About This Episode

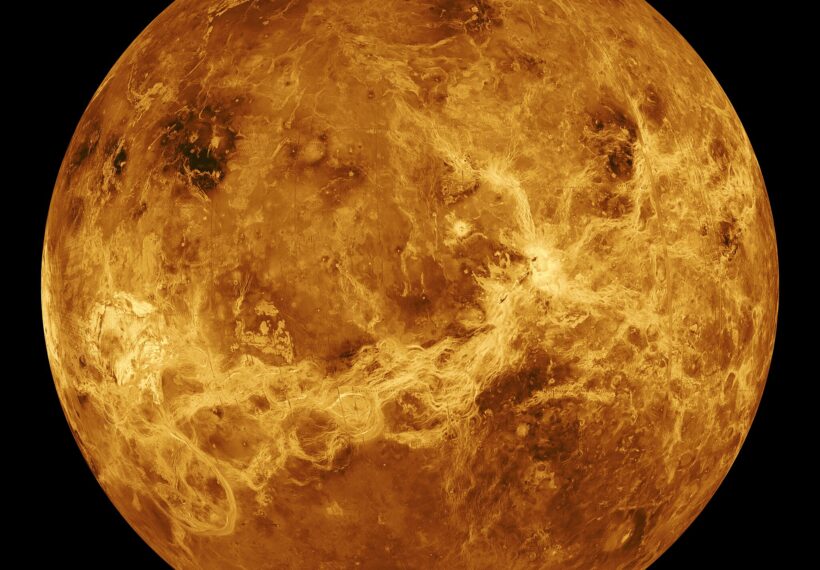

Is there life in the Venusian Clouds? Neil deGrasse Tyson and comic co-host Chuck Nice are joined by planetary astrobiologist David Grinspoon to discuss NASA’s return to Venus, our space future, and whether we’ll find life in our solar system.

As a primary investigator on the upcoming DAVINCI mission, David explains why we haven’t sent a dedicated U.S. mission to our sister planet since the 1980s and how the history of “space futures” has always been a reflection of our own culture and politics. Neil and David explore the evolution of our planetary visions, from the mass delusion of Martian canals and Jules Verne’s moon voyagers to the propaganda efforts during and before the Apollo era. You’ll learn how people once assumed every planet was inhabited, only to have their “cloud swamp” dreams shattered by the harsh reality of a runaway greenhouse effect.

When did scientists realize Venus’s runaway greenhouse and that it wouldn’t have life? We get into the nuts and bolts of the DAVINCI (2031) and VERITAS missions. How do you build a probe to survive pressures 100 times that of Earth and temperatures hotter than a pizza oven? David breaks down the dive through the Venusian atmosphere, where the mission will capture the first-ever 21st-century measurements and descent photography of the surface. They also tackle the phosphine controversy: Could life actually thrive in a permanent global cloud deck? Why isn’t there life in the clouds on Earth, even though you can find life everywhere else?

With the Europa Clipper heading to Jupiter’s icy moon and the OSIRIS-REX sample from Bennu revealing 14 different amino acids, the kit for life seems to be sprinkled across the cosmos. If the ingredients are common could life itself be too?

Thanks to our Patrons Nick Pullia, Sean Cater, Keith Reiss, Seph Gordon, Charlie Viola, Miguel Rangel, Andrew Ferguson, JeAnnette Elaine Thomas, Hugh Caley, Daniel Weber, Chris, Peter Grossman, Darryl Baker, Joyce A Edwards, Maxim, Joshua Richard, Patrick ridlon, Kathleen Reardon, David Watts, Angelina Bryant, Liza, Dave Holloway, Ricardo Andrés Morales Muñoz, Damian Wilson, m. szachacz, Vince Johnson, Lucy, Randal Walcott, Rachel Ambrose, andrew wong, Richard Hudson, Peter Galindo, Mehdi Degryse, Carl Starr M.D., Rodrigo De Luca Comelli, Christian Harris, Ryan Grillo, Jose Villavicencio, Kell, Russ, Mota Ephrahim, Andre Campos-Gomez, Catherine Noiboonsook, Sam McClure, Jerry Taylor, Ian Howarth, Gerrard Lobo, Jordan Strauch, Pretender to the Throne, Dustin, Bulbacats, Jim Mirra, Matt, Adrian Martinez, GuruMojo – Kenny, Malcolm Townes, Russell, Vincent Thomas, Caleb Winters, Carsten, Frank, Andrew Sabado, Roger beeper, Jason Burden, lilacjasminetea, Eric, Samantha, Eric Sneddon, philip griffiths, Christian Chidester, Bruce Berky, Bill Polskoy, Maddux Hammer, Tim Neumark, nathan burcl, Paul Santos, Tognia, sugar, Mike Vacay, Niklas lundkvist, JaneB, Gutek, Natalie & Dad, Ashley, J Sh-Wood, Alexej Muehlberg, and Emery for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTChuck, we’re going back to Venus.

Haven’t been there in like 50 years.

You know what?

I haven’t been at all and don’t ever want to go.

Coming up.

What’s on the docket for NASA and the search for life in the solar system with the one and only Dr.

Funky Spoon on StarTalk.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk, Neil deGrasse Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist.

And right to my right, Chuck Nice.

What’s up, Neil?

All right.

Yeah, man.

So, one of my favorite subjects today is going to be astrobiology.

Oh.

Oh.

But not only that, we’re going to take some extra twists on it because we’re bringing in the one, the only.

Drum roll, please.

David Grinspoon.

David Grinspoon, welcome back to StarTalk.

This is your, like, 20th time on StarTalk.

Something like that.

Hey, yeah, it’s great to see you guys, as always.

Great to be here.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Let me get your resume updated here.

A professor at Georgetown University.

You’re based in Washington, DC area.

You’re on the board of the Scientific Society for Astrobiology.

That’s a new one for me.

Advisory Board of the SETI Institute.

They can’t do much better than you on that one.

And on the science team of NASA’s upcoming Da Vinci Mission to Venus.

Now you wrote a book on Venus, but was it the book on Venus?

Well, I like to think it was.

That was a few years back.

What was the title of that book?

Venus Revealed.

Yeah.

Okay.

Sounds very sexy.

I know it does.

Sounds very, very sexy.

I wrote it right after the last US mission to Venus, which is, you know, embarrassingly long ago, except it’s amazing that, you know, since the 1980s, we have not had a US mission to Venus, but we’re trying to change that now.

So maybe I’ll have to write another one.

So the more fully in this episode, we want to probe your thinking of late and the history of space futures.

Oh, that’s an interesting thing.

It’s your children, Monty!

Your children!

You know, in that scene, why were they rushing if they have a time machine?

Yeah.

Hurry up!

Hurry up!

We’ve got to get to a point in time that’s already passed!

It seems like time would be the one thing you wouldn’t have to worry about.

That’s a pretty good observation.

So, this history of space futures, that seems like it’s intimately intertwined with politics, with culture, with funding, with dream states, even with movies that might try to shape our visions.

As, for example, 2001, A Space Odyssey, that got everybody ready for the future that actually never came.

Exactly.

That was the one that really, you know, when I was a kid, it was 2001.

That was the future that was going to come to pass.

I’m still waiting for it.

One future from 2001 Space Odyssey has come to pass, and that’s artificial intelligence, because that was HAL.

He was, you know, an AI.

And HAL was homicidal.

And some are the ones from Google.

I’m sorry.

Are they a sponsor?

I take that back.

They’re great.

So, how long have you been at Georgetown?

Well, I’ve taught there before, and then I was sort of adjunct, but not really active, because I was doing other things, and I was at NASA.

But I’m returning there to teach just starting this upcoming spring semester.

And that’s the title of your course, right?

Yeah, yeah.

Well, I think it’s Justifying Space, and then the subtitle is, you know, A History of Space Futures.

Okay.

But it’s a fun lens to look at the history and the present of space exploration, because it’s not quite just asking what happened.

It’s what were people thinking?

What was the motivating vision?

What future did they think they were creating?

So, you know, you can go all the way back to HG Wells and Jules Verne and those kinds of images, and then up to, you know, Verne von Braun and Robert Goddard and, you know, sort of start of Rocketry and Apollo and, you know, all these, like, inspiring visionaries like Carl Sagan.

You know, what kind of future were they helping people imagine was going to come to pass through space exploration?

And then you can take it right up to the present.

Carl Sagan, who you knew very well.

Yeah, big influence.

Right, right.

So when you were a kid…

Wait, we buried the lead.

How did you know Carl Sagan?

Oh, man, I grew up with…

He and my dad were best friends, actually.

Sagan and my dad, they were both Harvard professors.

Oh, my God, I didn’t know.

And before Sagan went to Cornell, because he was denied tenure at Harvard.

But believe it or not…

Take that, Harvard.

Yeah.

You effed up, Harvard.

Everybody’s been saying that ever since.

Yeah.

Yeah, so, okay.

Yeah, so he was kind of in the household when I was, you know, six years old, he was Uncle Carl, and kind of just around as I was growing up, which was pretty interesting in a lot of levels.

So for one thing, he wasn’t famous when I first met him, when we first knew him.

And so seeing that whole phenomenon happen to somebody that you knew well was pretty interesting.

Well, wait, that could have been interpreted another way.

He wasn’t famous until he knew me.

Oh, no, I was not implying a causal relationship there.

He didn’t put the cause and effect in there.

And so tell me, were you, what were your, because I want to hear from Chuck as well, and I got my own views here.

Were you primarily influenced by the dreams of people you knew, by storylines in movies, by books you read, or by what you knew the government was attempting to do in the space race?

That, you know, I hate to say it, but all of the above.

Like, you know, like so many space scientists of my generation, I have to say that the Apollo moon landings were formative.

Like, I was in fourth grade and we got, we saw the people walking on the moon and it was amazing.

And then I became, probably as a result of that, a space and science fiction geek.

When you’re 11 years old and you’re reading all the science fiction and watching the first actual human ventures into space, you don’t necessarily differentiate.

It’s all just like space in the future is cool.

So and then plus, obviously, I had some people in my life that I knew that were involved in space exploration, which was a big influence.

So it was kind of all of the above.

It was just in the air, science fiction, and what was happening in real life, and what people I knew were involved in.

And it was just clear to me that space was where it was at, and that was the future, and that was what I wanted to be part of.

You’ve got firsthand DNA for this curriculum of this class that you’re teaching.

Wow.

Look at that.

How about you?

My biggest influence, I’m terribly sorry to say, was not education or Carl Sagan.

It was Star Trek.

When I was-

Don’t apologize for that.

Yeah, when I was a kid, Star Trek came, it wasn’t even on TV anymore.

It was on UHF channels.

And so when I-

Wow, grandpa.

What was UHF?

UHF?

What?

Yeah.

Do you know what it stands for, UHF?

Let me think.

Ultra-high-frequency?

There you go.

There you go.

And you know what VHF stands for?

Very high-frequency.

Okay.

Get out.

Somebody dropped the ball there.

Yeah.

Okay.

But my reward for-

I would come home and watch cartoons because my parents weren’t home.

But then I knew I had to start my homework by four o’clock, no matter what, because if I wasn’t doing homework or if it wasn’t mostly done by the time I got home, there were consequences to be had.

So then as a reward for when I finished my homework, Star Trek would be on and because it was not like on regular TV, it came on every day and then I found my-

Those are called reruns.

Yes.

Okay.

So I watched it every single day and I was like, oh wow, I guess I reached the end because they’re coming on over again.

You saw reruns.

Okay.

Because it was only-

It was repeating.

Yeah.

I mean, I don’t know how many episodes there were because there weren’t a lot.

Three seasons.

Three seasons?

Yes.

At all?

That’s all.

Well, it was canceled after three seasons.

Right.

So in a year, you could see everything, in less than a year, you could see every single episode.

In retrospect, canceling Star Trek is like not giving tenure to Carl Sagan.

You did what?

You did what?

Yeah.

Anyway, so here, let me not bore you with the details.

What it did for me was they would say things like plasma conduit, light speed, phaser.

So vocabulary descended upon you.

Vocabulary.

I was like, what the…

I honestly didn’t…

I wanted to understand what they were saying.

I wanted to be like a crew member on the…

I didn’t want to just sit there and watch.

I wanted to understand.

So I started looking at all this crap up.

And honestly, that’s when I first got like excited about science and about space travel and the whole deal.

All from this stupid TV show.

So Chuck, then can you explain to me like how dilithium crystals work?

But I can’t explain to you, but I can tell you this.

They’ll never hold up more than, sir.

They’ll never hold up.

The dilithium crystals will dissolve, sir.

So yeah, the dilithium crystals was great.

I also love the fact that they put all that kind of little stuff in there, which is absolute nonsense, but they somehow married it to some form of science to make it work.

This is the creativity on the frontier.

It’s just to flesh out what’s going on.

And so have you ever seen the periodic table of fictional elements?

No.

Dilithium is on there.

Awesome!

I love it.

Unobtanium.

Unobtanium is there.

Vibranium is on there.

Vibranium is definitely there.

It’s a very cool list.

Oh, I gotta look that up.

How did you guys feel about the portrayal of aliens?

In Star Trek?

The astrobiology of this, yeah.

There’s obviously a range.

And Star Trek, I mean, in a lot of ways, Star Trek holds up really well.

It was very sophisticated, high-quality entertainment for some of the reasons Chuck just mentioned.

And it’s amazing how much it’s still referred to, even amongst professional astrobiologists.

We get into conversations, well, could you have something like a Class M planet?

But obviously, they’re devices which are just devices which have no correlation to any science.

And I have to interject there.

They classified planets better than we ever did even today.

Wow.

Right.

Right, right.

They classified them by whether they could sustain life, by whether they were, you know, rocky, gaseous.

To us, a gaseous, a rocky, or one that sustains life, they’re all just planets.

So if you just say, I discovered a planet, you have to play 20 questions to know what kind of planet was discovered.

So this was my sympathy for the Pluto folk out there, because to remove it from the ranks of planets, when what should have happened is that we should have nuanced the word planet with many more adjectives, descriptive adjectives, for gas planet, rocky planet, dwarf planet.

You just go down the list.

You know, we’re still in the infancy of our understanding of planets.

And you know, they’re from the 23rd century, so it makes sense they would know more importantly.

But, you know, I mean, at the time of Star Trek, of course, we hadn’t even discovered any exoplanets.

And so we had no real diversity to work with.

Now we at least are starting to understand.

It would be another 30 years before we discover our first exoplanet.

So we’re starting to understand the diversity of planets, but we’re still pretty naive.

But, you know, as far as aliens, the problem with Star Trek aliens is they’re, you know, generally humans with prosthesis.

And that makes sense for the economics of producing a TV show.

But they don’t generally look like what we would picture aliens to look like.

Of course, we have no idea what aliens look like.

But we imagine probably they don’t look just like humans because of the randomness of evolution.

And so I have a book behind me, which is called Visions of Space Flight, which is a modern book, but goes back 40, 50, even 60 years to show how people were dreaming this up.

Is any of that infused in your class?

Just where we got it all wrong?

Yeah, no, a lot of that is in there.

And there’s so much fun material to work with.

There’s like those famous Collier’s articles, Collier’s Magazine that Von Braun did with Walt Disney, and Chesley Bonestell, you know, there’s so much.

So remind us who all these people are.

So Werner Von Braun, give us a three sentence bio.

I just mixed two different things up.

But so Werner Von Braun, of course, was the former Nazi rocket scientist who invented basically the V2 in World War II and then came over with a bunch of other German scientists and was very instrumental in designing the Saturn V and getting us to the moon, the Apollo program.

Well, he said to you, he’s just, they came over.

No, we grabbed them.

Yeah, but I didn’t know how much we should go into Operation Paperclip.

Yes, that’s what that was.

Yes, because we didn’t want them going to the Russians afterwards.

The Russians and Americans divided Germany.

Right, right, okay.

So we bring them, I’m intrigued that we bring them and put them in Huntsville, Alabama, which is like-

Makes sense.

That’s a place where you would put some Nazis.

Alabama is the place, if you got to relocate some Nazis, I’m pretty sure you wouldn’t do a bad thing by putting them in Alabama.

Don’t put them in Detroit.

You damn sure better not put them in Chicago.

What is this?

So many Schwarzes!

The space program would have never happened.

So, anyhow, so he goes to Alabama, and that’s Huntsville, Alabama, where he births our presence in space.

Because you didn’t say this, but I have to add, the V2 rocket was the first rocket to leave our atmosphere.

And everybody knew that if there was any future in space, it’s going to be through the technologies that enabled that rocket.

Okay, so you got more on Von Braun?

Well, he was also a proselytizer for space and a major popularizer.

And so he got together with Walt Disney, and they did these kind of propaganda films, but all about the great future of man in space.

Of course, it was man in space then, it wasn’t humans.

And then they also did this series of articles with Chesley Bonestell, who was almost like the original space artist, or the guy that did the first very scientifically accurate and careful space art.

And he and Von Braun teamed up for the series of articles in Colliery’s magazine, I guess in the late 40s or early 50s.

No, no, in the 50s, early 50s.

In the 50s, thank you.

They’re really fun to look at, because it’s all our future in space.

And very imaginative and very evocative.

And I think it really did help along with other efforts to kind of prepare the populace for thinking about space as this aperture to this wonderful future.

And you know where the first of those meetings were?

No.

At the Hayden Planetarium.

Get out.

Oh, yeah.

Wow.

Yeah.

Impressive.

Yeah.

And so others would happen sort of offline, but the original ones.

But it was not only the Chesley Bonestell.

They also had journalists there and other people who could sort of help spread the love.

And like you said, it was a little bit of propaganda, getting people ready for the future in space.

I love it.

But we need more of that today.

I’m serious.

It’s like one of my biggest complaints about science today is that we don’t propagandize.

We need better advertising.

That’s what you want there.

And we have an installment of StarTalk where we toured Paul Allen’s collection of space art, which was heavily represented by Chesley Bonestell art.

And so we went to the Christie’s.

They gave us access to the back of house.

And so, yeah, find that in our archives.

That was a fun little tour we took.

Oh, cool.

So tell me, I don’t remember them showing aliens in any of those illustrations.

So it was just we as explorers.

Yeah, no, that’s right.

There was nothing, I don’t remember anything in those sort of Disney films he did or the Colliery’s Magazine, that kind of stuff about extraterrestrial life.

It was more just like humans are going to go to space and there’ll be new places to live and new resources and new places to explore.

And he talked about the national security implications, you know, of course, America has to dominate the space because we can put nuclear weapons up there and make sure that the world is peaceful and American.

You know, it was kind of infused like that.

The harder I pull the bow, the safer I feel.

Nice.

As we aim, arrows to each other, the harder we each pull, the safer we feel.

Yeah, so of course, there is speculation about alien life going back in some of the other future literature of the past, but not in this sort of Apollo propaganda stuff that we’re talking about.

So let’s go back in time 120 years or so, or even a little earlier, and we get to Jules Verne from Earth to the Moon, and he gives how many hours it takes, and he comes pretty close.

Wow.

Yeah, I don’t know how he figured that out.

Earth to the Moon in like 96 hours or something, which is a little longer than it actually takes, but it’s close enough, you know.

In the ballpark.

I mean, really good, yeah.

What intrigues me is that if you go far enough back, before we knew anything about the Moon or anywhere, everybody presumed that since Earth is a planet and we have life, that every other planet would have life.

And so from Earth to the Moon portrayed moon beings.

And no one is wondering, well, can they breathe the non-air?

Do they, you know, no one is asking that question.

And so just the fact that we are a planet and have life opened the floodgates for imagining every other planet to have life.

When did planetary scientists discover that Venus has a runaway greenhouse and you’re not going to imagine life thriving there?

Yeah, it’s pretty recent, really.

It wasn’t until people started to wonder in the 50s because they saw this excess microwave radiation they couldn’t explain and they thought, well, could that be from a super hot surface that with, you know, with basically the advent of radio astronomy after World War II that made that possible.

But it wasn’t until the first mission to Venus, which was Mariner 2 in 1961, that it was demonstrated that Venus was hot and definitely unearth like.

So throughout the whole time of really the 20th century up until the space age, there was a lot of speculation that Venus was probably pretty earth-like.

A lot of scientists thought that and could have life.

Well, it’s approximately the same size as Earth.

It has the same surface gravity, a little closer to the sun.

So it’s a little hotter.

That wouldn’t hurt anybody.

Yeah.

And it’s completely covered with clouds.

And so they deduced that correctly.

They said, oh, it’s covered with clouds.

And well, what are clouds made out of?

Water.

So therefore, it’s probably a swamp planet.

And that was what people thought it was.

Yeah.

Now, what about Mars?

Wasn’t there a point where they thought Mars was a thriving society?

The canals.

You’re talking about the Mars canals.

And they thought, well, they had to be made by someone.

Because nature makes channels.

Humans make canals.

Yes.

Right.

That makes sense.

Yeah.

So they thought they saw all these linear features, which couldn’t possibly be natural because there are all these straight lines going across Mars.

Of course, Percival Lowell popularized this, and he was a very persuasive guy around the turn of the beginning of the 20th century.

And he was so persuasive that a lot of other people saw the canals too.

They were like, oh, yeah, we see them.

And it took years to realize that the canals weren’t there, basically from close appearances of Mars and better telescopes and cameras.

But the interesting thing is that even after the canals went away, the idea of life on Mars sort of scientifically supported did not go away.

And people thought there was evidence for vegetation.

Mars’ surface changes with basically what we now know are seasonal patterns of windblown dust.

But you see these changes in color and brightness, and they thought, oh, that’s seasonal vegetation patterns.

And then even in the late 1950s, there was an observation of chlorophyll in the atmosphere of Mars.

It was published in Science Magazine.

Turned out to be wrong.

But there was so much wishful thinking that people would say, aha, there is plant life on Mars.

And again, it was pretty recent.

It was really once we started going there with spacecraft that these visions kind of vanished in favor of the more realistic, very alien conditions that you find on these planets.

And just to be clear, the older you get, the more recent, the 1960s.

Oh, yeah, that was just yesterday.

I’m just saying, well, 60 years ago, recent to you.

Because 60 years before that was the year 1900.

Oh, my God.

Okay.

So, but it was so much believed so widely that that’s how Orson Welles was able to pull off the radio broadcast that put everybody into a panic.

Wait, wait, so no, but it’s before that because it was Percival Lowell’s published work on Mars and its canals that spawned War of the World to be written in the first place.

War of the World was written right after that got published.

Within five years, HG.

Wells wrote War of the World because canals on Mars, that’s headlines.

In 1895, that’s headlines.

And so HG.

Wells writes it and these are like evil aliens from Mars sucking our brains out.

Then we still have 30 years whenever the radio broadcast, which is based on HG.

Wells’ story.

People confuse HG.

Wells and Orson Welles.

Orson Welles, right.

No, no relationship.

Orson did the radio broadcast.

The radio broadcast and he did it on Halloween Eve.

Right.

And not Halloween though, but the eve of Halloween.

Right, Mischief Night.

Take it?

Mischief Night.

Oh, is that right?

Makes sense.

Okay, okay.

Makes sense.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

And so everyone’s primed for this.

Yeah.

And I think that might have been the first evil alien trope.

Yeah, well, you know, the other thing that HG.

Wells was really influenced by, definitely Percival Lowell, but also the recent stories he had heard about the Tasmanians basically being wiped out by Europeans from Australia.

He mentions that in his book.

Oh, yeah.

What had happened when a quote, you know, technologically superior civilization encounters a quote, more primitive civilization, and it’s not good for the for the for the for the lesson, you know, and and and so that also led to this trope of the evil invading superior aliens that you know, that you don’t stand a chance against.

Yeah, but no, you missed a point there.

Very true.

But there’s a nuance, which is in his book, he’s trying to justify why these Martians wanted to kill us all.

And he said, should you be surprised by this, given that we exhibit that same behavior to ourselves?

Wow, that’s a great point.

This is the point, you got no argument, how are you gonna come out of that?

Exactly.

You got no way to come out of that argument.

So David, I didn’t know that others also saw the canals, but if they did, that’s a form of a mass delusion, because Percival Lowell has like the best telescope, and he’s rich, and he’s got on the mountaintop, he’s got great observing conditions, he sees it, you don’t want to not see it, because how could you not, if you don’t see it with your crappier telescope, you’re not in the books, right?

So if they really are there, and you did see it, second, you still get talked about, right?

So.

Yeah, no, it’s funny, there is a literature of other people mapping the canals and saying, well, Lowell’s position for this one is just a little bit off, it’s really over here.

And it’s a complete delusion, and this is because nobody has photography yet.

So they think, there’s not a, let’s look at the photograph.

It’s everyone’s eyewitness testimony of what they think they see.

Wow.

Yeah, so this is evidence of the susceptibility of even scientists to the power of suggestion, the power of your own bias.

And Leonardo.

Yes.

Once said.

Go ahead.

The greatest deception men suffer is of their own opinions.

Yes.

Oh, that’s that’s gosh.

He knew this.

Yeah.

Well, that’s why he was so brilliant.

Yeah.

It was like, I will not even fall prey to me.

Yeah, that’s beautiful.

Yes.

Give me give me give me give me somebody.

Well, that was his opinion.

So, David, that’s a perfect segue to this DaVinci mission.

Please catch us up on what’s going on.

We’re finally going back to Venus.

Yes.

Yes.

It’s been a long journey for already.

We haven’t even left the ground.

But for those of us who’ve been advocating and agitating for new Venus missions.

And the good news is that we have several Venus missions, two American missions, DaVinci and Veritas, which is an orbiter, which very much complements DaVinci, which is an entry probe that descends down through the atmosphere to the surface.

And then there’s also a European mission and an Indian space agency potential mission.

So a lot of agencies are getting into the game now.

But the one I’m most excited about, because I’m on the team and very involved with, is this DaVinci mission, which if all goes well, will launch in the 2031 timeframe now.

As you probably have heard, NASA’s had a little bit of turmoil with the budget.

You think?

A little bit.

Didn’t you used to have a job with NASA?

Oh, yes, until fairly recently, I was the Senior Scientist for Astrobiology Strategy at NASA.

Yeah, okay.

Totally useless.

Yeah.

What a hoax.

A terrible hoax.

I’ll tell you what we need.

If I still had that job, I wouldn’t be able to talk to you about some of the things I can talk to you about now.

Should have kept them on.

I like loyalty and hate.

I’m free.

But yeah, I’m still very fond of and close to NASA and working with NASA on a lot of projects.

I no longer am a NASA employee at the moment.

But DaVinci is very much a NASA mission, which is still moving forward and being built.

You know, there’s some question, as with a lot of projects right now, about the future schedule and viability.

But right now, nobody’s told us, it’s not happening.

And we’re pretty optimistic about, you know, we know that Congress is very supportive of maintaining this mission.

A lot of it’s built.

We have an entry sphere.

And some of the instruments are already built.

And you know, it’s a very challenging engineering problem to drop something into that intense environment of the Venus atmosphere and have it survive to the surface.

Quantify intense.

OK, well, in the upper clouds where the mission starts, we drop it into the atmosphere in a parachute.

And in the upper clouds where it starts to operate, it’s actually more or less the same temperature and pressure as the surface of Earth, like in the room you’re sitting in now.

That’s sort of the middle upper clouds of Venus.

But as you drop down, it gets hotter and hotter to the point and higher and higher pressure to the point where when you reach the surface, it’s 900 degrees hotter than the hottest self-cleaning temperature on your oven.

Fair enough.

And it’s almost 100 times the surface pressure of Earth.

So crushing pressure, searing temperature.

And by the way, those clouds you drop through are made out of concentrated sulfuric acid, like battery acid.

So you have to be able to withstand all these crazy environmental factors.

And we know how to do it.

You know, this thing is well engineered, but it has to be done very carefully, and you have to use some expensive materials.

So the data you’re collecting, is it atmospheric data, or are you going to do stuff when you get to the surface as well?

Both.

A lot of the important part of this mission is involving measurements of the atmosphere that have never been made before.

Because again, we haven’t been able to operate that much in the Venus atmosphere because it’s so forbidding.

So we’ve never had modern instrumentation, never had 21st century instruments that can really tell us exactly what those gases are made out of, exactly what the isotopes are of hydrogen, and what the rare gases are, all these things that really can be diagnostic of the history of the planet.

We’ve never measured them well.

And the radiation going down.

But we’re also going to do really cool things with the surface.

We have an imaging system where we do the first ever descent photography, like really high-resolution stereo descent photography of this very mountainous area where we’re going to land.

It’s always cool when you can see the ground come closer and closer.

Yeah, you’ve seen those famous images from like the ranger program of the moon, right?

Where they get closer and closer and closer and then the thing crashes.

We’re going to do that for Venus, except again with 21st century cameras.

And it’s never been seen before.

And this is going to be a very dramatic mountainous region with really cool and revealing topography, not just in the visual wavelengths, but also in the infrared.

So we’ll be able to tell what the minerals are there.

But you’re not going to crash?

Well, we are going to crash.

You are?

Oh, wow.

Okay.

Yes.

You are going to crash?

Well, we’re going to reach the surface.

We don’t use that word.

We don’t use the term crash, yeah.

We use euphemisms.

But in fact, we’re not designed to operate on the surface, although it’s possible.

In other words, the mission will be considered a success if we reach the surface, but we could survive for a while.

It’s very similar to, you remember the Huygens probe on Titan, where it was only designed, if it reached the surface, it would have been considered a success, but it lasted for another 45 minutes on the surface and did some really cool stuff.

So, we have the opportunity to do that, but if we actually make it to the surface, then we’ve satisfied all of our…

I don’t understand something.

Yeah.

Venus has gravity.

You drop it into the atmosphere, it’s going to reach the surface.

What do you mean, if it reaches the surface?

Oh, sorry.

If it’s functioning.

Oh, okay.

Thank you.

If it’s talking to us.

Yeah, gotcha.

Well, if you need more money to be put in the budget, all you have to do is name the project, the Donald J.

Trump Venusian Ballroom Construction Project.

There you go.

Yeah, but solid gold does not survive at those temperatures.

Just one, if I add a geopolitical comment here, you mentioned that India also has Venus on its sites.

ISRO, so Indian Space Research Organization.

And the United States does not want to be left out of where people are going in the solar system.

So it’s easier for us to declare we want to go somewhere if other countries are going to.

So it’s the space race all over again.

It’s always about that.

Right, it’s always about that.

So, I wouldn’t put it past our motivations to realize that the list of other interested parties added a little flame under our rear end to try to go.

Yeah, and I wouldn’t put it past me and my colleagues to remind our representatives that like, oh, by the way, our competitors are doing this, so we better not mess with our budgets.

Right, right.

And on a non-geopolitical note, just a political note, you know, people could stop voting for representatives who want to give tax cuts to billionaires instead of funding the stuff that will advance us as not only a nation, but as a species.

I mean, that’s just a thought.

You can just hang on to that thought, if you want.

This has been a public service, now.

Comedians against billionaires.

What can I say?

We will never meet a comedian billionaire, that is for sure.

So, we remember from a few years back the assertion that there were, what was the molecule in Venus’ atmosphere that may be evidence for life thriving within the atmosphere.

What?

Will you be, it was phosphines, I think they were.

And we had you on to talk about that result.

Yeah.

Go dig that out of our archives, those of you who are archived dumpster divers.

Right.

But how much credence is given to the idea that life could be completely thriving within an atmosphere and not require a surface at all?

Well, there’s a range of opinions about that.

And I’ve been a proponent of that we have to keep an open mind about that.

There are people who will point out, one of my colleagues, Chris McKay, at NASA Ames Research Center, a great astrobiologist.

We love Chris McKay.

Yeah.

And Chris doesn’t agree with me about the prospects for life on Venus.

And what he says is like, why aren’t the clouds green?

Meaning on Earth.

If you could have life in the clouds so easily, then why aren’t the clouds green?

And that’s an interesting objection, but it may be that there’s some characteristics of the Venusian clouds that are more suitable for life than Earth clouds.

But if they were green, it would mean some chlorophyll photosynthesizing life.

Well, I mean, his point is that life is so opportunistic that anywhere on Earth where you can have life, it’s abundant.

You do, yes.

So why are our clouds full of life if you can have life in clouds?

Didn’t you just give the answer to that when you said life is opportunistic, which means if it’s easier not to have life in the clouds here, then the life will take advantage of the opportunity that’s available, which is life everywhere else.

But if there were no other choice, then perhaps life would manifest itself in the clouds.

No, that’s not how life works.

You don’t think?

No.

Life goes everywhere.

It could possibly go.

Anyplace it could possibly work.

Yeah, because you always want to find some niche where your predators can’t get to.

There’s a lot of pressure to just live in new places if you can.

So then in that…

We have life forms living at the bottom of the ocean where there’s hot vents coming out.

Yes, and sulfur and all kinds of terrible stuff from volcanic.

And they’re doing the backstroke.

And they’re chilling down there.

They’re just chilling.

So in that case…

Actually, they’re hot.

Yes.

So then what would happen in Venus that would be the difference where life could exist?

Would the pressure create some kind of difference or…

Well, one difference is that on Earth, clouds are not a very stable environment.

They don’t last.

They come and go.

They evaporate.

They literally dissipate.

They’re very thin-gathering in the water vapor.

Venus is covered with a permanent global cloud deck.

So the clouds of Venus are almost like the oceans of Earth in terms of the stability of the environment.

Okay.

Well, that’s a good reason.

Yeah.

That’s my main answer to that point that Chris makes.

But there’s other objections like all that acid, you know, could life really thrive in sulfuric acid?

All that acid.

That could ruin your day.

Yeah.

No, I don’t mean that kind of acid, Chuck.

The kind that makes you hear voices.

No, I mean all that sulfuric acid.

But, you know, the more we’d study life on Earth, the more we find that life thrives in these extreme environments we didn’t anticipate.

And people have been sort of playing around with that alternative chemistries of life that could possibly survive.

So I think, you know, it’s just an interesting unknown.

And there have been some observations.

Neil, you mentioned the phosphine.

That’s controversial.

Did we really see phosphine in the cause of Venus?

Which if we did, it’s hard to explain.

And who gives you phosphine?

What life form gives you phosphine?

So on Earth, it’s weird things like rotting fish, you know, and it’s like it smells terrible.

It’s just this sort of by-product of actually kind of decomposing life.

It’s, you know, it’s a hydrogen rich molecule.

So it’s what we call a reduced molecule, which is common in biological materials, but not common in an atmosphere like Venus, that’s full of more oxidized and acidic materials.

So it’s not something you’d expect on Venus.

You expect there to be phosphorus, but it to be bonded with oxygen or some other compounds.

If it’s bonded to hydrogen, there’s something weird going on.

That would be oxidized rather than reduced, is the pairing of those words.

So for me, what’s intriguing about Venus is you can pre-choose a pressure and a temperature that might be good for your life in a particular layer of that atmosphere.

And this is why the surface temperature is irrelevant.

If you can find a nice cozy place at a stable layer in the atmosphere and that you can call home, it makes sense.

Well, right.

And where that cloud deck happens to be, that stable thick cloud deck I was mentioning, is at a place where the temperatures are moderate and the pressure is moderate.

Moderate to humans, yes.

But you can legitimately call that surface pressure uninhabitable, even not just being sort of human-centric or earth-centric because almost no complex chemistry can survive there.

Like no organic molecules.

Nothing that is bonded to anything else basically can survive there.

It’s so hot, it just rips molecules apart.

So that seems, even if you’re not being sort of earth-centric, it seems like that kind of temperature would be very hard for anything to live in.

So what do you fear most going forward?

With the budget, with culture, politics?

Is there, in terms of the health of the search for life in the universe?

Oh man, what do I fear most?

Well, I’ll answer that in a roundabout way.

Here’s something that gives me hope, which is that last year we launched the Europa Clipper mission.

Love it.

Yeah, and if you think about the time scale, it’s going to get to the Jupiter system in the early 2030s.

It’s on its way there.

It’s been launched.

They can’t stop it.

Well, amusingly, it’s on its way back to Earth now for a flyby, but it’s going to Jupiter.

You mean a gravity assist.

Yes, exactly.

So I think about that, and I think, well, okay, by the early 2030s, we’ll have a different administration, presumably.

We’ll have different leadership, but there will be a NASA.

There will be a science team.

We’ll be operating that mission.

Somebody will be here.

And, you know, so there’s the time scale of these these projects that we do in our field gives one a certain perspective.

They outlast administrations and government figures.

Now, that’s also a reason to be scared because things can be canceled and so forth.

So the fear that’s the flip side of that is my worst case scenario is things go so wrong that by the time Clipper gets to the Jupiter system, there is nobody here operating it, you know?

And that’s a nightmare for me, but I don’t think that’s going to happen.

It’s more a source of hope because whatever happens, it’s not going to be so bad and we will have a mission and we’ll get through this and we’ll keep exploring.

Plus if I can add, NASA has ten centers that are, that reside in eight different states, and those states variously vote, four red, four blue, five red, three blue, five blue, three red.

So NASA is embedded in our political landscape as no other agency is.

And so…

Everybody loves it.

And everybody loves space.

Yeah, everyone is looking up.

All it means is if you love NASA or hate NASA, you cannot deduce what their political leaning is based on that alone.

Based on that alone.

Right, right.

And just to put nuance to what you said, Europa Clipper is not just going to Jupiter, it’s going to Europa.

Well, it’s going to make 50 close passes by Europa from its perch orbiting Jupiter.

Gotcha.

Yes, Europa is the place we’re going to be looking at.

That’s where the action is.

Yeah, yeah.

Hey, let me ask you, now I know you’re a planetary astrobiologist and this is not planetary because I want to talk about an asteroid.

But I just read about some of the findings from Bennu and one of it was, I think that they had, they found 14 amino acids and RNA and we know that those are the building block proteins of life.

So that we’re on the same page.

Yes.

Bennu is an asteroid that’s the size of the Empire State Building.

It is on a collision course.

Well, it has an orbit that crosses Earth orbit.

It’s next close approach will be in 2182.

We went there with the mission Osiris-Rex, which it had touch and go, grabbed some of the material and came back and deposited back here on Earth.

That’s badass.

And we analyzed it and leading to what you just described.

That is badass.

Now pick it up with.

So what I want to say to you as planetary astrobiologist is, what are these implications of finding these building block proteins of life?

Does it just mean that that stuff is in our solar system and no big deal or does it mean that the likelihood of life is more likely someplace else?

What does it mean?

It’s really profound.

They didn’t find proteins, they didn’t find RNA, but what they found was all of the stuff you need to make proteins and RNA, the amino acids that make proteins, the nucleotide bases that make RNA and DNA, and they found sugars now too.

That’s all the basic stuff you need for life.

What kind of sugar did they found?

Domino.

A couple of different sugars.

I’m not remembering which ones.

I think ribose was one of them.

It was, absolutely.

Yeah, it absolutely was.

And these are molecules that have built in them quite a bit of chemical energy where you can set stuff into motion if you wanted to have some serious chemical action.

Very nice.

So there’s a couple of really amazing implications.

One is, I mean, remember this asteroid Bennu was just kind of chosen because as Neil said, it’s coming close to Earth but was also convenient to get to.

So there’s nothing about it that’s different from like thousands of other carbonaceous primitive carbon-rich asteroids out there.

But it happens to be full of the stuff of life.

What this implies is that when the planets were young, they were all being sprinkled with the ingredients for life, not just Earth, but all of them were being plastered with this stuff that’s sort of like the kit, the recipe, just add water.

Got you.

It implies not just our own solar system, but probably elsewhere.

I mean, again, we have to extrapolate, but there’s nothing that we know about the chemistry of our asteroid belt that’s probably different from that around other stars.

And so it implies that the stuff of life is all over young planets in the universe when they’ve just formed.

But the other weird thing is you can ask, so why didn’t it progress to life in this asteroid?

Why don’t you have proteins and RNA?

You have the kit, but the kit has not been assembled there.

So it also tells you something about that the progress of those materials towards life is not inevitable in every environment, that you need the right environment, but the stuff is everywhere.

You have the kit, but not the caboodle.

Right, right.

You need the caboodle.

You need the kaboom.

Nice.

So David, let me ask you some just completely out of left field questions here.

Remind us, you play an instrument.

What instrument is that?

Mostly guitar.

And it’s jazz guitar?

Well, funk and reggae.

Oh, funky spoon.

Funky spoon, excuse me.

Funky spoon.

So if aliens visited us, would you play your guitar for them?

Would they be able to hear it?

And would they want to kill you or hold you?

How might they react to your music?

Yeah, boy, that’s a great question.

I would love to have the chance to try.

It could be a tough audience.

That’s a tough crowd, I don’t know.

Because in close encounters of the third kind, musical notes were a fundamental part of the communication.

No, I mean, it’s a really cool question because there’s a lot of dimensions to that question if you start to think about it, because what is music?

Why is it that every culture on Earth finds it important and valuable to put together sequences of frequencies and rhythms and do this thing that we call music?

And is it possible that that’s so built in to what it means to have consciousness and a brain and a culture that that would be something that would be shared by extraterrestrials?

I don’t think it’s impossible, but it gets to these deep questions.

First of all, what is music and why is it so universal?

And second of all, how does it relate to our experience as conscious beings and is that something that might truly be universal beyond just this planet?

But you didn’t mean why is music universal.

You meant why is music Earthwide?

Yes, yes, universal on Earth.

Could it be universal?

Could it be universal capital U?

Right, and that presumes that the aliens have a sense of hearing, for example.

Not necessarily.

Maybe they actually would experience the vibrations of the music with that.

I mean, that’s what our ears are doing.

We do sonifications of other kinds of data, right?

So could we take our music and convert those patterns into whatever they could?

If they sense the vibrations, you would call that hearing, I think.

Yeah, you would.

You would.

But what I’m saying…

What David’s saying is that we have sonified other forms of data.

Correct.

And in fact, we did a whole show on the sonification of images.

That’s right.

Right.

Yeah, from Chandra.

Yeah, from the X-ray telescope.

Right, yeah, we featured Kim Arkans work on that.

Absolutely.

On stage, actually.

Fascinating stuff.

Yeah, but like I’m saying, if they had like the receptors all over their body and they were, you know, receiving the vibrations that way, we just have it in one little portal called our ears.

I mean, presumably they have some kind of senses.

It’s hard to imagine some, you know, cognitive being.

And whatever senses they have, they can perceive patterns and rhythms and so forth.

And so there’s got to be some way to play our music for them, even if it’s not just like…

I’ll tell you this, Dr.

Funky Spoon, if you play for them and the response is, all right now, all right, oh yeah, yeah, that’s my jam.

And guess what?

You have done some great work for bringing us together.

I think it’s worth a try.

Yeah, yeah, he would be the ambassador to the thing.

But I actually, I think there’s probably more appropriate, like Sun Ra, you know, or George Clinton with his mothership, you know, there’s probably more appropriate news to come.

What do you call it, Afrofuturism?

Afrofuturism.

I got to tell you, I’ve never thought of that, but if aliens come, we should definitely introduce them to George Clinton and the mothership connection.

Yeah, you know, the ship, the mothership, it’s in the National Museum of African American Art here in Washington, DC.

They’ve actually got that as one of their artifacts, so we can just take them over there.

Wait, wait, does the museum still exist?

Um, not for long.

No, stop.

I don’t understand it.

As of today, I believe it does, but there’s no telling about next week.

Well, I gotta go check it out then.

Oh, that’s a fan.

So, David, I think we’ve run out of time here.

Wow.

But like I said, it’s always good to check in with you.

Dr.

Funkist Boone!

And where do you perform in Washington, DC?

You got a hovel there?

Oh, there’s a few different places.

One of our favorite places to play is a VFW post called Hell’s Bottom in Tacoma Park.

Just cause it’s like, it was rated one of the 10 best dive bars in Washington, DC by the Washington Post.

And it’s just like a really friendly neighborhood place.

And we play there basically the first Wednesday of every month with the Groovadelics.

The Groovadelics.

Right on.

That feels very 1960s.

I like it.

Yeah, yeah.

There’s a number of places around town.

If you’re in DC and you want to catch us, the best thing to do is go on Facebook to the Groovadelics web page and we post stuff on there.

Excellent.

And you’re on social media as Dr.

Funky Spoon.

That’s right.

Correct, DR Dr.

Funky Spoon.

DR, very nice.

You got it.

All right, dude.

We love you here, in a minute.

Always great to see you guys.

We love you here.

All right, Chuck.

Always a pleasure.

We gotta have him every week.

Yeah.

Dr.

Funky Spoon is always a good time, man.

He’s always a good time.

This has been Star Talk, our astrobiology Dr.

Funky Spoon edition, because that’s where we get a whole fresh look on astrobiology anytime we talk to this man.

That’s right.

Neil deGrasse Tyson here for Star Talk.

As always, keep looking up.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron