Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Welcome to StarTalk. I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, and I'm also the director of New York City's Hayden...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Welcome to StarTalk.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, and I'm also the director of New York City's Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History.

And I got with me my coach, Chuck Nice.

That's right.

Chuck Nice Comic, tweeting.

Thank you, sir.

Yes, that is indeed correct.

There you go.

At Chuck Nice Comic.

Was there a Chuck Nice already taken?

Yes, it was me.

What did you?

I actually didn't like myself enough to cancel that, and so I just started a whole new one called, I'm starting all over again.

Chuck Nice Comic.

In case you didn't laugh at my tweet, just remember that it's Chuck Nice Comic.

Right, exactly.

That's how that works.

Exactly.

You're also host of a spin-off of StarTalk that we're all quite proud of.

Yes.

Playing with science.

Playing with science.

Yeah, because what happened was we had, of our guests, the portfolio of our guests, the ones that were professional athletes developed their own following, basically.

And we figured, let's spawn that.

Yes.

Into its own show.

I have spawned with professional athletes.

Never thought I'd be able to say those words.

Yes.

So, and your co-host on that is Gary.

Gary O'Reilly, who was a performer, a former professional footballer.

Footballer for the UK.

For the UK, Crystal Palace.

Very cool.

Top man.

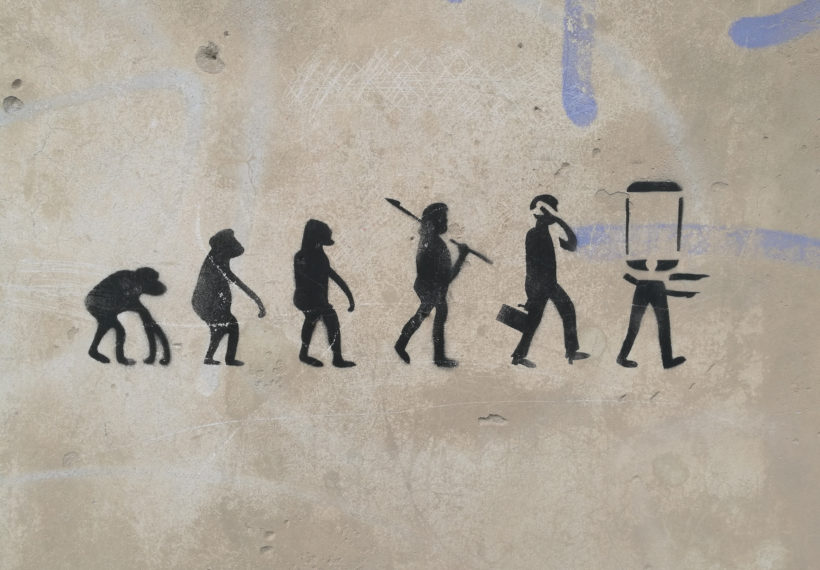

And today we're talking about the evolution of personal technology.

Wow.

Indeed.

That's a very rapid evolution.

Yes, it is.

And I'm featuring my interview with YouTube vlogger and all-around sensation in this niche.

We have Marques Brownlee.

That's a featuring my interview.

The kid?

Yes!

That kid?

Yes!

Who does all the unboxing and stuff?

Yes!

I love that kid!

Yes, and he's also known online as MKB...

There you go.

I love that kid.

There you go.

Featuring my interview with him.

Cool.

That was fun.

Just, cause I feel like, you know, okay, go to bed now and say, I passed your bed.

I feel like being his father.

But no, he's got his own world.

Like, create his own world.

He's big stuff.

Now, since I only have marginal expertise in this, generally we go out and find the real expertise as we did today.

In studio, we have science and tech writer for the New York Times and other outlets, including Wired, Clive Thompson.

Clive, good to be here, my friend.

Welcome!

Ah, it's great to be here.

So you have a book from a few years ago.

Yep, yep.

Smarter Than You Think?

Yep.

How technology is changing our minds for the better.

Yes, sir.

Wow, that is so counterintuitive.

You are the only one in the house.

I'm the only one holding down that argument.

Everybody else thinks it's making us dumber.

If you need that book, I have one for you.

Yeah, all right, all right.

None of us agree with whatever you could possibly put in there.

So in my interview with Marques Brownlee, he runs a YouTube channel, MKBHD.

Yeah.

It's a YouTube channel.

Five million subscribers, 700 million video views.

And he reviews new tech and gadgets that you might think of buying.

Or that you already bought and then you learned you shouldn't have.

So any idea what makes it so popular?

Because I'm not a first adopter, so I don't have to chase the latest unwrapping.

But see, that's what makes it so popular.

Why?

Is what you just said.

I'm not a first adopter.

He is the first adopter in your stead.

Somebody has to be.

Somebody's gotta be the first.

The first adopter.

And that's what this kid does.

And also, frankly, I mean.

I gotta stop calling him a kid.

He's a grown man.

I'm just old.

Okay, go ahead, sorry.

He's also, I think he's sort of an exemplar of what's happening, this new generation of sort of broadcasters who are growing up, not on TV, but online.

And they're really, I mean, he's really good at it.

You look at it, it's just beautifully shot.

He's just oozing charisma.

So in modern times, one perhaps shouldn't even make the distinction between being on TV or being online.

Well, yeah, in a weird way.

I mean, YouTube is such a funny old phrase, right?

Because tube, I mean, who actually watching YouTube remembers what a tube has?

None of them.

None of them, yeah.

I barely do.

It's so like, you know, I've got a couple of young kids in grade school, middle school, and for them, what they watch, where they learn things from is YouTube.

Once we got a TV box that hooked up to YouTube, it's just YouTube on TV.

Like, there's no actual TV being watched.

Well, they don't make the distinction.

That's right.

Right, right, right.

So that's an emergent fact.

I think it's beyond just not making the distinction, because I have also an 11-year-old, and he is resistant to television.

Right, yeah.

The fact that he has to do it on their time and their schedule actually-

Sit down in front of a thing attached to the wall.

It upsets him.

It's like, how dare you?

And there's also sort of, I mean, I think there's kind of an authenticity that comes, or apparent authenticity, hard to say how authentic it really is, but from seeing someone who looks maybe more like someone you might actually know doing this.

Like, my kids watch all these Minecraft videos, and it's just someone doing Minecraft, and they have a little box up in the corner showing them in their crappy little room.

That's what my son does.

There you go.

My son does.

It's how to play that game better.

That's right, yeah.

Right, right.

So YouTube feels more authentic and more, you know, like there's a real person there than a very glossy TV show.

And they get like 12 million views.

Unbelievable.

On how to execute some maneuver in that situation.

All right.

So I sat down with Marques.

So he's well known on the web, of course.

And I just asked him how he got started on YouTube.

So let's check it out.

So Marques, so apparently you've been doing this since you were three years old or something, is it?

For a while, a number of years.

More than a majority of my life.

Most of your life.

Yeah.

So more than half your life.

And how old are you now?

So I'm 22.

You're getting old.

Yeah.

Yeah.

I'll tell you how it happens later on.

It's just downhill from 22.

So you're into gadgets.

Yeah, into all kinds of tech.

I got into cameras and I got into all the tech around me.

And then this sort of merged into making videos about the tech.

And on a YouTube channel, that's a hugely popular place for people to go.

Right.

And it didn't start that way.

It started as just me making videos for like myself, just to have that exist somewhere.

And then slowly people started to discover it.

And then it sort of grew from that.

It doesn't cost money.

To review a gadget, you gotta own the gadget.

Right.

Or somehow obtain it.

Right.

So what'd you do?

I was in school.

So I was using a laptop for school.

So I reviewed the laptop and I reviewed a bunch of free software on the laptop.

And then I started reviewing paid things that I bought.

Maybe the cooler for the laptop.

That's the kind of stuff that got you off the ground.

And then you sort of proceed to check out more elaborate or extravagant things.

And then people come to depend on you.

I'm not buying it unless Marques.

When it's something you use as daily as like a smartphone, for example, that's the kind of thing you do actually put a lot of research into and watch a whole bunch of videos on before you actually buy it.

So when did you realize you started having a following?

I think one of the turning points is a video I did about a web browser when Safari by Apple came to Windows.

I made a video about that, woke up the next morning and I had a couple of thousand views from people who weren't subscribed.

That was kind of a light bulb moment, like, oh, people actually kind of care about this timely information.

And by then you had just turned five years old.

I think I was probably about 15.

So I'll give myself a pass.

I just wondered, did your parents worry about you?

If you're just playing with gadgets, he'll never amount to anything.

He's just playing with these tools.

I gotta guess yes.

I don't actually know the answer, but I would guess, yeah.

Such is always the case when a next generation defines what the future will be.

So Clive, how would you distinguish your childhood from his?

Because you started writing and you cared about the same gadgets and software that he did, but not in that era.

That's right, yeah.

I grew up in the 80s, and then when I get out of college in the 90s, there's no smartphones yet.

There's barely an internet, right?

There was a lot of these text BBSs, you know?

How Gore had to invent it first.

Yeah, absolutely, yeah.

Message boards.

Message boards, yeah, that's what it was.

Yeah, so I kinda had them.

So I could see the future coming with message boards.

I could sort of figure out what was happening, right?

But yeah, my youth is very, very different, and I think, you know.

But you would have come of age during the earliest cell phones then, correct?

Oh, you know, I was.

Mid-90s was then?

No, no, I was well into my 20s when the mobile phones came out, basically.

Did you have the shoulder-mounted one?

Exactly, yeah, the ones you can use to deflect bullets.

Yeah, I know.

It's like they're calling Mars.

Exactly, yeah.

They were.

Yeah, no, I mean, I think it was very different, and I think there's some of the things I would have liked about it.

I mean, I look at the online world now, and I think I wish I had some of this stuff.

I was in a band in high school, right?

So we make a small EP of music.

Who heard that?

No one, right?

So you wish you were born 15 years later.

Yeah, I'd say so.

That's really what you're saying.

In some respects, yes.

His band would have put the thing out on YouTube, and it ended up on Ellen.

Ellen sees it.

Ellen would have found it.

Then before you know it, it's just like, whoa, look at this.

Okay, so I try to take a cosmic view on these matters.

And I just try to imagine in 20 years, Marques Brownlee saying, gee, I wish I was born 15 years later.

Because it's something else.

What else would it be?

That would have made some next generation even more potent.

YouTube of the mind.

Of the mind, yeah.

But yeah, hard, you know, USB into the.

Exactly, you just jack in and you close your eyes.

You don't even have to close your eyes.

Right, and just sends it to wherever it's gotta be.

Right, implants it in people.

And we're looking back in these days as how archaic they were.

So I'm just curious, in terms of YouTube as a site, are there other sites now, as I understand it, Facebook is now a huge access point for videos.

I would say also Snapchat actually, or Snap as they now call it, is a really big deal.

There are, like they started this channel, it's kind of like, you know, where people do like semi-professional videos, but there's people that have just kind of blown up on Snap, I have trouble calling it Snap, on Snapchat.

That's a very, very big video area for young people now too.

YouTube is still, you know, the gorilla in the room, but there are others.

So Snapchat, the thing about Snap, right?

Crackle pop, that's what I know when I say Snap.

But Snap, the thing is that it seems like all of their technology, they're quite innovative, but it seems like all their technology just gets stolen by these other sites.

How are they gonna stay in business?

I don't know, yeah, because Facebook, basically, Instagram essentially copied everything they did, and now it turns out that Instagram's blowing up because people are doing that kind of quick viral video thing on Instagram.

I think that's a good question, I don't know.

If you don't know, give me the guy who does know.

Exactly.

Wheel him in.

So with phones coming out, the next generation of phones look pretty expensive, the next iPhone is gonna be up there.

How influential do you think those reviews are in people's buying decisions?

Oh, I think they're awfully big.

I mean, when I talk to people and ask them how, they learn about things.

Like I'll ask them and they're like, yeah, it's all YouTube, all YouTube.

Like they immediately go there to try and figure out what something looks like, what it feels like, what it works like and whether or not they should spend money on it.

So YouTube has become the conduit for learning about something before you buy it.

Absolutely.

So I asked Marques to just sort of reflect on how technology has evolved over his short number of years reviewing it.

So let's check it out.

So you're 22 now.

So in your long career as reviewer, what would you say has changed most since you were 15, let's say, or that has impressed you most for what has changed?

I'll give two things.

One, I talk about a lot of handheld electronics like smartphones, tablets, laptops.

Displays have impressed me a lot.

The quality and resolution, the crispness.

The quality, the detail, the crispiness, all that stuff a lot in the last couple of years.

And also more recently, cameras.

Cameras in smartphones, cameras in laptops, the front-facing cameras.

But especially in smartphones, we've gotten a lot better.

But the number one thing I'd say is the displays.

And the quality of displays has enabled a whole industry to land in that medium.

Isn't that correct?

Yeah.

It's not just making what you saw previously better.

Yeah.

It is opening up entire new industries.

Is that a fair statement?

Virtual reality is an example where you wouldn't have a super high-resolution display right up against your face with a lens to focus on it to put you in another world.

That would not be possible with the displays four or five years ago.

Because that close to your face, the lower resolution would be unsellable to you.

Is that a fair...

Yeah.

Okay.

So we crossed certain thresholds of device innovation.

Yeah.

Apple might use the term retina display to describe a display where the pixel density is so great that your eye cannot discern individual pixels.

Pretty much every phone has a retina display at this point where five years ago that was not the case.

And even the photos you take with the cameras getting so detailed and such high resolution that, again, the type of images you can take out of a camera on your smartphone are often better than something you get from a dedicated camera like seven, eight years ago.

Yeah.

So Clive, can you explain why this is happening?

Yeah.

I mean, it's just demand and supply, right?

So once...

No, I didn't know the demand stuff that I'm buying now.

I mean, it's like, oh my gosh, I guess that's kind of cool.

Once people start...

Once an iPhone came out and people realized that they wanted...

10 years back in...

10 years ago, right.

If an iPhone comes out and they don't want a little flip phone anymore, they want something as a screen on it, right?

So that produces an enormous demand for those screens.

And over in Asia, the factories start working and working, working, working.

The price drops dramatically.

And so the high end is always chasing more and more pixels and more resolution and greater brightness.

But even that has dropped and dropped and dropped and dropped to the point where like, you know, it's an expensive part of the phone, but it's amazing how cheap you can get really nice screens now over in Asia.

So I now have a nice screen.

But like I said, this, I never would have imagined using my cell phone saying, gee, I want to take a picture with my cell phone.

This was not an urge.

Yeah, that's right.

I don't think anybody had that urge.

No, no.

I think what might have driven that.

In fact, I thought they were forcing it on me.

Initially.

They were.

If you remember.

And I think what did it was, believe it or not, apps.

The advent of apps and these photo apps that allowed you to do your own little like photoshopping and to manipulate images and then post them.

It's like.

Yeah.

I mean, I think in many ways, the tipping point was probably Instagram, right?

So that was the first thing where you could take a picture and you could put a filter on it and make it look prettier than what you did.

Right?

And this was an intentional thing that Kevin Systrom, the guy that invented it, was talking about with his girlfriend when he was designing it about sharing photos.

And she said to him, they were talking about it.

And she was like, the problem is I don't want to share my photos.

They don't look as good as yours.

He's a big analog camera guy.

And he said, well, that's because I'm using all these films that produce these lovely filtering effects.

He said, well, you need to put some filters in that thing.

Lo and behold, that's exactly what worked because you could take pictures, make them look pretty, instantly share them.

That took off.

Are we going to go up against, is there some Moore's law of personal technology?

Yeah, there is.

And is that going to end?

Is that going to level off?

Well, first of all, guys, let me just say that there are some people who may not be familiar with what Moore's law is.

I mean, I know what it is.

Other people might not know it.

You know, those other people as they may not.

But what is Moore's law?

In brief, Moore's law is the observation several decades ago that computer chips were getting basically twice as fast every 18 months.

And that's because they could make the components smaller and smaller and smaller.

They are now at the atomic level.

Those wires are so tiny, you can't make them any smaller.

That is what's called the end of Moore's law.

So will the devices stop getting faster?

And this is Gordon Moore.

Gordon Moore, that's right.

Yeah.

One of the founders of Hewlett-Packard, I think, is that correct?

Yeah.

Oh, boy.

You're putting me on the spot here.

Was it either that or...

Mr.

Tech journalist.

Or Fairchild semiconductor.

Anyway, the point being that the question is, you know...

But you know the issue.

When the wires are so small and they reach atomic distances, then quantum effects between wires start taking over.

Sweet.

It is sweet.

That is awesome.

So the wire is pretty big.

No one will know that it's independent of the wires sitting next to it.

Absolutely.

Because the wave function talks to them both.

Dude, that's amazing.

I love it.

Look at physics.

So, yeah, so they're essentially having to figure out how to make things faster without making them smaller.

Okay.

So, fine.

So even if you do level off at Moore's Law, are there...

Fine.

But presumably design can change.

Other limits?

Price?

Design?

At the moment, actually, weirdly, one of the big limits is how fast can you get data to that device from like a cell phone tower, right?

That's almost a bigger limit now than the speed of the phone.

It's like cable TV.

That's right.

You know what I mean?

They talk about how great your cable is and we have this fiber optic and whatever and I was like, yeah, I still got copper running into my house.

Who gives a damn?

I actually fell for that crap and I was just like, this is the exact same cable I had before.

So can we think of these smartphones as augmenting our human physiology?

Absolutely.

Sure.

I mean, every technology we've had has to a certain extent, as Marshall McLuhan put it, been an extension of man, right?

So TV extended our vision, the phone extended our ability to speak and talk.

These things are the strongest extensions of humanity that we've ever had.

And I would say that you could think of them as almost like a sense apparatus.

They're like a form of ESP by which we tap into what people are-

Yeah, not ESPN.

Exactly.

But a form of ESP.

Yeah, that you could think of them as a form of ESP by which we sense what other people are thinking and talking about and doing like all the time for good and for ill, right?

Because on the one hand, wow, you learn a lot of great things.

On the other hand, it's almost like having telepathy and being unable to shut other people's voices off in your head.

In fact, when I tweet and I look at the responses to that too, I usually tweet something educational.

That's my intent.

And I try to add a little funny in it.

If I can't, just a little, you know, to bar from it.

Yeah, I'm gonna blow smoke.

I get B plus.

I get B plus.

I get B plus.

Okay.

So I look at the response to it and that informed, I see that as a neurosynaptic snapshot of the instantaneous reaction to words I use, to phrases I compose, to ideas I put out there.

And then when I give a public talk, I fold those in and I'm way better communicator.

Sure.

So that's my ESP in a sense.

Yeah.

That's right.

Getting inside the head of a million people.

I just figured out I'm doing Twitter all wrong.

Well, so coming up more of my interview with Marques and it's all in his capacity to tell us what's going down in the technology spectrum.

We're back on StarTalk, I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, co-host Chuck Nice, in-studio guest today, Clive Thompson, a tech writer for The New York Times and Wired and other venues.

A few others, yeah.

A few others.

We feature my interview with Marques Brownlee.

He's a 20-something, early 20s, reviewer of tech devices that you might think of getting.

He does this on the internet, has millions of followers.

And so I got here sort of an interesting sort of perspective, okay, on what role these portable technologies might play today.

So I just had to ask him what that relationship was between these technologies and our lives.

Let's check it out.

You've only really ever known the internet as a thing in your life, rather than having to have transitioned from walking to the library to get information and data.

So to you, your life is practically defined, enabled by information you get on the internet, what those apps do for you as you conduct your life.

So there's a certain amount of trust that you place in this information, in the integrity of this information.

Yeah, I have an app on my phone called Google Now, and if I go to class enough times with my phone in my pocket, it knows that I go there every day, so it puts that down as where I work, but it knows I go there every day.

And if it's far enough away that I drive there every day, it'll start to show me a card in the morning of when I should leave based on traffic to get there on time, because I go there at the same time every day.

So now it's helping me get there on time because it knows where I go every day.

If there's an accident, it'll wake me up earlier to tell me you should head out earlier.

Because there's an accident on the road there.

Because there's an accident on the road you're about to take to get to the place you're about to go.

I'm okay with all of it because it's helping me.

If people don't like to think that Google knows all this about us, they're gonna use this information, or even the machines that are collecting the information can turn and use it.

I feel like if they're giving back this information to help me in this way, that's actually really useful.

I'm okay with it.

So I'm a senior citizen among the three of us.

In my day, privacy was paramount.

Absolutely.

And I don't know that this next generation gives a rat's ass about privacy.

Not at all.

All their stuff is on internet, you know, their height, their weight, their sexual preference, their gender pronoun, and can you just offer some reflections on the meaning of privacy in the era of quote, helpful apps.

Helpful apps.

I mean, it's definitely changed a lot for exactly the reasons we've been talking about.

It is sort of impossible if you're young right now to have a social life without participating in, you know, all these apps.

You know, if you're-

Social apps.

Social apps, exactly.

Like whether that's Snapchat or Facebook or whatever, you're kind of off the grid.

And there are abstainers, it's kind of funny.

You will find young people who are like, I will have no truck with this.

But they're the ones who are like kind of the iconoclasts who don't really care about, you know, about having, you know, a big group of friends.

So I think one of the problems young people have is that like they're, it's not even necessarily that they have a fundamentally different attitude towards privacy, but they have no choice but to do these types of things in the same way that maybe for us when we were younger, you know, not getting a driver's license was sort of basically a vow of I'm never going anywhere that the cool kids are going, right?

You know, you could have said, hey, I think-

I grew up in New York City.

Yeah, okay, I grew up in suburban Toronto.

So you needed to drive, yeah.

And so, you know, if you, back then, if you opted out from that technology, you had a real social trouble, right?

So these are cultural social forces operating.

Absolutely.

And if you're in the middle of it, you don't even know that there was another option.

Yep.

But my problem is that you heard in his statement was resident a certain amount of trust in the responsibility that Google has for all this.

Yeah, he's trusting these companies.

He was very trusting.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Do you trust, what's your trust level?

Wow.

I don't trust anybody.

That's what I'm saying.

No, not in a conspiracy way.

I don't want you knowin this about me.

Because it's power and we all know power corrupts.

That's what I'm saying.

Knowledge about you is power over you.

See, you know, Franklin Ford is like old people under the bridge.

I was about to say, let me tell you something.

The only way this coulda got worse.

Here's Google, okay, especially in the black community, here's Google if it had been invented 25 years ago.

Google in the black community.

Why don't you mind your damn business?

That's basically, that's the response, but go ahead.

So Franklin Ford just came up with a book.

He talks about big tech, right?

And he means the great, big, huge companies that have massive amounts of power, you know, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, and Google.

And he makes a distinction between that and like kind of smaller tech, which are companies that you might actually know and trust.

And I think that's a good distinction because you know, what you guys are worried about.

No, but all those big ones used to be little.

Don't tell me that.

No, no, no, no, I can just be.

They're just big now.

I agree, but like, so the problem we have.

They were born big.

The problem we have, but there's small tech you can completely trust.

Like, you know, open source stuff like the Tor Project, right?

So their whole point is to try and make it easier for you to have privacy online.

And it's open source and it's like a run for nonprofit, civic-minded hackers.

There is technology out there that you can trust.

It's not the stuff that is big and is rewarded heavily by the market.

By commercial entities.

It's all about the commercial entities and advertising.

Is there anything out there that you've said, all right, that crosses the line?

Oh, yeah, sure.

I'll give you an example.

Like, so there was, I came home from a summer vacation and I opened up my Android phone and Google said, hey, you know, we just put together a slideshow of photos and like points on a map of all that I'd done the last two weeks, just because we thought you might like it.

It was so creepy, right?

It was super creepy.

And I always turn my locations off, okay?

But sometimes you forget and I got that same dog on slideshow and it freaked me out.

It doesn't matter, I'll tell you why.

Why?

I'll tell you why.

As I understand it, okay?

Can't Google now, if you put your picture up in the cloud, it can do an image recognition of your surroundings, compare it with all of their sound like, and say, oh, was this in the plaza de piazza of the, and shall we ID it that way?

Absolutely.

In fact, actually, if you ask me.

You said it like, of course.

If you ask me for the technology right now that most unsettles me, it's the galloping rollout of face recognition technology into everything.

Into everything.

And so I'm like, I don't want my microwave recognizing my face.

I don't want omnipresent face recognition all over the place, but it's getting so easy to do.

I mean, just the other day, Google helpfully said, hey guys, we just made TensorFlow, our AI framework, so it can run on basically a Raspberry Pi.

Yeah, that's crazy.

That's insane, by the way.

And let me tell you something else.

Here's what really scares me about the facial recognition.

Aside from the fact that, like you said, I don't want my microwave recognizing my face, is the fact that once somebody learns how to hack that and make my face like face off, okay, now they can just walk around and be me.

However, as I understand it, it's not just, it's better than what you would think, it's better than how you would do thinking that you're looking at yourself.

Because it's actually measuring ratios of dimensions of your face that are extremely hard to duplicate.

Oh no, I'm not talking about the, I'm talking about going beyond the actual facial recognition where that I go in and tell the software that, so I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

I hack it and say, so now everywhere Neil deGrasse Tyson, where everywhere I go, I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

I've hacked into it.

You know what I'm saying?

That's what's scary.

That won't happen.

And that's going to happen.

This brings us to, because you can't out program it, you can just hack it in the back end.

Always go around.

So this brings me to the concept of internet identity.

Who are you on the internet and how privacy breaches this sort of thing?

And so I had to ask him, Marques Brownlee, just is the internet not only helping us but now defining us, defining our identities and what it's gonna do.

Let's check out the interview.

So is your life being defined by all the ways the internet inserts its way into your routine?

Because in my generation, it's still this, it's a luxury, it's a convenience, it's a tool.

It is not me.

Has it become you?

So I would say yes.

I would say the internet is part of our life and always has been in a way that other generations exist alongside the internet and may go over and use it once in a while.

Everything we do now, whether it's communication or sharing anything with anyone, whether it's someone I know or just posting something for the world, all of it goes through the internet.

The convenience stuff, like I said, where a normal going-to-work routine would have no internet involved in it in 1990.

Today, it's relying upon Google Maps and my alarm clock on my phone and everything telling me when to wake up and when to leave and how to get there.

So, in that way, I do think we are completely tuned into the internet in a way that's not the same as any other generation, yeah.

But can I say, it's not that so much you're tuned into the internet, the internet's tuned into you.

That also is true.

Do you have an identity outside of how you are represented on the internet?

You've got a Facebook page, this is what I am, this is how I want the world to see?

It's almost like a pair of identities where you have your social life, but you have your social media life, as well, and sometimes they're different.

You'd be surprised how different they are with a single person having an online life versus an offline life, which is kind of weird.

Okay, how close are the two for you?

For me, I'm the same person.

We'll be the judge.

You can look it up.

I'm out there, it's all the same.

So I wonder if, one of my favorite comics from the 1990s New Yorker, there's a dog at the computer.

You know what I'm talking about.

And he says to the dog next to him, good thing about the internet, no one knows you're a dog.

That's pretty awesome.

So what does it mean and how real is it for people to just have a dual identity?

The internet identity and then their actual selves.

Well, I'll bite that off first.

I mean, we've always had multiple identities.

In fact, you know, in the early 20th century, in the late 19th century, you had a migration of people from small towns to cities.

And one of the things I loved about it was in the small town, everyone knew your business and it was sort of impossible to reinvent yourself or to discover other sides of yourself.

Because everyone's like, no, that's not who you really are.

I know who you are, Clive Thompson, right?

You go to the big city and suddenly it was like, lo and behold, wow, I could be someone different.

Or I could be a couple of different people.

I'm one person at work and then I go off and I do my thing with my crab.

Just a quick thing, there are people who say, the city is so crowded.

I wanna go out into a rural, suburban area where no one will know me.

Yeah.

No, it's the opposite.

They will figure you out in 15 minutes.

Yes, yes, whereas in a city, no one gives a...

Right, there are too many people to care.

Nobody cares to know you.

Yeah, right, right.

So I think having multiple identities is actually healthy and a good thing, frankly.

You just said, repeat that.

I think having multiple identities, as long as they're not sociopathic and you have like a different postal box where you sort of order.

For a moment, I thought I was getting approval.

All right, so anyway, that's healthy and there's an extent to which I think you see people trying to do that online and kind of failing because large corporations don't want you to have that.

They want to know everything about you.

They want to assemble it all in one place so they can target ads at you.

This is Mark Zuckerberg's original statement of Facebook, having different selves is a sign of inauthenticity.

And of course he's gonna say that because he wants to have everything about you so he can target ads at you.

But where he's, I was about to say failing miserably, but then I thought this is who I am and I'm saying that he's failing so that doesn't make sense.

But I think what he's not taking into account is the fact that when you do have your different selves, they can also be authentic.

Sure, absolutely.

You can have different cells that are authentic cells.

That's my point.

So I play in bands and I'm a journalist.

Often those two crowds have no idea about the other part of me, right?

Like when I go and hang with musicians, some of them don't read the stuff I do, they're just, that's Clive the guitar player, right?

Exactly.

So ultimately are there legal ramifications to access to your private information?

Well, I mean, that's a good question.

I'm not a lawyer.

And by the way, who reads the, you know?

Yeah, the disclaimer, the legal disclaimer that when you, and I always thought that when you click yes, I agree, that some type of really weird things should happen.

Like you hear a knock on the door and somebody's like, yeah, we're here for your wife.

And you're like, what?

Yeah, man, when you clicked I agree.

Oh, and it's crazy stuff.

The, I mean, so I'm not a lawyer, so I'm not gonna give you a good legal answer, but it's definitely true that I think one of the big issues right now is like, you know, what protections, legal protections do we have for the way our data is used, right?

Now over in Europe, they actually have a much different view.

Germany particularly, because they have the Stasi, right?

So they have a lot of laws and Google runs against these and hates them and lobbies against them.

You know, I think we probably need much, much better protections in this country.

Can and should an employer hold your social media life against you?

I don't think they should, no.

I really don't think they should most of the time, particularly at the hiring level, right?

That's what I'm talking about.

Yeah, sure, at the level of hiring, okay.

And then they say, what are they posted and what drunken pictures, you know?

I don't think they should be doing that stuff because that's tantamount to, in the pre-internet era, say, hey, can we come home and just rummage around your house?

You know, and that was considered unreasonable back then.

It should be similarly considered unreasonable now.

That's why I'm a comedian today, because all my stuff on social media, I can't get a job.

So you just tell jokes about it.

Exactly.

We gotta take a break, but coming up more on the future of technology, StarTalk for 10 minutes.

We're back on StarTalk, and I've got my expert guest, Wired magazine and New York Times columnist, Clive Thompson.

We're talking about the future of technology, Chuck Nice.

That's right, sir.

So we're not experts at this, but we have strong opinions on it.

Yes.

And he's got expertise, so we're good.

And we're featuring my interview with Marques Brownlee.

He's the 20-something year old who's been reviewing technology for everybody on the internet.

So I had to ask him, where does he think technology is headed?

Let's check it out.

So what are you gonna be telling your kids?

And you say, back in my day, when I was 22, look what we had to do.

Oh my gosh, can I have sympathy, please?

Honestly, I'm thinking cars.

I'm hoping cars.

How we drive cars today and we...

No, those would be really big gadgets.

Does that count as something you would review?

I count that.

I say anything with an on button is game.

Technically, not every car has an on button, but if you look at some of the more high-end cars today, they've got electric systems galore, plenty of high tech.

I feel like a lot of the stuff we have now that's inside of a car that you have to control, like the steering wheel, even if you're in a self-driving car, they still want you at the controls in case something might go wrong because it's a computer and it's a system that could go wrong.

That's funny because that, the fact that you say that implies that something would go wrong with the machine that the human can correct.

Rather than something going wrong with the human that the machine needs to correct.

Yeah.

Because last I checked, all those accidents on the street are humans messing up.

For sure.

But even the system's getting to the point where everyone has a car that is capable of driving itself.

No one even needs that space of a steering wheel in the car.

You just kind of sit down.

It's maybe a bench facing another bench and you just kind of ride along to your destination.

I feel like that's way down the road where we're at the point where a car is sort of fusing into the next generation of vehicle at this point.

So if cars do all the driving on the road, then in principle, you can up the speed limit.

Right?

Because you're not at risk of reaction time.

Exactly.

So I'm imagining you go 150, 200 miles an hour driving down the road.

No problem.

And they'll just weave seamlessly within each other in a way that would be scary if a human was trying to do it.

But it'll just be totally normal.

That's right, because if all the cars are going 200, any high speed, then it's a moving coordinate system so that a car can move in and out of that.

That's the other thing.

All the cars are sort of talking to each other as points in the matrix.

And they can all sort of avoid each other, because they already know if a car all the way on the right lane with a bunch of stuff in between it knows it wants to go to the left, and car all the way on the left knows it wants to go to the right, and they can tell the cars around it, I'm trying to go to the right, I'm trying to go to the left.

Human couldn't do that with another car on the other side of the road.

No, you can't honk.

And then you can try, you can try, but those machines can work with each other much more efficiently.

I never considered that.

So it's a ballet on the freeway.

It's a symphony.

Symphony.

It's beautiful.

It's beautiful.

That's really beautiful.

So Clive, why do we get software updates?

Because there are bugs that are found by the many users that often the testing is just, let's put it out there and see what comes back.

Right?

So self-driving cars where lives are at risk, what is the risk of there being some kind of bug where it kills people?

Or on top of that, what's the risk of hacking into a car to create the accident in the first place?

I think the hacking might be a bigger risk than the bugs.

I mean, regulatorily, it's going to be tricky for them to get those cars on the road, because cars are pretty tightly regulated unless they can demonstrate, you know, pretty persuasively, there's not a lot of bugs.

Now, hacking is a different thing, because now you've got a human person trying actively to break something, right?

And that's a much more volatile risk.

There's already been situations where cars are out there, and, you know, Wired hired a couple of hackers to literally take over a car while it's going on the highway, and they did it, no problem.

Yes, they did.

So I think, I've driven in self-driving cars.

It's the diabolical division of Wired here.

Exactly, yeah, yeah.

No, I've ridden in Google's self-driving cars.

Felt pretty comfortable.

They're actually, in a weird way, they're almost sort of cautious drivers.

It's like being there with your grandmother at the wheel.

Right now, could get faster, as you point out, but overall, you know, if I were to compare it to the dangers of humans driving cars, I'm probably okay, you know, with the self-driving cars if it's well regulated.

That's the big if, right?

So that's the future?

I think so, yeah.

I mean, I think it might be, it might take longer than we think.

You're getting these rosy predictions of five years.

Yeah, I don't see five years.

No, no.

But the fact is that they are on the road right now.

They do work.

I forget the trucking company.

Auto.

Auto.

So now, Auto has gone cross-country, traversed the country several times with their semi, and the only thing the human being is doing is monitoring.

They have a guy that sits there and monitors.

That's it.

And you could also, I mean, frankly, the reason I'm kind of in favor of it is it has potentially great environmental benefits, right?

Because you get way less idling, you get way less jackrabbit starts.

These are the things that burn huge amounts of CO2.

What's a jackrabbit start?

You know, when you're at rest and you suddenly burst off, right?

Because humans want to accelerate fast.

Robot cars are like, no, I'm just gonna ease forward.

Boy humans, testosterone-infused boy humans.

There's that, yeah.

I didn't learn how to drive until I was 25.

And that's after the boy human testosterone forces have dissipated.

Oh, nicely done.

Yeah, yeah, it was very, and you get lower insurance.

All boys should not be able to do anything until they're 25.

That's exactly right.

We're three men sitting here, we know the deal.

We know, right, right.

If you're under 25 and you have a penis, you're effing crazy.

That's all there is to it, okay?

There's something deeply wrong with you, you need help.

You should talk to somebody.

Every one of you, okay?

So what intrigues me is when you have a self-driving car and it's talking to other cars, there's signals, I just learned that the Tesla talks to other Teslas.

So if you come onto a bumpy road and then you make the adjustment to change your suspension, which of course you can do, that information goes to the next Tesla, any other Tesla that will be on that road and it'll pre-adjust the suspension before it enters the bumpy part of the road.

See, this is where the stuff just gets creepy, man.

This is what I'm talking about.

Don't you want your car to know?

I don't want my car talking to no other cars.

Do not talk to any other cars.

How many times do I have to tell you?

Don't talk to strangers' car, okay?

Stranger danger.

I don't want that Tesla just like...

Don't you want to know if there's a hazard in the road?

No, what I don't want is that other Tesla saying, you know your owner doesn't love you.

And the interesting point's gonna be, will there come a point when the government decides that the self-driving cars are so much safer that it's illegal for a human to drive a car?

They could surely do that.

However, I've thought about this.

Yeah.

It's not, you cannot take a horse on the interstate.

Right.

Even though there's a day when horses were the only things that brought you around.

Good point, good point.

So now, if you like horses, you go to a stables.

So there's a place for you to...

Exactly.

So we'll have racetracks.

We'll have racetracks.

Where then, if you're still a sports car collector, and you want to control your own car, you take it to the sports...

You have a berth at the sports track, at the driving track, and that's where you drive, and you get your thrills, just like the horseback riders do.

So the Mustang will just be just like a real Mustang.

You gotta go to the ranch.

You gotta go to the stables, and pull your Mustang out of the garage, and take it for a ride.

Giddy up.

Oh man.

I asked Marques, is there any other future of technology that he's excited about or intrigued by?

Let's check it out.

When you're the ripe old age of 32, how do you want to be living life?

What technology do you want to be surrounding you?

Well, I'm 10 years from now.

Let's see.

I hope car tech is on another level.

I hope that's the most exciting part.

That's the right horizon for this to kick in, if it's gonna do it.

All right.

I hope the handheld devices we have are no longer handheld.

And that's pretty ambitious for 10 years, I think.

But communication.

Well, someone would argue they're like in your arm or like attached.

You've seen wearable tech smartwatches, they kind of shrink down and end up on your wrist or on your ear or on your neck or something like that.

But how about the biology technology interface?

Interfusion.

Put a little USB thing right here.

Yeah, right in your neck.

They kind of did that and no one called it that, but they were USB ponytails in Avatar.

Remember that?

They take their hair and they plug it into the plant.

Yeah, yeah, and they would communicate with one another.

Yeah, that's the kind of thing I see, though, is like a much more portable but complete version of your digital self to just exist and be able to move around.

So Clive, how real is this interface of biology and technology?

And I ask because do I need my iPhone neurologically attached to me when it's sitting at my fingertips to begin with?

I mean, isn't that the same thing?

It's awfully intimate right now, right?

It's right there.

Completely.

Yeah, they talk about wearable technology.

We already have wearable technology.

We're all carrying phones with us, right?

It's in my pocket.

But there's people working, Google's working on these contact lenses that have display technology in them.

They're working on that quite seriously.

So any ethical frontiers here that we don't know about yet?

Bioethical?

I mean, the bioethical frontiers' concerns are always, do you produce something that's great for intelligence, performance, and ability, but is so expensive that only rich people get it, right?

That tends to be the answer.

The answer is yes.

No, I heard a rebuttal to that from Ray Kurzweil, because we had him on StarTalk.

Sure, yeah.

He said, no, that's not a problem.

The haves and the haves not.

And I said, why?

He said, because when it first comes out, it never works well anyway, and it's stupendously expensive, and it's not, and so yes, only a few people have it, but only when it becomes mass market does it become truly functional.

No, he's right.

He's right.

When phones first came out, you know, you had to be pretty rich to get a phone.

The first computers are pretty useless.

First computers.

They're useless, and the first phones are completely useless.

And the ones that are mass market are the ones that are most, so that's why I don't see that as a problem.

Well, I mean, I hope he's right, shall we say.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

So, Clive, some great, haven't you?

Yeah, it's been great being on.

Good conversation, guys.

We gotta bring you back.

We'll surely find some other excuse.

Yeah, you're much better than the other writers.

Well, cool.

Chuck, any final thoughts here?

No, I just think that this is a very scary time if you're somebody.

I meant happy thoughts.

Technology is wonderful, and I'm so happy that we have it, yes.

And I think the human race is so much better off now that we all have our faces stuck in some stupid phone instead of talking to one another.

You know, I think we are still in our infancy.

Do you know, it took multiple centuries after the printing press before anyone figured out that you could make something called a newspaper?

True.

So, you had broadsheets and things, but a routinely produced newspaper?

A daily.

A daily.

That took like 400 years, 300-something years.

So, here we are at the dawn of the internet, even though it's 10, 15, 20 years old.

I think we don't yet know, we're still playing with ourselves, right?

And I don't think we have, I think there's a level of maturity of how to use the power of this technology that we have yet to attain.

I just love that you said level of maturity after you said playing with yourself, and I'm sitting here like, I can't help it!

By the way, the number one thing that the internet causes.

People playing with themselves.

So I just think there's a level of technological maturity that we have yet to achieve.

And I don't know when.

Is it 50 years, is it 100 years, 150 years?

I don't know, but only then can we really say that it doesn't own us, we own it.

Nice.

You've been watching and probably more likely listening to StarTalk, and I've been your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

Chuck, thanks for being here.

Always a pleasure.

Clive, good to have you.

And I publicly thank Marques Brownlee for agreeing to that interview.

And until next time, as always, I bid you to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron