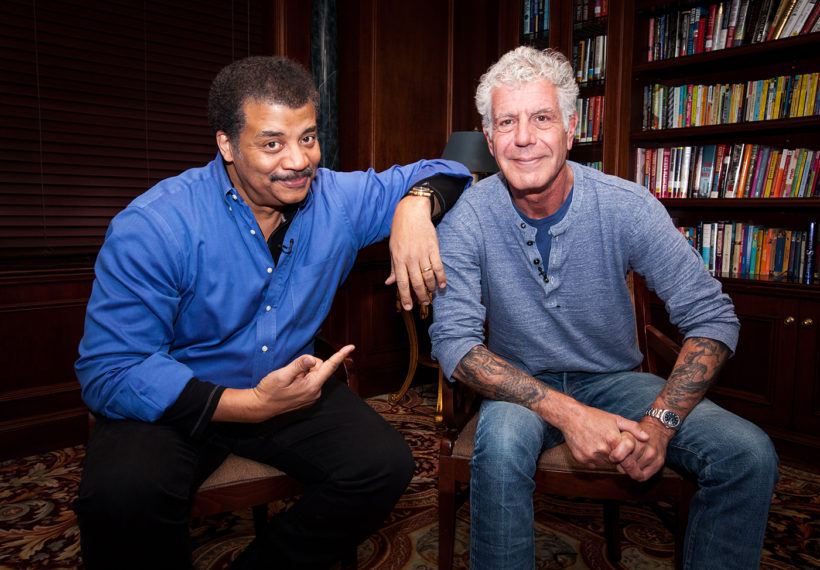

Food, science, and culture. These three words are the theme for our Season 10 premiere of StarTalk Radio. Neil deGrasse Tyson sits down with chef, author, and travel documentarian Anthony Bourdain to discuss the intersection of food, science, culture, and much, much more. Neil is joined in-studio by comic co-host Sasheer Zamata and food scientist Guy Crosby, PhD. You’ll hear about Anthony’s upbringing and how his educational experiences, like dissecting frogs, influenced his career path.

Find out more about the subjectivity of taste and why not everyone likes the same things. Get details on the genetic differences that cause people to taste things differently. Explore how the brain creates the imagery of flavor in your mind. Neil and Sasheer bond over a dislike of candy corn. You’ll learn about science’s role in the kitchen, and why most cooking is more about the decay process rather than about something being “fresh.” Discover the difference between fermentation and regular rotting. Sasheer tells us her hesitations about milk expiration dates. We investigate eating in space and why things taste different at altitude. You’ll hear about the connections between geography and spicy food. Neil shares his experience about the spiciest food he’s ever eaten, and he and Anthony ponder why some people claim there’s secretly opium in really spicy foods. StarTalk All-Stars host and “science correspondent” Natalia Reagan visits the HEATONIST shop to test some of the world’s spiciest hot sauces alongside hot sauce guru Noah Chaimberg.

Next up, we dive into molecular gastronomy. Chemical scientist and writer “SciBabe” Yvette d’Entremont stops in to help us understand some food chemistry. Guy shows us a demonstration of reverse cooking with liquid nitrogen. We answer your fan-submitted Cosmic Queries on organic foods and why natural doesn’t always mean better. Lastly, you’ll also hear about lab-grown meat and its future in society. All that, plus, Anthony talks about how his experiences in Antarctica and Beirut impacted his understanding of the world around us.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Hello, StarTalk family. The episode you're about to watch was recorded shortly before the tragic passing of celebrated writer and TV host Anthony Bourdain. We're thankful for the opportunity to share Anthony's unique perspective in the universe on food, culture...

Hello, StarTalk family.

The episode you're about to watch was recorded shortly before the tragic passing of celebrated writer and TV host Anthony Bourdain.

We're thankful for the opportunity to share Anthony's unique perspective in the universe on food, culture and life.

On behalf of all of us at StarTalk, thanks for watching.

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Welcome to the hall of the universe.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

And tonight we're discussing the science of food.

And we're featuring my interview with chef, writer and TV host Anthony Bourdain.

So let's do this.

So meet my comedic co-host for this evening, Sasheer Zamata.

Sasheer!

Excellent.

You're tweeting at the Sheer Truth.

Brilliant Twitter handle.

Love it.

And I've got with us a real live food scientist, Guy Crosby.

Guy, welcome to StarTalk.

You're also known as the cooking science guy.

You're adjunct professor of nutrition at the Harvard University School of Public Health.

Correct.

It's up in Boston, sure.

And former science editor for America's Test Kitchen.

That's right.

Very good, because we're featuring my interview with chef and renowned foodie, Anthony Bourdain.

And you know, he's host of CNN's Parts Unknown.

And what they do is they send him to all corners of the Earth, and he explores food in the context of their culture.

Brilliant concept, which he executes beautifully.

And so I wanted to know, did he have any early experiences with math or science that might sort of help to guide him or tune him on this path?

So let's check it out.

Algebra, strangely enough, was the best I ever did at any math subject.

I could somehow picture that.

But science, you know, I like dissecting frogs.

I mean, who doesn't?

Well, it served me well later as a chef.

You know where all the leg muscles are.

I do.

Little did your biology teacher know that this was for later eating.

So tell me how you came to think about food and culture.

The fact that the very phrase, it's a matter of taste, means I might like something that you don't and vice versa.

So what does it even mean for you to have a show to talk about what's good and what isn't?

Well, it is completely subjective.

I mean, they say that all food tastes are acquired or learned, that they are not, I mean, babies will eat rotten food if their mothers say this is good.

I think bitter babies, at least in this country, react to negatively.

Hence, no vegetables.

Yeah.

I never evaluate food on the show anymore.

I don't use adjectives anymore.

I never say, well, I have no toast, you know, background notes of minerality.

Does this help anyone in any way?

I say, wow, this is really good.

And they say, sure about that.

But it's entirely subjective.

I know that some people have a genetic inability to taste certain flavors or experience them differently.

I have a chef friend who did a lot of experiments with that.

One out of a small group of people will not detect certain flavors at all.

Well, if they become a colony, they could end up creating dishes that would be offensive to those who taste that, who have the capacity to taste it, and they don't, and therefore it's just fine to them.

For example, I think one of the things that's prevented the Philippines from taking their rightful place as a major world cuisine beloved by everybody on every corner, I think that's because, my guess, they like an element of bitterness.

In fact, in the Philippines, they will use bile to add that very important note to some of their traditional dishes, and that's a taste that Americans, I think, instinctively recoil from in a way that they just simply do not.

That's a treasured component.

We have textural predilections and aversions that seem innate, or at least are so deep in our culture.

America, we love anything crispy.

Anything covered in batter and crispy, we're going to love.

It's better.

We don't even need anything inside the batter.

We'll eat the batter.

But when you get into that chewy, rubbery, gelatinous, boiled chicken skin, fish skin, abalone, a lot of things that they really love, tendon in China and Japan.

Tendon.

Tendon is great.

It's fantastic.

But look at you.

I mean, that's most Americans go, oh, dude, no.

So Guy, explain to me.

Explain to me.

How is it that somebody could find something to be a delicacy and I would just find it to be nasty?

What is the science behind that other than just possibly missing the same taste, you know, not having corresponding taste buds?

Because that can't explain everything.

Right.

So what's going on there?

Well, so we can break this question down into two parts, right?

There are foods that people like and dislike, and then there are foods that just plain disgust people.

So the foods that we learn to like and dislike, that really has to do with sort of genetic inheritance.

It has to do with the maternal diet.

It has to do with, you know, what children ate as they grew up and their culture that they grew up in.

You know, like comfort foods.

People have comfort foods they like.

Is there anybody in the world who doesn't like ice cream?

Maybe one or two.

Do you like ice cream?

I don't like cold things.

What the hell?

What?

Security?

We'll get back to you in a minute.

Go.

So, what I was going to say, but now there are foods that people dislike, like oysters, right?

Oysters are because they're slimy.

Some people just don't like to eat anything that's live and kicking.

So, it reminds me of a little poem that Roy Blunt wrote.

He says, I prefer my oysters fried.

That way I know my oysters died.

That's a fast poem right there.

But then you get into foods that disgust people, right?

And that generally is out of fear.

People have fear of being harmed.

And that's what makes them so.

So, it's psychological, not scientific, not physiological.

Well, they've done animal studies where they fed animals things that make them sick.

And the animals will never eat that food again.

Whatever.

So, you know, I think the example there is like durian fruit.

If you're familiar with that, for people in Southeast Asia, they love that stuff.

It's the king of fruit.

But in the Western world, the aroma just is revolting to people.

It smells a combination of, I'll say it nicely, pig excrement mixed with turpentine and spoiling onions.

So...

Dang.

Nada, please.

Well, she'll eat it as long as it's not cold.

Heat it up, it's fine.

So what part of liking food then is not subjective?

So anything we taste, because what we taste, the receptors for our taste are built into our genes, right?

So these evolve through history as a means of survival.

So we like sweet things because it's a source of energy.

We don't like bitter things, as Anthony was saying, because a lot of toxic materials are very, very bitter.

So that's pretty objective, is that it's built into the brain.

But flavor, that's created in your mind.

So that's very, very subjective.

Wait, wait, so, Sasheer, do you think there are any foods that are just objectively gross?

Candy corn.

I don't think anyone likes candy corn.

When they put it in your trick-or-treat...

You get so upset.

It's like, this is the worst one.

Yeah, I throw it back.

I'd rather have bile.

So, Guy, you said we have...

What are the tastes that we all have?

So you get the scents from your mouth that's taste, from your nose, smell, it goes into your brain, and your brain then takes those two, puts them together, and creates the image of flavor.

We don't taste anything that's actual flavor.

Your flavor is created in your mind.

Oh, so it could be in the future when we start tickling the neurons of your brain, we can make you taste anything we want.

It's very possible, yep.

So does everyone have the same number of taste receptors?

This would be a chemical intersection of your...

Good question...

.

olfactory glands and the molecule, I presume.

Right.

No, they don't.

There's a big genetic difference.

Really?

Between, yes, what people can taste.

There are things, people we call supertasters, they are extremely sensitive to bitter.

So I bet the countries that have nasty food, they have very few taste buds.

Well, I don't know about that, but you can easily tell by just sticking your tongue out.

You can say here, this is a late night show.

And looking in the mirror.

All those bumps on your tongues, those are your taste buds.

And people that are supertasters have lots more of them.

I don't know, you may be a taster or a non-taster.

So if you have more of them, so more is better.

More is better.

More is more.

Well, not necessarily.

More is more, whether or not it's better.

Supertasters, though, are very, very picky eaters.

They don't like a lot of things.

They don't like a lot of vegetables, for example.

So they tend to have higher incidence of colon.

So now they have a physiological excuse.

Yep.

For not eating vegetables.

To reject the vegetables.

Yep, I'm afraid so.

Okay, you shouldn't do that.

It's like, oh, just my taste buds.

Physiologically, I would be there with you, but no.

So, this is fascinating because there's science infusing.

We experience at least three times a day.

So, I wanted to ask Anthony's thoughts about the role of science in the kitchen.

Is it just for the artist or is there room for the science geek such as yourself?

Let's check it out.

You know, when you scramble an egg, I forget what it's called.

The coagulation of proteins.

I'm not sure about the specific processes.

But we're all, you know, caramelization.

You know, why does your steak get brown as you cook it and develop the sugars on the outside?

All of these things are essential scientific techniques or processes.

There's a science reason.

Every cook understands instinctively.

They may not be able to name what's happening, but they understand very, very, very well when, you know, the effect you want, how to get there, when it's going wrong, when it's going right.

So even something as simple as scrabbling an egg is essentially a scientific manipulation of an ingredient.

By exposing it to both heat and movement and incorporating air, you're making it behave and egg behave in a desired way.

It reminds me, this is an obscure analogy, but it reminds me of when medicine became modern, it did so because, in part, it looked to see what sort of folk remedies existed around the world and cultures.

Oh, you chew on this bark and that gets rid of your headache.

Well, what got rid of your headache?

So you find out what's in the bark.

And there's this molecule that becomes what we today call aspirin.

And so you extract the active ingredient, and then you can exploit that to great gain.

And so it seems to me if you knew exactly the moment and why a sautéed onion becomes sweet, you can possibly hone in on that and exploit that fact with other foods.

And that's what chefs are doing, some chefs are doing every day.

I have friends who are rotting all varieties of things in some dark corner of their cellar, experimenting, talking to microbiologists from major universities, talking to them late at night, working with them in kitchens, discussing the wonders of fermentation.

What can you ferment?

What's going on in miso?

How can I apply that to something else?

So much of food is not about freshness, it's what's called that sweet spot, the precise moment in its decay where it is best.

Sushi being the best example.

Anyone who comes and tells you that, you know, oh I went to a sushi bar last night, it was the best, the fish was so fresh, have no understanding at all of sushi.

Sushi is not about freshness at all.

First of all, even the best places deliberately cure their fish by freezing it, sometimes out of necessity to kill the critters, others because it makes it better, but it's almost never about the freshest fish.

Fresh fish is right out of the water, is still in rigor, and it's often rubbery and unpleasant and without much flavor, which is why in Iceland they rot it sometimes because you get more fun.

You're looking for the perfect point in the decay of the fish.

Same with meat.

Almost everything we eat in like cheese, meat, fish, they're all aged, just wine.

So it's really about decay and rot, cheerful as that sounds.

I never knew.

Thank you.

So Guy, scientifically, what's going on when food decays?

Just straighten us out about that.

And simultaneously tell us why, for some mysterious reason, that tastes better.

All right.

Well, what happens is the animal's natural enzymes actually break down the proteins.

And what that's doing is that's creating a lot of things called peptides and amino acids that are loaded with umami flavor.

So not only does it make it more tender, but it actually adds a lot of this umami flavor to things like aged beef or anchovies or these things that have gone through that kind of aged processing.

And cheese as well.

Cheese as well, yes.

So is this just trial and error where you do it until you do it a little too much then you die and a little not enough that doesn't taste good?

So how do you guarantee hitting that sweet spot or is it just trial and error?

Hopefully it's more than better than trial and error.

That's where I think science does come into it.

That maybe the way you design your experiments where you don't go beyond the sweet spot and end up dying.

You need to set it up and be able to tell when things are just about right and that's how you design the experiments to give you that information.

That's where science helps.

You're bad at what?

Figuring out when things are not bad anymore.

Or when things have gone past the sweet spot.

So do you like stinky cheese?

I mean I'm bad at smelling generally.

Are you the first to smell?

Well let me smell that milk to see if it's bad.

I smell the milk and I'll be like, it's probably fine.

And then it's not.

Okay so you're very sensitive to it then.

No, no, I mean you smell milk and you say it might be bad, but then you drink it and it's okay.

Well I guess I'm just like the expiration date's made up.

It's probably fine.

They're trying to get more of my money.

So I'm going to drink this milk until I'm done with it.

I'm not testing that hypothesis.

Let me presume they're all lying to me and let my milk go past its expiration date.

I'm a busy woman.

I just haven't gotten around to drinking a full gallon of milk yet.

So what's the difference between fermentation, which we all know and love, that's responsible for most of the alcohol we drink, and something just rotting?

Yeah, okay.

Or is it the same thing?

Well in some ways it is similar.

Though fermentation is created by bacteria called lactobacillus bacteria that form lactic acid.

It lowers the pH and that stops all other bacteria, especially the harmful ones that might spoil the food and make you sick from growing.

So the good bacteria wins out over the bad bacteria?

Yeah, and lactobacillus bacteria don't make us sick, alright?

But the bad ones are...

Oh, so you can err on the too much side, and you might not like it, but it's not going to kill you.

Correct.

So I wanted to ask Anthony about food in space.

And you know he's thought about this, because he thinks about food everywhere, including space, so let's check it out.

I did an episode of Top Chef at NASA headquarters, and we were talking about food in space.

And of course, your entire taste perception, I was talking to Chuck Yeager.

The Chuck Yeager.

Yes.

And talking about what you crave, when you've been away from your favorite restaurants, or any restaurants for a considerable amount of time.

And he talked about how your ability to perceive flavors changes at altitude.

People experience this in planes, of course.

Plane food is altered so that it makes up for the effects of altitude.

But astronauts get it really bad, and the stuff they crave more than anything, so Mr.

Yeager told me, is hot sauce.

Like, you know, Tabasco or anything spicy, because up there everything tastes bland.

So you're telling me those bulky areas in their spacesuits, they're smuggling bottles of hot sauce on the way up.

The astronauts I've spoken to, they say this without hesitation, that they eagerly want spicy foods, and they find themselves visiting other national modules of the space station where their food tends to be spicy rather than their American food.

Yeah, so that would be tough for me, bland food for nine months.

I went, I trained in Jiu Jitsu, and I foolishly decided I was going to compete a few times.

And in the run up to the competition, I had to cut weight to make my weight category, which meant doing without salt at all for a week.

So you don't retain the water, yeah.

It's horrible, it is horrible.

No matter how much I eat, I mean, I boil a whole chicken loaded with herb and pepper and everything I could, but never satisfied.

And I would just get crazier and crazier from the lack of salt to the point that I found myself sitting on the subway in the summer looking at a particularly sweaty homeless dude and thinking, oh, I'd like to lick his neck.

Just one lick.

That is fascinatingly gross.

So physiologically, the body knows what it needs.

Is that what this comes down to?

It does, yes, in this case.

He needs it that badly.

Well, salt has a very, very important role among other things, but one of the most important things is it maintains the fluid level in the body.

Which he's trying to disrupt on purpose.

If you went the other way and had too much salt, you have too much fluid, and that's when you get high blood pressure.

But if you have almost no salt and no fluid, you have a real strong craving because you want to reestablish that balance of getting just the right amount of salt.

Enough to lick the neck of a homeless person in the street.

Well, I'm not sure he'd go that far, but it shows you what an extreme case...

He had the thought.

Yes, he did.

So the body's trying to take care of itself.

Yes, it is.

In spite of whatever your stupid-ass behavior might be doing with it.

Yes.

Yes, okay.

Just getting your buy-in on that.

Well, up next, we'll feel the burn as we explore the science of spicy food when Star Talk returns.

We're featuring my interview with celebrity foodie Anthony Bourdain.

His food and travel show, Parts Unknown, has taken him on culinary adventures across the globe.

And I asked him about the connection between geography and spicy food.

Check it out.

Why do some regions of the world eat spicy foods and others not?

And why does it seem that spicy foods corresponds with latitude on earth?

The farther away from the equator you get, the less spicy the food becomes.

Places where food used to rot, people would use spice to cover up the funk of food that was not meat, protein, fish, that was not particularly fresh, and also spices preserve food.

I think when you look at the spicy food belt, you see people who had to.

I mean, this is the story of food.

It explains a lot about if you're in a country where there's a lot of dried legumes.

Often, it was a siege culture, people who had to wall themselves up, surrounded by enemies and wait for the enemies to die of starvation because they had plenty of lentils.

That's an oversimplification, but true.

Why do people eat really rotten food sometimes?

Why do they like Harkhal, a rotten shark in Iceland, which is literally rotted to the point of putrification?

Their flavor spectrum up there was very narrow.

I think the pallets got bored.

They didn't have access to much in the way of spices, so they just started rotting stuff.

But I think the spice question is simple.

No refrigeration and hot temperatures.

So, Guy, how does spice preserve food?

What's going on?

Well, so all these foods start to rot because one reason, the bacteria start to attack them and eat up the proteins and make all these smelly things.

But spices are really, really good.

Some of them, about a dozen really good antibacterial agents.

Things like oregano and thyme, they have really strong activity against bacteria, so they will kill off and preserve the food for a longer period of time.

Plus, they will mask any sort of off flavors that might develop in the meantime.

My favorite spice is scary spice.

Then baby, posh, ginger, sporty.

I forgot all about them.

How could you forget?

Oh, man.

I was like, wait, how old are you?

So, Anthony Bourdain, he's tried every spicy food on earth.

And then I told him about the spiciest food that I ever experienced.

Let's check it out.

I ate at an authentic Szechuan restaurant in San Francisco recently.

And I was waiting for the next dish to be some reprieve from the previous dish.

And that did not happen.

Every single dish was hotter than the previous one.

Even in Chengdu, the major city in Szechuan province, where I've been a few times, you'll see locals at their favorite Szechuan hot pot place literally doubled over holding their stomachs, mopping their necks, faces beat red.

It can be excruciatingly painful.

And this is an interesting scientific phenomenon that's always intrigued me.

A lot of people suggest that their favorite Szechuan hot pot has, that they secretly lace it with opium.

Because what happens is they eat this scorchingly hot food, very uncomfortable to eat, but intensely pleasurable.

And the next day they wake up with a craving.

And I find this as well when I'm eating really, really, really spicy food.

And some have suggested that this is due to there's this flood of endorphins that your brain releases when experiencing really painful, painfully hot food.

And that, I guess that happens while you're eating it.

And the next morning it's not there.

And you feel this sudden withdrawal.

You feel the absence of that endorphin rush that you had the night before.

And this immediately compels you to get more.

I've had this experience after tattoos as well.

I've had a lot of people who've gotten tattooed and like me say that right afterwards they always want another, which seems counterintuitive.

This is good because I don't have any.

So maybe if I should stay that way.

So this interesting, this sort of endorphin rush from spicy food.

So, you know, we sent out Natalia Reagan, one of our Star Talk science correspondents.

So let's see what she got for us.

Hey, Neil, I'm with hot sauce guru, Noah Chaimberg, here at The Heatin'ist.

It is a hot sauce shop here in Brooklyn, and we are going to try some of the hottest hot sauces out there in the world, and hopefully understand why people like the pleasure of painfully spicy food.

What do you have for me, Noah?

So we're going to start off with a Bajan style sauce here, and in Barbados, they always put mustard in the hot sauce.

Oh, I like that.

It's nice, got a little sweetness to it.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Nice kick, too.

It does.

And the interesting thing, the reason why we feel the spice is that chili peppers have capsaicin, which is a compound that actually was produced by plants to keep mammals from eating them, because mammals actually grind the seeds, and so it's not great for dispersing chili peppers.

But birds swallow the seeds, and they are great at dispersing seeds because they can fly and they can eliminate them wherever they may go.

So next up we have, from a small farm in Japan, this sauce is made with golden habaneros and a bit of dried mango.

The sweet and the nice kick in the butt right afterwards.

I'm going to need some milk.

And the reason why I take a sip of milk is actually the fat and the casein in the milk binds the capsaicin and washes it away, which is exactly what I need right now.

The other thing that works well is alcohol, but it can't be something weak.

It has to be strong alcohol.

So no beer.

You got to have a shot of something.

Oh, good.

So the last sauce for today.

That is very red.

It is.

This sauce is made with Carolina Reaper, which since 2013 has been in the Guinness Book of Records as the world's hottest pepper.

Okay, why just since 2000?

Like what was it before 2013?

It actually didn't exist before then.

So the Carolina Reaper is a hybrid pepper.

Here we go.

It's nice knowing you, Neil.

Yeah, so people are always looking for something hotter and hotter because of that pleasure that we get from the pain of hot sauce.

Oh, God.

Son of a motherless goat, that's hot.

There you have it, Neil.

This awful searing, life-altering pain I'm feeling is a result of hybridization, methodically cross-breeding two types of peppers for this ultimate pain.

Thanks, science.

What next?

We'll be taking your questions on the science of food when Star Talk returns.

Welcome back to Star Talk from the American Museum of Natural History.

We're featuring my interview with chef, author, world traveler, Anthony Bourdain.

And we're talking about the science of food.

Check it out.

There's a branch of the culinary universe that seems to focus on molecular.

Molecular gastronomy, yes.

Am I correct in characterizing that as how can I bring as much science as I possibly can to the protein molecules and the freezing and the cooking times?

Does this subtract the experience from you or add to it?

It depends.

I know a few chefs who are really, really great at this and they're like scientists.

I was just talking to Wiley DeFrain, one of the real masters of this area of cooking.

And he says, look, in my restaurant, we ask questions.

We're asking questions about food and the dining experience.

They're not necessarily looking to dazzle or to challenge their diners.

They're asking questions like, can I deep fry mayonnaise?

Answer, yes.

Also, I'm sorry, I would have never in my whole life, that is a not that I'm sorry, I would never thought that.

But once he figured out how to deep fry mayonnaise, he figured out how he could fry other sauces, how to cause them to stay essentially solid.

Solid and not explode when you throw it to hot fat.

Ferran Adria, Wiley-Dufresne and a very few other chefs make this experience intensely pleasurable and exciting and fun, many other imitators.

It is a long painful slog through one of their meals where it's a science class for its own sake.

You know, look, I can, look, look what I can do.

We're joining us now for a conversation on the intersection of food and science is chemical scientist Yvette D'Entremont.

And you're known simply as SciBabe.

SciBabe, indeed.

And so you got a reputation on line for doing what?

Debunking bad science with a combination of good science and dick jokes.

But as it relates to food.

Yes, yes, a lot of, a lot of people got it.

Because it's bad science, but it's especially bad science related to food.

Oh my God, yes.

So do chefs, do you think they would make better food if they had a firm understanding of the chemistry of food?

I think it can help, but I've seen somebody try to make mashed potatoes using amylase to break down, they're like, look, I can make the creamiest mashed potatoes you've ever made, you've ever seen.

Instead, they made sugary goop because when you break down starch, you get sugar.

Sometimes you just have to add some butter and cream to your potatoes.

Well, so Guy, you have some science food demo you can share with us.

Yeah, we do.

I just happened to have some liquid nitrogen, right?

Never leave home without it.

Yes.

And of course you need some goggles.

Yes, for sure.

You're the only one with goggles?

We don't get goggles?

Yeah, we're going to do some reverse cooking, huh?

What do you have for us?

Well, I happen to have right here some ice cream mix, too.

Oh, that's ice cream mix.

It looks like blueberry ice cream.

So we're going to drop some in.

This is like casting a spell.

Would these be StarTalk dogs?

And look at them, they're forming.

So why don't you have a chant?

Toilet in trouble, toilet in trouble.

Go ahead, you're doing a great job.

Have you ever heard of the vegetarian witches?

No.

Eye of potato, head of lettuce.

I think we've probably got enough in here, huh?

Let's see what we've got.

Let's put in a little.

I'm just curious.

Ooh, that's nice and cold.

Yeah, isn't it though?

Now, do you do this at home?

Every day.

And the whole point of this liquid nitrogen is it freezes the thing so fast that the crystals are extremely small, so they have a really super smooth texture.

So you get only big crystals when it freezes slowly?

Slowly, yeah.

And that makes it very grainy, so you don't want that.

There's still smoke coming off of it.

Yeah, it may be very cold, so be careful.

Well, our Star Talk fans had their own questions about the science of food, which means right now it's time for Cosmic Queries.

And so we took your questions of trying to separate food myth from food science.

So bring it on, Sasheer.

Okay, Drew G from Instagram says, is there definitive evidence that certified organic foods are actually healthier?

At this point in time, there is no evidence to suggest that organic foods are healthier than conventionally grown produce.

And the other thing is organic uses pesticides too.

A lot of people think they're pesticide free.

Notice it doesn't say pesticide free on the label.

It says organic.

So they're just different farming techniques.

But you're a scientist.

What do you know?

Guy, you want to add to that?

Yes, there is generally though, you'll find the one area that it does show some improvement in organic is the chemical pesticide residues because they don't allow real chemical ones in organic.

So you mean artificial chemicals as opposed to natural chemicals?

Actually, there are some synthetic pesticides allowed in organic farming.

And not all synthetics are necessarily more toxic than the naturally occurring ones.

There are a lot of crossover between what's more toxic, what's less toxic, and natural doesn't mean better for you.

I've heard a rumor that polio is natural.

I'm just saying, natural does not mean good for you.

Up next, Anthony Bourdain describes his culinary adventures in Antarctica when Star Talk returns.

We're featuring my interview with food and travel show host, Anthony Bourdain.

And he recently visited an unlikely spot for food lovers, Antarctica.

And I asked him about that experience.

Check it out.

It's another planet.

It feels like another planet.

On one hand, everyone should go and see it.

On the other hand, it kind of defeats a purpose.

It is the last un-effed-up place on Earth.

It's pristine.

Every drop of urine goes into bottles, then into 55-gallon drums and shipped back to America, along with, or elsewhere, with every little bit of waste.

It is the most incredible spot, place of pure science and pure learning, where people are incrementally seeking answers to questions they might never answer in their life.

They're just looking to move things forward.

So we met with the guys with a super telescope, part of an array, I guess, that goes around the entire globe.

It's looking at the sun, some people collecting neutrinos, which I don't really fully underst-

no, I don't understand at all, but they sound really cool.

So what do they eat?

Do they got to ship in the steaks and the vegetables?

Well, everything comes in mostly by ship, but some stuff by plane.

Everything is essentially processed, frozen.

Frozen, really.

And one of the refrains when you arrive from the people who spent months there is do you have any freshies?

It's like The Living Dead, do you have brains?

They're like, do you have any freshies?

So, there's a real premium on the rare arrival of lettuce or avocados or anything fresh, but they do a lot with a little.

And so, was that your first sort of baptism into a community of scientists?

Yes, for sure.

I found it interesting when going out to visit the penguin colonies though, we were on a helicopter out to the site and a bunch of fresh-faced, very enthusiastic kids who'd come down to help out an intern, I guess, would go out and hug the penguin day.

They were all excited that they'd go out and get to tag penguins and hold one.

Penguins are cute.

In all the movies.

Yeah.

Well, they didn't tell them that when you pick up a penguin, they spray you with a horrifying array of wet diarrhea.

They all came back rather downcast looking and smelling a bit ripe.

So, Guy, he says Antarctica is like another planet.

Of course, he's right.

It's the closest thing on Earth we have to Mars where it's cold and dry.

And how would your cooking advice differ for people living on another planet?

Well, it's kind of like being in an airplane in a way, right?

It's cold, it's dry, and you've got maybe different pressure, different atmosphere.

So probably the food's going to be bland there unless they really spice it up, add a lot of seasoning to it.

Right.

So this experience he had in Antarctica gave him a unique perspective on climate change.

Let's check it out.

The climate change discussion is no more acutely felt, at least in people's minds or observed in Antarctica where they're really looking at it and talk about it a lot.

But of course it's perilous now to talk about it because everyone is fully aware that their data is being deleted from government computers, that if they find themselves on a blacklist of people who might possibly be interested in the subject that they could find themselves suddenly not needed.

These are not good times for science or scientists and they felt very much under threat down there and for good reason.

Particularly when you're pursuing subjects that aren't going to have a useful monetary application anytime soon, tough argument to make in this political climate.

But I see it everywhere.

The fishing industry is everywhere affected.

The Caribbean where I've seen in my own lifetime not just whole reefs, all the reefs bleached and lifeless now.

I'm seeing the physical changes, but the people who really seem to feel it most and notice it are farmers, fishermen, they're feeling it.

This would affect cuisine directly?

Yeah.

There's no doubt about it.

Some species are thriving, others disappearing.

That changes what we eat.

Chefs and cooks and anybody who needs to feed their family responds to what's available.

That's always been the engine of cooking.

Yvette, you worked as a chemist in the agricultural industry.

Describe to me your first-hand experience between food and environment.

I worked researching pesticides to make sure that they were safe for crop application and of course for humans.

This also gave me a really good perspective on how deeply connected what we do with agriculture is to the environment.

Because every time that you use more land to grow crops, you're using less land for wildlife.

So we need to, we're seeing technologies being deployed to try to fight this more and more as we move forward.

So Guy, what's the first consequence in the chef's kitchen?

Well, of course, you're going to have higher CO2 and temperatures.

So that's going to change your seasonal availability.

Of course, costs will go up and nutritional quality tends to go down.

So, yeah, so those would be some of the issues.

But on the other hand, you do have some advantages, for example, some places will improve.

Some things will like, for example, you know, grapes really like the heat stress to create really good wine.

So you might even find that wine even in England might actually become pretty good.

Did you just have, did you, you put the word wine and England in the same sentence?

I did, yes.

So what you're saying is all the other food stuffs will be crap, but we'll have really good wine.

Well, coming up in the science of food, Anthony Bourdain and I discuss meat grown in the laboratory when Star Talk returns.

We're talking about the science of food and the culture of food.

And I asked food and travel host Anthony Bourdain what he's learned from sharing meals at so many different tables around the world.

Check it out.

I guess it became fairly quickly apparent that food was intensely personal, that it was a reflection of a place, of a culture, of a history, often a very painful history.

Maybe the most important example in the trajectory of my show was Beirut in 2006.

When we were doing what was ostensibly still a food and travel show, we'd finished shooting.

Very travelogue.

Yeah, we'd finished shooting another sort of upbeat, snarky maybe restaurant scene and the crew joined me in my room for beers in the mini bar and we're looking lazily out the window and rockets and gunships attacked the airport, blowing it to smithereens.

Our local crew disappears for the border and we found ourselves in a war, blockaded, unable to leave and trapped in Beirut for the next week or so waiting to be evacuated.

By the US military?

Yeah, the Navy and Marines took us off the beach in LCUs.

Dramatic.

In an LCU filled with wailing, crying refugees and just looking out at the water as we pulled away from the beach.

It just struck me as obscene to contemplate ever doing an upbeat food show in a world that allows things like this to happen regularly.

So this was a pivot point?

Absolutely.

Everything changed at that moment.

And I started looking around.

And I was determined, you know, if I'm sitting in the hills of Laos, I'm going to ask the obvious question when my host is missing a limb.

Where'd you lose a limb?

And we're eating, true, but chances are he's going to tell me well, I wasn't alive for the secret war here, but your military was kind enough to leave behind, you know, a few million tons of unexploded ordnance that I happened to step on one of those.

I think people open up to me and tell me about their lives because I'm asking simple questions.

We're just eating.

So, Cecilia, why do you think sharing a meal seems to open people up culturally?

I think food does have kind of an emotional tie.

You're already like in a vulnerable state because you're hungry, so you're fulfilling something.

And it's just nice to be in a communal space where you're sharing this moment together or eating good food together.

I mean, hopefully good food and enjoying something.

So it's, you know, you're prone to talking and you can actually be able to share more information that way than just like, I don't know, setting up a meeting or something.

Let's take a meeting.

Right, it's very different over food, isn't it?

Exactly.

So Yvette, you keep up with sort of techie trends in food.

So what about lab-grown meat?

What is the potential for that?

There is a large impact on the environment from this sector of agriculture.

And if this can reduce our impact on the environment, while still giving me something yummy, shove it in my face hole, okay?

But Guy, is this, how realistic is lab-grown meat as a replacement for somebody's ribeye?

Well, there's a lot of new companies working feverishly right now to try to get this done through cell culture.

And it's estimated, you know, the typical processed type of meat, you know, like ground hamburger or a sausage, maybe five years away before it's actually on the market.

Because that one texture is not so much the issue.

It's already ground up.

Yeah, it's not a structured meat like a whole big steak or something.

Right.

Which would be maybe ten years away before they're able to bring that up.

Well, I asked chef and author Anthony Bourdain what he thinks about lab-grown meat.

Let's check it out.

I think laboratory-grown meat, the thought horrifies me as a chef.

Really?

As a cook, as a sort of passionate.

You still get to cook it.

You just don't have to kill the animal.

Yeah, but I mean, we're talking meat-like, aren't we?

I mean, so much of meat is textural.

It is the interconnected viscera and muscle and fat.

What makes meat interesting is the degree of exercise, its diet.

What you prize in beef is the marbling, the ripple of fat through lean that comes from movement.

Presumably, your laboratory-grown meat will not have moved at any point.

But I suspect…

It's out at Pasteur now.

It's that cube.

Given the way the world is going, we might well have to eat laboratory-grown meat soon, if not our neighbors.

I think the first round of it will be ground meat.

Might replace hamburger meat, which you're not in search of the marbling and the textures and the…

Well, not as much as the T-bone or the rib eye.

Well, not as much.

Right, right.

That's all I'm saying.

That might be its first foray.

But that could completely transform your world.

Yes, and look, a lot of the world…

Not only your world, the world.

Look, there are a lot of hungry people in this world for whom a single chicken is a life or death thing.

They need protein and I guess laboratory-grown meat would be a solution.

But we've given up on something really fundamental.

When we move to laboratory-grown meat, when any culture does, it's a surrender.

We're shutting ourselves off to something that goes back to the beginning of human civilization.

In fact, it's likely it was the beginning of human civilization, the fire and a hunk of meat.

You know, it was the first time people probably cooperated, you know, I'll kill the animal.

You drag it back to the fire, you build the fire, and then we're all sitting around figuring out how we're going to divide up this thing.

That's kind of the beginning of any kind of organized society, according to some scientists.

The idea that food goes back, capturing the culture of a place, capturing a time, I respect that.

However, just because something happened long ago, and you respect it because it's old, doesn't mean something can't happen that's new, and then you respect it because it's new.

You can create something new that a thousand years, they'll look back and say, way back in the early 21st century, this new product emerged.

It is cultural.

It's traceable that far back.

And it emerged at a time when there were food shortages, when not all the world had access to proteins, not all the world had access to vitamin enrichment.

People were dying, climates were changing.

It may be that we're living at the cusp of a food revolution, where we no longer look towards the cultures disparate around the world that produce one kind of food or another.

Maybe the very culture we're after is the culture of the Petri dish.

Maybe that's the culture.

We should ask, how should we manage our food?

What should we do about the shortages today, especially in a growing population?

So I see the future of food as we're going to look back, we're going to look back to the early 21st century.

We're going to say, wow, we invented whole new cuisines that could feed the world.

That is a cosmic perspective.

I've been your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

As always, I bid you to keep looking up.

See you next time.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron