June 9, 2018 7:13 pm

What to Expect When You Look Through a Telescope…and Why You Shouldn’t be Disappointed

Why seeing something gray and fuzzy is better than Hubble

Today’s guest blog post is by StarTalk intern Kirk Long. Kirk is majoring in astrophysics while minoring in applied mathematics and piano at Boise State University. He spends his summer weekends working at the largest public observatory in Idaho, the Bruneau Sand Dunes State Park Observatory, where he gives educational astronomy presentations and operates various large telescopes for the public. Kirk also helps run the StarTalk Snapchat (startalk-radio).

There’s been a resurgence of interest in science (especially space science) in the last few years, and with that growing excitement and popularity more and more people are visiting observatories and buying telescopes. I work at an observatory (that houses the largest public telescope in all of Idaho!) and I love showing people the night sky through our large telescopes, but I’ve found (anecdotally) that many people are often somewhat surprised when they don’t see a Hubble-esque image through the eyepiece.

Two images of the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51), one taken by Hubble and the other an example of what would be visible through a large (>10 inches in diameter) telescope with your eye. Left image credit: Clif Aschraft from https://www.wa2guf.org/; Right image credit: NASA/Hubble.

At the observatory I like to tell people that even if you went up into space and attached an eyepiece to the Hubble Space Telescope, you wouldn’t see an image like you see in the right picture above. You would certainly resolve more detail than you can here on Earth, and you might even see a hint of color, but on the whole it would still probably look more grayscale and closer to the image on the left. Why this discrepancy? In this case Hubble is creating a long exposure image consisting of a few hours of continuous observation. This doesn’t mean the picture is a lie — in fact if you could get close enough to the Whirlpool galaxy where it wasn’t so faint it probably would look remarkably similar to the Hubble image (although by the time you travelled there it would have noticeably rotated since it’s millions of light years away). That Hubble image was taken through optical wavelengths — so it is a true color image — the galaxy is just so far away that it requires a much longer exposure to collect enough data to show its true colors. Unfortunately, our biology has limited how long our brain waits before processing the data we receive through light landing on our retinas. We combine about 10-12 static images per second to generate our view of the world, and that means that we simply can’t store up enough data to stimulate the cones in our eyes (which see color) sufficiently, resulting in that grayscale image you see through the telescope. We don’t have great color night vision, but we actually have decent night vision in black and white, especially at our periphery. We have significantly more black and white detectors (rods) at the edges of our vision, and this probably evolved as a response to help us detect motion and respond to threats that weren’t coming straight at us. This quirk in our biology means that you’ll actually see most faint objects through a telescope better if you don’t look straight at them, but instead use a technique astronomers call “averted vision.” Since you’re probably not going to see much color anyway, why not get the most detail in black and white?

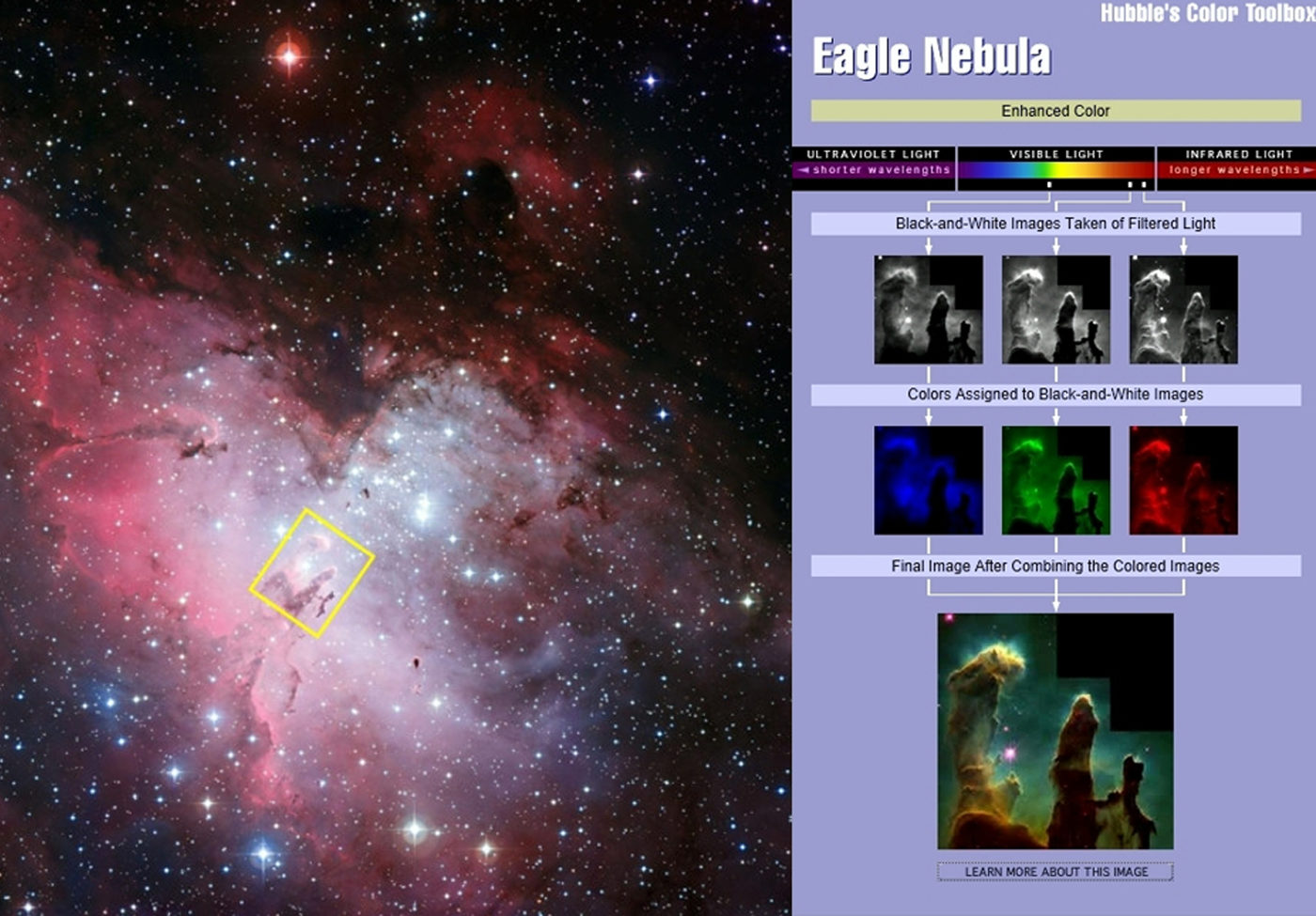

Another reason objects may look different through the telescope than you might have expected is that sometimes the most popular image of an object shared around the web isn’t a true color one, or it isn’t even taken in a wavelength of light our eyes can see! Take the below image comparison of the Eagle Nebula (famously visualized by Hubble as the “Pillars of Creation”) — the Hubble view (right) looks drastically different than the redder view (left) seen through an Earth-based telescope at the La Silla Observatory.

These two views of the Eagle Nebula are both in visible light, but one (the Hubble image) has been processed differently to bring out the differences in two contrasting reds (which correspond to two different elemental emissions) more drastically, as the graphic explains. Left image credit: ESA/La Silla Observatory. Right image credit: NASA/Hubble.

Astronomers do this kind of “enhanced coloring” to bring out small details that would otherwise be missed, and if they use visible light (like in the Eagle Nebula image) then the pictures are similar to what your eye would see in structure but not exactly what you would see in color. Sometimes images are made without using visible light at all, and the colors are simply added to represent the different structures or elements/compounds detected.

Not all objects are colorless, however, so don’t expect a night of entirely gray fuzzy blobs. Planets (especially the rings of Saturn and the belts on Jupiter) have a beautiful color to them, and although no telescope on Earth will let you see as clearly as a Hubble or Cassini image they can be closer than you might expect. Through our large telescope at the observatory (which is 25” in diameter) you can often see the split in Saturn’s rings (called the Cassini division) and even the Great Red Spot on Jupiter — if the conditions are clear and it happens to be on the right side of the planet. Stars also take on more distinctive and beautiful colors through the telescope, and some closer and brighter nebulas have some visible color to them as well (although this is again going to be much less than in a long-exposure Hubble image).

So why would you look through a telescope if the image you see won’t be as cool as a Hubble one? Seeing is believing, and there’s something special about interacting with the cosmos in person rather than through a screen. Although you won’t see as much detail as a Hubble image, when you look at many objects through the telescope you can see the same structure, and it’s not that big a stretch to imagine going from what you’re seeing to what Hubble sees. Some of the things you may see through a telescope may not look as visually impressive as Saturn’s rings or Jupiter’s cloud bands, but when you understand the context — that you’re looking at a structure millions of light years away, whose light has travelled across space and time to end its journey as a small stimulation on the back of your retina — that’s an incredibly profound experience. When that light hits your eye, the cosmos has just reached out to touch you, and that’s something you can’t get from a Hubble image (glorious though they may be). So don’t be disappointed when you see a gray fuzzy through the telescope, but instead I hope you feel a sense of deep connection to the universe. Astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience, but especially so when you do it with your own eye — it feels more authentic, almost as if you’re out there, rediscovering the wonders of the cosmos on your own. The best part? You don’t need to visit some fancy observatory to experience this version of the cosmic perspective (although you should). You can see the rings of Saturn, the bands and moons of Jupiter, and the beautifully brilliant moon all from your sidewalk (and they’re easy to find through a telescope, even a cheap one). Visit with a local astronomy club if you really want to get involved or don’t want to buy your own telescope yet — they often host star parties and invite the public to look through their equipment for free. So what are you waiting for? Get out there and explore!

Get the most out of StarTalk!

Ad-Free Audio Downloads

Priority Cosmic Queries

Patreon Exclusive AMAs

Signed Books from Neil

Live Streams with Neil

Learn the Meaning of Life

...and much more

Become a Patron

Become a Patron