Part 2 of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s interview with celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain is all about cooking and eating, from the experimental techniques of molecular cooking to the “Nose to Tail” movement that incorporates respect for the animal into the culinary process. Anthony explains how to avoid getting food-sick in exotic locales and why he’ll never again drink cobra blood out of a snake’s still-beating heart. NYU Professor of Nutrition Marion Nestle tells us how to avoid food-borne illnesses here at home, while co-host Eugene Mirman shares his advice for curing viruses and the common cold. You’ll learn why we can’t eat wood, why eggs get fluffy when we cook them, what altitude does to the human palate and what type of food the astronauts on the International Space Station desire most.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Now. Welcome to StarTalk Radio. I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson. I'm an astrophysicist with the American Museum of Natural History, right...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Now.

Welcome to StarTalk Radio.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

I'm an astrophysicist with the American Museum of Natural History, right here in New York City, where I also serve as director of the Hayden Planetarium.

And I've got with me, you've seen him before, you've heard him before, Eugene Merman.

Eugene, thanks, you've invited us to your Eugene Merman Comedy Festival, which is a great thing you got going over there in Brooklyn.

Thanks for having us be a part of that.

Thanks for being with us.

And just recently, we did a show with you, and our name was on the poster.

That was great, yeah, I've been on a poster before.

Well, welcome to posters.

Very cool.

I'm gonna make you a star, Neil.

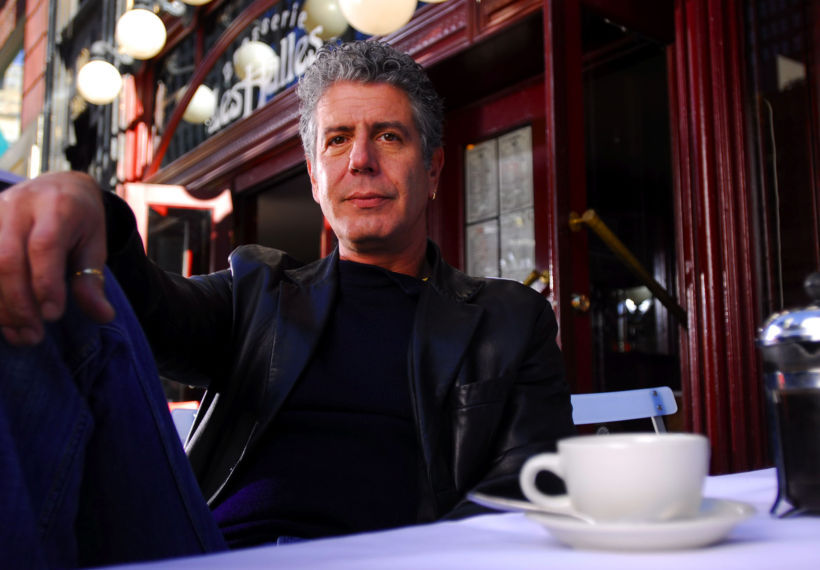

So this show is about nutrition, and we're featuring my interview with Anthony Bourdain.

You might have seen him with his television show on the Travel Channel.

He's gonna have a TV show that's, in fact, he's gonna move to CNN and do a food show.

It'll be like Anderson Cooper in the middle of a food disaster, picking up food going, why?

And I said I couldn't do this just with Eugene, although Eugene is a bit of a food expert, because you're a voice on Bob's Burgers.

Yes.

You know, so he's got some food expertise.

And I got a D in chemistry, so I bring that also to the table.

But I had to bring in a little more expertise.

No offense here.

Not offended.

Down the street, we've got New York University, a great institution, one of the jewels in the crown of New York, and we have Professor Marion Nestle, Professor of Nutrition.

Thanks for joining us on StarTalk Radio.

Thank you.

So, Anthony Bourdain, you certainly know the guy, and you've heard of him.

Yeah, yeah.

And so, we've got a clip of my interview with him, filmed previously, but we talked about just being in the kitchen as a place to experiment, what kind of gadgets are available.

When we come back, I want to talk about sort of food science and the science of the kitchen and what that means to you.

Let's check out my first interview clip with Anthony Bourdain.

What do you think of all the gadgets that help people cook food?

They're great infomercials.

In almost every case, they're completely worthless.

The salad shooter, do you really, you know, the ultimate salad delivery system, I mean, is cutting lettuce so hard, you know, something that will cut onions for you is completely insane as far as I'm concerned.

There is no better, two good knives, a serrated knife for bread and maybe tomatoes and a good quality chef's knife is all you need and a cutting board, a couple of good heavyweight pans and there's very little that you can't do.

How do you distinguish between tricks?

And I don't mean it in a circus sense, but just secrets versus 10 years of doing it.

Chris, you serve a food to someone and say, what's your secret?

As though you can just tell that to them and then tomorrow they can do exactly what you made.

There are no-

At what point do you say, look, I've been at this my whole life.

There are no secrets.

The secret of the restaurant business and professional cooking is there are no secrets.

It is a mentoring business.

Chefs spend their whole lives learning stuff and then because of the nature of the business, every few months teach everything they know, invest time they don't have in teaching somebody everything they know so that they can maybe have a Sunday off and that they can count on a crew.

It's a military hierarchy.

There are no secrets.

There are no secret recipes.

There are no secret techniques.

Everything that you learn in the kitchen you were either told open source by your immediate superior, and that's been shared with everybody in the kitchen, or you have learned it over time painfully.

You know, the ability to tell when a steak is cooked by listening to it in the pan or on the grill or determining that a piece of fish is probably ready to come out of the pan just from the sound of it.

These are things you learn through repetition, and that is the great secret.

It's that this is how professionals learn.

This is how home cooks should learn.

People shouldn't be intimidated by recipes.

They should understand that professionals learn through getting it wrong, getting it wrong, getting it wrong, getting it wrong, starting to get it right, eventually getting it right until it became second nature.

It's repetition, repetition, repetition.

You learn all of these things, even if you don't understand the science behind why your stew is transforming, why it's becoming thick as it cooks longer, why your egg scrambles, why the steak gets dark on the outside when you expose it to heat.

You may have no understanding of the science behind that, but you instinctively, of course, through repetition, understand it, you learn to use it, and you count on it.

Now, you've used two words in our conversation as fluently as any scientist that I know.

First, E coli just rolled off your tongue.

And tectonic shift rolled off your tongue.

So, what is your science background?

What did you?

High school science.

High school science, but...

But you liked it, I guess.

I did, but people talk about things in the kitchens, like what's happening?

Why is my steak getting brown?

The caramelization of protein, the Maillard reaction.

That's kind of cool to know.

It helps you out to understand.

I'm betting you didn't learn caramelization of sugars in high school chemistry.

No, you learned it real quick.

First time you stick your finger in some, you learned it on a cellular level.

How come that's hotter than water?

I hadn't counted on that.

It's way hot.

So that interview, I just became so enchanted by him.

I felt like I've known him my whole life by then during that interview.

So we're back in the kitchen.

You like the kitchen.

Why, it's the one place you can do legitimate science experiments and no one will fault you for it.

Absolutely.

And if you're really a good cook, you keep notes on what you're doing.

A lab book.

If Iran tried to build a nuclear weapon in a kitchen, no one would be so upset.

So if your cake fails, you try it another way.

I'd be curious if on her shelf of cookbooks, she's got lab books of what failed cooking experiments, successful ones.

So is there some experiment you remember most that you discovered yourself?

Well, it's just anything that you make.

You just keep making it until it works.

I think it's interesting that if you cook protein, it sort of changes.

Yeah, what was he saying when you would burn your finger if you touched sort of...

Did you need him to tell you that you'd burn your finger if you touched it?

No, but he said faster than water.

Oh, yeah, yeah.

Oh, sorry, I don't know science, astrophysicists.

Yeah, if you melt sugar and it's liquefied, it's at a higher temperature than boiling water.

And it sticks to your finger, so it'll, yeah.

And if you look at chefs, you look at their arms and they've got blisters and cuts all over them.

Yeah, because they've been fighting food for years in a hot kitchen.

So yeah, so like for example, egg goes from liquid to this fluffy form because you're heating the proteins.

I mean, it's an interesting sort of consequence of it.

And cream whips.

Cream whips.

Because you're beating air into it.

Right, right, right, I mean, I love it, I love it.

When we come back, more of my clips with Anthony Bourdain and I've got Eugene Mermin and the good professor of nutrition, Marion Nesk.

StarTalk Radio, we're back.

Find us on the web at startalkradio.net.

You can listen to us three ways.

You can download the podcast on iTunes and our website.

You can find us in the airwaves, StarTalk Radio Radio.

Also, we are on the Nerdist channel under YouTube.

Check us out, you'll see us in video form.

I've got Eugene Mermin.

Eugene, thanks.

Sure.

Thanks, and the good professor.

Thanks for agreeing to help out on this interview.

I interviewed Anthony Bourdain, and I didn't know very little about him, and I got so...

Yeah, did you ever watch his show?

I did, you know, we used Channel Surf, and all the food folks.

He's wonderful.

Yeah, it's great to learn about, and he's got a new show on CNN where he travels the world, and he gets paid for that.

Yes, I think most of the people on CNN are given money and exchange for their skills, is just to travel around eating things.

Eating things, and he's just actually pretty slender, so he's watching what he eats.

So, in my next clip with him, we talk about the molecular food movement, something I was unsure what that meant, but it's all the rage, and let's find out where that takes us.

I'm reading recently about the molecular food movement, where if you have enough power over molecules, just create the food from a molecular kitchen.

What do you think of that term?

I think it's an unfortunate term.

It's treating ingredients in new ways.

It's manipulating preexisting ingredients into unusual forms.

And I guess the father of this movement was a guy named Ferran Adria, a great chef, a great restaurant, one of the most enjoyable meals I've ever had in my life.

Where?

Called El Bulli in Spain.

50 cooks cooking for 50 diners.

Never made a profit, considered by many to be the best restaurant in the world.

What Ferran explained, what he did like this.

He said, he's asking a basic question.

Here's a truffle in this hand.

Here's a perfectly ripe peach.

The truffle's $1,500.

The peach is a dollar.

Which is better?

Which is better?

This is rarer, it costs more money, but is it more delicious than a perfectly ripe peach in season or a pear?

So he started to ask, what if I treat the pear like the truffle?

I do everything I can that experimentation and science says.

If I trick you into thinking you're eating a truffle, if I serve it in a way that you were forced to value it, that draws the eye, that changed the texture, what can I do to this, to change its value, its perceived value, to surprise you, to take you someplace you haven't been before, but then bring you ultimately back to something that at the end of the day, tastes like a delicious, delicious pear.

So yeah, they use a lot of natural, mostly natural ingredients like agar-agar, the stabilizers, various processes to either intensify flavor, to trick the mind into, you know, eating a strawberry that doesn't look like a strawberry or an apple that looks like and feels like caviar in the mouth.

That could be fun and exciting in the hands of somebody as talented as Ferran and it could be a long, miserable night in the hands of somebody who read about them and thought it was a cool idea and started doing ghastly and terrible things to food, sheerly to dazzle.

Why is that different from, I go to the cheap deli and they've got the crab salad, but it's fish made to look like crab?

Ferran would agree with you absolutely.

There is nothing different.

It's a technique and a process just like making ham.

A leg of pork is a good thing, but as it turns out, if you pack it in salt and then hang it and age it and smoke it, it becomes even more delicious.

So it's basically taking that same engine, whether we're talking a sea leg, as it's called, that fake crab, or the making of ham to an extreme degree.

Okay, but at least that's still using natural ingredients or ingredients available to them.

It's not really coming out of the chemistry lab.

This is not chemistry lab.

So molecular movement is not the bad name.

It is modernist cooking that understands and refined and they spend a lot of time in workshops or laboratories figuring out why does an egg scramble?

What process is happening already when you agitate and beat proteins?

Right, so how can we play with that process?

We're not talking about introducing chemicals.

In almost every case, most of the stabilizers or things like these were extracts of or natural ingredients that are used elsewhere in other cultures.

So it's not chemistry class, but it certainly does look like a laboratory.

One of his more famous dishes is the spherified olive, which is essentially the extract of the best olives turned into juice and then dropped into a solution treated with a substance, a natural substance, which causes it to basically spherify into a liquid sphere contained only by itself.

So you pick up something very delicately that looks like an olive and it explodes into liquid.

It's thrilling and delicious.

So it's like the essence of olive turned into a bigger olive.

Just as delicious as the original olive, but with excitement, surprise, wonder, and 50 courses of this, it's really like taking off to the moon.

You look stunned by this description of the essence of olive turned into an olive.

I've had one, actually.

You've had one, and what is it?

It's like having a mouthful of olive oil.

Good olive oil, mind you, but still olive oil.

Like best ever olive oil.

But little, but not as thick or as thick?

Yeah, pretty much.

It just tasted like olive oil.

If you take the essence of an olive, that's oil, right?

That's what olive presses do.

Well, I'll go home and drink some olive oil and be like that.

And you'll save yourself a great deal of money.

So are these chefs gone awry?

Is this like...

Oh, I think they're having fun.

It's boys with chemistry sets.

They're not murdering people.

It's chemistry sets.

They get to play with all this really cool equipment.

They get to play with liquid nitrogen.

What could be more fun than...

I want a liquid nitrogen nozzle in my kitchen.

See, there you go.

I've always wanted that.

I think you probably could have one, right?

I could probably rig that, actually, now that you mention it.

So if you had that...

Liquid nitrogen is very cool.

It's nitrogen like in the air, in case you didn't know, 78% of the air you breathe is nitrogen.

If you cool it enough, it will liquefy, but now it's like raging boiling because it boils.

It's boiling at a very cold temperature.

What would happen if you sprayed it on a fish?

You would instantly freeze the fish.

And then you microwave it, would it be delicious?

Freeze it, then microwave it.

Then you have a mushy fish.

Just trying to see how well you know science.

I've never tried that, but I think that's what would happen if you did this.

Maybe there are things that a chef could still do to food that these boys with toys haven't yet devised.

Well, they're working on it.

There are lots of them working on it.

Wouldn't it help if they knew the chemical properties of fat versus protein versus carbohydrates?

Some of them might.

I don't know why you're assuming they don't.

In your experience, do chefs have the kind of...

Some do, some don't.

Do chefs have the nutrition knowledge that you have?

I mean, you're an expert, of course, but do they have your threshold of knowledge that you think everyone should have?

I don't think so.

They have knowledge about cooking.

That's what they're doing, and they're trying to take what little science they know and apply it.

Would they be a better chef if they knew more of what you knew?

Possibly.

Possibly not, because so much of cooking is about taste and flavor and getting a feel for how you deal with the ingredients.

Do you concern yourself much with taste?

Yeah, she seems to be.

Absolutely.

You think people should eat moderately different things.

Of things that are delicious.

Yeah, so that they enjoy it.

She's not trying to get everyone to eat weird, like, paste that is neutral of calories.

I think healthy food should be absolutely delicious.

That's how you'll convince people.

Okay, but the stereotype is that the healthy food is nasty, and it's like taking your medicine.

I don't think that is anymore, actually.

I think that's changed.

Now, says the man who's a voice in Bob's Burgers.

That's not an argument.

It is.

At this moment, I'm invoking it as an argument.

Go.

My idea of a really great chef is somebody who can make vegetables absolutely delicious, so that's all you want to eat.

Oh, that's an interesting chef's challenge.

Take a meat eater and have them fall in love with vegetables.

Many, many chefs can rise to that challenge without any trouble at all.

It's true.

Just go to Blue Hill.

Yeah.

Blue Hill is not a bad place to start.

So you know about Blue Hill.

Oh, my God.

I've had carrots.

They start out with little tiny spiked carrots and radishes.

Remind me, Blue Hill has their own farm or something, is that right?

It's really delicious.

They control all their own vegetable products, if I remember that correctly.

Just because I'm on a cartoon with the word burger doesn't mean I eat only burgers.

I'm curious about something.

When people eat, different foods react to their systems differently.

People get indigestion.

You study the chemistry of people's reactions to food.

One of the things that's really fabulous about the human digestive system is that it can take anything and turn it into calories and nutrients.

Really anything.

There are some people who are sensitive to certain foods and have food allergies and other kinds of problems, but most people...

Even tofu?

Even tofu.

Just making sure.

Most people can take anything that used to be alive and that's edible and turn it into...

We're a calorie factory.

We're a calorie factory.

Wood?

Wood would be hard.

That's not suggestible.

I want to talk about eating wood in a minute.

For that, eating termites.

Exactly.

When we come back to StarTalk Radio, more on our show on nutrition.

Be right back.

We're back on StarTalk Radio.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, I got Eugene Mermin, and Professor Nestle, Nestle, the verb, or the net?

The verb!

The verb, excuse me, to Nestle, yes.

We're talking about nutrition, we're featuring my interview with Anthony Bourdain, and we were coming out talking about, could you eat wood?

Now, of course, termites eat wood, and they're having a field day doing so, because they have the digestive enzymes that can get calories out of wood.

They have bacteria in their intestines that allow them to do that.

We have bacteria in our intestines that can handle food fiber, but I don't think it handles wood very well.

Oh, okay.

But actually, it doesn't digest the fiber, it just passes it through, right?

It digests some of the fiber.

The bacteria can digest some of the fiber and turn it into little volatile fatty acids that get absorbed, et cetera, et cetera.

Okay, so we can eat, so lettuce, we can eat but not oak leaves.

It would be difficult.

It would be difficult.

Would it be poisonous or just unpleasant?

I don't know whether oak leaves are poisonous or not.

I'll tell you in a few days.

Yeah, why don't you do that?

Why don't you do that experiment and be sure and take notes?

No, but think about a future.

If there's a food shortage in the world and we managed a way to eat something first that allowed you to digest wood, because wood has calories in it, it's got energy, that's why you can burn it in a fireplace.

It's just not available to the human body as an energy source.

So we can imagine a day where you can digest wood.

And what would we do with all the jokes about food tasting like wood chips?

We would have to swap them out for another object or plant.

That's some food, right, some food that tastes like wood not on purpose.

Tastes like sawdust.

Yes, but just still wood.

In my interview with Anthony Bourdain, I talked about sort of the animal aspect of eating meat.

I mean, if you're gonna eat meat, it's a dead animal.

Okay, are you-

Agreed?

Agreed, okay.

Not a debatable topic, but what does it mean to eat something that's been completely, where its origin is completely concealed from you?

It's just a burger, it's just a-

Oh, I see, not like a farm to table kind of thing, but more of like just like buying a big pile of meat or finding it on the ground.

Why?

Would you go out and kill the animal if you knew that's what you were about to eat?

Let's find out what our conversation says.

I'd punch an animal out and murder it with my fist.

Maybe it's more true in America than in other places, but particularly in the carnivorous realm, we shield ourselves from the animal itself.

We buy a chicken, you don't see the feet.

You don't see the head.

It's just packaged and it's just a piece of meat.

Is that a good thing?

No, it's a terrible thing.

But why?

Why do you even care?

Okay, for a whole lot of reasons.

It's always good to know where your food came from.

It's only fair and just.

My friend, Fergus Henderson, was a pioneer of what's called the nose to tail movement.

He says, it's only polite, you know, if you're going to kill an animal or more often have an animal killed for your restaurant or your kitchen, it's only polite to eat as much of it as possible, to not waste.

People should understand where their food comes from, how it was raised, what the impact might be on society as a whole in that process.

But I think also just as sentient, caring people, a decent person would prefer that their animal is raised reasonably happy and killed with a minimum of cruelty.

But before everyone ordered their cowboy steak, if they said go outside, find the cow that you want us to slaughter, look it in the eye and pull this trigger and shoot it.

Honestly, I think that's an experience.

The more people who can do...

Cow with big eyelashes, you know.

It is something I've done.

When you travel this world, you meet your dinner frequently.

It's difficult.

When you've killed your first pig, you really start to abhor waste, disrespect to the ingredient.

I'm a lot more careful about how I cook my pork now.

You know, I understand.

Something died for that pork chop, okay?

I think you become a better citizen of the world and a more rounded person when you have seen that process and you've made some personal decisions as part of that.

But it is a life-changing thing and I think everyone should take part in it.

I think that's deep.

Do you agree?

Absolutely.

It's philosophically enriched outlook on the food that you confront.

Many people don't eat meat because they can't bear the idea of either raising animals for food or killing animals for food.

People who do eat meat, if they're thoughtful at all, have to come to terms with what that means.

And his coming to terms obviously is, he wants to respect.

It has a lot of respect in it.

I think that's a philosophical position that a lot of meat eaters have these days.

I want my meat raised humanely.

I know I'm going to be killing it, but I want it at least raised humanely.

My one little part of that, that I do for myself when I'm eating a shrimp, I eat the shrimp with the shell.

I think the shrimp gave its life.

I'm going to eat its shell as well.

Plus, it's chewable anyway.

It's not like a lobster shell, but also-

I eat the lobster shell because I'm a little better.

But also, when I cook a lobster, you know what I did?

I removed the claw rubber bands before I put it in the-

Oh yeah, doesn't everyone do that?

No, I don't think so.

Because I-

You would boil rubber bands with your food?

No, I want the lobster to have one last chance to bite me before it goes in.

Right, it's just a-

I guess I selfishly do the same thing because I don't want to boil a bunch of rubber bands.

So it's good that we're both good people, but me more selfish.

When we come back more about eating animals and some of them even carry diseases, when we come back to StarTalk Radio.

We are back, StarTalk Radio, Neil Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist.

I've got Eugene Mermin, comedian extraordinaire, love your stuff, Eugene, thank you, and Professor Marion Nestle.

Recently authored a book, this-

Why Calories Count.

Why Calories Count, From Science to Politics.

Awesome, and it's not your first book.

It's not your first rodeo.

You've been writing about this stuff for a while, so thanks for being on.

We're talking about nutrition, we're talking about food, talking about cooking, and in this segment, we're talking about slaughtering animals, some of which might have some disease that you want to avoid, and it includes interview clips that I conducted with Anthony Bourdain.

Let's get right to, at the top of this segment, my interview with Anthony Bourdain, where we just come out of talking about slaughtering animals, facing them in the eye, if you really want to appreciate what you're eating, and the fact that animals are a source of disease in the world.

Let's find out.

Some pathogens in our culture are directly traceable to viruses that hopped from animals that we either farm or eat, or how does that, does that scare you sometimes?

I'm thinking of avian flu or mad cow disease, or even AIDS with contact with the rest of the apes.

You know, I think exercising reasonable caution, in the same way you would if you travel around rural America, is a useful thing to do wherever you go.

I mean, the days when I would eat way as far out of my comfort zone, you know, as a daredevil, just so that I could tell friends that I drank, you know, live cobra blood, I don't do that anymore.

I guess I would advise people against.

I generally-

You used to do that.

Early on, I was so grateful to be traveling.

I didn't think this whole TV thing would last.

I'd never been anywhere.

So, yeah, when I was in Vietnam, I made sure to get the live, still-beating cobra heart and drink its blood.

Just so I figured when it all ended, six months later, at least I'd get a free beer telling that story, you know.

Long ago, changed the way I travel to be much more interested in the typical everyday thing.

I think if you use the same philosophy, people always ask me, do you get sick just stomach problems from traveling around eating all that street food?

Always ask yourself, is this how your average person eats?

Is the place busy?

It's generally not gonna be a concern.

If you're aware that avian flu has become a concern in the area, yeah, undercooked poultry is probably not gonna be a good idea.

You will have to think about those things.

If there's mad cow around, maybe calf's brains at a dodgy pub would not be your first option.

But I think if you familiarize yourself with what's going on as any cautious traveler should and don't take unreasonable risks, eating brains or spine in a mad cow area would be a bad idea.

They're just using common sense.

Yeah, just like they're not drinking the water in Russia from the top, you shouldn't either.

Do as the natives do.

So, Marion, how much attention do you give in your profession to not only nutrition of food, but the hazards that the eating of food can bring you when they're contaminated?

Oh, I actually have a book.

It's called Safe Food, the Politics of Food Safety.

Practicing safe food.

Yeah, that, yeah, safe food, exactly.

You know, E coli, botulism, FA.

Yeah, the Centers for Disease Control says 48,000 people in America get sick with food poisoning every year, and there's 125,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths.

Those are the standard figures.

So what do you do to avoid this?

I try to, when I'm traveling, I try to eat food that's been cooked.

Cook the food.

Cook the food.

Oh, cooking does wonders.

And never a sandwich that you find on the ground.

Well, not more than five seconds anyway.

So you cook the food, but also cooking removes some of the nutrients from food, isn't that right?

Yeah, but not seriously.

It'll kill a couple of the more dicey ones, like vitamin C and folate, but the others will be fine.

And you will be so much better off eating cooked food in places where the water's dirty, that you'll be grateful that you did.

Okay, but how about the pathogens that are not organic?

Like mad cow disease, isn't that just a folded protein or something?

Yeah, that's a folded protein.

That's pretty rare.

Hey, what's a folded protein?

Because everyone knows what that is.

It's a misfolded protein.

That makes it even worse.

What is that?

They're proteins in your body.

And this one happens to get into the brain, and it's bad, and it's folded wrong, and it makes others fold wrong too.

Uh-oh, and then your whole brain folds wrong, and what a folded brain is a dead brain.

That's what I say.

Yeah, it's bad.

It's bad.

You don't want to get that, but it's rare.

Yeah, you definitely don't want to get fold brain.

It's rare.

Okay, yeah, avoid the fold brain.

And it's something that cooking the food would not prevent.

No.

So avoid eating the brains of other animals.

Yes.

Okay.

When we come back to StarTalk Radio, more with my interview segments with Anthony Bourdain.

We're back on StarTalk Radio.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

And we're coming to our final segment on this program where we're featuring my interview with Anthony Bourdain.

And Professor, you've been commenting on this.

It's been great.

Just fleshing out what we're trying to explore, what it all means.

We came out of that segment talking about folded proteins.

You didn't know about a folded protein?

No, I'm willing to bet a lot of people misfolded.

Everybody knows about a perfectly folded protein.

It's the misfolded proteins that catch most of America.

It's the origami protein where they messed up the third standard form.

Which is a danger that is unlikely and can't be avoided by cooking.

Both of those things.

Great, so I'm not afraid.

Don't need animal violence.

How good is cooking at killing viruses as opposed to bacteria?

That'll do that too.

Cooking is really helpful if you're trying to kill bacteria and viruses.

So it could be one of the greatest contributors to our longevity.

It could.

And the fact that we started cooking food back when fire was tamed by cavemen.

Yes.

If you boil a person with a common cold, you will kill the common cold.

The question is how to find that perfect temperature before they die.

Well, that's kind of what your body does when it raises its temperature, is fighting bacterial infection.

So you are not completely crazy with that suggestion.

But I want to boil people to kill the virus.

But in fact, your body sometimes doesn't know how high to bring the body temperature and it can kill itself, right?

With a fever, yeah.

So there.

So I spoke with Anthony Bourdain about food in interesting, more exotic places, like food in space.

Rhode Island.

What astronauts eat.

Name one person who has ever been there.

Or if we are going to go to Mars or we are going to go some place, just food at high altitude.

Later this afternoon, I am going to be speaking with the space station astronauts and I am going to ask them, and I am inspired by this conversation, I am going to ask them, since it is an international space station, do they ever get together and swap each other's foods?

Well, they do.

I have spoken to some astronauts about this and it is really interesting what happens to the pallet at altitude in an outer space.

Apparently, if you have a stash of hot sauce, you are the go-to guy in outer space.

They crave spice and chili sauce, Tabasco, some kind of good spicy relish, seasonings.

Something to keep in mind, if our next mission to Mars, would you volunteer to be their chef?

Or to advise NASA on it?

Really be interested in going to Mars.

I cook and I had 28 years of it.

Somebody else can bring the food.

I will bring the hot sauce.

Well, you could be the spice man, I guess, how to make the food better.

Well, and it is, you know, airline food tastes so differently on the ground and at altitude.

And they have to completely reimagine it for what it's going to taste like up there.

So I think I'd be well, given my experience in Southeast Asia, I think I'd be a good choice for the Master of Condiments.

Marin, I'm intrigued by that.

I mean, I conducted that interview, but it didn't hit me until just now that if your taste buds, your brain taste bud connection changes according to altitude, you need a different cuisine at every stratum where people live.

Peony tastes so good eating in Aspen.

So, I mean, so what do you know is known about eating at altitude?

I don't think it's, I don't think the reasons for it are known.

It must have something to do with the loss of oxygen.

There's just less oxygen.

Less oxygen.

And even on an airplane, that is not pressurized to sea level.

It's pressurized at much lower, which puts less stress on the fuselage.

Because, if they pressurize the cabin at sea level pressure, then seals begin to give and it's, and I'm...

I thought at first you were like, you were talking about seal the animal.

No, no, no.

Sorry, sorry.

You don't know how planes work.

You think they're powered by seals.

Oh boy.

And so, and in the space station, the same thing.

So they might up the oxygen level to the same per breath, but the total air pressure is going to be less.

And we know you can survive in lower air pressure.

So that's fascinating.

But things don't taste as good and it's harder to boil water.

Yeah.

Well, it's so, well, harder to cook an egg.

You can boil the water.

You won't cook the egg because it boils at a lower temperature.

Yeah.

You wouldn't do that.

I mean, it sounds familiar.

I don't spend a lot of days boiling eggs in high altitudes, but sure, I've heard the thing about it.

Right.

So what happens is as you go to higher altitude, there's less air pressure on the surface of the water.

And so the water is trying to evaporate itself at sea level and it's fighting all these air molecules.

You go to lower air pressure, water is popping up willy-nilly.

And so the temperature of the water boils is lower.

Now you want to cook your three-minute egg.

The egg says, I'm ready for 212, but you only give me 180.

So your three-minute egg becomes a five-minute egg.

Sounds like you shouldn't be poaching eggs in space, but you should be making omelets on a nice hot pan, right?

Yeah, so we need a whole new cookbook for your various altitudes.

For the amount we're trying to get to Mars, we haven't thought about how we're going to cook on the way there.

You don't have to feed robots.

Yeah.

So we should re-engineer humans so that we can run on sunlight.

I would love a helmet that absorbs solar energy.

But then it's not as tasty.

The whole of food traditions of our world would be gone.

We've got to start wrapping this up.

Professor Nestle, thanks for coming.

And Eugene, and your book is out, just came out a few months ago.

Why calories count?

Why calories count?

I'm all over that.

And Eugene, are you going to read her book?

I am.

I'm actually totally excited to get your book.

You should have brought a free copy for me, but I'll get it on iTunes or something.

And that was great.

I want to publicly thank Anthony Bourdain again for granting us that interview.

And he was such a great guy.

I like your stuff a lot.

And he was so frank and honest.

And he was such a great guy.

That you've been listening to StarTalk Radio, brought to you in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

Give a shout out to NSF.

Oh, you're NIH people.

Excuse me.

NSF all the way.

I am Neil deGrasse Tyson, as always, bidding you farewell and to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron