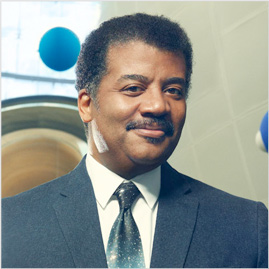

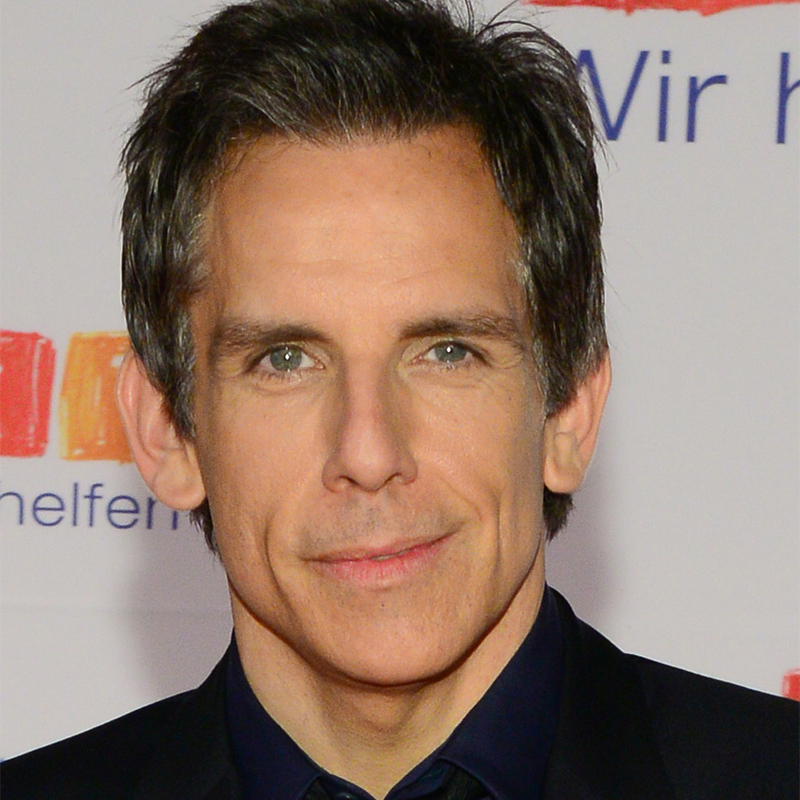

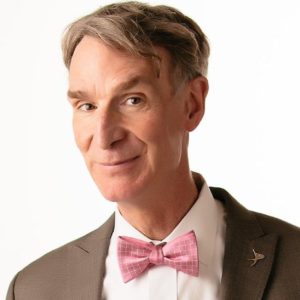

When it comes to the concept of “bringing science to life,” perhaps no movie series in history has taken it quite as literally as the Night at the Museum films. In this episode, Neil deGrasse Tyson interviews Ben Stiller, the star of the franchise, who grew up just 4 blocks from the American Museum of Natural History. Find out how the museum influenced Ben as a kid, as it did Neil and guest astrophysicist Charles Liu, both of whom work there now. Explore the role museums play in making science accessible to the general public, whether the Creation Museum is a legitimate museum or not, and which exhibit Neil would show to aliens if they ever visited the AMNH. Bill Nye chimes in about the power dinosaur bones have to educate and inspire. You’ll also learn what a serious Star Trek geek Ben is, as he describes his personal collection of memorabilia, including the actual Gorn’s head and a set of Spock’s ears given to him by Leonard Nimoy himself. And of course, Neil asks Ben what he asks every guest comedian who appears on StarTalk: whether there’s a science to comedy. Cognitive Neuroscientist Scott Weems calls in to explain how the human brain reacts to comedy, and how the anterior singulate cortex seems to be the center for both understanding humor and resolving conflict. Find out what makes chimps laugh and the importance of rhythm and timing to comedy. Plus, you’ll hear about Zoolander, topology and underwear removal, Neil’s guest appearance in the sequel, and what’s actually on co-host Chuck Nice’s panties.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. And tonight, we're featuring my interview with actor, writer, comedian, Ben Stiller. And we're gonna lay bare his inner geek. You're gonna...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

And tonight, we're featuring my interview with actor, writer, comedian, Ben Stiller.

And we're gonna lay bare his inner geek.

You're gonna learn stuff about him you never knew before, like how much street cred he's got just on Star Trek alone.

Not only that, he starred in the film Night at the Museum, which took place here, at this museum, where everything came to life, literally.

So, let's do this.

Yeah.

Let me introduce my co-host, Chuck Nice.

Hey.

And I have a Charles Liu friend, colleague, Charles Liu.

So Charles, he's a fellow astrophysicist.

He's a professor at the City University of New York in Staten Island.

And so I bring in Charles because he can geek out in ways that I cannot, I'm not worthy.

My delight at being here, Neil, exceeds the boundaries of space and time.

Is that not impossible?

Not for me.

There you go.

So now, we know Ben Stiller, he's a pop culture icon.

Right, given the movies.

He did, there's something about Mary, you remember that one?

Yes, absolutely.

He also did Meet the Parents, there's a trilogy there.

The Zoolander.

And Dodgeball.

Oh, Dodgeball.

Okay, forgot about Dodgeball.

So why do we have him, why do I interview him on the show?

Well he came through town and I just wanted to make sure I nabbed him because I knew that he has a soft geek underbelly.

And on StarTalk, we lay that bare because that's how we roll.

So this museum actually, it turned out played an important role in his life.

Let's find out how and why, check it out.

I grew up about four blocks from here on 84th Street, Riverside Drive.

So this is my neighborhood and being here, actually being here with you in this place At the American Museum of Natural History.

Yeah, the Planetarium, the Natural History Museum, just for me, it's like this feels very close to just my own DNA as a child.

We all came here as a kid.

Yeah, yeah.

And I loved the stars and astronomy and the idea of it.

And I just wasn't a great math student.

And I never really followed through with it.

But I did have a great science teacher, ironically, since I wasn't a good science student, who was my favorite teacher that I ever had at school, where I went to school at Calhoun, which is on 81st Street here.

And that science teacher's name was John Rader was...

We always remember the names of our favorite teachers.

Yeah.

No, you remember because they make a difference.

And he had a genuine love of science.

And that was what I got was that he was really excited by all this stuff.

He encouraged us just to be creative in the sciences.

And for our paper, he said just do it on something that you find interesting in the solar system or whatever.

So, instead of writing a paper about the moon, which is what I chose, my friend Peter Swann and I wrote a song called Man and the Moon that we...

Very creative.

And he gave us an A on it.

And it was about man and the moon and basically that was it.

Man and the moon, moon and the man, where did it all begin?

And how did it all begin?

That's good.

That's good.

Well, I like the rhyme and what he had to do to, literally, to make the rhyme.

And hurray for Mr.

Rader, the teacher, who allowed Ben to learn the material that was appropriate for him and bring it forward.

In the way he wanted and needed to do it.

Good for him.

And that's what education really is.

And it's not only what happens in the classroom.

He came to this museum.

This museum is a teaching experience unto itself.

The American Museum of Natural History.

All the great cities in the world have museums such as this.

A Natural History Museum, you've got the history of life here.

We got the planetarium and the history of the universe as part of it.

And I love this and my paleontology colleagues, because they got all their dinosaur bones up on display.

And I say, one of our asteroids took them out 65 million years ago.

So we win.

We do.

And I was inspired by a first visit to the Hayden Planetarium.

Now, of course, human beings created that show and created the exhibits.

But the moment when I said, the universe is calling me, I was in the Hayden Planetarium looking up to the night sky as presented to me.

And so they just asked quickly, in your visit to this museum or any others, is there some museum memory that you have?

It just blends in with all my other educational experiences.

It's your total knowledge.

How about you?

The Museum of Sex.

Really?

You learn how?

You learn?

You learn how?

Yeah.

Wow!

Well, because Ben Stiller grew up near this museum, this museum ended up part of his life.

And he folded it into his creativity.

And in the film, A Night at the Museum, the creatures come to life.

And so I had to ask him about just where that all came from.

Let's check it out.

First, congratulations on the success of that film.

Now, thanks.

Can I speak candidly about the film?

Sure.

The film was way better than I think it deserved to be.

This interview is over.

No, no, what I mean is, well, no, let me explain.

Let me explain.

It's like, someone tells you the premise.

It's like, no, this is going to be stupid.

No, the animals come to life, the boat, no, but I have to watch it anyway because I'm an employee of this institution.

So, we attended the premiere here at our auditorium and it's like, this is hilarious.

And my gosh, I have fully bought into this premise.

So you made it work.

Well, thank you.

Holy cow.

So this is why you are you and I am me, okay?

When they told me the premise, I thought, that's the coolest thing I've ever heard.

This is my dream, okay?

Astrophysics.

Good.

I'm glad you did it.

Yeah, no, I really was.

I grew up on the Upper West Side.

So for me, I was thinking when I read the movie, if I was 10 years old, this would be really cool, right?

And then I was also thinking, oh wow, I think this is really cool because it's sort of like a fantasy that I always had to be able to, because I came here and you actually thought of real things and trying to solve real problems.

I thought, wow, wouldn't it be cool if, you know, the narwhal in the hall of-

Ocean life?

Ocean life hall, you know, came to life and what would that be like?

So how did you feel about the premise?

I think to be honest that that premise is a horror film for most children.

As a matter of fact, I will venture to say that if I were to poll the audience right now and ask them if the things in the other room came to life, would you think that was cool?

Sitting right here right now?

No, I don't think you would.

I like the premise a great deal.

The basic point, this museum literally did what good teachers do, bring a subject that's otherwise stuffy and still to life.

To life.

A proper use of the word literal.

Thank you.

He better.

He's an astral physicist.

English majors out there, you know what I'm talking about.

And just in the interest of disclosure, some of the exhibits portrayed in the film we just don't have here.

We don't have an Egyptian wing.

We don't have Civil War soldiers, this sort of thing.

But that was okay because the rest of it got the spirit and the soul of what goes on here.

Right.

It really did.

And now when the museum is about to close and the announcement comes on, it's in like nine languages, and people are kind of wandering.

I say, if you stay here, too late.

Throw the bone.

Where do you think the paleontologists get their extra bones?

You know, they're missing a bone?

We need a femur.

I believe your femur will do just fine.

So it turns out the museum attendance spiked after that film.

Really?

People came in, they wanted to see the Easter Island head, which was chewed gum in the film.

If you haven't seen the film, this all sounds completely stupid to you.

That somehow they made it work and it was charming and it was funny.

To this day, we did it beforehand, but it got very popular.

We have sleepovers at the museum.

Oh really?

For people who think that stuff is going to come to life?

For people who are not completely freaked out by the premise of the animals coming.

What they do, they turn off the lights in the dinosaurs and they give you flashlights.

So you get sort of extra shadowing.

Because as you move with the flashlight, then the shadow moves behind it.

Oh yeah, because there's nothing scary about a big giant shadow of a tyrannosaurus rex as a kid.

Sleep tight, Johnny.

Well, what Ben did in Night of the Museum was make it not scary.

And in a sense, all the millions of kids who have now watched it today are not afraid of the dark in the museum and not afraid of things coming to life.

Rather, they're enjoying it, they're looking forward to it.

And I worry that it can be, especially in modern times, we can take science for granted.

Yes.

Somebody's out there figuring this stuff out and presenting it to you.

And I think so many of us think it's just always there.

I once put a calculation in one of my tweets, and someone said, what Wikipage did you get that from?

I said, what app did you use?

I said, I used the Brain app.

You can calculate this.

That's what I did.

And my community of people actually write Wikipages.

And people have to realize that this stuff comes from somewhere.

You know, we do take science for granted.

And so here's what I did.

I took to the streets as our sidewalk science correspondent.

Who gave you that title?

You know, I kind of made it up.

Science sidewalk correspondent.

That's cool.

Yeah.

You know, I just really wanted to go out and see exactly how much the public appreciates science.

Let's check it out.

What scientific advancement can you not live without every day?

I'm not going to say cell phones.

That's the easiest answer.

Okay.

And everyone's become so dependent.

Very good.

So, electricity.

Nice.

Electricity.

Which, by the way, cell phones would not work without it.

What scientific advancement do you think you cannot live without?

Frozen custard.

Well, I'm kind of an agriculture nerd, so I think tractors are pretty important.

Tractors?

Tractors, everything around you is...

Science.

Yeah, exactly.

See?

Even though I was going to go with toilet paper.

Let's talk about science, baby.

What do you think is the greatest scientific advancement in the history of humankind?

I would say space travel.

The wheel.

The wheel.

That is a good one.

A tractor.

Once again with a tractor?

Is there anything more important than science?

Say love, I guess.

Really?

See, but you weren't convinced.

You know science is better than love.

Science is more important.

Oh.

If you say tractor, I swear to God, is there anything more important than science?

Beer.

Beer.

There's the answer, people.

I'm sorry.

We got to cut this off.

Beer.

Coming up next, we'll get back to my interview with Ben Stiller and find out how much of a total geek he really is when StarTalk continues.

Welcome back to StarTalk, right here in New York City.

Featuring my interview with Ben Stiller, and we're trying to find out how much of a geek is he really?

Turns out he's a huge Star Trek fan.

If you're a Star Trek fan, that gets you geek street cred right off the top.

Let's find out how.

The chemistry of the cast was amazing.

The stories were always interesting, and as a kid, you know, sometimes they were funny, sometimes they were more serious.

And I don't know, I just love the show.

I love the show.

So this is a little bit of a geek underbelly going there.

Well, I mean, I don't know if it's that much of an underbelly, it might just be an exposed belly.

Fully raw, just exposed.

Yeah, it's not that hidden.

But I mean, I didn't realize it was sort of geeky to like Star Trek or to be into that stuff.

That's probably the definition of someone who is a geek.

Not knowing.

You actually think it's cool.

But my friends and I, we loved it.

And I actually just found, I got the Star Trek, the Starfleet technical manual when the show was out where you could geek alert.

He didn't even, pause.

He didn't even wonder whether that should just come out of his mouth.

Yeah, yeah, I got, I picked up the Star Trek technical manual, of course.

It's actually very cool because it has blueprints of the Enterprise and, you know, okay, there's no way of.

You're making me feel like a geek?

Come on, man.

No, no, you are at home.

No, I don't mean, no, no, forgive me.

You are at home.

Thank you, I thought I was, you're the life-minded.

This is a safe space, it's a safe space for the geek averse.

I'm sure for real scientists, Star Trek is like a funny sort of little diversion, but for me it's as close as I got to actual science.

But the, yeah, so they did, I mean, it's interesting though.

Isn't it that they would make up a whole book that was fake blueprints of a ship that never existed, and, right?

I agree.

The mythology that gets created around this stuff.

And you were talking, we were talking before about how certain mythology and fiction comes out of first basing it in some sort of fact.

Yeah, yeah, and if it's close enough to being real, then there's enough of an anchor for creative people, technologists, scientists, artists, to say I want that in my future.

Sure.

So, did you glean anything from this technical manual at the time?

Well, I literally just found it recently, like in a box of old stuff, and of course I just, I got very emotional, you know, because it's my childhood, and I was like, oh, my startlingly technical manual.

But I mean, what I found interesting was that there was so much detail put into something that was totally fictional, but I think we all want to kind of believe these mythologies, and that's what you invest in, whether it's any science fiction, I think, you know?

And I think Star Trek did sort of, because he was telling stories that were based in what was going on at the time.

Culturally relevant.

Yeah, definitely.

It felt that connection was there.

So Charles, you're our Star Trek geek-in-chief, and so did you have a Starfleet manual?

I got it out of the library.

Nice, like that's geek-squared right there.

How about you, Chuck?

Yes, I have one too.

Okay, so now you're on level ground with Ben Stiller.

I liked Ben before, now I really like him.

He was talking about the social relevance of Star Trek, and it's so true.

At that time especially, never mind things like racial issues, social, people getting along and anti-war.

At that time, right during the Cold War in Vietnam, there are a series of episodes that address directly a hope for a better humanity.

There's a huge cultural tapestry from which to draw story lines if you're gonna make commentary.

Absolutely.

And let us remind ourselves of course that Star Trek just enjoyed its 50th anniversary.

Yes, absolutely.

So, hearing that he owns a starship manual, we only just scratched the surface of Ben Stiller's geek-itude.

I'm telling you, the dude is borderline obsessed.

Tropic Thunder, which is the one that I directed, there's in Matthew McConaughey's office, he plays an agent, I got my Spock ears in there as part of his, like in his office on his desk.

Oh, what do you mean you're a Spock ears?

The Spock ears that I purchased at auction, Neil.

That I proudly purchased at auction a number of years ago.

So you own an original set of Spock ears?

I do, from, yeah, I think from the second season.

And I actually-

And then you put those on set.

You realize it's Hollywood, they could just make a prop.

You realize that?

No, no, well, I'll keep going with this.

I also put my Gorn head that I own.

You have a Gorn head?

The Gorn head from the Arena episode in that same, I can tell you a couple stories about this, okay?

The Gorn, this is the lizard creature that Captain Kirk fights.

That's right, I have the Gorn head, which I also bought at auction, and the Gorn outfit, his uniform.

So the Gorn head was actually in, I put that in the office too.

Wait, wait, just pause for a minute.

Just the very phrase, I own a Gorn head.

That, that, I own a Gorn head.

Those five words either mean absolutely nothing, or mean everything.

Or mean, exactly.

Right.

That defines who you are as a person.

It's like some sort of a Rorschach test for personality.

Amazing.

For what your values are in life.

But I've never put the Gorn head on, just to let you know.

I'm not that weird, okay?

You draw your line.

But the cool thing for me was that Leonard Nimoy did spot the Spock ears when he saw the movie.

Which was, and reached out to me, which was probably one of the best moments of my life.

Did you get him to sign it, or was it?

He, you know what, I told him, he said, did I spot some ears in that scene?

I was like, yes sir you did.

Your ears that I purchased.

You didn't start the conversation, I'm not worthy.

Basically, I was just, you know, I was a mess.

Bumbling.

Yeah, I was very excited, because he really is one of my favorite people, and the fact that I got a chance to meet him, and that he noticed the ears, and I said yes, I'm a huge fan, and I told him that I also had his tunic from the pilot episode, and he said, oh well, okay, give me your dress, I want to send you something.

And he sent me a set of his ears from the first, from the Star Trek movie.

From the movie?

And that basically is like my life could end.

There it is.

So that's why I'm retiring.

You're done, bucket list complete.

Wow.

I just love how, no matter how much or who you are, you have to be very sheepish when you say, like, I have Spock ears.

Like, he was like, and I have Spock ears.

No, no, but I told him he's in a safe space.

The only thing I would ask is, Mr.

Stiller, may I please put on the Gorn head?

I mean, I'm going to be honest, when he said that, I didn't understand that.

Why do you buy a Gorn head and not wear it?

I'm not only wearing it, I'm saying to my wife, look, you won't have to close your eyes because I'm wearing this Gorn head.

Oh, no, no, no, no.

I tell my wife, honey, take a look, I'm wearing a Gorn head.

So, you know, ears are, they're an interesting marker.

And I think if you otherwise have a humanoid looking creature, do you give them three eyes?

Generally not.

Do you give them a, do you put the nose on their cheek?

No, you just sort of give them new kind of ears, it seems.

It seems to be the way that you can make use of your very gorgeous actor without screwing up their face.

Oh, is that, okay, that makes sense.

I have a friend, Sarah, who that's her philosophy on why all aliens have weird ears as opposed to...

Well, plus in the mammal, among mammals, ears vary greatly.

They have floppy ears, pointy ears, and ears that stick out and ears that can aim.

And let's face it, in the 1960s, costume-making technology only went so far.

Evidence by the Gorn Head.

That's the sound they made.

Yes, but I really...

That was very good.

Did you like that?

Which by the way, he's spoken to a translator and he would go...

And be like, Kirk, let me tell you something.

It was great.

A translator provided by the Metrons was trying to prevent an interstellar war.

Because it was actually like an interstellar cable show.

All right.

The room...

I can't believe we just did that.

So coming up, we continue my interview with Ben Stiller and we break down the very hard science of how to remove your underwear next on StarTalk.

We're back on StarTalk, featuring my interview with Ben Stiller, actor, comedian, writer, and I had to call him out.

In one of his films, there was a bit of scientific inaccuracy in a really important scene, and I had to raise that issue with him.

Let's check it out.

In Zoolander, there's a scene where Hansel's walking down the runway, and then he pauses, sticks his hand in his pants.

Nobody knows why, and he's reaching around.

Why is he doing this?

And your character says, why is he sticking his hand in his pants?

And then a few seconds later, he comes out and there's his underwear.

And I must alert you that that is topologically impossible, what he did, but I give him credit for even going there.

Right, but there is a topological way to approach it, right?

There is.

In fact, you can remove your underwear without taking off your pants.

But he has to like, you need very stretchy underwear to pull one side around your foot and then back up, and then it slides across and comes out the other side.

But maybe he did that really quickly and we didn't see it.

Oh, at a point where the camera pulled away.

Or just have it so fast.

So I just briefly mentioned topology there.

That's a branch of mathematics that thinks deeply about surfaces and how the surfaces connect or interconnect and how you make shapes.

It's a fun branch of math.

And if I were a mathematician, I think I'd be a topologist.

Yes.

Well, you know what?

Here's the funny thing, Neil.

When I found out about the topological reference that you made, I felt that I had to be able to demonstrate that it is possible.

What?

Yes.

Do it!

I forgot I was wearing these this laundry day.

What is on the front of that underwear?

Here, man.

What am I doing on the front of your...

First of all, they're red, and I think the word for these is panties.

And I'm just realizing, here, this isn't Saturn.

What is it?

Based on the coloration and how thin the ring is, this is, in fact, Uranus.

I'll just be glad it's not Uranus.

Are there any Klingons orbiting?

Give me my underwear!

So, let me ask you guys, because I think about this all the time.

Where would you place the threshold of science accuracy after which they cross that line, they go into storytelling?

Storytelling abandoning the science accuracy.

Do you have a line?

I have a line, and that is completely, you know this based on scientific research, that's fact.

If you don't know it, it becomes fiction.

It's a very clear line.

Scientific knowledge has been tested.

No, no, wait, wait, is that answering my question?

I'm asking you, there's a science fiction story.

How much science should they put in correctly?

And how much, so where's the line?

In that, if you're going to call something science fiction, you don't need any science at all.

It doesn't have to be, because what we're talking about at that point is just creating a world that is sufficiently different.

All we need to do to create science fiction is to create some sort of world environment which is sufficiently different from our own that we can start commenting on our own in a distant, detached way.

But I will say is what makes good science fiction is the more science you have in your science fiction, the better your science fiction is.

I'm thinking you anchor it in what is real, then step to where your fantasy takes you.

A lot of people think this, but let me give a counterexample.

You give your counterexample after I give you a quote from Mark Twain.

Mark Twain was a science fiction fan?

First get your facts straight, then distort them at your leisure.

Nice.

Mark Twain.

Star Wars, for example, is patently unscientific in literally every way.

The fact that it has planets and spaceships is about the only accurate science in Star Wars.

If just one of those X-wings would actually go to warp speed while it was sitting in orbit around a planet, it would wipe out the atmosphere of that planet.

And yet they do this all the time.

That's just one tiny example.

Why do X-wings make the same sound when they're whizzing around in space as they are when they're flying in an atmosphere?

I pose that very same question.

These things don't matter in the quality of Star Wars as a science fiction mythos.

It is a beautiful, brilliant thing.

So you're telling me I overreact when I comment on this?

No, no, no, no.

When somebody says that they're doing science fiction, then you can suspend all disbelief and it's okay if they get it wrong.

So here, let me meet you halfway.

If you're going to make science fiction and you want to create a world, let that world be internally consistent in whatever rules you create for it no matter how different they are from our own.

So don't violate your own rules.

Don't violate your own rules.

I am happy with that.

All right.

Well, I am so glad that we settled this.

We settled it.

So, moving on to other works of Ben Stiller, I made a cameo appearance in Zoolander 2.

No.

Really?

Yes, I did.

It was filmed on location in Rome.

And I flew to Rome for this.

Except, while it was on location in Rome, it was in a studio in Rome.

So they could have done it here, but everybody was in Rome, so I had to go to Rome.

And we wonder why movie budgets are so big.

And one of my scenes was on location with Owen Wilson and Katy Perry.

And the very last shot of the film is me doing Derek Zoolander's famous Blue Steel.

I'm in this movie.

My earlier scene has very loose cosmology in it.

This is a throwaway at the end.

And a wonderful throwaway it is.

But I would ask, should I keep doing this if I'm asked?

Yes, absolutely.

Because is it really, why?

Are you kidding me?

I would do that for no reason at all.

No, I need reason.

I don't need a reason to do that.

Look at that.

Yes.

Are you kidding me?

So if you look at this frame by frame, in one of the frames there are like moons and planets coming out from the thing.

So there is a cosmological reference to it.

You don't need one.

No need for a cosmological reference with that.

That, my friend, is called fabulousness.

You absolutely should keep doing this.

And the reason is, to me, very simple.

Every human being has a combination of the serious and the excited and the crazy.

And if this is you, you just do it.

That is simple as that.

Alright, I'll take it to heart.

Thank you for that.

Well, up next, Ben Stiller helps us break down what might be the science of comedy on StarTalk.

We're featuring my interview with Ben Stiller.

And I don't know if, unless you've been living on another planet in another dimension, he has surely made you laugh at some point in his career, in your life.

And so I had to ask him, is there a science to comedy?

Is there some kind of a formula?

Let's check it out.

You know what, I think it's an instinctual thing that does have some sort of math to it in some way.

Okay, what equation?

I'll write it down.

But no, there is the old rule of three with a joke where you have this set up.

Where if there's something funny, it's the third thing that's funny.

Like you say, the two regular things and then the third thing is the funny thing.

Okay, it's not the eighth thing.

No, right, yeah.

And that is like a rhythm thing.

It's like a timing thing that is, I think, is an instinctual thing, probably the way instinctually you gravitate to...

Good word, gravitate.

Yeah, gravitate towards mathematics or how those equations work, how you have sense of it.

There's a way to think about it, a way to set it up.

And I think that that spurred your interest in it because you had a knack for it and an understanding of it just instinctually.

And I think that's the way it is with comedy, that you could probably break down and go, yeah, that actually does have some sort of an equation to it.

So Chuck, is comedy instinctual to you or is it formulaic at some level?

You know, yes, both.

Really, no, seriously.

The truth is, it's both.

I write material and then I go on stage with the full intent, if that's not working, to abandon that material because I trust that I'm funny enough to make it work.

So some of it is timing, some of it is instinctual.

And there are different ways to actually create jokes.

Like familiar associations coupled with surprise is something that's very familiar to everyone, you know.

If you bring about familiar associations and then you interject something that's surprising, people will most likely laugh, you know.

Or at least react.

Or at least react, you know, right.

And believe it or not, that's the biggest conundrum of being a comedian is that you write in a vacuum, but you find out if you're funny in public.

So you don't know if you're funny until you actually do.

Until you're not funny.

Until you're not funny.

And that is it.

So comedians suffer from delusions because you think you're funny when you are not.

You can think you're funny when you're not.

No, you just think you're funny when you're not.

Well, so here at StarTalk, we keep a rolodex of like experts on stuff.

And we got somebody who thinks about just these sorts of questions academically.

Oh, we got just a guy, okay?

His name is Scott Weems.

He's a cognitive neuroscientist who studies the science, the science of what makes us laugh.

And I think we got him standing by right now on video call.

Scott, hello.

Welcome to StarTalk.

So you've been eavesdropping on this conversation.

Do you agree with Ben Stiller that there's some, at least some kinds of comedy are formulaic?

Well, I think there's definitely a science to comedy.

I'm not sure there's a formula in the sense that you can define this will be funny and this won't.

It takes practice like any other art.

So as a cognitive neuroscientist, presumably you know which parts of the brain get stimulated by what kind of jokes.

I do.

I mean, people have been put in scanners like MRI or tools like that and then studied while they're like looking at cartoons or listening to jokes and things like that.

And there are certain parts of the brain that are generally active.

The anterior cingulate seems to be like the kind of the center for resolving conflict and getting jokes, which tells us there's something in common for those two things.

Yes, because when you are funny, that's a very good way to diffuse conflict.

You know, it kept me from getting beat up quite a bit.

And so is laughing and humor strictly human or are there other animals out there who can do this?

No, we're definitely not special in terms of humor in the sense that lots of animals laugh.

We know that apes laugh.

That's a relatively straightforward one.

And the more similar their vocal cords are to ours, the more the laughter actually sounds like them.

But wait, but what are they laughing at?

It depends on what you think is funny if you're an ape.

I mean, apes...

They're not laughing because they have a stand-up comedian in front of them.

What makes an ape laugh?

Well, let's just say we're talking about animals that throw their own poop.

You're actually right on with that.

Yeah, so there's actually a very famous story of Washoe, a chimpanzee who was taught sign language.

And there was one day she was sitting on her handler's shoulders, and all of a sudden, out of nowhere, she just peed.

Just peed on her shoulders.

And he looked up, obviously, covered in urine.

This was not a pleasant thing.

And she was making the sign language sign for laugh, for funny.

So I think if you aren't ape, most of your humor does have to do with pee and feces, because there aren't stand-up comedians.

Who knew there was an R.

Kelly in the chimpanzee world?

Scott, we got to end this now.

But thanks for checking in with us.

And the day you actually write out a formula, I want to be the first one you call.

No, please make him the second one you call, because I do this for a living.

Alright, Scott, thanks again.

Coming up after the break, award-winning actor, director, Ben Stiller, karate chops me in the neck.

Next on StarTalk.

We are on StarTalk, right here at the American Museum of Natural History, featuring my interview with Ben Stiller.

He's a comedian, and you think he's fun because you see him in the movies and on TV?

He's just that fun in real life.

Check it out.

Is there an impression that you can do of someone that could just be fun?

Was there?

God, I am so bad.

I'm not good with the impression.

You must have been able to do Captain Kirk.

Don't tell me.

No, I do a bad Captain Kirk.

Can we just try it?

No, I can do Captain Kirk in a fight.

Okay, I can do Captain Kirk in a fight, okay?

So you have to bear hug me, right?

Okay.

Like you're trying to squeeze me under a Klingon or something.

Should I pretend or do it for real?

Yeah, no, do it for real.

And then I'll do how Captain Kirk can get out of it.

Okay, okay, ready?

Okay, right.

Ah.

That was how he would get out of something.

You're right, that's what he did every time.

Just a double karate chop to the shoulders.

So there were other powers that were expressed in Star Trek.

So there was the Vulcan mind meld.

Yes.

And Charles, just tell us what that was real quick.

Vulcans are very telepathic species.

They could literally project thoughts into other people as long as they touch them in the nose, in the forehead and on the cheek all at the same time.

Yes.

Because those are the erotic zones of Vulcans.

And there's also the Vulcan nerve pinch.

Yes.

Which I attempted throughout.

That was it.

Chuck has the power.

Chuck has the force.

That was either the Vulcan neck pinch or I'm a televangelist.

So Charles, I spent a lot of my childhood trying to paralyze people with a Vulcan neck pinch and it never worked.

I got a really strong grip at one point.

I can squeeze like 240 pounds with my hand.

All you have to do is take a scale and squeeze, okay?

And you can see what it is.

So there it was.

So I did this on people's and I tried here and here and here.

Nobody ever dropped.

Well, that's just because Vulcans are even stronger than humans.

They're like three or four times stronger.

So if you could have nerve pinched, say 800 pounds, it would have worked every time.

Because you would have crushed his clavicle.

Yeah, you would have broke his clavicle with no problem.

Right.

Yeah.

That's why I do something called the Vulcan Nut Punch.

And it works every time.

Vulcan Nut Punch.

I've just been notified right now on the show.

It's time for Cosmic Queries, a fan favorite.

All right.

This is where we solicit questions from our fan base and the topic at hand today.

For these questions, is all about bringing science to life.

Seeing them?

Yes, yes.

Just as this museum did in Ben Stiller's Night at the Museum.

So what do you have?

Awesome.

So let's go with at Keith Garris from Twitter says, if you could pick one exhibit from any museum to come to life and interact with for a night, what would it be, Neil?

That's easy.

Yeah?

In the planetarium, if we show a black hole, I want to bring that out of the sky and put it right here in the exhibit.

Right on.

Let me just say.

Just keep your distance.

This is from Joshua A.

Mikhail from Phoenix, Arizona.

It says, if aliens were to visit Earth and go to the American Museum of Natural History, which department or exhibit do you think they might find most interesting?

The Hall of Biodiversity.

No question about it.

There is laid bare the entire range and scope and spectrum of how matter has found a way to become alive here in this museum.

And it is laid all in full view.

So we would say, here's what we got on our planet.

Got you.

Now what do you have on yours?

What do you have on yours?

Right?

Yo, that's a...

There you go.

So now, Saptarshi Mandal from Davis, California says, Dear Dr.

Tyson.

Oh, how formal.

Has there ever been a scientifically inaccurate museum exhibit which was later corrected as more accurate science came to be discovered?

That happens all the time.

Really?

All the time.

What's more typical is not that something is inaccurate, that can happen, but what's more typical is the museum exhibit has kind of lost why it matters because something matters more than that later on.

Right.

Because something, we know it better than what was known back then so we can add precision.

So you got to redo the exhibit.

So any museum worth anything has got to be a living display of the science that they communicate because science is a never ending frontier.

Cool.

Austin Belluccio from San Jose, California wants to know this.

What is your opinion on places such as the Creation Museum who showcases the Bible as literal knowledge?

Should it be considered a museum?

In this country of ours, which is we at least tell ourselves, has freedom of speech and we celebrate the plurality of who and what we are, that would include belief systems.

I personally have no problems with any kind of museum you want to put up.

The problem arises when you take something that is a belief system and then want to impose that belief system on the plurality of your society.

That is very different from taking something that is objectively true and sharing that with the country.

Science and its methods and tools establish what is objectively true.

And that means it's true whether or not you believe in it.

But if you have a creation science museum, it's not actually science, it's a belief system put into a museum form, fine.

But now if you're going to legislate that way and you want others to think that that is the truth rather than your belief system, that is the beginning of the end of an informed democracy.

So you're welcome to your belief system.

You yourself are welcome.

It's a personal truth.

It's a personal truth.

It's not a universal truth.

Exactly.

Exactly.

That was a damn good answer.

That was a damn good answer, my friend.

Up next, my good friend Bill Nye, the Science Guy, has thoughts about bringing science to life, when StarTalk returns?

We're back on StarTalk, featuring my interview with comedian, actor, director, Ben Stiller.

And he had some parting thoughts on the role of humor in the universe.

Let's check it out.

In reality, I think there's humor within serious situations.

Just life has humor within it.

And that really makes something feel more real.

That's what I feel about the universe.

I think it's dripping with humor.

Yes.

The universe is a hilarious place.

Like describing how you die when you fall into a black hole, that's hilarious.

I'm just, I'm just saying.

Yeah, sure.

The fact that as big toothed as T-Rex was, it doesn't do a damn thing when the asteroid comes.

He could be the top of the food chain and you're still wiped out by an asteroid.

I mean, those are bigger questions in the universe, I think, in terms of that people get involved in their own problems and just get focused on all these issues in their life because they're afraid of dealing with the bigger issue of like, why are we all here?

What is this all about?

And you know, those are the questions of the universe.

What, what, what?

Would you agree that the universe is dripping with humor?

I think.

Oh, of course, yeah.

Like, you know, the dead T-Rex, man.

It's filled with humor, you're right.

We thought this was all this way and then it's like, you're totally wrong.

Ah, ah, ah.

But wait, wait, but do you think it's a coping mechanism?

Yes, 100%.

To deal with certain existential uncertainties?

Absolutely.

Absolutely, if we did not laugh at ourselves, we would cry.

Because there's so much that we still don't know.

Well, before we wrap this up, I got to catch up with my guy Bill Nye, okay?

This dispatch comes from right here at the American Museum of Natural History, the setting of Ben Stiller's film Night at the Museum.

So let's check out my boy Bill.

So how do we bring science to life?

Well, this is a Tyrannosaurus like Rexy from Night at the Museum.

That's one way.

Museums are full of artifacts that tell us about the history of humankind and the history of the earth.

Now, the Tyrannosaurus lived about 65 million years ago.

And as iconic as the Tyrannosaurus is, we've only found 15 reasonably complete skeletons.

But let me tell you something, my friends.

15 is infinitely more than zero.

We know that these animals once roamed the earth because we found their bones.

And paleontologists have thought long and hard about how to arrange the bones so that they appear the way they would have in nature when the animal was alive.

And I'll tell you, when I'm here and I look at the skeleton, it's easy for me to imagine a walking, talking, stalking dinosaur.

It's as though these bones bring these animals to life.

So do you have any parting thoughts about bringing science to life?

Well, don't do it by trying to show people the underwear that you are currently wearing.

So Charles, any parting thoughts?

As a professor, as an educator, it is my goal to bring science to life every day to everyone who is willing to learn.

Something like Night at the Museum, which Ben and his colleagues did so well, really helps us in making that happen.

When I think about bringing science to life, I mean, I'm a scientist, and it's not really a scientist's job to bring science to life.

It's our job to discover how the world works using the methods and tools of science.

And so that forces me to reflect on what it actually takes to bring science to life, and I'll tell you what it takes.

It takes a system in our culture, in our society, that makes it clear that science is everywhere.

It's a part of our lives in practically every way that matters.

And there's no requirement that everyone becomes a scientist.

I don't want that world.

That would be a boring world.

No.

When I try to encourage science interest, my actual goal is to enable everybody in our culture to embrace science for what it is.

And if some among them are artists, then they can take the science that they learn and fold it into their creativity and create a masterpiece of artwork, a sculpture, a movie, a novel.

And then, then, science has become the artist's muse.

Only then can we claim that science is part of culture, the way it always should be.

That's a parting thought from the cosmic perspective.

You've been watching StarTalk.

I've been your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Chuck, thanks for coming.

I've been your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

As always, I bid you to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron