About This Episode

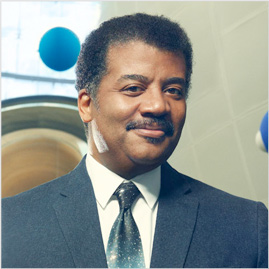

Could you play Quidditch on Jupiter? Javelin on Mars? On this episode, Neil deGrasse Tyson and co-hosts Chuck Nice and Gary O’Reilly answer fan questions about low-gravity physics, the weight of Thor’s hammer, aerodynamics and more with physicist Charles Liu.

We explore games in Star Trek like Parrises Squares and other geeky games. How much does Thor’s hammer, Mjolnir, weigh? How high could a high jumper jump on the moon? We break down gravitational acceleration and do some physics calculations.

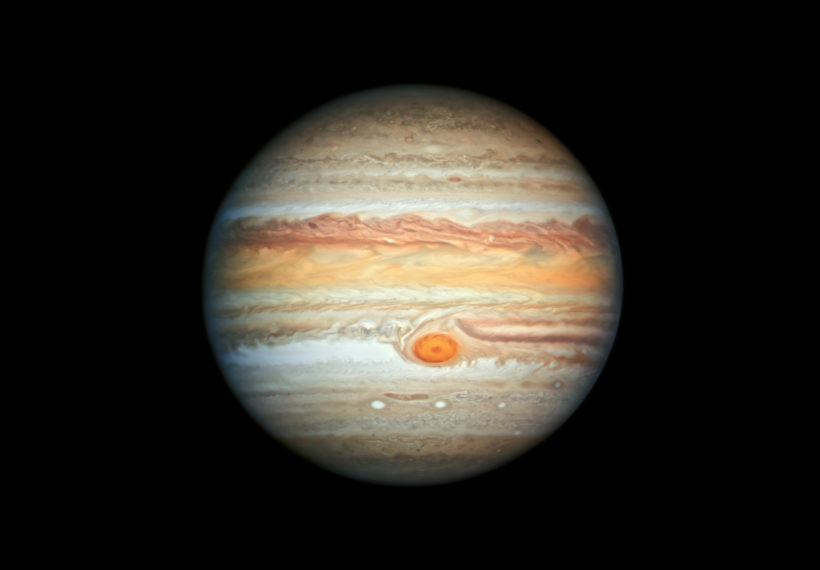

Could you play a sport on Jupiter or Saturn? Find out what it would be like to play Quidditch on Jupiter. Would you be able to shoot an arrow farther on the moon? Could you throw something into orbit? We discuss golfing at high altitude and the effects of air pressure and humidity on the movement of the ball.

Will we ever reach a point where we can’t create any more world records? Could we just start modifying people? We also get into the FIFA World Cup in Qatar. What challenges will they have to watch out for? How will they work around the heat? All that and more on another grab bag Cosmic Queries!

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can watch or listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTI would play near the surface.

At some atmospheric pressure, that would be similar to what we can survive, but then you’d be up in the air.

There would be a gravitational pull, but there wouldn’t be anything to stand on.

So Quidditch would indeed be an ideal thing to play there, but you’d have to have some gas masks on because it smells a lot like methane and ammonia out there.

So, sign me up.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk Sports Edition, and we’re going to do a grab bag today.

Love me some grab bag, and of course I got my co-host Chuck Nice.

Chuck.

Hey, hey, hey, Neil, what’s happening?

All right, all right.

And Gary, Gary, how you feeling, man?

I’m good.

Yeah, yeah, Gary O’Reilly, former talker pro.

And who do we have to help us out with grab bag?

A returning champion.

A returning champion, our go-to geek-in-chief, Professor Dr.

Charles Liu.

Whoo-hoo.

Hi, Chuck.

Hi, Gary.

Hi, Neil.

I am a total card-carrying geek, but in the same room with Charles, I am a rank amateur.

You are too modest, sir.

It’s such a pleasure to be here with you all and have a great time.

It’s a grab bag.

We don’t know where these are coming from or where they’re going, but they are questions from our Patreon supporters, and anything and everything goes.

So, Gary, why don’t we lead off with you?

You got questions for us?

I certainly have, and they’re all sourced from our Patreon patrons, so thank you very much.

Stick with us because we might well be asking your questions throughout the show.

First up, Christopher Fowler.

He says, greetings to the good doctors, Lord Nice and me.

Interesting.

Oh, we’re going straight for sci-fi.

In Star Trek, The Next Generation, there was at least one episode with a game called Parisi Squares.

Am I pronouncing it right?

On startrek.com, it describes a sport as one played by opposing teams of four wearing padded uniforms and using an ion mallet.

What kind of sport is this and could it be possible to actually achieve technological advancements to allow an ion mallet?

Just to be clear, I’m already out geeked because I didn’t see the show.

I don’t know anything that you just said in that question.

And Charles is right all on top of it.

So there you go.

Parisi Squares is a fascinating game that no one knows how to play because it has never been shown on screen actually.

So it first was mentioned in the first season of StarTrek The Next Generation when the Binar episode.

You guys remember that one?

11001001 and they were fixing the enterprise and so the crew had time to take it easy.

And so four members of the crew went to go play Parisi Squares with the team of the people who were working down at the space station to fix the enterprise.

They seemed to be carrying suitcases presumably containing the Ion Mallets and they were kind of padded like lacrosse players but they had like shorts on and stuff like that.

So since then we really have no idea how it’s been played but it’s been mentioned over and over again.

And actually, it doesn’t sound like the rules have stayed roughly the same.

It started like this, in this episode, like a friendly matchup where like maybe four guys and four other guys would come together and they would play each other and like maybe whack some sort of ball back and forth with some sort of a mallet like croquet or something like that, right?

But then it got darker.

Like there were riots involved.

People could get hurt.

Ryker, I think at some point, got like so hurt in Parisi Squares that the doctor warned Dr.

Crusher at that point, right?

Said, you know, be careful because next time you’re going to break your neck and I won’t be able to fix that so easily.

And then in Star Trek Voyager, the doctor, the emergency medical hologram had created a temporary holographic sort of fake family and his fake daughter, holographic daughter played Parisi Squares and died.

Died and they couldn’t even fix her with all of the medical technology on Voyager, supposedly, according to this holographic thing.

I mean, that’s pretty scary.

Wait, the hologram died?

Yeah, in the fictitious story of the Dr.

Keating family.

Why can’t you just fix the hologram?

I don’t get it.

That, actually, the episode is pretty cool.

You got to watch it.

It’s kind of cool.

I’m sorry I didn’t watch seven different generations of Star Trek to piece together this story.

I’m sorry.

I don’t have the geek credentials.

It’s all streaming.

You can get to it.

It’s not too late.

Anyway, but the reality is I think Parisi Squares is something like hockey.

Something like hockey, but I really don’t know what, because unfortunately it’s never been shown on screen.

I would like to think that it’s kind of like the game Triad, which was played on the Battlestar Galactica, the original series back in 1978-79.

That was a cool game.

But we saw people playing Triad on that show.

We never saw people playing Parisi Squares on StarTalk.

Tell me about this ion mallet.

What would be the benefit of having an ion mallet?

Well, you know how Mjolnir Thor’s hammer is like a serious mallet, right?

So I imagine that the ion mallet was like an energy version of Mjolnir’s hammer.

And what was happening is that this big fat energy ball of some kind is zipping around the court, right?

And you got to run uphill, downhill, around, back and forth to get it.

And the only way you can get is to whack it with the mallet.

Kind of like the bludgers in Quidditch.

You got the big things whacking the ball back and forth because you don’t want to get hit by one of those big balls coming at you.

That’s my guess.

And because they’re played on spaceships as well as in stadiums, they got to make the mallet small enough that you can carry them around.

Not just like big hockey sticks or lacrosse sticks.

So the ion allows you to change their size and their effect areas without having to make a very large piece of metal or wood.

Oh, interesting.

That’s my guess.

Okay, so you know how much Mjolnir weighs for Thor?

You figured this out once, didn’t you?

I did, but I got it wrong because I got it out of heat.

Really?

Yeah.

Oh, tell us.

Yeah, I calculated because they said, this had nothing to do with that game or the person’s question, but you did mention Mjolnir.

You got to go with it.

Take it where it goes, Neil.

I did calculate it and in the Thor film, they said it was forged in the heart of a dying star.

And I said, well, we’re astrophysicists.

We deal in dying stars, so I got this.

So you can make a hammer out of white dwarf material, but why stop there?

You make one out of a neutron star.

So I did this and I got the volume of Mjolnir because I have a replica of it.

And so once you get the volume and you get the density, you get the total mass.

And it has the mass equivalent of a herd of 300 million elephants.

Oh, that’s all?

Who’s actually measured a herd?

Wait, just hold on.

So that’s where the Hulk tried to pick it up, but he couldn’t.

Okay.

So I put this out there proudly.

And then it was like, you’re wrong, Dr.

Tyson.

Mjolnir actually weighs.

This is an interesting usage of the word actually, about a completely fictitious object.

So apparently Marvel issued a Thor trading card in 1991 that reported the precise weight of Thor’s hammer as 42.3 pounds.

Now, I think my answer is way better than that one, even though it’s wrong, okay?

That must be a commemorative 42.3 pounds, because it’s not quite the answer to life, the universe and everything.

And I had a fan in the audience.

This fan said, Dr.

Tyson, on that card, they didn’t say which planet it weighed that much on.

I said yes.

They were helping me out.

You look bad for me.

That’s kind of cool though.

That’s a really cool observation.

So that means it’s all magical.

It’s magical.

It’s not a literal weight.

He really needs the power of honesty and integrity to lift it.

Worthiness.

Worthy, excuse me.

Worthy is the word.

There was actually a period of time a comic book series called The Unworthy Thor where for a moment there he could not pick up the hammer because he was briefly unworthy.

That’s how they played it, Chuck.

That’s exactly how they played it.

Let’s keep going.

I love that question.

Let’s get some more.

All right.

You want to go, Chuck?

Dale Bloomfield.

Dale’s been quite busy with the questions, but we’ll start with this one.

If we were able to have a high jump event on the moon, what height do you think people could get to?

And also, because it’s stuck in track and field, obviously, how big a field would we need if we had Javelin on the moon as well?

Chuck, this part’s for you.

Chuck Nice.

Chuck, if you don’t read this question out, then the Eagles won’t make the playoffs this year.

Thank God for you, Gary.

Thank God for you helping my Eagles out.

There you go.

Well, there’s no atmosphere, but something can go through the air on the moon if you put enough force into it.

Now, the surface of the moon has a gravitational acceleration about one sixth that of here on Earth.

So, you could imagine basically you’re going to be up in the air six times longer.

Yeah.

And so, whatever you can add in terms of your ability to jump.

So, right now the world record for high jump is about eight feet.

So, if you jump eight feet now, but that’s all the time you have in the air, multiply that by six and that’s the minimum amount of gain you would have.

So, 48 feet.

48 feet.

Wow.

Because it’s an acceleration, it is actually a quadratic term in the distance traveled.

So, you can make a quick calculation, you know, VOT plus one half AT squared and you may wind up with higher depending on how much push you get off the ground with your muscles.

Okay, Charles, I think you’re wrong in one part of that calculation.

Uh-oh.

Astrophysicist slap down.

Charles, I’ll meet you in the octagon.

Okay, here’s why.

Place some pre-C squares.

Okay, so Charles, you would calculate the high jump by going from this person’s center of mass and let’s say the jumper is seven feet.

I think they’re pretty tall, but let’s just use round numbers.

So, their center mass is, let’s say, halfway up.

So, they’re only going four and a half feet above their center of mass to clear the bar.

Okay, so now you take that four and a half feet, multiply that by six, and then you get 24, five, six, seven.

So, then we’ll jump 27, 28 feet rather than the 48.

So, I think that’s how you need to do the calculation, I’m pretty sure.

That may well be true.

The other thing here is we’ve seen the Fosby flop as the go-to technique to get a world record here on Earth.

Do we think that that technique, which is almost a vertical takeoff, could apply to that technique going that high on the moon with a jump?

Oh, that’s a great question.

Because would you then have to have a running and then try and kind of almost like fly over the bar?

Right.

It almost becomes like a pole vault, right?

The human body is going at such high altitudes.

Because pole vault is like 20 feet-ish for a world record.

Clearly, whether it’s your 30-ish feet or my 40-ish feet, it’s still up at such a high level that the human body’s reaction or position may have to be changed to be optimally good.

That’s a great point.

An interesting point.

So, Charles, what you’re saying is I can twist my body and go backwards over the bar in the short time that I’m airborne.

Correct.

If I’m airborne six times longer, I…

I might be able to optimize for something else.

Or, just a minute now…

Here we go.

Their forward…

Oh, oh, oh, Charles, Charles.

Their forward motion is tuned so that they leave the ground such that they’re at their highest point by still moving forward.

Right?

That’s right.

But that’s pretty close to the bar, because they’re not like, how long are they airborne?

But if you’re airborne six times longer, you’re going to have to leave the ground sooner.

Yeah.

So the bar is over, like, on one side of the room.

You’re on the other side of the room.

And when you land, you’re all the way over there as opposed to inches away when you take off.

Exactly.

It’s much more of a parabolic arc.

Think about the floor routine in gymnastics where they do all the tumbles and then all of a sudden, gymnasts will just pop and produce a double somersault and then land on their feet, right?

What if you took that kind of technique towards clearing a bar for a jump on the moon?

Because you get serious vertical loose.

They’re able to do that.

The floor is sprung, I agree.

Right, it’s because the floor is helping them, is returning energy to them to do that.

But then again, less gravity.

You would have to do that same floor.

Talking about the physics and return energy.

We’ve got to get an honorary degree for Chuck.

Of course he does.

Then you’re balancing that strong floor and return of energy against the reduced gravity on the moon.

Correct.

Yeah, so it’s very interesting.

And of course, none of us have taken yet into account the fact that if you’re actually on the moon, you’re not just launching yourself up into the air, you’re launching your entire spacesuit.

So you’ve got a lot more mass to work on, unless you’re sealed indoors in a habitat or environment.

So maybe three or four years from now, when we actually have a moon base with human beings living inside some building, we’ll find out exactly the answer to this question.

Nice.

Experimentally.

Cool, cool.

Guys, we’ve got to take a quick break.

This is StarTalk Cosmic Queries Grab Bag Edition with our geek in chief, Charles Liu will be right back.

We’re back, StarTalk Cosmic Queries Sports Edition.

I got our geek in chief, Charles Liu.

Charles, you are a professor of astronomy and physics at City University of Staten Island.

I get that correct?

That is absolutely right.

All right, so who’s next on the question line there?

All right, we got Jay Hunter.

These are Patreon exclusives that we’ll move into, for those of you who support us through Patreon.

And by support, I mean give us money.

Thank you, thank you.

Jay Hunter says, what up Chuck, Dr.

Tyson, Dr.

Liu and Gary?

What would playing soccer look like on our neighboring planets?

What sports would be possible to play on Jupiter and Saturn?

Well, Gary, first of all, Gary, what planet would you like to play soccer on?

Yeah, let’s ask him that.

This one.

We’re going to change the game completely if we take it off well, because if we go to a planet where there is less gravity, do we need a heavier ball?

If we have a heavier ball, can we actually kick it?

Are we going to be, if we use the similar ball, we can kick it forever, so the field’s going to be three miles by two.

And if the air density is much lower, then you’re not going to get your Magnus effect.

Nope.

So you’re going to get all those fancy kicks.

So there’s a lot of things going against it.

It would need to be something close to the gravity and atmosphere that we have here on Earth.

For it to look like soccer.

Yeah, totally.

Hey, you know what?

If it were on a planet with lighter gravity, Gary, don’t you think that maybe we could increase the size of the field and increase the number of players per side?

That would work.

That would make it very simple.

That would work.

It’s just the fact that at some point, you’re going to have to cover distance as an athlete and you’re having to cover more distance.

So, you know, maybe you could supplement that by having more players on the field at the same time.

Or you actually have co-teams.

So the field is big enough where one team takes one third of one half, I mean, one half of one half, the other team takes a quarter, and then they’re not allowed to go into the other zones.

So it’s almost like two games being played at the same time, but they don’t get to intermingle.

That sounds like a cacophony, but still.

Yeah, you know what it sounds like?

It sounds like whatever is going on, whatever the circumstances of the planet, the atmosphere, the gravity and everything, we should just invent new sports tuned for that planet.

Absolutely.

That’s what it sounds like to me.

Now that’s a good idea.

What do you think of that?

Forget trying to take Earth’s, rather than port Earth sports there, just invent a brand new thing.

Why not?

Yeah.

Hence, Parisi Squares.

Or, if we could actually fly on brooms, we’d invent Quidditch.

Quidditch.

Right.

You have kind of three-dimensional basketball, if you’re able to float or leap or do sorts of things.

So you’ve got hoops in different, in a tube, and they’re on different edge surfaces.

So there’s all sorts of things you could invent and play with.

We invented basketball, football, soccer, tennis, golf, et cetera, et cetera.

We can invent some new ones.

So Charles, just remind us that about, I mean, Jupiter and Saturn are gaseous.

So how do you get around that?

Jupiter and Saturn are gas giant planets, which means that their atmospheres take up a huge percentage of their mass.

The surface down at the bottom of, for example, Jupiter, this massive thing, it’s actually liquid.

It’s liquid hydrogen, metallic.

So it’s solid, but it’s also liquid metallic and it’s kind of weird.

So playing on Jupiter or Saturn would be really, really hard.

Anyway, you’d all be crushed by the atmospheric pressure long before we even got down to the surface, be it solid or liquid or metallic or rocky or stone or whatever.

It’d be like trying to play at the bottom of the ocean.

You’re exactly right, Chuck.

So I would play near the surface.

I would play near the surface at some atmospheric pressure that would be similar to what we can survive.

But then you’d be up in the air.

There would be a gravitational pull, but there wouldn’t be anything to stand on.

So Quidditch would indeed be an ideal thing to play there.

But you’d have to have some gas masks on because it smells a lot like methane and ammonia out there.

All right, so we’ve already had a sporting event off world.

You mean golf on the moon?

Yes.

So does that lead us to, rather than competing against each other with atmospherics that don’t work for the human body, is it not now a kind of projectile sport that we enter into like golf?

It might be.

It might be.

I’ll tell you what sport I would like to play in space.

Just try it a little bit and see what happens.

Cornhole.

If you toss the thing the wrong direction, it misses by a mile and it keeps going forever, right?

So it becomes almost like archery with a bean bag.

Oh, archery is even as good too.

Yeah, except that if you miss and you hit someone’s spacesuit, that’s not a very nice day.

Yeah, puncture the spacesuit.

How far away would you want the target to be if it were archery?

On a planet or on a moon with less dense atmosphere, less gravity.

What would you do?

Would you like?

I mean, we’ve had…

Yeah.

I’m putting the target on Earth.

Actually…

Let’s see how good you really are, Katniss.

That’s Hunger Games right there.

Okay.

So, I would say actually you don’t move it that far.

Because archery has the arrow moving so fast that gravity only affects the overall flight by a few inches or a few feet.

Good point.

So, what you still want sort of your eye…

You’re not lobbing arrows on an arch.

You’re just aiming straight down instead of lobbing.

So, there’s no parabolic trajectory.

There is, but it’s a very flat parabola.

So, that’s what that is.

So, I wouldn’t change the distance that much, but maybe the target size.

Plus, consider if you did want to change the distance, it becomes much harder to be accurate.

Because the tiny angle off from the launched arrow, that angle just gets wider and wider as you get out there, and you’ll start missing targets completely.

So, what’s the use if it’s easy?

But what’s the use if it’s impossible?

There’s the other side.

That’s the other side of the argument.

Absolutely.

Yes, it is.

It is.

It’s that balance.

Which is when sports are balanced like that, it’s what makes them the great thing they are.

When it’s impossible to achieve or just too simple to achieve, then it doesn’t hold that greatness.

You see with some of the sports.

And just quickly, we dangled one of the questions, how far would a Javelin go?

Yeah.

We’re thinking that would go six times farther on the moon.

Is that right?

Yeah.

I think that’s right.

I would agree with that statement.

So let’s take the world record times by six and for the Javelin.

That’s about a hundred.

And put an unsuspecting astronaut on the other end of the spear.

Wait, there’s a technicality here because in our lifetime, they added an atmospheric drag element on the tail of the Javelin so they can keep it in the stadium.

They actually wait because the Javelins themselves are weighted and they can maneuver the position of the weight within the shaft of the Javelin.

And they needed to bring it down because what they found was, I can’t remember his name.

Oh, no, I think he was Hungarian.

He was basically throwing it onto the track at the far end of the arena.

That’s great as long as not people running on it.

So they had to redesign the Javelin so as they didn’t fly as far.

Because they were throwing over a hundred meters.

Right.

What I’m saying, isn’t that an aerodynamic drag that they put on it?

Because if it is, then on the moon you’re not going to have the aerodynamic drag.

You just simply need a bigger boat.

That’s right.

But if you increase the mass, then you reduce the velocity.

Just to compensate?

That’s what a Javelin thrower can make.

Yes, you will.

Just to keep it in the stadium.

Right.

Okay, there you go.

So basically it goes from Javelins to small trees.

Throwing small trees today, people.

Instead of saying to an athlete, keep it in the stadium, it’s saying just keep it on the planet.

Yeah, exactly.

And to Charles’ earlier point, depending on the gravity of where you are, if you did this on a comet or on an asteroid, there are things we throw or hit that would actually go into orbit and would never land.

So you have to check your escape velocities and what the sport is for what you’re doing.

So there’s no little help when that happens.

When your ball leaves the asteroid, just like, oh man, well, game’s over, guys.

Standing on a comet, every single fastball that Jacob deGrasse throws would go into orbit or possibly even escape into deep space.

Okay, that’s cool.

All right, we got time for one more.

Okay, who’s next?

Ryan Gurentz.

Hi, Drs.

Tyson and Liu.

I’m an avid golfer and one of my favorite things to do is golf at high altitude.

So this is an earthbound.

This is here on earth.

We’re back on earth.

Yep, we’re back.

All right, but this is a nice little twist.

At high altitude in Colorado, the ball goes 10% further and is a ton of fun to hit as far as the pros do at sea level.

I have two questions on this.

One, is the ball flying further due to the lower air pressure at higher elevations and therefore less air resistance?

Or is it due to the dryness of the air and lack of humidity that gives less resistance?

Second part of this question, what is the relationship between ball flight and altitude as you go higher?

For instance, if I hit a driver off the top of Mount Everest, could I hit a drive thousands of yards only due to the altitude and not to the fact that the ball flight would be going downhill?

Thank you and can’t wait to hear the answer.

Great question.

Wonderful question.

It also relates to why people in the Colorado Rockies baseball team hit more home runs on average.

However, I will say, if I’m not mistaken, based on what I remember from a previous conversation, when he asked about humidity, humidity makes air less dense, thereby making the ball go farther.

So it wouldn’t…

So what you want is high altitude and high humidity.

And high humidity.

So the drying, the dry air he’s talking about is…

Is not helping…

.

not an impediment, but it’s not helping.

Yeah, but it’s an impediment, but it’s compensated for by just the overall lower air density.

Right.

As you’re getting at a mile high.

Correct.

Do you agree with all that, Charles?

Well, for the most part, yeah.

There are so many different variations, right?

Because the atmosphere is not uniform.

And so you hit a gusher or you hit a particular area of high pressure or low pressure.

You can do that at any altitude.

So generally speaking, you’re correct.

Now the question about altitude overall is very interesting too.

Because like if you do hit a golf ball from Mount Everest, can it go thousands of yards?

Well, it turns out that the atmospheric density on a planet is exponentially decaying.

So for example, from here…

It’s actually reducing when you say decay.

Yes.

It’s going down.

So from here up to say the top of Mauna Kea, which is in Hawaii, the big island where there’s a lot of telescopes, that’s about 4,000 meters.

And the atmosphere there is about 60% of what it is here on the surface of the Earth.

Now, if you go up another 4,000 meters, that is to the top of Mount Everest roughly, then it goes down another 60% from there.

So it’s only about 35%, 36% of the density of sea level.

So that’s why people need oxygen up on Mount Everest because the atmosphere is about 35% of that surface.

But you don’t get like linearly going up so that you might be able to hit the ball a thousand yards if you’re a really good driver.

But I don’t know if you can go thousands of yards because the atmosphere just doesn’t quite drop that fast.

Plus, you can look at what the air resistance is on a golf ball and how much distance it takes off of your shot.

You just remove that air resistance and then you get the full sort of symmetric parabolic shot.

So it’s not going to go up by factors.

Right.

Dimples on a golf ball actually use atmosphere to allow it to float for longer periods of time.

So you may hit some sort of a turning point, right, where you keep getting longer and longer and longer, but then at some point the dimples don’t do their work as well.

Exactly.

And you actually start losing the effectiveness and you can’t hit it quite as far because the atmosphere is too thin.

That’s right.

The dimples have nothing to work on.

Right.

So if we had a golf tournament on the moon, the golf ball’s design would be different.

Exactly.

Yeah, the dimples wouldn’t be relevant.

And curving wouldn’t matter.

You wouldn’t slice a ball.

You wouldn’t hook a ball.

The ball would just go straight from wherever you hit it in whatever direction you went.

So you can’t bend it around a tree.

You can’t give it back.

Well, you could give it backspin.

Well, on contact with the ground.

Yeah.

On contact with the ground, you could give it spin.

That’s about it.

You’d end up playing like a crazy goat.

Lunar crazy goat.

You’d have to hit it off a rock or a surface or a user crater.

Oh, wow.

Now, see, that’s a three-cushion pull shot.

You know what?

That makes sense, though, because it’s only going to go straight.

So if you’re shooting it at a target, then what you could do then is figure out the trajectory from the target in order to get where you want to go on the course.

That’s interesting.

Wow.

Billiards golf.

And so we are people who have time on our hands, and then we go and invent stuff like Giliards.

Guys, we’ve got to take another quick break.

When we come back, more crazy sports, cosmic, geeky questions from our Patreon fan base on StarTalk Sports Edition Cosmograb bag.

We’re back, StarTalk Sports Edition, Cosmic Queries Grab Bag, with my friend and colleague, geek and chief, Charles Liu.

And of course, Gary and Chuck, we got there.

Charles, how do we find you?

What’s your social media footprint these days?

Ah, I am at Chuck Liu, C-H-U-C-K-L-I-U.

My channel is The Luniverse.

That’s like a podcast, and we’re doing a series kind of stuff.

I see what you did there.

Yeah, I know.

I thought it was a little bit cheesy, but everyone around me said, no, it’s the obvious.

I love it.

Yeah, cheesy because the moon is made of cheese or what?

Something like that, yeah.

Now I’m hungry.

Okay, so where do we find your podcast?

Well, it’s on YouTube at the moment, and it’s going to go to different places all around eventually, but it’s a lot of fun.

We talk to younger scientists mostly, where they’re at the cutting edge.

You have to find out about them, not just about their science, but them as people.

It’s beautiful.

And we keep that wheel of education turning from those coming up to those…

The wheel of education keeps turning.

Go.

Thank you, Chuck.

I do know where we’ll be tomorrow, though, Chuck.

Maybe Journey, but I know.

It’s in these wonderful young scientists.

Our future is secure with these guys.

All right, who’s next up with the question?

It wouldn’t be the same.

It wouldn’t be…

Thank you, Chuck.

It wouldn’t be the same without Violetta.

Is she like 30 years old by now?

How old is Violetta?

This child has been asking questions.

I think she was prenatal or something.

All right, so Violetta Rall is now 14.

And 14 goes under the title of astrophysicid.

Yes, that’s awesome.

Astrophysicid?

Yes, that’s very…

Wonderful.

Will we ever reach a point in the near future of sports when it will not be physically possible for any more world records to be broken?

If so, which sports do you predict might get to this point first and how far might we be from this happening?

Also, would we even know?

I mean, the human body can only be pushed so far?

Question mark.

And I need the science on this.

Thank you.

You’re welcome.

And she’s a big fan of the show, as I think we all understand.

We had a show on this one time about prosthetics, aiding sports.

And if you reach the limits of the human body, would people still come out to see the sport if no one is capable of beating a world record?

And then we said, well, just add extra stuff.

You do stuff.

And then, for me, the best answer to that was, in the limit, then you’re just seeing robots compete.

And that’s not the same thing as seeing humans.

The human gets all the joints replaced by robotic assistance.

So, Charles, what do you think of that question?

Yeah, I agree with that statement.

It all depends on the rules of each game.

Rules of each sport.

For example, if you’re playing a sport today, you’re allowed to wear certain kinds of equipment.

You’re allowed to use certain kinds of tools.

But you are not allowed to use certain other kinds.

If you have a bat, for example, you’re swinging baseball with, you can use a wooden bat, but you can’t use an aluminum bat.

You can have some pine tar on it, but only a certain amount of it.

Depending on the rules of the game, if the rules keep changing, then world records will be able to be set without limit.

Provided they’re changing in the favor of performance.

Prius, that’s right.

Like we were just saying earlier, as Javelins get heavier, there’s only so far you can throw them, right?

So it really depends on that.

So as far as humans are concerned, I feel like weightlifting is one of the most important ways that we can measure the limits of humanity, right?

What are weightlifters allowed to do?

What are they allowed to use?

What techniques, the chalk, the grip, the gloves, the body has a limit.

And then people will push the body by adding different kinds of training regimens.

Perhaps if they wish not to follow the rules, they might add certain chemicals, but then those chemicals are banned or not banned.

So it really depends on how much and what you are allowed to do that will determine the limits.

But I’m pretty sure that at some point weightlifting is going to be limited.

Unless you allow robots.

Is weightlifting going to be the first one that we are going to see this limit?

In my opinion, right off the top of my head, I think weightlifting will be the first one.

Yeah, but you know, when you think about it, speed, our physiology, there is a speed limit for us as human beings.

So it’s the same as in, you know, you are looking at strength.

It’s like our muscles can only do so much.

And then of course, if you were able to exceed it, then there is like immediate ramifications for doing so in the body.

So that’s another, you know.

So, you know, I’m looking at something like a microchip that might be able to perhaps increase like either the response times between your twitch, but then allow you to exceed that and not actually suffer damage.

Like those type of things can also, you know, make us go past our speed limit.

So the other thing is, the other thing Charles, we had Usain Bolt come along and destroy 100m world record, right?

Now that caught everybody by surprise.

What’s to say someone with a very different body shape to the classic sprinter shape comes along and destroys Usain Bolt’s records?

What then?

If I destroy though, Gary, it’s only by a few tenths of a second.

I was going to get there.

So just to be clear people, I think I first saw, I first noticed this in swimming where they have touch pads that records your arrival time at the end of the race.

It might be that the future of world records is in the next decimal place.

So that we peg ourselves at some number of minutes or seconds and then tenths of a second, then you go to a hundredths, then maybe thousands and then tenths of thousands.

And the whole contest might be contested in that added decimal place that we need in order to see what the world record would be.

When my father ran track, it was four people at the finish line with a manual stopwatch and they would click it when they saw three people for each lane and they would throw out the high and the low and they’d use the middle score and they’re reading tenths of a second.

So you would know Usain Bolt would win, but you wouldn’t be able to measure how much he won.

So it’s accuracy and time keeping.

How you measure it.

So the other thing here is, you swimming and use the 100m sprint, it’s not the fact that you run the time, then you now change a metric of saying, I did it with less strides, I did it with less strokes.

If it’s a high jump, I took less steps to get to my jump and then clear the bar.

So if we’re getting a stale part of world record and it’s not being broken, do we look at other parts of the event to look to see as that as categories of judgment and then I broke the world record with only so many strides in the 100m?

Are we looking at maneuvering in that way?

I think what’s more interesting than what you just said, Gary, is the fact that when you have people who have a different physiology enter a sport, more people like that enter the sport.

So Usain Bolt is this lanky, long-legged.

He’s not just lanky, he’s long-legged.

And he doesn’t even look like he’s trying.

But if you think about the history of that sport, not a lot of guys looked like him.

A lot of sprinters were actually short.

And by the way, right in this moment, I’m looking at a run of records of the last 12 world records for the 100 meters.

And just to be clear, we say Bolt shattered the record.

He beat it by one tenth of a second.

That’s a lot.

It’s a lot compared to other increments on the world record.

But in the big picture, it’s still a tenth of a second.

So what I’m saying though is, imagine how many lanky Jamaican kids right now are running sprints because of Usain Bolt.

Imagine how many gangly kids are swimming because of Phelps.

Totally correct.

When you look at basketball, think about the origins of basketball.

Let’s be honest.

You look at those old films, it’s a bunch of short white guys hanging around and then going for a cigarette afterwards.

You know?

I mean, you look at the sport today, a guy who’s 6’2, is considered small.

There are all manner of body types out there, not all of which were imagined to excel in sports.

My father’s among them.

I’ll retell that story right now.

Where he was in his high school gym class, and they’re changing units, and they say, we’re now going to go to track and field unit.

They pointed to my father online and said, Cyril Tyson right there, everyone look at him.

He does not have the kind of body that would make a good track and field athlete.

He said at age 15, no one is going to tell me what I can’t do with my life.

He took up track and field from then on.

He became world class, had the fifth fastest time in the world for his event, which was the, it’s not run anymore, but it’s the 600 yard run.

And so, but anyhow, just body types and things, maybe one body type is good for it.

Maybe others don’t know they could be good for it, because you have other people, other idiots telling you no.

So yeah, I agree.

I agree all around.

Inclusive.

I think we answered that question.

Sorry, sorry, Violetta.

Yeah, we ran away with that one.

It’s just a testament to our great questions.

Here we go.

I’ve got one here, and we’re going to throw it into the near future.

Alejandro Reynoso from Monterrey in Mexico.

With the FIFA Football World Cup coming up in Qatar in November and December of 2022, how do we think this will affect the abilities of the player?

In 20…

Okay, high temperature, low humidity.

What are we talking about?

With Qatar, we’re blessed, because normally the World Cup is a summer event, which would be brutal just to watch the thing take place, let alone play.

Didn’t they move just for that?

Yes, they moved it to November, December.

So the thing is, in November, checking this out, they have about an average temperature of 85 degrees Fahrenheit, and a humidity level of average 66%.

The heat index, you’re going to like this, 91.4% Fahrenheit.

But don’t forget, all of these heat indexes are measured in the shade with a light breeze.

So if you’re stuck in the direct sunlight, right, and there’s no wind, you’re going to cook.

Now, adding to that…

Just to be clear, in midsummer, July, in Qatar, it’s 105 degrees average high temperature.

In the month they’re going to be playing, what is the average high?

85, 86, right?

So it’s across November and December.

So the thing is, if you’re in direct sunlight and you actually happen to be exercising, which would be a surprise for a footballer in the World Cup, you can add another 15 degrees Fahrenheit to the heat index.

So the heat index is going to be about 106 for an athlete in the World Cup.

Now, if you drag it into December, the temperatures go down to about 75 degrees Fahrenheit.

However, the humidity levels go up to 71% average.

So you’ve got that little kicker coming in.

You lose a little bit to that.

So either way you slice it, it’s going to be uncomfortable.

These heat indexes are based on people who are in the shade, like I said, with a nice breeze.

These are footballers that are out in the stadium.

The surface temperature on the field will be close to 100 degrees because it just sits and bakes.

There’s not much breeze to cool the surface.

Now, you’re in Doha, which is quite a populated urban city, so there’s not much chance of a lot of breeze in there.

So it’s going to be a very, very challenging environment.

And I think the teams, the organizers, FIFA, are going to have to look at hydration breaks during either half.

You’re going to have to look at…

A lapped break in soccer?

There’s no breaks in soccer!

There never used to be.

You were lucky you got half time.

And so they’re going to take hydration breaks.

They’re going to have to look at development of a larger squad.

So they’ll increase the number of substitutions that take place.

So the stadium is open air?

Yeah, generally.

I mean, unless they’ve built some…

Let’s hope to God they haven’t because the amount of energy it takes to cool a structure like that is ridiculous.

And part of the reason why it’s untenable to play there in the first place is due to the warming planet.

And let’s not make things worse by figuring out how we can cool things off to play.

Here’s a real suggestion.

Don’t play sports in the frickin desert.

How about that?

See, the thing is all those numbers I’ve just relayed are averages.

Now, we’ve had a bit of a sizzling summer in 2022, and so has the rest of the world.

If there is some kind of heat wave, you can bump those numbers right up.

So, let’s be mindful of this is a challenging environment.

And I’m sure what we’ll do is we’ll find medical teams from each country that are participating will have spotters looking at their players.

They’ll all have some sort of GPS, biometric, biometric data, biodata coming back.

For hydration and everything.

Yeah.

As dramatic as soccer players are.

My knee, my knee.

I need a drink.

I can’t believe I have the vapors.

It’s my fainting couch.

I’m in my fainting couch.

Oh dear.

So terribly, terribly warm.

Chuck, you have just made the World Cup so bloody interesting to watch.

All right, guys, we got to end it there.

This has been fun.

Charles, it’s always great to get you back in the house.

It is great to be here.

Thank you so much for having me.

And good to learn of your podcast.

Tell me the clever name again.

The Luniverse.

The L-I-U-N-I-V-E-R-E-S.

The L-I-U-N-I-V-E-R-E-S.

As in Charles’ L-U-N-I-V-E-R-E-S.

See what you did there.

Well, again, I didn’t do it.

People around me did.

But I’ll accept it.

We got it.

It was a good choice.

Chuck, it was good to have you, man.

Always a pleasure.

Gary, love you, man.

Love you too.

This has been StarTalk Sports Edition Cosmic Queries Grab Bag.

I’m Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, as always, bidding you to keep looking up.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron