About This Episode

What would life be like for astronauts on Mars? Neil deGrasse Tyson and co-host Chuck Nice dive into the world of simulated Mars missions with Commander Kelly Haston, who recently completed a NASA analog mission in a simulated Mars habitat.

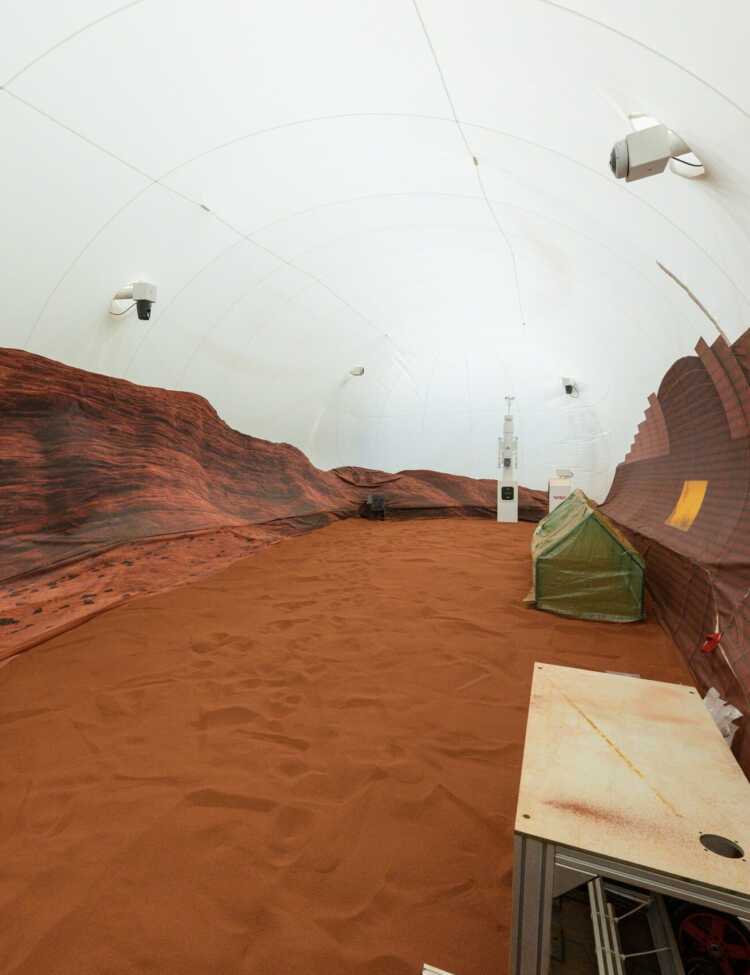

Learn about the CHAPEA mission designed to evaluate crew health and performance in isolation inside of a 3D-printed habitat at the Johnson Space Center, simulating the challenges of life on Mars. Kelly shares her experiences from spending 378 days in the habitat with her team, including a flight engineer, medical officer, and science officer. Discover how they navigated the psychological and physical demands of the mission, dealing with limited resources, and delayed communication with NASA and their families.

We explore the challenges of living in such a confined space, from growing food and maintaining a clean environment to the surprising dynamics of crew relationships under stress. They also touch on the importance of the simulated Mars environment, which included a VR setup for “Mars walks” and many troubleshooting tasks for the team.

We explore the tensions that arise when people are stuck together for so long, and what they get to bring with them to simulated Mars. What movies do Mars astronauts want to watch? Plus, do they keep staying on Earth time or switch to Martian time? And, learn about growing crops in the habitat and all the testing being done on the astronauts.

As they discuss the broader implications of such missions for future space exploration, Neil references sci-fi, including The Twilight Zone and The Martian, drawing parallels between the psychological toll of isolation in space and the themes explored in the show. The episode wraps up with a look ahead to future simulated missions and the ongoing research that will help humanity prepare for the real challenges of living on Mars.

Thanks to our Patrons Bob Zimmermann, Edward Bucktron, Intrepid Space Monkey, Cameron Ross, Mark Shashek, Lexi & Rick, Hidde Waagemans, Matthew Mickelson, Chris Vetter, John Haverlack, Brady Fiechter, and Adam Crowther for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTChuck, I love talking to folks with NASA.

Yeah, man.

Because NASA’s in our culture.

Yes.

And it’s not just a telescope showing a picture, they’re people.

I mean, there’s no wonder that they are the most popular branch of taxpayer-funded government activity.

And one of the most recognizable brands there ever was.

Absolutely.

Yeah, yeah.

And the fact is that we found out that you don’t have to go to Mars to go to Mars.

That’s what I like.

Coming up, life in a Mars habitat on StarTalk.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk.

Neil deGrasse Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist.

Of course, I’m here with Chuck Nice, Chuck Baby.

Hey, what’s happening, Neil?

All right, very nice, very good.

You’ve been doing all right?

You know, actually, I’ve been doing very well.

Yeah.

Okay.

This has been a great time.

The past few months have been.

Thank you for asking.

No, no, good.

I’m very happy right now.

We got to keep our comedians happy.

Well.

Because.

That’s an oxymoron right there.

Happy comedian.

That’s kind of the job of everybody.

We got to make sure you’re ready for the gigs.

Right.

So, you know what we’re going to talk about today?

What?

Simulating Mars.

Oh, my goodness.

I know.

Well, we’re supposedly get your eyes to Mars.

You know, we’re supposedly going there at some point, so we should simulate it.

So we figure out what we’re going to be in for.

Figure that out.

I have no expertise whatsoever in this.

OK.

So we found Commander Kelly Haston.

Kelly, welcome to StarTalk.

Hi.

It’s nice to be here.

Yeah.

So you’re you’re Commander of what?

So I was the commander of the first of three simulated Mars missions with NASA.

So even though you didn’t fly through the vacuum of space, they still got to call you Commander because the whole mission was simulated.

Yes.

Yes, I know.

How lucky is that?

I was going to say, does that make you a simulated commander?

Yes.

Yes, I’m I’m an analog commander.

Very nice.

You have a Ph.D.

in Biomedical Sciences.

That’s exactly the kind of, you know, that’s who you want.

That’s yeah, that’s in a Mars habitat.

That’s very Mark Watney of you.

But they didn’t leave her for dead on Mars.

And she’s still on Earth.

It’s a good simulation, too.

So we’re talking about NASA’s Chappiah mission.

Did I pronounce that correctly?

Yes, yes, Chappiah.

This reads like one of those tortured acronyms, but take me through it.

So Chappiah, and I will, it’s a crew, health, and it’s basically going to evaluate the health and performance of a crew in a one-year Mars mission.

So the idea behind it is to put people into a simulation where you can actually test how the isolation and resource restriction, including food, communication, water, all sorts of things that you, any kind of resource that you can imagine that you would need on a Mars mission, is actually in limited amounts.

And you have three, four people actually basically pretending to be on Mars and doing all the activities associated with keeping a habitat functioning and doing science while they are actually on a mission.

Now, you know, in other parts of the military, we call that enhanced interrogation.

No, no, you know what it is?

It’s a test to see if they’ll kill each other.

That’s all it is.

That’s a great reality show.

Yes.

That is a great reality show.

They have to leave their weapons outside.

I think maybe.

So, Chapia, I have here crew health and performance exploration analog.

Wow.

OK.

And it sounds like something you would put in yogurt.

Like, I’m so healthy.

I put so much Chapia in my yogurt.

So where did this take place?

It took place in a hangar on Johnson Space Center in a 3D printed habitat.

Wow.

So this is in Johnson Space Center in Houston.

In Houston, Texas, that’s right.

So it was 3D printed to simulate maybe what you would do on Mars.

You have to print up anything you need.

You can’t carry it there, right?

You can’t carry it, and you need to use the materials that are possibly present.

So obviously regolith, which is a soil that is going to be on the Martian surface, is a potential substrate that you could use to actually print something.

Other options, of course, are to be…

But just to be clear, regolith, when we think…

We loosely say Martian soils, but soil has a very strict meaning on Earth, which Mars does not have.

So what’s the difference between soil and regolith?

Well, there’s going to be mineral content differences.

So Mars is actually made up of the same minerals as the Earth, but it has different components, different proportions.

So you’re going to have different proportions of minerals present.

You’re also going to have a lack of moisture because Mars does have some water in the ice caps and potentially underground, which is pretty exciting.

But it does not actually have water content easily available on the surface the way our soil would have water content in it.

Therefore, it doesn’t support a biota in the soil itself.

Correct.

Okay.

So that’s why Mark Watney had to get, he made poop potatoes.

Right.

He couldn’t just grow it in the soil.

Isn’t a lot of the soil iron?

What do you do with that?

Well, you can’t do a lot with it other than actually build a habitat.

So you can actually potentially use it to create a habitat that might actually be both protective from environments and also potentially protective from radiation as well.

So that’s something that I think-

That’s great.

Yeah, exactly.

Yeah.

How long were you there?

We were there for 378 days.

Damn.

Oh, that is, that’s intense.

Whoa.

Yeah.

Now who do you hate most?

Let’s be honest.

Cause you know, it’s like day three, you’re just like, oh my God, this dude’s an egg hole.

So there’s four of you.

Who are the other three?

You can name them.

Yeah.

So we had flight engineer, Ross Brockwell, who is a structural engineer.

Neato.

Yeah.

And we had our medical officer, Nathan Jones, who is an ER doc.

So really versed in emergency medicine.

And then we had our science officer, Anca Solario, who is actually a microbiologist who works for the Navy right now.

So this is, and combined with your background, you guys can make anything happen.

Yeah.

Sounds like the nerdiest heist crew ever.

It’s like a heist movie with the nerdiest crew ever, which is awesome.

There was significant levels of nerd.

I can’t lie.

Yeah, no, that’s, and nerds know how to hang out.

We love that.

So before we get into some of the nitty gritty of this, I’m a big fan of the Twilight Zone series going back to the late 1950s, actually.

The original.

The original.

The original.

The original.

Not the Jordan Peele version.

Well, maybe I haven’t seen it yet.

I can’t comment.

Yeah, well, you don’t like it.

Okay.

Okay, right.

I’m sorry.

So that, if we remember, was the dawn of the space age.

Right.

And many of the episodes were made before anyone had been yet launched into space.

But we knew it was coming.

And there were multiple episodes of astronauts that are just alone in space.

And they’re exploring the psychological damage that can bring from being away from other humans.

Right.

And it wasn’t until I was older that I realized, you know, there’s long stretches of time I don’t want to be around anybody.

Oh, yes.

And I’m a sociable person.

So clearly, they’re like hermits out there where this would not be an issue at all.

Right.

Or fathers.

And NASA is always yapping at you anyway.

All right.

So this idea of isolation, is it as devastating as these psychological dramas would have us think?

You know, one of the questions that comes up is how isolating is it truly to be on a mission like this?

Or how isolating will it be?

That’s what it’s testing, right?

How are people going to handle this?

And I will say that it’s both incredibly isolating at times and also an opportunity to get closer to people.

And so amazingly, I feel like actually many of my relationships deepened during this period because there was less.

So first of all, NASA does speak to us all the time.

There was a significant delay.

Well, the good news is they could only type because there was a time delay of significant time delay across the mission based on how far Mars was from Earth during the whole mission up to 22 minutes one way.

So at the height of our time delay, it took 22 minutes for a message to get to us and 22 minutes for us to send an answer back or vice versa.

This is the time delay of radio waves moving through the vacuum of space.

Right.

So why would he repartee with NASA during this?

And why use, I’m asking you both, why use radio, why not use like some kind of laser communication?

All light.

It doesn’t make a difference.

All light has the same speed.

Same speed.

No matter what.

Same speed.

Right, right, right.

Okay.

So they built that in, even though you’re just sitting right there in Houston, they built in the time delay.

Absolutely.

And data size also comes into play there.

So it’s not just actually sending something, but how large you’re sending.

So the larger the item, so if you’re gonna send an audio file or a video file or even a picture, that’s going to take longer than just a typed message.

So you have all sorts of limitations there that you have to sort of take into account when you’re sending a message.

So we had communication with NASA, which was delayed for the same amount of time as our emails, but our emails would also take into account generally size.

So yes, we did actually have communication with NASA.

We had a schedule that NASA set up for us daily.

We followed that schedule similar to astronauts on the ISS.

We basically check marked our things off the same way they did.

We followed a red line of sort of timeline and had to do things in a timely fashion.

But we also would have to communicate back to them sometimes.

Or if we were troubleshooting, we’d have to ask them for help.

And then we’d have to wait for…

We’d either have to troubleshoot it ourselves or wait for that 22 minutes to hear back from them for what their answer was.

But that’s a great way to get yourself 22 minutes if you want.

They ask you a question and you just write back, please clarify and then go have some coffee.

Well, just a delay.

Yeah, exactly.

I don’t understand.

Please repeat.

I didn’t quite get that.

And then it’s like, all right, guys, now it’s time for some Maxwell House.

A badly behaved crew would potentially do that, but we would have never done anything like that.

Never.

To follow our own solution while waiting for NASA to let us know what to do.

But we did become quite autonomous in our responses.

And then in terms of communicating with your family as well, there was that delay.

And also things like video were very intensely data heavy, so hard to do for more than a minute or two.

You really relied on e-mails and audios.

But you did get to talk to people in that way, talk, I guess, in quotes.

And so, you spent more time than you normally did communicating with people, but you actually put a lot into it.

And my friends and family were amazing in that they gave me this richness of communication that I’ve referenced a few times where they really stepped up to a form that we don’t use anymore very often and communicated with me in this way and supported me through the mission.

And it was actually, I ended up learning things about people that I didn’t know yet.

So now, let me ask you this, and this may seem a bit juvenile, but I just gotta ask.

I’m not saying that it happened, I just wanna know what NASA’s policy is.

When it comes to a little romance happening between the crew members, are there any guidelines?

Like you find yourself having some warm feelings about somebody on the crew?

What happens in something?

Does you spend on a year with these people?

What happens in that case?

NASA probably didn’t, I can’t speak for NASA.

I can tell you that they did give us some information about that, and one thing, and I’m not sure if I’m supposed to say this, but I will say that pregnancy was an out.

Like you did not get pregnant on this.

You were not supposed to get pregnant on this mission.

And so I would imagine, given that it was Earth-based, if you did get pregnant, they would have removed you from the mission, potentially.

I’m hypothesizing on this based on information, maybe, that I was given.

We were also, the majority of us were partnered, so that would create some problems on Earth if you did get warm, fuzzy feelings about someone there.

So I think that, again, you’re in a professional setting, and humans are humans, and professional settings lead to relationships all the time.

So I’m sure that that could happen at some point, and we were lucky enough not to deal with anything like that.

However, I don’t know if, you know, once we’re in there, once you’re on an analog where you’re pretending to be on Mars, you’re on Mars.

And unless somebody gets hurt, they can’t really step in.

You know, they’re going to let the mission go unless certain things do happen that they’ve outlined ahead of time.

So I would say, luckily, we didn’t have those issues.

But it brings up something that I’m actually really interested in in future thoughts around analogs and also real missions, which is, is it better to send partners?

There’s a huge issue with sending partners in terms of crew dynamic.

But in terms of human happiness, there’s actually a reason to think about sending families or units of people, because if you’re going on a three year mission, a one year mission is actually relatively short.

Mars is going to be longer.

And so thinking about how we can send couples may actually be a viable way to keep people happier, although admittedly, that’s going to have to be a crew that comes together beforehand.

And there’s other inherent dangers in crew dynamic that could come up when you think about sending couples.

As part of the research.

You’re finding that out.

You’re finding that out.

Yeah, yeah.

However, I would love to see at least one experiment where that happens, where you have couples.

Because I just want to see that type back to mission control, which is, can we get a more comfortable couch sent up here?

Nine months typically is a journey to Mars.

You were not simulating the ride to Mars.

You were simulating your time on Mars.

But getting back to the pregnancy issue, there was a movie about this.

Really?

It was called, I think, The Space Between Us.

Okay.

Yeah, there was a woman who got pregnant the night before she flew to Mars.

Oh.

And then she delivers on arrival to Mars, because it’s a nine month mission.

Right.

And so, but NASA had to keep the whole thing.

So this was a child born and no one knew about the child.

And so the child grew up on Mars in 40% gravity.

And there was a whole story.

A secret Mars baby.

How much square footage did you guys occupy?

Ooh.

1,700 square feet.

No, no, no, no, what, what?

I’m done.

Sorry.

And you didn’t kill each other.

That was four people.

And you didn’t.

That was the habitat.

That was the habitat.

We did have outdoor area that we went out into when we mimicked Marswalks.

That was obviously in an outfit where we were mimicking a spacesuit.

So we did actually have a little, I call it going outside.

I loved going outside.

But our habitat, which we were in sometimes for weeks at a time, we didn’t go outside all the time.

So yes, 1700 square feet.

So when they go out, that’s when they sneak to McDonald’s.

She didn’t say where they went.

They’re just simulating, you’re in Houston, girl.

Guys, I’m going on another Marswalk.

How come you always come back from the Marswalk with ketchup on your suit?

What’s up?

So 1700 square feet, you could easily put four people in that living in a Manhattan apartment.

Yeah.

But you get to exit the apartment multiple times a day.

Which is why New York City streets are so crowded, because there’s a bunch of people living in these tiny little Mars bases.

It’s not an impossible area that I can imagine putting four people.

But when you have the urge to go on a Mars walk, where in Houston do you go?

Are you walking down like the street with a Mars?

Or do they have like a campus where this happens?

So within rate attached to our habitat, we actually had an area that was covered over and made to look like Mars.

So we actually exited the habitat, but stayed within a defined area.

And we used two different mechanisms.

We used virtual reality.

So we actually had goggles and a treadmill that we got on.

And we were able to go and do activities associated with scientific activities and also maintenance activities that you would expect to do.

So we actually went outside.

But you said goggles.

You mean VR goggles.

VR goggles.

Yeah, like a whole VR rig.

Like, you know, with the hand controllers.

Gotcha.

And the treadmill is to pretend like you were actually walking great distances.

So you can cover ground.

I mean, at this point, I’ve walked miles on Mars.

Yeah.

That’s super cool, actually.

But it does kind of feel like a little Truman Show-y.

It is, yeah.

Yeah.

What was your sky and your horizon?

So in VR, the realism was excellent.

Like it was the VR team was amazing and they put together a really beautiful package and set of activities for us that we got to do.

The non-VR was a little less realism because obviously you’re in a hangar in Houston that’s pretending to be part of Mars, you know, in a little area, but it actually wasn’t bad.

Like it was really the activities we were given, the builds that we were given, the different activities that we had to do outside, combined with the outfit that we wore did really sort of give you the sense again without the environmental issues of Mars.

So we were lacking that, but like, you know, so you can’t, you’re not going to mimic the difference in gravity or the difference in air.

You could, they could put a joist on all of you, right?

To make you just a little bit lighter.

Yeah, they could have done that.

You’re right.

And we did have aspects of like, I think again, what we, I always think about analogs is, what are they trying to ask?

Here, they were trying to mimic the workload that would stress us out or tire us out or be the thing that actually made you physically or mentally tired.

They were not actually, trying out equipment for an actual Mars mission.

So, we were addressing very specific things and that was not in the scope.

So, but that would be really, really cool.

You can imagine another such mission, an analog mission where it’s just for the gravity part.

Yeah.

And that would be amazing, right?

To really try that out and see how that would feel.

But you would have to rig both outside and inside.

It would be, resource-wise, it would be quite a heavy lift for no pun intended.

On Mars, it would be about 60 pounds, is that right?

Yeah, that sounds about right.

Yeah.

So you’d have a very different experience.

I’ve got to get to Mars as quickly as I can.

My goodness.

That’s not how it works, Chuck.

You don’t leave the fat behind.

What does Mars do for man boobs?

Because that’s where I’m really having the problem.

So of course, you’re in a hanger, so you never exit the hanger even when you go out on your walks.

Now I figured that out.

I mean, we didn’t see anyone, we didn’t hear the people outside of, even though, I mean, it’s the weirdest feeling.

You enter this habitat and you enter this space that you’re going to be living in for 378 days.

You know that mission control is in a wall, just a few doors down from you, and yet you don’t see them for a year.

You don’t speak to them directly for a year.

You don’t hear them because they’re being quiet.

What an incredible labor of love they did, which is they spent a year working in a place where they had to be bone quiet, just so quiet, so that they didn’t actually interfere with the mission at all.

So it’s a really strange, I mean, analogs are really funny that way because you have to buy into it on both sides.

The ground has to be the ground, the mission in space or on a planet has to be the mission.

So it’s a very real thing.

As a scientist, I can tell you that it’s a really interesting thing to see all of us drop into it and then experience it.

Everybody had different approaches and different ways to deal with it, but we all did do our best to do the mission as if it was real so that we were giving the best possible data to NASA because that’s the key, right?

Why else are you giving a year of your life up?

At any point psychologically, do you begin to believe the cosplay that you are involved in?

You’re actually on Mars and you don’t want to actually exit because that could mess up your brain.

Do you actually go Daniel Day-Lewis on us and just like, you know, I’m actually here, I’m doing this, you know, I am building a butch.

I can honestly say I did not.

I wish I could say I did.

I think it would have actually made it a really interesting experience as well, but I think you’re always, it’s almost impossible to turn your brain off and know that you’re not on Earth.

There’s just a number of differences, right?

Like that you’re not going to experience similar things.

So you are aware of it, but you’re so determined to do the mission in the way that it’s set up, that I think that you buy into the experience in a very deep way.

Like the fact that we were this unit, this team that was functioning together, and that we had to continue functioning together to do our work properly and so forth.

Even to think about the work, right?

Like doing science in this setting is not the way I do science normally, right?

I do science and I actually produce particular types of data.

Here we were doing making data for the sake of actually producing data personally.

So we were actually making science that, for want of a better word, didn’t matter.

It was creating data of a different sort.

And it was kind of a layer that I was…

You’re the data.

You are the data.

Yeah, but really, I am doing the science is actually the data.

Me doing the science is the data.

And then, you know, the capture is…

Yeah.

Yeah, and by the way, that was also a Twilight Zone episode where there is an actor on a set who had such a miserable home life, but his acting role, he had a joyous family and loving kids and everything.

And he just flipped one day and became the actor that he was acting.

You know, and they took down the walls of the things.

What are you doing?

That’s why…

No, it was, the Twilight Zone been up and down these streets multiple times.

A couple of other things, the, I seem to remember some studies where they put people in a room where they could live whatever bio rhythms was natural to them.

I don’t know if that’s the right term.

And when they did this, they found that 24 hours was not a natural unit of people’s, what do you call it?

A circadian rhythm.

That it was more like 25 and a half hours.

Oh really?

So when they would left to their own, their schedule shifted against, so it made you wonder is our life and our 24 hour clock forcing us away from what is natural.

So did you do Martian days or Earth days?

Ooh.

So Martian day is what?

Martian day is a little longer?

Yeah, the Martian day would be a little longer, so it would actually be perfect to that.

It would actually speak to that study.

We did not, and I can hypothesize a few reasons for that.

Number one, when we do activities on our schedule, right, some of them can be autonomous, like cleaning the hab or doing maintenance on the hab or whatever, or our personal time, obviously.

But there are other activities where we need an expert on the ground that’s actually monitoring us in case there’s troubleshooting to be had, right?

So our time, and similar to anyone that’s gonna go to space or do these trips, is also going to be dependent on the crew in Houston or whatever space station who’s actually monitoring them.

So we stayed to the Earth clock.

No, no, I’m not lying to that.

No, no, because when we sent actual missions to Mars, the folks at JPL have two clocks on their wrist.

They have Mars in time and Earth time.

Yeah, yeah, how many Sols are there?

That’s right.

Sol for suns, sundaes.

And so they’re forced to match the circadian rhythms of the rovers.

So make Houston go on your schedule.

Don’t, don’t.

Well, I would say from the experience that I think that, and this is just my experience, not NASA’s opinion of this, but I think having had this experience, that the crews that go to Mars are going to be far more autonomous than what NASA is used to.

Like the time delay means you can’t wait 45 minutes for an answer most of the time.

You have to go forward with your troubleshooting solution, unless it’s something that can be put off and changed to a later time in the day after you’ve heard from them.

So to be honest, I think that the, the environment and also the delay and the length of time that people are going to be there, I have a feeling it’s going to be a very different style mission, even than what we’re doing right now.

So even though I think that they’re, they’re getting close to trying to actually answer questions about safety and health with analogs like this.

By the time we go to Mars and actually have people living there, I think they’re going to have like ironed out some of these things.

And I have a feeling that people’s biology is going to actually, you know, adapt and reign supreme.

So in the end, I have a feeling that will probably be the case.

But for our analog, we did stick to Earth time.

And so, yes.

You’re going to put me away for a year?

You will follow my schedule.

Yeah, I am the one that’s up there.

I would get belligerent about it.

Exactly.

So let me ask you, when you said cleaning the hab, how do you guys divvy up those duties?

Is it a group thing where you all get together?

Okay, so.

And where do you put the dust that gets swept in the corner?

Right, yeah.

And what do you do if somebody’s kind of a slob, just like Jim, how many times are you gonna leave your space drawers in the middle of the dog on hab?

What’s up, man?

Seriously, where are the units here?

Space drawers.

Is that a different kind of drawer?

So you had to, you were self-sufficient, right?

So food, washing clothes.

Everything.

So we had everything.

So there was a presupply in certain locations, so we could get things delivered to us from those presupplied areas.

We had depots that were potentially, so there were times where we retrieved things from those resupply areas.

That’s a simulation of what a supply ship would deposit.

Exactly.

On a crewed supply ship in a drop.

Exactly.

Yes.

But there were instances, and there were things where we just had everything we were going to have in the Hab from the very start.

And so right from the get go, for cleaning supplies, we inventory them and we actually, we were tremendous, I will be braggy about that a little bit and say like, our crew had so much stuff left over because we really were like very resource.

We were like so tight on the resourcing that we actually had abundance at the end in some of our items because we just were really strict and we reused things like crazy.

We were like recyclers like you wouldn’t believe.

So that was kind of awesome.

But for the cleaning and all the different activities, some of them were assigned.

So sometimes we would go to our schedule and it’d be like, you know, Commander and FEN, the Flight Engineer are out today on EVA.

So those would be dictated by our schedule and by NASA.

But other things we would actually have.

NASA will never call that spacewalking.

They have to say extravehicular activity.

Uh-huh.

Okay.

You know, I feel like just slapping them.

What?

Okay.

Okay.

So your FEN is out on an EVA.

Go on.

Okay.

Yes.

But other activities like cleaning and so forth, we would come together as a crew at the beginning of the week and look at the activities that we sort of were either assigned for or thought needed to happen.

And then we would divvy them up.

And so we had a pretty fair system where we kind of kept track of who did what the last time and cycled it around so people didn’t get bored.

But also, luckily, I didn’t see anybody in their space scotchies.

So yay for me.

That was great.

That would have been not good.

And also-

Yeah, those are not normal men.

But we were really clean.

Men left to themselves.

They just, you know, drop their pants, walk around in underwear all day.

Listen, we will seek our lowest common denominator of existence.

That’s who we are.

It doesn’t make a difference.

You know, my mother said to me once, she came into my room, she was like, when are you going to clean this room?

And I went, why is the question?

You’re asking about time.

I’m talking about reason.

So we don’t see a reason.

All right, so we always hear about these tasks that everybody has to perform, particularly if you’re doing science experiments, it’s timed or it’s, all right.

What about movie night?

I mean, what do you do for entertainment?

Wow, yeah.

So the crew was, we had a little bit of preloading.

So A, we met each other during evaluation weeks when they were choosing the crew.

Preloading, that’s when you drink before you go out.

Oh, that’s pre-gaming.

Well, no alcohol, pre-gaming, yes.

No pre-gaming on this mission.

No alcohol on this mission.

However, pre-loading is probably a better term than pre-gaming.

Yeah, pre-loading.

Pre-loading.

Hey, man, I’m going to tell you, I’m pre-loading.

I’m ready to go.

We should start that right now.

Yeah, it should be.

We do pre-gaming.

Pre-loading.

Forget pre-gaming, we’re pre-loading.

Okay, so we interrupted, go on.

No, that’s okay.

So we were really collaborative at getting together before the mission.

We had a limited amount of data that we were each allowed to bring in and a limited amount of personal items.

So there was a weight limit to our personal items.

We actually made sure that there was very little redundancy in both the movies we brought in, the music we brought in, the books, et cetera, et cetera.

So we really did actually combine all of our resources, including like if you wanted to do a Christmas or a holiday celebration, one person brought in something that would be appropriate, but not all of us, right?

So we were really trying to like actually do that.

So we had a really big movie selection in our personal data and we watched, I don’t even know how many of them there were, but we watched like, it seemed like every Marvel movie.

We actually had a checklist that we went off.

So that was like for a period of time.

Did you watch the movie The Martian?

We did not watch The Martian, but I had read the book already and one person read the book while we were in.

Okay.

All right.

Just because I have to say this, Andy Weir is a friend of our show and we’ve had him as a guest.

Yes.

He handed me the highest compliment I ever received.

Which was?

Because he’s an engineer turned novelist.

He said, Neil, when I was writing The Martian, putting all the good science in it, he said, he imagined I was looking over his shoulder.

Right.

Yeah.

Well, because he knows that at some point, you would have been trash in the movie.

He didn’t want me tweeting about it.

That’s it.

At some point, you would have been like, clearly, this is not physically possible.

So they don’t let you watch the movie Titanic on Ocean Liners and you didn’t watch Martian on your Mars.

So when you say…

We did watch…

There’s a TV show about Mars that we did actually watch.

I’m blanking on the name right now.

But we did…

What is it called?

It’s like a NASA.

It’s like an alternate universe NASA TV show.

Oh, yeah.

That’s For All Mankind.

Yes.

For All Mankind, thank you.

And we did watch that.

That’s where the Russians got to the moon first.

And then, of course, we were behind on everything, including getting women into the space program, the whole deal.

It’s not a bad series, actually.

I mean, I think they bumped women and people of color up because of the Russians.

So it really actually did us some good, frankly.

Because women got to go to space way earlier in the alternate universe.

I have a solid state disk, and I have 300 movies on it.

What do you mean you’re limited in how many movies you can bring or how many books?

Why would there be any paper at all?

We live in the digital era.

Sorry, I was talking about e-books.

But we did have a data size limit.

There was a data size that they gave us, which was all we could bring personally.

I don’t have an answer for that.

I do.

Because they don’t want you spending all your time watching movies.

It’s real simple.

It’s the same reason you do it with your kids.

You limit the time that they’re able to be on their device.

I can imagine, though, that in any mission, the majority of data, you want to go to mission priority items.

The items that are going to support the mission’s objectives, the stuff for personal is limited in that it’s going to be, this is what you personally can bring.

In the same way that the limit of weight, so how many clothes you can bring, how many personal items you can bring.

Can you bring a guitar versus a keyboard, if you really love music versus, I actually needle pointed.

So I brought sewing items and needle pointed everything I could possibly think of to do with the mission, including the Chapilla logo, which is right behind me.

Yeah, a guitar you get to bring, but you can only play it in your room.

Stop.

Don’t subject the rest of us to your awful guitar playing.

Unless she’s good at it.

Unless you’re really good.

Yeah, I went to summer camp for two weeks and there was no television, no phone, no nothing allowed.

And one guy bought a guitar and I swear, I wanted to kill this dude after two weeks.

Cause every night it was him trying to very poorly figure out a rendition of whatever he was playing.

Oh, it was terrible.

Terrible.

Just cause you had a bad experience, doesn’t mean everybody else has got to follow that.

I’m just trying to protect you.

For me, just speaking as a scientist thinking about this mission, it’s especially interesting if something unforeseen happens.

Ooh, Martian bear.

What?

A Martian bear invades the compound.

Something unimagined, some new virus that only exists if four people are in the same airspace for a year.

Exactly.

You find an extra set of footprints leading around the back of a habitat.

What’s that?

Right.

Then it’s like, okay, we did this experiment to explore the limits of what we…

That’s any experiment taken to the limits is going to discover stuff.

Oh, that’s cool.

So that’s the whole point.

Yeah.

Okay.

Why did we build James Webb to go where we’ve never seen before?

And so you expect to discover stuff we’ve never seen.

What have you discovered, either anticipated or not?

Or did and did they throw you a curve?

Like, did they throw something in there to like, you know, kind of throw you guys off kilter?

Oh, that would have been good.

So I do want to point out that the experiment is not over.

There’s two more missions planned.

So for people.

So I’m a I’m a stem cell biologist.

I get to work with hundreds of millions of cells when I do my experiments.

Right.

I make I make different cell types and tissues out of human stem cells.

So I could make a heart cell or a set of heart cells that would communicate with each other.

I can interrogate.

You created yourself for this interview.

Exactly.

Right.

I could.

Well, there’s some issues with that.

You’re just a simulation of stem cells turned into the commander.

The Kelly clone.

That’s who we’re talking to right now.

Even though four people can create a ton of data over a year, it’s still only four people.

So the additional missions are going to add a lot of complexity to the data set, so it’s not complete yet.

I can’t really speak to exactly what we found out because it’s a very long-term experiment.

It makes me grateful that I’m a stem cell biologist because I get much more immediate answers than these people studying us do because they’re going to have to wait for years.

But I think that there were some really interesting findings about how we interacted.

I think that the crew and the team on the ground was really inspired by some of the solutions we came up with to some of the things that did happen to us.

I’m being a little bit vague because of the additional missions.

We can’t really actually, we don’t want to tweak them or give them too much insight into what’s going to happen so that they’re not actually, you know, so that they remain comparable to us, right?

You’re protecting the integrity of the setup.

Exactly.

But who analyzes the data that you produce about you doing this work?

Because it sounds to me like a lot of the information that you are gathering would be data to be analyzed by social scientists, psychologists, behavioral scientists.

Do they have those at NASA?

No, no, you publish it and then everybody sees it.

Oh, is that, so you just, oh, that’s cool.

But to answer your question, they do.

So they had a plethora of people at NASA working on this.

And a tremendous amount of groups came together to integrate the study and design it that way.

So we had people thinking about exercise.

We had people thinking about the team dynamics.

We had people thinking about the food that we were eating.

We had biological sampling throughout the mission.

So the data they collected was actually vast and across many different types of data.

And so each group came together and they will actually integrate that at the end when they, when they can analyze all of the people in the study.

She said biological sampling.

I think they’re just collecting her poop.

I’m afraid that’s true.

Okay.

Wow.

So let me ask you, before we…

I’m thrilled and I’ll just tell you guys cause you seem to like to talk about it.

I am thrilled to not be pooping into a container anymore.

Okay.

Okay.

I gotta tell you, I’m not.

I think I would rather enjoy the experience.

I’m just saying, I’ve never…

I ain’t going into space with you.

You know what?

The third mission still needs people.

I think the second mission might be closed, but you could be ready to apply for that third mission and be Mars analog astronaut just like me.

Now I have to put on my physicist hat and ask you, my last, I think we’ve run out of time here.

My physicist hat is over the 370 days, what was your energy source?

Because that would be responsible for imbuing the food with energy if you grew your own food.

So for your own nourishment, for your own warmth, for your own heating food, that energy has to come from somewhere.

Right.

And so did you have solar panels out front the way you might have on Mars?

And were they only operating 12 hours a day?

And at Mars, the sun is like half as intense or something.

It’s farther back.

So what was your energy budget?

Because the box stops at the energy.

I don’t know how much I can answer about that, but I can tell you that I did clean a lot of solar panels during maintenance.

So we definitely did have an aspect of that built into the activities we did.

Just to be clear, so on Mars, there’s a lot of dust storms.

So dust can just land on your solar panels.

And so you dust, it’s like the hump at the home plate.

You got to get out there and clean those panels.

So yeah, that’s a very natural thing you’d have to do on Mars.

Yeah, okay, go on.

Yes, and similarly in terms of resourcing and how that functioned, that was part of the experimental design.

And I don’t know if I can actually disclose it, but in each case, we were given limitations for certain things that the mission was interested in.

And so that was something that they measured throughout the mission.

And that will probably be some of the items that we actually are unblinded to when we actually see the final data set from all three missions.

So there is some element to that that is a little bit on the low down just so that we don’t actually disclose too much.

I think I just heard NASA has a secret energy source that the rest of us are not privy to.

Oh, who knew?

Look at that.

So all of us suckers are out here burning fossil fuels while NASA is luxuriating in their own special energy source.

So another thing, just to clarify, since this was not a mission to see if you could generate your own food, your module was preloaded with food, with a year’s worth of food.

So we had food basically that’s the same as what’s on the ISS.

We had dehydrated food and we had shelf stable food, but we did get to grow crops for certain parts of the mission.

Crops in 1700 square feet!

How could you use the word crops?

These are potted plants, right?

When you haven’t had fresh vegetables for six months, then it feels like a crop.

Because, man, you are happy to eat those.

So I would say, yes, we did have a very small scale grow area, and we were able to supplement with that.

But I think the idea being that, in any mission, you hope to always supplement for people with fresh vegetables and fruits and so forth because you would want that.

You could not have lived off of that.

No.

And if it failed for any reason, right?

If you ever had like a virus come through or a fungus or something like that come through, if anything, a bacteria, anything that took your plants down and you were relying on them, you would be hosed, right?

So any mission that goes to Mars or any place or the moon or wherever.

Interstellar.

Right.

A blight hits the crops.

Yeah.

So obviously, you’re always going to have to…

And NASA, that’s, I think, one of the reasons that NASA loves analogues is that you get ready for every eventual problem, right?

It lets you test out and practice in a safer space where you’re not going to hurt people.

What’s going to happen so that when they actually get there.

And I think that Chris Haffield has said this really nicely, that analogues just really make your muscle stronger in these areas.

And then you actually know what to do when you’re there, right?

And that’s not for the people that are pretending to be on Mars.

It’s for NASA, who’s actually preparing that way too.

So they’re getting all this data on how to keep us healthy.

But they’re also actually testing how to keep teams happy and how to grow food and do that safely and so forth.

So there’s really cool aspects to it, even though there’s aspects that are like, as you say, it’s a trade-off.

And you do have to think about those resources.

So I think I always want to always ask people who ask me that question, like, where do you think the best money is for an analog mission?

And what is the best bang for our buck?

How can we actually send people to these places as safely as possible to keep the public happy because we don’t want to hurt people, but we actually have to take risk to get to places like Mars?

I think it’s a tremendous exercise in risk management.

I mean, it’s so worth it.

NASA has been very good about that ever since its founding years.

By the way, you mentioned Chris Hatfield, the Canadian astronaut, probably the most famous Canadian astronaut, and he’s been a guest on StarTalk.

Yes, he has.

Yeah, we even had him play his guitar, as he did in space.

And says, as I said, leave your guitar at home.

Stop!

I’m not even gonna lie.

So Kelly, we gotta call it quits there.

It’s been a delight to have you on here.

And when you get all, when all three missions are done, you’re not gonna repeat, right?

No, although I would love to do like a different form.

Like I’d like to go to Antarctica next and like try out an analog there.

Cause like, that’s a different kind of analog.

And it would be super cool to contrast that.

You are the only person I have ever heard in my life say, I’d love to spend a year in Antarctica.

You’re cut from a different jib there.

Just got the right amount of crazy.

I’m telling you, I’m glad you’re on our side.

We are reminded here that while you can read about a discovery, especially if it involves humans, achieving some goal that has been set forth by others, be it the general population or governments or whatever, and you can celebrate the results, but somewhere in there, homework was done.

There were people who came before, scientists, engineers, test subjects, and you don’t always read about them.

You don’t always read about the hard work that went in to prep the final steps that are taken by those who get all the media attention.

And so it reminds me of how fundamental that is.

If you’re gonna move the frontier, but you want to do it sensibly and safely, there are these unsung heroes who actually empowered that in the first place.

And I try to never lose sight of that.

Yeah, we had Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walk down the moon.

Anytime I’ve said that, I’ve said, they’re not the only ones who walked on the moon.

So did 10,000 scientists and engineers and 200 million taxpayers.

We all walked on the moon that day.

So, just delighted to hear about these early steps and to just get a taste of how you make that sausage so that it tastes good in the end.

Commander Kelly, thanks for being a guest on StarTalk.

Thank you so much.

It was a real honor to be here.

And I just want to give a shout out to my crew and also the Chopea ground team, who were an amazing group of people that put this experiment on.

The ground team whose schedule you matched.

We’ll start a movement so that that doesn’t happen in the future.

Yes, exactly.

Thank you.

Because it only takes a month to go completely out of cycle with…

If you’re off by 30 minutes, a month, you’re 12 hours.

Anyhow, we’re good here.

Again, Commander Kelly, thanks for being a guest.

Thank you so much.

Chuck, always good to have you, man.

Always a pleasure.

This has been StarTalk, Neil deGrasse Tyson, as always, bidding you to keep looking up.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron