About This Episode

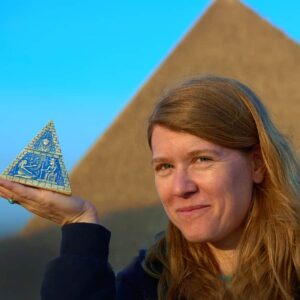

Who really built the pyramids? Neil deGrasse Tyson and Chuck Nice learn about space archaeology, LIDAR, and discovering tombs, pyramids, and new Nazca lines with space archaeologist Sarah Parcak.

Discover how archaeologists use space technology to find archaeological sites. Why are we using satellites to see stuff we can go to? We explore LIDAR and using the near-infrared to uncover tombs, pyramids, and more hidden under the rainforest.

Find out how anyone can use NASA satellite data to discover archaeological sites. We discuss false positives and the time Sarah almost ignored a strong signature and nearly missed finding a massive Viking hall. Plus, learn about layered cities and how many Egyptian archaeological sites are left to be found.

Learn how citizen space archaeologists helped discover new Nazca lines in Peru. Sarah shares her response to people who think the aliens built the pyramids and why you shouldn’t substitute imagination for science. We talk about the possibility of finding fossils on the moon from ejected Earth rock, The Drake Equation, and studying the Space Station. Plus, what is the most common thing archaeologists dig up across all cultures?

Thanks to our Patrons Bo Cribbs, Anna Wheatley, Fred Gibson, David Griffith, Micheal Richards, Advynturer, Vici Bradsher, Terry Migliorino, Lingji Chen, and Audrey Lynch for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTChuck, I think everyone should have their own personal archaeologist.

Is it Indiana jones?

Yeah, I’ll take that.

You just never know when you need one.

That’s true, exactly.

You never know when you’re gonna end up on a dig and just be curious.

Just be curious.

What’s buried here?

What is that and why?

yes, exactly.

I need an emotional archaeologist is what I need.

Dig into your mind.

I’ve just been burying so much over the years.

All right, a little bit of space archaeology and more coming right up.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk.

Neil deGrasse Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist.

Come with me, Chuck Nice.

Chuck, baby, how you doing?

What’s happening, Neil?

How’s it going?

All right, we got a topic today we’ve never covered before.

yes, that’s correct.

We’ve been doing this for more than a dozen years.

More than a dozen years.

It never come up.

Today we are devoting to space archaeology.

Oh, look at that.

Okay, just to be clear, it’s not going to the moon digging up fossils.

Because there’s none there.

Well, there could be a reason for that, but we’ll get to that later.

This is specifically using space assets to help the archaeologists do their job.

Oh, okay.

So basically, they just hijacked your field.

That’s what they did.

They jacked your equipment.

They satellite jacked you.

I think they had permission.

It was not a gunpoint.

So we combed the world, and there are people who are experts in this, and we found Sarah Parcak.

Sarah, welcome to StarTalk.

Thank you.

Thank you so much for having me.

I’m thrilled to be here.

And I’d pronounce your last name correctly.

Hard C, Parcak.

Parcak, correct.

Sarah Parcak, archaeologist, Egyptologist.

Egyptologist.

That always sounds so cool.

You were a PhD in this from the University of Cambridge back in 05, and now you’re a professor of Anthropology, University of Alabama, Birmingham.

And I love this, founding director for the Laboratory for Global Observation at that university.

And recently you have a book, sensibly titled Archaeology from Space, How the Future shapes Our Past.

Henry Holt.

We share publishers in that name.

Oh, cool.

One of my recent books is from Henry Holt.

And is this true?

You wrote a textbook, the first textbook on satellite archaeology, which means you wrote the book on the subject.

I actually legit wrote the book.

I did.

Wow.

Okay, subtitled Satellite Remote Sensing for Archaeology, published by Rutledge, a good academic publisher there.

And founder and president of Global Explorer, EX spelt just with an X, a not-for-profit company using tech to protect and preserve cultural heritage.

I want to learn more about that at the moment.

And you’ve also collaborated with NASA and the US State Department.

So you are the right person for any question we might have on the subject.

So let’s get right in.

Since you did write the book on this, what is space archaeology?

Just put us on the same page here.

Sure.

So space archaeology is the use of sort of a general fun description or term for any use of space-based assets to map archaeological sites, whether it’s NASA satellites, commercial satellites, drone imagery, data taken from airplanes.

It’s any kind of remote information that you might use to locate, whether it’s a whole ancient archaeological site, whether it’s a specific feature on a site, or whether it’s looking for things like buried ancient river channels that may show how and why ancient settlements moved over time.

And you know, that can be called satellite archaeology, remote sensing for archaeology.

But actually NASA has a space archaeology program that funds scientists to do exactly what I do.

So I figure if NASA calls it space archaeology, then it’s a legit name.

Okay, so Sarah, you need some more convincing for me of what you do.

Only because when we use NASA to look at other planets, their surfaces and the like, it’s because we can’t go to the planet.

So we need space assets to zoom in in places we cannot go.

And so now you’re telling me that a satellite either parked at 23,000 miles up or orbiting hundreds of miles up is somehow going to serve you better than you just put your ass on location with a trowel.

So tell me why one is better than the other.

So that’s really the fun part.

And the whole point is to get somewhere on the ground, to do survey, to do mapping, to do excavation.

But anytime you’re doing archaeology, if everything were already visible, we wouldn’t need to dig, right?

So these are features, these are entire cities, these are pyramids, these are tombs that have been covered over time by sand or soil or dense rain forest.

And so what the satellites allow us to do is whether, you know, whether we’re using different parts of the light spectrum.

So think of it like a space-based X-ray or MRI.

We’re able to look at an archaeological site and we see these subtle differences on the surface because of how the surface soils or sand or vegetation is being impacted by what’s buried below.

We’re able to get maps of what’s there.

And so, you know, think of like a dense rainforest that’s covering an amazing site like an Angkor Wat, where you go there on the ground and it looks like the site is, you know, pretty big.

But when you map it using lasers and you can do point cloud data and remove all the overlaying vegetation just by using laser data collected from airplanes, you’re able to see the site is two, three, four, five times as large as you previously thought.

So really, that’s the strength of satellites.

They allow us to see size, scale and extent of sites and better plan our seasons so that when we go there, we know exactly what we’re looking for.

What you’re saying is, not to put words in your mouth, you have vegetation penetrating bands of light.

Because obviously, if you’re there, you have to cut through the brush and bramble.

But certain forms of electromagnetic spectrum cut right through that, saving you that effort.

Right.

So we use different technologies in different places.

So for example, where I work in Egypt or any kind of open area, whether it’s Morocco or Peru.

There’s no jungle covering Egypt, last I checked.

No jungle.

So most of the archaeological sites are open and exposed, but the sand is covering the foundations of a temple or a tomb or a pyramid.

And so what the satellites allow us to do is looking at, for example, let’s just say it’s a large settlement and it’s made of mud brick.

That mud brick, even if it’s foundation, is going to hold moisture differently than the surrounding soils.

And what the satellites allow us to do using the near-infrared is map these subtle differences that are completely invisible to us with our normal visual eyesight.

And so just near-infrared, so we have the visible spectrum, and then there’s this big band of infrared off to the side of red.

And I’m fascinated that we use these sort of proximal words, near-infrared and far-infrared.

It’s a weird fact, but near would be like closer to the red, and far-infrared would be farther away.

But what does near-infrared do for you that far-infrared does not?

So near-infrared is the best part of the light spectrum to map differences in vegetation and vegetation health.

You know, when I’m explaining the light spectrum to my students, you know, it’s so important because vegetation health can be impacted by what’s buried beneath it.

So it can be healthy or unhealthy depending on if the roots are going into, you know, mud brick or dense stone, or maybe it’s in a ditch.

Or even I’ve heard about some soil contamination can be up taken into the plants.

Right.

And you can see regions of plants that are just simply different from other surrounding regions, right?

I believe they call that Monsanto.

I’m joking, Monsanto.

I know you’re listening.

I’m joking.

You’re now owned by Bayer, so you’re fine.

Okay.

So we’re able to see leaves, right, in the green part of the light spectrum, because that’s the information that is transmitted from them.

That’s what we, from the light.

But it absorbs.

The sunlight, right, from the sunlight.

But it absorbs the infrared.

That also is important, right, because we have to use computer programs to discern these differences that we can’t otherwise see.

So when you’re looking at that from a satellite, in the infrared, if you see brighter leaves, does that mean they’re healthier or if they’re dimmer, they’re not as healthy?

Is that how that would work?

So that’s exactly right.

So healthier vegetation, we see a brighter response, so it’s going to have a higher value.

And that’s what we look for in less healthy vegetation.

We don’t see the same information.

But actually, Sarah, isn’t it true, you’re not there to value judge it, you’re just trying to find differences.

Right, yeah, I mean, it could indicate a wall, it could indicate an underground water source.

We don’t know, right?

But if it’s a linear, so it’s interesting though, like thinking about what we see and what we don’t see and false positives.

There was one time where I was convinced there was nothing there.

And it was actually a real positive that I thought was a false positive.

That there was a very strong signature of healthy vegetation that was found in someone’s backyard on this little island called Papa Store in Scotland.

And they’d been finding Viking objects in their garden for years and years and years.

And so this very strong signature showed up and I said, it’s in alignment with their house.

And typically when you see that, it’s like a buried water pipe or a gas pipe.

And I dismissed it.

I said to the team, we’re not going to check that out, right?

It’s modern.

But the team didn’t listen to me.

I was collaborating with local archaeologists.

They’re like, I think you found the Viking structure.

I think that’s what it is.

I’m like, no, it’s not there.

Could you listen to me?

I’m the expert.

When I showed up, they’re like, yes, so why don’t you check it out?

It was this massive Viking hall that was inhabited over hundreds of years by royalty and a king may have visited.

I was happily wrong to be wrong.

This is science, right?

sometimes we’re really cautious.

sometimes we need to throw a caution to the wind and go with a super positive healthy vegetation signature that turns out was a Viking wall.

Tell me about LIDAR.

We’ve all heard LIDAR.

We know RADAR, right?

Which is, of course, an acronym for the earliest…

How you get a ticket.

It’s one of the earliest ever acronyms.

Radio-Ranging, Radio Detection and Ranging.

RADAR and radio waves, but the smallest versions of those radio waves are microwaves.

That’s what the police used for your…

It’s still collectively radar.

LIDAR, is that just visible light?

LIDAR stands for Light Detection and Ranging.

It sounds like something you might see in a Marvel movie.

A sensor system is flown on, whether it’s a helicopter or an airplane or a drone, and it sends down millions of pulse beams of light.

And if you imagine you’re in a dense rainforest, you’re in the middle of the heart of, whether it’s Cambodia or Brazil, anywhere in the world that has this dense vegetation.

It sounds like you get around.

Yeah, man.

I do get around.

I do get around.

It’s a good thing my husband’s upstairs, so.

But yeah, he could confirm.

I do get around.

And you’re in the heart of this dark…

I make a lot of jokes.

Just let it go, Sarah.

I was like, I’m gonna…

I’m not going to respond.

We gotta let go, Chuck.

I’m gonna let that happen, you know?

So, you’re in the heart of dense rainforests, but even when you’re in the densest part of the rainforest, you still see light coming through.

And what the LiDAR does is, you know, maybe hundreds of thousands of pulse beams of light hit the uppermost parts of vegetation.

You know, hundreds of thousands hit the middle.

Hundreds of thousands ultimately will hit the rainforest floor.

And you end up with a 3D point cloud model of the entire landscape.

And what software allows you to do is to remove all the dots that are above the ground.

And you’re left with what’s known as a bare earth model or a digital elevation model.

And if there’s a pyramid or canals or terracing, any kind of structures that indicate ancient settlement in that area, they are going to be obvious and clear in a way that isn’t, even when you’re walking through the rainforest.

Or maybe you might say, OK, I can see the hint.

Maybe there’s a structure here, but you’re not going to know exactly what it is.

And that’s that’s what the light are doing.

You know, there’s really this light are revolution.

But don’t you need that at different angles through the vegetation?

Because if you just go from one direction down and up, you just maybe get in the canopy, you’re not going to get the canopy.

You’re catching it at different angles as it goes along.

And so you end up with millions and millions of points.

Oh, I see.

Because it’s passing overhead.

And so if you constantly get the data, then I see.

And the point is to use a sensitive enough system, a powerful enough system to actually go through and get a certain number of points per square meter on the ground.

You actually need, you know, between five and 12 points per square meter on the ground.

And then you have very high resolution data.

Topographic data.

You have for topographic data.

And then you can create these models.

And, you know, for example, my colleagues at Tulane University just used LIDAR.

In New Orleans, New Orleans.

Correct.

yes.

They just use LIDAR data and they found 80,000 previously unknown structures and features around Tikal.

It was in Science, a huge paper in Science.

In Science magazine.

yes.

Hi, I’m Ernie Carducci from Columbus, Ohio.

I’m here with my son Ernie because we listen to StarTalk every night and support StarTalk on Patreon.

This is StarTalk with Neil deGrasse Tyson.

How do you get below ground, like a tomb, or if you’re talking about pyramids, a lot of the pyramid for the burial parts are underground.

So how do you get that?

So to what Neil brought up earlier, so depending on what features you’re looking for and how deeply they’re buried, we can use a couple of different kinds of data.

So we can use radar data.

So that will pass through.

penetrates, right?

That penetrates not very far, not as far as you think, maybe a couple of meters.

It has to be in dry environment.

So it works really well for detecting things like very river courses, where you’re looking for old settlements from maybe 10,000 years ago deep in the Sahara.

You can also use thermal infrared data.

So this is the next part of the light spectrum.

So you’ve got the near middle far infrared and then you’ve got the thermal infrared and that measures heat differences.

So for example, let’s just say you have a buried chamber or a buried tomb where the temperature is different, you’re going to see that void that has a slight temperature difference and know.

You’ll know that there’s an opening there or there’s a space.

Well, I think generally when we think of infrared, we only ever typically think of temperature.

I’m predator.

Yeah, but infrared is light just like any other part of the spectrum.

And if you know in advance, you’re trying to find subtle temperature differences, then infrared, that’s your choice, right?

And the other thing that we use is what I was talking about earlier, which is what’s known as active satellite data.

So you have active and then you have passive, excuse me.

So passive is the most of the satellite data that I use.

So it’s receiving light that’s reflected off your surface.

It’s not sending data down like LIDAR or radar, it’s receiving that information.

So that’s where we’re using different parts of the light spectrum.

So the near middle and far infrared to look at things like vegetation differences, soil differences, water differences.

And then we’re using pretty standard off the shelf remote sensing software.

So we can just get it anywhere.

We can get it anywhere.

Like a TurboTax, you know, just all over the place.

And the great part about so much of the data that I use and my colleague use, it’s free.

You know, NASA has put millions, tens of millions now of their satellite imagery data sets online.

And that’s for kind of, you know, larger areas.

But the commercial satellite data, you know, you can easily get a satellite image of an archaeological site in the surrounding area for a couple hundred dollars.

So it’s not free, but also it’s not going to break the bank either.

You know, Sarah, in my day, we had to actually go to the sites.

I just want to say, you know, you young next to me.

You can’t hate on the fact that they found a smarter way to work.

So once we have all this data, right, you know, whether you have, you know, your area that you’ve mapped, there’s a hundred potential archaeological sites, or maybe there are features on the site, we then have to do the really fun part, which is called ground truthing.

So we then go to these sites, we go to these places, and instead of spending, you know, six months in the field hacking through rainforest or months and months of looking for things and hoping we find something, we’re able to have a very targeted approach.

We know exactly where we’re going.

You know, today we are going to check out these 10 places and with government, you know, cuts to funding, with having to really optimize our time in the field, it’s an enormous time saver.

That’s like playing poker with a marked deck.

That’s kind of what you’re doing.

Why do people crash, Chuck?

This is noble work here compared to a poker game.

Plus just the concept of a ground truth, I think has its origins in the military, where you would fly over some region and you’d think something was the troop movement or enemy movement and you’d have someone on the ground verifying that who was right up close.

I was ready to go back and say, you can’t handle the ground truth.

And you know, it’s interesting too.

Did you know that aerial archaeology is the reason that we have all aerial reconnaissance in the military?

It started in World War I when the first military planes were flying over Syria.

There were amateur photographers from France and England, and they would take pictures of archaeological sites because they were archaeologists and hobbyists.

They showed these to their commanders, and they went, wait a minute, you can map things from the air?

Oh, thank you very much.

Then the funding flowed like rivers.

Right, yeah.

So Sarah, if LiDAR uses light, it seems to me lasers would be a very good source of light for this because you need the intensity and you see the reflected signal.

I’ve used three different color lasers in my life, a blue, a green and a red.

All illegal.

Every single one of them.

Just because, Chuck, don’t tell people.

So I would imagine that different color lasers, because lasers is monochromatic light, would serve different questions that you might have for the terrain.

As far as I’m aware, the lasers that are used for light are pretty standard.

So the data we get from the lasers is the point cloud data.

So there’s no specific spectral information that’s contained within that.

You’re only using it for the topography.

Got you.

And when you go to the site, so you’ve identified it from the air, and you say, okay, we have these 10 sites.

When you go to them, are you trying to establish that you’re going to now move on to excavation?

Or are you just trying to figure out if there’s something viable?

What do you think?

She’s just gonna stay home?

You think?

You think?

Really?

Really?

I’m just saying, is there any, do you ever come up with a dud?

It’s like, when you’re drilling for oil, there are a lot of times you think that you have found an actual viable site to drill, and nothing’s there.

In the old days, that was much more common, Chuck.

Of course.

Now, the geophysics is way better today, so wildcat drills is way more efficient than…

Because of her.

That’s why it’s more efficient.

They’re actually using the exact same technology that Sarah’s talking about.

But I’m saying, for your purposes, do you ever come up with a dud?

When I first started, when I did this as part of my PhD, it’s science, right?

We have to be critical about what works and what doesn’t work.

And when we go into the field to check, maybe 85 to 90 percent of the time, there’s a thing there.

There’s an archaeological site and maybe one out of 10, oh, I thought it was a site, but there’s this thing here and said, okay, why am I getting a false positive?

And then we refine our methodology and go back.

But it’s come a long way in 20, 25 years.

And so when I was doing my thesis, high-resolution satellite data was five to $10,000 for a single image.

I had to rely on the cheaper, lower-resolution NASA data.

And now we have Google Maps.

You were spending 10 grand a picture.

Now it’s 60, you’re only pulls it up on their iPad.

Yeah, I know.

My son’s like, Mommy, you missed one.

But I wish I were lying, but he’s done that to me before.

But this means that data, there’s this great democratization of information now.

And we have so much more to go through.

And whether we’re identifying something visually or identifying something using algorithms, using different parts of the light spectrum, it means we have to go back and reanalyze all of our data because of what we missed.

So sometimes when we go into the field and you say, okay, I think what I have found looks like a pyramid, right?

It’s the same size and shape and extent.

But maybe when we excavate it, okay, it’s not a pyramid, it’s a huge tomb.

That’s not an L, like that’s still a W.

L or lost, W for when?

yes.

Okay.

To get the lingo.

I speak an 11-year-old now.

My son tells me, take the L, mom, take the L.

It’s in the W column.

I took an L, but today I bounce back.

Okay.

But the other nice thing about satellite imagery, especially high-resolution imagery, if you’re working in an area like Egypt, where maybe you’re in Saqqara, it’s pretty well excavated.

There are hundreds of known tombs, and you’ve got 300 discrete features that the satellite image has helped you to identify that don’t look like there are any previous excavation reports.

We have all this data, so in archaeology, we go from the known to the unknown, and so we look at the tombs from the third dynasty, fourth dynasty, fifth dynasty, the pyramid age, the age of the pyramids at Giza, and we look at their size and shape and orientation and relationship to one another, and we’re able to make pretty good guesses as to what the things are that we have found.

So maybe our grant from the National Science Foundation is to explore economic mobility of upper-class individuals in the late old kingdom.

And so we want to excavate tombs from dynasty six only.

So that satellite data helps us to target what areas to excavate.

Are there satellites that will help you find the lost city of gold?

Because that’s what’s truly important here, Sarah.

No, no, Atlantis, Atlantis.

So, Sarah, I wanted to pivot to Egypt, because that’s one of your specialties.

I have to ask a very blunt question.

Please.

What hasn’t been excavated there?

What is still there to learn?

It’s been there for thousands.

What’s taking you guys so long?

Why isn’t everything known?

What is going on here?

Plus, it’s not like Egypt was lost and buried and then discovered like Pompeii.

Egypt was always sitting there.

Ancient Egypt was always there.

What does it mean to have a new discovery when we have a continuum of occupation and presence and awareness of that archaeological site?

If you think about how long ancient Egypt lasted.

We’re talking about a civilization that at its height lasted for approximately 3,000 years.

But it, of course, continued after with the Roman Empire and then Muslim invasion and then medieval period and so on.

But it came before then too.

Egypt had its origins deep in the western desert.

You have 7,000 plus years of occupation.

But in the Nile Valley, if you think, generally speaking, there were around 2-3 million people who lived there over that 3,000 year period.

The Nile is continuously depositing silt every year, which is causing the landscape to rise.

So imagine cities and villages and towns and tombs and temples and pyramids for 2 million people over a 3,000 or more year period of time.

That’s a lot of places to find.

A lot.

All right.

I’d appreciate it that it would be that many people.

So can I ask you this from what you just said?

And it’s always puzzled me.

It’s one thing when you talk about waterways that are shifting and depositing silt and creating layers upon layers.

But then you see these dig sites that are in the heart of the city where people are still living and buried beneath that city is a whole nother city.

How does that happen?

What did they just go?

Look, we need dirt because we are tired of like, let’s just bury this and build on top.

What happens to create?

And then like when they uncover its full structures that are intact and their interiors are intact, what happens?

Is it tragedy?

Is it some kind of disaster?

What causes that to happen?

So some cities in the world, you both have traveled all over the place and there are these magical cities that have these old vibes, whether it’s Athens, whether it’s Istanbul, whether it’s Paris, whether it’s Cairo, ancient Rome.

Yeah, Rome itself, yeah.

Ancient Rome, I’m walking in the building and so, oh, by the way, over here, the floor is glass so you can see crypts that happened to be.

Meanwhile, I’m just trying to get a doughnut from the.

That was the OG crypto, right?

So you have these, I call them layered cities.

They’re places that were great to live thousands of years ago, and they’re great to live today.

They’re everywhere, right?

Look at what happened during the Olympics in Athens.

They had to construct the subway and it took them years longer.

They barely finished it in time because the whole process was an archaeological excavation.

So we as humans like to live in the same places, right?

So we call them palimpsest, so these layers and layers and layers of occupation.

It’s probably because the climate was good or the water supply was good, or there’s some feature that you’re not going to go into the hills to escape just because somebody lived there before you.

Or a place like Istanbul, which is perfectly located, it separates Europe and Asia.

Trade, commerce, access.

Always a crossroads.

Yeah, a crossroads, right?

these crossroads, places that are magical, and it speaks to the great continuity of humanity.

So I wondered, I got asked that question all the time, Neil, that you asked me a couple of minutes ago, like how much is left?

How can we possibly be sure?

So I took all the sites that I found as part of my PhD, so hundreds of sites across the Delta.

The Nile Delta.

The Nile Delta.

Okay, not Delta airlines.

No, not Delta airlines.

And I combined them with the hundreds of known archaeological sites in the Egyptian Delta.

I then looked at all the known excavation data for all the sites, and I calculated their area and volume.

And as it turns out, in the Egyptian Delta alone, we have excavated one one thousandth of one percent of the sites.

That’s the answer.

Wow.

That’s the answer.

We know we know this much.

And we know nothing.

Egypt, we know nothing.

And this is why all over the world, all the time, we keep making these amazing discoveries.

Sarah, get back to work.

What are you doing on this show?

I’m slacking.

I only found 100 sites this morning.

I know.

I got to go.

I got to pick it up.

does my next question dovetail into your global explorer project?

And let me just see if it does.

So if archaeology is no longer the province of professional archaeologists, because you are accessing the same data on the cheap as anybody else can access with a computer, has that turned the world into a raging circus of amateur archaeologists, each sure that they’ve made a new discovery?

So, yes, to your question.

What is the answer?

So, you know, anyone with a computer can look at Google Earth.

You know, it’s on everyone’s phones if you want it.

Everyone from the age of four, five, six, you know, whether they want to find mummies or pyramids or dig up dinosaurs, everyone grows up with a passion for the past, which is awesome.

You have to compliment to your fields, right?

Right, yeah, there’s nothing like, I want everyone excited about archaeology because, let’s face it, massive cuts to the National Endowment for the humanities, National Science Foundation, you know, museums are undergoing funding cuts, anthropology departments are closing in the US and other parts of the world.

If the public is interested and passionate and understands the role that the past can have today for helping us to understand climate change and war and, you know, give us some hope, which we need more of, then that’s only good.

We want people participating but participating in a guided way.

So this is one of the reasons that I started my not-for-profit Global Explorers.

So back in 2016, we built an online citizen archaeology crowdsourcing platform.

So this gave some structure and an umbrella under which this activity can unfold.

So it’s not just random at this point.

No, so we started the platform with archaeological site data from Peru.

So we had the full buy-in from the Ministry of Culture in Peru.

We were collaborating with a number of Peruvian archaeologists and specialists.

That means you have the Nazca lines and the Nazca patterns on the plains of Peru, right?

Correct.

Yeah.

So the data that the crowd used and the data that the crowd generated.

So the crowd ended up finding almost 30,000 potential, we called them anthropogenic features.

So suggestive, we were very careful.

So we then looked through all the data and over 800 of them were determined to be significant previously unknown discoveries.

So these are sculptures or structures or paintings or some surface features on earth.

So for settlements, potential tombs, suggestive structures that are on the earth’s surface.

We then gave that data to colleagues in the region of Nazca.

Looking for the sites that the crowd found, they found new Nazca lines.

So this collaborative project helped to support great local archaeological work and gave them a new perspective and allowed new discoveries to be made.

So that’s where we want the data to do.

We want to harness the power of the crowd and everyone’s passion.

And some people got really, really good at finding sites and features.

We had some super users that found hundreds of features.

And then that can help people on the ground who have the qualifications to go out and excavate and map.

But there’s still renegades out there, for sure.

And what do you do about people whose imagination is put forth as a substitute for science?

I believe that’s called America.

I believe you just described the entire country.

That was a damn good sentence.

I don’t even know if I can repeat that.

So we’re having a moment right now in our country where the value of experts and expertise is coming under fire.

It was exacerbated, of course, by the pandemic.

There’s that famous, I think it was a New Yorker cartoon, some guys on an airplane.

And he’s like, come on, we can pilot better than the pilot, let’s go.

And you’re like, what?

And so, archeology, that’s not real.

I can dig.

Digging is what my toddler does.

So people don’t understand or appreciate that it takes years and years, decades of training.

I’m still learning.

Every time I go into the field, I’ve been doing this for 25 years.

I’m still learning.

Otherwise, you regress.

If you’re not learning every day, you might as well move backwards.

And people like me get accused of gatekeepers.

You think you’re better than everyone else just because you know how to dig.

It’s like, if I have a problem with my heart, I want a qualified heart surgeon.

I don’t want Edna on Facebook to tell me to take herbs.

There’s a YouTube video that you can just operate on your own heart.

I saw it.

And who needs a YouTube video?

I like to feel my way through these things.

It’s vibes, man.

I have a feeling.

I got the right cardiology vibes right now.

Yeah.

I just have a knife.

I have some rubbing alcohol.

I don’t want to discredit people’s passion.

There are so many great people online who are excited.

They’re enthusiastic.

They have good ideas.

They just don’t have the training.

They don’t have the framework.

And I wish more of them would take archaeology classes because I think they could all make real contributions to the field that are valid.

The problem is that your archaeology classes, they don’t support the fact that everything you dig up was put there by aliens.

Sarah, I don’t know if you know this, but everything that you guys dig up was put there by aliens.

The previous civilizations.

Right, exactly.

And isn’t it interesting?

Egypt, Central America, Peru, Peru, right.

Great Zimbabwe, India, it’s all aliens, but Rome, Europe, Stonehenge, I don’t know what that could be.

As much as I loved the movie Stargate Atlantis, it still had the pyramids built by aliens.

Right.

The Africans somehow didn’t have that ability.

You need to be aliens.

And what I tell people, I was at a lunch years ago with some interesting people.

And they all said, like, well, come on, aliens, right?

You can’t go to the pyramids and look at the pyramids and be like, how is this done by humans?

I’m like, okay, fine.

Give me three minutes.

Give me three minutes.

I will prove that the pyramids were not built by aliens.

Oh, please, can you do that?

Yeah, okay.

So I pull out my phone.

I pull out my phone.

First you have to punch him in the face.

Yeah, do a victory dance.

So I hold up my phone.

I’m like, was this built by aliens?

They’re like, what do you know?

Steve Jobs and the iPhone.

I said, so you go back whatever 5,000, 6,000 years in Egypt and first steps, they put their dead in the ground.

Is that aliens?

We’re like, no, that’s normal.

You bury your dead underground.

I’m like, okay, well, then dogs dig them up and start eating them and that’s gross.

You start putting stones on top of them to protect them from dogs.

Is that aliens?

They’re like, no, that’s again normal.

I’m like, right.

Things develop and their social stratification and soon, the wealthier people, the leaders, you bury them with pots and goodies.

But still, there’s stones and aliens?

No, still no aliens.

Well, then they start getting fancy with the stones and they start building superstructures and making a little more formalized and society gets more organized.

That aliens?

Well, no, that’s normal.

Okay, well, things start getting bigger.

We’re able to see this in the archaeological records.

Soon, there’s more chambers and more stuff.

Is any of this aliens?

No, still no aliens.

All right.

Well, so they get bigger and bigger and bigger over a 500-year period of time.

Soon, they’re building huge structures out of mud brick.

Aliens?

No aliens.

And I said, and then along comes Imhotep, the genius architect, the Steve Jobs of his time.

And so he takes this very large stone-built tomb where we see hundreds and hundreds of examples going back 500-plus years.

And he looks at it, he’s like, yeah, I’m not gonna be extra.

I’m gonna stack them one on top of the other.

And I look at them, I’m like, what does your three-year-old do with blocks?

Well, he stacks them.

I’m like, right, just like Imhotep did.

That was the start of pyramids.

And then slowly over the next sort of 300 years, they get larger and more complex and eventually they get smooth sides.

Sure, clearly Imhotep was the alien.

That’s what was going.

So that’s it.

It’s human genius, it’s human innovation over hundreds and hundreds of years.

And it’s a progression that you see over a long period of time.

They didn’t land from space.

There was a prior story there.

So, Sarah, as in most branches of science, and particularly where very precise tools, tactics and techniques arise, often they can be applied in other ways.

And I can’t help but think that everything you’re doing here on Earth can now be applied when we’re mapping the moon or Mars or Venus.

Oh, that makes us the aliens.

We are the aliens.

We are the aliens.

We are the anuping on other planets.

So, in what way has your field or the technologies of your field, satellite archaeology in particular, been co-opted the other way now?

We’re just starting to have more and more conversations with planetary scientists, with NASA.

I’ve been kicking around some ideas with our wonderful colleagues at SETI.

And if you look at the Drake equation, right, when Frank Drake came up with it, we didn’t know how many exoplanets there were capable of supporting life.

And now, you know, there’s, I don’t know how many, there are hundreds.

Oh, we’re capable of supporting life as we know it.

Yeah, it’d be in the hundreds.

Hundreds.

Out of the catalog of, right now, rising through 6,000.

So.

So the question is, you know, as in when and if, but I think when, I believe there’s life out there.

But the question is, if there’s advanced life, what will it look like?

How advanced will it be?

And it could be that we find a planet where, you know, because of a catastrophe or whatever reason, you know, that civilization ceased to exist a million years ago, but it’s still there.

So what is it that we’re doing and how we’re mapping things on the ground that could help us to unwrap, un-shape, and decode what these places could have been like.

And archaeology is the way to do that, not necessarily through space archaeology, that will help us map it, but archaeology provides us a framework to reconstruct how entire civilizations evolve.

The huge intellectual capital of invested brains thinking about that.

Ways that the astrophysicists wouldn’t, we don’t think of civilizations in that way.

Who needs civilization?

Yeah, we just don’t have that training.

I mean, we’d love to bring you on board for sure.

I love jamming with other scientists because, of course, everyone’s got great ideas, and there’s so much that I don’t understand, appreciate, know about how and why things develop on planets.

And the idea being like, where could we find this life?

Could beings exist that have evolved to live in extreme temperatures, right?

Which is why we’re studying life around heat vents deep in the ocean.

What are different ways that we could think about life?

octopuses, they make houses.

Like, that’s amazing.

They construct their own little mini apartments.

Is that what an alien civilization would look like?

Like an octopus condo?

I don’t know.

But I think we could create tools to help people think about ways of mapping them.

This is how science builds on science.

Because not everyone can know everything going into a problem.

Even Einstein, who laid the entire framework for the discovery of black holes, did not even predict their existence.

Because it was outside of his thoughts.

And it was even a denial of it for a while.

I can’t stop thinking about octopus house warmings now.

No, because he’s got a house.

That’s a little fact that you just threw out there that, you know, we kind of let it just fly.

But I’m like, wait a minute.

Like that’s I have a completely different view of octopuses now.

You know, just like showing up to each other’s house with a little bottle of vino.

You know, just like, hey, nice place you got here.

A selection of eight bottles from the case of water.

Excellent.

Well done.

Well done.

So what does this say here about using archaeology to study the space station?

Is that a thing?

So that also is a form of space archaeology.

I think, you know, the idea that we can use this technology to view how other places are inhabited and how and why it changes over time.

You know, my colleagues who are studying the space station and moon artifacts, it’s amazing work and so essential to understanding.

Because for now, like, that’s all we have.

We have the space station.

We have to figure out what do people leave behind?

What’s the ephemeral evidence?

What are things that we need to consider?

And it’s fascinating.

So it’s a space version of your multiple civilizations.

Because the ISS has been up for 25 years or 30 years or so.

I was being assembled in the 90s and a different nationalities are there.

They eat different foods.

So are you referring to the run of human culture as it has been expressed in that space?

Yeah.

And changing technologies, innovations, breakages, additions, studying how the space evolves both from the outside and also on the inside.

Right.

Where did they put the 286 computer?

Did they bring it back to Earth?

Did they just stick it outside so it’s still floating by?

Right.

As times modernize, old things become obsolete.

And what do you do with it?

And it’s all just contained there.

If not brought back, that’s pretty well.

One thing I was going to mention earlier, people have considered looking for fossil remains of life on the moon from ejected rocks from asteroid impacts on Earth.

Oh.

And then they would float through space, because we have moon meteorites on Earth that we didn’t have to go to the moon to get.

Really, the moon has been hit before, and so rocks get cast into space.

Some arrive on Earth.

So we have huge supplies of moon meteorites here on Earth.

And if that’s the case, presumably there would be Earth meteorites on the moon.

And then you go there and look for any stowaway microbes, not thriving on the moon, of course, but there would be evidence of them having once existed.

So, any of your people thinking about that, Sarah?

No, I, wow, I mean, you, it’s the first I’ve heard of it, just because it saw its size.

It’s very inventive, yes.

Yeah, it’s awesome.

It’s super cool.

I mean, I, you know, the question is, like, what size would they be?

I know that the moon is incredibly well mapped at a very high resolution.

So the question is, you know, where could they be?

Are there places that they would, where we’d be more likely to find them?

Yeah, and how much of that meteorite would remain intact upon colliding with the moon?

So there are other factors here.

But once we learned that rocks move between planets, this became a very easy next thought to have about, and by the way, and the fossil record going back to the moon would, if it was preserved, would be intact over the thousands, millions, and even billions of years it’s been sitting there.

Because there’s no erosion, there’s no weather, there’s no subduction of continental plates, it’s just there.

And so maybe that’s another frontier.

And the question I would have is, would those rocks, would they have a discrete spectral signature compared to the surrounding?

When they would pop out, then they would just reveal themselves.

Right.

So we just need one.

You are being lazy again.

Let me just sit back and think about it.

Smarter, not harder.

But I think that’s an amazing idea.

Like I would love to help with that kind of project.

Yeah, cool.

Very cool.

Hey, is there a thread that as you span the globe that is the most common thing amongst the cultures or civilizations that you dig up?

So that’s a wonderful question and no one’s ever asked me that before.

And it’s the subject of a book that I’m working on right now.

So the book sort of inverts the idea of collapse and is a very hopeful look at how and why humanity lasts.

So the thing I think that connects…

Humanity or civilizations, local civilizations?

Humanity, humanity generally.

The idea of continuity.

That is the thing that connects so many of these sites and places that I and my colleagues have mapped all over the world that wherever you go, people last and, you know, kings may stop ruling.

There may be environmental change, climate change, war, disease, but culture persists, people persist.

And to me, the idea that so many of these places today, to the point earlier that like so many cities are built on top of old cities, we last, we persist in spite of all of these awful things, some of which we have no control over, some of which we have great control over.

And it makes me very hopeful in the face of all these awful things that we’re staring down now with climate change, with war, with the rise of authoritarianism.

So the work I do gives me hope because of how long we’ve lasted and where we’ve lasted.

Wow.

That’s a tone to end the show on right there.

Anything that gives us hope, I’m all in.

Tell me about it.

Bring it on.

Please.

Give me some hope.

Oh my gosh.

Anyway, it’ll be out in a couple of years, so I’m working on it now.

Cool.

All right.

Well, good luck on that.

sometimes you need a little bit of luck when writing and publishing a book.

Especially when it’s about hope.

In your 2019 book with Henry Holt, Archaeology from Space, how the-

Future shapes are passed.

How the future shapes are passed.

That’s a twist on the timeline right there.

That’s a Marty McFly moment for those of you who are listening.

It’s your kid, Marty.

That’s your kid’s Marty.

Speaking of Back to the Future, I understand offline that you’re a big sci-fi fan.

We love sci-fi fans.

Huge sci-fi fan.

Huge.

What a note to end on.

Let me see if I can take this out with a cosmic perspective.

When you’re in school and you learn about the various sciences, no matter what course you take, there’s a book and there’s a book on that subject, and then you learn it and you do it as best you can on the final, and then you move on, often leaving the book behind or selling it on graduation.

Whereas people who are deeply curious will know and recognize that we divided the science into these categories.

Nature didn’t do that.

We did.

If you look at the cross-pollination of statistical tools, of mechanical tools, of electronic tools, of methods that overlap between one science and another, and then you realize we are all just curious children poking at what sits before us, what’s under that rock, what’s behind the tree, what’s up in space.

We are all the same species, those who ask questions and those who look up and down.

these are two directions where there are frontiers that persist.

And so I am delighted to learn that tactics, methods and tools of the archaeologist can be applied to space and vice versa.

A reminder that maybe all the branches of science are not as far apart from one another as we might think, as we are struggling through them in school.

And that is a cosmic perspective.

This has been StarTalk.

Sarah Parcak, thanks for being on.

Thank you, this has been so much fun.

Thank you, thank you.

And Chuck, always good to have you man.

Always a pleasure.

This has been StarTalk.

As always, I bid you to keep looking up.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron