About This Episode

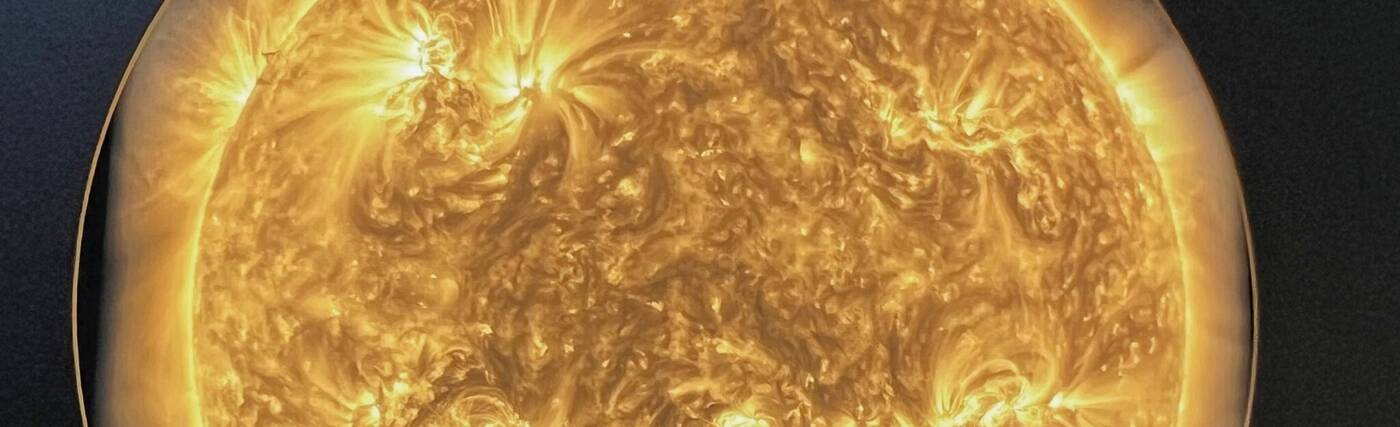

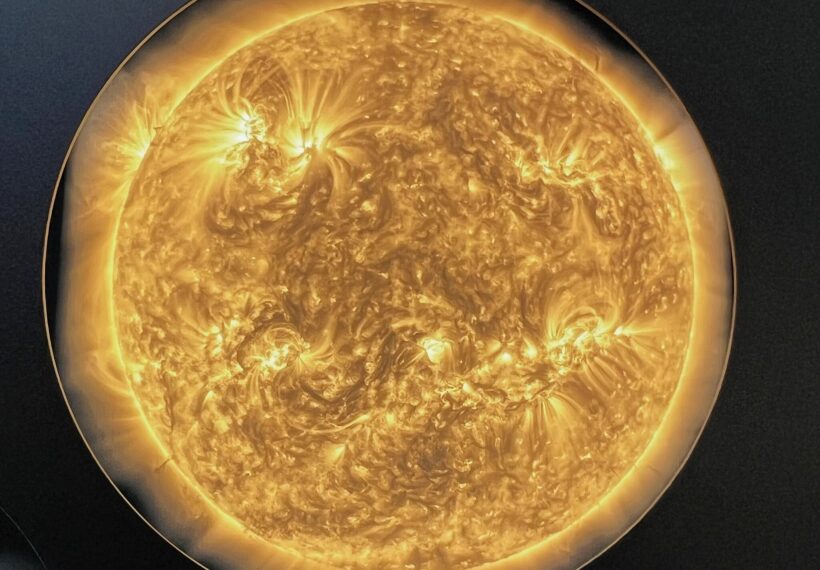

What’s the true color of the sun? Neil deGrasse Tyson and comic co-host Chuck Nice discuss things you thought you knew about the color of the Sun, the sound of weather, and why friction is our friend.

Neil explains why the Sun’s true color is white. You’ll learn how the atmosphere takes the Sun’s white light and turns it into something else. You’ll also learn why the blue sky is stolen sunlight. Neil gives us a photography lesson and tells us how photographers deal with different light. We investigate indoor vs. outdoor light. All that, plus, Neil explains why snow being white is evidence of the Sun’s white light.

We’ve all experienced our fair share of weather. But have we listened to it? Neil and Chuck investigate the acoustic effects in climactic phenomena. Find out about the shape of lightning and how that influences the sound of thunder. We explore “constructive” and “destructive” interference. Neil explains why we feel some sounds more than we hear them. And, Neil gives us a science trick to help figure out how far you are from the approaching storm. We explore why snow is nature’s sound-proofing. Then, we debate if you can hear an aurora. All that, plus, we investigate hail and Neil shares why “down pause” is one of his favorite weather terms.

Why do we need friction? Usually we talk about friction as a bad thing, slowing things down, heating things up. Neil explains why without friction, life as we know it would not be possible. Discover how every mode of transportation requires friction. Are there any that don’t require friction? We investigate the lack of friction in space and how we push against the earth. Do we move the earth or does the earth only move us? Could we speed up the rotation of the earth if every person ran in the same direction at the same time? Could you push something heavy if you had no friction? We explore momentum and ancient ideas about friction. What did Aristotle and Galileo think about physics? Where did the idea behind friction come from? Plus, find out why spacecraft erupt in flames as they reenter Earth’s atmosphere.

Thanks to our Patrons Jorge Aguirre, C&C Angeli, Len Brandis, Alan Parker, Aaron Ivey, AA-ron or just “AI”, MD Bartlett, Nox, Nicholas Crayford, Adam Collins, Deep Patel, RAHIM THERIOT, Dan Abrams, Dan Thomas, Tig, Gloria Michelle Shirley, Mike Horvath, Daniel Brannon, Tonieh Ellis, Camila Von Malice, Kat, Nickolas Madeo, Marcus Phelps, Daniela Eneva, AndyF, Paul Purington, Paul, Mark Fowler, Thomas Freridge, Corey Ferrell, Mo O, Jacob Johnson, Matt Newcomb, Vladimir Antonovich, Steffen Sommers, Joan Morrissey, yared ts, Danielle Seitz, Edmond Fondahn, Blythe Lucas, Richard Adam, Bryant McFayden, Nayah Sci Fi, Lissett Lamboy, John Lujan, Marie Mckenna, Kaustav Chakravarthy, Hannah Bradley, Joshua Jones, EVA, Gail Knapp, Gavin Dunagan, Decoy, Athena Ozanich, Dakota Barron, William Gibson, Eleanor Dewitt, Tru Shadow, MorningSong, Matt Delashaw, Angela Woods, Eric Gorohoff, Zakary Tackett, Carmen Fragapane, Kristián Žuffa, Michael Dunsavage, Mark Bradshaw, Kelsey Harkness-Jones, Mark Rose, Brent, Mohammed Hamdy, Baz, Andrew Stevens, Rachel Jacobsen, Rick Dawson, Tibor Szabo, Raven Knight, McMarklar, Chris Cummings, FromLongIsland, Wendy Parsons, Denise Asmus, Brad, JimPP, Lauren Cooper, Juan Jove, Brent Bailey, Watts Wire Extension Cords, Graham, sean aley, NotAnotherMike, Robert Currier, Steve Vanspall, Alex Nuss, Thomas PASCAL, Antonín Karásek, Mikayla Trousdale, MC, 22 Simulations, Kasey Marsland, and Stevie for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTHey, everybody in the StarTalk-iverse.

We’ve got yet another Things You Thought You Knew episode.

This time, Chuck and I get into The Color of the Sun, Weather Acoustics, and Friction.

Check it out.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Welcome to the Explainer Zone.

Yes, the Explainer Zone.

Yeah, yeah, not the Twilight Zone.

That’s the Twilight Zone.

We are confused at the end.

The Explainer Zone.

Where you come out knowing more than you get when you win.

Knowing some stuff.

Right.

And so I think there’s no end to this, just so you know.

Good.

I will be calling you forever.

All right.

So I want to talk about the sun, the color of the sun.

Okay.

All right.

Well, you know me, I don’t see color.

You don’t see color?

Sorry, we’re already done here.

So here’s the thing.

If you were a school child and to draw a scene and you want to put the sun in the sky, what crayon do you reach for?

Well, I was a very depressed child, so black.

Okay.

No, you knew about black holes back then.

Yes, exactly.

No.

Oh, it’s always a big yellow ball.

It’s always yellow.

And this notion has been with us since childhood, that the sun is yellow.

And that’s not true.

It’s not even close to being true.

And so, yeah, I’m sorry, I, you know, I don’t want to…

Are you sad about this?

Are there any kids watching, please?

You might want to leave the room right now, because we’re not sure if there’s a Crayola available for you to draw your little scenes with the house and the grass and the little tulip.

Here’s the thing.

The sun in broad daylight is too bright to look at, all right, without risking damaging your eyes.

Unless, of course, you have perfect eyes.

Okay.

So, you don’t do it, all right?

So, when is the time most people ever find themselves looking directly at the sun?

When is that?

Well, the only times I’ve ever done it is sunset and sunrise.

Sunset and sunrise.

Exactly, exactly.

So, not only do we have the yellow crayon in our crayon box from childhood, anytime we actually ever find ourselves looking at the sun, either on purpose or by accident, it’s low on the horizon, the sun is rising or setting, and it has a deep yellow color.

Sometimes it’s so deep, it can be red, the amber into red.

Yes.

So, and we know the sun isn’t red.

Of course, it’s not red.

We know that’s not the goal.

Now, this isn’t Krypton.

It’s not Krypton.

It was a red sun.

So you know, intuitively, it’s not red, but somehow you don’t know intuitively that it’s also not yellow.

Okay?

What color is the sun?

It is white.

Now, come on, man.

Why you gotta do that?

White.

See?

What?

Just like everything else.

All of a sudden.

Chuck, not everything is a race commentary.

You know what?

Seriously, we’ve got to…

Must we whitewash all of history including the sun?

Really?

So, yeah.

So, it’s not yellow.

Okay.

It’s not yellow.

Now, I can give you evidence of this if you need evidence, but I’m simply saying that as the sun gets…

Let’s look at earth and there’s the atmosphere wrapped around the earth.

If the sun is directly overhead or anywhere near directly overhead, it goes to sort of, let’s call that one thickness of atmosphere, okay, top to bottom.

As the sun gets lower and lower in the sky, the path of light through the atmosphere is longer, okay?

Because now you got…

There’s that angle through it.

And the lower the sun gets on the sky, the more and more atmosphere it has to pass through.

And in fact, you can calculate how many equivalent atmospheres it went through.

Okay?

And you just need a little bit of trigonometry.

It’s a simple calculation.

And if it’s low on the horizon, it goes through five, six, ten equivalent atmospheres.

Gotcha.

When it’s low on the horizon.

So whatever the atmosphere is doing to the sun when it’s high up overhead, it’s doing it ten times that and more when it goes lower on the horizon.

Okay.

So let’s see what the atmosphere is doing when the sun is overhead.

In comes white light.

Okay.

And white light is composed of colors, as Isaac Newton demonstrated.

All the colors of the rainbow.

Red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, if you must, violet.

Violet.

Okay.

So in it comes particles in earth’s atmosphere that happen to be the same size as the wavelength of light of the blue side of the spectrum, the blue, indigo, purple, violet side of the spectrum.

Those particles preferentially scatter the blue out of the sunlight.

Preferentially scatters it.

So it subtracts away a little bit, just a little bit.

All right?

The rest of the light makes it all the way to earth’s surface.

But some of the blue gets scattered and that’s why we have a blue sky.

Nice.

The blue sky is stolen sunlight that would have otherwise passed straight through.

Look at that.

Right.

Because the sky is really clear, right?

Okay.

So now watch.

How beautiful is that?

Now let’s have the sun get a little lower in the sky.

Well, there will be more of this going on.

Okay.

More of the sky.

That’s why on cloudless days into sunset, the sun gets deeper and deeper and deeper blue.

The bluest sky.

That’s why sky blue is light blue.

Right.

All right.

You want to talk about Sirius right home to mama blue is the blue sky that surrounds the twilight curtain of the sunset.

Now you’re talking blue.

Right.

Okay.

So, so much blue is taken out that we now, Roy G.

Biv, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and he took out blue, indigo, violet.

What’s left?

Red, orange, yellow, green.

Okay.

If you add those colors together, you’re going to get an amber sun.

And depending on how many particles there are, you’ll get a red sun or you’ll get a simple yellow sun on the horizon.

And so you now look at, so, oh, we have a yellow star.

Look, it’s yellow.

No, it’s the atmosphere made it yellow.

Okay.

It’s lying to you.

And if you, so here’s what you do.

Broad daylight, if there’s thin Sirius clouds, okay, so it’s safer to look up to the sun.

Look up to the sun in the middle of the day.

Is it yellow?

No, no.

It is white.

This is very disturbing.

It’s very, very disturbing.

Because the clouds themselves don’t change the color of the sun.

It just dims it.

So you look at a slightly dimmer sun behind the thin clouds as they pass.

So it’s not yellow.

It’s not yellow.

Not only that, consider the following, all right?

Now this takes a little extra thinking.

Put your thinking cap on.

Okay.

And in another explainer, we address this.

But now there’s a different reason for it.

If I have a sheet of paper and it’s white, that means light reflected of it, from it, is an even mixture, an equal mixture of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet.

All those colors together in optics makes white.

Don’t tell this to an artist.

Right.

It doesn’t work on the ease of it.

No, it’s just the opposite in art.

It’s just the opposite.

You don’t get black, but you’ll get like sludge.

You’ll get sludge, right.

All right.

So the fact that the page is white means all of those colors of light are hitting that page.

So that when they reflect up, you see white.

Okay.

So a white light illuminating a white piece of paper shows up to you as a white piece of paper.

There you go.

Okay.

Now, white reflects all colors.

Let me put a red gel in front of the light.

Now look at the paper.

What color is it?

It’s red.

It’s red.

Kind of pinkish, but yeah.

That’s right.

So it reflects all colors, but now it’s only getting red.

It’s going to reflect the red.

It reflects all colors.

The page is red.

To your eye.

Let’s put a blue gel.

What happens to the page?

The page is blue.

Same thing.

Yeah.

Okay.

So if the sun were yellow, then snow would be yellow.

Which by the way, sometimes snow is yellow and it’s not from the sun.

And whatever you do, whatever you do, stay away.

Don’t eat the yellow snow.

Stay away from that snow.

The fact that snow looks white is evidence that it’s being illuminated by white light.

That white light is either sunlight or a moonlight.

That’s right, which is also a reflection of sunlight.

It’s just reflected sunlight.

There you go.

This is so disturbing.

So disturbing.

So I’m just trying to be honest.

I’m just trying to put it out there.

And by the way, let me take…

You want to go up a notch?

Are you ready to go up a notch on this?

I don’t know if I’m ready to go up a notch.

I don’t think you’re ready.

Okay.

So white is the sun.

Hate where this is going already.

Relative to incandescent bulbs.

Right.

Okay.

Your kids will have no memory of incandescent bulbs, but old timers, if you’re over 25, you’re an old timer, you remember bulbs that would get hot when you put them in.

It was a bulb with a little piece of wire in it.

Okay.

The wire used to light up.

That sounds like a Ken Burns special.

The guy on the porch.

Right.

I remember the days when it had a bulb with a little piece of wire.

Now that wire would light up and get hot.

But we pulled the switch.

We pulled the switch and it gave off light.

Now first, it should look like magic.

Okay, we gotta put you on the list of the next Ken Burns special, The Origin of the Lightbulb.

So, all right, so, where was it?

I forgot what it was.

Yeah, you’re saying incandescent bulbs.

Incandescent bulbs.

Incandescent bulbs, when you turn them on, the temperature of the filament is not as high as the temperature of the surface of the sun.

And so, the higher the temperature, the more full that spectrum becomes.

So, if you looked at the spectrum of a bulb in your house, an incandescent bulb, it’s very weak in the blue section.

There’s some blue there, which is why blue still looks blue under that light.

But the blue is very weak under an incandescent light bulb.

Okay?

So, if you bring out film that needs the full complement of blue, and you take a picture under incandescent lights, everything is going to be red.

That film, if it needed the blue, is called daylight film.

This is why there was a difference.

Again, I’m only talking to old timers here.

There was indoor film and tungsten film and outdoor film.

And the outdoor film was color balanced to get the entire spectrum of the sunlight.

If you took indoor film and put it outside, that indoor film is too sensitive to blue because it’s making up for the feeble blue coming out of a bulb, and it goes out and it’s getting all the blue it ever wanted.

If you have indoor film and took a picture outside, everything looks blue because it was hypersensitive to blue, and the sun has plenty of it.

Okay, so to a photographer, sunlight is blue.

It’s highly blue.

And they have to correct for that if they’re going from indoors to outdoors.

They have to redo the color balance on a white sheet of paper to account for the difference between indoor lighting and outdoor lighting.

Now, here’s where they all got it wrong, but they’re not going to change it because they’re deep into it.

You ready?

Now we have the blending of science and technology with art.

You ready?

Here it is.

If an artist draws an Arctic scene, what color is prevalent?

White.

And what color?

Blue.

Blue.

Right.

If an artist draws Dante’s hell, what color is prevalent?

Red and orange.

Red and orange.

Okay.

So emotionally, we think of blue as cold and red as hot.

Photographers will tell you we need to reduce the temperature of the light, which means make it colder emotionally.

But the only way to do that is to get more blue in it, which means upping the temperature of the tungsten that they have shining on you or to put more blue into it.

And in the old days, that meant a hotter light bulb.

So they said, we need a cooler scene.

They had to have a hotter bulb.

We need a warmer scene.

They had to have a colder bulb to do that.

Wow.

And that language is still embedded in that entire profession.

Yep.

That is true.

The opposites.

And they meet in the middle and they deal with it.

The opposites of art and technology and science and the physics of life.

So I got one for you, how about acoustic effects in climactic phenomenon?

Really?

Yeah, yeah, I just thought about that.

Okay, it sounds like something that, if somebody said to me at a cocktail party, I’d be like, I gotta get a drink, I’ll be right back.

But they will come back, because it’s intriguing enough, but they gotta get, they gotta pray.

But first, they gotta get prepped.

They’re chemically prepped for it.

All right.

Let’s start out with thunder and lightning, for example.

So lightning, in its path between the ground and the clouds, or between a cloud and the cloud, never goes in a straight line, because it’s finding the path of least resistance the entire time.

Unknown to you, this is what it’s doing.

And then when you see the lightning strike, it is already a predetermined path between one point and another.

All right.

Now it turns out the sound of lightning is simply the shockwave of rapidly heated air by the bolt of electricity moving through the air, which is extremely hot.

Right.

Okay, it’s thousands of degrees.

But what matters is that it is the air is some other temperature, and then it is instantaneously made extremely hot.

This creates an expanding shockwave that we hear as thunder.

Okay.

Now, because the path of the lightning is not straight, there are kinks in the root.

So each segment of that kinky lightning has its own generated shockwave.

Okay.

Right.

So now, you have multiple kinks generating their shockwaves, and you can have constructive and destructive interference of competing shockwaves.

That makes so much sense.

We just…

Oh, go ahead.

Okay.

Okay.

Oh, this is good.

Okay.

So our researchers have found the lightning at 50,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

50,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Okay.

That’s hot.

Okay.

All right.

So now watch.

So with these different segments, that’s why a single lightning bolt…

And by the way, the lightning bolt is not all the same distance from you, okay?

The parts that are a little closer that were on the ground.

If it’s cloud to cloud, the part directly above you is closer than farther away.

So the sound will hit you at different times.

But it’s one generated event.

Right.

So that’s why the lightning can go…

Snap, crackle, pop.

Okay.

That’s why it’s not just one acoustic experience.

It is a highly…

I love your thunder.

You like my thunder?

We have to isolate.

No.

What just happened?

If I see that on a meme, I will kick you.

Oh my God.

I am so…

I will kick your ass.

That is so going to be a meme.

So, here’s the lightning, and it’s because of the acoustical configuration of the lightning bolt itself.

That is wonderful.

I’m serious.

That is so great because one of my favorite things in the world is to hear thunder, but not the rumbling thunder, the thunder that sounds as if it is tearing the sky.

Yeah, because that is okay.

I’m getting there.

That’s my next point.

Okay.

So, I’m just simply accounting for…

By the way, constructive and destructive interference, if you’re not familiar with that.

So sound travels in waves, so it crests and troughs, and this is a pressure wave through the air.

It hits your eardrum, your eardrum vibrates.

We interpret that as sound.

So does your body too.

By the way, there’s certain frequencies of sound that are longer…

Sorry, there’s certain wavelengths of sound that are longer than what will fit in your eardrum.

So your eardrum will have a hard time communicating it to your brain, but the length of the wavelength is about the size of your chest cavity.

That’s the low frequency long wavelength.

And so there are some sounds that you feel more than you hear.

Oots, oots, oots, oots, oots, oots, oots, oots, oots.

That’s the rhythm section of the beat.

What do they call the beat?

The beat boppers?

What do they call them?

Beat boppers, yes.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Boy, if I heard lightning starting to do that, it was like, whoa, there is a god.

That god is a DJ.

So here’s what happens.

The lightning sound is a huge cacophony of frequencies of sound energy.

Okay.

High frequency, low frequency.

But here’s the problem.

High frequency doesn’t travel very far.

It’s easily disrupted.

It can easily lose its energy relative to the energy that it started with.

And if high frequency sound loses its energy, it becomes lower frequency sounds.

So the farther away you are from a lightning strike, the lower is the total cacophony of frequencies that reach you.

Aha.

So lightning on the horizon is…

Okay, if you have a pet dog, they hear that and they notice that.

And they might start trembling and you don’t even know why, because that frequency is below what you can hear.

The dogs hear it.

Alright.

As the storm gets closer and closer, the higher frequencies become more and more part of what you hear.

And if you hear a lightning strike, would that sound like it’s ripping the fabric of the space-time continuum?

It meant it hits your house.

Alright.

So, that’s what’s going on there.

Sound moves through air at about 700 miles an hour, plus or minus, depends on the density of the air.

But I like easy math.

So let’s just declare that the sound is moving at 600 miles an hour.

Okay.

600 miles an hour is the speed of sound in air.

How far does sound go in a minute?

Well, that’s 600 divided by 60.

That’s how far?

I don’t know.

You just set up the verbal math problem, then that computed.

No, that’s not allowed.

I don’t know, 120 miles.

So if it’s 600 miles an hour, and you divide by 60 minutes, then sound will move 10 miles in a minute.

So if sound moves 10 miles in a minute, how many seconds does it take the sound to move one mile?

Ten seconds.

Six seconds, right?

Six seconds.

So it moves a mile every six seconds so that after a minute, it moves 10 miles and after an hour, it moves 600 miles.

Right.

So basically, if you want to know how far away the rain is from you, time, get the time difference between when you see a lightning strike and when you hear it.

So you see the flash and then you count 1,001, 1,000 Mississippi, 2,003.

So if it’s five seconds, let’s say, that’s almost six seconds.

So the storm is about a mile away.

A mile away.

Yeah, about a mile away.

And so, and the real number is 700 miles an hour.

So it’s, you know, you make a small adjustment, but you get the basic idea.

Okay.

Sound moves a mile every six seconds.

And so just for your habits.

And if you hear the thunder and it never gets closer than that, the rain is not headed towards you.

Don’t worry about it.

Go home, go back to sleep.

Nice.

If that time delay keeps getting shorter and shorter and shorter, watch out, watch out.

You’re about to lose your house.

Yeah.

Dorothy, you’re not in Kansas anymore.

There you go.

Nice.

So a couple of other acoustic things.

So for example, a snowflake is very, is highly variegated, right?

It’s got six sides.

It’s got a lot of texture.

And if you have snow that’s descending and it’s just softly landing on blankets of the on the surface, okay?

Now you have sound.

Generally when you hear someone from a distance, you are relying on the fact that the sound is bouncing off the pavement, off the walls.

We don’t think often about this, but reflected sound is a big part of how we interact with our world around us.

All right.

If you have snow everywhere, the surface of the snow is not rigid.

It’s not highly reflective.

In fact, it’s highly absorbent.

So particularly for city people know this.

If all of a sudden the city gets quiet and you don’t hear anything, look out the window, chances are of snowing.

Nice.

Because the sound of the cars and all the normal sounds that reach you by reflecting off of steel and glass and concrete and cement is no longer reflecting.

It’s all muffled.

Yeah.

And so the song, the Christmas song Silent Night, Holy Night, whatever other reasons you want to think of it as a silent night, if it has just snowed, guaranteed to be more silent than it otherwise would have ever been.

Snow is nature’s soundproofing.

And they are soundproofing.

Now, when you’re walking on snow, okay.

As opposed to walking on sunshine.

Okay.

So it’s just snowed and you’re walking on it, okay.

And that will normally be a silent exercise, okay, because you’re just pressing down snowflakes because they landed softly.

And now you’re just sort of compressing them.

Fine.

If it’s colder, I forgot the temperatures.

If it’s colder than like 25 degrees, 20, low 20s, it was definitely if it’s in the teens or lower.

If you then step on the snow, okay, the snow says, I will not yield under your boot print.

I’m going to hold my shape because it is cold enough that we are all solid and rigid.

And what happens?

The snow crunches.

Yeah.

Then you crunch on snow.

So if you’re filming a movie or if you’re observing a scene and you hear people crunching on the snow, guarantee the temperatures in the low 20s are in the teens.

Or there’s a guy in a booth with some cornflakes and he’s just matching the sound to the people walking.

The sound studios have all those, the sound effects in there.

Right.

So that’s why snow crunches at cold temperatures and does not crunch at warmer temperatures.

By the way, at the warmer temperatures, your pressure is enough to melt the snow, okay, to bring it immediately below the freezing point.

That’s a whole other StarTalk explainers that we’ve done.

What the ice will do under pressure.

Under pressure.

Yeah.

So these are some interesting sort of sound things to look out for when this happens.

Now, it has been rumored that aurora, that you can hear aurora.

And I’m not convinced of that.

Really?

Yeah, yeah.

Because it happens, you know, it happens 50,000 feet up, you know, 10 miles away and farther up in the atmosphere where the atmosphere is really thin.

It is electrical.

So it could be that it’s creating other electrical phenomenon in your environment.

But to say that you heard sound that comes from that high, I’m not convinced of that.

I don’t believe.

But people say it.

So it’s worth it.

I bet it is.

It sings.

Yeah.

Yeah.

It’s worth investigating.

I think so.

Yeah.

Yeah.

And so let me think.

Any other sounds you heard in weather that you wonder about?

I mean, you know, aside from the fact that my uncle used to like to make his own sounds and then blame it on me while we were walking in the cold other than that.

And here’s another one.

You know, the sound of hail hitting, right?

These are basically, these are like marbles falling out of the sky.

I know what that sound is.

That is the sound of a call to the insurance adjustment.

So people say, you know, you know, when do you get hailed most?

You get it in the summertime, right?

That’s weird.

Ice falling out of the sky in the summertime.

Well, it’s a reminder that the sun is not heating the air.

The air is transparent to sunlight.

That’s why you can see the sun from earth’s surface through the air.

And so the South to Los Angeles, Los Angeles and Beijing and Mexico City.

Right.

So those are inversion layers that so they’re climatically susceptible to trapping smog.

Both those three years, you know, they’re all in basins or Santiago, Chile as well.

So here’s what happens.

The sun heats the ground.

The ground heats the air.

All right.

But if you go high above the ground, it gets very, very cold very, very quickly, no matter the time of year.

All right.

But in the summertime, you have the most ground heating.

And so you have the most unstable air columns.

So the biggest, thickest, juiciest cumulonimbus clouds, which we all learned about in elementary school, the big puffy ones, though you find those in the summer term.

And you look at them and you think the cloud is just sitting there.

But if you look for long enough, you will see that it is roiling.

And in the roiling, there is very highly unstable air rising within it.

The more unstable the air is in the upwardly rising columns, the harder it is for whatever is hanging out in there to fall out of the cloud.

Because it’s kept buoyant by these upwardly moving air columns.

So, you first nucleate a little droplet of ice.

It wants to fall.

I say, no, you’re not.

And it comes back out, and it nucleates with more moisture.

Because what is a cloud?

It’s a big pocket of moisture.

Okay, droplets, droplets, water droplets.

It gathers more moisture.

And ah, no, you’re not.

And it keeps doing this.

It keeps doing this until the frozen ball says, you ain’t holding me this time.

And that’s why all of hail is about the same size.

Because it had to get to that size to overcome the highly unstable air columns that were supporting it.

And so the more turbulent is the air, the louder they will be when they hit the ground.

And then there it is.

And we always reference the size of hail to some other object, which I find interesting.

No one says, I saw softball size hail.

It was baseball sized hail.

I’ve never seen anybody talk about hail sized golf balls.

Right.

Maybe it’s obvious why, but I don’t know.

But anyhow, so Chuck, that’s a little bit of the sound of weather.

I love it.

So, so very cool.

Oh, and one other thing.

One last thing.

You ever been driving a car and it’s raining, and it’s raining the whole time you’re driving?

And then you come under an overpass.

And it’s silent.

Yes.

Okay, just silent.

That’s an interesting phenomena, because what your brain had done was create the sound of rain as the normal, so that when you go under the underpass, it’s the absence of rain that you take notice of.

See, and that happens in my everyday life, where the normal sound is a house full of silt.

Running around.

And when you step out the house, you say, what was that?

When you step out into silence, you wonder, you look around.

So silent out here.

What’s relevant?

What happened?

And, oh my God, did we move to the country?

So there’s a word I’ve seen, and it hasn’t caught on, but I think it should.

It’s the sound of the absence of rain under an overpass.

Okay?

And it’s called a downpour.

Oh, instead of a downpour.

Downpour, downpour, that’s lovely.

I will leave you with that.

Friction.

Oh my goodness.

Yes.

Friction.

Friction.

Now, friction, usually when people talk about friction, it’s bad, all right?

Bring out the WD-40.

It’s squeaking, it’s friction.

And friction burn.

Friction burn, right, right, right.

But let me tell you, without friction, life as we know it would not be possible.

Friction is your friend.

See, I have lots of missing skin on my knees that would bed to differ.

So friction, I mean, just think about it.

If you just sort of put your elbow on the table, right, and you just rest it there, and then you want to listen to me.

If there was no friction, you would just slide off the table.

There’d be nothing keeping your elbow there.

That’s why I stopped wearing silk shirts.

And let’s say you wanted to drive your car.

You need the friction between your tires and the road so that you will move forward.

If there were zero friction between your car and the road, the wheels would just spin and nothing would happen.

You would go nowhere.

You wouldn’t be able to start the car, to move the car, slow down the car, stop the car, or even steer the car.

All of that requires friction.

To walk, to walk, you put a foot down, there is friction there, you press back, and your next foot moves forward in advance of it.

That required friction.

This is why on slippery ice where there is no friction, you can’t walk, you can’t run.

And you say, this is bad, put me back on regular ground.

What you’re really pleading for is, give me some friction.

Right.

You don’t say that because friction has a bad name.

And what do you do when it’s cold out and you’re not wearing gloves?

What do you do?

Hands get hot.

I just realized it’s cold in my house.

Okay.

So you do that, okay.

Friction is your friend.

Oh, that’s nice.

So we’ll do a whole other thing on friction becoming heat.

That’s a whole other explainer that needs its own time for that.

Oh, but a friction can help get you warm.

All right.

So the only thing that really does not use friction is rockets.

All other transportation requires friction.

Oh, bicycles, trains, planes in order to take off, OK?

Oh, my goodness.

That’s right.

All of this requires friction.

The planes needed to take off.

Oh, so with a rocket, however, by the way, it’s why rockets work in space where there’s no air, there’s nothing rubbing against anything else.

It sends material out the back and it recoils forward.

Right.

So all rockets that are accelerating are losing mass in order to do it in a recoil.

Whereas you don’t have to lose mass to do it.

You just have to press against the earth.

Right.

Well, Newton told us for every action is an equal and opposite reaction.

So if you are standstill and you start moving forward, actually something has to start moving backwards.

And it’s communicated that way through friction.

So what happens?

You move forward with a certain momentum.

What are you pushing against?

The ground.

The ground.

The ground has to move backwards.

And it does.

So the entire earth is responding to the fact that you moved in one direction.

Okay.

Oh, man.

Can we all get together, every human being, just in one group, and start running in one direction?

Will we speed up the earth?

Yes.

Or slow it down, depending on which direction.

And it has to be due east or due west.

Correct.

Due east or?

Yes.

What?

So if you…

So if everyone lined up, okay, and started running due east, okay, so that will sort of spin.

Wait, which way are we turning?

We’re turning this way.

So you have to run and run due west.

And if everybody does that with their scurrying feet, you will speed up the rotation of the earth.

What?

That is the response of the earth to you propelling yourself forward by way of friction connecting you to the earth itself.

It’s true with cars.

It’s true with everything.

Now, I once did a calculation, and I said, let’s get our most powerful rocket engines, bench mount them at the equator where you have sort of maximum torque on the earth.

And can we use that to either speed up or slow down the earth?

And I did the math on that, and it’s hopeless.

Okay.

It’s like a gnat flying full speed into the side of an elephant, and believing the elephant even took notice.

Okay.

Sorry, confident, very confident gnat.

Very confident gnat.

So very confident gnat.

In fact, it’s less than that.

So, but, but-

Take that, Dumbo.

What I’m saying is the momentum that we all gave each other by putting ourselves into motion, you can write down that number.

Momentum is your mass times your velocity that you gave yourself.

Okay?

Earth’s rotation increase or decrease will have changed by exactly that same amount of momentum, so that they both cancel.

Because you started out both not moving relative to each other.

So if one thing starts moving, the other thing has to recoil the other way, so that they balance out.

That’s Physics 101.

So if you go forward, Earth goes backwards by the exact same total momentum.

But Earth has so much mass relative to all the mass of the humans, that your momentum, which is mass times velocity, that’s the only quantity that has to be the same.

All right?

So all we humans run forward and add up all our mass and get all our velocities, add it all up, and we’ve got this hunkering Earth with this really large mass, and it gets a teeny-litty-bitty velocity to balance us out.

So you don’t notice it.

But you can calculate what that effect is, and it is real.

It is real.

Wow.

Excellent.

And it’s friction.

It’s all friction.

So I just want you to think of friction as a good thing.

It’s more good than bad.

One thing friction does is it slows down things that were put into motion.

And Aristotle, not really understanding friction, Aristotle got most of his physics wrong, by the way.

He’s not a champ.

He’s no hero in physics and astrophysics.

Thank God he had philosophy.

Philosophers like him.

And he did important things, but there’s stuff he could have really checked and he didn’t.

And so it’s before experimental philosophy kicked in as a approach to thinking philosophy.

And so the experimental philosophers, Bacon had a whole book just on experiments that he said he conducted, but there’s like a thousand experiments in it.

And that’s what all he’d be doing every day for the rest of his life.

So I don’t think he did them all, but it’s a, there’s a book that he collected them.

And so he, and Galileo, do the experiment if you have an idea.

Okay, so.

Because otherwise, and no disrespect, Aristotle, you’re just bullshit.

You’re just, you’re just thinking stuff up that you think should be true, because it makes sense to you.

We can all do that.

In the armchair.

So he said, things in motion tend to come to rest.

Okay, so, that’s true, right?

All right, but Galileo said, wait a minute, if I wax the track, you know, I have a thing, I roll it down the hill and it stops like here.

Now I make it smoother.

It stops a little farther away.

Make it even smoother.

It starts even farther away.

And he said, wait a minute, what would happen if there was no friction on this track?

Where will it stop?

And he concluded that things in motion will tend to stay.

And he fed Newton’s things in motion tend to stay in motion.

It’s the opposite of Aristotle unless acted on by an outside force.

Look at that.

And so Galileo was the bridge between Aristotle and Newton and doing the experiments by waxing the track, making it ever more smooth, reducing the friction coming.

That enabled him to establish a fundamental truth about nature, going beyond just what your life experience is.

Look at that.

Galileo, the Mr.

Miyagi of physics.

Who knew?

Wax off.

So I just want you to appreciate friction.

You know, I will not.

No.

I still can’t get my head around liking friction.

But it is necessary.

Without friction, everything would just be floating, would be gliding.

Sliding around.

Sliding around.

You sit on a couch, the couch would just slide back.

By the way, you could push very heavy things.

If there’s a freight train, I don’t care what it weighed.

If it’s on frictionless tracks, let’s say it’s a maglev frictionless track and you have a little handle, just take it and start pulling.

So you can put a force on it and yes, it’s way more mass than you are, so the velocity will be small, but it’ll have some velocity.

Right.

So you can just start pushing it.

And this is why those strongmen competitions, okay, where they pull with it in the old days, they pull the train with their teeth.

Okay.

It’s because trains are on steel rolling wheels on steel tracks, which has very low friction.

Okay.

If you took it off the tracks and let it sit there in the mud and then haven’t tried to tug the train, that ain’t happening.

That’s kind of funny though.

You could pull things that have wheels on them because wheels have very low friction in the transmission of the movement of that object to the ground.

Because you’re not dragging it on the ground.

Right.

But the wheel itself still needs a little bit of friction in order to not spin out.

That’s all.

That’s so cool.

Oh, you know, I have to say, I will never think of friction in the same way.

One last thing.

When astronauts reenter the atmosphere and they have that, you know, the burning phase, you know, yes, the flames and the thing.

All right.

We say, oh my gosh, will they survive?

This is bad.

How could?

No, you need that.

The astronauts coming out of orbit are going 17,000 miles an hour, and they didn’t bring fuel to break.

Oh, okay, because all they would have to do, all they would have to do, we don’t do this, but what they could do is bring enough fuel.

While you’re in orbit at 17,000 miles an hour, because that’s orbital speed, turn their ship around and fire it backwards.

Right.

That will slow you down.

And you keep doing that until you have zero velocity, and then you just drop out of the sky.

If you drop out of the sky, you’re not going to be burning up.

Because what’s burning up is the kinetic energy of having gone 17,000 miles an hour in the first place.

I saw a movie, I think it was one of these Mars movies, one of the earlier ones that came and went, where there’s something happening on a platform, and the guy falls off the platform, but it’s a stable platform up there above the ground.

And as he falls, you see him just burn up.

It’s like, no!

No!

The act of falling through the atmosphere alone is not what burns you up.

It’s the fact that you are going from 17,000 miles an hour to zero.

And where does all the kinetic energy go?

There is friction between you and the air molecules passing across your surface.

There’s also shock waves that communicate as you’re going faster than the speed of sound.

Shock waves take all this energy that you have and convert it into heat.

And then the heat dissipates.

And then you fall down out of the sky alive because you have special heat shields that protect you.

Uh huh.

There you go.

And before we perfected the tiles that we used on the shuttle, we had the heat shield was astronauts.

They weren’t really shields.

A shield is something that protects you.

We call them shields, but that’s not what they were.

You know what they were?

They were like onion layers of burnable material.

Oh, so they just burned off.

Exactly.

But you had to go through enough of them to get to the crispy center.

Where the astronauts are.

Where the astronauts are.

So it turns out coming out of orbit, you need more of these layers than when you come back from the moon.

So coming back from the moon, they just make that layer thicker.

And then it ablates, and it heats, it burns off, and goes out.

That takes the heat away.

And each, as these layers go.

So it’s a very blunt, effective heat shield.

But it’s really a shield that dissolves away in the heat.

All of that, the friction, the shock waves, and that allows you to not have to take fuel in order to slow down using fuel, because you’re basically aerobraking.

Sweet.

That’s what reentry is.

It’s a form of aerobraking.

That is fascinating.

Friction is your friend.

That’s all I’m trying to tell you, Chuck.

Every astronaut loves friction.

Otherwise, they can’t come home.

Can’t come home.

Or you need fuel to slow down.

That’s all I’m saying.

You want to exploit what you got.

And so you should say, great, they’re burning up their heat shields.

That’s a good thing.

Sweet.

All right.

All right.

I’m liking it.

Chuck, friction is your friend.

All right.

I got a new friend today.

That makes one.

It makes one, one, one friend.

Chuck and his one friend.

I got my one friend.

All right.

Neil deGrasse Tyson here.

Your personal astrophysicist.

Keep looking up.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron