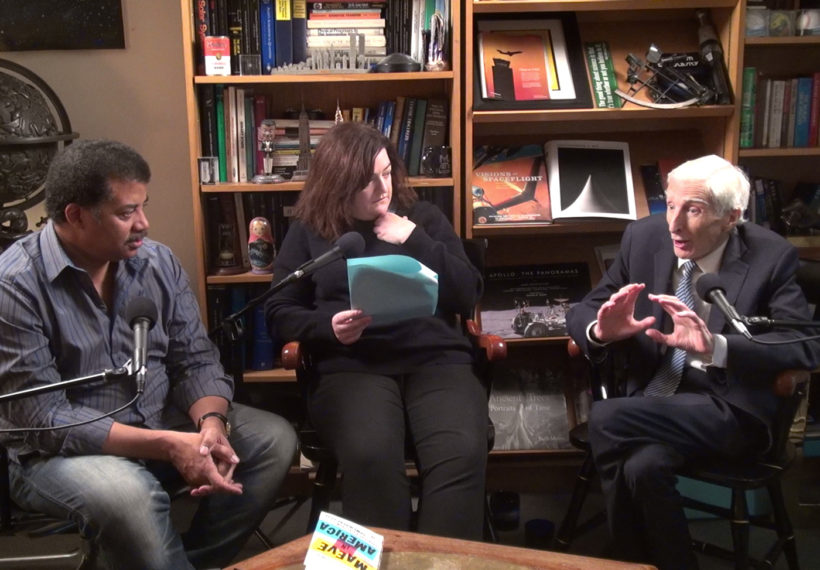

What does the future hold for humanity? What will be at stake? Are we on a path of destruction or enlightenment? On this episode of StarTalk Radio, Neil deGrasse Tyson investigates what the future might bring with comic co-host Maeve Higgins and Sir Martin Rees, astrophysicist, cosmologist, Astronomer Royal of the United Kingdom since 1995, and both the former Master of Trinity College at Cambridge and former President of the Royal Society (a position held by Sir Isaac Newton himself), and author of On The Future: Prospects for Humanity.

To start, you’ll hear how Neil and Martin’s friendship blossomed many years ago as we dive into Martin’s history as one of the world’s most prominent astrophysicists. Find out why people should listen to astrophysicists, not futurists, when trying to predict the future. Ponder what we may be able to predict with some certainty by 2050. Learn why we should keep our minds open to science fiction. Discover how science fiction can be used to make sure a dystopic future doesn’t happen. Martin tells us his fears about the misuse of bio- and cyber-tech and how each could undermine governments – and already have begun to influence the world.

Next, we dive into fan-submitted Cosmic Queries. We discuss whether or not a globally unified science organization is in our future, and how science functions as a global culture already. You’ll hear if scientists are ever competitive and secretive with information. We debate how future generations will react to the current generations’ handling of the climate crisis, and whether certain climate disasters have to occur in order for people to understand the seriousness of climate change. You’ll find out if space travel will be accessible for everyone in the future. Learn why it’s dangerous to think human problems can be solved by Martian colonization. Explore the future of space travel: will it be a private or public venture? Will NASA become a spaceport service for private vessels? Will NASA become obsolete? Who will be the first people on Mars? How important is science literacy for moving us into the future? What might be the next “big thing” in science – could it be dark energy? You’ll learn more about the Large Hadron Collider and if some of the science being created at CERN can protect us from solar radiation when traveling through space. Martin tells us about witnessing the discovery of a pulsar firsthand. Finally, we question whether the Golden Record was a good idea, and whether interdimensional travel more plausible than faster than light travel. All that, plus, Sir Martin gives us his thoughts on where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re headed.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. This is StarTalk. I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist. And tonight, my co-host is the inimitable Maeve Higgins, Maeve!...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

And tonight, my co-host is the inimitable Maeve Higgins, Maeve!

Thank you.

Oh, we're doing an elbow bump.

An elbow, yeah, you have to get around the microphone.

Is that so that you don't get like my germs?

You get elbow germs only.

I keep my elbows so clean.

Welcome back.

Thank you, I'm so happy to be here.

I don't think you've been back since you published your book, Maeve in America.

Now, just to, I blurbed this book.

You did.

Will you allow me to read the blurb?

Please.

I'm gonna read the blurb.

Yeah, I asked you, I said, Neil, please read this book.

You said, must I?

And you agreed to read it, so thank you.

So here's the blurb.

Until space aliens land in America, Maeve Higgins from Ireland is the next best thing.

She offers fresh and insightful perspectives from a faraway place on all we take for granted.

So good luck on that.

Thank you, I'm green like an alien.

Yeah.

Because we all know aliens are green, yes.

You heard it here first.

Tonight we are talking about the future of humanity.

And there aren't many people you want to do that with because most people don't know what the hell they're talking about.

But tonight we got one of the deepest thinkers on this subject.

We brought in Sir Martin Rees, a friend and colleague of mine from way back.

Sir Martin, welcome to StarTalk.

Great to be here with you, Neil.

Excellent, thanks for doing this.

You just came out with a book called On the Future.

And you wrote a blurb for it.

Yes, I got two for one here.

You have a side hustle.

How much did you pay to write your book?

Well, he's in very good company.

You can see the other people who have written blurbs.

Four pages worth of them, yes.

We have Elon Musk.

Elon Musk.

Elon Musk.

Governor Brown.

Governor Brown.

So I'm going to read my blurb if I may, okay?

From climate change to biotech to artificial intelligence, science sits at the center of nearly all decisions that civilization confronts to assure its own survival.

Martin Rees has created a primer on these issues and what we can do about them so that the next generation will think of us not as reckless custodians of their inheritance but as brilliant shepherds of their birthright.

That was great.

That makes people actually want to read the book.

So Martin, let me just give people just a little background.

I don't know if I've told anyone this publicly, but when I was a graduate student, you were eminent now and like forever.

You've been eminent in my field.

I was an astrophysicist at the University of Cambridge in England, where the original Cambridge was from.

Proto Cambridge.

Proto, starter Cambridge.

And as a graduate student at one of our sort of society conferences, I think I had a poster paper where you're not sort of far enough or long for them to let you give a talk.

So you just put your paper up on a poster and you wait for people to come by.

It's a passive delivery of your science.

And you came up to my paper and you looked at it and you asked me questions about it and you didn't have to do that.

And I felt that my future as a participating scientist was blessed, if you will, by your presence.

And so I just want to thank you.

I don't know how often you do that, but I just want to thank you because what may have been little for you was big for me at the time.

Well, great.

And now it's the other way around.

It's great for me to be with you today.

But then, of course, you were at Princeton University and you gave this wonderful course, which I didn't attend, but I read the book about it.

Oh, you did?

Yes.

Ultimately, I post-doc'd at Princeton, then I talked there.

But so just want to thank you for all the work you've done.

And you're like, he's like the last gentleman in the world.

Oh, yes.

Well, that's really important and that's really good for science too, because I think ethics and morals are needed in science.

It's just, it's, so I'm just saying, they don't make them like him anymore.

And you had a good book, but for you, the smaller your books are, the better they sell.

Yeah, it turns out people don't like to read, I think, at the end of the day.

Yeah, your tweets though.

Oh, yeah, yeah.

So now it's in the, it's tweets.

People read, you know, 200 character tweets.

I love the image of you.

Were you like in a row of graduate students and then Sir Rees is just kind of walking by and you're like, pick me.

Like the bachelor.

I'm sure he spoke to more graduate students than me on that day.

So let me just go down your sort of four line bio here.

Astronomer Royal, this is, didn't Edmund Halley have this or something?

Well, that's right.

Of course, it was the person who ran the Grange Observatory, but that became a museum from the 1960s onwards when, of course, we could have telescopes under clear skies elsewhere.

But they kept the title.

I see.

And so I have this just as a title.

And there's only one Astronomer Royal?

Only one, yes.

But there were no duties.

It's just honorary.

And I like to say the duties are so exiguous, I can do them posthumous.

I need never give up.

Also, I'm sure somebody else would like the role.

You can take it with you to the afterlife.

So, Astronomer Royal, that's so...

My day job is as a professor at Cambridge.

A professor at Cambridge.

So, you were previously master at Trinity College, director for the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge University, and you are currently a professor, we have similar ranks as we do here, professor of astronomy at University of Cambridge.

And a member of the UK House of Lords, so I'm a bit of a politician too.

I got the member of the UK House of Lords and former president of the Royal Society.

Which is like your National Academy.

National Academy, good, okay.

Our National Academy is where scientists elect the most eminent among us.

So it's a peer-voted representation of who and what we are internationally, and to the government especially.

I see, and the House of Lords is like the...

I'm getting there, I'm getting there.

Okay, so now, so previously you were knighted.

That's when you became Sir Martin Rees.

Right, yes.

And you actually stand there in front of the Queen, and she holds a sword where she could tap your shoulder or cut your head off, depending on her motion.

She did the former.

But then I got an upgrade to the House of Lords.

Okay, so once you're knighted, then you are Sir.

Yes, yes.

Okay, now in the old days, that became hereditary, right?

Was that not true anymore?

That's not true.

There was something called a baronet, which was hereditary, yeah.

But Lords were hereditary, and they're not anymore.

Okay.

So you have to earn us.

Well, in some sense, you have to earn us.

If you look at most of them, they haven't really earned.

And I would say that's it.

Oh, he's talking smack about himself.

So being in the House of Lords is a privilege, but not an honor.

Oh, interesting distinction.

I had thought about separating those two.

And so don't you have to have some plot of land that you govern?

You don't really, I mean, you have to designate a sort of area, and I picked Ludlow, which is the hometown in the west of England where I grew up.

Oh, OK, so you're Lord of that patch of land?

Yeah, but they don't recognize me.

It doesn't mean anything, though.

Can you just knock into any of the houses?

No, no, no, no, no.

I'm hungry.

Don't you know who I am?

No rights there, but for historical reasons, you have to have a name of a place associated with you.

Well, thank you for not choosing Ireland.

So you're Lord of Ludlow.

Yes.

OK, very cool.

I like the alliteration there.

And that doesn't mean I'm a Luddite.

Very good.

Lord of Luddow, not a Luddite.

Not a Luddite.

On his iPhone as we speak, no, you're not.

So this is not your first rodeo.

On the future, you've got our Cosmic Habitat.

Just six numbers.

That was one of my favorites, because people didn't know how dependent so much of our understanding of the universe was on just a few measurements that we were actively making then and still.

And our final hour.

I didn't read our final hour.

That sounds, that doesn't sound happy.

Well, it was entitled in England, Our Final Century, question mark.

They took the question mark off, and you Americans retitled it Our Final Hour, because you like instant gratification.

And the reverse.

We like fast food, fast.

That's incredible.

That's so dramatic.

But that was in fact a precursor of the present book.

And it really addresses some of the big questions about what's happening this century and why this century is special, even among the 45 million centuries where the earth existed.

Well, let me lead off with a question here, because why should someone listen to an astrophysicist why not a futurist?

Why is your insight deeper or more accurate than a futurist might offer us in possibly writing the same titled book?

Well, I don't recognize futurist as a real profession.

Yeah, they're still irritating.

Yes, I don't even...

But obviously...

Depends on what they predict.

I'm not an astrologer, I have no crystal ball, so we can't make reliable predictions.

Typical Gemini.

But there's some predictions, but all I would say is that I can do a better job than an economist can do.

Is it because you have knowledge of the laws of physics and how they shape what is possible and what is not possible?

Well, I think so.

I mean, just to take two examples from my book.

We can't predict the very far future, but we can predict, I think you'd agree, that by 2050, the world will be more crowded, nine billion people, and the world will be warmer.

CO2 emissions.

Okay, but do we need you for that, though?

I mean, come on now.

No, we don't.

No, no, no, but certainly people haven't listened, so the more people who can repeat these things and say we need to prepare for them, the better.

But of course, what we can't predict, whether you're a futurist or anything else, is technology that far ahead, because the smartphone would have seen magic 25 years ago and the social implications of social media and all that.

And therefore, when we look to 2050 and beyond, we've got to keep our minds at least ajar to what now seems science fiction.

And I discuss things, but accept that they are very uncertain.

I definitely look to astrophysicists for future guidance because of the scope that you have.

Well, we do think in deep time.

I mean, we think deep backwards and forwards.

Well, I think the one special thing is that, you know, most people now, unless they're fundamentalists or in parts of the Islamic world, are aware of the four billion years of the past that's led to our emergence, our evolution.

And there's plenty of people here in America who are still...

That's what he's saying.

Yes, but I mean, even educated people who accept evolution, they tend to think that we humans are the end point, the culmination.

But I think as astronomers, we can't take that view because we know that the future is at least as long.

The Earth will exist for another six billion years before the Sun dies, and the universe may go on expanding forever.

And I like to quote Woody Allen, who said, eternity is very long, especially towards the end.

So we should think of ourselves as a stage.

And the theme of my book is that we are a very important transition stage because two things are going to happen this century.

One is spreading beyond the Earth for the first time, and the other, perhaps, is...

You mean colonizing other locations in space.

Yes.

And another thing is, of course, having the power to, as it were, redesign ourselves by genetic techniques and cyborg techniques and interfaces with the electronics.

Like more than just hair transplants.

Yeah, that's right.

And so that is something which is special this century and which makes the future more unpredictable, but more fascinating.

So this is a crucial century.

And of course, those exciting possibilities should be in our minds.

But the downside is that because of this powerful technology, there are extra risks which we didn't have in the past.

So here's a question I've been meaning to ask you ever since I read this book.

There's a famous quote from Ray Bradbury.

When asked, I'm paraphrasing.

I was afraid you were going to quote Woody Allen too.

When, I'm paraphrasing.

But when asked, why do you write such dystopian stories about our future?

Is this what you think will happen to us?

And he says, no.

I write these stories so that you know to avoid them.

And so let me ask you.

There are restorative forces in society that tell me that, I think, we will never land where dystopic storytellers tell us.

You know, remember in Soylent Green, you know, we're eating.

I mean, just pick any movie, any movie where there's a descent of humanity to some rock bottom.

Aren't there forces that will restore it?

Well, we hope so.

And of course, Ray Bradbury is right, that if we are aware of the bad things that can happen, that's a motivation to try and prevent them.

And I think one of the-

But historians might disagree, because the whole time they're telling us about awful things that happened in the past, and we're just like, all right, keep it down over there.

The things that actually did happen in the past.

Well, that's right.

But I think there's a set of concerns, which I highlight in my book, about the downside of ever more powerful technology.

And we are aware of two types of concern.

One is the pressures we're putting on the human habitat by the growing population, more demanding of energy and resources.

So we're risking some tipping points that cause lots of extinctions and make the...

Possibly our own extinction.

Possibly our own extinction, yeah.

So that's one class.

But the other type of threat is, because even a few people are now empowered to create by error or by design, a consequence that could cascade globally.

We are familiar with what cyber attacks could do, and they're going to get more serious.

And also, similar concerns about misuse of biotech.

And so those are two technologies which are getting very powerful.

And in fact, in Cambridge, we've set up a group to study these issues, because even though a huge number of people are studying small risks like plane crashes, carcinogens in food, low radiation doses, et cetera, not very many people are thinking about these low probability but catastrophic consequence risks.

And in our group in Cambridge, we feel that if we can reduce the probability of those by one part in a thousand, we've earned our keep because the stakes are so high.

They must be the most fun people at a dinner party.

When everyone's like, you know, I don't know if this chicken is cooked.

And they're like, well, I can tell you there's something coming for all of us.

Don't worry about the chicken.

Where we can have to give good plots to these dystopian authors.

Yes, totally.

I see.

So they should mine your deliberations and come up with stories for future movies.

Yes, yes.

And of course, we do plenty of scenarios and the university like Cambridge can convene experts to decide what is complete science fiction and what is a serious threat.

But you have experts in all the different branches of human investigation that can weigh in.

Yes, and I think they have an obligation to weigh in, in my opinion, because the experts are very often wrong, but they're more likely to be able to see a threat before the average person.

And your single biggest threat that you think of is what?

Single biggest?

Well, in the short term, I worry about bio and cyber.

Because I think they're going to make governance very difficult because there'll be the tension between privacy, liberty and security.

Yes, an eternal tension, actually, yeah.

But it's getting worse because, you know, I like to say the global village will have its village idiots and they will have a global range.

So we can't be so benign and tolerant as they were in the past.

The local village idiots can influence the wall.

I mean, the world.

The power that they're allowed.

They're not just like...

Well, I mean, this is true, obviously, by cyber already.

And I think with biotechnology being so widely dispersed, I mean, biohacking is even a student sport, then we have to worry about this.

Yes, sport, it became a sport.

Yeah, yes.

And, you know, we say we can regulate these things, but regulating these techniques globally is as hopeless as regulating the drug laws globally or the tax laws globally.

And not even the Americans have managed to do those.

And your biggest concern 50, 100 years out?

Well, I worry then about the environmental effects.

And of course, we don't know how powerful computers and AI will be then, and we've got to cope with that.

Okay, well, we gotta take a break, and when we come back, we will take questions from our fan base that are all directed on this very subject.

And Maeve, you've got the questions?

I've got the questions.

You haven't seen them yet?

Neither of us have seen them, but they're all going to him.

When StarTalk returns...

And I bluff my way.

This is actually a Cosmic Queries edition of StarTalk with our special guest, Sir Lord Martin Rees.

We're back on StarTalk Cosmic Queries Edition on the future, Prospects for Humanity, which happens to be the exact title of Sir Martin Rees' book, a long time friend and colleague of mine in astrophysics from the University of Cambridge.

And I've got with me as my co-host, Maeve.

Yes.

Maeve, you've got questions.

I've got the questions.

The question is, does he have the answers?

Let's see.

Let's find out.

Okay, who do we have?

Okay, this comes from Facebook.

Kato's Clover asks, do you think that one day we'll have a worldwide united science and or space organization?

Oh, that's a good one.

Well, of course, science is a sort of global culture.

Protons and proteins are the same everywhere in the world.

And so that's why science is valuable for straddling political divides and divides of faith.

We can be in common.

And of course, sometimes we have to work together because we need big bits of equipment.

Telescopes are not funded by a single country, et cetera.

So you're not taking turns to use telescopes in some cases?

Yeah, we do.

We do.

And we're very polite about it.

You're not like, shove over.

We don't fight it on the line.

But the Europeans are building the world's biggest telescope, 39-meter diameter.

And we work together to fund that sort of thing.

But I think also the challenges of the application of science for health and energy and all that need to be tackled globally, as does climate change.

Has there been a problem in the past, though, with scientists not sharing information and the competitive nature?

Well, I mean, I think obviously sometimes there's competition to be first.

But I think scientists are far more cooperative than most people.

They share the culture and they realize that it's a cumulative endeavor.

Everyone adds their brick to a big structure, as it were.

I think the lesson there is scientists are human like everybody else.

But at the end of the day, we serve a higher goal.

No, no.

At the end of the day, either I'm right or Sir Martin is wrong, or Sir Martin is right and I'm wrong or we're both wrong.

And we both know that going into the conversation.

And for so much dialogue in the world, there's conflict to the point of bloodshed because opposite sides think they have the absolute truth.

Yes, but that's partly because science deals with the external world, whereas ethics and morality and politics are things where...

This one is from Facebook too, Tavis C.

Alley.

How do you think future generations will judge our actions regarding climate change?

Well, at the moment, I think they'll have a lot to blame us for because we realize that we've inherited a huge amount from earlier centuries, not just cathedrals and all that, but all our infrastructure from the last century or two.

And the main concern is that when we have far more benefits than any previous generation, if we leave a depleted world for the future, that will be a terrible legacy, and that's a serious threat if, in fact, we don't address these questions soon.

It's an interesting point because in the United States, one of the great legacies of the country were all the mega projects from the Work Project Administration, WPA, period.

The Hoover Dam, aqueducts, roads.

There was just a huge movement to build an infrastructure for the country.

We only recently, here in New York City, we only recently twinned our water pipes from the reservoirs up in the mountains.

And we would say, oh, why are they breaking them?

They were made 100 years ago!

They're 100 years old!

Oh my gosh!

Yes, that's right.

And I think more generally, even though our cosmic horizons in time are so much larger, our planning horizons got too short.

We don't plan ahead even 20 or 30 years.

So again, this is on climate.

This is from Tim Shaw through Patreon.

What kind of climate?

Patreon, those are the people who actually pay.

They are.

OK.

What kind of climate change influence disaster will need to happen before the majority of the world takes serious action on climate change?

I'm optimistic that the human race possesses everything we need to find climate change effectively, but I'm pessimistic when I see the current trend, especially in politics.

Yes, well, I'm pessimistic too.

And I think the problem is that politicians think parochially in short term, whereas climate change has to be thought in terms of benefiting people in the long term and helping people in remote parts of the world.

My personal view is that the only effective thing is not to have carbon taxes and things, but to accelerate research and development into all kinds of clean energy.

That's a win-win situation because the countries that develop it will have a huge market and countries like India, which need more power, will then be able to afford to leapfrog to clean energy and not build coal-fired power stations.

So I think to promote R&D in energy and things like batteries and storage and all that on a level closer to the level of research in defence and in health is the prime thing we should do.

Imagine if the US spent all the money they spend on defence and R&D for clean energy.

Wouldn't that be great?

Isn't that like billions of dollars?

It's trillions.

Trillions.

That's more than billions.

Trillions is more than billions, sir.

That would be great, wouldn't it?

So, there's so many questions about space travel.

Everybody wants to get out of here.

Bring it on.

So, Gabby Matei, through Google+, in the near future, will space travel be possible for everybody?

Well, not for everybody, but for a lot.

But it's interesting.

I'm old enough to remember the Apollo program.

And at that time, I thought that 10 years afterwards, there'd be footprints on Mars.

But of course, there weren't because the US government has spent 4% of its federal budget on the Apollo program and there was no motive, which was done for superpower rivalry reasons.

Of course, we know what's happening now.

My personal view is if I was an American, I wouldn't support NASA spending any money on manned spaceflight.

That's because I think it should be left to these private companies.

Women.

It should be left to the private companies, like SpaceX and Blue Origin.

And that's because they can take risks.

The trouble with...

Elon Musk blurted his book.

Yep.

But the trouble is that NASA is very risk averse.

I mean, this shuttle failed twice in 135 launches.

Each was a national trauma.

Whereas adventurers and test pilots are prepared to take higher risks than that.

So I think the future lies in cut-price, high-risk ventures, bankrolled by these private companies.

And I hope very much that there will be a community of people like that living on Mars by the end of the century.

But I disagree with Musk and with my late colleague Stephen Hawking in that I don't think mass emigration is ever going to happen, because nowhere in the solar system is as clement as the top of Everest or the South Pole.

And it's a dangerous illusion to think we can solve the Earth's problems by going to Mars.

Dealing with climate change is hard, but it's a doddle compared to terraforming Mars.

I agree 100% and I'm publicly…

I don't want to say that I'm opposed to mass migration, but I just…

I don't mind if we all want to live on Mars, but I don't think people fully understand what that involves.

It seems like if you mess up your bedroom, then you move house.

So watch what happens.

So if we're really going to ship a billion people to Mars because something bad happened on Earth, because a lot of the argument, especially put forth by your eminent colleague, the late Stephen Hawking, the argument was…

And you can see the argument.

It makes a good headline.

You want to be a multi-planet species in case something really bad happens on one of the planets so your species can still propagate.

I get that.

But if you want to ship a billion people to Mars to protect humans, terraform it in advance to do so, it seems to me…

Whatever it takes to terraform Mars…

The resources…

You could terraform Earth back into Earth if you messed up all the resources.

But I think there will be these crazy pioneers on Mars.

And rather than terraforming the planet, they will modify themselves to adapt.

Because by the end of the century, we'll have genetic modification techniques and cyborg techniques.

So my view is that a post-human era will be pioneered by these people on Mars because they've got every incentive to adapt themselves to a hostile environment.

They're away from all the regulators.

And so they will evolve into a different species very quickly.

They're away from the biological regulators.

So they can actually introduce biological variation suitable for the Martian environment.

Yes, and maybe at that stage they can download their brains into electronic form, et cetera.

And that means that the species will have its descendants who will be generated by those people on Mars.

Oh man, if I downloaded my brain, it's so glitchy and anxiety-ridden.

I don't know if we want to replicate that.

No, that's a separate question.

We'll deal with that in another show, Maeve.

Whether it will still be you.

I don't know.

Maybe me, but just in silver body form.

Because all future people are dressed in silver.

That's what I'm saying.

Oh my God.

Another one.

What else you got?

This one is from Chris Ryu.

Fast forward a decade or a few decades and imagine this permanent Mars colony that we were talking about.

Assuming that NASA were the ones responsible, what changes do you think that would mean to the role of NASA?

Well, I think if NASA were responsible, it would have to go on.

But my line, which I discuss in my book on the future, is that the role of NASA would be just that of an airport rather than airline, as it were.

In that they may provide some basic facilities, but it will be the private companies that provide the spacecraft and take the people prepared to accept high risks.

So I think NASA will be phased out, and it will be public money not spent and private money spent.

As you may know, the FAA has recent legislation.

I don't know if it's been fully voted on, but there's not much resistance to it, where they will now be the shepherds of the future space launch sites, space ports.

And you can propose to have a space port, and they would be responsible for checking the safety of it, the safety of the downrange launches, the safety of craft that were launched.

So this is a first step in precisely what you're saying.

They shouldn't be too stringent, because they should remember that some people are prepared to go on one-way tickets, and people like Steve Fossett, and these guys who go hang gliding in Assymete, they take very high risks, and they ought to allow people like that to risk their own lives, and we cheer them on.

We interviewed someone who wanted to go on these one-way trips to Mars.

We had him on our show, and I said, what does your wife think about this?

She said, oh, she encouraged him.

Have you thought this through?

She's doing a GoFundMe, send him to Mars, come on.

Well, Elon Musk said he wants to die on Mars but not on impact.

Oh, good, that's good.

Well, I think that might...

Okay, time for one more quick question.

I think it might.

We have answered Mark Fesco's question from Facebook, where he asks, will companies such as SpaceX eventually make NASA obsolete?

Yeah, but let me give a counterargument there.

To do something first that's expensive and dangerous doesn't really come with a business model.

That's a very short venture capitalist meeting.

Elon, what are you doing?

I'm going to put humans on Mars.

How much will it cost?

I don't know, a trillion dollars.

Is it dangerous?

Yes.

Will people die?

Probably.

What's the return on investment?

Nothing.

So how do you do that first?

My research of the history of this exercise says that governments do this first.

Then they find the trade wins and the patents are granted.

Then private enterprise comes up behind that.

But I'm saying you would never have that grandiose goal of sending a million people.

You would just have a few pioneers who would go.

The point is that space is not like climate change where governments have to coordinate.

It doesn't have to be everyone agreeing.

It can be just one corporation doing it.

And one individual.

And therefore there's much greater freedom.

Much greater freedom.

Of creativity and decision.

Yes, and a greater capacity for accepting risks.

Good point.

Because the FAA doesn't want people dying.

And so that might actually be a delaying force compared to what you're describing.

So he wants the Wild West base exploration.

All the bad kids who smoke around the back of the school.

The risk takers.

The bad boys.

All right.

We got to take our next break.

And when we come back, more cosmic queries on the future of humanity with Sir Martin Rees and Maeve Higgins when we return.

We're back for our final segment, Cosmic Queries, The Future of Humanity, featuring the recent book by my friend and colleague, Sir Martin Rees, On the Future, Prospects for Humanity.

So, let me just lead off.

She's got her list of questions from our people, but I'm just curious, is there, how important will science, I think I know the answer to this, but I want to hear it from you.

How important will science literacy be going forward as science becomes so much more centered in decisions we have to make about our own fate?

Well, I think it's crucially important that everyone should have a feel for science.

That's why things like your outreach are so important because so many of the decisions we have to take are on energy, health, environments, and you need to have some feel for science, not to be bamboozled by bad statistics and things like that.

And so it's very important that everyone should have a feel for science.

But also, it's part of our culture, isn't it?

And everyone wants to know about our place in the universe and of course nothing fascinates kids more than dinosaurs, even though they're completely irrelevant.

So I was like, no, but it's important for educators.

They tend to think you have to make things relevant.

I win that argument.

I said, one of our asteroids took out your dinosaurs.

Yeah, yeah.

So we're done here.

So dinosaurs and space are what fascinate kids.

All of these eight-year-old children just weeping listening to the show.

So what else you got?

This is our last segment, so make them good.

OK, are you ready?

This is from Jake A.

Wynn.

He got onto us through Instagram and he asks, what's the next E equals MC squared?

Meaning, what do you anticipate will next shake the foundations of physics on that level of wow factor?

Oh, nice.

Right.

Well, of course, the biggest wow is now coming not from physics, but from biology, understanding the brain and the complications.

And I like to say physics is the easy subject.

Stars and atoms are far easier to understand than even an insect.

So the big challenge is to understand life and the brain.

But if you want to ask about physics, then the next big step is to unify the very large and the very small, to unify what Einstein did with the physics of atoms in the micro world, what's called quantum theory.

And until we have that, we won't understand empty space in the bedrock sense.

And we astronomers worry about something called dark energy, which is a force latent in empty space.

I think my ex-boyfriend had that dark energy.

But that's a big challenge for physics.

Is there some state of the universe that is on the brink of collapse and we don't know it?

Well, if you don't know it, I can't answer your question.

No, we could be walking along the edge of some cliff and the cliff is not visible to us until you step there and then everything collapses.

Well, that's certainly possible.

But another point which I make in my book on the future is that there may be some important aspects of reality which our brains just can't cope with.

I mean, a monkey can't understand quantum theory.

And likewise, there may be deep issues which are just beyond our brains and have to await these post-humans.

And they may answer that sort of question.

Do you mean like...

That's after they make us their pets.

We're going to be their pets.

They're not all that bad.

No, we'll just be rescues.

But do you mean like we can't understand what's happening in front of our eyes?

Like something like, remember when some people saw ships for the first time, they just didn't see them because they didn't know what they were.

That's what you mean.

Yes.

Yikes.

And because that's relevant to aliens and SETI because they may be so different from us that we wouldn't recognise their manifestations.

Oh my God.

OK, so this is about the Hadron Collider.

Isn't there a part of the large Hadron Collider that emits a magnetic field stronger than that of Earth?

Why can't we somehow place something similar on our future spaceships?

That's from Ramon Hamilton.

Oh, to protect us from solar radiation, correct?

I guess, yes.

Is that...?

Well, maybe we can.

People talk about that.

But you need a so-called superconductor or you need power to maintain the magnetic field.

But certainly radiation damage is an important constraint on manned spaceflight.

And that's why Dennis Tito had the idea of sending people around Mars and back 500 days.

And his favorite crew are a middle-aged couple to be cooped up for 500 days happily and to be old enough not to care about a radiation dose.

To become sterile at the end.

And also a middle-aged couple, they're happy to sit in silence together for long periods of time.

That's right.

That's right.

It's perfect.

Yeah.

So don't volunteer yet.

So yeah, so that's an interesting fact.

And the point Sir Martin was making was that you, you know, every pound, every kilogram matters that you're sending into space.

And so if you're going to have a system that creates a magnetic field around your ship, there's the weight of that versus the weight of what might just simply be shielding.

Yes, a whole lot of lead.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

That was a good question.

Yeah, what else?

What else do you have?

Given, this is from Matthew Belitho, given that a particle's interaction with the Higgs field is what gives its mass, is it conceivable that in future, when we understand this interaction more thoroughly, we could devise a machine by which we could completely nullify a spaceship and its contents interaction with the Higgs field, rendering it completely massless and therefore capable of light speed and beyond?

Whoa!

Whoa!

Just say yes.

Just say yes.

I think you don't know.

I mean, I should say, we can't conceive of what might happen in the far future.

That's a very kind answer.

That needs a bigger brain than we do.

You have to watch out, of course, because for almost everything we've discussed, there's that off-ramp of the weaponization of that new technology.

And so you can imagine if you had control over the mass of something and that became weaponized.

Well, I mean, one of the themes of my book on the future is that the stakes are getting high because every new invention has benefits and a downside, but they're getting bigger.

So a knife can cut your food or kill someone, but a knife can't kill a thousand people.

A thousand people will kill you before your knife kills a thousand people.

But other kinds of weaponry, that equation is different.

Yep, that's right.

And there's a risk of error as well as design.

Right, right.

This one is about communicating, I think, with with aliens.

Timothy Cullnan.

Has anybody thought to watch for coded patterns in starlight tips that could be used as communication?

As if a very advanced civilization intentionally put large objects into orbit around a local star to create such an obvious message that distant intelligent observers would recognize it as a message.

I could imagine our civilization attempting something like that in the future if we could.

Well, of course, there was this object called Tabby's Star where people thought something might be happening.

But it's primitive communication, rather like smoke signals.

But my view is that if SETI searches detect anything, SETI, Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, if they detect something, it won't be anything like our civilization.

It'll be some sort of machine created by some long dead civilization and it might be sending out some sort of transmission.

But it's unlikely that it's a message we could decode.

So I'm pessimistic about being able to decode a message.

Because if they're in any way smarter than us, their simplest thoughts will transcend our deepest thoughts.

They might.

They might not be interested in sending a message, but we might find evidence for something which is manifestly artificial.

And that in itself would be, of course, a big breakthrough.

And of course, you were around for the discovery of the pulsar, correct?

Yeah, I was a student then, yes.

You were a student at University of Cambridge.

And so Anthony Hewish, I think it was.

Hewish and Bell.

And Jocelyn Bell.

So they find a star that is blinking at us in radio waves.

We don't have that word yet.

Excuse me.

It's not invented yet.

Right, a star is.

So you were just like, look at the blinking star.

Look at the blinking, and it's keeping perfect time.

And the famous LGM, I think, was written on the page.

Yep, that's right.

Little green men, right?

It was so different from anything that was known before.

Right, right, and that would be, that's an example of a signal.

So our history in our field says, if you see a signal that is regular and perfect, is it just something we've yet to discover in nature that is regular and perfect, or is it intelligent aliens sending us a signal?

And the history of this is that it's a new phenomenon in nature.

It's not aliens, unfortunately.

Because we all want to meet the aliens.

Wasn't it kind of, you know when the humans sent out the Golden Record, they had instructions on the side of how to...

How to decode it.

Yeah.

What do you think of that?

In fact, you were also blurred by Ann Drion, who was the creative director of the record, of the Golden Record on the side of Voyager.

So I'd be curious what your thoughts are.

This is our attempt, people may remember, on the side of, just Google it, the Golden Record, there are pictograms on the side that, of course it's not written in English, but there are pictograms that are an attempt to share our science with them.

Yes.

Well, I mean, I think it was a good exercise to do that.

And I think there's a plan for Ann to do a similar competition for schools, to find something similar, to design something.

And that's a great idea.

But I think the chance of any alien is picking that up and decoding it is far smaller than them detecting sort of radio and TV transmissions from the Earth.

That are already leaking from Earth.

They're already leaking, yeah.

And incidentally, there's some people...

Because that's emitting a whole bubble.

So wherever you are in any direction, you're going to receive this bubble, whereas otherwise, you've got to be right in line with the...

With that little tiny little voyager.

And some people say we should beam some signal and other people say we shouldn't do that.

We should hide.

And I can't take that seriously because I think if they're more advanced than us, they probably know all about us.

They're probably watching us already.

Do you think they're not bothering with us?

Yeah.

Wait, Martin, you wouldn't give your email address to a stranger who is human in the street, much less the return address of Earth to aliens in the universe.

We saw those movies.

We know what they'll do.

No, but I think they would know about us already.

I think the directed signal...

So we're already a zoo for them.

They already know all about us.

They're watching us with interest.

A planet of interest.

Keep going.

All right.

So this is from Instagram, the C word as in SEA.

This is from Instagram.

Is it more practical to research interdimensional travel rather than faster than light travel?

More practical.

Well, I think neither is really practical.

What's more fun, do you think?

But going...

Sending things at the speed of light, of course, is OK if it's information.

And of course, one of the ways of sending information across the galaxy would be to send a code for DNA or something like that, at the speed of light.

But of course...

Yes.

So I think those are probably beyond the science fiction fringe, although one should never say that because we've no idea what will be done in the far future.

We've got about two minutes left.

I want to make sure we have...

I want to hear Martin's deepest sort of summative reflections on where we are, where we've been, where we're headed.

Martin, what can you do for us here?

Well, in my book On the Future, I emphasize that this century is very special because depending on what actions we take now, we can either leave a depleted world with mass extinctions and an unappealing climate, or we can trigger the transition to a space-faring civilization where human evolution will be succeeded by a post-human era which could spread beyond the solar system, indeed through the entire galaxy.

So the stakes are very high, and the concerns are not just about ourselves, our children and grandchildren, but about the long-term future of humanity and of post-human life.

But when you think of post-human, why can't we just think of better humans?

So we have access to the genome, now I get rid of disease, I make you live twice as long, I maybe reduce the chemical inefficiencies in your body so you don't have to eat as much.

How about that?

Or how about humans that are already managing to do that, like indigenous communities who live in harmony with the earth?

Well, there's one possibility.

Some people might like that.

I wouldn't.

No, I'm not your iPhone.

Of course, some people might prefer to download themselves into something electronic and be frozen until that era is reached.

You'd rather do that than just live in a city like Petra that's made out of sandstone where you get to have running water and beautiful life.

Well, I think many people would.

And I think they may not want to be more intelligent because there was this attempt by Shockley to set up this sperm bank for Nobel Prize winners.

He co-invented the transistor for Bell Telephone Labs.

But then he went into interracial thoughts.

He said, let's breed another race.

This is very eugenics.

But he's gratifying that there was no demand.

But the funny thing, Ray Kurzweil, he's a guy who thinks that machines will take over and he wants to be frozen, his blood replaced by liquid nitrogen, until that era.

And then they bring him back and then he's in the mix.

They bring him back and I don't go along with this.

I've told people who advocate this, I want to end my life in an English churchyard, not a Californian refrigerator.

I love English people.

I think we should end it on that note, I'm pretty sure.

So, Sir Martin, it's a delight always to see you and to see what conference is and when you present and I always like tracking your books.

So thanks for coming to New York for this.

Well, and thanks Neil and congratulations on all you're doing to spread enlightenment.

Yeah, I can't wait till other people are doing it and then I just go to the Bahamas.

Martin Rees' latest book, On the Future, Prospects for Humanity, and it's a fast read, but an important read because the future of humanity lies in the Brinks.

And Maeve, good to have you.

We're busy.

That's why I haven't seen you.

We wrote a book, Maeve in America.

I love your observations of American culture.

It's simultaneously embarrassing and hilarious.

Thanks for the chat.

You've been watching, possibly most likely listening, to this edition of StarTalk, The Future of Humanity with my featured guest, Sir Martin Rees.

I've been your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and as always, I bid you to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron