Join your cosmic tour guide, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, as we explore your favorite episodes from Season 4: StarTalk Live at Town Hall with Buzz Aldrin (Part 1), StarTalk Live! Satisfying our Curiosity about Mars, StarTalk Live! Exploring Our Funky Solar System, The Joe Rogan Experience and Eureka! Asteroid Mining. Celebrate science with our out-of-this-world guests, from Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin, the second man to walk on the Moon, to Dr. David Grinspoon, a planetary scientist exploring Mars via the Curiosity Rover, to Peter Diamandis, the man who wants to mine the asteroid belt. Laugh along with comedians John Oliver, Sarah Silverman, Jim Gaffigan and our comic co-hosts, Eugene Mirman and Chuck Nice. Season 4 was our most listened to season ever, so there’s no way we could fit all of your favorites into a single episode – but you’ll have to wait until January 5th for Part 2 when our Time Capsule concludes with your favorite Cosmic Queries.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

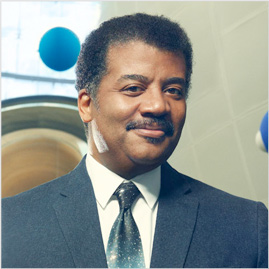

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Welcome to StarTalk Radio, I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson. For my day job, I'm an astrophysicist and director of New York...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Welcome to StarTalk Radio, I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

For my day job, I'm an astrophysicist and director of New York City's Hayden Planetarium, right here in New York City, part of the American Museum of Natural History.

The show you're about to hear is a time capsule, representing fan favorites from the fourth season of StarTalk.

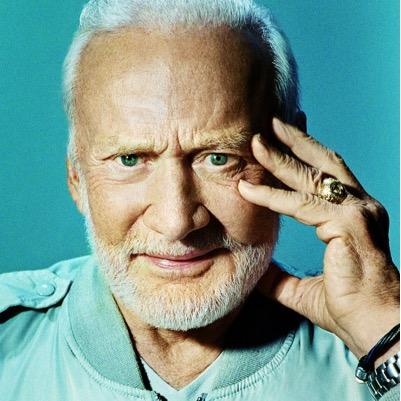

We start off with the number one pick, our live show at Town Hall in Times Square, featuring one of the first men to walk on the moon, Buzz Aldrin.

Also appearing in this show was the author of A Man in the Moon, Andy Shekin, and comedians Eugene Merman and John Oliver from The Daily Show.

Buzz, were any of you guys thinking we're doing this to explore, for science, for anything other than flexing muscle?

Of course, yeah, we were doing it for that reason, but it was certainly a race.

We were told that.

I probably was more antagonistic than anybody else.

There were a couple of, you know, real cozy people.

Let's buddy buddy.

But those were our enemies.

Were you hoping you'd get to the moon and there'd be a rush on that you could punch there?

You're on the moon, you're collecting rocks, so there's a little bit of science that comes out of that.

You lay down the corner reflectors, right?

Those are cool.

Corner reflectors.

Yeah, that was Neil's experiment.

It was pretty easy.

You just put it down.

That's all you had to do, put it down like that.

The seismometer was a hell of a lot more complicated.

And you deployed the seismometer?

Yeah.

There was a leveling device that consisted of kind of a round dish and they had a BB in there.

Okay, now with the low lunar gravity, guess what that BB was doing?

Come back an hour later and it's right in the center.

That's not a bubble.

It sounds like a child's toy.

I've been a scuba diver since 1957.

And so when these two engineers from Baltimore decided that maybe this stuff in space could be done in another medium, like underwater, neutrally buoyant, where the body weighs about how much percentage are we, 90% water?

You get the same density as water and you're bubbling.

So anyway, it sounded pretty good to me.

Some of the other astronauts said, no, no, no, that's just not going to work.

But it did.

So Buzz, you've been a scuba diver and an astronaut.

Do you just hate the surface of the Earth?

John, but there's more.

Not only does he hate the surface, even when he's on the surface of the Earth, back in his day, he was a pole vaulter.

Do I not have this right?

God, I would get away from the ground.

So you started with pole vaulting and then were like, So Dennis Tito, who is a gazillionaire in California, who was the first space tourist, he flew to the...

Just bought a seat on the Russian Soyuz.

Right, in 2001.

And how do the old-timers feel about people just buying a seat?

When you guys were starving in the desert, becoming the right stuff to earn that seat, you got people who would just pull out a billfold and plunk it down.

You okay with that?

No, I'm looking at how much I got paid for going to the Burk.

How much?

I filed a travel voucher when I came back.

You had to expense going to the Burk.

At the heart of the Cold War.

Is that true?

Most of the meals were government meals.

Most of the transportation was government transport.

The rocket, the parachute, the aircraft carrier.

I did need to rent a car to get from the airport in Florida to the crew quarters.

Did the government cover that, or were they like, sorry, you have to get there somehow and then we'll bring you to the mood part?

Look, I have a damn official government travel voucher, $33.31.

That was a lot more in 1969.

Fair point.

You did all right, you're welcome.

You could buy the Rolling Stones' catalog at the time.

You know, I happen to be an Axe ambassador.

You know what that is?

The stuff they spray on your body?

The stuff that makes you red.

See, Buzz, I would have thought at the bar telling the lady, I went to the moon, that that would be enough.

You know, you don't need something to smell.

You are the one man who does not need Axe body spray, Buzz.

We need that, to smell like our concept of what you smell like, yeah.

Presumably the moon has a special place in your heart and mind and soul.

So there's no talk today about moon bases.

You're okay with that?

Oh, I'm talking about moon bases.

You are?

Yeah.

You want moon bases?

No, yeah, but they're for international people, not the US.

Oh.

We'll build them.

Yeah, sure.

He's a Ruskie.

So you've got...

Not anymore.

No, not going to happen.

So moon bases for international science research, such as what goes on in Antarctica, I guess.

Well, it's true.

Tachenoids, Chinese tachonauts, German astronauts, Indian, Japanese.

Isn't that kind of what the space station...

But they're doing things for prestige in their country.

In their country.

That's for sure.

All of them.

We've done that.

So what should we do for prestige once again?

Lead what happens at the moon without wasting money.

Okay, so, wasting money.

When you could use it, better going elsewhere.

Like San Francisco.

You have to go.

It's wonderful.

But Buzz, if we're going to go to Mars and hang out, shouldn't we practice hanging out on the moon?

No.

Why?

Well, because the gravity is different.

So?

So.

It's got gravity at all.

Yeah, but you don't practice at one place to then go somewhere else.

Oh yeah, Mr.

Swimming Pole.

No, we didn't do that.

Please don't fly a jet into me, you are probably right.

Welcome back to StarTalk Radio, I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

This time capsule features your favorite episodes from season four.

Next up, our live show at the Bell House in Brooklyn with planetary scientist David Grinspoon talking about the Mars Curiosity Rover.

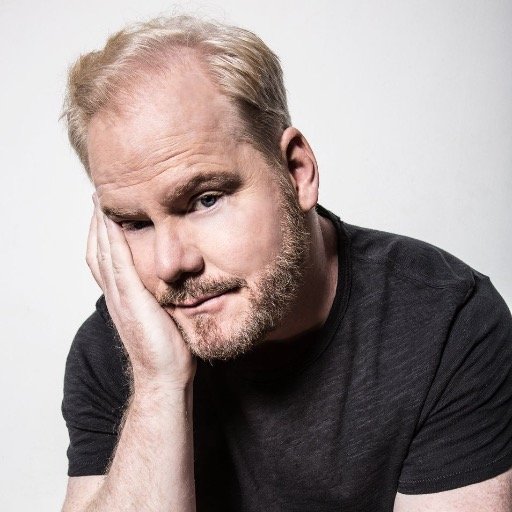

Joining us were the comedians Eugene Merman, Jim Gaffigan, and the one and only Sarah Silverman.

It was page one story.

An SUV sized rover was plunked down on Mars.

Like, what's up with that?

Well, we're really glad it made it.

Yeah, I was scared.

I said, this is not gonna work.

Yeah.

Because you go nine months and then it wasn't just the airbags like the old ones did, right?

That was scary, but I got accustomed to the airbag landing.

This one, it had like heat shields and then a hypersonic drogue chute and then retro rockets and then a hoist crank.

It was something Rube Goldberg would have designed.

And I'm thinking, I don't want Rube Goldberg on Mars.

So.

Yeah, well, this is okay videos.

Let's make that T-shirt.

Why does it have to be an SUV?

I mean, I wish they would do something a little better for the environment, you know?

Well, the last one was a Mini Cooper.

Electric.

Well, the last one was solar.

This one's got nukes.

Yeah, those stuff.

So first of all, how confident were you that this whole sequence of landing devices would have worked?

I wasn't confident at all.

I was shitting bricks.

The thing is, I'm on the science side of this thing.

So we've got our instruments.

We want to get them onto the surface of Mars and go to interesting places so we can learn things.

And the engineering side of it, those guys tell us, don't worry, this will work.

And then we say, so how are you going to do it?

And they describe this thing, you know, it's going to come in at hypersonic velocity and make these S turns and then drop off the heat shield and there's a parachute and it's going to fire these rockets and then it's going to stop 50 meters up and hover and drop things down on this.

On a hoist.

And we're like, you got to be kidding me, that's not going to work.

And it was scary.

We were scared.

I was not confident at all.

Did you know that I had a private Twitter conversation with the rover just before it landed?

What do you mean?

I don't think it was a rover.

Excuse me, I had a relationship.

Meaning you tweeted the rover and the rover was like, hi Neil.

The rover tweeted that.

You know what, it was probably just some old guy pretending to be the one.

I was like, can't talk now, I'm about to go through seven minutes of terror.

76 rockets have to fire in weird directions.

You were mentioning this tension between the scientists and engineers.

One of my last two questions was, who do you like better, scientists or engineers?

You asked the rover this.

I asked this of the rover.

And what did she say?

Yeah, it's a she, it's a she actually.

Sure it is.

Scientists have to build a lady and send it to Mars.

That's how they fall in love.

She said she would not pick between the two, that they are both important to her life.

She loves us both.

She loves us both, yes.

So it worked, it landed.

Nothing went wrong?

Almost nothing went wrong.

What went wrong?

Well, Helicopter crashed into the wall.

No, actually it was.

Martians.

It was remarkably free of glitches.

Actually, I did, my very last question to Curiosity, which is her name, was what?

She sounds very curious.

What's your favorite?

So I asked her.

So I said, I said, You typed to her, you didn't.

I have an eight-year-old son named Josh, he's my world.

Do you want to have a party?

So I said, suppose a Martian crawls out from under a rock, climbs on your back and rides you like a rodeo bull.

She said, that was not in my briefings.

I last counted, it was like 10 experiments on this thing.

What's your favorite among them?

Well, I'm a little bit partial because I'm part of one of the instrument teams.

I help propose and design and-

So by partial, you mean you're biased?

I'm biased.

Okay, so which one is-

I mean, the obvious thing to say is the cameras because the cameras are so cool because we all want to see and it's beautiful and it's amazing and part of it's just sightseeing.

But our instrument is called RAD and it is RAD.

It's the radiation assessment detector and we are measuring for the first time.

So that would RAD stand for.

It is what it stands for.

I invented that 10 years ago, sorry to tell you.

No, we're measuring how much radiation there is on the surface of Mars which has never been measured before and it's one of the things that would possibly kill you and possibly kill Martian bugs.

So we want to characterize it and see what it's doing in the soil and in the atmosphere and so forth.

So that's not measuring anything about Mars itself.

It's just stuff that's coming to Mars.

Well, but it's doing stuff to Mars.

When you say Martian bugs.

Oh, you don't know about that?

I'm not saying there aren't Martian bugs.

I'm just saying, are there Martian bugs?

Well, and then also are they attacking us?

Well, that was a slip.

There are no Martian bugs.

No, aren't there like microscopic life of some kind?

Well, that's what we're trying to figure out.

But the rad detector would tell you whether the radiation flux would sterilize the surface and kill all bugs.

Exactly.

Probably if there's bugs, microbes, whatever on Mars, they're underground because on the surface, there's no water, there's ultraviolet, it's freezing, it's nasty.

But underground, there might be water, it's a little more reasonable temperature, and you're shielded from the radiation.

But what we're trying to figure out is how deep do you have to be if you're a Martian bug, what's happening to the radiation.

And it landed where on Mars?

Because there's a lot of places to go.

You pre-picked a spot.

Yeah, we landed in a place called Gal Crater.

I've been there.

He does Thor a lot.

I actually named it after a friend of mine, Gale.

Gale.

It's not funny, she's dead.

Killed by a Martian I might have had.

It's by far the coolest place we've ever landed on Mars because...

Mr.

Universe has been there.

I've been to cooler places.

So, back me up here.

It's a cool place, right?

Because it's an ancient crater that used to be a lake and has all these sediments in it that tell us about the ancient past on Mars.

And it's got a five kilometer, that's three miles for you Americans, three mile high mountain in the middle of it that we're gonna climb up.

And it's like going up the Grand Canyon on Mars.

Every layer is from a different time in Martian history.

It's gonna tell us the whole story.

Mars rotates in 24 hours.

We rotate in 24 hours, right?

Well, actually not quite 24 hours.

What's the exact rotation?

Well, Mars is slightly slower.

It's like a half an hour longer in the day, which is strange.

So the people studying Mars, are they on Earth time or on Mars time?

They're on Mars time.

I actually was out there last week at JPL.

On Mars.

Well, I was at the Jet...

I was at the Power More for Partying in Mars, you know that?

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena where we're running the rover from.

And the day is on Mars time, which changes compared to California time.

And it's really an odd experience.

Wait, Mars time isn't the same as California time?

Well, sometimes it is.

But it sweeps past.

24 hours out of the day.

It slows down by half an hour a day, which is convenient if you're stuck in traffic.

But actually it's very weird because it gets to the point where it's completely the opposite.

And it's fine if you're a grad student or whatever and you're just doing that.

But if you have a family or whatever, it leads to divorces and psychosis and bad things.

So how many Mars divorces has there been?

I can't give you a precise number of them.

How come they always couch the mission statement in ways that where they're not actually saying, we're looking for life.

We're gonna look for water that could be like, we're looking for minerals that could tell you if there's water that, why all the subterfuge?

Because we don't know how to look for life.

We tried that once and we realized we didn't know what we were doing.

What do you mean, how do we try it?

Well, we had a mission called Viking, our first ever lander on Mars.

1976.

Yeah, and did all these experiments.

It's America's.

They were all like emails.

Why is no one responding?

The experiments worked and then afterwards we said, well, we still don't really know if we found life because we didn't even know what questions to ask.

And then we realized decades later, well, we gotta go back and do this a little more slowly and try to understand the history of Mars and what kind of life there might be.

Could it be that you cannot ask what something is if you only have one example of it?

Yeah, that's a big problem with astrobiology.

You cannot characterize life if as much as biologists celebrate what they call biodiversity, at the end of the day, all life has common DNA and common origin.

You are dealing with a sample of one.

And when you have a sample of one, you don't really have a science, do you?

No, you've hit on a problem.

Yeah, that's what I would have said myself, really.

This is a major problem for astrobiology.

We're studying something, we have one example.

How scientific is that?

Yeah, how do you define what life is if you only have one example of it?

Isn't there like some silicon-based thingamajig in a pond somewhere in California or something like that?

Yeah, I saw that episode.

I know that what I said was vague, but do you know what I'm talking about where there was like one thing that was found that had like a different element?

Oh, you're talking about the arsenic-based life.

Yeah, sorry, arsenic.

Yeah, yeah, no, that was really-

Arsenic-based life.

That was really hyped and possibly interesting, probably wrong, but it wasn't another kind of life.

That stuff was still carbon-based.

It just maybe had a different kind of DNA.

Give partial credit for-

You can only learn so much from USA Today.

Welcome back to StarTalk Radio.

Our next time capsule episode again comes from our live show at the Bell House in Brooklyn with planetary scientist David Grinspoon.

This time, he and the comedians Eugene Merman, Jim Gaffigan and Sarah Silverman talk about exploring the rest of the solar system.

We got messenger, and what's it?

Mercury, the little guy near the sun.

Mercury, and so what do we find there?

Well, there's ice at the poles, we think, which is really weird considering that Mercury is that close to the sun.

There's a much stronger magnetic field than we thought.

Wait, wait, so that would be ice, that would be ice where the sun doesn't shine.

Yes, yeah, it's got a much more complex history than we used to think.

We used to think Mercury was just a sort of, what we call an end member, just a dead, cold, small world, but it's got a complex, long volcanic history.

That's been a surprise.

It's more interesting and much more complex than we thought.

Okay, so next out, we've got Venus.

Who's at Venus now?

Well, there's a spacecraft called Venus Express, a little European space agency.

Because they had like a year to build and launch this thing.

They said, we got a spacecraft, if you can do it quickly.

So they put together-

Why did they have a year to do it?

Because there was a spare from Mars Express, and they said, whoever can come up with a mission quickly can launch this thing.

And so they came up with instruments and they sent it to Venus.

And it was actually amazing how fast they were able to do it.

And the thing has been in orbit for years and still working.

So it's basically our first weather satellite at Venus, which is neat.

It's also where we get those razor blades, right?

So what do we have in the asteroid belt?

Well, we actually have a spacecraft out there now called Dawn.

It's been orbiting an asteroid called Vesta for a while now and getting these really amazing 3D close up pictures.

And this is really like a small planet.

You know, we can get into what's a planet and what's not.

Maybe we shouldn't, but the largest asteroids are these round objects.

You might call them dwarf planets, even if you wanted to.

And it's been orbiting it for a while.

And what's cool about this is that this spacecraft has now left this asteroid and is on its way to another asteroid called Ceres.

And it's the first spacecraft we've ever had that visited one object in space, did a mission there and then took off and is heading to another object in space.

So it's our first time we've actually had sort of an expedition that could explore more than one planetary object.

There's nothing at Jupiter now, right?

Well, no, but we have a spacecraft called Juno on its way.

Well, it hasn't launched yet, but it's about to be launched to Jupiter and it's a magnificent spacecraft.

It's going to basically probe the interior of Jupiter by orbiting in such a way that we can measure the gravity and learn what it's like on the inside.

Sounds dirty.

To the word probe today, you know.

Well, we haven't gotten to Uranus yet.

So Jupiter's got Europa.

I love me some Europa.

Yeah, we don't have any missions on their way to Europa now, but we might.

NASA's top priority for a next big, what we call flagship mission, billion dollar plus missions.

Billion plus would be billions and billions.

Yes.

Thank you.

I'm sure we just shut down the schools in the states that don't matter.

We could easily afford to do this.

Yeah, exactly.

Europa's NASA's top priority target for next big mission, because it's one of the places where there ought to be life, if we're right about what it takes for life.

There's an ocean, we think, beneath this icy crust.

In fact, maybe our solar system's biggest ocean of liquid water there.

So we want to know that for sure, and we want to understand.

Kept warm, not by the sun.

Yeah, kept warm by-

But by the core?

No, no, no.

Well, kind of, but it's Jupiter's gravity.

It's the flexing of the moons in orbit around Jupiter's massive gravitational field, interacting with each other.

What if, in doing this, we opened up and all the monsters came out?

On to Saturn.

Yeah, we have a spacecraft there now called Cassini.

That's one of these Energizer Bunny spacecraft.

It got there in July 2004, and it's been making beautiful images of Saturn in the rings.

But the most astounding discoveries have been about the moons.

Titan is a moon of Saturn that is one of the most interesting places for us.

It's a very interesting place for astrobiology, because it turns out to be a very Earth-like world in some ways.

It's got rivers, it's got volcanoes, it's got clouds, it's got rainfall.

It's got coastlines, too.

It's got coastlines, but it's all made out of weird stuff.

The rivers are liquid methane, the rainfall is liquid methane.

The dunes are organic matter blowing around.

Wait, what do you mean organic matter?

Like carbon stuff, the stuff that we're made out of.

Like life?

Maybe.

Rivers of flowing life?

Maybe.

That would be scary.

It literally sounds like a James Taylor song.

So take me to Uranus and Neptune.

We got nothing to do with that.

You can say Uranus in a way that's like different from how people used to say it.

You can say like Uranus or something.

You want to hear something funny about that?

One time Carl Sagan told me that...

Name dropper.

I know.

But he told me that when he...

But if you're going to do it somewhere, this is a good choice.

When he was in school, the kids got all giggly about calling it Uranus because it had the word urine in it.

So you can't win.

In NASA's 10-year plan, the decadal survey that they just came out with, a very influential plan for the highest priority missions for the next decade, one of the top priority missions is a billion-dollar probe to Uranus.

We need Obamacare.

And so now we got a mission to Pluto.

We got one Pluto fan.

But we're headed there.

I'm glad.

Oh, yeah.

It's going to be awesome.

So it's a little spacecraft called New Horizons.

It launched in January 2006.

I was there at the launch.

Sounds like an airline magazine.

It was incredible.

It was the fastest object ever launched from Earth because it's got a long way to go and is most of the way there now.

It's getting there in July 2015.

Welcome back to Star Talk Radio.

This time capsule show features fan favorites, and for many of you, my interview with the controversial podcaster Joe Rogan was a season four highlight.

So Joe, you always talk about science.

It infuses almost everything you do.

Because all of it, the physics, biology, chemistry, engineering, there's gotta be some force operating.

What is it?

With me?

It's just curiosity.

I just think we live in extraordinary times and the ability to access information is so unprecedented.

How often is science material for you?

A lot, yeah.

Some of my best bits have involved science.

Is there any quick one you did?

Well, I know that the mood isn't there or whatever.

No, no, it's not even that.

It's just my style of standup is more like these long chunks.

Had you heard the one about this?

Yeah, it's not like a one-liner.

You know, like one of them is the anti-evolution of man, which explains like pyramids and the ideas that we are the bastard children of the idiot stone workers of Egypt.

And what happened was the dumb people just outfucked the smart people.

And it just got to a point where there was no smart people left.

And the bit was about like how many of us really, truly understand how this world operates.

And I would like tap on a microphone and go, why is that loud?

I'm a standup comedian.

My whole life depends upon this, but I have no idea how this works.

I just get up here and I do my job.

And I'm like, how many of us understand how the power is on?

And if the power went off, what would you do?

One day, we're going to out-fuck all the smart people and there's going to be no smart people left because women, they want to have sex with rappers and baseball players.

I mean, maybe you, you're like a celebrity scientist.

I'm sure you get a lot of hot college chicks that are knocking it your way.

But like for the average dude involved in science, there's very few opportunities to breed.

For sure, the podcast represents me in a better way than anything I've ever done before.

It's easy to have a perception of someone, but how well do you really get to know someone unless you hear them talk for hours and hours and hours and end?

And I think that anything else I've done, whether it's hosting the Ultimate Fighting Championship or Fear Factor or what, even Stand Up Comedy, it's going to give you like a sort of a limited view into how a person functions.

It's sort of like you're operating in a very specific bandwidth or very specific frequency rather.

Whereas with the podcast, frequency bandwidth.

We talk about everything.

Frequency bandwidth, I like the words.

Keep the vocabulary coming.

Do physics vocabulary.

I'll grade it at the end.

See how you did on all your vocabulary.

I'll be happy with a C.

But with the podcast, it's really anything that I find curious.

And that has resonated with a lot of folks that I think felt like they were unrepresented before.

The idea of needing attention is a trip.

And the idea essentially comes from in the ancient days of human beings, the person who got the most respect was the one who was the most successful in the hunt, the most successful in battle, the one who was the most successful in breeding.

That lead was to be followed because there was benefit in being the leader.

There was benefit socially.

There was benefit sexually.

And they had more offspring as well, right?

And as I said, we were talking about before about reward systems built into our genetics.

Well, these reward systems are now hijacked in this weird way where you can kind of circumvent all regular reality, like all hierarchies, and all you have to do is get a camera on you where other people see that and you get some benefit.

And it's really, really strange.

It's a strange aberration, a strange sort of a blip in the matrix where you get like this Kim Kardashian type human, where you just get someone who's famous for having a lens put on them.

And that is essentially it.

There's not that much interesting going on.

You know, there's prettier girls.

There's certainly smarter girls.

But because this lens is on, there's a great amount of power and energy focused in this one really mundane spot.

So it's a perversion of evolutionary features that exist within us.

Yeah, I think so.

Do you think science literacy, if every fighter had it, would improve their fighting?

Yes, unquestionably.

Because a lot of fighting is hindered by emotions.

And I think science literacy would benefit fighters extremely.

I think that, as I said before, technique is the most important aspect of martial arts.

And technique, up to a point, allows you to overcome physical advantages.

And that's very scientific.

And I think that the ability to use leverage and the ability to understand force and mass, all of that applied with the understanding of the cardiovascular system, the understanding of the scientific principles of nutrition and rest and recuperation, all of that would unquestionably benefit not just fighters, but any athlete, anyone involved in doing anything that's difficult where you're competing against other people that are also trying to do their best.

Science really changes the entire game.

Science changes entire game.

We're wrapping up our season four time capsule with our episode on asteroid mining.

The show featured my interview with Peter Diamandis, who not only created the X-Prize, but also co-founded the asteroid mining company, Planetary Resources.

We now have the ability privately to go out and begin to extract resources from asteroids.

You know, much of humanity's exploration, much of humanity's growth has been a function of gaining access to resources.

Whether it's the Silk Trail from Asia, whether it's Europeans looking to the New World for gold and spices, or American settlers looking to the West Coast for timber, land, gold, oil.

That's what's driven us.

It's driven us consistently.

And so as I...

Yeah, think about it.

Why are the 49ers called the 49ers?

Because in 1849, there was the Gold Rush in San Francisco.

There's people moving body and soul.

And that drove the creation of the railroads.

It drove different parts of the United States to be literally settled, Homestead Act and so forth.

And so people were looking for resources that would create value and uplift humanity in that regard.

How do we connect opening the space frontier to what I call an exothermic economic reaction?

Meaning how do we connect it to something that makes a profit that consistently drives us?

Exothermic, that is the release of energy, more than what you put in.

Yeah.

Yes.

And as I think about this, space has tremendous value.

Everything we fight wars over on earth, metals, minerals, energy, real estate, those things are near infinite quantities in space.

People look at the earth as a very closed system, but the earth is a crumb in a supermarket filled with resources.

And if we can gain access to those resources, it uplifts everybody.

We are building the very super low-cost deep space satellites, satellites that can go beyond low earth orbit, millions of miles and consistently accurately operate out there, communicate back by laser, have super high precision pointing, have big optics to look for asteroids, and ultimately go out to them, prospect them, understand what they're made of, put a beacon on them as the first step, and then be able to extract valuable resources.

Okay, so there's a whole prospecting phase.

How long is that?

We're going to be prospecting for decades, I'm sure.

But we're launching our first of what we call the ARCID series of spacecraft within 18 to 24 months.

And these ARCID spacecraft are space telescopes.

They're telescopes that in low earth orbit are able to see asteroids coming whizzing by the earth.

The second iteration of the ARCID spacecraft are going to have propulsion that you see it coming by, ignite the engines and go on an intercept course.

Okay, so first you see that they're out there.

For now you chase them down.

Chase them down.

Bag them and tag them.

Bag them and tag them, all right.

I think we're going to call them officially the bag and a tag mission.

I mean, we look at three phases.

Phase one, ARCID 100 are spacecraft in orbit of the earth trying to characterize and find these near earth approaching asteroids.

That's the prospecting, next.

We go out phase two, the ARCID 200 spacecraft are propulsion on them.

They're going out to actually tap these spacecraft, put a beacon on them, dock with them and be able to actually characterize them.

What are they made of?

How big are they?

So one is telescopically.

The next one is.

So the next one actually has the same telescope on board because they're going to be using these telescopes to actually look at them and point at them as you're going close.

Because these things are moving at tens of thousands of miles per hour.

And you need to be able to accurately track them down and go and dock with them.

But once you dock with them, now you're there.

Now we're putting a beacon on them.

Then the third phase ultimately is going to be, as you said, bag them and extract the resources.

So the question is, can a private company own it?

And ultimately, what is a celestial object?

You know, not owning the moon, I can buy.

But you know.

Don't say I can buy.

Use a different phrase.

Not only moon, you can agree with.

Yeah, owning the moon, I can agree with.

But owning a 10 meter rock in space, I mean, where do you draw the line?

And if you can't own the asteroid, can you own the materials you extract from the asteroid?

Just like, you know, you don't own the ocean, but when you pull the fish out of it, you own the fish.

So somewhere in there is a structure that will be defined over this next decade because we're gonna drive it to be defined in a way that ultimately allows for business to exist because if you can't have ownership, no one's gonna go out there and extract materials and the loser is humanity because the fact of the matter is once you can extract these resources, everybody wins because it becomes cheaper, that drives new battery technology, medical technology, electronic technology that we all benefit from.

It sounds like that's the frontier of the new trillionaires.

I think it is.

I think that the first trillionaires will be made in space.

But as a result, it's upping the economic growth of humanity, not just any one individual.

In summary, it will have an effect on the free market trade, but it's not a bad thing.

No, it's a great thing.

In fact, that's the way science works.

Genome sequencing used to cost a billion dollars.

Today, it's $1,000 and dropping.

Energy, over the last hundred years, the cost of food has decreased 13-fold, the cost of energy has decreased 20-fold, the cost of transportation.

So we're spending a smaller fraction of our paycheck on food than ever before.

Ever before.

And the cost of transportation.

It's not hurting our calorie input either, apparently.

But think about it, the cost of communications has dropped 1,000-fold.

So that's what technology does.

And hopefully, if we do our job right, these metals that are valuable for society will get cheaper and cheaper and cheaper.

You've been listening to StarTalk Radio, brought to you in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

Until next time, keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron