October 7, 2017 12:57 pm

The Draconid Meteor Shower Peaks October 7th & 8th – A StarTalk Viewing Guide

Today’s guest blog post is by StarTalk intern Kirk Long. Kirk is majoring in astrophysics while minoring in applied mathematics and piano at Boise State University. He spends his weekends working at the largest public observatory in Idaho, the Bruneau Sand Dunes State Park Observatory, where he gives educational astronomy presentations and operates various large telescopes for the public.

Editor’s Note: This is an updated version to our post on the Draconids last year.

On the evenings of October 7th & 8th 2017, the Draconid meteor shower will reach its peak. Even in perfect viewing conditions, the Draconids usually only produce a few meteors an hour, but occasionally the Draconids have been known to erupt into an outpouring of meteors of hundreds or even thousands per hour. No such outburst is predicted for this year, but meteor showers are relatively hard to predict and it’s not impossible!

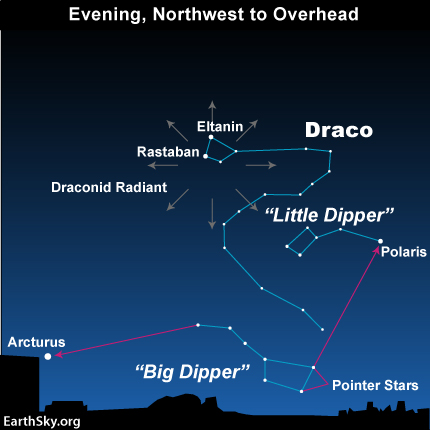

The Draconids are special among annual meteor showers for two reasons: Draconid meteors can be slow-moving and long-burning, and the constellation they appear to stream from, Draco, is highest in the sky in early evening. All meteor showers have a radiant, which is the point where — if you traced a meteor’s path backwards — the meteors appear to originate from. For most showers, this radiant is often highest in the sky after midnight, meaning that if you want to see the largest incidence of meteors you’ll have to sacrifice some sleep. The radiant for the Draconids is in the constellation Draco (see, sometimes astronomers make sense when we name things) and this constellation reaches its highest point in the sky in the early evening, but the drawback is that it’s best visible from northern latitudes, so if you live closer to the equator seeing the Draconids will pose an even greater challenge. The peak of the shower this year falls during the day (for those of us in the Western hemisphere) so the nights of both the 7th and the 8th should produce similar displays of meteors.

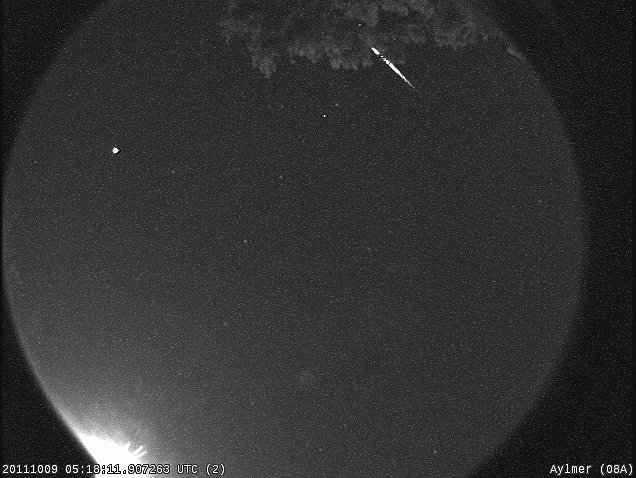

A Draconid disappears behind a tree in this image taken by a Canadian all sky camera. Image and caption courtesy of NASA, Credit: UWO Meteor Physics Group.

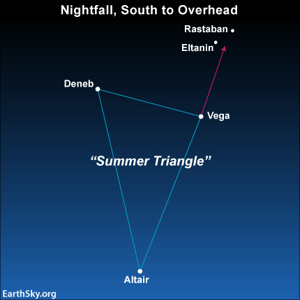

The most important factor in watching any meteor shower is having a dark, clear view — that’s easy for me here in Idaho, but it’s a bit more difficult for the StarTalk crew back East in New York, where the city (and the light) never sleeps. This year the moon will be in an unfortunately large waning gibbous phase, which means that no matter where you are you won’t be able to get a completely dark sky, but still try to get away from the city lights if you can. This large moon will rise shortly after sunset — use this nice tool to find moonrise and moonset times for your location — so your best bet to see the Draconids might be on the night of October 8th, where the moon will rise more than a half an hour later than it does on the 7th. Find a nice clearing where you can relax and stargaze for a few hours. Bring a reclining lawn chair or picnic blanket to lay down on so that you can gaze skywards comfortably, and look towards the constellation Draco in the night sky — hint: that’s why they’re called the Draconids. Draco looks like a dragon, and meteors will appear to radiate from near the dragon’s eyes.

Image courtesy of EarthSky.org in article linked to below.

EarthSky always has a great viewing guide complete with sky charts even a novice astronomer can easily utilize, so if you’re not sure how to find Draco in the night sky take a look at the guides below. Finding the radiant of the meteor shower can help, but it’s not critically important. If you can’t get to a dark enough sky you may not be able to see all of the stars in the constellation and it may be harder to find — but don’t give up! Although the meteors may appear to originate from Draco, they will streak across the sky in all directions, so just lay back, relax, and watch until you spot a few.

Image courtesy of EarthSky.org in article linked to above.

As meteors slam into our atmosphere they are superheated and vaporized, producing the brilliant colors we see in the night sky. The meteor’s color is determined by both the chemical composition of the meteor itself (think fireworks) and the ionization it creates in the atmosphere as it burns up.

This annual meteor shower occurs as a result of Earth passing through a debris field left behind by Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner. This shower is also sometimes called the Giacobinids, an homage to the comet’s original discoverer Michel Giacobini. As the comet gets closer to the sun and heats up, it sheds layers of itself into space, forming filaments of matter that the Earth later collides with. Meteors are the result of this debris burning up in our atmosphere. Much of this debris is relatively trivial in size — usually smaller than a pebble and weighing less than a gram or two. Most years we pass between the gaps in these filaments, interacting briefly with only the edge of one or two, but sometimes our orbit takes us head on into one of them, and those years produce spectacular shows. Astronomers can predict with relative accuracy when these outbursts will occur, but an encounter the comet had with Jupiter in the late 19th century altered its orbit, and thus where the filaments have been laid down since then, resulting in some uncertainty and the possibility each year of a surprise spectacle.

The next predicted Draconid outburst isn’t until 2019 (you can read more about Draconid outburst predictions and the methodology behind them here) but don’t let that discourage you. Some of the best shows have been predicted to be duds, and some of the most disappointing were predicted to be spectacular. Furthermore, any excuse to get outside and look up is a good one. Take a small telescope or pair of binoculars with you and observe the gibbous moon, or Saturn while you wait for meteors — both should be easy to see in the evening sky. We often hear about spectacular alignments, meteor showers, “supermoons,” and other astronomical phenomena, but really every night is an opportunity to witness a once-every-40,000-years occurrence of something or another — so get out there and look!

Get the most out of StarTalk!

Ad-Free Audio Downloads

Priority Cosmic Queries

Patreon Exclusive AMAs

Signed Books from Neil

Live Streams with Neil

Learn the Meaning of Life

...and much more

Become a Patron

Become a Patron