August 19, 2017 10:00 pm

Want To Be the Smartest Person at Your Eclipse Party?

Four commonly asked questions about eclipses with some not so common answers.

Today’s guest blog post is by StarTalk intern Kirk Long. Kirk is majoring in astrophysics while minoring in applied mathematics and piano at Boise State University. He spends his weekends working at the largest public observatory in Idaho, the Bruneau Sand Dunes State Park Observatory, where he gives educational astronomy presentations and operates various large telescopes for the public.

In case you’ve been living under a rock the past few months, America is about to experience a truly awesome astronomical event — a total solar eclipse. The last time an eclipse crossed the entire continental United States like this was 1918, and it won’t happen again until 2045 (although there will be an annular eclipse that crosses in 2023 and another total one visible from some states in 2024). Total solar eclipses actually aren’t super rare — they occur somewhere on average every 18 months — but it is much rarer for them to pass through populated areas — such as most of America — like this. The path of totality is incredibly narrow — only about 70 miles wide in this case — and most of our planet is covered in water, thus most total eclipses end up passing through largely unpopulated areas of our planet. For many Americans, this eclipse could really be a once in a lifetime event, so if you live anywhere near the path of totality make sure you make the most of it. Wherever you end up in the path of totality, you’ll probably run into somebody — eclipses are a pretty big deal — so make sure you’re prepared to be the smartest person at your location by getting the answers to these four common questions.

The solar corona seen during totality. Photo Credit: S. Habbal, M. Druckmüller, and P. Aniol.

1: Where is the absolute best place to view the eclipse?

Short answer: Wherever it isn’t cloudy.

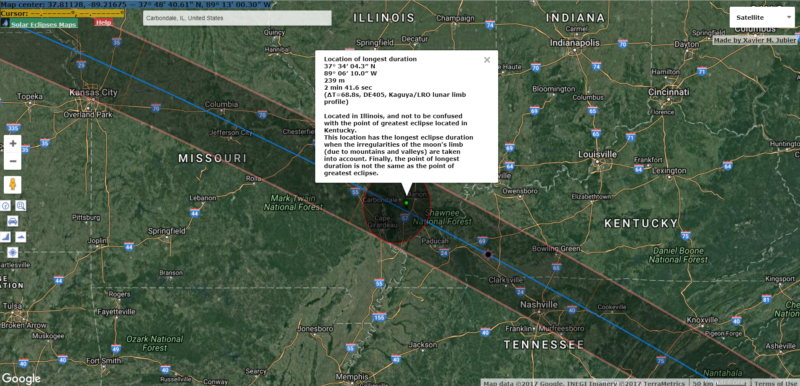

Longer explanation: By now you probably know that to get the full experience you need to be in what’s called the path of totality — that 70-mile-wide area where the moon totally occludes the Sun — but what a lot of websites don’t mention is that not all places within this path are created equal. The closer you are to the center, the longer your experience of totality will be. At the edge of the path you will only get a few seconds to experience this, whereas in the middle you can get more than two minutes. So, if you can, try to get as close to the center as possible. The reason behind this is pretty simple — in the middle of the path of totality basically the entirety of the moon’s shadow must pass over you, but if you’re at the edge only a sliver will. The moon’s shadow will cross the continent on average at about 1,800 miles per hour — doing some simple math you can find that crossing 70 miles takes about two and a half minutes whereas crossing 10 miles takes less than 30 seconds. Because the Earth is a sphere, however, the shadow moves fastest at the ends of the eclipse (as it “slips” onto/away from the surface) and slowest in the middle. During this eclipse, the place where the moon’s shadow will be moving the slowest — making the total experience longest — will be in Illinois, here. Hopkinsville, Kentucky has been getting a lot of media attention, however, because it’s closest to what we call “Greatest Eclipse”. Although it might make some intuitive sense that the point of Greatest Eclipse would be where it’s the longest, it’s not. Instead, Greatest Eclipse refers to where the shadow most closely lines up with Earth’s center. This is a little different from the point of Greatest Duration (Illinois) and differs because of the Earth’s oblateness and the relative motion of the shadow with respect to the equator. Here’s a NASA glossary that defines the two terms, and you can do some more googling if this difference really excites you. Really though, it doesn’t matter, as the difference is miniscule, and the best place to see the eclipse is wherever it’s not cloudy.

This point near Carbondale, IL is where the eclipse will be at its greatest duration. Thanks to Xavier M. Jubier for putting together this awesome interactive eclipse map. Click on image to visit interactive map.

2: How should I view the eclipse?

Short answer: Just get some of those glasses (if still haven’t gotten them) for $2, but take them off during totality!

Longer explanation: There are actually lots of cool ways to view the eclipse, and most of them don’t even involve those ridiculous looking solar glasses. Let’s get those out of the way, though. If you’re using the glasses you need to make sure they are the right ISO number (12312-2). You can find that number printed somewhere on the glasses, and if you can’t find it or they aren’t the correct number you might want to consider buying another pair just to be on the safe side. Regardless of where you are in the United States, you will at least see a partial eclipse, and using these glasses is a great way to watch the moon encroach upon the Sun without blinding yourself. Another great way to view the eclipse is with the use of shadows. If you can create some kind of device (as simple as two pieces of paper or a cardboard box with a small hole in it) that will cast the sun’s shadow, you will see the moon as it encroaches upon it in the shadow it projects. If you happen to be near some trees, watch how the shadows of their leaves behave — you might see an incredibly cool effect where lots of mini projections are scattered around. If you’re in the path of totality, when that moment comes and the Sun is totally hidden behind the moon, take off the glasses to see an incredible sight — the solar corona! You can literally see the Sun’s atmosphere with your own naked eye, and it’s beautiful to behold. If we’re lucky, there may be some large prominences, flares, or other interesting activity on the surface of the sun that will coincide with the eclipse, making the spectacle all the more spectacular. If you have binoculars or a small telescope you can use them without filters to safely view the solar corona up close — but this is only safe during totality, and do this at your own risk. If you are going to attempt to do this, be ready to put your filters back on even before totality is over — it’s not worth risking a better view at the expense of burning your retinas permanently. If you’ve got a solar filter for your telescope/binoculars/camera, you can also take great pictures throughout the event (which we would love to see). Finally, and this goes a little bit against what the news/internet has been saying to you lately, but you will not die from glancing at the Sun without protection. I don’t encourage it, but seriously, you won’t. You have probably glanced at the Sun before in your life and have yet to go blind or die, and this fact will not change during the eclipse. What is really terrible for your eyes is prolonged looking — please don’t do that — but a quick glance or two won’t kill you. Try at your own risk, of course, but just be sensible about it and please don’t call 911 if you accidentally look at the sun for a second.

This picture showcases the pinhole camera affect that tree leaves can create during an eclipse. Photo Credit & Copyright: E. Israel, from NASA APOD at https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap001225.html

3: What will I experience during totality?

Short answer: You need to see it to believe it — people have described it as “a religious experience” and “better than sex”, so make sure you take off those solar glasses for this part. Just remember to put them back on as totality is ending!

Long explanation: Totality brings with it some truly bizarre phenomena. You’ll notice that the temperature will drop quite rapidly — as much as 10-20 degrees Fahrenheit within just a few minutes. The sky will go dark — not quite night-time dark, but certainly twilight level dark, and dark enough to see bright stars/planets in the daytime sky. You’ll definitely be able to see Venus, and maybe Jupiter (it will be near the horizon if visible) and Mars (which is pretty faint). Mercury will be up at the time of the eclipse, but will probably be too dim to see with the unaided eye. You will also see a few brighter stars — stars you probably won’t see again for several months until winter rolls around. Astronomers assign a magnitude to objects in the night sky (the higher an object’s number the dimmer it is) and the darkening of totality will probably allow you to see what we call first magnitude objects — the predicted limiting visual magnitude during the eclipse will be a little greater than 1. Mars will have a magnitude of about 1.8 making it a bit of a stretch to see, Jupiter will be brighter at -1.8, and Venus will be brightest at -4 and should be easily visible even before totality starts (in fact you can even see Venus without an eclipse in the middle of the day if you know right where to look). You should also be able to see the stars Sirius (-1.4), Capella (0.1), Rigel (0.2), Procyon (0.4), Betelgeuse (0.4), Aldebaran (0.8), Pollux (1.1), and Regulus (1.3). As the Earth spins around the Sun we are exposed to different stars and constellations — although the stars themselves don’t really change position relative to Earth, our vantage point into the night sky does. Normally we wouldn’t see many of these stars again until winter rolls around, but because we will briefly eliminate the Sun’s excessive brightness we will be able to glimpse these constellations. This same darkening is what allows us to see the sun’s atmosphere — or corona. It’s always there, but most of the time it’s outshined by the rest of the sun to be seen. People have compared being in totality as akin to a religious experience, and there’s an entire group of people (called Eclipse Chasers or Umbraphiles) who are dedicated to experiencing totality as much as they possibly can. In the 1970’s a group of astronomers used the Concorde to chase the moon’s shadow, extending their time in totality to 74 minutes. Donald Liebenberg, an astronomy professor and one of the researchers aboard that flight, has seen 26 eclipses and holds the world-record for the longest duration spent in totality. The longest totality can ever last is about eight minutes (the length of totality depends on the how close the moon is to Earth, and thus how large it appears), so Liebenberg’s record will probably remain intact for the foreseeable future.

4: Why do eclipses happen, and why don’t they happen more often?

Short answer: Sometimes the moon goes in front of the Sun, other times it doesn’t.

Long answer: The Sun and the Moon don’t move in the same plane. There are two points in every lunar orbit where it lines up with the Sun, but to further complicate things most of the time when that happens the shadow cast by the Earth or the moon misses — at least partially — the other one (otherwise we would have a solar and lunar eclipse every month). The Earth and the moon both need to be in just the right places in their respective orbits for the shadows to line up, and this is called the line of nodes. Everything lines up every 346.6 days (an eclipse year) but there’s a catch: for an eclipse to happen it must be either a new moon (for a solar eclipse) or full moon (for a lunar eclipse). There are about 11.7 lunar months for every “eclipse year”, thus you can see how everything gets off and why eclipses are so rare. This means that, from one location, you would on average see a total lunar eclipse only once every three years and a total solar eclipse just once every 360 years. Partial or annular eclipses are more common, and on average Earth experiences two solar eclipses and two lunar eclipses each year — though many of these are “just” partial eclipses. There’s a more detailed physics explainer here if you want to learn more.

This diagram is a good visual to help understand the line of nodes concept, courtesy of the Astronomy Department at Ohio State University.

If money is no object and you can travel the world chasing the moon’s shadow (and thus the eclipse) you can see a total solar eclipse about once every 18 months and a lunar one once every six. Total solar eclipses are actually getting less frequent over time, because the moon is slowly moving away from the Earth as a result of tidal forces, and as it recedes from us it will appear smaller and smaller in the sky. If you’ve taken simple geometry you can do this math yourself (here’s a good worksheet, but I’ll give you the answer if you don’t want to do any math: about 563 million years from now the moon will be sufficiently far from us that it will no longer be able to totally block out the sun. At the same time, however, our Sun is expanding as it gets older — one day it will expand into a fiery ball large enough to envelop the Earth — meaning that over time it will appear larger to us. The precise rate of the sun’s expansion is hard to nail down (and it changes depending on what stage of its life it’s in) but this will probably take a few million years off our final number as well, putting it somewhere closer to 500 million years in the future. Moral of the story? Math is awesome and don’t take eclipses for granted.

One final fun fact: Earth is the only rocky planet that experiences solar eclipses — by some extraordinary coincidence our sun is about 400 times the size of the moon yet also 400 times further. Mercury and Venus don’t have moons, and the Martian moons are too small to ever totally block out the sun. If you could stand on the gas giants in the right places you would be able to see solar eclipses, as the Sun appears quite small and many have large moons, but the Earth is the only realistic planet in the solar system on which to experience one (without sinking/asphyxiating into the gas of one of the outer planets).

I hope this thorough eclipse briefing has left you overwhelmingly prepared for the big event a few days from now, but if you’ve got any other burning eclipse questions sound off in the comments and let us know. From all of us at StarTalk we’re wishing you clear skies, and remember, keep looking up — with those safety glasses of course!

Get the most out of StarTalk!

Ad-Free Audio Downloads

Priority Cosmic Queries

Patreon Exclusive AMAs

Signed Books from Neil

Live Streams with Neil

Learn the Meaning of Life

...and much more

Become a Patron

Become a Patron