About This Episode

Could life hitchhike across planets? What color is the sky on Mars? Neil deGrasse Tyson and Bill Nye, the current CEO of the Planetary Society, team up to discuss the science and advocacy that goes into space exploration, unraveling the threads of discovery that define humanity’s quest to understand the cosmos.

Bill and Neil discuss the tantalizing possibility of life beneath Europa’s frozen surface, where a 4.5-billion-year-old ocean may hide secrets of alien biology. Why is this moon one of the most promising sites for life in the solar system? We explore comparative planetology and how studying Venus’s greenhouse effect helped us learn about Earth.

From the groundbreaking Voyager missions to the role of cameras in space exploration, we explore some of the pivotal moments that shaped our view of the universe. Why did Bruce Murray, a co-founder of The Planetary Society, insist spacecraft carry cameras? Learn about Carl Sagan’s goal to connect the public to space exploration and how space advocacy led to the launch of the solar LightSail.

And what about the search for life? From the SETI program’s hunt for intelligent signals to the possibility of Martian panspermia, the episode explores the big questions driving today’s research. Once life begins, can it ever truly stop? Bill and Neil explore how The Planetary Society continues to push the boundaries of what’s possible in space, led by science, passion, and an unrelenting Joy of Discovery (JOD).

Thanks to our friends at The Planetary Society for partnering with us on this episode! To support their mission and the future of space advocacy, head over to Planetary.org/StarTalk!

Thanks to our Patrons Edwin Strode, Mathew M, Micheal McDonough, Evan Fenwick, Trvis Knop, David Hardison, Sarah Kominek, Saulius Alminas, Rob Lentini, Eric Williams, Billy, John Buzzotta, Jeremy Hopcroft, Christian Harvey, Bob Cobourn, Jeremy Alford, Brandon Cortazar, James Finlay, Anastine2020, Rebecca Valenti, jordan battleson, Timothy Jarvis, and Gleb Mpakopuc for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTWelcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk.

Neil deGrasse Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist.

And today, I’ve got an exclusive one-on-one conversation reserved for only those people who are not only important but are also a friend of mine.

We’ve got with me in studio Bill Nye.

Greetings, doctor.

How are you doing, man?

You’ve got a bow tie on and everything.

You’re just completely that guy.

I am that guy.

The science guy.

What you see is what you get.

And did you tie your own bow tie today?

Yeah.

Can you imagine?

Bill Nye wears clip-on ties.

That would be a funny skit.

Bill Nye decided to end his career and lose respect from all his fans.

I want you to know, if I ever see anybody with a bow tie, I ask them if it’s real.

And if they say not, which is about two-thirds of people…

Not?

See what he did there?

I say, I’m going to tell Bill Nye on you.

And then they shudder because they…

They can wear clip-on bow ties.

That’s fine.

I mean, I just think it’s not, as we say, the spirit of the game.

I flew my ass out here to Los Angeles.

We are now in your office of The Planetary Society, Pasadena, California, the same town where this society was birthed.

A true fact, not a false fact.

So give me a fast birther story on this.

So Carl Sagan had been very influential in getting Voyager, the Viking landing on Mars and the two Voyager spacecraft launched.

And just for historical completeness, there were two missions of Viking lander and a Viking orbiter, and so it could photograph the surface.

Yes, amazing, really amazing visionary ideas.

And so he noticed that public interest in space exploration, especially planetary exploration, was very high, but government support of it was waning.

And he had this big idea for a solar sail spacecraft.

It’s the 1970s now.

1976, yeah, and the disco era.

And that was set aside for more human missions, including the famous handshake in space, so that the Soviet Union and the United States would have no more conflict, and that worked out great.

It was an Apollo capsule in orbit around Earth, the Soyuz capsule, and they were configured so that their collars could join, and they opened the hatch, and they’re all weightless, so they’re just floating through, and they would shake hands.

And I was told that the Americans were trained to only speak Russian, and the Russians were trained to only speak English.

And US astronauts still speak Russian.

It’s still a thing they do.

So we flew on Soyuz rockets for a zillion years.

All that inclusive.

Bruce Murray, who was head of the Jet Propulsion Lab during these famous missions, Viking and Voyager.

The Propulsion Lab right here in Pasadena.

Yes, right at the rival up the street.

And then Lou Friedman, who was an orbital mechanics guy.

Engineer.

Yes, at both a PhD, which you like.

They decided that there was enough interest in space exploration that they could start the Planetary Society.

And of grassroots interest.

Grassroots.

So we had, the Planetary Society had tens of thousands of members by the end of, pick a number, 1982, was started in the winter of 79, 1980.

I’m a charter member.

Now, I remember getting the letter.

And I was not, I’ll be frank with you, I was not moved by the letter.

Because if I remember correctly, it says, Dear Citizen of Planet Earth.

And I said, that’s not very special to me.

What did you want?

Citizen of New York.

Dear Neil, I mean, I don’t know.

Something a little more personal than Dear Citizen of Planet Earth.

It was the state of the art.

Anyway, the Planetary Society has been around now, they will have our 45th anniversary this spring.

And what we do is promote planetary exploration.

And just notably, just last week as we’re recording this, the Europa Clipper mission left for the moon of Jupiter with twice as much ocean water as Earth.

And that is, in part, let’s say entirely, because of the Planetary Society, where our members, 40,000 people around the world, think space exploration of planets is very important, wrote letters and emails to US Congress especially, got this mission funded 11 years ago, and now it’s flying.

And it was delayed because of Hurricane Milton.

Hurricane Milton.

You know what I wanted?

I have a little sort of romantic nostalgia for the 1969 film Marooned.

Do you remember that film?

Yeah, with OJ.

Simpson.

No, that’s a different, no, he was not in that movie.

What’s that one?

You’re getting your movies mixed up.

That was Capricorn 5.

Capricorn 5.

Okay.

Capricorn 5 or Capricorn 1?

Oh, maybe Capricorn 1.

Yeah, yeah.

Anyway, Marooned, where the retro rockets don’t fire, and they keep clicking the button.

So they can’t get out of orbit.

Yeah.

All right, but they have a rescue ship to go rescue them, but they can’t launch because a hurricane is coming through Cape Canaveral.

Those were the days.

Okay.

And I remember as a kid, it was like, hurricane, that’s pretty artificial.

Storytelling.

Yeah.

It’s Florida.

This was not a weird fact to put into your story.

And so then some clever meteorologist said, hey, Neil, the eye of the hurricane is going to go over the launch pad.

Have you seen, have you ever been in the eye of a hurricane?

I’m told it’s really eerie.

It’s weird.

Yeah.

I was at Hurricane Agnes in the early 1970s.

Came over and all of a sudden it’s a clear sky for a little while.

And I’m told there are birds that get trapped inside of the eye of the hurricane, like tropical birds that end up thousands of miles away from there.

It would have been cool had they launched, and you rope a clipper in the eye of the hurricane.

That would have been a risky set of businesses because the…

The window is big enough.

They just delayed it a week.

Well, not just that.

Just keep in mind, everybody, humans have to be there to launch the thing.

Like people have to go home, they have to secure, they’ve got to screw plywood to the windows of their house, and then they have to come back to the Cape to be ready to push the button and look at all the fuel lines and liquid oxygen connections and all that.

That there’s a lot more to it when we talk about spacecraft.

We remind everybody there are a tremendous number of assets and investments in the infrastructure on the ground.

Back to you.

Has the mission statement changed over the decades?

Very little, but it’s succinct now.

We are the world’s largest independent space interest organization, advancing space science and exploration, so that citizens of Earth will be empowered to know the cosmos and our place within it.

That’s really catchy, you know.

Well, here’s what it is.

It’s succinct.

We empower citizens.

I agree.

I’m just saying it doesn’t roll off the tongue.

Well, it does if you’re the CEO before the elevator doors close.

You are CEO and president.

No, no.

There’s a bylaw rule.

I’m not president.

What are you?

We have a separate, I’m CEO.

Just CEO.

Yeah.

I thought you were important.

Exactly.

So the president is an unpaid position.

Did not know that.

Yeah, that’s a great tradition here at a nonprofit in California.

You used to be president.

I used to be vice president.

Vice president.

Okay.

I was equally unpaid as vice president.

And so the board of directors is committed.

And just notice everybody, our board is the real deal bunch of people.

Our president is Bethy Elman.

Dr.

Elman is a professor at Caltech.

She has a couple of missions that she’s a principal investigator, a PI on.

And our vice president, Heidi Hammel, is one of the 20 most influential women astronomers in history.

Brittany Schmidt is driving around submarines under the ice in Antarctica to prepare to go under the ice on Europa and Titan, or Enceladus, I mean, I was joking, Enceladus.

One of the moons of Saturn, another icy moon.

Icy moon.

And so everybody, if you have ocean water for four and a half billion years, is there something alive under the ice?

It happened here on Earth.

One of the defining missions of the 1970s was the Voyager.

Oh, it still defines people.

I don’t know if it’s wide enough to see, but there’s a replica of the record.

Uh-huh, so this defined a generation of hope for our future of space exploration.

And Carl Sagan was particularly visible and known over that time.

Yes.

Yeah, has it changed over the decades?

And I ask that because if I remember correctly, because I used to serve on the board of the Planetary Society, and I cherish those years, because it’s where I met you.

And it’s where I met Ann Drouian, Carl Sagan’s widow.

I did not know either.

I might have met her once or something, but we didn’t know each other until we were both on the board.

So these are important connections to be made.

This is what we do.

We connect people with the passion, beauty and joy, the PB&J.

PB&J, loving it.

That’s Bill Nye-ism, PB&J.

Yeah, but it’s really caught on in the science education.

This is, that’s how…

But now, all that aside, peanut butter and jelly used to be a very common lunch treat.

I remember there was a resistance to people in space relative to robots.

And some of that might have just been the sphere of influence of Carl, Carl Sagan, where he just, who’s a robot guy.

From an engineering or scientific or science fiction critic of astrophysical observer…

Which I count myself among the ranks of.

Yes, premier astrophysical observer.

Note well, you can’t get people to Europa.

It’s too flippin far away and too cold and there’s nowhere to walk and everybody’s gonna die.

So you build spacecraft to go there as our proxies that we design the instruments to be as human, to give us both a scientific perspective and a human perspective.

But in the day, robots were nothing compared to today.

In the day, I mean, 50 years ago, computer robots then to today.

Today, I’m walking down the street.

In LA., there’s a car with no driver.

Yes.

No driver!

They’re making left turns, it’s the turn to going straight.

You may see the bumper sticker here in California on the Tesla that says, I’m probably not driving.

That’s pretty charming.

But note well.

Okay, so these are robots.

It’s a car robot in that sense, right?

Yes, that’s what I’m saying.

What do you got here?

So this is the Spirit Rover, a picture of the Spirit Rover, and the cameras.

And it’s solar panels.

Yes, the cameras were set up to be, this is the expression, as high as a 10-year-old’s eye.

So that you were, these cameras were put there so that humankind could imagine ourselves walking around, driving around on Mars.

And talking about the Planetary Society, the lore that we promote, and I think you alluded to this earlier, is that Bruce Murray was a young guy in the 1960s.

Co-founder on working on the Mariner program.

Mariner to Mars.

Mars, which was the Ranger spacecraft repurposed to go…

Ranger went to the moon to map the moon.

And as a kid, I was being class, and we watched the moon come up.

Yeah, ships in space, no sound.

Yeah, some of the Rangers crash landed.

Yeah, on purpose, purposefully.

And to see what the lunar surface was like up close.

So I forgot all about Mariner, because Mariner, I think, took the first pictures of Mars that revealed there were no canals.

Yeah, and so this Bruce Murray gets credit when you’re talking to us at the Planetary Society for being the guy who insisted that spacecraft have cameras.

Because people think scientists love pictures, but we don’t give a rat’s ass about a picture.

Well, it depends on the picture.

No, what I mean is there’s much less science in a photo than the public is led to believe.

We get chart recorders, we get magnetic, magnetometers, Geiger counters, magnetometers, magnetometers, spectra, we got a lot of optical.

Give me a spectra over a photo any day.

But if people get do-eyed about how beautiful the universe is, it changes the world.

Pictures from space change the world.

We all at some point must confess to ourselves that that is the fact.

Confess your brains out.

If we want to credit back to some of these founding fathers, I think Carl Sagan was the first scientist in his writings and in his appearances on television, and to put you, just a regular person.

A regular person, citizen of Earth.

You became a participant on that frontier.

It was no longer, let them go do their thing, and they’ll report back later.

No.

Or spend some tax dollars on this.

It probably doesn’t have anything to do with you.

That’s not a chance.

It all has something to do with you.

Everything, you are part of this great process of discovery, this adventure.

And Bruce Murray used to talk about the unknown horizon.

Why are you guys sending spacecraft out to these extraordinary distant places?

What are you going to find?

We don’t know what we’re going to find.

That’s why we’re sending the spacecraft.

I think it’s Einstein that’s famously said, research is what I’m doing when I don’t know what I’m doing.

That sounds good.

Yeah, that’s completely it.

Isaac Asimov, science doesn’t begin with a hypothesis.

It begins with, that’s funny.

Oh no, you got that wrong.

Oh, he helped me out.

Yeah, he said, very few scientific discoveries, if any, ever begin with eureka.

It’s, that’s funny.

That’s funny.

What is that?

So we explore the planets.

So another thing I credit the Planetary Society for, and its philosophies, and its outlook, is turning objects in space into worlds.

Worlds is a great word.

When you use the word world, it’s no longer a detached object from your imagination.

It really gets you here.

You got it, man.

You hit the, no, Neil, that’s absolutely right.

I don’t know anyone else who, any other…

Organization.

Organization or worldview that made that such an important point.

Right on, man.

So you guys, you should join the Planetary Society.

Another thing that I credit the enthusiasm of the Planetary Society for is when I was growing up, the moons of planets, like, why wouldn’t anyone give a rat’s ass?

It’s the moon.

Look at the planet, not the moons.

And then Voyager goes out there, gets pictures of the moons and the moons are more interesting than the planets.

A lot going on.

A lot.

They’re all different.

Io, Europa, Ganymede.

Our moon is like the least interesting moon in the solar system.

What’s interesting about the moon is it’s got a far side and a near side.

That to me is amazing.

And I asked Carl Sagan, why is the near side relatively smooth?

I asked him this, as we say in middle school, to his face.

And he said it’s the Earth’s gravity enabled these impacts to get this focusing get accelerated.

Yeah.

And so lava flowed more recently on the near surface than the far surface.

Did that turn out to be true?

You tell me astrophysics, gravity guy.

I’ve seen your gravity books, man.

I dabbled in the three bodies.

I dabbled in the Hamiltonian.

I think there’s an argument that any asteroid that’s headed in our direction would feel Earth’s gravity and it would you’d have a focusing effect towards.

So Sagan back then said gravitational lens, which was, that’s not how the term is used, but we got to all get through it.

Yeah, yeah.

No, your words include more than they leave out.

So planets become more interesting.

Moons become places to go and revisit, but there was a whole other, a whole other goal, and that was the search for intelligent life.

It still is.

In the universe.

Oh, man.

And I’m remembering how big a part of that was in my couple of years when I served on the board.

But then when I came off the board, it’s less tangible, right?

Because we don’t know if the aliens are out there and are they hearing, listening to us.

So where is TPS, the Planetary Society, relative to the search for intelligence?

Well, we’ve let that go to this SETI Institute.

SETI Institute, of course.

SETI Intelligence Institute.

And they’re based up in Northern California.

Yeah, yeah.

And they’re very well endowed and they chip away at this problem.

And they just got a boatload of money just recently.

Well, I went with well endowed, you can go boatload of money.

Spacecraft full of money.

And so they will carry on.

A barge full of money.

A barge full of money.

They will carry on that research in their enabled best way possible.

And they have a whole suite of telescopes originally funded by Paul Allen, the Allen Array.

So these are telescopes that are sensitive to radio waves on the assumption that if anyone is going to talk to us, so they’re going to use radio waves because radios penetrate clouds.

Carl Sagan was very well spoken about this, about this logical place where water molecules would not absorb radio waves, logical place, logical frequency, where radio waves would not be absorbed by water vapor.

And so, if an alien civilization was…

This is water vapor across the universe as well.

Hydrogens everywhere, you could aim your intergalactic or interplanetary interstellar, interstellar message to go through the water hole, as he called it.

Very well, very cool term.

But all that aside, it is very reasonable that, maybe in my lifetime, but in your kid’s lifetime, somebody’s gonna find evidence of life on another world.

And the logical places are gonna be under the sands of Mars.

Okay, but this would be microbial life.

This is not, you know, little green.

But still, it would change the world.

Then you would say to Mr.

Microbe, Ms.

Microbe, they, Microbe, do you have DNA?

Are you a whole nother different?

I get that, but that wasn’t what SETI was about.

No, no, it’s still not.

Right.

SETI finding microbes, that’s not their…

That’s fine.

Knock yourselves out.

That’s not their thing.

And because if we found such a signal, it would, dare I say it, change the world.

And so SETI Institute keeps listening.

We had an exhibit at the Hayden Planetarium before we rebuilt that was narrated by William Shatner and it was about the search for life.

And I remembered the quote because I thought it was a brilliant sentence.

He said it in his sort of pause acting way.

The day we discover life will signal a change in the human condition that we cannot foresee or imagine.

Do, do, do, do, do, do, do.

That’s pretty good.

No, everybody, I say all the time, everybody will feel differently about being a living thing.

Yes, whether or not it’s what we call intelligent.

Oh yeah, it would transform biology.

The logical question from the sands of Mars, there’s another hypothesis that once life starts, you can’t stop it.

So if life started on Mars, there’s salty slush near the equator of Mars.

We kept almost warm by the sun.

Are there microbes living under the sand?

And if we found them, do they have DNA?

To wit, was Mars hit with an impactor, which happens all the time?

Long ago.

Knocked a living thing on a rock off into space.

It fell, except in space, no sound.

These would be microbes stowing away in the nooks and crannies.

Trapped, stowing away.

Land on Earth.

And you and I are descendants of Martians.

That is an extraordinary hypothesis.

I think you more so than me.

Yeah, well, it’s an extraordinary hypothesis, but if it proved to be true, it would change the world.

And so it is worth…

That would be panspermia.

Panspermia, it’s worth investigating.

And I just discourage all of you out there who want to go to Mars by yourselves on your own giant rocket.

Just don’t go to the same places.

The same places that are interesting to you may be or are very likely the same places that are interesting to people studying astrobiology.

That’s just for anybody who happened to…

Just anybody who happened to used to be on the board of the Planetary Society before he or she was being sued by the Securities and Exchange Commission is trying some political tactic to try to not try to get a pardon someday.

If you are that person, consider doing it a different way.

It could be one of a number of people for sure.

Yes.

There’s nothing specific there.

In the Viking missions, famously, the rocks came back, those pictures, depicted the Martian sky as blue.

And the rocks were too pink.

And it took them, I was at the 30th anniversary of this thing, and these guys were talking about, it took them about a day and a half to realize that the cameras had been calibrated on Earth, and the pictures needed to be recalibrated.

So they found intuitively that if you look at the shadow, you can infer the color of the sky.

So those of you out there haven’t sat through this, go outside on a sunny day.

If you’re in Ithaca, New York, where I went to college, there is a sunny day scheduled in the next 10 years.

Then you make a shadow on something white, like my shirt would be good, and you’ll see the shadow is gray, to be sure, but it’s also ever so slightly light blue.

And that’s because the sun is not the only source of light here on Earth’s surface.

The sky is a source of light.

Looking at me, nothing but orange skies on the other planet.

Yeah, so on Mars, the sky is orange, or salmon-colored, or what have you.

And so they’ve found that by looking at the shadow, they could infer the color of the sky and then how much the colors of the rocks had been influenced on the camera, on the images, by the color of the sky.

That’s very clever.

So what you’re saying is, to summarize, whatever’s going on in the shadow is not directly influenced by the sun.

It’s directly influenced, but it’s not the only influence.

Sorry, you get an authentic background lighting from the rest of the sky.

Yeah.

Yeah.

So let’s send a shadow caster to Mars.

I was in a meeting at Cornell.

A strato caster?

That’s a guitar.

That’s the blues guitar, and I don’t know if you are a strato caster or master, but the idea was to send this post, the stick, to Mars to cast a shadow.

And I was in the meeting and I said, aren’t there many, many things to cast a shadow?

No, we need it to fall in something precisely calibrated or well-known colors or gray scale.

And so I was in the meeting.

Now, my dad had the misfortune of being a prisoner of war in World War II for almost four years.

And he told the story often of walking in…

In Japan?

In China at first and then Japan at the end of the war.

They got, as Japanese influence shrunk, they got moved to the South Island of Japan for the last year of the war.

But he would, by all accounts, stick a shovel handle in the soil and watch the shadow and reckon when it was lunchtime kind of thing.

And so he came back.

It’s a sundial of him.

That’s right.

So he wrote a book about sundials.

He was the Astronomy Merit Badge Counselor.

He made a sundial.

That would be for the Boy Scouts.

For the Boy Scouts.

So I was in the meeting.

They’re gonna send a metal stick to Mars to cast a shadow.

So you have genetic probability.

I’m just jumping out of my chair.

You guys, we gotta make that into a sundial.

Okay, I’m glad you didn’t put a shovel here for this.

So they were all looking at me like, dude, it’s the space program.

Bill, I see you’re wearing a watch.

No, come on.

It’ll be like people who speak Klingon, except it’ll be real.

Mars, 2004, two worlds, one sun.

That’s so Lou Friedman, one of our founders came up with that.

We were having dinner at a place that’s now, it was Louise Trotteria, now it’s Cheesecake Factory.

But he said, one sun, two worlds.

In a few seconds, we all went, oh, no, no, two worlds, one sun.

That’s really inspirational.

Light, shadows on Mars are cast by the same life-giving star as shadows on Earth.

Now, wait, wait, there’s more.

On the edge, around the dial is a message to the future.

We built this instrument in 2003.

It arrived here in 2004 to study the Martian environment and look for signs of water and life.

And on the last of the four panels…

I can’t read this.

What is it?

Is it in Braille?

What is it?

It’s in a younger person’s font.

Yeah.

Okay.

That’s what it is.

It says, on the last of the four, it says, to those who visit here, we wish a safe journey and the joy of discovery.

And that’s written in English, because, of course, aliens read English.

English, no, no, it’s written for humans.

Oh, other humans who arrive.

English is the language of aerospace, even now.

And so…

And of aviation, too.

Yeah, aviation, yeah.

So, it’s optimistic.

People are going to be there, and they’re going to go up to that thing and look at it and think about the people…

The way we go up to the Plymouth Rock.

The way we go up to what have you.

Yes.

A pyramid, a Michu Picchu.

We go up and go, wow, that’s an extraordinary thing humans before us did.

And it’s optimistic, and it has the joy of discovery.

And that has become PB&J, Kashmudenjoy, J-O-D, joy of discovery.

That’s become a phrase with me and the staff.

Tell me about literal political advocacy, because it’s one thing to just celebrate it, but at some point, somebody’s got to show up in Washington.

This is what we do.

So, we’ve been asked to testify?

Oh, heck yes.

So, what we have been able to do is hire two guys who are just really into this and are excellent at it.

So, we have one guy who studies policy.

This sounds like you’re talking about lobbyists.

No.

So, lobby, a lobbyist is a paid person and he has to have a license in this and that.

We are advocates.

So what we do is get our members, 40 plus members around the world.

Thousand.

40,000 members around the world, well said.

40K, 40 plus K, close to 50K people around the world.

This is evidence I’m paying attention to what you’re saying.

Yes, thank you.

I just want you to know that.

That’s why I interrupt you when I pay attention.

I appreciate it, Neil.

It’s very appreciated much.

The 40 members of the Planetary Society.

40,000 members plus almost 50,000.

Some weeks it is over 50.

We have this non-profit problem continually.

People fall off, you have to re-engage them.

They fall off the ring.

All right.

All that aside, we send letters and emails to members of Congress and the Senate advocating for space missions that we believe are in the best interest of humankind and the best interest of making discoveries on these other worlds that will affect our world.

And the one that we are all talking about this week is the Europa Clipper, a replica shown here.

Because it launched.

Right.

And I testified in front of Congress in 2013 about the importance of this mission, where we are looking for signs of life on another world and or organic material on another world to learn more about our own world.

And we do it for inspirational, wonderful joy of discoveries, reasons.

But it’s also, if you want to be the world leader in technology, you invest in space exploration.

I testified once, but I felt like it was going to a black hole.

Well, that’s a black hole.

See what he did there?

But I wasn’t representing a whole organization as you are.

Well, that’s what I say.

That’s a different force operating.

Plus, I’m one voice, and my voice is not irrelevant, to be sure.

It’s relevant.

But when these congressmen and senators get thousands, tens of thousands of 10Ks of letters and emails, it affects them.

You at the helm of this ship that has influence.

When I testified, I’m just Neil talking to the Congress.

And do they, you know, what am I doing here?

That’s what they said to, everybody said to me, Neil, behind your, behind your back.

No, so.

But I look at this list here, because it’s not just Europa Clipper, which is successfully on route.

It’s just most recent.

Hubble, Mars sample return, the New Horizons to Pluto, the Europa Clipper, of course.

I got two other missions here.

Veritas, which means truth, but that’s all I know about it.

And Viper, what are those?

So Veritas is a mission to Venus.

So I haven’t had a mission to Venus in 40 years.

It’s not entirely hospitable.

Oh, well, but you want to have a look and see what happened on Venus.

What happened on Venus, we don’t want to happen on Earth.

In fact, people talk about climate change now, regularly.

As you know, I’ve been whining about it for a long time.

You’ve got a whole book.

What’s the name of that book?

Undeniable, perhaps.

Undeniable, yes.

A whole book talking about the reality of climate change and how to spread that information against misinformation.

Misinformation, largely from fossil fuel industry, who’s worked hard to make scientific uncertainty the same as doubt about the whole thing.

But that aside, you can argue that climate change on Earth was discovered by studying the atmosphere of Venus.

And so in 1984 or so, so this is really an extraordinary thing.

It’s this classic Bruce Murray.

What are you going to find when you go exploring these other worlds?

We don’t know.

That’s why we go exploring.

So, Bill, what you just said reminds me of that quote from TS.

Eliot, where he says, I’m going to mangle it, but the essence of it will be there.

You explore the world, you know, see new places, travel, travel, travel.

And then you come back home, and only then will you know that place for the very first time.

As I say, the more we explore these other worlds, the more we know about our own.

That’s that, is it a new field?

Comparative planetology.

Carl Sagan used to toss that phrase around like it was a real phrase.

It’s not like we’re here and everything else is something else.

That’s right.

Plus, can I tell you, one time I was delightfully out geeked.

You’re pretty, when you are geek Neil, you’re geeking pretty hard.

But geeks, you know, geeks are on an unlimited spectrum, okay?

However geeky you are, there’s someone geekier than you.

Particularly if you go to Comic Con.

Arms reach, shake a stick, there’s someone geekier.

All right.

So I calculated how long it would take to cook a 16-inch pepperoni pizza on your windowsill on Venus.

On your windowsill?

Yeah, you just put it out on the windowsill, you know, close the window and just let it cook.

It’s pretty quick.

It would take seven seconds.

Seven seconds.

OK.

All right.

So not only is it cook in seven seconds because of the temperature, did you take into account atmospheric pressure?

Yes.

Yeah.

In my calculation, I considered, as you suggested, what is the temperature of the air and how many air molecules are hitting it because it’s got ten times the pressure that we have here on Earth.

That’s all factored in.

All right.

That’s how I got down to seven seconds.

So bubbling pizza is hardly going to bubble.

Okay, so I then got out geeked.

Someone said, Neil, did you consider the thermodynamic radiative layer within the atmosphere?

It’s the optical depth.

It’s the distance over which a photon is no longer absorbed by the air and it goes to your target.

I said, no, I hadn’t.

That’s important.

It’s why when you’re in front of a fireplace and someone walks in front of it, you feel cold immediately.

Yes.

That’s not the air temperature changing.

And so I had neglected the radiative factor from the hot atmosphere.

So how long does it really take?

Two and a half seconds.

Two and a half.

It’s three times faster.

It’s pretty fast.

So yeah, if you got to get out, geese are going to be in there.

So if you’re there with your pizza and you have some means to open a window without exploding, dying, getting cooked, I’ll keep that in mind.

But these are important thought experiments because they’re physics.

Yes.

All science is either physics.

Yes.

Or stamp collecting.

So we got to land this plane.

Oh, man.

OK, so a couple of things.

Are we going to tail first, propulsively land?

Are we going to go in, you know?

We’re going to glider.

I’m a glider, lander guy.

So I don’t want to splash in the ocean.

That’s very primitive.

But it’s hard to miss.

That’s why they did it.

That’s why they did it.

The Pacific is a big target.

Well, and so is off the coast of Florida.

Now, I don’t know if you remember this, but when I was young, the spacecraft was in 10 miles of the Navy ship.

That was a big deal.

Now they, wait, don’t get too close.

No, you landed on the right side.

Yeah, yeah, back to you.

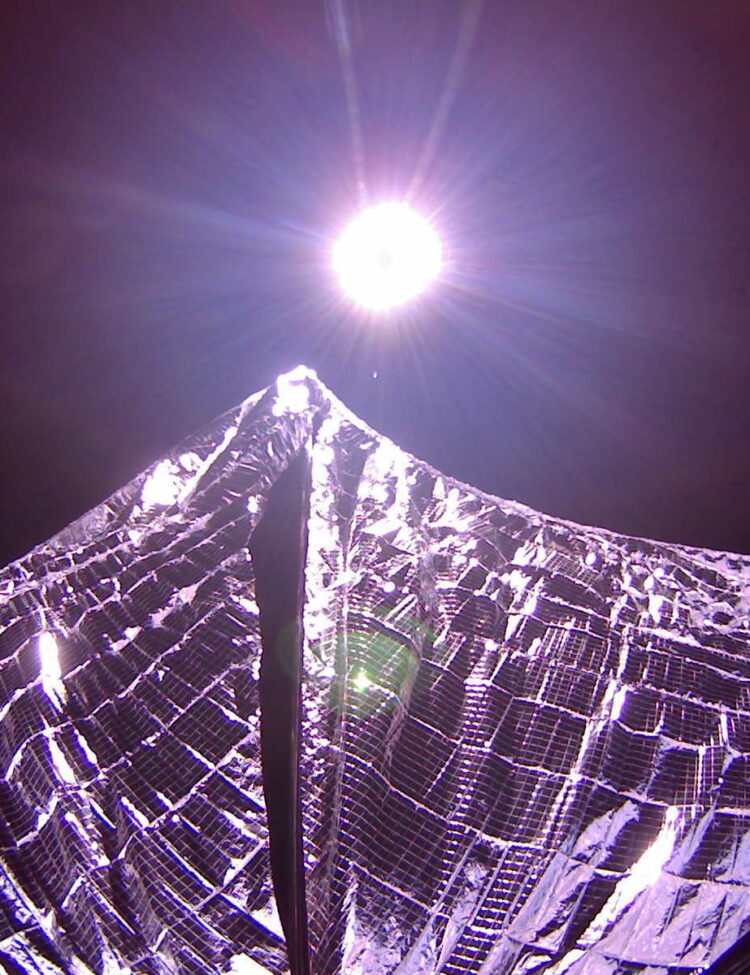

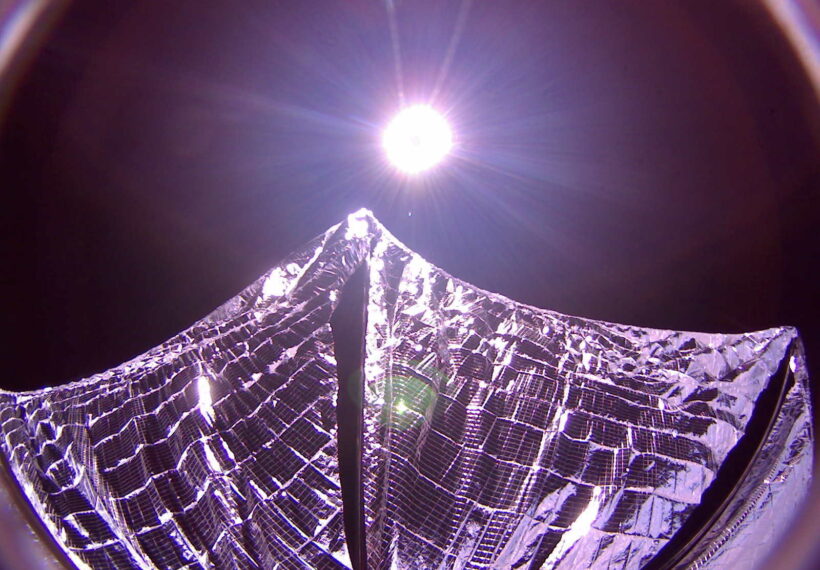

So, another big part of the Planetary Society’s identity was the successful funding, appeal funding and launch and deployment of the solar sail, which was the dream of so many people.

One of your founders, Lou Freeman, wrote a book.

Yes.

And so this was like a very big expression.

Andruyan was a big proponent of this.

Andruyan Carl Sagan’s widow and board member.

So would you count that as among the bigger achievements?

Oh, yeah, especially under my watch.

No, really.

We had a solar sail launch funded largely by Andruyan and people associated with the Discovery Channel.

And it crashed in the ocean.

And it was okay.

Game over.

Done.

Boom.

So then it took many years, nine more years, to get it together to build another spacecraft.

And in that interim, this thing called the CubeSat emerged, cubical satellite, which are 10 cm by 10 cm by 10 cm.

And then variations of that have been created.

You can go online and buy parts for satellites.

And they’re cheap to launch.

Very inexpensive.

It’s like your science project.

Yeah, it is.

And a lot of students, a lot of universities and high schools participate in CubeSat programs.

And the other thing is electronics have gotten increasingly smaller, more miniaturized.

One could argue that the miniaturization of electronics was stimulated by space.

Yes.

Well, it’s, how to say, symbiotic.

Yeah.

We were able to get funding.

50,000 people around the world just think it’s great.

We launched a spacecraft in 2014 to prove that it would work.

And by the way, I’ve done very little as CEO.

The place is run by Jennifer Vaughan, our chief operating officer.

We have a chief financial officer, Jim So.

We have chief of communications, Daniel Gunn.

We got a development officer.

We got all these people.

But once in a while, somebody’s got to decide to do something.

So it was my decision, should we take this launch in 2014 with a spacecraft that wasn’t as capable as we hoped one day would be, but it had cameras.

And so we launched in 2014.

We got these pictures down.

And that enabled us to get funding to launch Lightsail 2.

There it is.

You could see the Lightsail unfurling.

Am I remembering this?

That makes it very real.

So by the way, so right there is a boom.

That golden looking thing is beryllium copper.

And what’s cool about it or remarkable, this is the same material in much shorter length.

Just notice how stiff it is if you try to bend it.

Yeah, it can.

And then notice how compact it is if you try to roll it or bend it in the other axis.

And so this is what enables these.

You fold it up to get into the fairing.

Well rolled up.

Yeah, and if you look at it, there’s these tiny dots.

These are laser stitch welded at the US Air Force Research Lab.

Anyway, I mention all this because there’s a lot of cool technology that we perfected and flew in 2017.

As any good space mission does, because you’re doing something that’s never been done before.

Never been done before.

Somebody’s got to innovate.

Yep, had to innovate.

The control laws, how you steer it, and rolling it up, and getting it robust enough to tolerate cosmic rays without being too heavy to fly.

We did all that.

And so very proud of that.

And people ask us, what’s next?

I’ll just say stay tuned.

So a quick, I want to remind people, unless they’ve been living under a rock, many people, you taught them science growing up as Bill Nye the Science Guy.

It really is amazing.

And now they’re full grown adults with kids, and some of them have kids, and you’re like, Papa Science here.

Yeah.

And you were the heir apparent to what maybe was in our generation, who’s the guy on TV?

Don Herbert.

Yeah, Don Herbert.

I had lunch with him.

I look like nobody, I had lunch with him.

Don Herbert, and he was Mr.

What was he?

Mr.

Wizard.

Mr.

Wizard.

Are you following with me, Mr.

Wizard?

So I went to his memorial service.

And you guys, I was just crying.

I just couldn’t get over it, man.

The guy was so influential.

I can tell you the technical aspects of everything, but his show was done intuitively.

The Science Guys Show, we had all this research that 10 years old is as old as you can be to get the so-called lifelong passion for science.

To get it when you.

So it was dialed in.

I was nine.

I was nine.

I love you, man.

Yeah.

It was dialed in for people 10 years old.

That’s why, that’s part of why the show was so successful.

And then you would, I don’t want to say transition out of that, but you added to your professional profile.

Added, yes.

Yes.

To be a space advocate, like for adults and for the nation and for the president.

For the world.

This sort of thing, yeah.

And did you ride in Air Force One one time?

Yeah.

Excuse me.

Barack Obama got to meet me.

Yeah.

And spent some time.

Did you chill in with Barack, there you go.

But he is a very thoughtful and frankly charming guy.

And smart, yeah.

And so I, well he’s brilliant.

And so we talked about space exploration on Marine One.

I know you’ve hung out with them, but I, it was quite cool and he is very receptive to addressing climate change.

He was very interested in that.

And his policies led to this, the beginning of the start of a beginning of climate policies involved in the Inflation Reduction Act, aka the Clean Power Program.

Which had some elements to it, yeah, yeah, yeah.

So, Bill.

Neil.

Planetary Society.

Great to see you.

So, where do we find it?

You got a website for it?

planetary.org, it’s your home page.

planetary.org.

planetary.org.

Okay.

And we have a podcast.

Is there some big button there that you can join?

Yes, and so on every page, if you guys want to run a nonprofit, you put a donate button on every page.

Right, that’s what it is.

And so we thank everybody out there who is a member, encourage those of you who for some reason are not members to join us and we have now the Planetary Academy aimed at families.

And the monthly Planetary Report.

Planetary, it’s every four times a year now because people get their space information on the electric internet.

So we have longer form articles in the printed magazine.

Rather than journalistic articles, which we have some of each.

We have, I claim, we have the world’s premier long form planetary science journalism.

Nice.

But I myself have referenced it to catch up on certain elements.

Yes, well thank you.

Yes, we have the best reporters going.

Because mission information is very fragmented.

It is everywhere.

There’s a little bit there and a little bit there.

And it comes into a coherent, sensible pedagogical delivery.

To give us an idea of what’s involved, you want to go, you send a mission to Jupiter, big, enormous rocket, Falcon heavy, three Falcon 9 strapped together, 27 engines blasting at once, going as fast as you can, getting a sling shot from Earth takes almost six years.

And so you’re in this game for the long haul.

And with Europa Clipper, we’re six years out.

That’s what I’m saying.

Five and a half years.

That’s what you described.

Yeah, yeah.

And just it will change the world.

Thank you all.

planetary.org.

Turn it up loud.

This has been my exclusive conversation with the one and only Bill Nye the Science Guy.

Oh yeah.

Tune in next time for our next episode of StarTalk.

And until then, as always, keep looking up.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron