About This Episode

On this episode of StarTalk Radio, Neil deGrasse Tyson explores the mysterious, dangerous, and possibly life-harboring world of comets and asteroids. Joining him is cosmochemist and science communicator Natalie Starkey, PhD, and first-time comic co-host Mark Normand to answer questions submitted by our fans on social media.-.

To start us off, Natalie explains the classical differences between comets and asteroids. You’ll learn if it’s possible to hollow out an asteroid to create a star shield. We explore the benefits and drawbacks of asteroid mining. Would mining a comet change its orbit? Discover more about the “worth” of a comet and why any large influx of materials from a comet could collapse economic markets and industry.

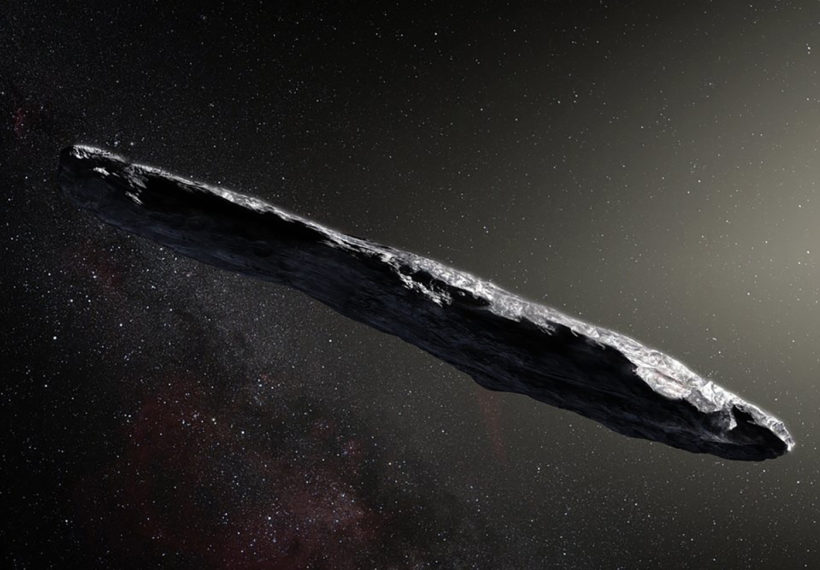

You’ll find out why comets can be different colors, and why some glow green. We discuss the cutting edge technology that allows us to track where asteroids originally came from. You’ll also learn more about ‘Oumuamua, the interstellar visitor that passed through our solar system in 2017. We discuss if there are points between stars where comets are free from the influence of gravity. Neil shares his memories watching Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 collide with Jupiter.

Investigate where the water on Earth originally might have come from in the early formation of the planet. We debate the Panspermia hypothesis and try and gauge what the survivability of tardigrades means for transporting life across the universe. You’ll also hear about the Oort cloud. Mark wonders why we don’t get hit with asteroids more often and Neil and Natalie describe how the Earth is constantly plowing through space debris. Lastly, Natalie refreshes our memory on the Chelyabinsk meteor that struck in 2013. All that, plus, Neil and Natalie explain why studying comets and asteroids may hold the answers to one of the most important questions of all – how did we get here?

NOTE: All-Access subscribers can watch or listen to this entire episode commercial-free here: Cosmic Queries – Asteroids and Comets.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTFrom the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, and beaming out across all of space and time.

This is StarTalk.

I’m your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, and today is a Cosmic Queries edition of StarTalk.

And I’ve got with me co-host, Mark Normand.

Mark.

Nice.

The first timer.

Hey, hey, big fan, happy to be here, thank you.

Your local New Yorker?

Local, got lost in the museum like an idiot.

If you have to get lost anywhere, let it be the American Museum of Natural History.

That’s true.

In the day.

Yes, oh, that would be terrifying.

You don’t wanna get lost at night.

No, sadly, I was using my night at the museum knowledge.

I’ve seen the movie.

Using your coordinate system from that movie to avoid, no, but you got here in one piece, which is excellent.

Today’s topic is comets and asteroids.

And I know a little something about it, but I don’t know as much as I should know about it to carry this episode alone.

So we went in for backup.

Nice.

Backup.

And there’s a good friend of ours who’s been a guest before, Natalie Starkey.

Natalie, welcome back to StarTalk.

Hi, Neil.

It’s great to be here.

Thanks for having me.

We’ve got you online.

You are in-

No, she’s on Mars, actually.

No, no, so we’ve got her.

You’re in the UK right now, is that correct?

Yes, yes, I am.

I was over in California for about three years, living over there, and now I’m back in the UK.

So I’m getting used to the rain again and the cold, and I’m very miserable.

We got spoiled that you were so accessible to us over those three years, forgetting that you’re basically a UK person.

So there it is, you’re officially a science communicator.

That’s like a title that you carry for the Open University just outside of London, right?

Yes, that’s correct, yes.

So I’ve been a scientific researcher for about 10 or 11 years, and then I got into writing, and I love communicating the science that I do.

So yeah, I’m getting into it more seriously now.

So I’ve sort of like, I’ve got a serious science background.

I know quite a bit about comets and asteroids, so hopefully I can be of use today, I’m hoping, fingers crossed.

So we’ve got, and I happen to have, I think what is your latest book, called Catching Stardust.

Yes.

Comets, asteroids and the birth of the solar system, I have it in my lap.

I’m gonna hold it up for the camera for those people who are watching.

I had to do a bit of product placement, you know.

Exactly, exactly, but you gotta come back one day and sign it.

Definitely.

So we called questions from our fan base on this topic of comets and asteroids.

And so let’s see what you got.

Neither she nor I have seen these questions.

So let’s check them out.

Okay.

It’s kind of nerve-wracking.

I’m a bit worried.

I hate having my knowledge tested.

We’ll see how it goes.

If you don’t know, just say, I have no freaking idea.

Go on to the next question, right, okay.

All right, these are pretty good.

I’ve read a few and I’m gonna go handpick.

All right, this first one’s from Kyle Ryan Toth.

He’s a Patreon member.

Patreon, we got to serve them first, apparently, yeah.

Exactly.

Would it really be possible to hollow out an asteroid and use it as a starship?

Cool.

Natalie, how about that one?

Okay, so I’m gonna say no straight off just to be really boring, but actually one of the reasons we couldn’t really do this, well, with most asteroids anyway, is that they’re either just too hard or they’re just not made of the right stuff.

So we’ve got some asteroids that are made completely of metal.

So I mean, trying to hollow that out would be almost impossible.

We’ve talked about mining these in the past and we talked about them on the show quite a bit and it’s incredibly difficult to do that.

So I think mining a pure metal asteroid would be hard.

And then the others that are made of, they could be slightly softer.

We described some of them as a bit of a rubble pile.

So they’re kind of just rock that’s not very well consolidated, not very well pushed together.

So that would basically break up as soon as you try to start excavating it in any way.

So you’d have a better chance maybe living on the surface.

But I think even then, there’s no gravity essentially.

So they’re kind of hard beasts to work with.

I don’t think we’re gonna live inside one.

So they’re very low gravity.

They have some gravity, right?

They do, they do have a little bit.

But basically you would need to be tethered onto the surface of one.

If maybe we went to the largest asteroid in the asteroid belt, which is Ceres, it’s about 1,000 kilometers across.

Wow.

So it’s gonna have a little bit of gravity, but if you jumped too high, you would probably just end up floating off into space.

So it’s not gonna be a great environment to try and live on, or in, rather.

So I think the lesson there is just make your own damn spaceship.

Yeah, but could you get a rudder on there?

I mean, could you steer?

You know what I mean?

I feel like you wouldn’t get any directionality.

Oh, you mean if it’s just a hollowed out orb.

Yeah, you’d need some kind of retro rockets affixed to the side of it so that you can maneuver.

Exactly.

Rather than just like a homeless shelter inside a shell.

Yeah, I don’t know what they were thinking of with that question.

Yeah, yeah, I mean, it’s a fun thought.

All right, let me throw to this guy.

All right, go for it.

Kyle, you blew it.

No, just kidding.

Nice job, Kyle.

He’s smoking weed.

This is kids’ disobvious.

We just lost one Patreon member there.

I’ll cover him.

All right.

This is from Michael Halterman.

Can comets have different colors?

Diversity.

Maybe when the ingredients in organic molecules are different, can they spread molecules for the beginning of life?

Yeah, okay, so that’s sort of two questions there.

So the first bit was about the colors of them.

And yeah, for sure, when we see comets in the night sky, they can glow different colors.

And actually green is a really common color when we look at these objects for various reasons.

And when we look at a comet or an asteroid maybe in the night sky with a telescope, then they can glow green because of the oxygen that’s in them.

But actually, sometimes if you see a meteor coming through, so basically if you get a little bit of an asteroid break off in the space and then head to the earth, and you see that as a fireball in the night sky, sometimes they can glow green.

And that’s for different reasons.

So that’s because we have basically nickel, which is burning up.

So I mentioned that we had these metal asteroids earlier.

And nickel is one of the metals that they have in them.

And actually, when that burns up in the atmosphere, that glows green.

So sometimes you see this kind of green streak with a meteor.

You’re quite lucky if you see it.

I’ve never actually seen it.

But I know people talk about it.

And so that’s the nickel kind of burning up.

So yes, they definitely have different colors.

What was the second part of that question?

I’ve forgotten already.

This is not good.

Life, whether the ingredients within the tail of a comet are the right ones to possibly spawn life.

Yeah, okay, definitely.

So this has been quite a recent research finding actually that we’ve discovered with some of the recent missions to comets, so in particular, the European Space Agency sent the Rosetta mission to go and land on the surface of a comet back in 2014 now.

And they discovered that there was actually glycine, which is an amino acid within the comet.

So we know there’s basically these complex carbon molecules within them.

And so there’s every chance that, you know, they have the right ingredients for life.

And this is why we sort of say, well, you know, in the past, we think earth was bombarded by comets and asteroids from space.

And so it’s a plausible way that we could have brought life and water to earth, because we know that these objects contain a lot of these ingredients.

And we know that asteroids contain hundreds of amino acids.

So these objects in space, they’re very old, they’re very, what we call primitive.

They’re some of the earliest things that formed in the solar system.

But they contain all the ingredients that you need to basically build a planet and build life on that planet.

So this is why I find them such fascinating objects, because they have everything we need.

And that would mean that life, based on what you just said, life could be vastly more common in the universe than people might have previously suspected.

Yeah, so the problem is there’s a bit of a leap from going from just having the amino acids and the basic carbon compounds and the molecules to then getting life, okay?

So that’s a massive leap, because the problem is we might have all these ingredients in space everywhere.

In fact, they might be in every solar system we care to look at.

But the problem is it doesn’t mean that we’ve got life, because we need some very special conditions to let those ingredients become life.

It isn’t just a simple step, so.

We think they’re special conditions, maybe they’re common.

Well, this is very true.

We have only so far observed life once, and that is on Earth.

But it doesn’t mean that in the hundreds of billions of galaxies that are out there on all the stars that there isn’t life somewhere else.

We just haven’t seen it yet.

Now, obviously, we don’t actually know there’s not other life in our own solar system.

We just haven’t seen it.

But we’re pretty sure it doesn’t exist on the terrestrial planets, the ones that are near to, these are the rocky ones near to the sun, like Mercury, Venus and Mars.

Maybe they had life in the past.

We haven’t discovered that yet.

But there is a chance that there is life on some of these weird moons, like Europa and Enceladus and things.

So we’re not sure yet, but there’s a chance it could be, because they’ve got a lot of the right ingredients for life.

They’ve got liquid water.

They’ve got, basically, their energetic bodies.

They’ve got heat that they’re losing.

So they have all the energy that they could create life and help it get along and move along.

So we just haven’t found it yet.

We need to go and look.

We need some missions to go and look at these places in more detail, but they’re challenging environments to send spacecraft to.

So that’s one of our problems at the moment.

As Frankenstein knew, Dr.

Frankenstein, you can’t just have the raw ingredients.

You need energy.

Right.

And he had like that lightning bolt going through the electrodes on the neck.

Yes.

See, that’s all it takes.

That’s it.

Wow, well, that was well done.

Yo, thank you, Natalie.

Natalie, that killed it.

Let’s see, well done.

Also, nickel, I didn’t know about.

That’s fascinating.

No, nickel, please.

You know who knows about nickel?

The Gucci brothers for the fireworks.

There’s all these metals that get burned in fireworks that give you all the beautiful colors.

Oh, I didn’t know that.

Nickel, copper.

What else do they have in there?

Magnesium, I think, Natalie?

Yeah, yeah, I think that’s a good, yeah.

So basically, it’s a bit like doing that flame test.

You might have done that in chemistry labs at school.

Basically, it’s the same principles.

Each element burns with a different color.

But basically, this is the principles, yeah, of fireworks and everything.

And what we see burning up from each is, we could tell a lot about what that asteroid was made of if we can see it glowing.

So, yeah, it’s fascinating.

All right, this is all news to be.

Here’s another one from Ashley VGT.

This is off Instagram, I’ve read that water did not originate on Earth, but instead was introduced by asteroids.

But wouldn’t the water evaporate away upon entering the atmosphere?

Ooh, burn up.

Burn up.

Coming in.

So what’s up with that Natalie?

So the whole water on Earth thing is definitely a big open debate still.

Scientists currently really don’t have a good consensus on where our water came from.

So the problem is if Earth started with all its water from the beginning, so our planet is about 4.5 billion years old, it was born out of this cloud of gas and dust, really close to the sun.

And we think that that early cloud contained water because if we go into interstellar space where all our solar systems are made from, sure enough, there is water out there as ice, of course, because it’s very cold.

And now that gets kind of swept up into the forming star and then all the planets are born out of the cloud of gas and dust that is around that star.

So there’s water ice there that could then be contained within the planets that we form.

But the problem is the very first few million slash billion years of a planet’s infancy, it’s incredibly hot.

So it’s basically just like a volcanic world.

It really wouldn’t be able to support a lot of water unless the water was sequestered away very deep within the planet maybe and it didn’t evaporate at the surface.

So we’re not sure whether we could have from the beginning had our water or whether sure enough it would have all boiled off during that process.

And then we needed to bring it in later on.

And we know we were bombarded by comets and asteroids about four billion years ago.

We just have to look at the surface of the moon for that actually, because you see that beautiful cratered surface of the moon.

And actually we were hit by as many things as the moon was hit by, but we have this thing called plate tectonics where our surface gets continually changed and updated and resurfaced.

So we’ve lost all that evidence of all those craters, whereas the moons preserve them for us.

So we know that we were hit in the past.

And sure enough, those comets and asteroids contained water, some of them did anyway, not all of them.

And they could, if they were large enough and they didn’t evaporate and explode completely on reentry through the atmosphere.

And remember our atmosphere was quite different back in the day.

In fact, we might have had much of a thinner atmosphere that didn’t slow them down as much.

Then potentially, they could have bought a lot of water with them.

But for us, trying to figure out where the water came from is very, very tricky, because we need to find out what the water looks like.

And it’s all mixed up now.

We’ve got a mixture of all these different types of water.

So if we want to measure it now, it’s very complicated to try and figure out exactly where it came from.

And all the comets are different, all the asteroids are different.

So we need to just go out there and measure more of these objects.

So then try and kind of piece this story together.

But it’s important because we want to understand why water is here.

Why are we the only planet in our solar system with liquid water at the surface?

It’s a question that we really want to answer to understand where life came from as well.

So that was a yes.

It’s one of my favorite subjects.

Okay, that was clear.

Yeah, this is from DonnieHuss1130 from Instagram.

It’s like a comedian.

Ooh.

But let’s sharpen that and say, of the metallic asteroids that have metals we care about, can you estimate the value of them?

And what does the value mean if they’re out there versus if we brought them back to Earth and now they’re just on Earth?

Like, value is just, value is a flexible thing in this, right?

Exactly.

It’s sort of like the diamond issue.

Like, there’s plenty of diamonds on Earth.

We combine plenty of them, and actually a lot of them have been mined.

But then the diamond market is controlled because if we released all those diamonds onto the market in one go, we’d flood the market and the price would drop.

So, you know, the big diamond companies don’t want that to happen.

So they control that market.

So it’s sort of the same thing with these asteroids.

One asteroid, OK, so there’s a mission, a NASA mission, actually going to an asteroid called 16 Psyche.

And it’s made purely of metal.

We don’t understand a lot about this asteroid, but it’s quite large.

And actually the team that are planning to go to this asteroid have estimated that it’s worth $10,000 quadrillion.

So and that’s just the iron within that.

So basically, if they were to mine that whole asteroid, which would be impossible because it’s too large at the moment.

We have no way of doing this at the moment.

But if we were to be able to figure that out and we brought all of that metal back to Earth, then sure enough, we’re going to flood the market and it wouldn’t just kill the metal market, it would kill the entire economy because we wouldn’t know what to do with all this.

So they’re worth a lot, but one of the issues is we don’t really know how to currently mine them.

We don’t know how we would extract that metal and we don’t necessarily want to bring it back to the planet, to be quite honest.

We would like to bring some back, but actually one of the reasons we want to mine in space is to be able to further explore space itself.

So we could use these materials to actually make things.

So we might have a base on the moon where we actually manufactured materials and spacecraft or whatever we needed and tools to actually go and explore further into space.

So there’s a lot of economical questions around mining asteroids.

It’s not just the science of how we do it.

It’s then looking at how it works and what we’re going to do with the materials that we get.

Mm-hmm.

Rebuttal?

No.

It’s funny to just assign a value to something which if you obtained it would not have that value.

Yes.

Exactly.

It means nothing really, but yeah.

It’s a weird economic fact of this.

I never would have thought you could get money out of an asteroid.

Plus, iron is not uncommon on Earth.

So I’m thinking, Natalie, that if you are going to bring a metal from an asteroid to Earth, you bring a rare metal that we can use in ways that we can’t do now.

If you bring all that iron, is there something else you’re going to do with iron that we’re not already doing with iron?

No, so that’s the thing.

And the thing about these asteroids is, okay, they contain a lot of iron, but they contain maybe less than a percent of precious metals.

Things like platinum and gold and these metals that we use in technology is a lot in the modern day.

Now the thing is they contain very low percentage of these, but that is still a lot more of these precious metals than we mine in any one year on our own planet.

Because the thing is about the precious metals on Earth is that they’re distributed throughout the crust of the Earth and they’re not very well concentrated.

So to mine them, it takes a lot of effort.

We have to dig up a lot of land in order to get those metals.

Whereas if we just went to an asteroid, they’re a lot easier to obtain.

They’re sort of concentrated in these objects.

So these are the metals that are really important because at the moment we don’t have a continued infinite supply.

So the kinds of industrial technologies we’re looking at and the advanced technologies we want to develop are sort of held back a bit by the fact we don’t have this infinite supply of some of these precious metals.

I think that’s the key point because it’s not that you’re just going to sell the metal and someone is going to then make jewelry out of it or something.

There’s industry that uses metal.

Yes.

So it enables, no matter the price, it enables certain industries that wouldn’t otherwise be enabled.

Perhaps we shouldn’t think of it just as the metal as a pure thing, but the metal as an enabler of other ideas that engineers would pull out of the box.

We got to take a break.

Mark, you’re still here?

Oh, yeah.

Dr.

Natalie Starkey, still there?

Out there outside of London.

Thanks for piping in.

We are talking about asteroids and comets on this Cosmic Queries edition of StarTalk.

We’ll see you in a moment.

Bye Unlocking the secrets of your world, and everything orbiting around it.

This is StarTalk.

StarTalk, we’re back, Cosmic Queries edition.

Mark Normand.

Oh yeah.

First timer.

Oh yeah, love it here.

We’re watching you, first timer.

Dr.

Natalie Starkey, you still there with us?

Yes, I’m still there.

Excellent.

Yes.

Expert on comets and asteroids, and that’s our topic for the day.

Yeah.

I know a little bit, and she knows a lot.

Oh yeah.

That’s why we brought her on for this episode.

So Mark.

You’ve got questions on this?

I got a million, let me just, well, when we talk about the nickel and the iron, if-

You got a question too.

You can do it too.

I just wonder if-

He’s feeling it.

He’s feeling it.

If asteroids contain diamonds and we mined them and we got the diamonds and diamond prices went way down on earth, would women still want them?

I mean, the thing is they do contain diamonds, but they’re actually even more special than the diamonds we have on earth.

So they’re actually sort of like interstellar diamonds.

They’re older than our solar system.

But they’re tiny.

This is the problem.

So they’re kind of hard to find.

So you probably wouldn’t, you’d need a microscope to actually see it on your ring finger.

But you could tell everyone how special it was.

You can’t see it, but it’s interstellar.

Here we are.

kimberly.io on Instagram, underscore kimberly.io.

We actually had, well, we don’t really know if it’s an asteroid or a comet, but there was an object recently called a Muamua, which is a Hawaiian word for basically kind of like a foreign traveler or something.

And it’s this object that appeared and it was traveling very fast through our solar system.

And some astronomers in Hawaii saw it and found it first, and that’s why it got a Hawaiian name.

And it was traveling so fast that they figured out it couldn’t have come, it couldn’t have originated within our solar system.

So they actually decided that it must have come from another star system somewhere.

They have no idea where exactly they’re still trying to figure that out.

But basically it didn’t, it was going so fast, it didn’t get captured to our sun.

So it just kind of scooted by.

So it didn’t enter into orbit into our solar system.

And this object has probably been traveling for potentially billions of years across interstellar space.

We don’t know if we’re the only solar system it’s traveled through, but it’s going on this massive long journey.

Now, of course, this object could have actually collided with the planet and we wouldn’t have seen it coming because it was going so quickly and it was relatively small.

It was very dark.

So really, really hard to spot.

But the thing we realize now is that we’ve spotted it because our technology has got so much better at trying to spot things in the night sky.

It’s actually probably happened before.

Probably we’ve had these visitors from other parts of the galaxy many times before, but we’ve just not seen them.

And sure enough, our own comets and asteroids could be out there visiting other star systems.

It’s just something that happens during the process of forming a star and the planets around it that is a little bit chaotic.

And so comets and asteroids are essentially the bits and pieces left over that didn’t become a planet.

And sometimes, because they’re small, they can get ejected out of the solar system, or they get thrown into the sun, and they end in a fiery death.

But some of them get thrown out, and they just end up leaving the sun’s gravity, and they go off into space, and then there’s nothing stopping them.

They’re gonna keep going.

So yeah, it’s really cool that we’ve got these objects.

If we can start to identify more of them in the future and actually look for them, then we might be able to launch a mission to go and maybe sample one one day, which would be amazing, because we’ll find out about the chemistry of another star system, which is something that I would be really interested in.

But yeah, at the moment, we’ve only seen one, and it’s kind of gone now.

It’s exiting the solar system, and it’s going on its merry way into the abyss.

Wow.

It’s merry way into the abyss.

That was beautiful, poetic.

I looked up Haumuamua.

I think it means scout, like a first journey person onto a new land, into a new place, a scout.

Yeah.

It’s a nice name, I like it.

Yeah, it is, it is.

Quick question may not be answerable from Paul Pimenta on Facebook.

Can we track where asteroids came from, specifically where they originated?

Yeah, yeah, definitely.

So actually, I mean, it’s even better than that.

Sometimes we get a meteorite that ends up on the planet.

So this is just a rock from space that will usually come from an asteroid, or it can come from another planet.

If we’ve seen that coming through the night sky and burning up through the atmosphere, then there’s lots of basically camera networks out there now.

And one of them is in the deep Australian outback.

And they just basically have cameras set on the night sky to register these objects as they’re coming in.

And what they’re trying to do is figure out an exact trajectory for them so that they can basically backtrack that with some amazing math and actually figure out where that object originated and try and track it back to the asteroid belt itself.

We can sort of check our calculations in a certain way by analyzing the chemistry of those rocks.

So we can go and pick up that rock because basically they know where it’s landed because they’ve got that trajectory coming in on the cameras.

They can go and pick that rock, analyze it in the lab and compare it to what we know about the objects and the asteroid belt already.

So yes, it’s actually possible.

It’s very complicated work and we’re making much more progress with it in probably the last decade or so.

But yeah, we can definitely start to figure out and we also know if it came from another planet.

That’s much easier to work out actually if it came from another planet than any old particular asteroid because there’s kind of billions of them out there.

So it is tricky.

Billions of asteroids, but many fewer planets.

Yeah, there aren’t too many planets.

But there’s probably like maybe two billion asteroids of over a kilometer in the asteroid belt.

So there’s an awful lot of them and there’s millions more smaller ones.

So there are a lot of objects out there.

But a lot of them, as we said, they’re in these groups, they’re in families.

They’re all different.

They all, there are groups that share similarities and where they were made and what they contain.

It’s like a 23andMe for an asteroid.

There it is.

So you meet an asteroid, he goes, I’m Jewish.

Who knew?

All right.

How large, those from Renee Douglas, Patreon, listen up.

How large does a captured asteroid need to be in order to be called a moon?

And can a comet also be captured?

Yeah, so the first part, I mean, in fact, it depends what you call it as a moon really, because some of the asteroids themselves have moons around them.

We’ve actually started to discover, I think we’ve found about 200 moons around asteroids now.

So these are just small objects orbiting and basically attached to that asteroid in some way.

They’re associated with it.

Now the thing about the asteroids themselves is that even the largest asteroid we know of, which is Ceres, is only about a quarter the size of our moon.

So even the biggest one, and even if you pack them all together, so you take all the asteroids in the asteroid belt and put them all together in one blob, they would only be about 4% of the mass of the moon.

So there’s a lot of them out there, but they’re just not very big.

So if you wanted to capture an asteroid, well, you wouldn’t be capturing one of the largest ones because there’s sort of like, you know, thousands, well, hundreds of kilometers in diameter.

So they’re just too large to capture.

When NASA have actually done some studies looking at potentially capturing an asteroid with sort of a bag or something, it sounds kind of crazy, but that’s literally what they’re sort of planning or a scoop.

And they’re looking at something around 40 meters.

So it’s not gonna be particularly massive and it’s not gonna pose a problem to Earth if it goes very wrong, although that would still be an issue if that collided with the planet.

So yeah, in terms of capturing them, you wouldn’t capture something really massive because I mean, if it went wrong, you’d be really in trouble if that collided with Earth.

Wow, this is all, how have we not had more of that?

Why?

I mean, I don’t know anything and I’m on Mali right now, but why don’t we get hit by more asteroids and realize it and feel it?

Well, we do get hit.

Earth plows through, Natalie, correct me if I’m wrong, several hundred tons of meteor dust a day descend on Earth just by plowing through interplanetary space.

And does it make a dent?

No, most of it just settles as dust because it lost all its energy coming through the atmosphere.

But it’s big enough that it’ll just plow right through.

Yeah, there’s like a sideways relationship, an inverse relationship.

So the bigger the asteroid that’s heading for the planet or it’s gonna come through the atmosphere, the less frequently it hits.

So the really small pieces of dust, they’re literally raining down all the time.

And they’re called micrometeorites or basically star dust.

And then as you go to the larger objects, like the ones that killed off the dinosaurs, for example, then they don’t hit very frequently, every 10,000, maybe 1 million years or more, probably more in fact for ones that size.

We had an event in Russia back in 2013, it was called Chelyabinsk and it was about a 20 meter asteroid.

So it’s fairly large, I guess kind of like a double decker bus and that didn’t actually kill anybody, but it did cause quite a lot of damage in the region and it had this big sonic boom as it came through the atmosphere and actually it blew windows and everything in Chelyabinsk town.

And we didn’t know that was coming because it was actually quite small.

We didn’t see it.

We hadn’t spotted it before it arrived.

So, yes, they happen.

And obviously if that had hit Central London, I’m pretty close to Central London, that’s about 60 miles across maybe if you take Greater London into account.

And actually that would be quite an issue if that had landed in the center of London.

So it’s sort of lucky that most of the planet is sort of empty and a lot of these asteroids tend to land in the ocean, so we don’t see them and they don’t cause us any harm.

But yeah, they do hit all the time.

And just the larger ones not as often.

Well, if you’re going to hit somewhere, I think Russia is the place.

Is that a political statement or a geographic statement?

Wow, I don’t know anything about collusion.

It’s the country with the largest landmass.

Good, that’s what I was saying.

So it’s going to get more asteroids and more comet collisions.

But that’s what they get for conquering.

You conquer, you got to realize, hey, you’re going to hit more asteroids.

There you go.

Hits.

All right.

What else you get?

Here we go, Natalie.

This is from Frank Kane, Patreon member out of Orlando, Florida.

Is there a really clear distinction between comets and asteroids?

I mean, comets generally have some rock in them and asteroids have a lot of frozen gas in them, right?

Where do we draw the line?

Yeah, the other way around.

So the asteroids are kind of the rocky, hard, metallic ones, classically.

And then the comets are sort of the icy, dusty, dusty snowballs or whatever you want to call them.

But yeah, this sort of works.

It’s a pretty like old distinction that we always fall back on, but it’s a very classical view of these objects.

And actually what we’re finding as we go and look at more and more of them is that we’ve got a lot of asteroids that can contain quite a lot of water ice and other icers like methane and things.

And we have some comets that are completely dry because for example, if they’ve been around the sun a lot of times and they’ve been basically having their volatile icers burn off all the time, then they’re going to be dry and they sort of look there for like an asteroid.

So there’s a lot of, there’s almost like a continuum, we think potentially there’s a continuum of compositions.

We’ve got some things that definitely look like this classical asteroid, some things that definitely look like a comet that’s very icy and then a lot of material in between.

And at the moment, we’re still trying to piece together that story of basically where these objects formed and therefore what they’re then made of today.

And they’ve also been affected by what they’ve gone through in that 4.6 billion year history since they formed.

So yeah, basically we have that distinction but it doesn’t always work.

But we have yet to see a metallic comet.

True, but they do, yeah, that’s very true.

I mean, if you had a purely metal object out there, then it’s definitely an asteroid.

In fact, this 16 Psyche asteroid that they want to go and look at, they think could be the center of a planet that was kind of blown to pieces at some point in the past when it might maybe collide with another asteroid.

So it had basically in the earth, we’ve got this metallic core.

And that’s what happens to these large objects in the solar system, they differentiate.

So they’re a big ball of magma.

And then the heavy material in that magma, the metal falls to the middle of the planet and the lighter stuff is on the outside.

So if they experience an impact, all of this, what we call the crust and the mantle, which is the lighter stuff on the planet, it gets kind of blown off the surface and you get left with this solid core, which is very hard to break up.

So that’s what we think.

That’s one theory of what this asteroid could be.

So we can study it to actually look at the core of a planet, which is incredibly hard to do because we can’t drill to the core of a planet.

So these objects are really valuable scientifically for that reason.

How come…

Could we film them and watch them hit each other?

I feel like that’d be a great pay-per-view.

Be cool, very cool pay-per-view.

You could bet on them, like with the mob.

I got Haley.

We did have a collision where there was a comet that was predicted to, and of course, successfully collided with, because it was predicted to do so, the planet Jupiter.

And we caught it on Hubble Telescope and everything.

Hey.

Oh, it was amazing.

Send me the link.

It was amazing.

All right, now we’re talking.

And that was a comet that got ripped apart into multiple pieces, so it was like a train of cars coming in, one after another.

And they didn’t all hit the same spot at Jupiter.

You know why?

Jupiter’s big?

No, Jupiter rotates.

So it would rotate a fresh bit of its surface into view, that next piece would hit there.

So by the time everybody hit, there was this line of impact scars in the atmosphere of Jupiter.

It was beautiful.

Beautiful.

Beautiful.

I love it, but how did it…

I just don’t get why it would not burn up in the atmosphere and all that.

We’re seeing the residue of that collision.

I see.

Well, the energy would vaporize the volatiles and it would also vaporize the rocks too, wouldn’t it Natalie?

And there’s a lot of energy.

Yeah, definitely.

It sort of depends, it really just sort of depends what that thing is made of.

So as I said, if we just had a purely kind of fluffy comet that was very icy, so if you imagine just taking a snowball and adding a bit of dirt to it, and then compacting it together a little bit, if that came through our atmosphere or an atmosphere of any planet, it almost certainly would break up very high up and really not cause any damage.

It wouldn’t get to the surface.

But as I said, there’s sort of continuum of composition.

So some of these comets are a bit more rocky.

So actually the more rocky and the more metal components that an object contains, the more likely it is to survive that impact.

Metal, he’s talked to a very high temperature before it’s going to melt or explode.

So this is why it’s hard to predict what’s going to happen.

So actually being able to see that one hitting Jupiter was very informative because we can actually try and figure out what it was made of by the way that it reacted to Jupiter’s atmosphere.

So it’s the same when they are heading to Earth.

If we think one’s coming for us, then we really want to understand what it’s made of and if it’s actually going to pose any risk to us because surely enough, if it was just made of ice, probably it’s not going to be very harmful.

Even if it’s enormous, it’s probably not going to do us any harm.

So yeah, this is why we want to understand them in more detail and understand their composition and their structure as well.

So we got to take a break.

We’ll be back for our third of three segments of Cosmic Queries, Asteroids and Comets Edition with Dr.

Natalie Starkey when we return.

Thank you The future of space and the secrets of our planet revealed.

This is StarTalk.

StarTalk, we’re back, Cosmic Queries, Asteroids and Comets Edition, with our friend and colleague, Natalie Starkey.

Natalie, phoning in from London, outside of London.

We miss you in the States.

We were here for three years, and then you just left us.

I know, I know, I miss California as well, but it’s really far from home, so it’s quite nice to be back in the rain.

I quite enjoy it.

Said no one ever.

She didn’t leave us, she brexited.

Brexited, yes, yes, yes.

So, so.

Oh, sorry, sorry.

So, Mark.

Yo.

My co-host for today, first timer.

What do you have for us?

Here we go.

Let’s go.

Voidwalker92 off Instagram.

Are there any asteroids with their own natural satellites currently known?

If so, how common or uncommon is this, and how does the dynamic affect tracking and understanding trajectory of the asteroid?

Oh, nice.

That makes sense.

Because we addressed a little bit of that earlier.

We definitely know that quite a lot of asteroids have moons, so natural satellites around them, and it’s probably other bits of material of that same asteroid, but we’re not sure, because we haven’t studied them in detail.

One of the problems is that we can’t actually see them very easily, because the asteroids themselves are small, and therefore their moons around them are even smaller.

So we found about, I think it’s over 200 moons around asteroids now.

So we definitely know they’re there.

We want to study them in more detail, because it will tell us more about that object itself and how that object formed.

Do you think those moons dislodged from the asteroid itself to become a moon?

It’s one option, or it could be that they captured them.

So some of the moons that we see around planets are either captured moons, so they’re formed somewhere else in the solar system to that planet, and then basically that planet was large, and so its gravity attracted other objects to it.

Our own moon, for example, didn’t form in that way.

It formed from the Earth itself during a massive collision about four and a half billion years ago, and it basically threw off a bit of our own planet, and then it coalesced into a moon, and it was then, you know, trapped with the Earth.

So there’s different ways to form them, but we need to study more of them to figure out exactly how they formed.

All right.

Next question.

Well said, well said.

Richard Stenhouse from Facebook.

Hi, guys, love the show.

Bit of a kiss-ass.

I’ve been listening on Spotify since September 2018 whilst I’m at work, and I’m as far back as season two.

Can’t get enough.

It’s like a regular Natalie.

Get to it.

Anyway, my question is, is there a point between stars where comets or asteroids are under no influence of gravity at all, and if they somehow lost momentum, would they hang in that space till the end of time from North Wales, UK?

I love it.

Love the question.

That’s a great question.

Oh, my goodness, because I actually only found out recently myself that some of the comets that are in our Oort cloud, which is the cloud of material that’s outside of our, it kind of surrounds our solar system.

So everything in our solar system is on a plane, it’s on a disk, all the planets and all the comets and all the asteroids.

And then we’ve got this Oort cloud around us, which is all these icy objects of which we actually have never really seen any of them because they’re so far away.

And some of them on the edge of that Oort cloud are so far away that they’re almost not gravitationally bound to our own sun.

And they’re almost closer to the next star system.

So sure enough, I don’t know what happens at that point.

I mean, I guess maybe some really clever astrophysicists maybe figure out what is happening to these objects out there.

But yeah, they could easily be perturbed, we would say they might be pushed around by the gravity of another star system.

And then either thrown out of our solar system completely or pushed in so that they actually come in and visit the sun and the inner solar system.

But that’s a great question.

Yeah, they’re susceptible.

Plus we, the sun, the planets and everything, the family, we’re all orbiting the center of the galaxy among other stars.

So even if you have a precariously positioned comet at the edge of this Oort cloud, and it doesn’t have a gravitational allegiance, eventually it will.

Because we’re moving past other stars, somebody’s going to snatch it.

And or perturb it and have it descend back down into our star.

So yeah, the things are always in motion.

And if you’re without allegiance, that wouldn’t be for long.

I’m so jealous.

And just to be clear, Oort is named for a guy named Jan Oort, who is a Dutch astronomer of mid-century, mid-20th century astronomer, who first proposed the existence of this reservoir of comets.

Was he persecuted?

It was all theoretical.

Like, you had no idea it was there, and it’s still not really proven as such, but because we’ve not really seen it.

So it’s just so far away, we’ll never get there.

And even if there’s a spaceship out there now, like Voyager, they are not gonna get there for tens of thousands of years.

So yeah, it’s a tricky one.

Could we get a GoPro on one?

I know, do you think?

Why not?

Plus, this was mid-20th century.

Ask if he was persecuted for suggesting this.

Oh, sorry.

The 1950s, we’re not persecuting, not for that at least.

They were very religious then.

Right, right.

You don’t want to mess with that.

All right, here we go.

Brett LaRue, also Patreon.

If we were to mine a significant amount of a comet, would this change its orbit?

And if so, how could we be sure this would not set into motion future collisions that would result in a major Earth impact?

Oh, let me generalize that question.

As we start poking around with landing on them, mining them, what risk does that pose to taking what was previously a safe orbit and turning it into an Earth crossing orbit that could then kill us?

Yeah, it’s a huge risk.

It is a huge risk, but this is why the people that are looking at doing it are probably looking at focusing on the smaller asteroids or comets if they want to look at comets, but it’s generally asteroids we’re talking about at the moment, because then if they were to dislodge it onto an orbit that was then a hazardous one for our planet, then it hopefully would burn up in the atmosphere and not cause us any issue.

But in terms of mining them, we probably wouldn’t just go to them and mine them.

We’d want to drag them somewhere to what we would consider a safe orbit.

So this might be near the moon, where basically you can just kind of dump the stuff and it just sort of sits there.

It’s this gravitational sweet spot where the thing, basically if it’s a small enough object, it’s not gonna go anywhere.

And then what you could do is have a base on the moon and go back and forth to that object and mine it gradually.

So you basically just want to get it somewhere safe first because sure enough, if you start mining it, you’re probably gonna change its orbit in some way and then it’s hard to predict how it’s gonna spin and where it’s gonna end up in the future.

Good question.

All right, keep it coming.

Fascinating stuff here.

I wish I cared.

When the asteroid’s headed your way, you’ll care.

That’s true, that’s true.

We become the most important people in the world the day that happens.

I’ve seen the Bruce Willis movies.

Yep, yep.

Exactly, it’s all in the movies.

I know, but I’m genuinely jealous because you guys care so much that it makes you learn.

I’m gonna die alone and an idiot because I don’t care about anything.

I’m dead inside.

All right, Doug Bartlett on Facebook.

I know we have found organic material in tardigrades on asteroids.

My question is, are these tardigrades thriving, quote unquote, on these asteroids or in a state of hibernation?

If alive, could it be possible that two asteroids collide or contact and cross breed organisms?

Okay, so I’m not entirely convinced we have found tardigrades on asteroids.

I’m not sure that’s true.

Because that’s like a living organism and we haven’t found anything living.

So these tardigrades are like these crazy organisms that can basically survive anything.

They’re insane.

They can survive extreme pressures and temperatures and they can also just go into hibernation for I think like millions of years and they can just basically survive anything and they come back to life again.

Literally, this is the very edge of my knowledge about these things.

This is very much astrobiology, which is not what I do, but they haven’t been found on asteroids.

But I think the theory they’re talking about is panspermia, where we’re basically looking at transporting biological material around the solar system from one object to another and that’s one of the theories of how life got to Earth.

In fact, it’s not that well accepted in, I don’t know.

I don’t know if it’s fair to say that, but I mean, I don’t believe it personally.

I don’t think that’s how life got to Earth.

But there is a chance that the basic building blocks for life, the more basic carbon molecules came from comets and asteroids and were delivered to Earth in that way, but the actual organisms themselves weren’t, as far as I’m concerned anyway.

Well, but you just said that the tardigrade can survive anything.

So it could survive a trip through space as a stowaway in the nooks and crannies on a rock that got catapulted from one planet to another.

So you said that earlier in this program.

I did.

I did just say that.

And now you’re saying that you’re not buying it.

Oh, he’s calling you out.

Calling you out.

So I think the issue is we need, you know, we’d like some scientific proof.

So we need to do those experiments.

We need to take those bugs into space.

And I’m, you know, I’m sure actually on the outside of the International Space Station, they’ve taken organisms and they’re basically seeing how they react to that radiation environment because it’s not only temperature and pressures.

Obviously, we don’t like radiation.

Our biological cells can’t deal with it.

We get cancer and we die very quickly.

In fact, you know, the astronauts that go into space, there are a much higher risk of radiation poisoning than you would be on the planet.

So this is one of the problems that biological material has in space.

So we need to do those experiments.

We need to take those bugs out into deep space and see if they survive and then see if we can grow things out there as well.

So until we do that, I’m not sure that things can survive in deep space with no sunlight for kind of billions of years that we’d require.

But you know, I may be totally wrong.

That’s a good way to end every statement you make.

I prefer the term special needs grades.

Oh, and tardy grades, oh, I see, I see what you did there.

Well done, both of you.

This is quite a speed date.

So Natalie, we’re running out of time.

Do you have any sort of reflections, simple reflections you’d like the viewer listener to take with them as a lesson for this program?

Yeah, I think someone like me, you’re probably wondering why I’m so interested in these objects, and I think it’s just because I’m inherently interested in where we came from.

We’re not on this planet for very long, most of us 100 years if we’re lucky.

And in that time, I think, well, let’s give a purpose to our life.

I’d love to figure out why we’re here, how we got here, and what we’re leading to our future descendants.

And if basically we may have only got here because of comets and asteroids, and actually in the future, we may die off because of comets and asteroids.

They could collide with us and devastate us and devastate all of humanity.

So I want to understand these objects for many reasons because of how we got here, but also to protect us in the future.

And we need to understand what these things are made of and what their orbits are and understand in so much detail so that we can actually protect the planet.

I think it’s important.

I think everyone should be concerned about it, but not worried.

I don’t think we need to be worried that tomorrow we’re all gonna die in an asteroid impact, although it could happen.

But I think it’s something we need to be concerned with for the future.

So we’re not leaving a ruined planet to, maybe it will be ruined in other ways, but we’re not gonna leave it ruined with an asteroid impact in the future.

And we can hopefully do something about it and divert the asteroid before it hits.

I’d like to think, I’m just picking up on your point, Natalie.

It’s an intriguing and underappreciated fact that asteroids and comets may have been the bringers of life, if not the ingredients of life, but perhaps even life itself.

And yet they can also serve as harbingers of doom for the very life that it brought.

Well said.

Exactly.

Beautiful.

And that is a cosmic perspective.

You’ve been listening to, possibly even watching, this episode of StarTalk, Cosmic Queries, Asteroids and Comets Edition.

I want to thank Natalie Starkey, friend and colleague who went back across the pond.

Good luck in your new science teaching exploits at the Open University in the UK.

And it’s always great to have you.

And how will people find more of you out there?

I am Starkey Stardust on Twitter and Instagram, and you can look at my website, which is my name.

Starkey Stardust.

Great band from the 60s.

And you’re also one of our StarTalk All-Stars.

I am, yeah.

So I have other shows that you can go and listen to.

I’ve had about four now.

So I’ve got some on water in the solar system, a lot of Asteroid stuff.

I looked at the Mars Insight Mission, which is actually on Mars at the moment.

So there’s a few things you can go and check out.

Nice, very good.

And we’ll put a link to those shows in the description.

Excellent, excellent.

And Mark, you get around?

I get around.

I’m on the road every weekend doing my comedy stylings and a comedy club near you.

And go to marknormandcomedy.com.

And I love your tweets.

Oh, thank you, sir.

They’re insightful and clever and funny.

I love yours.

What more can we ask for what the world needs today?

You’re a big inspiration.

You’re a traffic light tweet.

Of course, that’s a joke.

That’s a bit.

Oh my gosh.

Yeah, I’m obsessed with jokes, and that’s a great joke.

Oh, you know, I try joking, but it’s, you know, they don’t always land, but you know where I’m coming from.

I love it.

All right, that’s been StarTalk.

I’ve been your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

And as always, I bid you.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron