About This Episode

Is math discovered or invented? Neil deGrasse Tyson & Chuck Nice explore information theory, talking to aliens with prime numbers, Mandelbrot sets, and why math is often called the “language of the universe” with Grant Sanderson, the math educator behind YouTube channel 3Blue1Brown.

Chuck asks the big question: “What the hell is math?” Grant explains that math goes beyond numbers and symbols—it’s a universal system of truth rooted in axioms, like those laid out by Euclid in geometry. But is it a tool we invented, or a discovery we unearthed from the natural world? We explore both perspectives discussing how humans have shaped and been shaped by mathematical concepts over time.

Learn how math connects us to the universe—literally. Could aliens understand prime numbers? Could we communicate with aliens using math? We discuss practical applications and how we benefit from the mental rigor math provides. Should math be taught as an art form? Plus, learn about Mandelbrot sets and how simple math can yield complex structures.

We break down complex topics like information theory, and the central limit theorem, revealing how even the most abstract math finds its way into practical and scientific use. Learn how AI is entering the mathematical landscape, helping to solve problems that previously seemed out of reach. Tune in for a fascinating journey through the beauty, challenges, and infinite possibilities of math!

Thanks to our Patrons Dr. Satish, Susan Kleiner, Harrison Phillips, Mark A, Rebeca Fuchs, Aaron Ciarla, Joe Reyna, David Grech, Fida Vuori, Paul A Hansen, Imran Yusufzai, CharlieVictor, Bob Cowles, Ryan Lyum, MunMun, Samuel Barnett, John DesMarteau, and Mary Anne Sanford for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTChuck, we finally got a math person as a guest on StarTalk.

And one that I actually like.

You know, sometimes it’s very difficult to like math people, because, you know, they know math.

Coming up on StarTalk, we have an authentic math educator who’s going to tell us what we’re not thinking and we should be thinking anytime we think about math on StarTalk.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk.

Neil deGrasse Tyson, you’re a personal astrophysicist.

Chuck Nice with me.

Chuck, how you doing, man?

Oh, man, I’m feeling great, Neil.

Professional comedian and my co-host.

That’s correct.

In that order.

Sometimes, sometimes in that order.

So Chuck, I think this, we’re going to, parts of this is going to be a Cosmic Queries.

Yes.

But we have a lot to cover.

So it’s not going to be a full up Cosmic Query.

It’s going to be, let’s slip in what we can because the subject is math.

What?

The language of the universe?

Learn math, kid.

It’s the language of the universe.

You want to talk to the universe?

You learn math.

Learn math.

There’s one of the funnest experts out there on this very subject.

His name is Grant Sanderson.

Grant, welcome to StarTalk.

Lovely to be here.

Thanks for having me.

Yeah.

You studied math in college and you came out and you worked for the Khan Academy.

Oh, my gosh.

If you’ve never seen-

Oh, the Khan Academy.

I know.

If you’ve never logged in to Khan Academy, you go there and you can learn everything about everything, and they care about how you learn.

They don’t just slap you with a textbook, and it’s a completely different experience.

I would call it even joyous, learning about practically every subject there is to learn.

And if you fail to learn, you can look over your head while clenching your fist and going, Con!

It’s a real opportunity.

A Star Trek reference there for those who are not geek enough to catch it.

So, Grant, you have multiple math platforms.

You have a podcast, a blog, YouTube.

You have brilliant postings with millions of views.

And this is not trivial math that you’re doing.

It’s like real.

When I say real, I mean, it’s the kind of math that most people would walk by and say, I don’t need to know that.

I don’t want to know it.

It’s got nothing to do with me.

Yet you somehow turned the tables on that.

Now, before I ask you my first question, Chuck wants to ask you his first question.

Yeah.

And here’s my first question, Grant.

And it may sound a bit glib, but it’s not.

I’m very serious.

What the hell is math?

Okay.

What the hell is math?

What is math?

Because you know.

What the hell is math?

What the hell is math?

Okay.

Here’s why I ask just so that you get a bit more context.

Okay.

One, we started off by saying, hey, it’s the language of the universe.

You hear that all the time.

But when I think of it, I’m like, all right.

So we have these symbols and we’ve attached values to these symbols.

And then these values have concepts that are surrounding the values and the symbols.

If I came from another galaxy, I wouldn’t know your freaking math.

So how is it the universe, the universal language?

Well, okay.

So it reminds me a little.

This question came to me in another form.

I was at this wedding recently and a person I was just meeting there, who knew I did online math stuff, said very sincerely, like, why is geometry math?

Which is a different question from what you’re asking, but it sort of gets into this, like, what do we even mean by math?

And I initially answered, saying, it’s something that we can know very precisely.

So one of the oldest texts in math is Euclid’s Elements.

And one of the things he did there is he starts by laying out some axioms, saying, assume these things are true.

Assume that lines are a thing.

Assume that points are a thing.

Assume that if you have a point that’s not on the line, it’s possible to draw a line that’s parallel to it.

These sorts of things.

And with just five of these assumptions, then proves, rigorously proves things that have to be true beyond any doubt.

So in every other field, there’s a little bit of doubt.

In every other field, you’ve got this little thing in the back of your mind that asks about experimental error, asks you maybe I didn’t observe what there should be.

And the thing that really separates math out from the other things is that assuming you agree on the axioms, everything else, there is no more doubt.

It’s a truly rigorous proof.

So we can say that aliens might use different symbols, but ultimately, we’re thinking math is out there to be grabbed by whoever has the capacity for logical thought.

But it raises the question like, what are the axioms?

Like, where do you start?

I mean, you can have all sorts of different math.

Like, once you’re in an undergrad math major, you take all of these courses, like group theory or topology or what not, and they always start by saying, here’s some definitions.

I’m like, here’s the definition of a group and yada yada.

It’s a set with some added stuff.

It looks like gobbledygook.

And then you proceed forward and prove stuff.

But I think a very reasonable question that the students could always have is like, why is this the object we’re starting with?

We could construct all sorts of other objects and move forward.

And so there is this interplay with how it relates to the world and whether the math that you’re developing is useful or not.

Because I think if you take like a purely logical standpoint, you can develop a whole bunch of useless math.

And in fact, you could ask if some of the math being developed now, like maybe will never be useful.

But history has this strange trajectory of things that seem to be useless coming back and being useful.

But it’s a real deep question why.

There’s some mathematicians who do math only because they’re pretty sure it will never be useful.

Well, I mean, there was this rather famous mathematician, Hardy, who this was around the time of World War II.

He was writing this book called A Mathematician’s Lament, or just sorry, A Mathematician’s Apology.

Hardy was one of the teachers of Ramanujan, if I remember.

He was, yeah.

He was the one who, who answered Ramanujan’s letter and like brought him in.

Great mathematician, of course.

And he was played by, who’s the actor in the film?

Jeremy Irons, I think.

Jeremy Irons.

In fact, those who love our archives can dig up our Jeremy Irons interview, where we talk about that film where he played Hardy, the mathematician, and to get his reflections on, on what that whole story meant to him.

So I’m sorry.

I’m just plugging our archive.

One of my favorite actors combined with one of my favorite people in history.

So it’s like, it’s just such fate for me.

I can’t play if I haven’t listened to that.

But I mean, Hardy wrote some, he was sort of delighting in the fact that math will never be certain kinds of math.

And he was highlighting the theory of prime numbers and relativity will never be used as instruments of war, which is this irony looking back because prime numbers have a lot to do with cryptography.

Relativity has everything to do with GPS and everything with that.

That idiot.

But the fact that he delighted in it is a little strange, right?

And it’s something you would only expect from an academic maybe.

But it’s like even when they’re trying not to make it useful, right?

Even one of them is trying not to, it seems to kind of come back.

And so, to your question, Chuck, on what is math, if we just said it’s the things that we can know for sure, that doesn’t really feel satisfying because that somehow doesn’t tie into this bizarre fact where it also describes the world.

I would add that in the film Contact, not in the book, but in the film, the aliens first communicated with us using pulses that trace out prime numbers.

There are a lot of special sequences.

That’s probably the simplest of the special sequences.

So that was another use of prime numbers.

If we don’t know anything about prime numbers…

That’s what I’m going to say.

Let’s say, for instance, we call them prime numbers, but are those values universal?

So I think you meet an alien species.

They come to Earth.

You say, like, do you know about prime numbers?

They don’t know the language.

They’re like, what do you mean by this word prime?

You start tapping out like two taps, three taps, five taps.

You do that.

The alien species has done like any thinking at all.

They’ll be like, I gotcha, I gotcha, I gotcha.

It’s such a natural sequence.

It’s like, as soon as you have counting numbers and then you start to ask curious questions, any intelligent entity is going to stumble on like primes being a thing.

Just to be clear, all of this assumed that they count in base 10.

No, it doesn’t.

It doesn’t at all.

Yes, it does.

No, no, no, no.

If you just tap twice.

The number you assigned to, got it.

So how do you write down the number?

Yeah, that’s what you call it.

Write down the number.

You got it.

So we would write one, three.

Maybe they have a different base 10.

But if you just do 13 taps and then you do 17 taps, right?

And you keep doing all the prime.

Like any, you know, any AI, any alien, all of them are going to be in agreement that like this one’s important.

They’re tapping out the glypsorpion sequence.

Wow!

Exactly, exactly.

Yeah.

Chuck, know your prime number is just for this, just such an emergency.

Just in case I run into an alien.

Right.

So I hate to ask you this question only because I don’t like the question.

But why not ask you is, I’ll tell you why I don’t like it in a minute, but is math invented or discovered?

Well, it’s OK.

And forgive me for asking that question.

No, no, it’s a super common question.

Let’s do an example rather than like philosophizing.

OK, so one of the first substantive theorems that students learn in school is the Pythagorean Theorem.

Though at some point, whether or not we’ve forgotten since then, many of us will have come across that if you have a right triangle and you label the two shorter sides A and B and then the longer side C, no matter what right triangle you have, A squared plus B squared equals C squared squared.

It’s a cool fact.

It’s not obvious that it should be true.

It’s useful.

It lets you make all sorts of measurements.

It’s the first one you meet that doesn’t just fall out of definitions.

It’s interesting and it’s all that.

Now, if you ask, is that fact invented or discovered?

Initially, it feels like, well, it’s discovered for sure.

You go out in the world, you see right triangles, you can measure them.

It’s waiting there for you to see it and notice.

It’s waiting for you to see it.

But then you get a little further in math and then you start to ask questions like, what is space?

What is three-dimensional space, two-dimensional space and things like this?

And then one of the ways that mathematically you’re defining two-dimensional space is rather than saying, oh, it’s this pre-existing thing and we can put a coordinate system on it.

A lot of math will start from the coordinates themselves and saying it’s all pairs of real numbers.

So rather than saying like, oh, there’s this plane out in existence and then you put some like axes and you say this is your x-coordinate, this is your y-coordinate to get to a point on space.

You say rather than all the tricky philosophical questions about what is a plane and whatnot, we just say a plane is all pairs of real numbers.

That’s what it is and then you can do math forward, you can make proof and whatnot.

But then when you say what’s the distance between two points, and you have to assign them what they call a metric to the space, a way of telling distances, you make the Pythagorean theorem true by writ, you define a metric that makes it true, and there’s choices for other metrics that you could have put on it.

Then it starts to become sticky, like, wait a minute, is this, was this discovered anymore?

Or if this is how we’re doing all of our math where we say, you know, a plane is just pairs of numbers, and that’s mathematically what it is, then you don’t have that same, like, oh, it was waiting there to be discovered.

Wait, so, Grant, how different is what you described from knowing that there’s a variety of space where Pythagorean theorem applies as we learned it, but if you curve the space, then triangles are different, right?

A triangle, the angles sum to more than 180 degrees, where a traditional triangle, especially a right triangle, it all comes to exactly 180.

So this would be a different metric for the space.

Yeah.

I mean, so the idea that you can put different metrics on is sort of the superpower of being the mathematician, right?

You’re not constrained.

So, and non-Euclidean geometry was discovered before it was, well, I say before it was used in physics, but if you’re doing things on a sphere, that’s fine.

But before all of the relativity stuff, that really made it come to the fore.

Of course.

Right.

But this back and forth where you can have something that at one moment feels discovered and like this just kind of awe-inspiring truth, and at another moment feels like it was just baked into the definitions.

This is a very long-winded way of answering the simple question that you asked, is math invented or discovered, for like how I like to think about it.

It is both, but more specifically, I think you go out and you discover stuff based on your existing, either your world or your existing math.

You use those discoveries to inform the definitions of the next step.

And then you make more discoveries in that next step.

And then you use those discoveries to inform the definitions further on.

So basically what you’re saying is, math is discovered the way Columbus discovered America.

That’s basically it.

What if we define it as the West Indies?

By risk, we define it this way.

Grant, you have a perspective on education that I highly respect.

Even if I don’t agree with every bit of it, I deeply respect it.

And you part ways with many educators in that you don’t necessarily prioritize, I don’t want to put words in your mouth, so correct me if I misrepresent this.

You don’t put as a priority, you should learn math because it’s relevant to your life.

That’s a typical way a math teacher would approach it, worried that if they teach math and it’s not relevant to people’s life, they will just ignore it, get bored, go to sleep.

So I have two questions for you.

One, we probably agree that math more than any other subject is what people say is their hardest subject.

So how do you get around that if not by making it relevant to people’s lives?

So first of all, I think anytime there’s a discussion of education, we should tear out the idea that explanation is different from education.

The idea of making a YouTube video or making an explainer is a very different task from being an educator in a classroom, eliciting something from the student, and that you’re playing different games then, which is relevant to the answer here, I think.

Because if relevance is on the table, it’s within one hour from being able to explain why this piece of math actually touches someone else’s life.

Amazing.

Run with that.

That’s the most inspiring thing.

If someone can see how it’s useful for them.

I have all sorts of friends who hated math, but I lived in the Bay Area for a while, lots of programmers there, and they came to love math through programming.

Because they were into computer science, they saw that, hey, to do this graphics project, I guess I really need to understand matrices.

You also studied computer science as well.

I did, I did.

A lot of my social circles are in those spheres.

That’s a story I’ve seen many times, where here’s this bit where usefulness is what made someone finally like it.

That’s great.

But I think very often, utility is just not on the table for a given piece of math all that soon.

You want to teach some high schooler about the quadratic formula, and they say, when am I ever going to use it?

The honest answer for that student is, nine times out of ten.

Never, never.

No, no, not just never, never ever.

Okay, well, I made a mistake once.

I was giving a talk to Pixar, and I used this as an example, the quadratic formula, you’ll never use it, so we have to motivate in these other ways.

Then afterwards, all these graphics programmers come up, they’re like, we use it every day.

They’re like, it was used approximately a trillion times to produce the movie Coco.

I’m like, okay, okay, fine.

Yes, it can come up.

To be careful what you say to Pixar people, there’s some mathematically and scientifically literate folks working for Pixar.

But yeah, so for most people, never.

They’re never going to use it.

Then you say, why learn it?

You could say it’s simply not worth learning, spend your time learning other things.

But there’s something about the mental exercise of rigorous thinking that is so pure in a mathematical setting that it really flexes some muscles that are going to be useful elsewhere.

I’m a mathematician, go on.

Okay, no, it’s self-serving.

But I think the better analogy, if you want to tell a student why should they learn this, it’s like if you go to a football player and they’re in the gym and they’re doing some squats, and you say, you’re never going to be on the field with 400 pounds on your shoulders that you’re lifting in this particular way.

They’re like, no, no, no, it’s building muscles.

And so I think a lot of the math that we do in school, it’s the same motivation.

You’re saying, no, no, no, you’re not going to use this particular thing in the same way that out on the field, you’re not going to be doing like a literal squat.

But the muscles built doing it really do make you more powerful later.

That also, math can, and I think often should be taught as an art simply because it’s available.

And if you can get someone bought into the beauty of it, that is as inspiring, if not more so, than the utility.

And often done right, it’s more on the table than the utility is, given the constraint of, say, like a 20-minute online explainer or one or another.

Just to be clear, I’ve seen some ugly math in my day.

Put it out there.

I’ve seen some ugly paintings too, right?

But that doesn’t mean we can’t.

So tell me, would you count information theory as mathematics?

100 percent.

And what makes it so?

Well, part of it is what we’re saying.

It’s something we can describe very exactly.

Oh, that’s as we started this conversation.

The precision calculation is what you value here.

So you use information theory, I’ve been told, to help people in verbal.

How does that work?

Well, first of all, for those of you who don’t know, not saying that it’s me, but what is information theory?

For everyone else, Chuck.

For all the people out there that are listening right now, like, what do you mean, information theory?

So I will answer that question, Chuck, by way of talking about this project Neil referenced, where back in, I think it was 2022, whenever Wordle became incredibly viral on the English-speaking Internet, this is one time when I got sucked in just as a programming project to say, how would you write a bot that plays Wordle?

Because it’s so clearly something that a bot could play, but it’s just a fun programming exercise to do it.

As I was doing it, I thought it was actually a really nice motivating example to explain information theory to the general public.

Because here you’ve got this game that a lot of people like.

The first thought that I had for how to go about it involved these ideas from information theory.

I said, oh, this can help motivate.

To answer your question, Chuck, often if you have a situation where you’re playing Wordle, and let’s say you want to know, is it better to play as a first word?

The nature of this game, you guess some letters.

If those letters are part of the true word, that you’re like the secret word you’re trying to get, they’ll show up yellow if they’re there, but in the wrong spot, they show up green if they’re there, but in the right spot.

So it’s this game of using your previous guesses to get more information about what the true word might be, and there’s that word information.

And so the worst starting example that you could use is the word kayak, K-A-Y-A-K.

In some very exact sense, this is the worst starting guess.

Yeah, I’m already seeing it right now.

That’s a suck-ass word for what you just described.

Those rules you just described, that is like the worst word.

Because it’s like, what are the odds there’s a Y in the word?

It’s like not very likely.

What are the odds that a K is in the word?

Not very likely.

Right, you’re not hitting that many vowels.

So you have this sense that you’re not learning that much about the word.

By the way, the valuation of Scrabble letters tracks this very much.

Yeah.

Because the rarer letters have higher value.

Okay, go ahead.

I think we use this word information in a very heuristic sense, where it’s the idea like I learn a lot from doing something versus I don’t learn a lot.

But who made it actually rigorous was a very clever guy named Claude Shannon, who was working at Bell Labs and this is around 1930s, 1940s.

You’ve got all of these games to try to send information across a telephone line if you’re talking to someone.

But sometimes it’s noisy and so you might ask, oh, should we boost the signal?

Should we add more line?

How can you think more systematically about how well you can communicate?

And so he wrote this paper that’s like the seminal paper for what’s now known as information theory.

He was the first one to use the word bit in this paper.

So this was the first time that bits as a concept ever came up.

And the basic idea there was like, if you…

Let’s say there’s something where there’s two ways that it might go.

You flip a coin, it might be heads or it might be tails.

As soon as you see the results, you’ve learned something about which path the universe took.

And if there was only two possibilities, he said the unit of information here is one bit.

But let’s say there was like a hundred possibilities and you learn a specific one of those.

Somehow it feels like you’ve gained more information and he came up with a formula for quantifying this and then he used that formula and relatives of it to try to describe how much signal you can send across something that has a certain amount of noise.

And it made it such that there was a theoretical limit where you could say this is how much information we could try to get across.

And then clever and clever coding schemes could try to reach that limit.

Now, in the context of Wordle, this means that you can put a number to basically how good a starting guess is based on the Shannon entropy is like a fancy word for it.

But basically, on average, how much information do you expect to get from it?

Kayak has a terrible Shannon entropy in this context.

A word like slate is actually very good.

It’s got that E, it’s got that A, L and T are very common letters, S.

Even if it’s not going to show up at the end, it’s still a very common letter.

I basically made this video that was giving a walkthrough of using information theory type concepts and trying to motivate what those concepts were as a way of pursuing this little hobbyist game of writing a bot to play wordle.

Here’s one that you don’t really hear much, but it’s so important and that would be the Central Limit Theorem.

So the Central Limit Theorem is actually as important for why it’s like overused and like perceived to be more useful than it is for its utility.

But there’s a lot of things in the world that seem to be distributed according to a certain normal curve.

And here’s what I mean by that.

They don’t seem to be.

They are.

What do you mean seem to be?

Well, actually, no, this is a good fodder for discussion.

Let’s take heights, human heights, because I think this is a little bit in dispute.

So if you go and measure a whole bunch of people’s heights, you measure my height, your height, thousand other people, million other people, and you create a plot where you bucket it maybe by the inch or something.

So everyone who’s between 5’9 and 5’10 falls in one bucket, everyone between 5’10, 5’11, another bucket.

You do this for people in the same demographic, let’s say.

So we’ll separate men and women, same country.

You notice that there’s this shape that bulges in the middle and it tapers out on either side.

You do this for all sorts of other statistics, and you see the same shape that seems to bulge in the middle and taper on either side.

It’s not just that there’s lots of shapes that could kind of bulge in the middle and taper on either sides, but there’s a very precise function that you can use that describes this really quite well, even in all these different situations.

Got this funny formula, it looks like e to the negative x squared with some constants thrown in.

But the idea is that by having a formula to it, then you can make exact predictions like saying, hey, how many people, what percentage of people do you think would be taller than 6’4, or what percentage of males would be shorter than 5’2, and all of these sorts of questions.

So the Central Limit Theorem explains why this curve, and not any other curve, like why this curve comes up.

And just as importantly, it explains when it’s actually going to come up, as opposed to maybe false cousins of it that seem to kind of look like it.

Because the way that it will happen is if you have a lot of different events that you’re kind of adding together in some way.

So the pristine platonic example for a normal distribution would be something like this.

Let’s say you and I stand outside and we’re going to play this game where you flip a coin and when it’s heads, you take a step forward.

When it’s tails, you take a step back.

So you flip a coin, maybe take a step forward, flip a coin, take another step.

And you play this game not just with yourself, but with 10,000 of your friends.

So you’re all flipping your own coins.

Each time, half of you take a step forward, half of you take a step back, roughly.

And you flip, I don’t know, 15 times.

So you’re all stepping, some of you got very, very lucky and took 15 steps forward.

A more typical person, you know, maybe they took like seven steps forward and eight steps back.

But then if you look at where everyone is, that will follow a normal distribution very, very perfectly, or really, really closely.

And it’s because you have this idea that you were, you took a certain kind of random event flipping the coin and you were adding the results many different times.

And critically, all of those events were independent.

Each coin flip didn’t influence the next one.

Whenever you have this, a bunch of independent things that you’re adding together, it’s not obvious at all that that will always tend towards the same universal shape.

And it didn’t have to be a coin flip.

It could have been any other random process with its own little internal distribution.

And you always get this idea that adding up a bunch of random things, which are all independent from each other, lands you on this universal shape.

Now, the reason I was saying like seems to and and and waffling a little bit there is I do think that there’s a lot of times in statistics when people will assume something’s normal, when it’s actually not, or it would normally distribute.

Yeah, yeah.

Like, because I assume Chuck is normal, but I bet you’re the only one.

That’s why you say assume something that it would follow in normal distribution.

Yeah.

Especially when it comes to long tail events.

Yeah.

I’ve got to ask you real quick before you go forward.

Because when I’m thinking of this and picturing it, it almost kind of makes sense the distribution, because you’re only talking about a coin flip.

But you said any random, so let’s take 10 white marbles and put them in a bag, and one black marble and put them in a bag, and these people play the exact same game with the same number of picks.

You’re telling me that that same distribution is going to be represented the same way?

I mean, if it’s not a 50-50, right?

So yeah, this is good to be more precise.

So let’s say you pick out, very often you’re picking the white marble.

One in 11 times you’re picking that black marble.

You play this game.

They make 20 picks.

They’re all independent from each other.

You will still see a normal distribution.

What will be different?

The mean will be different.

So everyone will have taken many more steps forward than back.

So they’re definitely going to be shifted up the road.

To be clear, everyone, he’s a mathematician.

He used the word mean.

He means average, okay?

The average position will be different.

We have a mathematician in ours.

The standard deviation.

It’s not the stern distribution.

Just like, get up, you take a step.

I’m the mean distribution.

Take a step, damn it.

You loser.

No, it’s actually, it’s a very insightful question.

It’s a very insightful question because it gets at a thing that I didn’t mention, which is how like, okay, it’s not literally the same distribution where they’re in the same point in space, but they’ll be shifted up the road.

They might be like spread out a little bit more.

However, the curvy shape that you draw on top of it that has a very specific function, that’s e to the negative x squared, that’s not an arbitrary function, that with a couple of parameters you tweak that just tells you like, where is it center?

How much is it spread out?

Just two different parameters, it will still match that.

That’s the real surprise of it.

It’s like of course some things are going to change, like where is the center?

Of course the spread is going to change.

But the surprise is like that’s the only thing.

Somehow everything else that’s interesting about the specific ball and bag example you did, that gets washed away.

By the way, the fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background in the early universe between hot and cold around the average is exactly this distribution, which gives us information of what happened way back earlier at the Big Bang.

The quantum fluctuations that would have led to it.

Very powerful means of analysis.

Average number of prime factors.

You take some giant number and you ask like how many prime factors does it have?

And you average that for a bunch of giant numbers normally distributed.

It’s just it shows up in all these different.

Spooky.

Spooky.

Yeah.

Yeah.

It’s spooky.

Yeah.

But also I think there’s the regression to the mean for things where you have two smart people and they’re smart because of some combination of whatever happened in their life and then they have babies.

It’s not likely that the smart, that their baby will be as smart as they are because there’ll be a regression back to the mean of everybody else where.

So it works its way in biology, is what I’m saying.

Are you trying to create a depiction where I’m the baby here?

What’s happening?

One more thing before we go to Q&A.

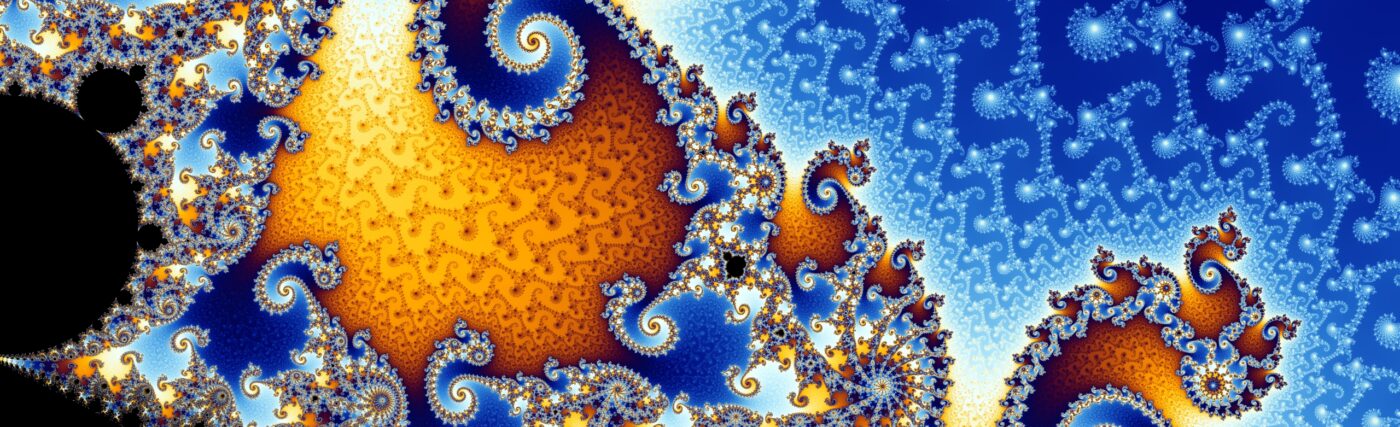

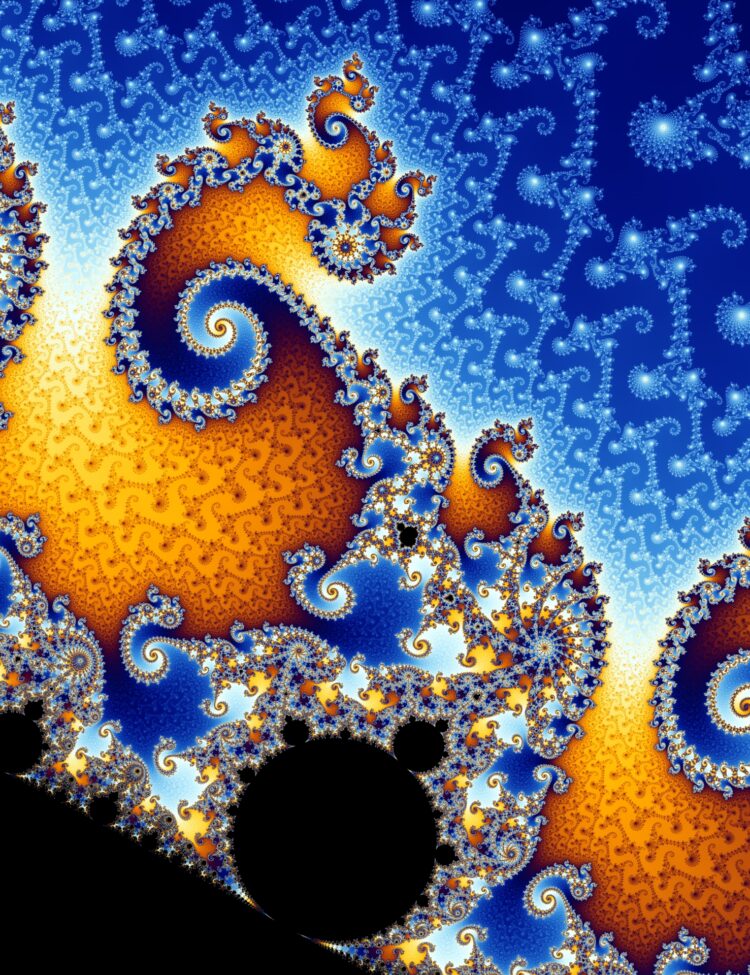

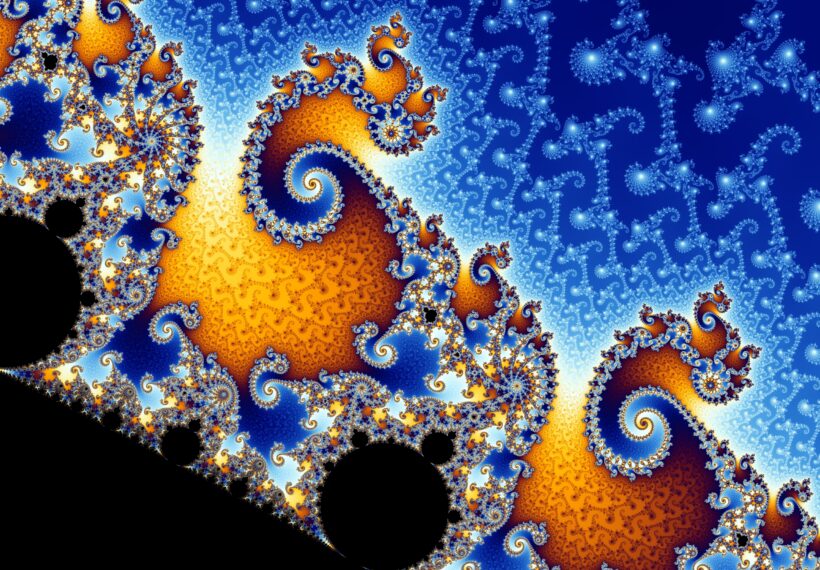

Let’s give a shout out to Fractals here.

Tell me about a Mandelbrot set.

Love me a good Mandelbrot set.

So this is one of those images that really captures the public.

Let me just say, in all my years of StarTalk, that was the geekiest thing ever said.

Love me a good Mandelbrot set.

Am I wrong?

No.

Oh man, it depends on how much detail you want here.

One version of this is to simply tell people, go to YouTube and search like Mandelbrot set deep zoom and then simply look and gawk at the shape.

And I think this is the way a lot of people engage with it.

It’s a really, really intricate shape that no matter how far you zoom in, there’s always more detail to be found.

And that’s cool in its own right.

What’s cool from the mathematician’s perspective is that it has a really, really simple rule that was used to describe it, even though it’s producing this mind-bogglingly complicated shape.

And that rule, stop me again if this is too boring or too much detail.

So, the heavy lift here is that you have to start by talking about complex numbers, which is one of those terms that like sounds more complicated than it is, because they literally use the word complex.

But in the same way that numbers we usually think of as being on a number line, there’s a really natural way of having numbers that live in two dimensions.

So you choose a point on two-dimensional space, and there’s a number associated with it.

And you can do things like multiply it by itself and add numbers to it.

Or do normal math operations.

Normal math, normal math.

And so you start at some point, and you basically say, all right, I’m going to call that point C as my constant C.

And then I’m going to play this game where I start at 0, and I’m always going to take the square of what I have and add C.

So for example, you start 0 squared is 0, and then you add C, and you get to C.

You’re like, great, I’m going to do that again.

I’m going to square the number, which is C squared.

So if C was 1, you would have 1 squared.

And then you add C to it, so you have like 2.

And you play this simple game where it’s almost like you’re at a calculator, and you’re just pressing the button Enter over and over and over, having done something like, what happens if I repeat this operation?

Sometimes the process blows up to infinity.

Sometimes it seems to stay bounded and bounce around.

If you color each point on the plane based on which of those two things happens, you color it black, if it doesn’t ever run to infinity, it just kind of bounces around a whole bunch, and you color it some other color if it goes off to infinity.

You maybe even give it a hue based on how quickly it runs to infinity.

That simple set of rules, which you can write with like three lines in any programming language, that very simple set of rules produces this mind-bogglingly intricate shape, and it shows how complexity doesn’t have to emerge from complex rules.

It’s possible for complex phenomena to emerge from very, very simple rules.

And I think that’s a powerful idea.

And by the way, Mandelbrot is a modern person, right?

When was he born and died?

Oh, when was he born?

I mean, 20th century.

In my mind, yeah, 20th century.

I think of Mandelbrot as like 70s is when I think of him.

Like he worked at IBM, I think.

I mean, his first name was Benoit.

Benoit.

Benoit Mandelbrot.

So I just found out when Mandelbrot lived, born 1924, died 2010.

Wow.

Yes.

A man of our times there.

Yes, indeed.

Very cool.

And so as you zoom in, you see new detail that is informed by the previous detail you just saw, but on a smaller and smaller, and it’s that all the way down.

Well, that’s the very classic famous depiction of a fractal.

Yes.

It’s the celebrity fractal.

This is just the A-list actor fractal that everyone wants to call it if you’re thinking of a fractal.

But since it can be defined so simply, the complexity is only what it looks like.

But in terms of information theory, it has very little information associated with it.

Because I remember, because I was active in the space briefly, and people wondered, can we use fractals to represent trees in an image from space?

We’re going to model what we forest versus land, non-arable land.

And then some of that was abandoned, if not all of it, because nature actually has more detail than the fractal.

So the fractal is like the lazy way to make it look like it has detail.

People do this in computer graphics too.

They’ll use fractals and fractal ideas to make it look like nature without having to use a lot of computer.

To actually do it.

Okay.

Now you have to hear my Mandelbrot joke.

Okay.

Tell me your joke.

Okay.

You probably know it.

So just, hey, what is Benoit Mandelbrot’s middle name?

I have heard this one.

So.

All right.

Go ahead.

Benoit Mandelbrot.

Of course.

Okay.

I have not heard that.

Of course I have not heard that.

That is good.

That’s good.

Can I correct?

I am going to be that guy.

Oh, so be correct me.

Correct me.

Did I misremember it?

Go on.

Go on.

Well, that is avert.

The version that I know that I think holds a little better.

His middle initial is B.

So everyone refers to him as Benoit B.

Mandelbrot.

And then you are answering this like, hey, what does that B stand for?

Well, it stands for Benoit B.

Mandelbrot.

Oh, gotcha.

Okay.

So then you are constantly filling in the B.

Of course, in the net there.

Okay, you got it.

That’s the foot.

Thank you.

I shortened it because my memory didn’t hold this whole joke.

I’m just going to let you know, as the resident layperson here and a comedian, it’s not funny.

No, I’m joking.

By the way, you might be our very first mathematician guest.

I’m almost embarrassed to say that.

I feel a little bit of hesitation with the word mathematician, because I’m not a research mathematician.

I often hold that in a certain high esteem.

Okay, so I’ll reword it.

Out of respect for your concern to not oversell yourself, okay?

You might be the first person we’ve had that truly loves math.

Okay, yeah.

You know, Brian Greene is going to be very upset with you for that statement.

Oh, that’s true.

Okay.

Yeah, man.

Yeah, but no, I wouldn’t call him a physicist there.

Yeah, he is a physicist, so no matter what.

Okay.

Hello, Dr.

Tyson, Mr.

Sanderson, Lord Nice.

This is Hugo Dart from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

With my six-year-old daughter, Olivia, we are such huge fans of StarTalk.

Mr.

Sanderson, what new possibilities does the evolution of AI present to the visual representation of mathematical concepts?

Is there a revolution in the area taking place or about to take place?

What do you know?

Thank you.

So is AI touching math?

Is that basically that question?

Yeah, it is in some pretty interesting ways.

So a couple different avenues.

One of them is using AI to suss out conjectures, things that you look at a bunch of data about something mathematical.

And a lot of times when humans come up with conjectures, which are guesses about what might be true that they have yet to prove, they just use their instincts.

They say, it seems like this might be true, maybe I should try to prove it.

And so there was some work with DeepMind where they essentially had some computers try to generate what’s the interesting math.

DeepMind is Google, correct?

That’s Google, yeah.

Yes.

Yeah, and so that’s one avenue.

There’s this other avenue where math lends itself to exactness, like we’ve been describing, in a way that also lends itself to computers very well.

And so this phenomena emerging really in kind of the last decade is a notion of proof-checking software, where when you write a theorem, rather than writing it in English, you write it in an actual programming language.

They can check for sure if the thing is true.

And so, for example, I get a lot like both real mathematicians and me will get emails from people claiming to have proven some famous unsolved problem.

And the normal thing to do with the emails is just ignore them because this is not the normal way that a real proof would get surfaced.

But proof checking software would mean that you can basically say, hey, if this is an actual proof, write it up in the software.

We’ll just run the software.

If it checks out, then we know it’s worth looking into.

But this interfaces with AI in an interesting way, where if you want to teach an AI to do math, you can just generate a whole bunch of proofs automatically, whatever you write it in this special software and whenever it compiles, whenever the software checks out, you know it’s valid.

And then you have these AIs kind of reinforcement learn on the ones that are true, kind of like when they play chess against themselves or play a game against themselves to get better by doing it trillions and trillions of iterations.

You can do this with math in a way you can’t do with other fields.

And so there’s this thing called the International Math Olympiad, which is…

I went to it this year.

It’s great fun.

Every country sends six high school age students to basically…

But you went to it not as a contestant.

No, no, no.

It’s for high school students.

I was about to say, you were old for the Math Olympiad.

No.

I was giving some lectures to the students.

But this was one of the first years that some companies had bots try to answer the questions.

These are quite hard questions.

They’re written proofs.

They’re not just like enter a number kind of thing.

And the AI, again, DeepMind was doing it, that they developed, got a score that’s equivalent to getting a silver medal at this International Math Olympiad.

And people didn’t think this would be possible because it’s considered such a…

It requires creative thinking.

It’s not just rote mechanics.

And so seeing this level of creativity, the reason that was possible is because they could do this game of letting a computer play against itself, in a sense, using these sorts of proof checking softwares.

So short answer to our friend from Rio de Janeiro.

Yeah, there’s lots of interesting interface with AI and math.

Corey He who says, hello, Dr.

Tyson and Mr.

Sanderson.

Sorry, Chuck, I don’t like you, so I’m not mentioning you.

I put that in there because he didn’t mention me.

This is Corey He from San Bruno, California.

We use base 10 and it still leaves us with a lot of irrational numbers.

Is there a number system that would make irrational numbers such as pi rational?

First of all, I used to live in San Bruno.

Hello, Corey.

Oh, really?

Then one answer to this question is no, whether a number is rational or irrational has nothing to do with how you represent it.

This cuts to our alien discussion earlier.

No matter what language we’re using, what base system we’re using, the idea of what makes a number rational or irrational, it’s intrinsic to the number itself.

It’s a property not of the description, but of the number itself.

Wait, let’s put this in here just because you have to help me out.

Pi, which is irrational and transcendental, in base pi would be 10, 1, 0.

What’s irrational about 1, 0?

The word rational will mean you can represent as a fraction of whole numbers.

The counting numbers, 1, 2, 3, 4.

If you can represent something as a fraction of those.

In base pi, all of the counting numbers, which are pretty natural object, you’re just counting rocks out in the world, would have these wild descriptions that take a whole bunch of different, we wouldn’t call them digits.

It’ll force everything else into a weird state.

Also, it’s not clearly well-defined what it means to be base pi, because what are the symbols you use?

With base 10, you have 10 symbols that you’re using to represent.

With base four, you have four symbols that you’re using.

But base pi, it’s not entirely clear what a non-whole number is.

It’s one symbol, but it goes on forever.

Okay, so you’re right.

If you made pi a nice, even-looking number, everything else relative to it has to die.

Give of its smooth life for you to make pi look smooth.

You could make it, yeah.

The thing that’s irrational, you could say, is the relationship between pi and the number one.

So it’s like whichever one of those you make look as natural as you can.

You have to own up to the fact that the relationship between the two has this property of not being a rational number.

Okay.

So the answer is no.

No, the answer is no.

Basically, you’re not going to be able to make pi rational without making everything else some kind of weird representation like that.

Can I add on?

That was his rational.

But go ahead.

Yeah.

I have a tendency to blather.

So definitely stop me if I go too deep.

Now, aside from talking about bases, you can talk about how do you represent irrational numbers where what we’re used to do is writing them down with decimals like pi is 3.1415, which effectively you’re saying it’s three and it’s plus one tenth plus four one hundredth plus one one thousandth, you’re kind of adding all these like powers of 100.

But there’s other ways that you could try to use numbers to represent irrational, like use whole numbers, counting numbers to represent irrational values.

And when I just want to throw into the ether for like the curious listener to go off and like land on the Wikipedia page if they want, is the idea of a continued fraction where it’s another way that you can use like a sequence of numbers of counting numbers to describe these irrational things.

I’ve had nightmares about continued fractions just so you know.

What can maybe turn those nightmares into dreams is seeing how certain values like the golden ratio or E, when you look at their continued fraction, rather than just having a whole bunch of arbitrary seeming gobbledygook as the digits, you see these really, really natural sequences.

And so somehow if you want a different language with it to describe numbers, like continued fractions offers another language that exposes the regularity in certain irrational constants, even if the fact that they’re irrational is something you can’t escape.

See, now this kind of strikes me as what we talked about in the beginning of the conversation, as useless math.

So Chuck, can we use fraction?

You know what gave me nightmares is you write it but you can’t write the whole thing.

It’s this fraction that just spills off the page.

But the same is true of of decimal values.

I can’t write pi, 3.1415, still not pi, 3.14159.

So you’re saying if I’m okay with that, I should be okay with continued fractions.

I don’t know.

I mean, they’re awkward, like the layout, because you have to use vertical space to kind of like…

Right, right.

And it grows as you keep going.

So I think we need a representation of irrational numbers where the numbers don’t believe that the earth is round.

Okay, yes.

All right.

Time for a few more questions.

All right, here we go.

This is Alyssa Feldhaus from Rocket City, Huntsville.

And she says, is there black hole math that we may be missing to see what the end result is beyond the event horizon?

So I like that.

So let me flesh that out even some more.

The limits of our theories of the universe, so general relativity has limits that are known in advance.

It cannot describe the singularity of the black hole or the singularity of the big bang.

And these are gravitational singularities where it has been said, God divides by zero, which you’re not supposed to do.

So is, and then the strength theorists march to the rescue, except they haven’t rescued anything yet.

So at what point do we say, Grant, that we’re missing physics, new physics to help us?

And at what point might we say, come on guys, give us another branch of mathematics and that will save us from our ignorance?

Now, is that a fair retelling of this question?

I think it might be.

I like that retelling.

I’m going to throw out a flag that feels like this one’s a little above my pay grade in terms of, like, I know a lot of the specific insights around understanding what happens at the event horizon have been, you know, this has been one of the most fruitful areas for seeing relationships between quantum mechanics and general relativity.

And the specifics of that, I’m not going to pretend to have my mind fully wrapped around to say, like, here’s what the insight will be that gets us one step further.

But maybe, Neil, you can provide a little bit of intuition on this, where I think broadly, the idea of alternate mathematical tools to understand that specific part of the universe feels like a ripe area for where progress can happen, where a lot of new physics happens at the boundary of what we can observe and have observed, and singularities give something that’s quite literally at this boundary.

And so I think, in history, when you have had new types of math come in to describe new physics, or it can even be old math that’s describing new physics, right?

Like when quantum mechanics was founded and people started using a bunch of matrix algebra to do this, it’s not like matrices hadn’t existed.

It’s just there was a utility for them that hadn’t been known before.

Same deal with imaginary numbers in quantum mechanics.

They had existed, but there was a utility that was then found.

Similar things might happen for whatever further steps one wants to make here, where there might be some existing math out there that hasn’t yet found a utility, but you try to use it.

We’ll get back to work so you can help us out.

Yeah, yeah, exactly.

Chuck, got time for just one more question.

Just one more.

All right.

How about Frosty from Tennessee?

You don’t know how he speaks.

What’s that?

You don’t know if he’s got that accent.

No, I don’t.

But he does now.

I’m Frosty from Tennessee.

I guess with a name like Frosty, he’s got it coming.

Yeah, man.

Frosty is cool.

Never mind.

Anyway, he says, many mathematicians speak of the beauty in mathematics.

How would you explain this beauty to someone who might view math as purely functional or just plain difficult?

And I’d like to add to that, do you have any insights into why so many people find math to be difficult?

It’s almost like all of civilization, there are people who like math and that’s 1 percent of everybody.

And then the 99 percent of people who hate math, was they worth subject?

Were they never, they never did well in it?

And then it was never intuitive to them.

As an educator in that space, take it on.

I think a lot of what’s happening is that the things that we do in school are pretty distinct from what mathematicians find beautiful when they’re referencing that.

So it’s not that they’re both looking at the same thing and one type of person finds it beautiful and then 99 percent don’t.

We’re looking at different things because in school, often what you’re doing is implementing a procedure.

You learn the procedure for adding two-digit numbers when you’re in elementary school.

You learn the procedure for solving for x.

You learn the procedure for taking a derivative all of these times along.

The thing that people find beautiful, all these different levels, whether it’s at the elementary or usually calculus is like the highest one that a high school might teach, all of it, it’s still very procedural and there’s nothing wrong with that.

That’s a necessary part of doing that.

That’s where you’re doing your squats in the gym.

This is building some muscles.

But the thing that is beautiful will be unexpected connections.

So seeing like, hey, I saw this bit of math show up off in this corner, and that same bit of math showed up in this completely different spot.

I mean, Pi is a really good example here where Pi shows up in all sorts of places you wouldn’t expect it to.

So I can throw down one very quick example for something that maybe anyone can understand why it’s at least surprising, even if maybe you don’t see beauty in it right away.

If I take one minus a third, you end up somewhere on the number line, and if I add one fifth, you kind of go up a little bit.

And if I subtract one seventh, and then I add one ninth, and I subtract one eleventh, and I add one thirteenth, and I play this game of basically adding and subtracting in alternating fashion, all of these like one over some odd number.

Ever smaller and ever smaller.

Smaller.

It kind of bounces back and forth, and it’ll approach one particular point on the number line.

That point is exactly pi divided by four.

You look at that, like pi is about circles.

What, why on earth would pi have anything to do with this game that I’m playing?

It’s got no business showing up on your timeline.

It’s got no business.

On your number line.

There’s so many, the normal distribution we were talking about earlier that describes, you know, statistics all over.

It has a pi in it when you describe the distribution properly.

Why?

Where’s the circle?

What on earth is going on there?

So that side of it where there’s a mystery, there’s this, it’s the opening chapter of a mystery novel.

You see this thing, you want to know like who did it?

Like why did this happen?

And then the path to resolution.

But I think if anyone enjoys a Sherlock Holmes story, for example, the part of your brain that that’s tickling, where you have this mystery at the start, some path that feels like it could be discoverable, but takes a little bit of cleverness along the way.

And then it’s satisfying to see the knot tied at the end.

Like that is the feeling that people are describing when it’s the beauty of math, which is different from the thing happening in most classrooms, which is the procedural side and understanding how to go through motions, which are useful, right?

But it’s just a different category.

Grant, you’re giving us hope.

Because people do like connections.

I mean, there’s that whole TV series and book series.

Who’s the host of that?

The British guy.

Yeah, James Burke.

Right.

It was about connections.

And of course, there was the geopolitical, social, cultural connections.

But nonetheless, I think we always like knowing that this over here is the same as that over there.

And when you didn’t otherwise realize that.

But I think the intrigue that you’re speaking to is far more important from an educational standpoint.

Because the procedure is kind of the work, the nuts and bolts.

Whereas what you are speaking to is the wonder and the mystery.

And these are all concepts that show up in life throughout life.

And that always spark us to think and to ponder and to something bigger than ourselves.

And if people were able to bring that into the classroom, I think you would find a lot more children being excited about math.

Not all educators are made the same, Mr.

Proctor.

Absolutely.

Yeah, I mean, honestly, I’m always fascinated when I listen to anyone talk about math, from Neil to you, to you name it, to Brian Green, to, you know, Brian Cox, you know, when these, the way you talk about math makes it so much more interesting.

But when I was in school, I had several teachers, especially in calculus, where I would get the right answer, but I got it the wrong way.

And that was the end of it.

They were like, yeah, you’re wrong.

You can’t do it like that.

And I’m like, okay, well, instead of, hey, let’s go on this little journey to show you, you know, how you’re thinking about this.

I never got that.

It was like, no, you got the wrong answer.

And honestly, it only took a little, I was like, clearly I don’t think right.

That’s when I came away from calculus.

My calculus experience was, I do not think right.

And that was it.

It’s your problem.

It’s all you.

So Grant, thank you for being a guest on StarTalk.

And once again, we can find you on all platforms with 3Blue1Brown as the handle.

And I don’t think you had to compete with anyone to get that handle on all platforms as you have successfully managed.

And you have a podcast, YouTube channel, a blog.

You’re active on X and Instagram as well, correct?

Yeah, there’s some short videos up on there.

Your YouTube is chock full of all manner of videos, some short, some long, some courses you even give there.

And they’re so popular.

And it gives us hope that not everyone in the world thinks of math as the worst possible thing they could give their brain attention to.

And you are living evidence of this.

So, so, Grant, thanks for being on StarTalk.

Thanks for having me.

All right, Chuck, always good, man.

Find you, Chuck Nice Comic.

Chuck Nice Comic everywhere.

Thank you, Neil.

Everywhere.

You got Comic C-O-M-I-C.

This has been StarTalk, a hybridized cosmic queries all about math.

Neil deGrasse Tyson here.

As always, I bid you to keep looking up.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron