It has been said jokingly that the dinosaurs might still be around if they had a space program. Humanity has numerous space programs, from NASA to ESA to JAXA to ISRO and more, but are we doing enough to ensure that we would escape the fate of the dinosaurs if an asteroid the size of Apophis was heading straight for us? With limited detection efforts like the Sentinel Mission, would we even know it was coming? Find out when Neil deGrasse Tyson interviews Apollo 9 astronaut Rusty Schweickart, co-founder of the B612 foundation, devoted to protecting Earth from asteroids. Explore deflection strategies and why geopolitics may be a more critical factor in their deployment than physics. Find out which is worse: an impact in the ocean, on the land, or an airburst like Tunguska or Chelyabinsk. You’ll learn what an impact is projected to cost, and why an actual deflection mission is such a bargain. In studio, Neil and co-host Eugene Mirman break down risk in terms of asteroid size and makeup: rocky vs. metal vs. a loose collection of rubble. Discover the “Deflection Dilemma” and whether any nation could use an asteroid to attack an enemy. Finally, you’ll hear what astronaut Franklin Chang Díaz’ revolutionary VASAMIR engine, the Association of Space Explorers, and The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry have to do with the creation of the B612 Foundation in 2002 by Schweickart, astronaut Ed Lu and astrophysicist Piet Hut.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. This is StarTalk. I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal natural physicist. And I also serve as the director of New...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal natural physicist.

And I also serve as the director of New York City's Hayden Planetarium, right here in New York City at the American Museum of Natural History.

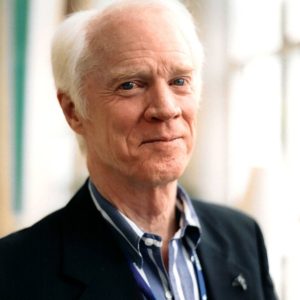

And we're featuring my interview this week with Rusty Schweickart.

He's an Apollo 9 astronaut, a genuine Apollo era astronaut.

And he's been hell bent on trying to prevent humans from going extinct.

Preventing Armageddon by trying to deflect asteroids.

And of course, I need some comedic help in this one.

So Eugene Mirman, welcome back onto StarTalk.

Eugene.

Eugene, thanks for having me.

So what you've been up to before we get cosmic, so you, I just read like in the news that you released like a nine album comedy track volume album.

That's also seven LPs and you can buy it in the format.

LP.

What year is this?

What are we talking about here?

2015.

The vinyl is getting more popular.

No, no.

So, okay.

So you have comedy for audio files.

Comedy for audio files.

Exactly.

And there's the volume of sound effects.

There's all sorts of stuff.

Okay.

I have to look for it.

I didn't believe it when I saw it.

Everything about it is true.

Everything that I read is true.

So, Rusty founded what's called the B612 Foundation, and it's private and not-for-profit, and all it's trying to do is protect Earth from killer asteroids.

That's all it's trying to do.

Are there, like, how many, how common is this?

There are squillions of them.

No, no, there's tons, but how many are killer?

We don't know.

We don't know.

We know the worst of them out there, we know where they are and how many there are, but that might not be the biggest problem, because for every one that would render us all extinct, there are ten others where they could just totally wreak havoc with civilization.

Okay.

Exactly.

Now, Rusty Schweickart, he was on Apollo 9, people that, it's a forgotten Apollo mission.

Apollo 8 were the first people to leave Earth and go to the moon.

They didn't land, but they went to them, took that famous photo of Earthrise over the moon.

They went near the moon.

And orbited the moon.

But Apollo 9 stayed in Earth orbit to test more apparatus before Apollo 10 actually went to the moon and also didn't land.

And then Apollo 11, they landed.

So what people forget is these weren't just single missions boldly going where no one has gone before from the beginning to the end of the trip.

Every piece of that was tested and verified so that we can protect human life and make it a fun discovery.

Glad they did.

Not the way I would have gone to the moon.

So he's now retired, of course, as an astronaut and he's a business executive.

And he's worked in satellites and telecommunications.

So he's sort of stayed and he's had a foot in the satellite world.

And he's also founder and past president of the Association of Space Explorers.

Do you know who that is?

That's an exclusive club.

It's only people who have explored space or people who want to?

Yeah, none who wants to.

So it's like less exclusive than presidents of the US but more exclusive.

Yes, because there are only how many?

Four.

Yeah, whatever the number is.

Right.

And this is in like 500 and something.

And it's international, of course.

Oh.

Yeah, of course.

Of course.

Great.

Cosmonauts too.

So he co-founded B612 Foundation back in 2002, along with a friend and colleague of mine, Pete Hutt, who is an astrophysicist.

And he's also brought on the US astronaut, Ed Lew, another friend and colleague.

These are all astrophysicists coming to bear on this.

Who have also been in space?

Ed Lew's been in space, but not Pete Hutt, not Pete Hutt.

And there's also another one of my colleagues, Clark Chapman, who's a planetary scientist.

So you have all the right people who know how to think about the solar system and protect us from it.

So let's go to the first clip of this interview that I held with Rusty Schweickart and just see where he's coming from and why.

B612 really came out of, actually out of an ASE meeting, an Association of Space Explorers meeting where Franklin Changdias, do you remember Franklin?

Mr.

Innovative Propulsion Guy.

Right, VASMER engine.

VASMER engine, plasma engine.

It's a plasma, magnetoplasma engine and at one meeting, Franklin gave us a lecture on the status of his VASMER engine development and at the end of his presentation, we're all saying, you know, what do you use it for, Franklin?

How do you see Envision using this incredible, unique breakthrough engine?

And among the things he threw out was pushing an asteroid and we kind of looked at each other and said that could be useful and we had a lunch.

After the lunch, all of us looked at each other and said, hey, if anybody picks this up and does anything with it, let's all call one another.

And so Ed Lew was giving a lecture at Princeton Institute for Advanced Studies in 2001 and got together with Pete Hutt, who was up there, astrophysicist.

I was there at that time.

You were there?

I attended his talk.

They got talking about it and they decided in the end to call a meeting at Johnson Space Center that Ed hosted in the fall of 2001 in October.

This was after 9-11.

The issue was we all knew the people who were there were very sensitive to and aware that we were finding more and more asteroids and yet nobody was doing anything about what do you do about it.

Sooner or later, we're going to find one where they're addressing it.

At some point, you're going to find it, but nobody's even thinking about that.

The two immediate questions were, number one, can anything be done about it?

We took about two days and it was clear that, yeah, if you knew about it early enough, yeah, you could do something about it.

Then the second question was, can we do anything to bring that something about?

That was, you got to form an organization.

You can't just do it by thinking.

That was the origin of B612 Foundation.

We named it B612 because in Ed Lew's kitchen afterward, he and Pete and I were sitting around drinking beer and we're saying, what the heck do we call this thing?

Pete said, I think that the little prince, number one, the little prince came from an asteroid, but I think it had a name.

And so we went on before Google, we went on the internet and Pete sure enough found that it was B612, was the little prince's asteroid.

And so we decided to name it cute.

B612, that's the cutest thing you ever heard.

So the author of The Little Prince is Antoine Saint-Exupéry, who's a highly literate poetic even aviator.

So he got to describe his experiences back in the day when very few people ever flew or saw what a cloud looks like from above.

And so he's written some of the most compelling statements about what it is to explore and to go where you haven't been.

And a little bit of that is in The Little Prince, because he hangs out on an asteroid.

So it's a little obscure and you got to be sort of child book literate.

It has been explained.

And so, yeah, have you ever worried about getting hit?

Yeah.

I mean, I kind of, I'm glad to know I figured someone like Rusty was out there figuring something out.

You hope that you expected that to be the case.

I was like, I'm a little worried, but some people who have a better sense of it are probably like, oh, I think I have a plan, though I didn't think the plan.

It sounds like their plan is to attach engines to asteroids and fly them away.

We don't have a plan yet.

That's an idea.

It's an idea.

Right.

We have, we have ideas for plans because if you blow it up, more little parts will come and destroy all of them.

So there are complications in almost all of these scenarios, but I don't know if, if, if viewers know the difference between a meteor, a meteorite and meteoroid.

You know the difference between all of this?

I think one is one that has already crashed and destroyed Russia and one that is on its way to destroy.

That's the difference.

I think one is one that's on earth and one is that's heading toward.

Yeah, so a meteorite, after you, after it hit and you pick it up, it's a meteorite, right?

And by the way, I think there are too many words for this stuff.

It's unnecessary, but we have it anyway, so here they are.

So if you pick it up and it fell from the sky, it's a meteorite.

While you observe it moving through the atmosphere, it's a meteor.

And usually, it's going so fast, it's rendered a glow as its kinetic energy converts to thermal energy.

A shooting star, but it isn't really a shooting star.

No, no, no.

It's not like a shooting star.

It is what a shooting star is describing.

Yes, and of course, it's not a falling star.

It's fun to watch when things get named because they're reminders of how little we knew about what the hell we were talking about.

Yes, it was named when people were just like, I wonder what that is.

I think we're being attacked by stars.

They're falling out of the sky.

There's also a part of the Bible in Revelations where it describes one of the signs of the end of times is the stars fall from the sky and land on earth.

Oh, and then the first time people noticed, I guess, meteors, they must have been like, oh, this is the end of times.

And they were like, wait a second.

No, it's not.

Somebody figured out it was not.

And one of the most famous ones of recent past, Russia has got both of them.

One happened in 2013 in, was it February, just earlier in the year.

It blew up in the sky or it hit?

Yeah, yeah, it was a sky blast.

And the shockwave shattered windows and people got lacerated from the...

Yeah, about 1,600 people.

I call it the Band-Aid because no one died.

But what an awesome shot across a bow that is, right?

That made people go like, Rusty, what's our plan?

What is the plan?

And so, that happened near the town of Chelyabinsk in the Urals of the western edge of Siberia.

And one back in 1908, Tunguska, that's a real famous one.

Another air blast, but it incinerated 10,000 square kilometers of forest.

The air blast and the energy from it did that.

Why aren't we weaponizing this?

And so, that area, that 10,000 square kilometers that got destroyed by the Tunguska blast, it's about the size of the San Francisco Bay area.

And so, that's bad.

If you can incinerate trees in Siberia, then we're all at risk.

Right, right.

Yes, then it would also probably hurt a city.

If those things had better aim, that's what would happen.

If there was an even more vengeful god.

And so, what do you do with these?

Do you blow them up?

Do you deflect them?

And the...

Do you reroute them?

Yeah, yeah.

Well, that's what deflecting would be, is a rerouting, essentially.

Well, I guess I think of deflecting as away from Earth and rerouting as like, I hate that guy.

Oh, okay.

Well, in space, it's tantamount to the same thing.

And so, one interesting question is, if you go to deflect it, suppose you fail, it's going to hit like the United States, let's say, and then we go to deflect it, and then it doesn't deflect completely.

Right.

And then it hits...

It goes to like Ottawa.

Let's not get crazy, but it's like Ottawa, and that's not good either.

So, let's find out what kind of thinking Rusty has already done on this subject.

Check it out.

In order to eliminate the risk to everyone, there are nations who will have to accept a temporary increase in their risk in order to enable that elimination of the risk for everyone.

You can't avoid that.

When you deflect an asteroid, you shift the risk profile from where it was going to impact across a bunch of countries on the way to getting that impact point entirely off the earth in either that direction or the opposite direction.

And therefore, you've got this geopolitical binary decision to make.

Do we make it pass in front of the earth or do we make it pass behind the earth?

If I have NASA and I'm the big man on campus because I got all the rocket engines and I'm going to push it so that it doesn't hit the United States, how are you going to tell me to not do that?

Well, by having this a collective decision of the international community and we don't know, again, we do not have the answers.

It's not as if the ASE in taking this to the United Nations had the answers.

We have the questions that they've got to face and we're rubbing it in their nose.

And they might not have thought about this because they don't know about orbit or anything.

They will not have thought about it and what we're doing is clarifying the nature of the decision that somebody is going to have to make and because it involves nations across the whole planet, it's got to be the collection, the international collection of nations.

Now how you do that, you've only hit one problem.

Who does it?

If one side of the line goes across Russia and the other end of the line goes across the United States, which way do you push it when you got the US and the Russia as the big dogs, right?

But it's got to be a collective decision and you base that, let's say, a possible criteria, which we've identified.

I can't even think of one other than that it's our rockets.

No, no, no, no, well, cost, it could be very cheap to move in one direction, very expensive to move it in the other.

It could be that it takes less time to move it across one way, the other way.

It could be that the other country is my enemy.

It could be that the pop, no, no, because we have to make this collectively.

So there aren't enemies.

We're all together in this thing.

How nice for you to think that.

We are.

We really are.

The other one is integrate the population on that red line one way and integrate the population on the red line the other way.

Integrate mathematically, not culturally.

Yeah, integrate mathematically, right.

You say integrate a population, normally that doesn't mean perform mathematics.

Count.

Add up.

Add up.

You say it after me.

Add up.

Sigma people, right?

Okay, that's a sensible, that's an interest, I wouldn't, that's so obvious and I'm embarrassed I didn't think of that.

Or maybe it's not that, maybe it's not the integrated number, maybe it's big city along this short leg and no cities along the long leg, even though the total number is greater.

So there are all different kinds of criteria.

This is what I refer to as the meat which has to be hung on the bones, the skeleton that we have created in the United Nations now.

That's a carnivore right there if he's talking about hanging meat.

So he wants to, so what he says integrate, he doesn't mean like the people from one city moved to the place of another.

And mate with other people.

No, no, that's not what he's talking about.

What does he mean exactly?

Well, in calculus, if you want to add up the behavior, if you want to add up the value of a curve line, of a function over some parameter, you integrate over that parameter.

And so he's being calculus fluent in a conversation that I was having with him.

Nice.

I'm glad that he knows calculus, which is one of the things that I'm glad about him.

So you know, the B612 now, that's not so much what they go under.

They go under the name the Sentinel mission.

And their priorities have changed over the years because, yeah, we want to deflect it, but that takes a lot of money right now.

Let's at least catalog everything that could do damage.

And we didn't have really good ways to do that.

So now they have a list of...

No, it's a list in progress.

Yeah, yeah.

No, not a fight.

I understand that it's not complete, but meaning they're collecting a list of potential dangers.

Yeah.

So they're trying to collect data on, discover and catalog at least 90% of the asteroids larger than about 140 meters.

And by the way, asteroids normally hang out between Mars and Jupiter, that's the asteroid belt.

But some of them are rogue and they cross Earth orbit.

So those are the near Earth objects.

And that's a separate subcategory of asteroids that this is designed to at least try to find.

Then when you have one headed our way directly, and you can confirm that, I think that'll motivate people.

Yes.

Well, I mean, the Russia one was...

That was pretty terrifying.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

And I saw the footage on that and it was great.

So, now you can ask, speaking of how terrifying it is, and how much power they...

Some of these have the collision energy of a thousand nuclear weapons, such as what was dropped on Hiroshima.

So you might ask, if you have the power to deflect it to save us, do you have the diabolical power to deflect it and destroy on purpose?

Yes.

Yeah, so that we...

We do?

Well, we have to ask Rusty.

Even though I'm going to say, yeah.

Check it out.

Let's see what he says.

If you build the power to deflect an asteroid out of harm's way, it's been argued that if you're diabolical, you can do the opposite.

Oh, yes.

Take a harmless asteroid and...

Call the deflection dilemma.

Deflection dilemma.

Right.

And it was written up by Steve Ostrow and Carl Sagan.

And it is for fairly technical reasons...

Are there evil people working in your organization?

It is, what do you call it, a chimera?

Yeah, chimera.

All right.

It's a chimera.

It sounds like it's right, but it's not right at all.

And here's the reason.

If you want to wipe out a city, you got to use a rock that's something like 30 to 40 meters in diameter.

How often does that happen?

That one comes close enough to the earth that you might be able to move it to hit the earth.

Once every 300 years?

That's not much of a weapon, right?

Yeah, in 300 years, we'll take you out, but let's have coffee for the...

If it doesn't happen to be in the right orbit where that red line happens to go over the enemy you have to make, then you've got to make new enemies so you can hit them with a rock, right?

So the rock lines up with the country you have to hit.

It's not real.

So you choose your foreign policy that way.

Yeah, that's right.

Build your foreign policy around the happenstance asteroid.

So the deflection dilemma is not a dilemma.

Right, it's much easier to use missiles.

Yeah, exactly.

We already can send a missile, an intercontinental ballistic missile, between any two points on earth within 45 minutes.

So to wait around for an asteroid, what are you doing?

Right, and no one will think it was an accident because they'll see you moving it.

You can't be like, oops, that engine.

And that paper that he was referring to that was co-authored by Carl Sagan came out in 1994.

And here I got the title here.

The deflection dilemma, use versus misuse of technologies for avoiding interplanetary collision hazards.

Why was it called I'm very paranoid?

Oh, that's the subtitle, I'm very paranoid and forget about regular missiles.

So of course, asteroids have plenty of other uses.

Imagine, you know, mining and things like that.

Right, because we can go and get all their gold.

Yeah, you get all the gold and no one's going to fight you for it, right.

Well, if you go that, that's true, if you go far enough.

Yeah, the asteroid-arians.

Yeah, and other stuff.

Can you mine and bring back to Earth or is there virtually nothing that's worth that?

Yeah, so that's a great question.

So to move things around in space is much cheaper than bringing it back down to Earth.

And so it might be that when you mine, you're doing it for other activities that you would be conducting in space.

Oh, right, right.

You wouldn't be getting all the platinum bring here, you'd be getting it to build a platinum bridge to the moon.

Somewhere, sorry.

Just as an example of a thing you might try to do.

What an interstate number that would be.

Well, when we come back, let's find out how much this kind of mission would actually cost, because that has to matter at some point on StarTalk.

Welcome back to StarTalk.

I'm with my co-host, Eugene Mirman.

Hello.

And we've been talking about protecting earth from asteroids.

By the way, asteroids took out the dinosaurs and allowed us to rise up and become something more ambitious.

Maybe there'd be some sort of human slash dinosaur that would rise once we were just like.

Well, that's what I'm saying.

So asteroids, they can be bad if you're alive at the time.

And good for you if you survive it and then you have more biologically ambitious species.

We could easily become winged.

So to get a handle on this, we're featuring my interview with NASA Apollo 9 astronaut, Rusty Schweickart.

And what I had to find out, I had some sense of it, but I needed to know what would a mission to deflect an asteroid actually cost.

And he, as founder of the B612 Foundation and the Sentinel mission.

Which originally we wanted to just put a little prince on an asteroid.

Yes, exactly, so let's see what he says about the cost.

An actual deflection mission, you're probably talking a billion dollars, okay, total.

Something that's 500 million to a billion dollars.

Well, that's well under our funding radar.

We could write a check tomorrow for that.

Well, an impact, even a relatively small one, would cost you probably a hundred billion dollars.

At least.

For example, Apophis, which is 280 meters, which is a medium size asteroid.

There was a cost model made for an impact, and that came out to be about 400 billion dollars.

Is this an ocean impact with tsunami taking out the West Coast?

That's right.

The big cities of the West Coast and the expensive homes.

How much is that, 400 billion?

400 billion dollars.

Total damage profile, and that's almost true whether it hits in the ocean or whether it hits on land.

It's not, it is sensitive, but not sure.

Ocean is also bad.

Yeah, they're both bad.

But that's the magnitude of letting something hit of that size compared with a billion dollars to prevent it from hitting.

So it's a no-brainer.

So it's a no-brainer.

Yeah, I mean a billion dollars, we piss that in Washington.

Yeah, though it's funny because as if there'd be like, well, it's gonna hit this town and it's like one billion to save the town, but.

Well, the problem is, yes, it's not just a thing that hits a thing.

It's a thing that hits a thing and creates havoc in a huge radius beyond the actual impact point.

But they almost all do, or there'd be, or no, they wouldn't.

I guess it could be like Russia.

So stopping the one that hit Russia wouldn't have been worth it.

Is that what he's saying?

No.

It kills like eight people.

Yeah, I'm just saying, if you hit a thing, you'll destroy the thing, but you'll also destroy huge areas surrounding it.

Right, right.

If it hits the ocean, it'll destroy.

And the land, I mean, it doesn't, it either.

It's gonna have devastating effects from far beyond the spot that gets to show that it has the crater.

Yes.

Yes.

And this is one of the great revelations of computer simulations of the consequences of impacts on global climate, on our transportation chains, our communication outlets.

So it'll basically completely disrupt civilization.

And he mentioned Asteroid Apophis.

Its official name is 99942 Apophis, named after the Egyptian god of death and darkness.

Seems fair, even though it's only medium sized.

Yeah, so it's about the size of a stadium.

Okay.

And a professional football stadium.

Yeah, or rock stadium.

I like that you've decided what happens at this stadium.

Okay, it was not built for rock concerts, so I think I'm legitimate in that claim.

All right.

But that one is, we have our eye on that one because that's gonna make a close approach on April 13th in the year 2029.

Oh wow, so we have like a thing that we might try to deflect.

Well, if you had any testing of your apparatus, that would be a way to do it because we know it's not gonna hit, so you can sort of poke it and see what happens.

We wouldn't accidentally turn it to hit us.

You would hope not.

But that April 13th, you know what day of the week that is?

I'm guessing it's a Friday.

You're a smart guy.

No, I'm one of the best guesstimators we have in America.

So that would be a valuable testing ground for any of ideas.

And give us enough time.

And I brought the right amount of time, so that's about 15 years away.

Yeah, even I could build it by that point.

And I don't know anything about engineering.

So let's find out, Rusty's thought about the difference between hitting the ocean and hitting land.

And out of the box, you might think hitting the ocean is worse, because it sends a shock wave throughout the ocean.

You have tsunami hitting every place that touches the ocean.

I'm gonna wait to hear what Rusty thinks before I decide which I think is worse.

Let's find out where he takes us.

What's worse, hitting the ocean or hitting land?

Depends on the size of the asteroid.

If it's a big asteroid, and I'm just gonna arbitrarily say, let's say over 250 meters in diameter, something like that, 200, 200 feet.

Apophis would count.

Yeah, apophis would count, right.

It's worse if it hits in the ocean, okay?

And the reason that's interesting, it's an interesting scientific reason, because if you think of something like an air burst, the energy with distance goes down as the inverse cube of the radius or the distance.

In water, which is two dimensional, it goes down with the inverse square.

So the energy that's deposited in the water ends up going much, much further before it dies out.

Okay, so the inverse cube is because an air burst, the energy is diluting into a spherical volume, whereas basically the ocean is flat and horizontal.

So it only goes into two dimensions.

And the energy transfer into the water is quite efficient.

So you got basically the same amount of energy to radiate, and water, you end up with over the horizon problems that people don't even know.

I didn't know that, interesting.

Yeah, I mean, this is way more complicated than you think.

Right, so if it's very big water is worse, if it's a little small air is worse?

Yeah, air is better.

I mean, we're talking about what?

Sorry, yeah, yeah.

I'm like, from the point of view of the asteroid, that's trying to really make things very bad for humanity.

Yes.

Yeah, yeah, so here's what's interesting to me.

Movies that do it right typically show asteroids hitting the ocean, because nearly three quarters of Earth's surface is ocean.

And so, the movie Deep Impact did just that, it hit the ocean.

They still wanted to destroy New York, but you get to do it with a tidal wave, with a tsunami wave.

And so, but movies like Armageddon, where the-

Well, they sent miners to drill, and then they played the Aerosmith song.

It's just different.

Did they play Aerosmith's song, I think?

Is that because his daughter is in the movie?

Well, I think their only number one hit is like a sort of ballad for that movie.

Really?

Now you know, listeners of StarTalk.

So, there's an interesting cross-pollination in the research that one would do with the consequences of an asteroid hit, depositing energy into the world, burning things, and climate change is a general exercise.

And if something happens in one place on Earth, what effect does it have elsewhere?

And so, it's a fascinating challenge.

And it has a lot of the same problems with making accurate predictions going forward.

What do your models tell you of the orbit?

You're gonna have to crash some asteroids into a few cities just to kind of get a really good idea.

Just to find out.

Of how to stop it better.

Is it so big that it would be better if it hit the land than if it hit the ocean?

So, all of these calculations.

Where do we deflect it to?

Can we deflect it away from Earth?

Or that might not be?

Ideally, but it might be too late that you can't.

And so, maybe you can push it to another spot on Earth.

So, I talked to Rusty about increasing the, this is sort of the accuracy of these predictions.

So, we can actually have an actionable statement on which to base our behavior.

Let's check it out.

You may have to launch four or five deflection missions only to find when you get up there that it's not gonna hit anyway.

Okay, because when you get there, then you get a really accurate trajectory on that.

So, what we really need is some way to put LOJAC on each of these asteroids, so it can report back to us where exactly it is in space.

Yeah, but let me get into numbers here.

Now, you're talking a million asteroid put a LOJAC on.

Now, fly a million missions to these things just to put the thing, no, no, no, no.

You wait until the work from the ground indicates that it is a potential threat.

Then you send an observer mission to get the asteroid.

So, then, yeah, so it's a transponder, I guess is what you call them.

Yeah, yeah.

Yeah, and it broadcasts where it is, and then we can know with high accuracy, and then we don't have these uncertain paths where it might hit Earth, that shrinks down that Earth circle, right?

You get something on the order of 50 times better accuracy.

You reduce the uncertainty in your knowledge that you get from ground-based telescopes by about a factor of 50.

Well, that's important.

It is, because it makes a difference between is it going to hit or not.

It may still be several hundred or even a thousand kilometers uncertainty on the Earth.

If you're evacuating towns and townships, that helps.

Oh, yeah.

Knowing nowadays you see hurricane maps where they show the possible paths.

Hurricane maps are great, because they show-

Because we're learning how to read those now.

People understand there's a probability it may go this way, it may go that way.

Right, and they change the color as you come off the center line.

And from day to day, there's more data and they change a little bit.

So people are gradually, with the national weather system, getting to understand that we don't know these things and can't know these things for sure.

And in fact, we're much better in space, because you're dealing basically with gravity.

Pure gravity, yeah, it's not the chaos of the atmosphere and the ocean.

Yeah, so these are complex issues that, like, we're glad people in charge have confidence.

Of their own organization.

Glad a bunch of astronauts were like, wait a second, this might be bad.

And we should also be glad he knows calculus.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, exactly.

Just to get back to that point on it.

And now just to quantify some of this, the explosion over Chelyabinsk, that was an asteroid about 17 meters across.

It was stony, made of stone.

There are several kinds of asteroids.

What are some of the different?

Others are really metallic.

So you get asteroids typically from a planet that never fully formed.

And then it goes, ah!

And so, and then there's such activity out there, it ends up getting shattered.

But while the planet is trying to form, it's in a kind of a liquid state, or a fluid state.

And when you're in that state, the heavy things fall to the middle and the light things float to the top.

So then when it begins to harden, you have a center with a ready filtered supply of heavy elements, like platinum and iridium and gold and iron.

Are metallic asteroids particularly more dangerous?

Yeah, well, because they will completely come through the atmosphere.

It's hard to bust them apart just colliding with us.

So different kinds of asteroids are out there and it makes for fascinating different uncertainties.

So what kind of damage it would make.

Right, so the scariest form of asteroid would be the core of an unformed planet.

Yes, that one is just get the hell out of the way.

So we would try to then move earth.

Superman would have to push earth out of the way.

So something Batman could not conceive of doing.

No.

So Superman or Archimedes.

Yes, whichever one we have access to.

Archimedes, you know, my favorite quote of his, what does he say?

You can't push the earth out of the way of a moving asteroid.

No, he would have said differently.

He would have said, well, I'll quote him directly, give me a place to stand and I can move the world.

You want people like that around in situations such as this.

So Archimedes was badass, just so you know, in case you didn't.

I did not think he wasn't.

He was the Batman of the old days.

Exactly.

And so in that meteor that fell over at Chelyabinsk, they calculated how much energy that was, and it was about 20 times the energy of the bomb over Hiroshima.

So here's the difference, of course.

That bomb over Hiroshima killed 50,000 people, 20,000 people.

And later from radiation sickness.

And so how come nobody died in Chelyabinsk?

You might ask.

I'm also curious.

I am asking, officially.

The one in Chelyabinsk exploded 20 miles above Earth's surface.

When you're going 40,000 miles an hour, however thin Earth's atmosphere is at that altitude, it's as though it's hitting a brick wall.

So the explosion is the abrupt encounter with Earth's atmosphere, causing an air blast.

So now all that energy dilutes into a 20-mile radius sphere before it hits the ground.

And so the shock wave was still significant, but it wasn't so bad that everyone died.

And it was, wait, how many miles again?

20?

20 miles up.

Okay.

And Hiroshima, how far was that?

Half a mile up.

Oh, yeah.

We were also trying to hurt them.

Well, that's how it was calculated.

It wasn't accidentally detonated that high up.

It's the kind of calculation you do in warfare.

You know why?

They didn't want to drop it too low, explode it too low, because then half the energy would just go and make a crater.

Yeah.

And too high, it would become to dilute.

So, there's the optimum, again, it's a military calculation done with the cold, dispassionate way that they do these things.

The way war is.

War with industrialized nations.

And so, you calculate that, and you figure the maximum damage to people and things would happen in about a half a mile up.

And so, that's what they did.

So, my point is.

I hope asteroids don't find that out.

And so, the metallic asteroids would get deeper in the atmosphere and possibly even collide.

Right.

So, it's, we wanna know.

Would colliding be worse than exploding a half mile up?

Yes.

It would.

Yes.

Yeah, but the metal holds itself together so well that it generally will survive.

So, the biggest surviving meteors on Earth are metal.

And we've got two of them in, you know.

You have two of them.

You have two of them.

Do you ever, like, secretly trip a little away and bring it home?

Like, I have one of the two, a little of the two meteors, or meteorites.

So, Eugene, we gotta wrap up this segment, but when we come back, more of my interview with Rusty Schweickart, and we're gonna find out, do we treat asteroid impacts like any other large natural disaster?

What's the thinking on that?

Because clearly, we have thought about other natural disasters.

How different would asteroid strikes be from that?

This is StarTalk, welcome back.

I'm here with my co-host, Eugene Mirman, and we've been featuring my interview with former NASA astronaut, Apollo astronaut, that is Rusty Schweickart, and co-founder of the B612 Foundation, and what they now call themselves the Sentinel Mission, and it's very Google-able, by the way, if you want to go in.

Sounds like something you can totally look up and verify.

So, the asteroid, I don't think enough people are thinking about asteroids.

Well, how close are some of the near misses?

Like, how close are some of the ones that have almost hit?

Well, let's just put some numbers on this.

We've got our crack team of researchers got this.

So, consider that less than 1% of the million asteroids larger than 40 meters have been identified.

Now, you might say, well, 40 meters, that's nothing, except that's not what matters.

The size is not so much what matters.

It's how much energy does it carry, because that energy, kinetic energy, the energy of motion, once the asteroid hits and is no longer moving, where does the energy go?

It goes, it explodes.

It explodes, it goes in, destabilizes the object, it explodes, it burns forests, it makes a crater, it kills people, knocks over buildings.

So, all of this is going on in an asteroid.

And so, the smaller you get, the smaller is your threshold of wanting to track, the lower percentage of the total we've actually recovered that's out there.

And so, another problem is, you can find an asteroid when it gets close and just misses us, but then, if you want to keep tracking it, it goes farther away from us, and then it's so dim you can't track it.

And you have to hope you find it on its next time around.

Is it orbiting our asteroids?

Everybody's orbiting the sun.

Everybody's orbiting the sun.

Even an asteroid that might hit us?

Even an asteroid that crosses Earth's orbit is orbiting the sun.

That's right.

And of course, most of them cross our orbit when we're not there.

Right, when we're not looking.

When we're not.

When we're sleeping.

When the Earth is asleep, asteroids.

But when you cross the street, trucks have been on that street, but they're not hitting you, because you're crossing them at a different time, even though you're in the same place.

You've really planned your street crossing quite well.

And asteroids don't have that level of planning.

Exactly.

And so you can end up just getting hosed by them.

And so just something to keep in mind.

And so the near ones, so we have a list of the ones that come nearby.

By the way, there's upwards of a half a dozen asteroids that we're tracking that come within a few Earth-Moon distances.

Oh, but meaning, so how far is the moon?

And we call those close approaches.

How far is the moon?

It's a quarter million miles away.

Oh, okay.

But that's not how you should think about it.

Think about it as, remember the schoolroom globe?

Yes.

I mean, it's maybe a foot across.

I do.

So ask yourself, if that is the actual Earth in your hands and the moon is actually your fist, which is about the right size ratio, where would you have to put the moon to be the right distance from Earth?

Seven miles away, I don't know.

I'm making up a number.

About 30 feet away.

Oh, I was really making it up.

Not right next to it as school books typically show because they would have to fit it on a page.

About 30 feet away.

So if an asteroid comes and it's twice the moon distance or four times, I don't, you know.

60 feet, 80 feet, 100.

Yeah, to me those are not buzz cuts.

If you come within our, what's called, cislunar space, that's the official name of it.

That's what the military calls the new high ground, basically.

Then, yeah, that's when I'm starting.

How often does that happen?

That sounds much scarier.

You get that maybe a few times a year.

Oh really?

Yeah, yeah, and I don't know the latest numbers, but last I checked it was a few times a year.

And Apophis on Friday the 13th in the year 2029 will come so close that it will dip below our communication satellites.

Here's a question.

Didn't Rusty say we're 50 times off our measurements potentially, or if we went into space we'd be 50 times, and put a, you know, tagged it, we would be 50 times more accurate.

Oh, easily.

So aren't we potentially super inaccurate about where this asteroid coming for us will be?

Yes, but the good thing about it is that we can quantify that ignorance.

How does that work?

That's something we need to find out.

So what you do is you just have a wider uncertainty path that you must confront.

You just go, so it's like a hurricane where you go like, it'll be in this range, but you know it's not actually gonna go to France.

And it's data, exactly.

It's not gonna make a bank a turn and go to the Bahamas if it's landfell.

So this is how you would do that.

And so Apophis is gonna come within our communication satellites.

Those are 23,000 miles up.

So to me, that's fighting.

Will it disrupt our texting and our swiping right and left?

I don't remember if it's metallic or not, but not likely.

It would make everyone swipe right.

We should find out if it's metallic.

Those sound a lot worse.

That would be funny if it made everyone swipe right.

Exactly, by accident it created hundreds of marriages.

The asteroid marriage, that's cute.

So we have had to deal with natural disasters in the history of the world.

And I wondered how different would this be from those.

And I checked with Rusty to see what he says.

So a question for you.

This asteroid that struck over Russia, a thousand people needed band-aids.

Yeah, 1500.

Yeah, the glass broke in their face.

Why is that any different from a hurricane or a volcano?

People get injured.

We don't go back crazy over it.

I mean, we do, but not in some kind of so organized a way as you are suggesting to deflect asteroids in the future.

Why not view the occasional asteroid strike as another natural disaster and we pull ourselves up by the bootstraps and get over it?

Well, the reality is we are going to do that for the ones that are too small for us really to detect ahead of time.

And Chelyabinsk objects.

Was just such an object.

Yeah, it was just such an object.

We're never really going to be, we will find some of them.

Make no mistake, we'll find, but we're never gonna get anywhere near the total population of objects that size.

So we're 99% of the time that we get hit by something that's, let's say, 30 meters or smaller, we're not gonna know about it ahead of time.

But above that, where you can do serious damage, like wipe out a city, we can know about those ahead of time, we can predict an impact coming, and we can deflect it if we know about it early enough.

So in this enterprise, they're the ones you know we can deflect, the ones that are too small you can't see, those come under the category of all the other natural disasters.

You just have to, you need disaster recovery.

And the lower part, the lower region of the ones that you can find, but are going to cost too much to deflect, you're going to use-

Because there's so many of them, they're so small.

Yes, because they're so small, it is cheaper to evacuate the impact zone than it is to try and deflect them.

It's probably not purely economic.

You're going to have real geopolitical components to that decision, but in the work we've done with the UN, we have identified that this threshold or this break, this line, has to be defined by the nations of the world.

It's gotta be defined geopolitically.

It's not a technical decision.

Yeah, I mean, the more he talked, the more I thought we were just screwed, because there's too much, there's too much, too many factors.

It's not just bat the thing out of the sky.

But basically, the little ones are just like regular natural disasters, but the big ones could destroy mankind.

Yes, yes, and so.

So those we should really stop.

So the one over Cheyabinsk, I said it was about 17 meters across, that one, by the time you know that in our atmosphere, it's too late.

And there's nothing, is there anything you can fly into it or anything?

That low?

Yeah, no, because it's traveling it.

So it's not only the speed is, if you break a thing into two pieces, now you have to evacuate two locations instead of one, if they're split and they keep separating.

And you haven't reduced its energy, it's all about the energy.

Right, the energy is still there.

The energy is still there.

Even if you break it into a million pieces, the energy is still there.

They might explode at higher up and be a little less damaging, but nonetheless, the energy gets.

And there's no option where you slow it down or catch it with some sort of gigantic mint.

Lasso it?

Yeah, lasso it.

Well, something has to be holding the net.

See?

Oh, or, uh.

Yeah, what are you gonna attach the net to?

Rockets that are leaving Earth.

Okay, so.

Maybe a giant sheet with rockets on every corner, an opposite parachute.

So, yeah, so these are, for me, fascinating frontier challenges on this.

So does he have an actual plan of how it would be stopped, or he's gonna go, UN, we're in serious danger?

No, see, he's hosted conferences where they invited engineers to come up with solutions.

And some people who are the kind, look, we got the nukes in the silo, let's blow the sucker out of the sky.

You know, you got some of those people.

That's a bad idea, right?

Well, it's, you know, we're really good at blowing stuff up here in the United States, but less good at knowing where the pieces fall after you've done so.

Whereas a deflection mission, you can judge how well you're doing while the mission is in progress.

Right, but we also, would it make sense to blow something up in space, or no?

If you can get it early enough and completely blow it to smithereens so that when it does hit Earth, they're just harmless meteors falling through the sky, it would be a hell of a meteor shower.

Yeah, yes.

So that might make sense, but once it gets to Earth.

If you knew you would accomplish that, if that's what you're betting on, I don't know that that's the right way to do it.

Right, right.

It's not a great plan.

Right.

I don't recommend it.

That isn't my recommendation after hearing all the evidence.

And you want to know who's really gonna lead this?

Is it Rusty?

Are there countries, you know, there's a whole other geopolitical layering on this.

Right.

Forgetting the science.

Just who's accountable for something that could hit one country versus another?

I ask that of Rusty, let's find out.

What's really left, frankly, is taking responsibility.

And the question is, with everything else going on, why should I, as a president or a congressman or whatever, why should I add this to the list?

88% of congress gets re-elected every two years.

But the fact of the matter is the public, as they come to understand this, with Chelly Abinsk and other, you know, the next ones that are gonna hit, they're gonna understand, at some point, they're gonna get that it's not expensive to do this.

Because the image in everybody's head is, this has got to be terribly expensive.

It's not.

It's less than one half of one percent of NASA's budget to do it up in gold.

So you're not talking displacing the whole National Space Program.

Why doesn't NASA have such a program?

Because NASA has no responsibility for public safety.

NASA is to do space science and exploration.

This is neither space science nor exploration.

It is public safety.

That's the naivete of the founding documents.

It is, and we have made recommendations to the Congress, changed NASA's Space Act to make them responsible for this one and only cosmic natural hazard.

And they have not done it, nor has any nation in the world yet assigned this kind of explicit responsibility.

And that's what's got to be done.

You know, the more I talk to him, the more you just want to kiss your ass goodbye.

So he wants NASA to have responsibility.

If not NASA, then who?

And if not now, then when?

Well, I don't know.

I guess it would be, MSNBC would be a bad choice.

They barely do any space exploration.

Hardly any.

Yeah, exactly.

And I can't think of a band that would be good.

U2 maybe.

They would probably.

And by the way, there's another layering of challenge here.

That some asteroids that have less density that we measure than what we know is the density of the rock that it contains.

And so that tells us maybe it's a pile of rocks.

And when we calculate the bulk density, we're adding in all the space between the rocks, having it come out less than what we think it should be.

If that's the case, how do you deflect a pile of rocks?

I don't know.

A rock-eating monster?

Well, that's what I'm saying.

If you attach a retro rocket to one of the bits of it, then it could just pull one of those rocks away and leave all the rest not all.

Would you maybe blow those up?

Well, that's what I'm saying.

So, these are the challenges that confront the deflection engineer, right?

And is the thing strong enough to move one piece of it and have all the rest of it fall?

That's really what it comes down to.

Gravitationally, you mean?

Well, so one of the great ones is gravitationally.

That way, you're not tugging on one piece versus another.

So, that is, Eugene, the frontier of our species, survival in this world.

And you're from Russia and all these like-hitting Siberia, so maybe-

Well, Russia's very, very big.

Is that why?

That's probably, I think, why they get hit a lot.

It's like they're the ocean of land.

That's a guy like that analogy.

So, Eugene, we gotta wrap it up.

Thanks for being on Star Talk.

Thank you for scaring me about asteroids.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

And as always, at the end of these programs, I bid you to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron