About This Episode

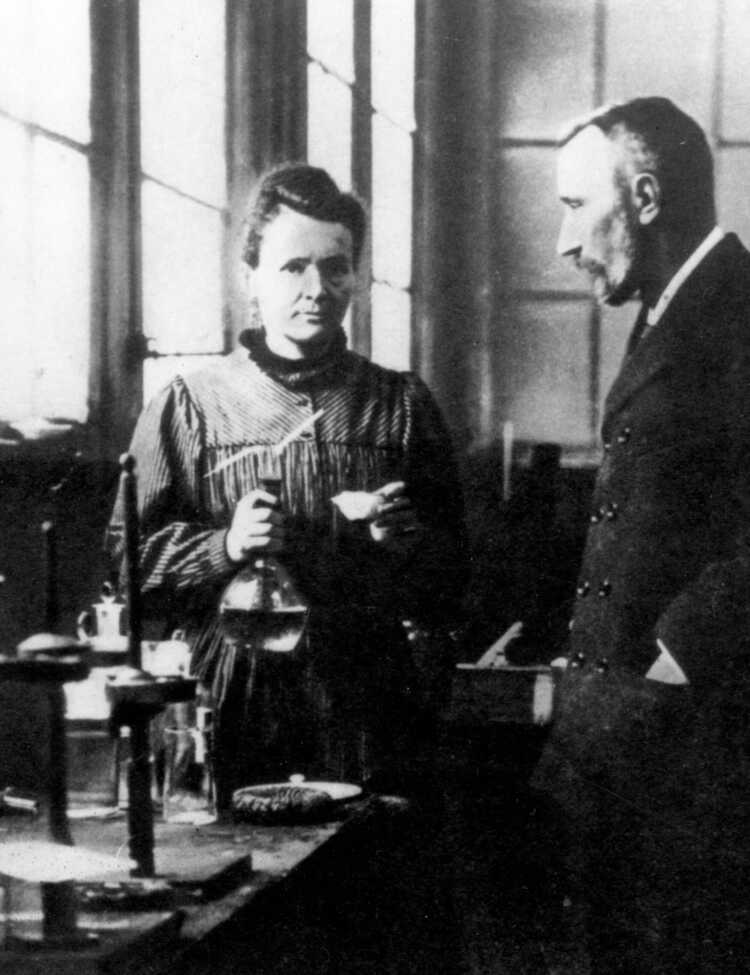

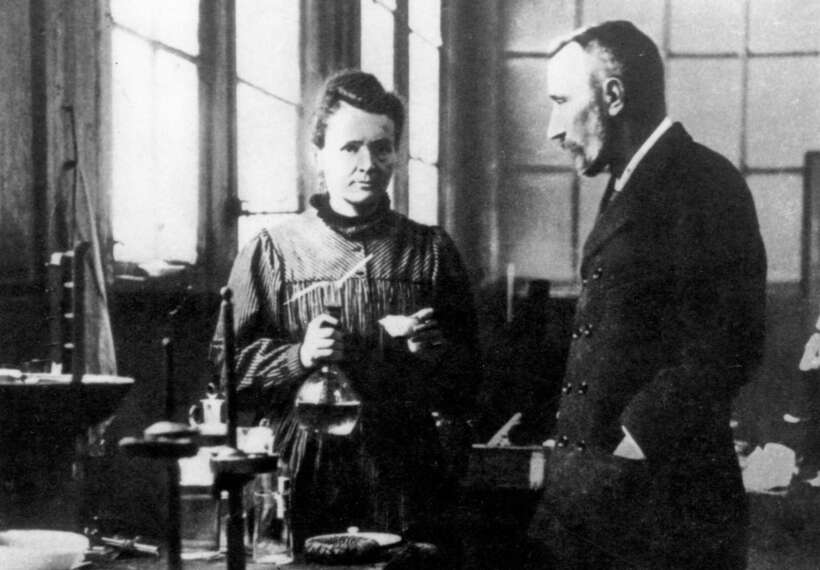

How did Marie Curie’s discoveries in radioactivity change our understanding of the natural world? Neil deGrasse Tyson and comedian Chuck Nice sit down with science writer Dava Sobel, author of a new book on Curie, to explore the enduring impact of her work on radioactivity.

Discover how Curie’s meticulous research led to the isolation of radium and polonium—elements that unlocked the mysteries of radioactivity and laid the foundation for modern physics and chemistry. Learn how her insights paved the way for radioactive dating, which determined the Earth’s age, and her revolutionary contributions to medical science, including the use of radium to treat cancer and the development of mobile X-ray units during World War I.

We dive into the science behind her two Nobel Prizes—one in physics and one in chemistry—and her perseverance in refining tiny quantities of radioactive material from tons of ore. We also discuss the risks she and her collaborators faced as the dangers of radiation exposure became clear, as well as the scientific advances inspired by her work, including the creation of artificial radioelements for medical applications.

From her early experiments to her lab notes—still radioactive today—Curie’s story is one of unrelenting curiosity and dedication. Join us for a deep dive into the science that defined her career and the discoveries that continue to shape our understanding of the universe.

Thanks to our Patrons Steven Dominie, MICHEAL EMANUELSON, Troy L Gilbert, Johnny Mac, Micheal Benvenuto, Keti Khukhunashvili, David Cashion, Lord Bane, Pat Dolloff, timothy jones, Amir Torabi, Catherine B, Lewis Z, Andrew Troia, Samurai_wolf_6, mike johnson, The Analytical Btch, Mark Petry, Randy Harbour, Garrett Gilbeau, Christopher Manning, Sulla, Jeremy Wong, P Soni, that one guy Kamaron, and Bisexualstardust for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTSo Chuck, I love having guests come back.

Why, is it so rare?

No, no.

It so rarely happens.

They run away and never return.

No, no, no, it’s Dava Sobel is a fixture on the landscape of science writing, and has gone places that others haven’t, or ever even thought to go.

Well, she took us there, so it was just tremendous.

Just tremendous, especially since she was our first ever guest.

Wow.

Season one, episode one of StarTalk, a bajillion years ago.

Coming up, Dava Sobel.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk, Neil deGrasse Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist.

Got Chuck Nice with me, Chuckie baby.

Hey, Neil.

Yeah, so guess who we have as a guest today?

A very special guest?

Let me tell you how special.

Beyond special.

Beyond special.

Okay.

Let me tell you how beyond special this person is right here.

See her right here?

Can we see all the camera?

Okay.

There we go.

Dava, welcome back to StarTalk.

This person sitting to my left, our record show was our very first guest, season one, episode one of StarTalk.

Wow.

Dava Sobel, we’re unworthy.

We’re not worthy.

You were there at the beginning.

Oh my gosh.

We call that telescopes that rocked our world.

And yeah.

And back then it was only audio.

So we didn’t, no, that’s all we had.

Okay.

Well, here we are.

That’s like prehistory.

So you’re a science writer, but you cut your teeth as a journalist for, was it Gannett Papers in Long Island?

What was it?

Oh, it was in upstate New York when I worked for them.

And-

Them is Gannett, and Gannett is everywhere.

Was right.

It was the Binghamton Evening and Sunday Press.

Binghamton.

Wow.

Okay.

Binghamton, the town in New York, upstate New York.

And there was IBM there.

I was briefly, very briefly a technical writer for IBM.

Okay.

So you had some science chops early.

Yeah.

Okay.

I went to your high school, too.

Graduate of the Bronx High School of Science.

Whoa.

Uh-oh.

That’s Sirius Bonifides, as they say.

Okay, so you already had a science baptism, becoming a journalist.

Yeah, yeah.

Wow.

Yeah.

And I didn’t even know it was called science writing.

And I wish somebody had told me about it sooner, because it would have made my journey a lot more direct.

I was just a lost soul for a long time.

Oh.

But I’m happy now.

You’ve been found.

Saved by science.

Saved by science.

Saved by science.

I think most people came to know you through your, I don’t know if it was your first book, but the first book that did really, really well, of course, and that was The Chronometer Story.

Longitude.

Longitude, yes.

The story, the subtitle.

You know, if you read the title in the subtitle of this book, you say, I ain’t buying that.

Who’s going to be caring?

Exactly.

I didn’t think anybody would buy it.

Yeah.

Give me the subtitle.

What was it?

The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time.

Oh, no.

I’m buying that book.

Wait, wait, wait.

How are you kidding me?

That’s like a scientific telenovela.

Well, I know, but it’s titled Longitude.

Longitude.

That’s what I’m saying.

You might have lost me there.

That’s what I’m saying.

And people still ask me, what’s it about, really?

It’s hilarious.

And you wouldn’t utter the man’s name because no one heard of him, but Harrison?

John Harrison.

John Harrison, who invented the first Seaworthy Chronometer, which is a runaway mega bestseller, okay?

And another one, Galileo’s daughter, yes.

Whose name was?

Well, she was Virginia, but then she became Suor Maria Celeste.

Celeste.

When she, Celeste.

Celeste, that’s the sky right there.

Okay, okay.

And then there was the glass ceiling.

Actually, it was called the glass universe.

The glass universe.

But you know, even my editor called it the glass ceiling all the time.

Oh, yeah, so that one was, that was a good one.

Let me just declare that my people are pretty well informed about that part of our own history in astronomy.

There’s a whole community of women at the Harvard College Observatory, but we knew that this story was not told beyond our own retelling among ourselves.

And this was an important exposition of the role that women played in early science and in particularly early astronomy.

Yeah, the glass universe.

And what was the subtitle on that one?

How the latest of the Harvard Observatory took the measure of the stars.

Oh, wow.

You make great titles.

Thank you.

So, we’ve got you here and now, because you have yet another book.

Yep.

Just setting the record straight.

Okay.

Just let’s do it.

Marie Curie.

Oh, okay.

Everyone don’t go.

Wait, wait, wait.

Okay, I’m not gonna read the subtitle, because I want you to compliment her on the yet another subtitle.

Okay, go ahead.

Here it goes.

Give it to us.

Marie Curie.

How the glow of radium lit a path for women in science.

Oh, so you’re just showing off now.

You’re just showing off.

The glow of radium.

The glow of radium, that’s pretty wild.

Yeah, and I see what you did there, too, because didn’t she discover radium?

She did.

She discovered radium, and was it polonium?

We’ll get the whole thing.

Oh, I’m sorry, I’m just trying to remember my…

Oh, you remember polonium.

Oh, I got thoughts about polonium.

That was another one that she discovered.

Yeah, that was actually the first one.

Yeah, and so we can’t name them all curium.

She didn’t name any of them curium.

That came later.

Yeah, and the first radioactive element was radium.

Well, uranium was the first one.

Oh, sure, sure, but what she worked with…

What she discovered, the first one was polonium.

So how many elements did she discover?

Two, polonium and radium.

All right, and later on we would name an element in her honor curium.

Gotcha.

So how did Marie Curie land in your lap?

I had a, almost a religious experience in the course of writing The Glass Universe, because the story was all about women, and over and over I kept finding myself surprised by what they had done.

And I finally had to admit that I had embarrassingly loved the low expectations of them.

And even though I’m a woman, my mother was a scientist, I had all these reasons.

True.

I had all of these reasons to be more respectful.

I had just picked up the negative attitudes about women that were in the air in the 19th.

You had a man bias.

I definitely did.

And so it stunned me.

And then I had several astronomers fact-check that book.

And one of them was Alyssa Goodman at Harvard.

And she apologized right away.

She said, I’m not really focusing on your descriptions of astrophysics because I’m so gobsmacked by these women.

Here I am at Harvard.

I know all their names, but I always thought it was something cute or quaint.

I never realized they were doing science.

So this kind of misogyny, these low opinions of women in science are very widespread, very insidious.

And that made me want to tell more stories about women in science.

So my editor immediately suggested Marie Curie.

And I said, no, because everybody knows about her and I don’t have anything new to say about her.

So I wouldn’t want to just regurgitate facts.

But then I was asked to review a book called Women and Their Element.

And it was all about women chemists, more than 30 of them.

And in reading the profiles of these women, six or seven of them had a direct connection to Marie Curie.

And that was interesting.

It was like a little network.

So I got in touch with the Curie Museum in Paris and they had records.

There were about 45 women who worked for her.

So this was something I knew that nobody knew about Madame Curie.

She was like the Harpo Studios of Science before Oprah.

So they gave you access to these records?

Not just then.

They actually had a book published, little sketches of the women in alphabetical order with some biographical details and references to the papers they had written.

This is the stable of other women working in Marie Curie’s laboratory.

Right.

45 women.

45.

That’s phenomenal.

How does it even get to that number?

Because of the position she was in.

So she and her husband shared a Nobel Prize in 1903 and then he was killed in an accident.

And she took over the laboratory and his teaching position.

By the way, his name is Curie.

Yes.

Her name was Sklodowska.

Sklodowska, yes, so she’s Polish.

Oh, though we think of her as…

Think of her as French.

As French, right.

Because of Madame Curie, of course.

She had to go to Paris to go to university.

Why?

Because in Warsaw, where she was born, women were not allowed to attend university.

Wow.

Yeah, yeah.

And we’re not talking about the 1600s here.

We’re talking about the late 1800s, yeah, yeah.

First woman ever to teach at the University of Paris.

So now she is really a phenomenon and a magnet for women scientists.

Oh, of course.

Oh, cool, yeah.

All the other women in Poland who weren’t allowed to go to school.

Some of those.

They were like, so we’re headed to Paris to study under Marie.

Norway.

I didn’t want to undervalue the value of her visibility.

Yes.

In the ambitions of others.

Oh, my gosh.

Whereas I think women have always been interested in science, found ways to participate in science.

She was the first one who really was in charge of a laboratory and a professorship.

Okay, so today, most people, when asked, name a famous female scientist, the only scientist they can name is Marie Curie.

That is the sad truth, yes.

Okay, so you’re not helping that matter, because you just published a book on Marie Curie.

Guilty as charged.

So maybe the rest of these women, are there stories that can be highlighted among them?

Yes.

Oh, well.

Yes.

Is that also part of the book?

That is what the book is about.

Oh.

It’s about all these other women.

It’s about the legacy.

There you go.

Yeah.

And it was during her lifetime.

They came because of her, and then she collaborated with them, published with them.

She taught a course, so she was inspiring students in that class.

Even before she taught at the university, she had taught at a teacher training school for women, and she taught physics.

Wow.

That was her field.

So she shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Pierre.

But then…

In 1903.

In 1903.

But then in 1911, they awarded her, the Nobel Committee awarded her the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Wow.

And she alone.

So she didn’t share it with anyone.

Yet most Nobel Prizes are shared.

Thank goodness that she did that.

Because, I mean, I hate to be cynical, but if you share a Nobel Prize with a husband, you also share his name.

And you have his name.

People are going to automatically fall into the bias of, well, clearly she was his assistant.

He did the work.

That happened.

Even though she won a second Nobel Prize.

Even though she won.

It’s really rough for women.

Let me tell you.

Man, that’s tough.

That’s why I was glad she won a second one, so to erase any stigma that might have been attached.

Second one outright.

Yeah, this is all her.

No, it still got said that she was just his assistant.

Oh, man.

And the reason they took on that work, it was her dissertation project, when it got really interesting, Pierre quit what he was doing to work with her.

Yeah, just like a man, okay?

I didn’t say that.

No, I’m saying it.

But she had a good friend, a British physicist, Hertha Ayrton, who was also married to a physicist, and they intentionally worked on different things, just so that no one could say that Hertha was her husband’s assistant.

The assistant, wow.

So, highlight some of the science that came out of her lab and her brilliance.

Well, radioactivity, which was her word, was a new phenomenon, and that’s why she got interested in it.

So, x-rays were discovered in 1895, and that was a huge interest.

A thousand papers on x-rays got published.

That got the first Nobel Prize in Physics.

Wilhelm Röntgen in 1900.

Okay.

The discovery of x-rays.

What an unfortunate name, but.

What, Wilhelm?

Wilhelm Röntgen.

Röntgen.

In fact, we’re the only ones who call them x-rays.

Everybody else calls them Röntgen veins.

Röntgen veins, right?

What?

You didn’t know that?

No, I did not.

I’m sorry, we got your Röntgens back.

And it appears that your wrist is fractured.

That doesn’t work for me, you know?

We got your x-rays, I don’t know, it just sounds great.

What did Wilhelm call them?

He called them x-rays.

We’re good here.

So the very next year, Becquerel in France, Henri Becquerel.

Henri Becquerel.

That’s a good name.

Multicultural we are.

That’s a good one.

So he was curious about x-rays and wanted to see if maybe it was an effect of fluorescence or phosphorescence, but he noticed, and he was experimenting with a uranium crystal, and something else was coming out of the uranium that was not x-rays.

And he got very interested in that.

He called them uranic rays.

And everybody else was so interested in x-rays that nobody picked up on the uranic rays.

So Madame Curie, now looking for a thesis topic, thought that’ll be good for me because it’s interesting.

And her husband was an inventor of instruments and…

Scientific instruments?

Scientific instruments.

And there was a way to measure the strength of these uranic rays that some of his instruments could pick up.

So it just seemed to be perfect for her.

And soon she…

So she started testing all the elements to see if anything else emitted these uranic rays.

And she found out that thorium also did.

Named for?

You know, the god of the Bifrost.

Thor.

Thor.

Yeah, it was a huge fun history of culture and mythology and people embedded in the periodic table.

So thorium…

And then she was testing some uranium ore and got a reading that was far higher than either uranium or thorium.

And so she concluded that there was an unknown element and as yet undiscovered element that she could discover on the basis of its radioactivity.

That was her word.

Did you say that earlier, that whatever, this other ingredient is found with uranium?

With uranium, yes.

With uranium, yeah.

Yeah.

So that’s pretty wild.

She inferred its existence.

Right.

Exactly.

Because pure uranium wouldn’t do that.

She’d already tested that.

But she knew what its strength was.

And this was much, much higher.

So first she re-tested everything, make sure she didn’t make a mistake.

And then she said, there has to be a new element.

Wow.

And this is part of the excitement of this period, that the periodic table was a work in progress.

It still is, but there are no gaps, is the point.

There are no more gaps.

It’s still increasing at the high end, making bigger fatter elements.

And there’s a hypothesized place, because all these elements are highly unstable, but there’s an hypothesized place based on equations of atomic nuclei and their stability.

That is called, we think there’s an island of stability, just a few more elements down.

If you make those elements, then they’re permanent and they won’t decay, like all these other elements do.

And so there’s a hunt now for the island of stability.

So we’re still working the table, but everything, you were talking about filling in gaps.

Filling in the gaps.

That were there.

Right.

There were a lot of gaps.

And in the course of breaking down this ore to isolate the new element, she realized there were two different ones.

And the first one they identified was polonium, which they named for Poland.

Right.

And then…

Because of her.

Because of her.

Yes.

Yeah.

Because she was very fiercely Polish.

Yeah.

Yeah.

And had originally intended to get educated in Paris and then go back to Poland and teach and uplift her country people.

Right.

But she fell in love.

A colleague of hers thought that he might be helpful to her and her work.

And they fell in love.

Neither of them expected that, but they did.

And what was her line?

I’m…

It was, she wrote to one of her family members that it’s a grief to me.

It’s a grief to me.

To remain forever.

To remain forever in Paris.

But I am deeply in love.

Wow.

Today, there would just be an emoji.

We lost all ability to communicate.

I want to say, she could really write.

Her scientific papers are so clear.

They are a marvel of clarity.

By the way, my wife would leave me for plane tickets to Paris.

I would have been in the universe, but no, there’s some hard work to make this happen.

So tell me, no one understands at the time that radioactivity will harm healthy tissue.

So what, give me some backstory on that.

Well, you’d think they would have figured it out right away because they had burns on their hands.

And if they carried a vial of the stuff in a pocket, they got a burn on their body.

So this immediately drew the attention of medical doctors who saw this material as a treatment for cancer.

And for several decades, radium was the cure for cancer.

For tumors, you would attack the cells of a tumor.

Exactly.

And it would destroy.

And radiate into the cells of the tumor.

Exactly.

Wow.

How would they do, would they drop radium into the tumor itself or what would they do?

It changed over time.

So the first two patients, two women with breast cancer, were actually brought into the Curie’s Laboratory.

And had their…

So somebody had to have that thought to even consider this.

Right.

There was harm associated with it, obviously, but it was doing so much good.

And it was so interesting.

When did they find out that radioactivity also causes cancer?

Well, I think the real big moment was in the 1920s with the dial painters.

So these were young women painting the numbers on glow-in-the-dark watches and instruments using paint that actually contained radium.

And they were told to put the paintbrush between their lips to get a nice point, and it destroyed their jaws and they died.

Their teeth fell out, it was horrible.

That’s terrible.

And of course, Madame Curie never advocated paint full of radium, that was not what she was…

Yeah, but think about it, think of how amazing it is that there’s something that’s glowing all by itself.

That must have been just stupefying.

Yeah, and that appealed to Marie and Pierre from the beginning, that as they would try to break down this ore and they’d have different dishes of this or that, they didn’t know what it was at first.

And at night, there would be a glow.

But it isn’t really the radium, right?

Even in the paint, the radium shoots out an alpha particle that excites the other ingredients in the paint.

And that’s what’s glowing.

That renders it visible.

Yeah.

This is a pivotal moment in the history of science.

Absolutely.

In physics and chemistry.

Yeah.

Absolutely.

Because it’s not just-

And it’s a moment when physics and chemistry really meet.

Meet and they meet society in a fundamental way.

Would you say that the concept of radioactivity and its value to dating things for their age all began with Marie Curie?

Is that a fair credit to give?

Yes.

She wasn’t doing that work, but other people in her lab were.

Including some of the women.

Okay.

Because if something is radioactive, you have a certain amount of that substance in your sample.

If it’s radioactive, it’s changing identity.

It’s becoming another element, right?

It’s very alchemical, isn’t it?

Ah, look at that.

Look at that.

Which was a big problem at first.

Changing one element into another, is that even possible?

Right.

Because we’d already given up on alchemy.

Exactly.

Right?

If you know the rate at which it’s changing, and you know how much you started with, you’ll know how old the sample is.

Right.

Because how long it’s been there.

Yeah.

And oh my gosh, how useful that is, especially to geologists.

Yeah.

Yes, the age of the earth was determined in the wake of these discoveries.

Cool.

And it was much older than anybody had thought.

Older than 6,000 years.

You think?

You think?

That’s so funny.

Tell me about her second Nobel Prize.

What was she cited for in that?

The one in chemistry.

Specifically for the discoveries of the new elements and her isolation of radium, which she had only recently managed to do.

So these elements existed in such tiny quantities that from a ton of ore, she would get a fraction of a gram.

You know how big, how much a gram weighs?

Um, how big is the cracker?

No, I don’t know.

How much is a gram?

It’s hardly anything.

It’s one thirtieth of one ounce.

One thirtieth of an ounce.

Yes.

Yeah.

See, that is information, as a proud American, I will never need.

Tell me about her daughter.

Oh.

What’s up with that?

She had two daughters, and the older girl was very much like her father.

And Marie always dreamed that she would become a scientist, which she did, and she also won a Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Wow.

Talk about a bloodline right there.

So when was the daughter’s Nobel Prize?

1935.

And what’d she do it for?

She and her husband found a way to create…

Uh-oh, the husband is in there again…

.

another husband.

She repeated the story.

Married the lab partner, worked together.

Wow.

And made these tremendous discoveries and shared the Nobel Prize with him.

Look at that.

You have become your mother.

So what did she discover?

They discovered a way to make artificial radio elements, which had a big advantage over natural radioactive elements because they would decay to something non-radioactive immediately.

So they could make safer tracers.

Wow.

Very important in medicine.

In medicine.

Exactly.

Because you don’t really want to be using radium to treat your cancer.

That’s fascinating.

Yeah, because not all elements are created equal.

Some decay faster than others.

Right.

Yeah, so that their lethality or their harm factor drops exponentially from when you needed it at its peak.

Right.

And so, yeah.

In fact, depending on how long you need the treatment, they just pull one off the shelf that has the right radioactive profile.

Absolutely.

Right.

So she’s creating the ideas and the foundations for whatever medical instruments would later be built in the service of human health.

Some of the people who got the Nobel Prize for those discoveries, basically, she would call them and go, you’re welcome.

That’s how science builds on itself.

Yeah.

Yes.

Yes.

Did you want to talk about the love affair?

So by the time of her second Nobel Prize, her husband’s gone.

He’s deceased.

He was, yes, five years.

Gone.

And from what I understand, there was some highly written about in the media affair between her and a married man.

Do I remembering this correctly?

Yes.

Okay.

And today, I don’t know how important that would be to anybody.

So in the late aughts, okay, early 1910s, that information is received differently.

Now she’s a celebrity, so everyone is gonna care about her sex life, okay, because that’s what we do.

That’s how that goes.

So did this matter to the Nobel Committee?

Were they?

It mattered to everyone.

She was vilified.

She was called a home wrecker and a foreigner because he was a married man with children.

So word of this got out, and it got out in the wake of a highly important physics meeting where only the top physicists in the world were invited to attend.

She was there.

She was the only woman in the room.

And Albert Einstein was there.

Ernest Rutherford, a few people you’ve heard of.

Rutherford discovered the nucleus of the atom.

These are some heavy hitters.

Heavy.

Big time.

So she’s vilified and the cheating husband is not vilified.

Right.

Right.

He’s a victim.

Oh, he’s a victim.

Oh.

It’s the harlot scientist.

Of course.

You know, she’s a foreigner.

And she had recently tried to gain election to the Academy of Sciences.

So people get jingoistic.

She’s a foreigner.

Right.

She’s a homewrecker, a man married with kids.

Right.

And…

He’s a victim.

So what happened at the meeting?

And then what happened with the Nobel Committee?

Well, the meeting was already over.

And Einstein wrote to her, outraged, that she had been pinpointed this way and said, he’s sorry that the rabble was concerning itself.

And he thought very highly of her.

Yeah.

That sounds…

See, that’s great.

Because his deal is, what does any of this have to do with science?

The Nobel Committee decided that maybe it would not be a good idea for her to come to Stockholm to accept the prize in the midst of this scandal.

Wait, would they have given her the prize even if he didn’t show up?

I think so.

So they just didn’t want the media circus.

Yeah, just the whole…

Or the circus that would unfold.

Because they wouldn’t be asking about…

That would change the mood of the ceremony.

The mood of the ceremony.

But at that…

And she had offered at first not to come.

And they told her, no, no one here believes the lies.

But then they changed their minds and asked her not to come.

And she said, I failed to see any connection between my scientific work and scandalous attacks on my private life.

And she went to Stockholm.

However, I will say that the illicit sex that I’ve had with my lab partner is indeed radioactive.

No comment.

There’s a novel inside Chuck somewhere.

I’m trying to get that out.

So she went and got the prize.

She got the prize, yeah.

And she took her daughter with her.

So, Iran got a foretaste of her.

Hey, I’m gonna think I’m gonna come by here in 20 years.

I’m gonna come back.

25 years, I’ll be back.

I’ll be back.

Watch me.

So your book, who published the book?

Grove Atlantic Monthly Press.

Oh, okay.

And it’s out now?

It is.

It is out now.

All right, so is this a movie ready to be made?

Sounds like one.

Does someone buy the movie rights?

From your lips, Neil.

I saw recently a play about Marie Curie.

Yes, there have been plays, there have been movies.

But as I said, this is a different story.

We’ll see what happens.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Do you remember her on the mural?

Of course you do.

The huge mosaic at the front entrance of the Bronx High School of Science.

You walk under that every single day.

And it’s very biblical in its scale and in the posturing of the characters.

And every single character is a mathematician, a scientist, or an engineer.

And one of them is Marie Curie, prominently featured.

And she’s the only woman there.

Yeah.

And she’s there looking at a test tube or something chemical.

And we’ve got like a Galileo figure, a Newton.

We have Imhotep, architect of ancient Egypt.

All these folk.

And you walk under that every day.

And you say, yeah.

One day I’m going to be on that mural.

That’s cool.

That’s fantastic.

It seems to me, everything Marie Curie touched in and around her lab might still be radioactive today.

Is that true?

I’m sure it is.

Okay.

How about her notes, her clothing, her effects?

Yeah.

Radium has a half-life of 1600 years.

Oh, well, there you have it.

That’s it.

1600 years.

They remind people about half-life.

So whatever how much radium you have today, in 1600 years, you have half that much.

Right.

And then 1600 years, you have half of that.

Half of that.

So 3200 years, you’ll have one-fourth of what’s sitting in front of you right now.

So clearly that’s…

So you day it.

What did she die of?

She died of aplastic anemia.

So her body could no longer create red blood cells.

Partly radioactivity exposure, but also x-ray exposure.

Because during World War I, she outfitted a van with x-ray equipment and drove to the front because it was going to be the first time that battle wounds could be x-rayed.

And she created a mobile x-ray unit for it.

Wow.

It was instantly obvious what the value of x-rays were when they were discovered.

Even so, she had to argue with some of the doctors who had never seen it because it was still relatively new.

Okay.

And so she created this car that had all the equipment and then because people were very quickly convinced and were willing to have something permanent wherever the field hospitals were.

So she set up a course.

She created a six-week course in x-ray, electricity, human anatomy, and she trained 150 French women to do that same work.

Wow.

So every x-ray technician owes her a debt because she created their job.

Yes.

Well, there were some before that, but they were coming up through the medical ranks.

Her feeling was, this is a crisis, and there are a lot of women who want to help.

Help.

And I can tell them what they need to know, and they can go and do it.

It’s amazing because you learn about Marie Curie, and they just say radioactivity, they say that.

Just at the short list.

The short list.

They’re like, radioactivity, Nobel Prize, woman scientist, and moving on.

You know, like, that’s it.

This is, I mean, I’m just absolutely gobsmacked by all the accomplishments of this woman, and what she’s responsible for.

When I started this book, the pandemic happened.

So I didn’t get to go to Paris, but what I discovered was that everything about Madame Curie has been digitized.

So her personal notebooks, the most touching of which is the grief journals she kept for a year after her husband’s death, in which she spoke to him.

You can read the whole thing online.

So you had access to digital records, so you didn’t have to expose yourself to what might be residual radium.

Well, I couldn’t even have the grief of going to Paris.

It was what I had to settle for, but I was fascinated by the wealth of the material.

You can read all of the weekly publications of the Academy of Sciences back centuries, and it’s easy to get at.

And then her notebooks, yes.

Okay.

It’s just honest.

You sold me.

It’s just free.

You had me at free.

Get up your French reading is the only thing.

It’s all in French.

Yeah.

Okay.

Yeah.

Of course.

Yeah.

Unless it’s just English and a really bad French accent, I’m screwed.

He does a Frenchman bad accent really well.

I bet.

I bet.

You always give them a cigarette.

But it does.

You have to have a cigarette.

Okay?

It is French law.

You do not want me to be arrested.

How soon we forget, or perhaps never knew, or worse yet suppressed, the contributions of so many people, so many scientists, engineers, seekers of cosmic truths, be it in a laboratory or in the sky, anywhere.

The number of people represented in that population is huge, yet we only ever read about a few of them here and there.

And somehow, some of us are prone to think the information, knowledge, discovery just somehow is handed to us from on high, from a tablet in the sky.

No, it’s hard work.

And scientists who are committed have done this often without reward.

The only reward is the act of discovery and the knowledge that the universe is knowable and you on the frontier, on that moving frontier, have contributed to that base of knowledge that we call science.

Marie Curie, among others, and all the women in her lab, and all the other labs that we have yet to hear about, because Dava Sobel hasn’t written about them yet.

Who knows how many labs lurk in our ignorance for us to get a full appreciation of the foundations of what we take for granted as modern science.

And that is a cosmic perspective.

So Dava, our first ever StarTalk guest, I want you to come back for every book that you write.

I want to write another one just for that one.

If you need incentive to go back to StarTalk, write another damn book.

I got it, okay.

Okay, you got it.

Thanks for being on the show.

Chuck, good to have you, man.

Always a pleasure.

All right, this has been StarTalk with our inaugural guest returning, coming back to us.

In this, the 600th episode of What She Started as episode number one, Dava Sobel.

Thanks for coming back.

Neil Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist, as always.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron