About This Episode

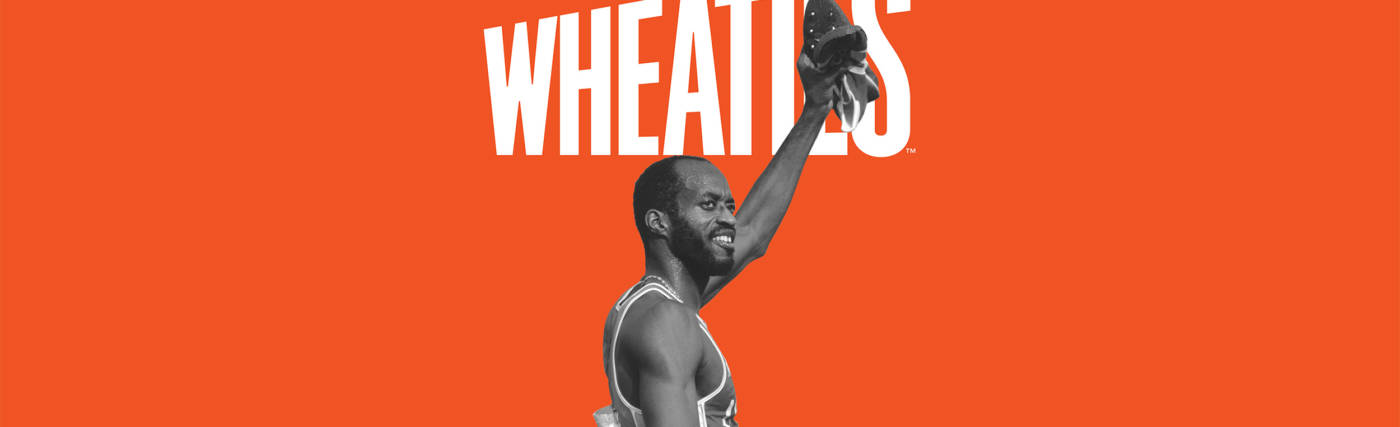

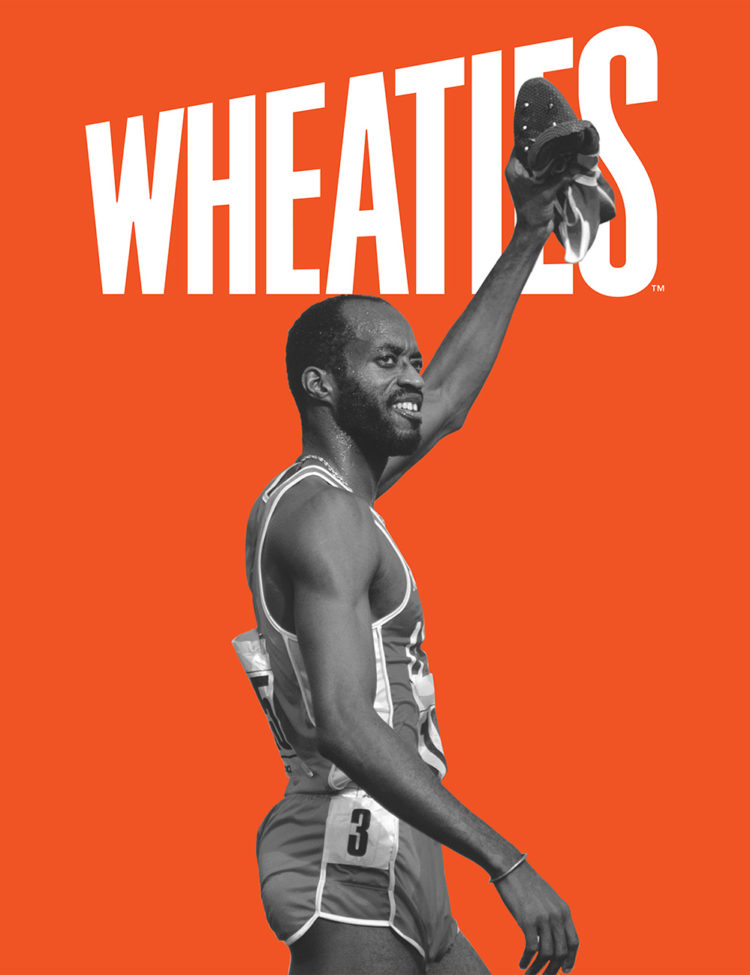

Can a physics background help you win gold? Neil deGrasse Tyson and co-hosts Gary O’Reilly and Chuck Nice discover how to use science to win, competing in the Olympics, and anti-doping with Dr. Edwin Moses, two-time Olympic gold medalist and the greatest hurdler of all time.

To start us off, Edwin tells us about his geek roots in physics and engineering. Find out why he was the “Urkel” of his school. Edwin explains how he had to learn to run track without having access to an actual track. You’ll learn about his time at Morehouse College and how he used science to approach running in a totally unique way.

Discover how Edwin used physics to crack the code of the 400m hurdles. We discuss how running on different tracks changes the race. Edwin explains how dance helped him work on his hurdling technique. You’ll also learn why the 400m hurdles is one of the hardest races in all of track and field.

Then, we dive into anti-doping, as Edwin serves as the Emeritus Chair of the United States Anti-Doping Agency. Edwin shares his experiences watching people around him cheat in the Olympics and how that urged him to stand up for fairness. We explore how doping is getting more sophisticated over the years. Is there a way to change the culture of high-performance athletes?

Lastly, Edwin reminisces on how he almost set himself on a path to become an astronaut. You’ll also find out why Edwin’s early adoption of the ice bath made other athletes laugh. All that, plus, we investigate his embrace of technology throughout his career.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTFord is electrifying its icons to keep the soul of driving alive while shifting towards an electric vehicle future.

The all-electric Mustang Mach-E gives you the bold style of a Mustang, along with the practicality of an SUV, an electric vehicle for people who want the freedom to experience the thrill of the drive while making sure their needs are met.

Get the excitement of a Mustang and the space to share it with five seats and a frunk, aka front trunk.

That’s right, it has room for you, your people and your things.

Learn more about the all-electric Mustang Mach-E SUV at ford.com/mustangmach-e, M-A-C-H-E.

Again, that’s ford.com/mustangmach-e.

Apple Card is the credit card created by Apple.

You earn 3% daily cash back upfront when you use it to buy a new iPhone 15, AirPods or any products at Apple.

And you can automatically grow your daily cash at 4.15% annual percentage yield when you open a high-yield savings account.

Apply for Apple Card in the Wallet app on iPhone.

Apple Card is subject to credit approval.

Savings is available to Apple Card owners subject to eligibility.

Savings accounts by Goldman Sachs Bank USA, member FDIC.

Terms apply.

This week on StarTalk, we look back at an episode where we featured Dr.

Edwin Moses, Olympic 400-meter hurdler, and learn how he applied the laws of physics to ensure that he would win gold in that event.

Also, we’re going to ask the question, can the application of science to human performance go too far?

Up next on StarTalk.

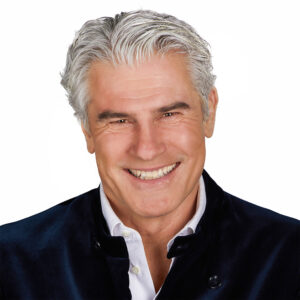

Welcome to StarTalk.

Your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk Sports Edition.

And we’re going to title this episode, It Ain’t Rocket Science.

Who do I have with me?

Of course, Gary O’Reilly.

Gary.

Hey, Neil.

Former professional soccer player in the UK.

What team did you play with?

Tottenham, Crystal Palace and Brighton and Hove Album.

All Premier League teams right now, so good news.

So you got traded a lot.

Does that mean everyone wanted you?

Does that mean no one wanted you?

Which does that mean?

All of the above.

So former pro turned sports commentator and we’re lucky to have you.

Thanks for being on.

Thank you.

Of course, as always.

And Chuck.

Hey, buddy.

How you doing, man?

I’m doing well, man.

All right.

Long time StarTalk co-host and comedian and dare I say actor.

Damn, damn.

Well, you know, you would be daring to say that.

So you got some gigs coming up.

We may be able to do a whole episode on where that’s going.

So it’s good to have you guys today.

We’re going to take a look at the the upcoming Olympics, Olympics 2021.

Of course, they were canceled, postponed out of 2020 due to the pandemic, wisely so.

And so just to get a sense of what it means to compete at that level, what people did to enhance their performance to get to these levels.

And we’ve got a former Olympian, Edwin Moses.

Edwin, welcome to StarTalk.

Good morning.

Thank you.

I know, man.

It’s like, this is crazy.

And not only Olympic gold medalist, not only the greatest hurdler of all time, but then…

Wait, wait.

He’s not a hurdler.

He’s a hurdler.

You said hurdler.

He’s a sheep herder, yes.

Hurdler.

No, here’s what people don’t even know.

You never know.

Olympics is getting every sport.

Sheep herding might be an Olympic sport one day.

And if it ever is or ever was, Edwin would have a medal in it.

Well, let me flesh this out.

Arguably, in fact, not even just are, the greatest 400-meter hurdler of all time.

Two-time Olympic gold medalist.

1976.

You surely would have won one in 1980, but we boycotted the Moscow Olympics in the middle, in Cold War, you know.

And then came back and then did it again in 1984.

So that’s spanning eight years, which is extraordinary, especially for that event.

And you’re an emeritus chairman of the board of the United States Anti-Doping Agency.

So we’re going to spend a whole segment on that.

You couldn’t resist it, could you?

That’s a low end Chuck joke.

You know, sometimes they’re just hanging.

You got to be.

I’m your chair, the Laureate World Sports Academy.

So let’s just resurrect some of this time of you as a hurdler.

You had a unique approach to the sport, to your steps, to your…

Just tell us what made your performance unique.

And my father used to run track, and he described to me what I was looking at, because I’m old enough to remember all this.

He described to me what I was looking at when I saw you in the 1976 and 1984 Olympics.

But I want you to tell everybody this.

Okay, go.

Well, the story starts at the time.

I was pretty much of a nerd in high school.

I studied.

I was a straight out nerd.

In fact, they could have had me playing the character of Urkel, because that’s how I presented myself.

I was smaller than everyone else.

I was pretty good in track, but I wasn’t a superstar.

I was unrecruitable going into college.

I couldn’t get the scholarship, so I got an academic scholarship to go to Morehouse to study engineering.

I was in a dual degree program, so I majored in physics and engineering.

At Morehouse, there was no track, no field, so I had to really look at everything differently when it came to being able to train every day.

I used to have to jump fences.

We used to carpool to three or four tracks.

I ran hurdles in the hallway.

I had a hurdle that I jumped in the hallway in the wintertime.

I was absolutely the most unlikely person to, three years after going to Morehouse, with no track, no field, jumping over fences to become Olympic champion.

So I had to reinvent everything.

And I started by really just technically with the hurdles and also using the science to really take a couple of meters off the track without anybody else knowing it.

So it was a combination of sheer will, going to the right school at the right time, being at an HBCU.

I went when I was 17 years old.

I was in a historically black college and university, HBCU, where I was able to thrive and study, and the academics was hard.

So I didn’t have time for frats and parties and girls.

I was physics and track and field.

So that’s where I put my…

So could it be…

I’m thinking of Bobby Fisher in this example, where he didn’t have the traditional path of chest training that so many other grandmasters and masters did.

So he had to be sort of inventive all on his own.

And then when he burst out onto the world scene, no one knew how to handle him.

Is it the fact that you had to invent this on your own, contribute to your unique running style when you finally ended up competing?

Yeah, when I was, I think, a sophomore or junior in high school, they had an event, you probably have heard of it, the four by 120, 480-yard shuttle hurdle relay where each team is running 10 hurdles, but one runs up the track and one runs down.

And I jumped in as a substitute and really taught myself how to run hurdles, so that was how I started.

And I think Tommy Smith, John Carlos, the 1968 Olympics, I was 13 years old, just getting ready to go to high school.

So that had a big impact on my whole outlook going in.

And then the 72 Olympics, which was a debacle for the United States, but in the 72 Olympics, there was a guy by the name of John Akibur from Uganda smashed the world record around 47.82 seconds from lane one.

And I imagine myself being John Akibur every time I went out onto the track.

I had no idea that four years later, I would go to the Olympics, win the gold medal and break his record.

But that was my take on track.

But let’s literally take a step back.

You must have had a smart idea about the biometrics.

Because of your physics background, you’d have an engineering, you’d have dismantled the whole event and then rebuilt it in your style, in your form that gave you.

Surely, did you have an unfair advantage is what I’m asking, I suppose?

It was my brain.

It’s called a fair advantage.

I taught myself to run, well, 13 hurdles.

I was a very good high hurdler.

I was running like 13.6 and I dropped my 400 flat down.

Just to be clear, that would be the 110 meter high.

110, yeah.

110 and then I ran from my sophomore year to my junior year.

I won the conference in 47.5 and I felt like I had made it in track and field.

Well, the first meet of my junior year, which was 76 at the Florida Relays, I started the season with a 46.1.

So that was like a second and a half drop right from the beginning.

And then when I ran the 400 hurdles for the first time, I had been doing a lot of power running, cross country running.

So I was in tip top condition.

All I had to do was teach myself how to run the hurdles 35 meters apart.

And the first time I did it, I found myself running 13.

I found myself using my left leg, which is the inner leg.

Closer to the curve.

And then I figured out that if I run 8 inches away from the inner line, which is where they measure the lane, versus 2 or 3 feet in the middle of the lane, I’m saving 3 to 4 meters per race, which is like 15 feet, anywhere from 12 to 15 feet.

So that was the first adjustment I made.

Wait, wait, Edwin, are you saying that the effective length of your path, because you start out in blocks, right?

Right.

And of course you have to stay in your lane, because you were hurtled all the way around.

So the length, the actual 400 meters, is not the center line of the width of your lane?

8 inches, 8 inches from the inner line.

I didn’t know that.

8 inches from the inner line.

So my endeavor was to run as close to the inner line as I could, whereas most people just run all over the lane.

And by doing that, I calculated the radius of the track and figured it out that I was saving 3 to 4 meters per race.

So that’s 12, 15 feet.

I was basically…

That’s some unfair advantage there.

That is amazing.

Edwin, that’s not nice.

So everyone was always asking me what the secret was, but I would never talk about something as simple as that.

They thought it was, you know…

Whatever it could be, but it was a combination of 13 steps.

I was a very good technician.

I ran with my inner leg.

My left leg was the one that I went over the hurdle first, so I was able to run closer to the line, which got me 12 to 15 feet in every race.

And that was the first thing on my mind coming out of the blocks.

If you ever see me come out of the blocks, I’m running almost on the line around those turns.

Wait, wait, wait, wait.

If you take 13 steps, that’s an odd number of steps.

Right.

So you’re saying your left leg only took you over the first hurdle, but your right leg is going to take you over the second one.

No, left leg every time.

Because they don’t count the step when you touch down, they don’t count that one.

They count the following one.

So an odd number of steps will have you hurdling on the same leg, an even number you would switch.

You switch.

Anyone wonder why he was world champion?

So what you’re saying is…

Wait, wait.

So if you go over with your left leg, and since we all run counterclockwise around the tracks, that left leg assures you that you will be closer to the line.

Because the right leg, you would land in somewhere else.

Exactly.

You gotta love this.

And if you run with your right leg, for example, your body has to remain within the vertical plane of 48 inches.

The planes of 48 inches is wide, so if your knee swings outside of the lane, technically, you can get eliminated from the race.

It’s a foul.

And they will call it in the Olympic Games.

Because there’s guys who run with their right leg going over first, and their left leg is what they call hooking.

Going outside of the lane.

Or even under the plane of the hurdle.

Speaking of that, speaking of fouls.

Your front leg goes straight out and over, and then your trailing leg, your knee goes over.

So there’s a whole drag motion there that has width to it.

And that’s what you’re describing.

That’s right.

It’s exiting the lane.

That’s right.

And if it exits the lane, that can be a penalty.

But if you’re left leg, you don’t have to worry about it.

And you’re running inside.

So let me ask you this.

And I will show my ignorance because I’ve always been just too afraid to ask this question.

When you see the guys running and they’re knocking over all the hurdles, are they being penalized for that?

Because every time I watch hurdlers and I see them knocking over the hurdles, I’m like, well, that guy sucks.

I could do that.

He’s just knocking stuff over.

Well, the Federation did a trick on that because when I was running, I think it took 18 to 20 pounds to tip over a high hurdle.

It would take 20 pounds of force to knock it over.

They reduced that to 12.

So during Roger Kingdome’s era and he won two gold medals, those guys were knocking over hurdles every time.

In my era, they had big lead weights on it.

One was flipped forward and one was flipped back.

If you hit any hurdle, it would take away from you.

Chuck, it had to go there.

He’s saying, in my day, it would explode in both directions.

And we had it hard.

But I get it.

They had to change the rules and keep up with the old dogs.

That’s what they did.

So basically, that’s what they did.

And with the track surfaces as well, they changed the bouncy elasticity of the track to make times faster.

So how did you cope with that?

Because you went from what I would call cinder track to what we call tartan.

It’s a very smart tartan track.

And that obviously energy rebounds back out of that.

So you being the engineer, how did you cope with the effect that that had in your technique?

Because you always say about the most important thing being the takeoff.

And first, before you do that, maybe there’s somebody listening who’s like me who is not a track aficionado like you three and doesn’t know what a cinder track and a tartan is.

Okay, rubber track.

The tracks you see now, the rubberized surfaces, that’s what he means.

It’s a trade name.

There’s about three different names.

Mondo, Tartan, Recratan.

There’s quite a few brand names, but they’re all essentially rubber and they all have a standardized compound that they must have.

I ran on dirt tracks in Dayton, Ohio.

It was cinder.

Here it is again.

I was on dirt tracks and my pearls wouldn’t break.

It was ground up cinders and sand, and they would spike it up and get a tractor to roll it down.

So it’s almost like you would see at a construction site right before they begin to put up everything.

It’s just rolled flat and heavy.

And we used to wear these long three-quarter inch spikes.

The problem with that is when you’re behind, you literally eat dirt.

The people in front of you are kicking up dust and sand, and it gets in your teeth and in your eyes.

The first time I ran on a rubberized track with great shoes was in the 1976 Olympic Games.

The first time you ran on one of those tracks was in the Olympics?

The first time I ran where I really, really felt the difference.

When I got brand new shoes that were made by Adidas, and they were custom made for the Olympic Games, and the Olympic track, which was a lot bigger and just perfect for running, I just felt like a Ferrari with big wheels on it, the total amount of grip that you could get, the elasticity when you take off.

I mean, you could feel the energy coming out of the track if you put it in.

So when I felt that in Montreal and ran around that track, I just knew it was going to be all over.

And the spikes are shorter for the rubberized track, correct?

Yeah, mine were like 9 millimeters, something like that, like a quarter of an inch, less than a half of an inch.

Right, right.

I knew once those shoes were on my feet, it was all over as far as I was concerned.

See, that’s confidence right there.

This is where being disadvantaged becomes the ultimate advantage.

Because when you have all the accoutrements, and they’re just giving you all the latest and the best, you’re like, OK, I’m spoiled.

But when you don’t have any of that, and then you get it, it’s like, oh my God, now this is an elevation.

I’m sure right now there’s a brother somewhere in Africa that’s skiing on dirt.

And when he gets to snow, it’s going to be over.

So Edwin, I’m a fan of dance, and I learned that you took ballet classes.

Was this specifically to help you work on your hurdling, or had some other just general interests?

My roommate at Morehouse, Josiah Young, Dr.

Josiah Young now, he was, I guess, one of the first male principal dancers at the Atlanta Ballet.

When we were in college, he was that good.

He had been taking it all of his life.

He would come out to the track and watch, and I would watch him compose dances and stretch and flexibility.

So I learned a tremendous amount about flexibility from him.

And I actually took one class over at Spellman in ballet and dance.

He drugged me over there because there was not too many guys that wanted to take it.

But I went over and took it because I was interested in the flexibility and the stretching part of it.

So I learned a lot about…

And hurdles in ballet are very, very similar.

I consider myself more of an artist and artisan when it comes to technically running the hurdles, but using the scientific background and being in tip-top condition, having the cardiovascular training, being a very, very good sprinter, everything.

So it sounds like you had combined mind, body, soul into one sort of holistic package.

Is that a fair way to think about this?

I would say so because the thing that I didn’t have was a track, which is the main requirement for track and field.

So I had to think of everything, flexibility, diet.

Yeah, I had to use every advantage and everything I could think of because just as today where you see Basketball Jones, that’s what they call them, walking around with a basketball and their baggy shorts and a couple of pairs of shoes in the bag.

I was walking around with track shoes and thinking about running all day long.

Well, we got to take a break.

So when we come back, Edwin, I want to get into what your role has been in the sort of anti-doping movement with regard to the purity and the efficacy of sports.

So stay with us on StarTalk.

We’re back at StarTalk Sports Edition.

We’re here with Edwin Moses, Olympic great, from a period where I was first really getting into the Olympics back in the 1970s, because that’s how old I am, 1976 and 1984 gold medalist, 400 meter hurdles.

And something I want to pick up in that first segment, Edwin, you won how many consecutive races?

107 of those were finals.

But it was 122.

Why does anyone even bother to say, here, just take the medal, I’ll go to meet you at the bar.

If everyone knows you’re going to win, do other runners believe that they might be able to beat you in that one time?

Do they think so?

Yeah.

Yeah, every time I ran, in someone else’s mind, they were in an Olympic final.

And I knew that every step of the way.

And a lot of people thought that me winning was easy.

But running faster, probably running more than the other athletes, I had to be prepared all the time.

And the faster you run, the more it hurts.

So I was the one that was in pain all the time.

But I was always ready for that.

And that was across almost 10 years.

How many times did you break your own record in those 122 wins?

1976, I broke the world record in the Olympic Games.

That year, I was breaking my own personal record all the way up until the Olympic Games, until my personal record became the world record.

I love that.

It’s hard.

It sounds easy at times.

Once you become a world record holder, it becomes hard to break your personal record.

You might only get two or three chances a year if you run 20.

That everything can go right.

Plus, do you need someone on your shoulder to try to push you?

Well, that’s what I didn’t have.

That’s the one thing I didn’t have.

And by the way, Dr.

Moses, I just need to correct you on one thing.

You said it sounds easy.

No, it doesn’t.

It’s not.

It looked easy.

When you see it on television, it looked like I was just branching away, but I had to run hard every time.

You look like you were just floating.

And everyone else was dancing and huffing and huffing.

You have to run hard to maintain 13, especially at the end.

So I had like a zone where I could run 13 steps slowly and run maybe a 48.3, 48.5.

And if I ran fast, then I could run as far as fast as I did down to 47 flat.

So there’s like a second range.

And your times are generally going to be in there, whether you run fast or slow.

It’s just a matter of intensity during the race.

You have an internal stopwatch, don’t you?

Yeah.

Yeah.

So did you, given that you could have made this calculation, I’m wondering if you did, there’s a calculation between how much time you spend airborne versus how much time, so in other words, the arc of every stride.

The higher you go, the more time you’re wasting coming back to earth before your foot hits the ground again.

Is there some ideal elevation, airborne elevation above the track that maximizes your forward motion?

And can I add to that and say, and is there anything that in that what Neil just said that changes the gate itself?

Yeah, that’s really the key.

Those two questions are really the key because there’s only one perfect takeoff point for the hurdle.

There’s only one point and I may be, for me, it’s about nine to 12 feet away from the hurdle that I’m taking off.

And for me, what I did was I never thought that I was going up into the air and going over an object.

I thought I was, really, I called it an exaggerated step.

And all I did, and because I was flexible, I was just able to take off at the right point, begin my movement, get my lead leg up, just the hurdle’s three feet high, so maybe three feet and two or three inches.

Wait a minute, Edwin, wait, wait, wait, wait.

Did you just tell me that your launch point to jump over hurdle is up to nine feet?

Yes.

Before the hurdle?

Yeah.

And did you notice that he just said that?

Like, oh yeah, everybody, everybody just, everybody can just put their leg up 12 feet away from something and just end up on the other side of it.

And by the way…

Like four feet on the other side.

Four feet on the other, so you would, so basically you were Jordan before Jordan.

That’s basically…

Yeah, yeah.

I used to kick basketball rims when I was at that age, when I was running.

Go up, kick it with my foot and come down like a cat.

I can jump.

I could have played basketball, but I really love track.

But basically, I also, another thing…

Wait, you could have slammed dust with your feet.

Yeah, exactly.

It’s horrible, like 2,400 back then, it’s like 2,600, so 35 meters.

I can’t even see the hurdle in front of me.

So I had to concentrate on the one takeoff point for everything.

And then count the number of steps and then wait for the hurdle to come in.

But I never really focused visually on the hurdle.

This will be interesting to you, Neil.

I always, you know, you’re a running platform and everything is moving, your mind is working.

But I saw myself as the stationary object.

And I saw the hurdle was something that was moving at me.

And most runners, they say, OK, I’m moving, there’s the object out there, I’m running it at.

But I saw myself as a stationary object.

My whole mental frame of mind was the hurdle is going to get to where I want it to be.

All I have to do is take off when I get there versus trying to aim at a spot that’s 12 or 15 feet in front of a hurdle.

This is this is called a Galilean transformation.

I transformed every day.

You are stationary, the track is moving under your feet.

And I wore contact lenses and glasses, and if it was raining or they fogged up, then I was in trouble.

So I had to look at it from a completely different way.

That with the stretching, the diet.

And I trained hard, I out trained everyone.

And I’d like to say that I became better than people that were much, much better than me because I stayed in it longer and just became better than them, outworked them.

Okay, so now tell me about at the time and even continuing decades to follow, there’s always been rumors of doping in one way or another.

Doping is, I guess, the broad category of what anyone would do to themselves, chemically, usually to the blood to enhance their performance.

So in your later years, in your, I guess, in retirement, you’ve become a big anti-doping advocate.

So could you just describe what your motivations were there and why it brings you back?

It happened at the 76 Olympic Games, which was my first one.

I was 20 years old.

And from my perspective, here I am.

I’m the best 400-meter hurdler in the world.

I’m running at under 48 seconds.

And I see these women from Romania and East Germany and Bulgaria and Russians, and they have more muscles than me.

And I was like, what the hell?

You know, looking at them in the bill, it’s the swimmers, the track and field people, not to mention the discus and hammer, but all of the runners.

If you go back and look at any book that had the 76 Olympic sprints, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1500, it was dominated by East Bloc women.

And that really bothered me.

One reason was because I came from an atmosphere where I didn’t even have a track.

So for me to take drugs and think about cheating was really behind comprehension.

And during that time, to be honest with you, most of the cheating was done in the East Bloc.

There were a few athletes in the United States, but most of those were like the discus, hammer throwers, the weight gods.

The strength, yeah, the strength sports.

Yeah, the extreme sports.

And so as my career progressed after 1980, it really changed in the United States as we led towards the 1984 Olympic Games because there was money on the table for marketing.

And it was Los Angeles, right?

The LA coaches out there that were willing to show athletes what to do.

And I began to fight it, quite frankly, back in the 70s.

And it was an uphill battle.

I was one of the few athletes that was not afraid to say anything because we were kind of like, sort of like a code of honor that they have amongst safe policemen, for example.

It was that kind of scenario.

Is it right, doctor, that you received death threats because of the actions that you took to change the sport and keep it clean?

Yeah, all kinds of threats, yeah.

So, these guys were doping, right?

And you’re still beating them.

You’re natural 100%, you’re clean.

They’re hopped up on whatever Andro, whatever they got in them.

And you’re still winning, which is why if you look very closely at the 76 race that you took the world record, there’s one dude in the back giving you a.

Finger.

The entire way around the track.

Is that on YouTube?

But wait, wait, wait.

So Edwin, you famously lost some race to some guy in Germany and then a week later beat him by 15 meters, right?

And this is like widely talked about.

So was he doped up when he beat you?

Or would someone accuse you of doping up in order to beat him right one week later?

No, I think he was one of my competitors that I ran against many, many times.

He was my archrival, Harold Smith from Germany.

And he was cleaning his whole career.

He worked hard too.

And we both started in the 76 games and we both finished in the 1988 games.

So our career…

So how could he, how did he beat you?

I was, to be honest with you, I was staying at a guest house of a guy who owned a Mercedes dealership in Berlin, and myself, and the guy named Maxi Parks.

We were out at the pool sipping martinis, and we should have been warming up.

So when we got out to the track, I just got out there late.

It was my second or third race ever in Europe.

And I just wasn’t paying attention.

Wasn’t paying attention.

I clipped the hurdle.

I clipped the ninth hurdle when he passed me.

And then I’d lunch at the wrong finish line.

And it was too late to beat him.

And at that point, it really didn’t matter.

There was no winning streak or anything like that.

Yeah, it didn’t break a winning streak.

And you kicked ass a week later just to…

It angered me.

That was very Michael Jordan to be motivated to say.

Neil, there’s a little phrase in there.

It angered me.

You see, when you hear an athlete say that, and then you look at the history of what that triggered, you realize how condensed that power was and how that was brought forward.

So that for me is a very powerful short sentence.

So this thing about doping, over the years it gets more and more sophisticated.

Yes.

In part to dodge loopholes, which I guess you just have to plug the loopholes, but also even if there’s no loophole, they do it so that they don’t get caught.

So how do you approach this?

How can you expect to be effective if this is like whack-a-mole?

You know, every next drug that gets developed, somebody does something different.

Well, there’s a couple of different approaches now.

There’s a deterrence model that they set up which does statistical analysis and kind of bases certain events, whether it’s biathlon or bobsled or track and field, on probabilities of athletes needing to take drugs and being in that type of event, when the competitions are, what countries they come from, what part of the training cycle that they’re in.

We also have new tools out there.

One is what they call a non-analytical positive.

The computer power, Neil, has really helped in the fight against dopamine because most people think of drug testing as like a litmus test.

You have urine and then you can test for a lot of things like the opioids, cocaine, steroids, stimulants, things of that nature.

And those are pretty much the same with the GCMS.

But then we also have a lot of other…

I guess no one tests for marijuana because then you’re just too…

They’re trying to minimize that because around the world in some places it’s legal.

And you’re dealing with a pool of athletes where it’s quite likely that they were using it.

I still know that marijuana ever helped anyone do any sport at all.

It can help in some sports, but basically it clogs up the legal system in terms of dealing with positive tests and that’s what they don’t want to have.

They actually raised the limits a couple of years ago, and I think they almost decriminalized it in sport except for in competition now.

Dr.

Moses, there’s something, selective androgen receptor modulators.

SARS.

That’s just what I was going to talk to you about.

Then I’ll step aside, sir.

They are not anabolic steroids, but they are precursors or they stimulate the production of anabolic steroids or some kind of hormones in your body.

Most of them are research drugs.

There’s a bunch of doctors from around the world that get these drugs from laboratories in China or from a lab under the auspices of doing research, and they convert these drugs and take them and package them up.

But they make your body produce more of the type of hormones.

And not all of it is just straight testosterone.

Androstenedione is an etiocolanolone.

There’s about five or six different drugs that they know are part of the reason that the body does overproduction and stimulates muscle growth.

But the research now, what did I say?

Non-analytical positive tests.

They’re looking now, they’re looking at proteins on a steroid chain.

And they’re looking at like 200, 300 different strands of DNA that they know will change.

And they know there’s nothing your body can do about it to reverse it.

So now they’re looking at the DNA strands on protein chains.

And now they’re able to go up to an athlete and say, oh, you’re 6’9, 290 pounds and throw in a javelin 300 feet.

How can you have breast cancer and be pregnant?

You know, it’s that sophisticated.

And that actually is what’s happening.

Women who present as though they have testicular cancer, for example.

Wow.

So it’s very, very sophisticated now.

And those markers are there because they’re an imprint of the doping that they have done, these small molecule things that they’ve put in their body.

That’s the imprint that they made.

The effect is immediately.

It may not be an imprint that it makes on the body, but it causes something else to happen that can be measured.

And then something else is not necessarily revealed in a blood test, but you do get it genetically out of it.

Right.

But they call those non-analytical positives.

We don’t even detect a drug.

We just know that this can’t be possible.

Some of these research jokes, are they sort of gene therapy?

And is this where we are?

That too, some of them are.

But how do we detect that?

We go right to the manufacturers of some of these drugs in the pharmaceutical houses and make agreements with them, such that we see the research way in advance, and we’re able to figure out when we see it, we recognize it.

That’s what they’re doing now.

You’re ahead of the story.

There’s a lot of detection out there.

And we have agents, we have guys from the DEA and FBI and Interpol that run security offices that do investigations.

We have a bunch of whistleblowers all over the world.

So there’s a lot of different elements.

It’s not just urine and blood anymore.

There’s very sophisticated intelligence that goes on.

Edwin, we got to take a break.

Can you hang out for our third segment?

Because we want to just sort of shoot the shit and just sort of speak in a completely disorganized way on topics that didn’t completely fit into the two previous segments.

With your permission, if you can hang on.

When we come back, more StarTalk Sports Edition with Olympic grade evidence.

We’re back, StarTalk Sports Edition.

It’s not rocket science with Edwin Moses, Olympic great in the 1970s and 80s for the 400-meter hurdles.

And a few things, Edwin.

I’ve always known, as I said, my father ran track and he told me about it, and I ran with him a few times.

The 400-meter race, with or without hurdles, I think everyone agrees is the hardest race in all track and field.

And would you, because it’s too long to sprint the whole way, but it’s not so long that you could pace yourself.

So is this a fair commentary on it?

Very fair.

The only other race that I’d say would be equal is the 800-meter, the way that they’re running that now, because they’re running like 141 and 142.

Okay, so it’s become, the 800-meters has worked its way into that.

But in 800-meters, you don’t have to lift your leg and go over something and then come down and sprint and then make it to the next hurdle and then go over something.

There’s no 800-meter hurdle is what you’re saying, right?

Yeah, so it’s the tough, they call it the man killer event.

So I just want to go a little further back on your story again.

So you had a chemistry set as a kid.

You were a geek kid.

You know, the word today would be blurred, black nerd, right?

That’s the term for that.

So tell me some other geeky things that you did.

Your father was a Tuskegee Airman, is that right?

My dad was a Tuskegee Airman.

He studied botany and biochemistry at Kentucky State.

He wanted to be a doctor, but he could never get into medical school back during those days.

In the early 50s, he tried Indiana University, a bunch of schools, and he was very frustrated.

He went into education.

But I grew up looking at my dad’s chemistry books, organic chemistry books.

I didn’t know what I was looking at, but I was just turning pages and fascinated.

Algebra and geometry books.

We had a whole basement full of his college books.

Today, many people sell back their books, or they just, you know, the idea that a book is something ephemeral is so anathema to me that I’m glad that you benefited from kept books.

We had the Children’s Encyclopedia.

We had the Encyclopedia Britannica.

I’ve done everything from making a volcano with potassium chloride or whatever it is and blowing it up in school.

I had a big hill.

I had fossil collection, insect collection.

I had frogs and snakes.

I had butterfly collections, launch model rockets, had a chemistry set and a biology set.

So I was just total nerd after my dad.

I’m so loving that.

And I had braces and big coke bottle glasses.

So I used to have to fight a lot.

I would get bullied.

You really were uncle.

My house was uphill.

So after I used to get out of school early and leave like five minutes before and start running uphill with my saxophone, I never got caught.

So that’s one of the reasons I was able to get in shape because I wasn’t afraid to run uphill to get home.

And that’s before bullies were outlawed.

You know, bullies are like a whole thing today.

You know, their sense of the principal are kicked out of school.

And back in our day, they were just a fundamental part of life in high school.

And in fact, you know, people forget that the movie Back to the Future, that whole storyline exists only because there’s a bully.

Just think about how that is and what that works.

Today, that wouldn’t be tolerated from an administrative level, even if it was, you know, the terror of the kids in the school.

So you had all this kind of backdrop.

And I’m just loving, I love hearing it.

Let me ask you, you approach the whole sport holistically, as we’ve described, or just as one generalized package, rather than send out Interpol to catch cheaters, is there a way, and I don’t want to sound a little new agey on you, but is there a way to just change the culture of high performance athletics so that no one would even think to do such a thing?

Yes, yes, Dr.

Moses, can you please change human nature?

Well, I was a chairman, interestingly enough.

You know, he might have a solution, Chuck.

I was the chairman of the World Anti-Doping Agency’s Education Committee, and we realigned the education to really, even at a young age, as early as like 3, 4, 5 years old, to really kind of integrate ethics and fair play in sports at an age-appropriate level, even if you’re 7 years old or 12 or 15.

For example, a kid, if you put together a group of nursery school kids and you let them run across the room, 20 meters or something, you go ahead and put one kid in front of the others and watch the other ones go off.

They know innately what’s cheating and what’s fair and what’s not fair.

And so when you begin to talk to them at that appropriate level, why it’s important to play by the rules, understand the rules, be a great student.

In that example, you gave an obvious advantage to another student.

That’s right.

They know that right off the bat.

So when you can engage them at age-appropriate levels with those principles, then you can begin to deter the use of steroids.

And then you have to talk about the risks.

There’s risks and rewards that athletes are willing to take in order to become a world-class champion, become an Olympic champion.

You mean health risks or penalization risks?

Penalization risks.

Right.

And physical risks as well as physical risks.

I don’t think you should talk about physical risks because…

As physical risks.

Because there might be some future doping thing that has no other side effects.

And so to say, don’t do this because you’ll lose your testicles or whatever, is that the only reason why?

No, you don’t want them to do it because it would give them an unfair advantage.

The rest of that is just a byproduct.

So, okay, Dr.

Moses, your athletic career is nothing short of stellar.

The campaign and your advocation for a clean sport is amazing, but do you not regret having passed the cognitive test to be an astronaut, not to have gone to space?

Yeah, the story is, I got drafted in 1975, passed the test to become a Navy bomber navigator, and the war was still going on.

I think I was a junior, sophomore, junior at Morehouse Steel, and a recruiter came by.

He was from the Marine Corps.

He said, well, it’s another one of my physics partners.

We both got drafted on the same day.

Our numbers came up.

So we were definitely going to Vietnam.

And he said, I give you guys a choice.

We said, what’s that?

He said, you can go to Vietnam with an M16 on your back or an F16.

We said, we’ll take the F16.

And we were supposed to go down to Pensacola, me to train to become a bomber navigator.

My vision was not good enough for a pilot.

And then that was actually going to be the path to becoming an astronaut for me because there was no black astronauts back then.

And they were recruiting us because we were physicists and engineers.

So I had that path and was very interested in it.

And then the next year I went to the Olympic Games and all bets were off.

What a surprise.

Yeah, it was.

Unfortunately, I cannot run to the moon.

So I’ll be here, guys.

I’ll settle for the Olympics.

Okay, Dr.

Moses, looking forward and hopefully in 2021 and Tokyo, are we going to get on top of sport and make it clean, or are we going to rinse and repeat the episodes of previous Olympians?

Well, generally Olympic sport is clean.

There’s a few bad players that promote the use of drugs and write prescriptions, and it’s all over the world in all different sports, including here in the US.

The majority of athletes want to be clean.

And because of the work that we’ve done at USADA, they trust us to do what’s necessary to keep the playing field level for everyone.

If athletes test positive, we have to do something about it.

So they have the confidence that there is someone there that’s going to keep the playing field level.

And that’s been the greatest thing, one of the greatest pieces of work that we’ve done.

We’ve actually been able to clean the playing field up and make it level and have the athletes think that there are no exceptions.

Whether you’re a Lance Armstrong or whoever else you may be, that there’s no exceptions.

That we in the United States, we go after anyone, including the 85-year-old little old lady who’s a cyclist on weekends.

There’s so many different athletes that test positive.

And there’s a lot to make innocent mistakes, especially with supplements or…

Did you just say this in 85?

The heartbreaking thing is inadvertent use.

Like a substance that’s in a…

Ingeritol.

85-year-old lady with muscles, busting people out.

Yeah, supplements, you know, supplements that are tainted.

Those are the heartbreaking cases.

Or someone who just missed tests.

You know, they’re a knucklehead and they just missed a couple of tests every now and then.

You only get three.

Those are the heartbreaking tests.

The majority of people want to compete, claim.

So can I ask you…

I want to ask you a philosophical question as we talk about this.

So, you know, people take these things when they’re cheating for the promotion of anabolism and then also for recovery time.

So, let’s say, for instance, you had a drug that did not promote the growth aspect, but did decrease recovery time…

Improved healing.

Yeah, that improved your healing.

Would that be okay if something like that were…

Or is philosophically, it’s just the whole act of utilizing a substance that is the problem, period?

Well, in cycling, they use corticosteroids.

They’re mostly used for recovery to help the body recover.

Because if you look at the Tour de France, there’s no way that you can pedal like that or do any high-intensity sport for 18, 20 days in a row without a lot of physical damage and eventually your body’s going to break down.

So all those recovery drugs that are pharmaceuticals, that aren’t normal, a normal person would take, just to feel good, those are all banned.

Those are all banned.

There’s certain ways that you can take them, injections in a joint, for example, but you can’t inject them into your skin, can’t rub them onto your skin, just like you can’t do testosterone and whatnot.

So I use ice.

That was the best recovery method.

And when I was doing it back in the late 70s and early 80s, everyone laughed at me, but now every NBA, soccer team, NFL, baseball, you see their guys in ice immediately after the game.

I was the first to do that.

They laughed at me back there.

H2O is a major additive.

50 degrees, 20 minutes.

So you were…

I mean, apart from being this holistic athlete and the yoga, the stretching, the diet, you embraced technology.

You were one of the first people to have one of those…

Heart monitor.

Yeah, the Finnish company Polar.

Polar.

When was that, that you started to take that sort of tech onto the track and use it?

That was 78.

I went to Finland to run about three track meets and met this Finnish masseur, Ilpo Nikila, who stayed with me for almost my whole career.

And they showed me the monitor.

And then one year I got injured and went up and trained in a place called Vyromarkki, the Finnish training center, for six weeks.

And they gave me a new one, and I just found a way to incorporate that into my training, because I knew how far I was going.

I measured everything off my cross-country courses around the track, and I used it to be able to moderate how much time I would use between races.

And I’ve still got all the charts, the original charts.

And then I plotted it on the old Epson QX10, which had about 20 discs to load up just to be able to count to five.

But I saved all that and printed it all out.

Oh, man.

You’ve got a museum there.

So Edwin, when is the biopic coming out?

Actually, we’re working on it right now.

We have a treatment.

I don’t know which way it’s going to go, but we actually are working on it right now.

Is it based on a book or is it just something out of just going straight to film?

And who do you want to play young Edwin Moses?

I don’t know if it’s going to be that kind of movie.

It really just depends on how it’s marketed and who picks it up.

But I do see scenes in my imagination.

I see scenes of me asking the teacher, can I go to the bathroom, run into my locker, get in my clothes, grab my saxophone and bust it out the door uphill with the kids chasing me.

I see that at night as a part of the movie.

Let me channel some of my father’s spirit energy here.

We lost him a couple of years ago.

Just that it’s an honor to have you on the show to talk with you about what you did in that race that all of us were agape at as we saw you win with such grace and such poise.

It’s great to see that you’ve continued.

It’s great to learn that you’re a blurb from way back.

And if we may, when the Olympics comes a little closer, if you’re not heavily tapped by all the Olympic outlets, can we bring you back on and just shoot the shit about the Olympics?

Absolutely.

Because the world comes together just to think about the sports that keeps us together, really, at some level.

So it would be great to have you back on when the time comes.

All right, we got to call it quits there.

Sorry, sorry, Edwin.

We got to run.

Yeah.

We don’t want to talk no more.

We got to run.

We got to hurdle out of here.

Also, it’s pretty clear that Edwin was destined to greatness because the dude’s name is Moses.

Deliver us from the desert, Edwin.

So anyhow, we’ll call it quits there.

So Chuck, good to have you.

Gary, as always.

Pleasure.

Dr.

Edwin Moses, it’s been an honor.

I’m Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal natural physicist.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron