordinaire.

People always say, oh, I've been to this country, and this food is a delicacy there.

That's cute to me that the food tastes nasty, or some bug that they pulled out of the ground and sauteed.

So what's with people saying something is a delicacy?

Well, it's rare or expensive.

You know, it's valued more than, you know, the way we look at the shrimp or lobster or truffles is the good stuff.

A lot of people in this world look at ingredients that many of us would probably have difficulty with.

That's an attitude that changes really quickly the more you travel.

Something I got over very quickly, particularly, you know, you talk about, wow, their food in Thailand is really repulsive to me.

I mean, they eat bugs.

But the Thais who were largely a non-dairy culture, try to put yourself in their shoes.

They're looking at us, eat a cottage cheese, a roquefort would be truly horrifying.

And if you think about it for a second, what that must look like.

Yeah, so you get some milk and then turn it into cheese and then let mold grow on it, then eat it.

Yeah, just hideous.

I got over sort of using words like bizarre a long time ago when looking at how other people eat around the world.

What I do find interesting though is you go from one country to the next and one of the simplest measures of this is what is the assortment of flavors that they infuse in their potato chips that they're selling?

Yeah, for example, right?

I mean, you know, so in Japan they have like fish flavored potato chips.

I mean, we eat fish here, but I don't know that that would sell.

There are whole spectrums of flavors that other countries, other cultures take for granted and require in their diet.

In the Philippines, there's a whole bitter component that we are almost instinctively not happy with.

I mean, they will introduce bile into dishes to give it that welcome bitter note.

Cultures like Scandinavian cultures where there's a very limited spectrum of flavors, not a lot of spices traditionally, a lot of fresh fish, fresh fish, frozen fish, more fresh fish, maybe some preserved fish, as well as South Pacific cultures where it's all sort of sweet, fresh fish, not a lot of salty, savory.

There's a tradition of rotting things, like fermenting fish, getting it really offensively funky by our standards, just because I think out of boredom.

It introduces another flavor.

And it's worth noting also that we, Western societies anyway, used to do that.

Roman times, the condiment of choice was essentially something called garum.

It was essentially rotten fish guts and rotten fish sauce.

This was the salt, the principal seasoning ingredient all across Europe.

So even our own tastes have changed.

For a lot of people, the last frontier is the textural thing.

Particularly in Asia, they like squishy or even rubbery, chewy, or a lot of traditional European cultures have a cartilage texture.

That's something that we really have a problem with.

We tend to like crispy.

Once you cross that border, you're really, you're someplace special.

To get back to you, you're gonna talk about delicacies and value.

A lot of, I think, you gotta ask always, is there an assumed medical component to what we're talking about also?

I think a lot of what we consider the really freakiest foods, the eye popping, what, why would you eat that?

A lot of that has either folk medicine or traditional Chinese medicine applications or a regular feature in my life in China is if something arrives still wriggling or there's a sex organ involved, it's usually accompanied by winking and banging on the bottom of the table.

This will make you strong, you know, many, many sons.

You know, it's like, oh God.

Wow, so Marion, I gotta go straight to you on this.

When we think of nutrition, I think of things that are tasty that might be good for me.

And for so many of the cultures of the world, I don't know that they have an active science of nutrition, but they just simply know what has worked over the centuries, right?

So, is a person more likely to think that something tasty is actually nutritious?

Probably, but the point is that people...

I'm with the physiology.

People eat what's available.

You know, before there were supermarkets and before there was internet food and before there was food on every corner, people had to eat what was available to them.

So they learned to put together a diet that supported life, supported reproduction.

So the empirics of that is, if you died, you didn't keep doing it.

Yeah, they wouldn't be here if it hadn't worked.

So wait, you were saying that people would eat healthy.

You would think ribs were delicious because they're healthy because they're delicious?

If you had them.

If you had them, you'd be like, this must be.

Because these people survive.

These cultures survive.

These populations survive.

So it's self-selecting.

So it's self-selecting.

And we know that healthy diets can be made out of almost anything as long as the foods are varied.

In India, they drink bear-ass friend soup.

Yeah, and you don't eat too much of them.

On that note, we'll come back to StarTalk Radio after this break.

We're back on StarTalk Radio, and I've got Eugene Mirman.

Hello.

And the show is about nutrition.

So, Professor of Nutrition here, Marion Nestle.

Marion, thanks for being on StarTalk.

Coming up from New York University.

And, in fact, you have a book, just was published, Why Calories Count?

From Science to Politics.

How about that?

That's awesome.

Because calories do count.

They do.

So, here we are talking about nutrition all around the world.

And so, here are people eating local foods.

They're not thinking, does it have vitamin C?

Does it have vitamin A?

But if someone gets sick, or the tribe doesn't continue, presumably they figured out that that diet wasn't good.

And so, over the generations, an emergent diet comes that happens to work out.

If it didn't, they wouldn't be here.

They wouldn't be here.

Everyone who tried to just only eat dirt is dead.

That's right.

All the religions and the people who just only just.

All the cults and all the things.

Yeah, they'd like suck on a weird rock and be like, I still feel hungry.

They're all dead.

They're all dead.

All we have now is French food.

A lot of Asian food.

So here in America, I guess since the 1950s, but certainly in recent decades, fast food is a major part of the American diet.

It's everywhere.

And then with the American cultural influence around the world, our fast food restaurants are showing up in other countries.

Is that good?

Is it bad?

I mean, do you have an opinion on this?

It's business.

There's only a certain amount that people can eat.

Americans, they're maxed out on what they can eat.

If these companies want to make money, they have to move it overseas.

So, they can't make us fatter than we are.

Fat max.

And we now need to make everyone in Vietnam fat.

We're working on it.

And then when Earth is done with the next planet, right?

All right, but fast food shouldn't necessarily make a person fat.

Not if they don't eat too much of it.

If they don't eat too much of it.

So, the issue is not the existence of fast food, it's the regulation of the consumption of food.

Yes, and that turns out to be evolutionarily complicated because we have about 100 physiological factors that encourage us to eat more.

And one or two.

Because historically, on the Serengeti, that's survival.

If you found a McDonald's in the Serengeti, you would be like, I'm gonna eat all I can, because the next McDonald's is far away.

Centuries away, possibly.

I had a brother-in-law who grew up in Alaska, and every time we fed him, we said, do you want seconds?

And he said, you never know when you're gonna eat next.

But in fact, he does know when he's gonna eat next, and it's in three hours when it's the next meal.

Right, so we're not very well-tuned to the environment that we're in, and our physiology is much better at saying, eat, eat, eat, eat, you're hungry, better get the glucose to the brain quick, and much, much less effective at telling us when to stop.

When to not eat.

Alas.

We're like geese trying to turn ourselves into foie gras.

Band in California.

So you're saying the ready availability of fast food is what's contributing to our inability to stop eating.

Yeah, the things that encourage people to eat more are having it right there.

If we had candy here, we'd be eating it.

The fact that you could eat it anytime, night or day, 24-7.

Because you've got the refrigerator that's got the food through the night, and there's a corner person selling you food.

Right.

Particularly in the cities.

So that makes people eat more.

You make it sound like gluttonous monsters surrounded by piles of food.

No, we're just encouraged to exercise our physiology.

We're not biologically prepared for the world we've created around ourselves.

Right.

That's right.

You know, I spoke with Anthony Bourdain about this, just to get his reaction to it.

Let's find out what he says.

So what about the idea of what Americans have done to some foods?

We put cheese in a can.

Now, maybe the cheese tastes okay, but that's got to be an abomination to the cheese cultures of the world.

Increasingly, the French are doing it too.

You know, the great cheese making cultures, by joining the EU, have agreed to bastardize a lot of their traditional artisanal products, like cured meats, traditional forms of cheese making.

They've been killing their own products for years.

Is that not our influence, our cultural influence on them?

It's a combination of convenience food culture.

Well, who invented convenience food?

America?

I think it's a byproduct of post-war affluence less time to kick back.

Post-second world war.

Yeah.

More specified for the current generation.

People forget, they lose touch with their roots.

They learn to demand newer, saltier flavors.

So it's not just us, unfortunately.

So there's not only a concept of fast food, to which there's been this resistance, I guess they're calling it slow food, right?

I mean, has that movement caught on?

People certainly talk about or think about where their food's coming from a lot more, and not just at the elite foodie levels.

People, even if they're not particularly knowledgeable about organics or sustainable or local or artisan, all of those very fuzzy words, at least they're thinking about it now.

You only need to look at, like McDonald's has publicly forsworn any use of pink slime.

Pink slime, it is not an ingredient, according to the rules.

It is a process that allowed ground beef manufacturers to essentially buy the outer cuts of beef that would otherwise previously have had to be discarded or used for pet food because they were more likely to come in contact with hides, excrement, other animals and contain E coli.

They found by introducing, as I understand it, an ammonia vapor, basically steaming this stuff, whipping it into a mulch-like paste with bits of extruded fat, mixing it into this slime and processing it with ammonia that they were able to bring the likelihood of E coli down.

Now, it doesn't sound like good stuff for sure.

And there was clearly a backlash, though not a huge one.

The fact that McDonald's and other major retail outlets are saying, we're not using it anymore, it's not like they're nice guys.

They're looking pretty far into the future and seeing that this is going to come back and bite us.

We're saving money now, we're making money now, but this could really come back and hurt our brand.

So clearly that's one of many indications of this sort of thinking affecting the marketplace, you know?

Yeah, so it wasn't, like you said, it was not a separate ingredient because it was still beef.

Well, that's up to you to decide whether the introduction of an ammonia vapor or whatever is an ingredient or a process.

Personally, I would like to know if there's ammonia in my cleaning product, in my meat.

All right, so this is kind of America's hallmark.

I mean, agribusiness, growing production and storage technologies, I think America has led the world in this.

We have.

I looked this up recently.

We're spending a third today of our annual budget on food compared with what we were doing in the 1950s.

Our single largest privately held company is a food producer.

I think Cargill is the biggest American privately held company.

And so we're making more food on less land with fewer farmers than ever before.

No doubt about it, frozen food, surely a good thing, most of these things, but with the good comes the bad.

And the bad might be that it is in the financial interests of some very large, powerful companies that you continue to eat badly and too much.

And they're gonna spend a lot of money, as any company will do, to make you continue to buy their products.

And a lot of these products are not ideal staples of any diet.

We need only look at the way Americans look and the state of our health to see that that's the truth.

So is processed food bad?

I like french fries.

I like burgers.

I had a burger last night.

It's not like cigarettes.

It's a matter of proportion.

It's not you can't eat it.

You can't eat too much of it.

That's hard.

So it is so good and so cheap.

It makes it that much harder to regulate.

And the politics come into how come it's so cheap.

Okay, so what's an example of that?

We subsidize corn and soybeans.

We don't subsidize broccoli.

And soybeans, what do we do with that?

That's so bad for people.

Soy oil, it goes into processed foods.

So what's your solution to this?

Is it to make food more expensive?

Is it to change the availability of it?

What's the solution?

Yeah, you wanna change the environment in order to make it easier for people to eat more healthfully.

That's what Mayor Bloomberg is trying to do with his 16 ounce soda cap.

He's trying to outlaw 20 ounce sodas in the city.

Yeah, he's trying to make fat people illegal, which I think is a good thing.

So are you over that line, are you ready to?

I don't drink a lot of soda.

I'm just a regular fat person.

But I think that band sounds pretty good.

But what if we subsidize parsley?

It's not a band, it's a cap.

Yeah, yeah, it's a cap.

It's a cap.

So if there is a public good that laws can serve, because somebody out there is more concerned about your health than you are.

Yes, because they have to pay for it.

Right.

If something goes wrong.

Right, the insurance base, the tax base.

I mean, there have been estimates, I don't know how good they are, that overweight costs America $190 billion a year.

You can go to Mars twice for that.

I would hope so.

And imagine if the trip was full of people who were overweight.

The savings combined with shipping away the problem, that's a double.

Plus the exploration, it's just like, I'm full of solutions.

So lately, fast food has been fortified in ways, so you are getting vitamins and minerals and things.

Oh, it is vitamins and minerals and protein and other kinds of nutrients.

It's not sodas.

Sodas are the only thing that have calories and no nutrients.

And no nutrients, yeah.

And alcohol, sorry.

You think there's no nutrients.

There's no.

Not even whiskey?

Especially whiskey.

It makes pregnant people run faster?

Isn't that true?

That's true.

When we come back to StarTalk Radio, more with my interview with Anthony Bourdain.

We're talking about nutrition around the world, food around the world.

More on StarTalk Radio when we come back.

Thanks You're listening to a 2013 interview that I conducted with Anthony Bourdain for StarTalk Radio.

This was about when his TV show shifted from the Travel Channel to CNN to become Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown.

That title is a reminder that on his show, you're not only gonna be talking about food, you're gonna be an adventurer and an explorer.

And that's what his successful TV show had become on CNN.

Let's pick up the interview with Anthony Bourdain.

We're back on StarTalk Radio and I'm with Eugene Mermin.

Hello.

And I've got Professor Marion Nestle, spelled like Nestle, I guess, but without the accent.

Without the accent.

Too bad, right?

She's Professor of Nutrition at New York University, thought a lot about this.

And not only nutrition in general, but the role of food and its impact on culture and politics.

In fact, you've got a book out called Why Calories Count?

From Science to Politics.

Excellent title.

Check it out.

So what's interesting is different regions of the world have different diets, and you can look at how long those people live and say, hey, maybe something's going on in their culture that's not going on in my culture.

They've talked about the Mediterranean diet that is high in, I guess, olive oils and things.

There's the Japanese, broadly the Asian diet, which is very low fat, high carbs.

Let's hear what Anthony Bourdain had to say about it, then we come back and get some of the science of why that may or may not be true.

Let's check it out.

Tell me about these diets, we call them diets, whether it's just the mainstay, culinary offerings in various parts of the world.

There's a lot spoken of the Mediterranean diet or the Japanese diet, and they live a long time, heart disease is low.

From your life experience, is all that true?

No doubt about it.

I mean, you go to Crete, for instance.

I guess we know it's true, but...

Look, if you're...

Are we gonna credit the food or because there's no stress or because...

How big a factor is the food?

I'm guessing there's...

You know, you're a Vietnamese rice farmer.

There's...

You're working hard.

You're working...

You are working hard, and there is stress in your life.

Especially if you've been through three or four wars in the last 30 years.

I don't think that's it.

I think clearly the ratio in much of the world, the ratio of...

You know, I'm a confirmed carnivore, but clearly there's something to be said for cultures where the ratio of meat, of protein, to fresh vegetables is completely different.

Ours is distorted.

Much of the cultures we're talking about, they use meat or bone or protein almost as a flavoring ingredient.

Very carefully, much more valued.

You have delicious, for the most part, vegetables, generally a filler like starch, like whether it's rice or cassava or whatever it is.

Clearly, it has an impact on what your body looks like and how long you're going to live.

No doubt about it.

You're over six feet tall.

In Japan, people hardly get that height.

Is it a trade-off between that kind of diet and whether you grow tall?

I don't think it's a trade-off we make anymore because they're getting taller and bigger.

There's no doubt about it.

As they become fonder of Western food and processed food, the same thing is happening there as here, the bulking of the world.

But I think, yeah, there clearly is.

One of my favorite, I'm not particularly well inclined, as much as it might be good to eat more vegetables and less animal protein, I'm not particularly well inclined towards really hardcore unwavering vegans.

One of my favorite statistics is that apparently vegans in non-industrialized cultures seem to do very much better than vegans in industrialized cultures.

And people were trying to figure out why that was, why they're living longer and seem healthier.

Apparently the insect parts and carcasses in rice are much higher in non-industrial cultures.

It's left in the product.

Yeah, so basically they're getting a lot more animal protein.

Insect protein.

We're flicking away the insects out of our vegetables.

Very high in protein bugs, by the way.

People eat those for a reason.

So, you know, I happen to know separately that little people live longer than big people.

So if you have a culture where everyone's little, then maybe it doesn't matter what they eat.

Leave them alone.

That's why babies live forever.

So in certain cultures, people are just smaller.

Maybe that's the biggest driver for their longevity.

Or is there much truth in these diets that...

The statistics all show that there are plenty of countries in the world that have much better longevity than we do.

And they tend to have in common that they eat more plant foods, fruits and vegetables and grains, and they don't eat as much meat, and they don't eat as much junk food.

And as the American fast food and soda companies...

It's not just fewer calories.

It's the actual mixture of...

It has a lot to do with calories.

It's just harder to eat so much parsley that it's as many calories as a burden.

It's really hard to get fat on parsley.

You have to eat roomfuls of it.

It's really tough.

Now, Buddha, last I checked, was a vegetarian, and he's generally shown as quite chubby.

Yes, but everybody was bringing him rice offerings all day long.

He had a very high-carb diet.

All day long.

Okay, so you're prepared to say that in America, if we want to live longer, cut the meat.

Cut the calories.

Oh, cut the calories.

Cut the calories and change the balance of the meat.

And change the balance.

Eat more fruits and vegetables.

Don't eat so much junk food.

Balance calories and love what you're eating.

What does that do for you?

That's my advice.

Love what you're eating.

Eat.

Find ways to make foods that aren't burgers delicious.

Yeah, or just make sure that you enjoy what you eat.

Burgers is the reference frame for all of the fruits.

Burgers are totally fine.

Food is one of life's greatest pleasures.

You should enjoy it and not make it your enemy.

It should be your friend.

Right?

Befriend food.

You're like Yoda.

You're like befriend food.

Eat it.

When we come back, more of my clips with Anthony Bourdain and my in-studio guest, Marion Nestle and of course, Eugene Boris.

Be right back.

We're back, StarTalk Radio.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your host.

Find us on the web at startalkradio.net.

You can download our archives of shows, great stuff there.

And not only that, we're on Facebook, like us there.

Just StarTalk Radio, you'll find us.

And we tweet, StarTalk Radio, of course.

Eugene, you tweet.

Yes.

At EugeneMirman.

M-I-R-M-I-N.

M-I-N.

And my special guest today, right on-

I tweet.

You tweet?

I do.

A tweeting nutritionist.

Marion Nestle.

Marion Nestle.

Oh, we came out of that previous segment, I called you Nestle, I'm sorry.

I can't be the first one.

No relation, you're not the first.

And I'm not the first.

And you won't be the last.

And I surely won't be the last.

By the way, we're also on the Nerdist channel of YouTube.

Check us out in video form.

So we're featuring my interview with Anthony Bourdain.

Yeah.

He gets around, he makes great food, he eats food that is prepared all around the world, and an intriguing subject, as you know, because not everyone eats the same way.

My great disappointment traveling America is the same restaurants are in the same places.

And I asked him about food that's sort of good or bad.

You know, I mean, you can make that judgment, I suppose.

You mean, like, morally?

Because he travels the world.

I mean, when you travel, you eat different foods.

Yeah, yeah.

So I asked him, what kind of good food did he have?

What kind of bad food?

No, just what didn't taste good.

Yeah, yeah.

Taste of good didn't taste good, that's all.

But might be a delicacy in its land.

So let's find out what he said.

The fermented fish in Iceland is something I will never, ever be able to really, even many people in Iceland, probably even the majority, it's a celebrated national dish that they eat on their holidays, and it's basically rotten sharp.

I'm not gonna be visiting that again.

I could choke down anything to be a good guest.

Really, the only real problems are, when it's a matter of freshness, you know, when it's a really poor culture with very limited access to ingredients.

You have a hearty digestive system?

Yeah, but I mean, the two times that I've been brought down and lost a day's work were both tribal situations, the whole tribe looking at me, it's bush meat, it's whatever protein they could scrounge, it's not in good shape, there are cleanliness issues.

You took one for the team.

I absolutely did.

The surprises are everywhere.

Eating street food in Asia changed my life.

It ruined my life in wonderful ways.

When you've had a really well-made bowl of spicy noodles in Vietnam, even out of a chipped bowl on a low plastic stool in the street, your old breakfasts just won't cut it anymore.

You cannot go back to be the person you were before when you've experienced some of the degree of spice, complexity, and even a little bit of pain.

There's this element of sadomasochism in some of that food that kind of disturbing and yet enticing.

Good and bad food around the world.

I mean, this was parodied in or captured in the Indiana Jones second of those.

Where he has to eat the little boy's heart.

I can't remember what that was.

That's when they pull the heart out.

They give him the Icelandic shark that's...

He killed monkey brain and eyeball soup.

And so are these real foods out there?

They must be.

It's whatever they're, if they're being served, they're obviously real foods.

Unless they're trying to get you.

Do they do that?

When you go somewhere, they're like, we eat brains all the time.

So is there study on the nutritional analysis of all these exotic foods?

Absolutely.

And what do you guys find?

I mean, I guess they have nutrients.

All foods have nutrients.

At the end of the day, they're just eating something that was once alive.

That's right.

How good are sweet breads for you, would you say?

I think in small quantities, I wouldn't worry about them at all.

No, but.

It's neither sweet nor bread.

Sure.

It's organ meat.

Yeah.

Of mammals.

But if a tiny bit of it will make you strong and fast and outrun people drinking red wine.

Wouldn't you love that?

I'm just trying to have you go like, most people don't know this, but eating butter in the morning is very good for you.

Because they've got their safe of secrets down in the.

Oh, because I'm one of these people who thinks it's okay to eat whatever you like as long as you vary it and don't eat too much of it.

All right, so foods that are really horrendous.

Do you think there's something, it must be cultural.

I mean, a learned taste buds.

Yeah, I mean, if everybody, if you grew up on eating sweetbreads all the time, you would think it was a great delicacy.

If you grew up on eating crickets all the time, you would think it was a great delicacy.

You'd be right about sweetbreads, but wrong about crickets.

There you are.

That's cultural relativism.

Just to give a world blanket statement.

Whether or not Americans are the right answer to this question, hold it aside.

What country in the world has the worst health?

The worst health?

Yes.

Excluding America?

Yes.

Oh, I would say the countries that are poorest.

So, poorest.

Poorest countries.

So, poorest and then the fattest.

Yeah, that.

Good, go poorest, poorest, fattest.

That too.

And then just like vegetarian Asians.

And what's happening in the developing countries now is that as everybody gets a little money, they start eating more.

They just, but then they just eat, start eating like Kit Kats and stuff.

And they start eating like we do, and they put on weight and develop type two diabetes, and there it goes.

It even has a name, it's called the nutrition transition.

Nutrition transition.

Where it goes from hungry to diabetes.

To diabetes, in one fell swoop.

When we come back, StarTalk Radio, we're talking about nutrition, my clips with Anthony Bourdain.

We'll see you in a moment.

We're back on StarTalk Radio.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

I got Eugene Mirman and Professor of Nutrition, Marion Nestle.

The verb, not the chocolate.

Oh, okay, Nestle, that would be.

Is that what it says on your card?

The verb, not the chocolate.

The verb, not the chocolate.

We've been featuring my interview with Anthony Bourdain, the TV chef and world traveler, tasting exotic foods.

And just interesting to hear how he got to where he is.

He's got a story, he's got a story, and the story surprised me entirely.

I had no idea this was in his, I guess I could have done my homework, but I wanted it all to be fresh.

It surprised you because you didn't Google it.

No, but it was all very fresh, and it was a delightful success story.

Let's check out what he tells us.

Well, was there angry, embittered, spoiled?

I was a bad kid.

Where did you grow up?

Grew up in New Jersey in the suburbs, grew up across the river.

What exit?

I was just very disappointed with the way that the 60s turned out, and I was a bitter, self-destructive, drug-seeking kid who really had a hard time finding anything to believe in, and I found a home, the way that a lot of people find a home in the military, I found a home in the restaurant business.

I mean, this was a world of absolutes that I responded to.

I liked the science of, to me, it was a revelation working as a dishwasher.

Why?

Because plates went in dirty and they came out clean every time.

And if I did my job of washing dishes, I got the respect of hardworking people in the kitchen, and that made me feel proud of myself in a way I never had before.

I'll tell you, really-

That was transitional.

Transitional.

I went from a very unhappy, self-destructive college kid, a college dropout to a guy with a-

You liked to transform washing dishes.

Yes, absolutely.

And I lived by those, the lessons I learned as a dishwasher were the most important in my life.

Show up on time.

Sounds like a book.

Have the-

Lessons I learned washing dishes.

I've written that book.

And then, at age 44, I found myself standing, broke but reasonably happy next to a deep fryer at a restaurant in New York.

And I'd written an obnoxious, over-testosterone account of my life that I didn't think anyone would buy.

And suddenly, I found myself on the bestseller list and my life literally changed in the space of a week from a guy who never thought he'd see Saigon, much less Rome, to somebody who's now been traveling for the last 10 years anywhere I want to go in the world doing pretty much whatever I please.

So, not to over-interpret what you just shared with me, but the fact that your life transformed at age 44, that's extraordinary.

Look at how many people give up long before then, saying, look, I'll never make anything in my life.

I'd never had health insurance.

I'd never owned a car.

I'd never owned a home.

I'd never paid my rent on time.

I owed the IRS 10 years in back taxes.

I went to sleep every night hyperventilating from fear for who's gonna call first, the landlord credit card company or the IRS.

I had no hope of ever changing that situation, and that was good by previous year's standards.

So it came as a big, big, big surprise to me to suddenly have the freedom to see this world and do the things that I'm able to do with the people I do it with.

I think it makes me grateful in a way that I might not be had it happened earlier.

So who would have thought food can change somebody's life that way?

I mean, it's an extraordinary story.

Yeah, I was a dishwasher for like a year, but I didn't realize I could do this.

I had six years before I'm his age and have to have accomplished the same stuff.

Gotta keep at it, keep working at it.

You have to work on the dish washing a little more carefully.

I learned a lot, but not quite as much.

So Marion, I think most people who care about their health have either only a pseudo-scientific understanding of nutrition or no understanding at all.

So you've gotta be disappointed with-

Present company excluded.

You gotta be disappointed with the state of knowledge out there.

No, I'm disappointed with the state of science and knowledge in general.

In general, oh yeah, yeah.

It's just one aspect of it all.

Well, it's an aspect that hits people personally.

We put food in our bodies, and that makes it extremely personal.

And it's some combination of protein, carbohydrates, fat.

Yeah, I mean, nutrition's complicated.

There are probably 50 different components in food that we need in order to survive, and it's hard to keep track of them, and you don't know what's in food.

Can I live off of any one of them, if I want to just go all protein?

No, no, no, no, no, variety, variety.

You couldn't live off of just diet coke?

It would be very difficult.

For how long do you think if you just drank diet coke would you live, like, two months, a year?

Actually, it's probably very close to 70 days.

70 days of just diet coke.

Yeah, if you...

Well, it has no calorie sources.

It has no calories and no nutrients, so it's just like water.

So you'd also have to eat bugs.

So it's the equivalent of water, and there have been studies, the Irish hunger strikers, for example, they were very carefully studied, and on average, they lived about 70 days once they decided not to eat anymore.

Okay, so the diet coke experiment, proxied with water, would do that.

Yeah, and if they ate something, then they would have lived longer.

Right, right, right.

We gotta wrap up this hour.

It's been an awesome conversation about food and diet.

You've been listening to StarTalk Radio, and I've had Eugene Mirman.

You've seen him and heard him before.

And of course, Professor Marion Nestle.

Thanks for being on StarTalk Radio.

Oh my gosh, and contributing to the information surrounding my interview with Anthony Bourdain.

You've been listening to a 2013 interview that I conducted with Anthony Bourdain for StarTalk Radio.

And what a kind, sincere, authentic man he was.

It's clear.

Just listen to this conversation and you'll know.

He doesn't hide anything.

He's not ashamed of anything.

He is candid about his mistakes, about his achievements.

And how many of us can really claim that?

We'll miss him dearly.

Let's get back to the interview with Anthony Bourdain.

Welcome to StarTalk Radio.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

I'm an astrophysicist with the American Museum of Natural History right here in New York City, where I also serve as director of the Hayden Planetarium.

And I've got with me, you've seen him before, you've heard him before, Eugene Mirman.

Eugene, thanks.

You've invited us to your Eugene Mirman Comedy Festival, which is a great thing you got going over there in Brooklyn.

Thanks for having us be a part of that.

Thanks for being with us.

And just recently we did a show with you and our name was on the poster.

That was great.

Yeah.

They've been on a poster before.

Well, welcome to posters.

Very cool.

I'm gonna make you a star, Neil.

So this show is about nutrition and we're featuring my interview with Anthony Bourdain.

You might have seen him with his television show on the Travel Channel.

He's gonna have a TV show that's, in fact, he's gonna move to CNN and do a food show.

It'll be like Anderson Cooper in the middle of a food disaster, picking up food going, why?

And I said I couldn't do this just with Eugene, although Eugene is a bit of a food expert because you're a voice on Bob's Burgers.

Yes.

So he's got some food expertise.

And I got a D in chemistry, so I bring that also to the table.

And he eats.

But I had to bring in a little more expertise.

Just, no offense here.

Not offended.

Down the street, we've got New York University, a great institution, one of the jewels in the crown of New York.

And we have Professor Marion Nestle, Professor of Nutrition.

Thanks for joining us on StarTalk Radio.

Thank you.

So Anthony Bourdain, you certainly know the guy, and you've heard of him.

Yeah, yeah, and so we've got a clip of my interview with him, filmed previously, but we talked about just being in the kitchen as a place to experiment, what kind of gadgets are available.

When we come back, I wanna talk about sort of food science and the science of the kitchen and what that means to you.

Let's check out my first interview clip with Anthony Bourdain.

What do you think of all the gadgets that help people cook food?

They make great infomercials.

In almost every case, they're completely worthless.

The salad shooter.

Do you really, you know, the ultimate salad delivery system.

I mean, is cutting lettuce so hard, you know, something that will cut onions for you is completely insane as far as I'm concerned.

There is no better, two good knives, a serrated knife for bread and maybe tomatoes and a good quality chef's knife is all you need and a cutting board, a couple of good heavyweight pans and there's very little that you can't do.

How do you distinguish between tricks and I don't mean it in a circus sense, but just secrets versus 10 years of doing it?

Chris, you serve a food to someone to say, what's your secret?

As though you can just tell that to them and then tomorrow they can do exactly what you made.

There are no-

At what point do you say, look, I've been at this my whole life.

There are no secrets.

This is the secret of the restaurant business and professional cooking is there are no secrets.

It is a mentoring business.

Chefs spend their whole lives learning stuff and then because of the nature of the business, every few months teach everything they know, invest time they don't have in teaching somebody everything they know so that they can maybe have a Sunday off and that they can count on a crew.

It's a military hierarchy.

There are no secrets.

There are no secret recipes.

There are no secret techniques.

Everything that you learn in the kitchen, you were either told open source by your immediate superior and that's been shared with everybody in the kitchen or you have learned it over time painfully.

The ability to tell when a steak is cooked by listening to it in the pan or on the grill or determining that a piece of fish is probably ready to come out of the pan just from the sound of it.

These are things you learn through repetition and that is the great secret.

It's that this is how professionals learn.

This is how home cooks should learn.

People shouldn't be intimidated by recipes.

They should understand that professionals learn through getting it wrong, getting it wrong, getting it wrong, getting it wrong, starting to get it right, eventually getting it right until it became second nature.

It's repetition, repetition, repetition.

You learn all of these things even if you don't understand the science behind why your stew is transforming, why it's becoming thick as it cooks longer, why your egg scrambles, why the steak gets dark on the outside when you expose it to heat.

You may have no understanding of the science behind that, but you instinctively, of course, through repetition, understand it, you learn to use it, and you count on it.

Now, you've used two words in our conversation as fluently as any scientist that I know.

First, E coli just rolled off your tongue.

And tectonic shift rolled off your tongue.

So, what is your science background?

High school science, high school science, but...

But you liked it, I guess.

I did, but people talk about things in the kitchens, like what's happening?

Why is my steak getting brown?

The caramelization of protein, the Maillard reaction.

That's kind of cool to know.

It helps you out.

I'm betting you didn't learn caramelization of sugars in high school chemistry.

No, you learned it real quick.

First time you stick your finger in some, you learn it on a cellular level.

How come that's hotter than water?

I hadn't counted on that.

It's way hot.

So that interview, I just became so enchanted by him.

I felt like I've known him my whole life during that interview.

So we're back in the kitchen.

You like the kitchen.

I love the kitchen.

It's the one place you can do legitimate science experiments and no one will fault you for it.

Absolutely.

And if you're really a good cook, you keep notes on what you're doing.

A lab book.

If Iran tried to build a nuclear weapon in a kitchen, no one would be so upset.

So if your cake fails, you try it another way.

So I'd be curious if on her shelf of cookbooks, she's got lab books of what failed cooking experiments, successful ones.

So is there some experiment you remember most that you discovered yourself?

Well, it's just anything that you make.

You just keep making it until it works.

I think it's interesting that if you cook protein, it sort of changes.

Yeah.

What was he saying when you would burn your finger if you touched sort of...

Did you need him to tell you that you'd burn your finger if you touched...

No, but he said faster than water.

Oh, yeah, yeah.

Oh, sorry.

I don't know science, astrophysicists.

Oh, sorry.

Yeah, if you melt sugar and it's liquefied, it's at a higher temperature than boiling water.

And it sticks to your finger.

Yeah, yeah.

And if you look at chefs, you look at their arms and they've got blisters and cuts all over them.

Yeah, yeah, because they've been fighting food for years in a hot kitchen.

So, yeah, so like for example, egg goes from liquid to this fluffy form because you're heating the proteins.

I mean, it's an interesting sort of consequence of it.

Cream whips.

Cream whips.

Because you're beating air into it.

Right, right, right.

I mean, I love it.

I love it.

When we come back, more of my clips with Anthony Bourdain and I've got Eugene Mirman and the good professor of nutrition, Marion Nestle.

See you in a moment.

StarTalk Radio, we're back.

Find us on the web at startalkradio.net.

You can listen to us three ways.

You can download the podcast on iTunes and our website.

You can find us in the airwaves, StarTalk Radio Radio.

Also, we are on the Nerdist channel under YouTube.

Check us out, you'll see us in video form.

I've got Eugene Mirman, Eugene, thanks.

Sure.

Thanks, and the good professor.

Thanks for agreeing to help out on this interview.

I interviewed Anthony Bourdain and I didn't know very little about him and I got so.

Yeah, did you ever watch his show?

I did, you know, we used Channel Surf and all the food folks.

He's wonderful.

Yeah, it's great to learn about.

And he's got a new show on CNN where he travels the world and he gets paid for that.

Yes, I think most of the people on CNN are given money and exchange for their skills.

It's just to travel around eating things.

Eating things, and he's just actually pretty slender, so he's watching what he eats.

So, in my next clip with him, we talk about the Molecular Food Movement, something I was unsure what that meant, but it's all the rage, and let's find out where that takes us.

I'm reading recently about the Molecular Food Movement, where if you have enough power over molecules, just create the food from a molecular kitchen.

What do you think of that term?

Well, I think it's an unfortunate term.

It's treating ingredients in new ways.

It's manipulating pre-existing ingredients into unusual forms.

And I guess the father of this movement was a guy named Ferran Adria, a great chef, a great restaurant, one of the most enjoyable meals I've ever had in my life.

Where?

Called El Bulli in Spain.

50 cooks cooking for 50 diners.

Never made a profit, considered by many to be the best restaurant in the world.

What Ferran explained, what he did like this.

He said, he's asking a basic question.

Here's a truffle in this hand.

Here's a perfectly ripe peach.

The truffle's $1,500, the peach is a dollar.

Which is better?

Which is better?

This is rarer, it costs more money, but is it more delicious than a perfectly ripe peach in season or a pear?

So he started to ask, what if I treat the pear like the truffle?

I do everything I can that experimentation and science says.

If I trick you when you think you're eating a truffle, if I serve it in a way that you were forced to value it, that draws the eye, that changed the texture, what can I do to this, to change its value, its perceived value, to surprise you, to take you someplace you haven't been before, but then bring you ultimately back to something that at the end of the day tastes like a delicious, delicious pear.

So yeah, they use a lot of natural, mostly natural ingredients like agar-agar, the stabilizers, various processes to either intensify flavor, to trick the mind into, eating a strawberry that doesn't look like a strawberry or an apple that looks like and feels like caviar in the mouth.

That could be fun and exciting in the hands of somebody as talented as Ferran and it could be a long, miserable night in the hands of somebody who read about him and thought it was a cool idea and started doing ghastly and terrible things to food, sheerly to dazzle.

Well, yeah, why is that different from, I go to the cheap deli and they've got the crab salad but it's fish made to look like crab?

Ferran would agree with you, absolutely.

There is nothing different.

It's a technique and a process just like making ham.

A leg of pork is a good thing but as it turns out, if you pack it in salt and then hang it and age it and smoke it, it becomes even more delicious.

So it's basically taking that same engine, whether we're talking a sea leg as it's called, that fake crab, or the making of ham to an extreme degree.

Okay, but at least that's still using natural ingredients or ingredients available to them.

It's not really coming out of the chemistry lab.

This is not chemistry lab.

So this molecular movement is not the bad name.

It is modernist cooking that understands and refined and they spend a lot of time in workshops or laboratories figuring out why does an egg scramble?

What process is happening already when you agitate and beat proteins?

Yeah, proteins get all...

Right, so how can we play with that process?

So we're not talking about introducing chemicals.

In almost every case, most of the stabilizers or things like these were extracts of or natural ingredients that are used elsewhere in other cultures.

So it's not chemistry class, but it certainly does look like a laboratory.

One of his more famous dishes is the spherified olive, which is essentially the extract of the best olives turned into juice and then dropped into a solution treated with a substance, a natural substance, which causes it to basically spherify into a liquid sphere contained only by itself.

So you pick up something very delicately that looks like an olive and it explodes into liquid.

It's thrilling and delicious.

So it's like the essence of olive turned into a bigger olive.

Just as delicious as the original olive, but with excitement, surprise, wonder, and you know, 50 courses of this, it's really like taking off to the moon.

You look stunned by this description of the essence of olive turned into an olive.

I've had one actually.

You've had one and what is it?

It's like having a mouthful of olive oil.

Good olive oil, mind you, but still olive oil.

Like best ever olive oil.

But little, but not as thick or as thick?

Yeah, pretty much, just tasted like olive oil.

If you take the essence of an olive, that's oil, right?

That's what olive presses do.

Well, I'll go home and drink some olive oil and be like, that, but I'll imagine...

And you'll save yourself a great deal of money.

So are these chefs gone awry?

Is this like...

Oh, I think they're having fun.

It's boys with chemistry sets.

They're not murdering people.

Yeah, it's chemistry sets.

They get to play with all this really cool equipment.

They get to play with liquid nitrogen.

What could be more fun than this?

I want a liquid nitrogen nozzle in my kitchen.

See, there you go.

I've always wanted that.

I think you probably could have one, right?

I could probably rig that, actually, now that you mention it.

So if you had that.

Liquid nitrogen is very cool.

It's nitrogen like in the air, in case you didn't know, 78% of the air you breathe is nitrogen.

If you cool it enough, it will liquefy, but now it's like raging boiling because it boils.

And very cold.

Yeah, it's boiling at a very cold temperature.

What would happen if you sprayed it on a fish?

You would instantly freeze the fish.

And then you microwave it, would it be delicious?

Freeze it, then microwave it, then you have a mushy fish, all right?

Just trying to see how well you know science.

Yeah, yeah.

So, no, I've never tried that, but I think that's what would happen if you did this.

So, maybe there are things that a chef could still do to food that these boys with toys haven't yet devised.

Well, they're working on it.

They're working on it.

And there are lots of them working on it.

So, but wouldn't it help if they knew the chemical properties of fat versus protein versus carbohydrates?

And they're working on it.

Some of them might.

I don't know why you're assuming they know.

Well, I'm asking you.

What, in your experience, do chefs have the kind of...

Some do, some don't.

Do chefs have the nutrition knowledge that you have?

I mean, you're an expert, of course, but do they have your threshold of knowledge that you think everyone should have?

I don't think so.

They have knowledge about cooking.

That's what they're doing.

And they're trying to take what little science they know and apply it.

Would they be a better chef if they knew more of what you knew?

Possibly.

Possibly not.

Because so much of cooking is about taste and flavor and getting a feel for how you deal with the ingredients.

Do you concern yourself much with taste?

Absolutely.

Yeah, she seems to be.

Absolutely.

You think people should eat moderately different things.

Of things that are delicious.

Yeah, so that they enjoy it.

She's not trying to get everyone to eat weird, like, paste that is neutral of calories.

I think healthy food should be absolutely delicious.

That's how you'll convince people.

Okay, but the stereotype is that the healthy food is nasty and you're like taking your medicine.

I don't think that is anymore, actually.

I think that's changed.

Well, it should change.

It says the man who's a voice in Bob's Burgers.

It is, at this moment, I'm invoking it as an argument.

Go.

My idea of a really great chef is somebody who can make vegetables absolutely delicious, so that's all you wanna eat.

Ooh, that's an interesting chef's challenge.

Take a meat eater and have him fall in love with vegetables.

Many chefs can rise to that challenge without any trouble at all.

It's true.

Just go to Blue Hill.

Blue Hill is not a bad place to start.

Okay, so you know about Blue Hill.

Oh my God, I've had carrots.

They start out with little tiny spiked carrots and radishes.

Remind me, Blue Hill has their own farm or something, is that right?

It's really delicious.

They control all their own vegetable products, if I remember that correctly.

Just because I'm on a cartoon with the word burger doesn't mean I eat only burgers.

Okay, I'm just, I didn't mean it like offend.

I'm curious about something.

When people eat, different foods react to their systems differently.

You know, some people get indigestion.

I mean, you study the chemistry of people's reactions to food?

Well, one of the things that's really fabulous about the human digestive system is that it can take anything and turn it into calories and nutrients.

Oh, okay.

Really anything, and if there's some people who are sensitive to certain foods and have food allergies and other kinds of problems, but most people just...

Even tofu?

Even tofu.

Just making sure, I'm just curious.

Most people can take anything that used to be alive and that's edible and turn it into...

We're a calorie factory.

We're a calorie factory.

Wood?

Wood would be hard.

That's not suggestible.

I want to talk about eating wood in a minute.

For that, you need termites.

Exactly.

When we come back to Star Talk Radio More on our show on nutrition, we'll be right back.

We're back on StarTalk Radio.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, I got Eugene Mirman and Professor Nestle, Nestle.

The verb or the net?

The verb, excuse me, to Nestle, yes.

We're talking about nutrition, we're featuring my interview with Anthony Bourdain, and we were coming out talking about, could you eat wood?

Now, of course, termites eat wood, and they're having a field day doing so, because they have the digestive enzymes that can get calories out of wood.

They have bacteria in their intestines that allow them to do that.

We have bacteria in our intestines that can handle food fiber, but I don't think it handles wood very well.

Oh, okay.

But actually, it doesn't digest the fiber, it just passes it through, right?

It digests some of the fiber.

The bacteria can digest some of the fiber and turn it into little volatile fatty acids that get absorbed, et cetera, et cetera.

Okay, so we can eat, so lettuce, we can eat but not oak leaves.

It would be difficult.

It would be difficult.

Would it be poisonous or just unpleasant?

I don't know whether oak leaves are poisonous or not.

I'll tell you in a few days.

Why don't you do that experiment and be sure and take notes?

No, but think about a future.

If there's a food shortage in the world and we managed a way to eat something first that allowed you to digest wood, because wood has calories in it, it's got energy, that's why you can burn it in a fireplace.

It's just not available to the human body as an energy source.

So we can imagine a day where you can digest wood.

And what would we do with all the jokes about food tasting like wood chips?

We would have to swap them out for another object or plant.

Some food that tastes like wood not on purpose.

Tastes like sawdust.

Yes, but it's still wood.

In my interview with Anthony Bourdain, I talked about sort of the animal aspect of eating meat.

I mean, if you can eat meat, it's a dead animal.

Okay, are you, are people...

Agreed.

Agreed, okay.

Go on, Neil.

It's not a debatable topic.

But what does it mean to eat something that's been completely, where its origin is completely concealed from you?

It's just a burger, it's just a...

Oh, I see, not like a farm to table kind of thing, but more of like just like buying a big pile of meat or finding it on the ground.

Why?

Would you go out and kill the animal if you knew that's what you were about to eat?

Let's find out what our conversation says.

I'll punch an animal out and murder it with my fist.

Maybe it's more true in America than in other places, but particularly in the carnivorous realm, we shield ourselves from the animal itself.

We buy a chicken, you don't see the feet.

You don't see the head.

It's just packaged and it's just a piece of meat.

Is that a good thing?

No, it's a terrible thing.

But why?

Why do you even care?

Okay, for a whole lot of reasons.

It's always good to know where your food came from.

It's only fair and just.

My friend, Fergus Henderson, was a pioneer of what's called the nose-to-tail movement.

He says, it's only polite, you know, if you're going to kill an animal, or more often have an animal killed for your restaurant or your kitchen, it's only polite to eat as much of it as possible, to not waste.

People should understand where their food comes from, how it was raised, what the impact might be on society as a whole in that process.

But I think also just as sentient, caring people, a decent person would prefer that their animal is raised reasonably happy and killed with a minimum of cruelty.

But if before everyone ordered their cowboy steak, if they said go outside, find the cow that you want us to slaughter, look it in the eye and pull this trigger and shoot it.

Honestly, I think that's an experience.

The more people who can do...

Cow with big eyelashes, you know.

It is something I've done.

When you travel this world, you meet your dinner frequently.

It's difficult.

When you've killed your first pig, you really start to abhor waste, disrespect to the ingredient.

I'm a lot more careful about how I cook my pork now.

You know, I understand.

Something died for that pork chop, okay?

I think you become a better citizen of the world and a more rounded person when you have seen that process and you've made some personal decisions as part of that.

But it is a life-changing thing and I think everyone should take part in it.

I think that's deep.

Do you agree?

Absolutely.

It's philosophically enriched outlook on the food that you confront.

Many people don't eat meat because they can't bear the idea of either raising animals for food or killing animals for food.

People who do eat meat, if they're thoughtful at all, have to come to terms with what that means.

And his coming to terms, obviously, is he wants to respect.

It has a lot of respect in it.

I think that's a philosophical position that a lot of meat eaters have these days.

I want my meat raised humanely.

I know I'm going to be killing it, but I want it at least raised humanely.

My one little part of that, that I do for myself when I'm eating a shrimp, I eat the shrimp with the shell.

I think the shrimp gave its life.

I'm going to eat its shell as well.

Plus, it's chewable anyway.

It's not like a lobster shell, but also.

I eat the lobster shell because I'm a little better than you.

But also, when I cook a lobster, you know what I do?

I remove the claw rubber bands before I put it in the.

Oh yeah, doesn't everyone do that?

No, I don't think so.

You would boil rubber bands with your food?

No, I want the lobster to have one last chance to bite me before it goes in.

Right, it's just, it's just a, it's a.

I guess I selfishly do the same thing because I don't want to boil a bunch of rubber bands.

So it's good that we're both good people, but me more selfishly.

When we come back more about eating animals and some of them even carry diseases, when we come back to StarTalk Radio.

Bye We are back, StarTalk Radio, Neil Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist.

I've got Eugene Mirman, comedian extraordinaire, love your stuff, Eugene, thank you.

And Professor Marion Nestle, recently authored a book, this-

Why Calories Count.

Why Calories Count, From Science to Politics.

Awesome, and it's not your first book.

It's not your first rodeo.

You've been writing about this stuff for a while, so thanks for being on.

We're talking about nutrition, we're talking about food, talking about cooking, and in this segment, we're talking about slaughtering animals, some of which might have some disease that you want to avoid, and it includes interview clips that I conducted with Anthony Bourdain.

Let's get right to, at the top of this segment, my interview with Anthony Bourdain, where we just come out of talking about slaughtering animals, facing them in the eye, if you really want to appreciate what you're eating, and the fact that animals are a source of disease in the world.

Let's find out.

Some pathogens in our culture are directly traceable to viruses that hopped from animals that we either farm or eat or, how does that, does that scare you sometimes?

I'm thinking of avian flu or mad cow disease, or even AIDS with contact with the rest of the apes.

You know, I think exercising reasonable caution, the same way you would if you travel around rural America, is a useful thing to do wherever you go.

I mean, the days when I would eat as far out of my comfort zone as a daredevil, just so that I could tell friends that I drank live cobra blood, I don't do that anymore.

I guess I would advise people against.

I generally-

You used to do that.

Early on, I was so grateful to be traveling.

I didn't think this whole TV thing would last.

I'd never been anywhere.

So yeah, when I was in Vietnam, I made sure to get the live, still-beating cobra heart and drink its blood.

Just so I figured when it all ended, six months later, at least I'd get a free beer telling that story, you know?

Long ago, changed the way I travel to be much more interested in the typical everyday thing.

I think if you use the same philosophy, people always ask me, do you get sick?

Just stomach problems, traveling around, eating all that street food.

Always ask yourself, is this how your average person eats?

You know, is the place busy?

It's generally not gonna be a concern.

If you're aware that avian flu has become a concern in the area, yeah, undercooked poultry is probably not gonna be a good idea.

You will have to think about those things.

If there's mad cow around, maybe, you know, calves' brains at a dodgy pub would not be your first option.

I think if you familiarize yourself with what's going on, as any cautious traveler should, and don't take unreasonable risks, you know, eating brains or spine in a mad cow area would be a bad idea.

They're just using common sense.

Yeah, just like they're not drinking the water in Russia from the top.

You shouldn't either.

Do as the natives do.

So Marion, how much attention do you give in your profession to not only nutrition of food, but the hazards that the eating of food can bring you when they're contaminated?

Oh, I actually have a book.

It's called Safe Food, the Politics of Food Safety.

Practicing safe food.

That, safe food, exactly.

You know, there's E coli, botulism, FA.

Yeah, the Centers for Disease Control says 48,000 people in America get sick with food poisoning every year, and there's 125,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths.

Those are the standard figures.

So what do you do to avoid this?

I try to, when I'm traveling, I try to eat food that's been cooked.

Cook the food.

Cook the food.

Oh, cooking does wonders.

And never a sandwich that you find on the ground.

Not in the, well, not more than five seconds.

But wait a minute, so, all right, so you cook the food, but also cooking removes some of the nutrients from food.

Yeah, but not seriously.

You know, it'll kill a couple of the more dicey ones, like vitamin C and folate, but the others will be fine, and you will be so much better off eating cooked food in places where the water's dirty, that you'll be grateful that you did.

Okay, so that's, but how about the pathogens that are not organic, like mad cow disease, isn't that just a folded protein or something?

Yeah, that's a folded protein, that's pretty rare.

Hey, what's a folded protein?

You guys are like, hey, it's a folded, oh yeah, let's move on, because everyone knows what that is.

It's a misfolded protein, that makes it even worse.

What is that?

They're proteins in your body, and this one happens to get into the brain, and it's bad, and it's folded wrong, and it makes others fold wrong too.

Uh-oh, and then your whole brain folds wrong, and what a folded brain is a dead brain.

That's what I say.

Yeah, it's bad.

It's bad, you don't wanna get that, but it's rare.

Yeah, you definitely don't wanna get fold brain.

It's rare.

Okay, yeah, avoid the fold brain.

And it's something that cooking the food would not prevent.

No.

So avoid eating the brains of other animals.

Yes.

When we come back to StarTalk Radio, more with my interview segments with Anthony Bourdain.

We'll see you in a moment.

Thanks We're back on StarTalk Radio, I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

And we're coming to our final segment on this program where we're featuring my interview with Anthony Bourdain.

And Professor, you've been commenting on this, it's been great.

Just fleshing out what we're trying to explore, what it all means.

We came out of that segment talking about folded proteins.

You didn't know about a folded protein?

No, and I'm willing to bet a lot of people misfolded.

Everybody knows about a perfectly folded protein.

It's the misfolded proteins that catch most of America.

The origami protein where they messed up the third standard form.

Which is a danger that is unlikely and can't be avoided by cooking.

Both of those things.

Great, so I'm not afraid.

Don't need animal rights.

How good is cooking at killing viruses as opposed to bacteria?

That'll do that too.

Cooking is really helpful if you're trying to kill bacteria and viruses.

So it could be one of the greatest contributors to our longevity.

It could.

The fact that we started cooking food back when fire was tamed by cavemen.

Yes.

If you boil a person with a common cold, you will kill the common cold.

The question is how to find that perfect temperature before they die.

Well, that's kind of what your body does when it raises its temperature, is fighting bacterial infection.

So you are not completely crazy with that suggestion.

But I want to boil people to kill the virus.

But in fact, your body sometimes doesn't know how high to bring the body temperature and it can kill itself, right?

With a fever, yeah.

So there.

So I spoke with Anthony Bourdain about food in interesting, more exotic places, like food in space.

Rhode Island.

Name one place that has ever been there.

Or if we are going to go to Mars or we are going to go some place, just food at high altitude.

Later this afternoon, I am going to be speaking with the space station astronauts and I am going to ask them, and I am inspired by this conversation, I am going to ask them, since it is an international space station, do they ever get together and swap each other's foods?

Well, they do.

I have spoken to some astronauts about this and it is really interesting what happens to the pallet at altitude in an outer space.

Apparently, if you have a stash of hot sauce, you are the go-to guy in outer space.

They crave spice and chili sauce, Tabasco, some kind of good spicy relish, seasonings.

Something to keep in mind, if our next mission to Mars, would you volunteer to be there?

Would you advise NASA on it?

I would really be interested in going to Mars.

I cook and I had 28 years of it.

Somebody else can bring the food.

I'll bring the hot sauce.

You could be the spice man, I guess, how to make the food better.

Well, airline food tastes so differently on the ground and at altitude.

They have to completely reimagine it for what it's going to taste like up there.

So I think I'd be well, given my experience in Southeast Asia, I think I'd be a good choice for the master of condiments.

Marion, I'm intrigued by that.

I mean, I conducted that interview, but it didn't hit me until just now, that if your taste buds, your brain taste bud connection changes according to altitude, you need a different cuisine at every stratum where people live.

What do you know is known about eating at altitude?

I don't think the reasons for it are known.

It must have something to do with the loss of oxygen.

There's just less oxygen.

Less oxygen.

And even on an airplane, that is not pressurized to sea level.

It's pressurized at much lower, which puts less stress on the fuselage.

Because if they pressurize the cabin at sea level pressure, then seals begin to give, and it's...

I thought at first you were like, you were talking about seal the animal.

No, no, no, sorry, sorry.

You don't know how planes work.

You think they're powered by seals.

And so, and in the space station, the same thing.

So they might up the oxygen level to the same per breath, but the total air pressure is gonna be less.

And we know you can survive in lower air pressure.

So that's fascinating.

But things don't taste as good, and it's harder to boil water.

Yeah, well, it's so hard to cook an egg.

You can boil the water.