About This Episode

How do we uncover distant planets’ secrets? Neil deGrasse Tyson and comedian Chuck Nice explore the recent discoveries in exoplanet study, exo-moons, and finding the stars from our sun’s stellar nursery with astronomer and head of Cool Worlds Lab, David Kipping.

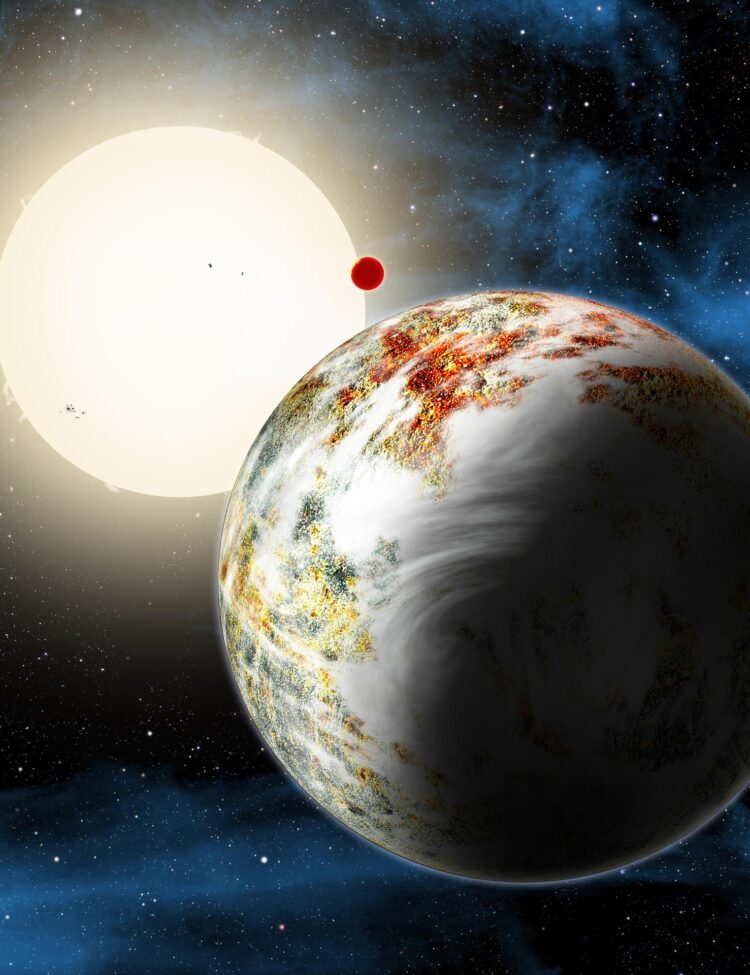

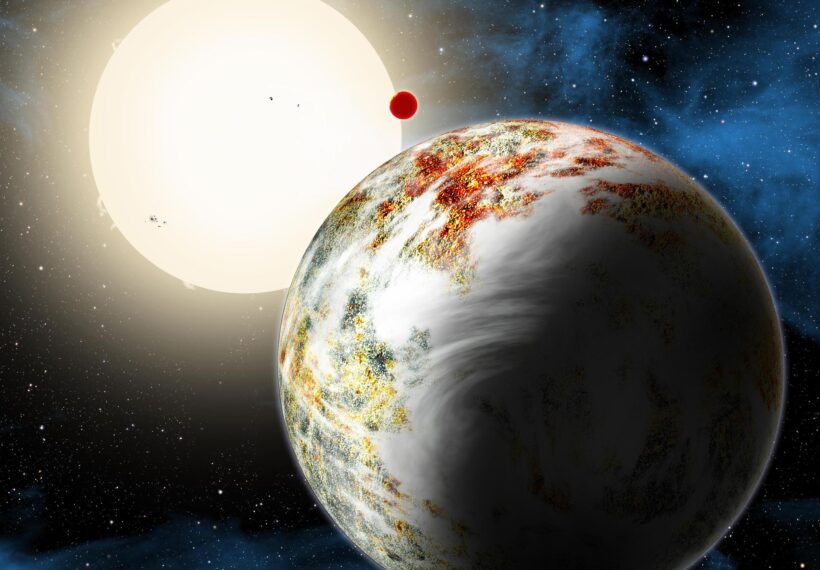

Learn about “Cool Worlds”– planets that exist in the colder, outer regions of space. The discussion dives into the science of exoplanets, exo-rings, and the enigmatic exo-Trojans, revealing how these distant worlds differ from our own solar system.

Taking insights from the James Webb Space Telescope, we explore Kepler-167e, a Jupiter twin, and its potential for exomoon discovery. We explore the birth of our solar system, the search for the Sun’s lost siblings, and the idea of rogue worlds– planets that wander the galaxy, untethered from any star.

We expand to include rapidly spinning stars, the process of aging them through gyrochronology, and the groundbreaking discoveries of JWST, such as binary Jupiter-mass objects. Plus, we cover plans for the Habitable Worlds Observatory, a next-generation telescope aimed at directly imaging the surface of exoplanets and potentially finding signs of life.

Thanks to our Patrons Micheal Morey, Kristoff Vidalis, Adir Buskila, Yanir Stein, Randombot38, James Komiensky, Richard Clark, Daniel Helwig, Kayleigh Sell, and KENNY SMART for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTSo Chuck, we went everywhere on exoplanets.

We got from planets to the ingredients of the entire universe.

So that’s how much was covered in this show.

And exoplanets with moons.

Yes.

You know, we’re thinking just it’s a planet, but why can’t they have a moon?

We got a moon, give them a moon too.

Exactly.

And so we have people interested in the moons of exoplanets.

Yeah, and we can actually.

Well, they never be satisfied.

That’s what I’m saying.

Like, when does this end?

All right.

A lot of exoplanets coming up on StarTalk.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This StarTalk, Neil deGrasse Tyson, you’re personal.

This is Chuck with me.

How you doing, man?

Hey, what’s happening?

Doing all right?

Doing great.

Doing good.

Nice.

A little while ago, you recorded a comedy special.

Yeah.

But it hasn’t aired yet.

We have to sell it.

Anybody knows anybody at Netflix?

I need my money back.

I’m telling you the truth, people.

I was going to do like one of those, like what are they called?

GoFundMe.

GoFundMe.

But I was like, okay, no, listen, if you believe in yourself, go ahead, put out the money, you’ll get it back.

You got the talent.

Don’t worry about it.

I should have did the GoFundMe.

Oh, then I hope you were saying that about yourself.

No, but hopefully, we’ll be out very soon.

We’ll look for that.

So it’s another Cosmic Queries today, and it’s bespoke.

Very bespoke.

It’s not a grab bag.

That’s right.

And the topic is cool worlds.

What?

I know like a little bit about cool worlds, but I don’t know enough to do a whole Cosmic Queries on it.

So we combed the hood.

Yes.

And up the street is an entire university, right?

Called Columbia.

It is.

That’s where I got my PhD.

Right.

Columbia.

Yes, it’s the…

It’s the Ruckers of Harvard here in New York City.

What?

So we have a professor of astronomy from Columbia.

Yes.

David Kipping, welcome.

The leader of all cool worlds.

I’m the man right here, yeah.

Thank you for having me guys.

Yes, so you have…

You’re head of the cool worlds lab.

So, since you’re a scientist, not a hipster, I have to believe that the word cool references temperature and not attitude.

It’s a bit playful, but yeah, we’re not dope worlds lab.

That’s what you should have named it.

That would be amazing.

You should have named it dope worlds lab.

Oh, you’d lost that opportunity.

My proposals might be a bit tricky if we have that on the tagline, but…

Check my temperature, yo.

Because my planet’s a dope.

Well, sick.

We could go sick maybe next to the world.

That’s a no.

Yo, you ready for this?

Sick worlds.

I’m done with the kids.

I’m sorry you caught me on that one.

It’s been my experience that anyone who says I’m down with the kids is not down with the kids.

All right.

So, cool worlds.

We’re referring in your particular case to worlds outside of our solar system, exoplanets or exoplanet moons.

Anything exo.

Any exo rings and exotrogens.

You can throw it all in there.

Exo comets, you go.

Okay.

Well, tell them what you mean when you say exotrogens.

Because he’s thinking.

You saw me, I went.

You saw what I did.

So I was just like, I’ve heard, I’ve heard of the birth of a star.

I’ve heard of that.

Where they don’t use trojans.

Yes.

But the trojans are like.

Why are we going back to ancient Greeks?

Yeah.

This is around Jupiter.

There are these additional small bodies called trojans and they’re in the Lagrange point.

So Jupiter, as it goes around its orbit, it looks 60 degrees off axis on either side.

There’s the Trojans and the Greeks.

And it’s these small collection of asteroids and small bodies.

And so we think we could detect those around other stars.

And so then there would be exo-virgin.

Put exo in front of anything.

Good to go, that’s the branding.

Put exo in front, put some exo on it.

So that Lagrange point is the sun and Jupiter.

So that would be, I guess, L, one, two, three, four.

L, three, four.

We did a whole thing on the Lagrange point.

Yes, we did.

We did.

This is why, and people say, when I say things like right or okay, they think I’m just playing along to look like I’m like, oh, I’m in on this.

But what they don’t understand is that we’ve talked about this stuff, and what’s happening is it’s coming to my memory and I’m like, right.

Okay, okay.

You should have an honorary PhD.

Not at all.

You’re almost there, right?

I’m not.

I’ll find some certificate out there.

See, I’m afraid to receive that just because they’re like, oh, you should know a lot more.

Chuck, you should actually know a lot more than you do.

This can’t be right.

So our solar system is a template for you to think about and imagine what could exist in other star systems.

Indeed, yeah.

That’s fair to say.

Yeah, exactly.

Okay.

Are there any super anomalous solar systems that you come across that are just so unlike ours that it really perks things up or do most of them just kind of fall in line?

But I’m going to answer for him.

Oh.

All of them.

Really?

Okay, now go.

You give your answer.

I would say you’re not too far off.

Yeah, I would say that the majority of solar systems look radically different to that of our own.

That’s amazing.

Yeah, you have binary star systems, which, you know, are very, very common.

That’s a half of all the stars you’ve seen in the night sky.

I have multiple stars.

Two or more.

And just off the bat, that makes it unusual.

Even having a Jupiter is unusual.

Only 10% of single stars have a Jupiter-like planet.

So just having not just one but two Jupiters in our solar system is already kind of unusual.

So two Jupiters would be Jupiter and Saturn.

Yes.

I’m going to throw Saturn in.

Because it’s the same size.

It’s a very different mass.

But it’s roughly the same size.

But be nice to it.

Because Saturn is one of my…

See my desk lamp here?

Oh, you guys can’t see.

No shade on Saturn.

It’s beautiful.

My desk lamp I hand made in a wood shop in seventh grade.

And it’s a ring.

It’s made of wood.

And it’s a ball and a ring.

And you press down the ring and the ring tips, and it turns the light on.

So me and Saturn go way back.

Don’t just lump it in with Jupiter.

And he only lost one finger, maybe.

That’s what you started.

But in my notes here, it says there’s a YouTube channel on this?

Yeah, I’ve got a, yes, my team is called the Cool Worlds Lab at Columbia University.

We’re a research group of currently four graduate students in my team, and we’re studying all different projects, looking for exo moons, looking for these weird phenomena around these cool planets.

But at the same time, when I first arrived at Columbia, which was about eight years ago now, I decided one of the things I wanted to do was also talk about science, as you’re well aware of the importance of doing that in popular culture.

So I started a small YouTube channel, didn’t think Hullian would watch it, but during COVID, many people decided for whatever reason, they were interested in astronomy.

And you post there about it with what frequency?

Usually once every three weeks or so.

Yeah, so it’s, I mean, I have a full-time job doing my research, so I can’t post that as much as I’d like.

People moan about that all the time, but it keeps things fresh by having one foot in research and one foot in this.

I can’t watch.

Yeah, otherwise you get stale in both.

Perhaps, yeah.

That doesn’t happen.

Now, you said you have four graduate students.

When someone boasts of how many graduate students they have, it means there’s actually a lot of work that needs to be done.

And they will do work because they need to get their degree and you alone stand between them and their degree.

Well, that’s too much power for one man to handle.

Oh, that’s terrible.

Great power.

We have evidence that there’s life after this arrangement.

One of your former students we’ve had as a guest on StarTalk, who was that?

Did you?

Moira McTeer.

Yes.

Dr.

Moira McTeer.

She was one of my first PhD students.

You get to say doctor.

It came through.

By the way, that doctor is courtesy of me, Mr.

Kipping.

Yeah, it does feel like an honor to bestow, help these students get to that point.

I mean, I will actually come to the defending the PhD.

It’s not just my decision, of course.

I’m actually supposed to keep my mouth shut and let the other people decide.

There’s actually a committee that puts you through the wringer.

They’re not there to be nice to you.

They’re there to stump you.

And the less stumpable you are, the better a scientist you become.

I gave all my PhD students, I think, a lightsaber, so I think Moe has one buried in her cupboard.

Just in case.

Yeah, just stow upon her with a lightsaber, her PhD.

No, no, but the thing is, an actual saber will stop at your shoulder, whereas a lightsaber won’t.

This is just a toy lightsaber.

We’ll let people know that we can actually have real lightsabers out there.

Right.

You can tell all of Dr.

Kipping’s students because they have a very significant burn.

It goes from their shoulder to their navel.

In any way tonight.

So, tell me, before we get to our Patreon questions, tell me, what are some of your challenges?

How much of what you do is theory or modeling or observations?

What telescopes do you use?

Do you have a favorite spot in the universe?

Using Kepler data.

What feeds your operation?

It’s a big bag of all sorts of stuff, to be honest.

I mean, I’m kind of glad that you didn’t ask, are you a theorist or an observer?

Because I really don’t like labels like that.

I kind of feel like if you call yourself an observer, you know, somebody goes to the telescope, looks for different objects in the sky, it kind of limits your mind space, right?

So now you think, well, I can’t do the hard theory stuff because I’m an observer and vice versa.

I try to keep my feet sort of in every pocket as I can to try and stay nimble.

But the data set we’re excited about at the moment is JWST, of course, like many people, that’s the…

JWST is touching everybody.

Everybody, yeah.

Not in that way, but in the good way.

Sorry, you weren’t thinking that.

You’re just, okay.

I like it, though.

So it’s infrared data of what objects?

The observations we’re planning in October will be of a Kepler planet, actually, called Kepler 167E, just rolls off the tongue.

Why Kepler?

Why is it Kepler?

Kepler was great for finding cool worlds, because it was very patient.

So it stared at the same…

Kepler’s been dead for 400 years.

Not Johannes Kepler.

Oh, thank you, okay.

We should not be thinking about Johannes Kepler, but the telescope named in his honor.

There you go, okay.

There’s a telescope.

Listen, so we got a medium, and it appears the Kepler says, there’s this planet.

Okay, but go ahead.

So this planet was discovered by the Kepler mission, I should say, the NASA Kepler mission.

And it was a planet actually I discovered, curiously enough, and it turns out this is pretty much the best planet for looking for exomoons out there.

It is a…

Exomoons.

Exomoons.

It is a Jupiter twin.

It has the same mass as Jupiter within 1%, the same radius within 5%, has the same equilibrium temperature, it’s the same kind of coldness, if you like, as Jupiter.

It’s in a similar kind of system, a multi-planet system, everything’s just like boom, boom, boom.

Everything looks like Jupiter.

And Jupiter has a bajillion moons of its own, and so presumably that’s the case here.

Yeah.

Can I ask maybe a dumb question?

I just want to emphasize here that you’re about to make progress using a telescope that is building on the progress of a previous telescope.

That’s right.

Right.

So it’s not just people pulling stuff out of nowhere.

We are all standing on the shoulders of hardware that came before us.

Oh yeah.

Amazing.

I’m at the end of a, you know, this is a 12 year personal journey trying to find these exomoons for me at this point.

So we thought we’re still winning.

We’re hoping this is going to be the one.

So this is my question about exomoons.

So now when you’re looking at the planet, it’s pretty easy because you’re looking for it to transit the star.

Now, if that’s how you’re finding the planet.

That’s how Kepler found all of this planet.

If Kepler found all this.

The transit, the eclipse was in front.

Are you looking for the reflection of light off the planet for the moon to transit in front of the planet?

Or are you looking for the moon itself to also transit the star?

Where is the blockage of light that lets you know that this is indeed a moon?

Translation, how the hell do you detect it?

Short answer is option two, you kind of said it.

We look for the shadow of the moon in front of the star.

So if the planet, it’s a shadow really, that blocks out starlight, that gives us this dip in starlight.

If there’s a moon there, it will either be trailing or behind and so we’ll see this little extra dip in light.

And it’s that, so we see two dips, one huge one due to the planet, and then we zoom right in on that data and hopefully we see a tiny little one due to the moon, or even multiple, maybe multiple dips, of course.

Yeah, but wait a minute.

Okay, so you’re in a cool worlds lab, but all you’re getting here is a cool shadow.

And I feel like Plato’s cave right now.

You don’t know, Jack, about the object that’s making that shadow.

No, it’s a limited technique.

I mean, what we get from this is essentially the size of the object.

We can figure out how far away from its planet it is, it’s some major axis, and maybe we can figure out some other things such as its orbital period, its inclination.

So just the bare bones.

The bare bones, that’s not a world yet to me.

No, I think that’s fair.

A world is what’s going on on the surface.

Yeah, but we will get there.

I mean, we’re hoping to build telescopes like the Habitable Worlds Observatory, HWO, which might get rebranded one day to something else, perhaps like Coliseum Observatory or something.

Uh-huh, that sounds good.

That could be fun.

Let me tell you something that’s gonna get you a lot more play than Habitable World.

I don’t like the name.

I can barely say Habitable, so I don’t.

Yeah, it had to be Habitable, yeah.

But this telescope will take actual photos of planets one day, and so then we really would get a sense of its color, its atmosphere and maybe even some surface properties.

So we’ll get there, but it’s all baby steps.

You know, you can’t just jump straight to the end.

And you won’t be able to see dinosaurs walking on it.

No, no.

You’d need a telescope even larger than the sun to have any chance of that, yeah.

I’m Nicholas Costella, and I’m a proud supporter of StarTalk on Patreon.

This is StarTalk with Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Well, I’m impressed that we were able to solicit questions on this very bespoke topic.

And we got a lot of them.

Cool worlds.

I mean a lot of them.

So let’s pivot.

People like you.

People love the cool worlds.

And maybe they could be fans of your YouTube channel even.

That might be one or two, but no, no.

Don’t sell yourself short, David.

Don’t underestimate that.

Don’t sell yourself short.

Okay.

Here we go.

Hello, Dr.

Tyson, Dr.

Kipping, Lord Nice.

I am Sai from Kakinada, India.

Chuck, I thought we can test your pronunciation on names of towns this time.

Really?

Don’t do that.

These people, what’s going on?

They’re trying to bring you along, Chuck.

Trying to help you.

My question to Dr.

Kipping is, in your studies, you’ve worked with the concept of occultations.

To detect exo-moons and planets, could you paint us a picture of how this works?

And are these the most important cosmic breadcrumbs, according to you?

There was a famous astronomer, Henry Norris Russell, in 20th century, he once said that eclipses are the royal road to success.

Interesting.

I love that quote.

It just goes to show you how eclipses are like a shortcut.

They allow us to see things that’s kind of ahead of our technology yet.

Like we shouldn’t have the ability really to know anything about 5000 exoplanets because we can barely take images of nearby planets.

It’s still something we’re struggling to do.

But using this trick of seeing a planet pass in front of a star, it gives us an extra window.

And it only works in some cases.

You have to have just the right alignments.

You have to be lucky.

But when you get that lucky fortuitous alignment, it gives you this unique ability to probe all these extra things like the period, the semi-draxxus, the size of the planet.

So it’s our first luck at these things.

Just to be clear, you’re only seeing systems that happen to be edge on to your field of view.

Or nearly edge on.

Let me say that in the negative.

None of the other systems are going to give you these eclipses, these transit phenomena.

And so they go undiscussed, unrecognized, uncatalogued.

For now, for now.

We’ll get them one day.

Look at that.

Of course, we can get some of those using other methods.

For instance, the radiovelocity method has also been very successful.

Not as successful as transits, but that’s discovered hundreds of plants in its round rate.

Now you have to tell us what the radiovelocity method is.

Okay.

So this is wobbling stars.

So as you see, if you look at a star’s light and you see it being blue-shifted a little bit, then periodically red-shifted.

That is telling you it is moving back and forth.

When it’s blue-shifted, it’s coming towards you, red-shifted away from you.

So it’s just like the siren of the ambulance going down the street.

Whoa, what a nice, I like the picture.

Yeah, you see the pitch change.

When we hear that pitch change, or when you see a pitch change in the color of the light of the star, that is telling us that something gravitationally is tugging on that object, and that’s how we can infer planets indirectly.

So there you don’t need the precise alignment, although if it was completely 90 degrees off, we would see nothing, because then the star would be doing this, so you’re kind of wobbling in the plane, and so we wouldn’t have any blue-shift or red-shifts.

Not coming towards you or away from you.

Yeah, exactly.

But most of the time we can still get there.

I think what we have in our favor, because I did this calculation now 30 years ago.

I haven’t done it lately, but I don’t see why the math would change over time.

But if you do this, you are statistically more likely to discover edge-on systems than face-on systems, if you do the math on that.

David’s looking at you like, as your peer, I’m gonna have to review that.

Let’s go to the video chat.

Let’s go.

All right.

So what else you got?

All right, here we go.

So this is Lisa Cotton.

She says, Dear Dr.

Tyson, David Lord, nice greetings.

This is Lisa from North Hero, Vermont.

I’m a fan of both StarTalk and Cool Worlds, and I love watching both shows on YouTube.

One thing that I have been pondering lately is the birth of our star, the sun.

It seems like a lot of talk happens about when the sun dies.

What I would like to know is, was our sun born in a star nursery?

And if so, would we know which one, or be able to predict where it might have been or come from in the Milky Way galaxy?

Thank you so much, and keep up the excellent work.

We love this.

We got good fans out there for this.

Yeah, that’s a really intriguing question.

And it’s a question that I know many of my colleagues are thinking very hard about, even at Columbia.

So, of course, the sun must have been born, we think, in a stellar nursery.

And so there would have been siblings born alongside with us from that giant molecular cloud that collapsed and fragmented and formed all these small stars.

We don’t know exactly how many, but there’s probably many such stars.

And the question is, what happened to them?

Over billions of years, the stars will disperse.

They’ll move into slightly separate directions.

And especially because of tidal forces from the galaxy, they’ll get kind of pulled apart and could be essentially long lost siblings at this point.

You know, spread across half the galaxy or more.

And the sun, given its age and its speed, it’s been around the center 20 times.

And so if it had a whole family 20 times around, given everything you just said, that can happen en route, you know, your siblings are long gone.

They should be out there.

And so an interesting question is…

Guys, when are we getting together?

Yeah, we won’t have a reunion.

You guys never stay in touch.

Give me Zoom.

We’ll do it next time.

A family reunion might be possible, at least in a sense of discovering them, by actually looking at the chemistry of those stars.

So there is an active effort to measure the detailed chemistry, the abundances of every single element you can think of inside these stars and compare them to that of our sun.

And these sibling stars should have not only the same age, of course, but also the same chemistry.

So a gas cloud not that far away would still have all these elements but not in the exact amounts relative to each other.

Yes.

That’s like a fingerprint.

Yes, exactly.

All right.

So there should be a unique chemical fingerprint.

We’ve got people looking to get the family back together.

Get the band back together.

I don’t know the latest on that, but I know that there are many astronomers who are hunting hard for those.

And I think we’ll probably hear big news when they’re discovered.

Let me restate that question, but in another kind of way, because we can’t see the birth of the sun, having happened in our past, but we see the birth of other stars.

Nobody made a videotape, unlike people who really disturb you by trying to show you theirs.

So how much insight are we getting now that we can see stars being born with their planets?

How much insight from these other systems do we then bring back to ours?

There are some startling things we’ve discovered.

I mean, one thing from direct imaging, which is actually taking photos of these young planetary systems in the process of forming planets.

Catching in the act.

Right, I mean, they’re very young, hundreds of millions of years old or less.

That’s young.

That’s young in cosmic terms.

One thing that’s very startling about these is we see, and I mentioned earlier that Jupiters are rare, but that’s in mature systems.

In these young systems, we actually do find lots of Jupiters.

And what’s strange is that they’re really, really far from that star.

They’re on order of hundreds of AU.

So an AU is the Earth’s orbit around the sun.

So, I mean, Astronomical unit.

Yes, Jupiter is 5 AU, Saturn, I think, is about 10 AU.

So these things are 10 times more than that.

That’s sort of the distance where we talk about looking for planet nine.

planet nine is being a hypothetical planet.

The solar system is really, really far out.

And we’re discovering Jupiters very often that far out.

And they’re very massive.

They’re actually bordering on brown dwarfs, which are like sort of 10 to 20 times the mass of Jupiter.

And that is a mystery.

Maybe the solar system then also formed such planets, but they were somehow lost.

Because these things are so far out that they may be tenuously held gravitationally and will be stripped away.

And there is an act…

They would be, what do we call them?

Bagabond planets?

Rogue worlds, yes, free-floating planets.

There’s recently there’s discovery of what’s called jumbos, which is pretty interesting.

These are Jupiter…

That’s an acronym on…

Jupiter binary mass objects, I think.

So these are two Jupiters and these are free-floating.

So not just one Jupiter hanging out in space by itself, but two of them orbiting around each other.

And we can understand how maybe one Jupiter could get kicked out of its solar system.

But how the hell do you end up with two bound to each other?

And they’re right, and they’re together.

Yeah, that’s so weird.

We don’t understand those.

Those are jumpers.

Recently discovered by JWST in the Uranus Nebula.

If they do something stupid, we call it a bimbo.

Like that.

Ooh, wow, what a great question.

Good for you.

All right.

Look at all these questions you’re scrolling through here.

Oh, I’m telling you, this is like unbelievable.

These people, we have great listeners.

That’s all I can say.

This is Gabriel, and Gabriel says, hello fellow stellar satellite riders.

Gabriel here from Okinawa.

What’s the fastest rotating star?

We have found per pre-nova.

And what would hypothetically be the fastest possible?

How does this rotation affect the star’s atmosphere, fusion and life cycle?

Thank you and love you guys.

Ooh.

Yes.

These questions are getting in.

They are.

Laser focused questions here.

Yeah, so stars all spin.

The sun is spinning.

I think its rotation period is about once every 27 days, something like that.

And that’s not untypical.

Many stars have similar rotation periods, but they change their spin over time.

So they actually tend to spin down.

So again, if we go back in time to when the sun was young, it would have been probably spinning much, much faster and probably arguably close to its breakup speed.

So there’s a certain speed called breakup speed, but it’s rotating so fast that the centrifugal forces outwards are comparable to the gravitational forces inwards.

That’ll break up any relationship, you know?

Yeah, you don’t want to spin too fast in any relationship.

So stars are probably, when they’re very young, have these extreme rotation speeds.

One thing I actually learned from one of my, one of your colleagues right here at the Museum of Natural History in recent on my podcast and the Cool Worlds podcast was that-

The Cool Worlds has a podcast?

We do.

You don’t only have a lab, you got a YouTube channel and a podcast?

Yeah, I just slipped that plug in.

Okay, very nice.

I didn’t know I did that.

So we had Jackie Farty on my podcast.

Jackie Farty, yeah.

She was telling me that some of the brown dwarfs are rotating close to that kind of break up speed as well.

And they seem to have rotation periods of order of hours, which is incredibly fast.

And they were essentially almost stars.

They’re just below the masses of stars.

So she doesn’t like the word failed stars.

I’m not going to repeat that.

That’s exactly why I said it.

That’s exactly why I said it.

Those are objects of interest.

Failed stars, is that correct?

I was joking.

So, you know, it’s interesting.

Why do those brown doors, which are presumably quite old in many cases, still got their rotation and the sun has lost most of its rotation.

And we think it’s probably from an effect called magnetic breaking.

So the sun has a strong magnetic field and from that magnetic field, it accelerates ions and particles along those field lines.

And they basically get kind of ejected out of the solar system.

And once they kind of leave the heliopause and get really far away from the solar system, they essentially decouple from those field lines and then they just carry away what’s called angular momentum, spin energy, essentially from the sun.

So the sun basically by throwing stuff out, imagine you’re on a merry-go-round and you’re spinning really fast and if you start throwing stuff in the opposite direction to your direction of spin, you could slow yourself down and it’s kind of doing the same thing.

And so over time these stars break and slow down and we can actually even use that effect.

You call it magnetic breaking.

magnetic breaking.

Again, another…

As opposed to electric boogaloo breaking.

Which is in the Olympics this year.

Yes, it is.

We have a whole episode on breaking, on breakdancing.

So this is a cool effect and yeah, I was going to say Ruth Angus, who’s here at the museum as well.

There’s another museum right here at the Museum of Natural History.

Yeah, you guys have the superstars.

The Department of Astrophysics.

We got some good people.

Good people and she’s been showing that you can use this to age stars.

So you can actually use the speed to figure out how old the star is.

To age date them.

Yeah.

Yeah, it’s called gyrochronology.

Wonderful.

Gyrochronology.

Yeah.

What else you got?

All right, here we go.

This is Zach Metty or Metty, no, Metty, who says, good morning or afternoon, Dr.

Tyson, Dr.

Kipping and Lord Nice.

My name is Zach Metty from a boring town of Hermitage, PA.

Don’t diss your own town, man.

Because you’re from, you’re from…

I’m from Philly, originally.

You’re from Pennsylvania.

Yes.

So, all right.

He says, my question is, since we’ve upgraded from the Hubble Space Telescope to the James Webb Space Telescope in our orbit, will we eventually upgrade again if we do?

What would be the goal of the new telescope and what would be expected of it for discovery?

I like people like that, that never rest on whatever you have.

He’s like, good for you.

I’m on to the next.

What have you done for me lately?

I’m done with James.

What’s next?

I’m done with this.

What have you done for me lately?

What’s next, man?

And what are we going to expect from the next?

I get that.

I get that.

We always want to see the trailer for the next sequel, right?

So, this is it.

So, people are thinking about that really hard right now.

And it seems like a lot of people are converging around the idea of some kind of direct imaging mission.

So, we want to actually take photos of these distant exoplanets.

And the leading candidate that people are currently converging on is called the Habitable Worlds Observatory, HWO.

And it may be rebranded.

We’ll see.

I don’t really like that name too much at the moment, but it might be rebranded.

And the plan is to build something that’s about six meters is what the Decadal Survey recommended.

This is every 10 years, astronomers come together and they all pitch in their ideas and try to converge on what they think the best ideas are and the one that flows.

That’s why you rarely see us fighting with each other about what should get funded.

We go through this very elaborate process, where our most trusted among us are put in a room and they don’t come out until they agree on…

Octagon of…

Six astronomers enter.

One astronomer leaves.

It’s the Funding Thunderdome reality show.

Speaking of the Decadal Surveys, has the Habitable Worlds Observatory showed up in one of them yet?

Yeah, it was the top recommendation in the last.

In the very most recent one.

And JWST would have been in previous ones.

So they’re coming in…

And Hubble before that.

And a decade or two before the real thing happened.

So anyone wants to eavesdrop on what we’re thinking.

Right.

That’s how you do it.

I kind of like that though, because you’re zooming in with each one.

So each iteration is a closer look of what’s out there.

So it kind of makes sense in terms of the progression.

Yeah.

And this is by the way, just what we call the flagship mission.

So NASA always has like this one pinnacle…

It means expensive.

Yeah.

The one with the biggest price tag.

Exactly.

Slip that in there.

That’s so funny.

JWST, because it’s the infrared and because it was conceived to be able to observe the birth of galaxies, which in the early universe emitted ultraviolet, but then red shifted to the infrared in today’s epic.

But the infrared also lets you see inside gas clouds.

So JWST is serving early universe astrophysicists, as well as looking into gas clouds that are sitting in front of our nose.

I ask you, JWST serves many branches of astrophysics, of people who would not otherwise ever be talking to one another in their research projects.

Does this next generation flagship mission also serve people who are studying large scale universe?

Or is it just your people who are studying habitable world?

I think we’ll see, but obviously the primary focus is imaging exoplanets, but that also means it has amazing abilities, for example, to image stuff in the solar system.

And depends whether you call that a separate field, but planetary scientists and exoplanetary scientists actually tend not to talk to each other too much.

On top of that, it will hopefully have ultraviolet capability.

So when you go to the ultraviolet, rather than the infrared, that gives you access to the high energy universe.

Yes, it does.

Like black holes and stuff.

Yeah, good.

So I think in that sense, it will be-

I’m glad to hear that, because one of the great things about JWST is because of how many different branches, how many different subfields within astrophysics it serves.

Correct.

Yeah, as did Hubble.

Yeah, we want this, we want, you’re going to put a mission of this kind of price tag up there.

You want the whole community behind it.

So you can’t just go singly on a single-

Billions price tag.

But the smaller missions are how much?

Oh, maybe $100 million.

$100 million, yeah.

Oh my God.

That’s something Bezos could actually do himself.

Right, a lunch check for that.

Why are we waiting for a commission?

Jeff, we need some money.

That would be nice.

But he likes race, by the way.

Yeah, exactly.

Let’s see, and Scott says, hello, Dr.

Tyson, Dr.

Nice, Dr.

Kipping.

Cinnamon from Roseville, California, here.

My question is about-

Cinnamon?

Cinnamon.

My question is about the-

We had a hamster named Cinnamon.

This is a human being named Cinnamon?

Okay, fine.

Okay, that’s fine.

Oh, who knows?

Maybe this is a hamster right there.

Very smart.

Don’t say that.

I can’t get that out of my head.

A very smart hamster.

Just sit in here and actually, the translation is.

That’s the translation.

Click it up.

A little tiny hamster on the computer.

Okay, go.

My question is about luminous bass, blue optical transients or LFBOTs.

Have astronomers, astrophysicists come to the determination as to what they are?

Is it a supernova, kilonova, intermediate black hole shredding a star?

Also, why do you think that the LFBOTs are so different than others or one particular one, which is AT2002?

First of all, it needs a different name, okay?

Yeah, because that sounds like a 90s boy band.

Yeah, that’s a-

LFBOT, yo, what’s up?

It’s me, Jimmy from LFBOT, girls.

I haven’t heard of these.

Do you know anything about them?

I don’t know a lot about this particular phenomena, to be honest, but I think it’s another, for example, similar to this sort of fast radio bursts, where there’s these very strange observations, which we still don’t really have a good explanation for.

I think it’s just a nice example, I would say, of the fact that there is still a huge amount about the universe that astronomers do not agree about what’s really going on, and that’s interesting.

That’s what’s great.

Yeah, and every new frontier of observations will bring more of these mysterious things into our awareness.

That’s very telling, I like that.

Because you’ll see things as you never…

You didn’t even know!

You didn’t even know to know!

You didn’t even know.

You didn’t even know you didn’t know.

And undoubtedly new questions too.

Exactly.

That’s very cool, very cool.

Richard Hart says, hello fellow astro explorers.

Richard here from Elk Grove, California, my son Kevin Hart.

What?

I’m sorry, I don’t know why that made me laugh.

His name is Richard Hart, his son is Kevin.

Yeah, why not?

My son Kevin Hart wants to know why we’re made of star stuff, okay?

What are the elements that are made in stars?

My daughter also wants to know, her name is Kyrene, if all moons have a frozen core, and does that mean that they have a frozen heart?

Oh, Kyrene bless Kyrene.

And the answer is yes, they hate you.

No, I’m joking, I’m joking, I’m sorry.

Okay, so why are we made of star stuff?

Let me preface that, these cool worlds you’re looking for, can I presume that some of the motivation is there might be places where you’d find life?

Oh yeah, for sure.

That’s one of the main reasons we’re interested.

Otherwise, it’s just an object out there.

Okay, so you then care deeply about the ingredients of life.

Correct, and the search for it, yeah.

So I would just put it like this, there isn’t really that many ways to make heavy metals, heavy, what we call metals, heavy atoms inside your body, inside planets, and stars are the main manufacturing method which the universe creates these things.

So why we star stuff is because there’s basically no other way to make the stuff in your room and in your body without having a star.

It’s all manufactured inside the core of those stars.

Oh, that’s so wonderful.

But that’s a little cop-out-y.

Because he’s saying, of course you’re made of stars.

There’s nothing else we could be made out of.

I mean, that’s an answer, but I…

It depends what you mean by the why.

I mean, that’s how I would interpret that question, the why.

But if you want to know the how, that’s a different question.

Maybe that’s what you’re thinking.

I think that’s the disconnect here.

So, because I was going to say…

I’m how-ing it, you’re whining it.

Exactly, because I was going to say, if all the stuff in the universe is in the star, well, then that’s all we could be made of.

But, how did that stuff get from stars into us is another question.

Gotcha, because if it all stayed in the star, this would be a boring universe.

Right, there’s nothing going on.

Got it, very good.

And so you care that all those same ingredients are on your cool world.

Absolutely, yeah, I mean, what we’re hoping is to detect those molecules in exoplanet atmospheres, which would be our first hint of complex chemistry and life potentially in those planets.

We don’t know that all moons have a frozen core, because we only know about the moons in our own solar system.

What about the moons out there in the rest of the universe?

And then you’ve got moons like Io, which are being actively squished and squashed due to the gravity in the tidal field.

From around Jupiter, exactly.

So it’s not obvious that Io would have a frozen core either because of all the tidal deformation is going on.

And we know it certainly has volcanism.

So it must have some layer of magma underneath its surface.

But would any moon have a frozen core if it collapsed from something bigger?

Doesn’t it get hotter in the middle?

So wouldn’t everything be…

But over time, it will cool.

It could cool to just being a rock floating and frozen and that’s it.

But you’re saying most things then would have a warm core?

Maybe.

Oh, so everything’s like a medium rare steak.

Right, I’d say so.

It’s got a warm pink center.

But go far enough into the future and everything will be frozen.

Well, they…

Oh, oh, right, far enough.

Thank you for that very bleak album.

That’s what I’m here for.

The world will not end in fire, but in ice.

Oh, boy.

Chuck, just one more question.

Oh, right, here we go.

He says, this is Andrew O.

Hello, Dr.

T, Dr.

K and Chuck.

Okay, we just know you’re Lord Chuck.

Yeah, exactly, but I like it.

He says, how common is it for planets to have atypical rotations?

Do they always occur?

Atypical, like not typical?

As in atypical, as in not, right, atypical.

Do they always occur due to external forces?

And it happened to other astronomical bodies?

Have we observed a planet that rotates in the same odd manner as Uranus, but in the opposite direction?

Ooh, maybe they’re also referencing the orbit.

But there’s rotation and revolution.

Revolution and rotation.

Right, counter-rotating and counter-revolving.

If they exist, they should be showing up in your data.

Yeah, so in terms of the orbit, yes, we can measure that.

We can tell if it’s going backwards around its star.

And there are some cases.

We use this effect called the Ross-to-McGlocken effect that essentially looks at the redshift and blueshift of patches of the surface of the star as the planet passes in front of it.

Using this effect, you can actually tell which way the planet is going over the face of the star by looking at those little shifts.

So that’s pretty cool.

And we have seen some planets going backwards.

On Astral People Clever, we got the cleverest people using just light.

And I keep getting blown away by how much, it’s like either, he can’t go out there and manipulate it.

He can’t put it in a Petri dish.

He can’t just tilt it in another direction.

He’s gotta sit there and wait for the light.

Whatever the data from the light is, that’s it.

And you know what kills me, it’s like I look at this and I’m like, you people are the most resourceful people ever or you are just making this crap up.

It feels a bit like being Sherlock Holmes is the analogy I like.

We have these clues and we have to think really hard about un-piecing what’s going on.

So with the rotation in terms of orbit, we can get that.

The rotation in terms of the actual planet spin, we can’t measure that.

There’s only been measured, I think, for one planet and that’s Beta Pictoris B and that’s a directly image planet.

And in that case, it looked kind of normal, but that’s the only example we have.

So it’s actually something we’re working really hard in the future of these new telescopes to try and measure.

So Beta Pictoris B.

So Beta is the Greek sequence of the lettered stars.

And for many constellations, it’s lettered in sequence of brightest to dimest.

So there’d be Alpha Pictoris and then Beta Pictoris, which would ostensibly be the second brightest to star.

Pictoris is the genitive form of Pictor, which is a painter’s easel.

That’s a constellation, a painter’s easel.

And then your Roman letter was what?

B.

B, lowercase b.

And?

That’s the first planet discovered.

The first planet discovered around it.

And A, you give to the star itself.

Okay.

And so who’s got the most planets out there?

That would be the Bob Ross constellation.

Which is in front of the pit tour.

I think the record is a Trappist.

Trappist 1 is a very famous star system that has seven, sometimes called the seven dwarfs.

They’re all such small rocky planets.

I think there is another star that has eight planets that’s been discovered, but that’s just what we know of.

So there surely are even more.

You know what would make headlines?

If he discovers one that has nine planets, the Pluto people will rise up again.

We want to keep them tamped down.

That’s wild.

Well, let me reflect on this briefly and then we call it quits, all right?

So every generation of telescopes, we’re trying to answer questions that we’ve posed.

But you know what happens?

Those questions and our attempts to answer them take us up to the limits of what that telescope can deliver.

And those are the seeds for a next layer of creative thinking about what science can be discovered and what new tools and technology may be necessary to discover it.

At any given moment, we have smart people and great technology trying to figure out how this world works.

But there comes a time where the technology can only take you so far.

Maybe there are questions you had but remained unanswered because you are awaiting a next generation of technologies to get you there.

And maybe you are awaiting more than that.

Maybe you are awaiting a next generation of thinkers, students you have trained that will come after you and carry on questions that you’ve begun.

Or better yet, maybe with new technologies, new science, new ways of thinking, there are questions you will ask that you didn’t even know to pose.

So when I think of David Kipping’s efforts with the James Webb Space Telescope, there’s some questions he couldn’t answer with previous technology.

He tried, couldn’t answer.

Now, they’re flowing.

But what happens next?

He sees things that are at the edge of what this technology can deliver.

And now he’s looking to the horizon, is there another kind of telescope that can hone in on these unanswered questions?

And maybe that’ll take me there.

And you step back and you see this exercise and you say, that’s how science works.

One idea builds on another.

One bit of technology surpasses what came before it, enabling you to answer questions you have posed and to pose questions you never thought to ask.

I wouldn’t have it any other way.

That is a cosmic perspective.

Thank you for being on StarTalk, dude.

And you just ride up the street.

You know, if you discover life, you’re going to give us a call?

You’ll be on the phone first person.

Call me.

You’ll be the 27th person like that?

No, it wouldn’t be Little Green Men necessarily, but you might discover something in the atmosphere using the JWST data.

We want to hear about it, because that will make headlines, and we want to be there right with you.

Okay, he wants to put on his own podcast first, then is on his YouTube channel, and then on the thing.

Then maybe world news.

Then he wants to call his mother.

He’s going to call his mother.

Then call us, okay?

We’ll be fifth to know.

All right, this has been StarTalk Cosmic Queries with my friend and colleague, David Kipping, right up there at Columbia University, an Ivy League school right here in Manhattan, in the middle of the city.

Chuck, always good to have you, man.

Always a pleasure.

All right, this has been StarTalk.

Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron