It’s claustrophobic, dangerous, and there were still doubts that the mission was going to succeed. But as legendary Apollo Flight Director Gene Kranz says, “Failure is not an option.” On this episode of StarTalk Radio, Neil deGrasse Tyson, comic co-host Chuck Nice and Astro Mike Massimino, two-time space shuttle veteran and Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Columbia University, sit down together to celebrate the life and legacy of Neil Armstrong in conjunction with the release of the brand-new film First Man.

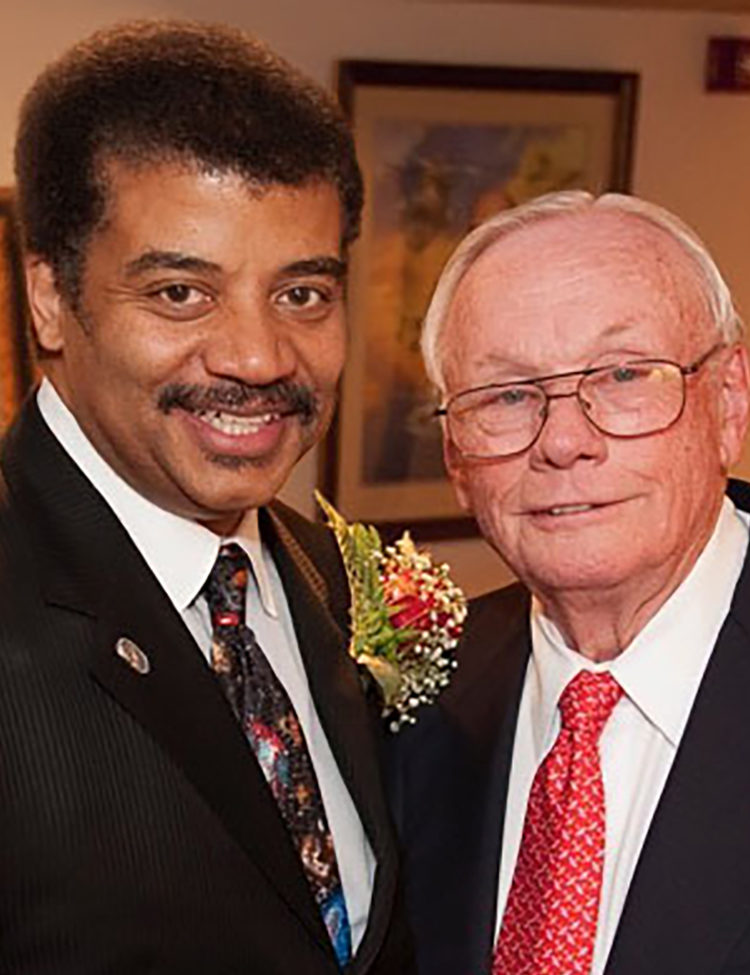

The film follows Neil (portrayed by Ryan Gosling) and his career leading up to the Moon landing. Whether he’s pushing altitude limits in an X-15, testing docking mechanics in a Gemini capsule above the Earth, or landing on the Moon with only drops of fuel remaining – he’s as cool as ice. Neil and Mike discuss the film and whether or not it accurately portrays Armstrong as he was in real life. You’ll hear from Armstrong himself as Neil caught up with the real-life first man on the Moon at the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission Tyson hosted in 2009 at The National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. You’ll also hear from Gene Kranz, who was also at the event, who tells Neil what it was like to be a part of the mission from the ground.

Explore why, even though Armstrong was quiet and weary of the spotlight, everyone agreed he was the right man for the job. Mike shares his experience meeting Armstrong while he was an astronaut in training. Neil also describes the first time he met Armstrong – on a cruise to Mauritania to view a solar eclipse, for which the 14-year-old Tyson had won a scholarship through the Explorers Club. Mike explains how Armstrong’s first words on the Moon influenced him when he sent the first tweet ever tweeted from space.

You’ll hear why the Moon landing was so stressful for everyone on the ground, and Mike explains the honesty that comes with discussing the chances of having unsuccessful missions. You’ll also learn more about the Omega watches that were used on Apollo 11 and how NASA decided which watch brand to choose. All that, plus, Neil reflects upon the Apollo 11 mission and how it was perceived not as an American event, but a world event, inspiring millions and millions of people across the globe.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. This is StarTalk, and I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist. And today, this is a StarTalk devoted to the...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk, and I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

And today, this is a StarTalk devoted to the first man.

Adam?

That was Chuck Nice, my co-host of the first man special edition of StarTalk.

We're, of course, talking about Neil Armstrong and his first steps on the moon.

And we're not going to do that unless we bring in an astronaut.

Wow.

I mean, isn't it cool?

I got on my Rolodex, I got some astronauts.

Wow.

And one of my favorites, actually, he is my favorite, but I don't want to tell him.

That's nice.

Mike Massimino, Mike, dude, thanks for coming.

Chuck, thanks for having me.

I'm so glad I could join you today.

This is on short notice.

We saw each other just the other night.

Both, we saw a preview screening of the film First Man, all about Neil Armstrong.

And I realize it's not about Neil Armstrong.

It is Neil Armstrong's view.

Yeah.

Right?

It's his point of view of the whole.

Yeah.

Who he was.

They captured his personality, what he was about, the way he approached his work.

Yeah.

It was, I thought it was fantastic.

Well, let me finish introducing you.

So you're a former NASA astronaut.

Yes.

You're a mechanical engineer.

You're a professor at Columbia University.

And you're a senior space advisor to the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum.

Thank you for mentioning all those things.

Yeah.

Oh, it's good to see you guys, especially to talk about my boyhood hero, Neil Armstrong.

So did you guys know Neil Armstrong?

Can I finish introducing this thing?

Oh, you're still on this introduction?

Sorry.

Holy moly.

You're a veteran of two space flights.

STS, which is NASA code for Space Transportation System.

Correct.

Oh, cool.

It actually makes sense.

Does it?

I thought it was called a shuttle.

Shuttle.

Shuttle mission 109 in 2002 and 125, that was a good one, in May 2009, the last servicing mission of the Hubble Telescope, giving it life into the 2010s.

And you had four spacewalks.

And you're the...

Okay, he's the first man unto himself.

Yes, he is.

The first man to...

Tweet from space.

Take that, Neil Armstrong.

Okay, so Neil Armstrong said, one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

What were your first tweets from space?

Yeah, that's the problem.

Now, there's a Neil Armstrong story here related to it.

Okay, go, go, go.

The very first time, Neil Armstrong came to speak to my astronaut class.

We were there for a total of four days.

So, you're still like an astronaut cadet or something.

Yeah, we were just getting like, he was there for us.

He happened to be in town for his physical.

Our training manager reached out to him.

In Houston.

Right, at the Johnson Space Center.

All new astronauts.

And she asked him, Paige Molesby was her name.

She went and gave a message over to the clinic, would he come speak to us?

And he said he would, but he only wanted to speak to the new astronauts.

So, he came over and talked to us mainly about flying in the X-15 and we asked him questions.

The X-15, the test plane from NASA, based on a military, I mean, it's a...

It's a rocket plane.

A supersonic rocket plane.

Yeah, and it was one of the more, I don't know, maybe the most successful experimental aircraft ever built.

They went like Mach 7, a couple of those guys...

Seven times the speed of sound.

Yeah, and a couple of those guys earned their astronaut wings.

For having done so.

For altitude, yeah, that's how high this airplane could go.

It could get you to what, you know, space is an arbitrary boundary.

That's another story.

But they were able to earn astronaut wings in that aircraft.

Earth itself is in space.

Yes, it is.

Have you ever been to space?

That's another story.

I hate to bring this up because then we'll have a whole other show going on about the boundary of space.

But an amazing aircraft.

He talked about that in other things and we got to meet him and talk to him.

But the day after we were at a...

It was like a luncheon going on because there was a reunion as well as him coming in for his physical.

And I ended up next to him on the food line, you know, making a sandwich.

Damn, even the luncheon had to go on the chow line.

Wow.

That's cold.

That doesn't even seem right.

That's wrong.

It wasn't bad food though.

Even though it was government food.

Anyway, so he's next to me.

I said to myself, Neil, I had to say something to this guy.

Because I'm next to him.

I don't know how it happened, but serendipitously.

And I asked him, when did you think of that first thing that you said on the moon?

The one small step for man.

I go, did your wife tell you?

Did you get a publicist?

How did you come up with this?

And he turned to me and said, well Mike, I thought about it only after we landed.

Because if we didn't land, I wouldn't have to say anything.

It wouldn't make a difference.

And so I concentrated only on the landing.

Saves his brain energy.

But I think the message he was trying to get to me as a new astronaut, or I don't know if he was trying, but the message I took was, you take care of business first and you worry about other stuff later.

So his focus was landing on the moon.

So for my tweet, I did the same approach.

I said, I'm not going to worry about this first tweet.

We have to launch into space.

We have to get there alive and successfully.

I got a job to do.

Big mistake is right.

This sounds like a mistake story.

So I get there and it's, all right, we're alive and it's time, the computers are up and running on day one.

And so I need to come up with something.

So what I tweeted was, launch was awesome.

The adventure of a lifetime has begun.

I'm feeling great, enjoying the view.

Something like that.

But the first, it was okay, but during the mission, I was paying attention to the mission, of course.

During the mission, aside from sidebars, I didn't get any email from my kids.

My kids were, they were both teenagers.

I love my kids.

They were both in high school.

But they were very happy that I was away from the planet at that time and they were ignoring me.

And I'm writing them, you know, nothing.

They could have taken it personally.

Some dads go on a business trip.

You left planet Earth.

They were happy I was away.

And they were like, Dad, annoying Dad can't bother us anymore.

And I wasn't getting an email from him.

Was Dad in New York or was he in space?

Well, they knew I wasn't there and they were just happy enough they didn't want to be reminded.

So I wasn't getting an email from them.

Saturday comes, Saturday comes and Saturday Night Live makes fun of this tweet, Neil.

And this was in 09, so it's the 40th anniversary of the, almost the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11.

And Seth Meyers on SNL says, we have the first tweet from space, Mike Massimino.

And here it is.

Launch was awesome.

In 40 years, we've gone from one giant leap for mankind to launch was awesome.

If we ever find life in the universe, I assume this is how we'll be notified.

And it shows my little Twitter thing and it says, geez dudes, aliens.

So they made fun of me and my kids finally sent my email on that Monday.

They sent me email on that Monday and I was, after the spacewalks were over, like dad, thanks for saving the Hubble.

You did great.

No, it was dad.

They made fun of you on Saturday Night Live.

All the kids at school loved it.

Keep saying stupid stuff.

So I don't think Neil Armstrong ever got a reaction like that from his kids on that.

So that was a first tweet.

So that was bad advice for you.

No, it was still good advice.

I still think it's good advice because his advice was you take care of business first and that's what you concentrate on and I think that's the way he was.

And I think that's why he was chosen to be the first man.

If only he had followed it up with and make sure you schedule your tweets.

And also this story and others we can find in your book, Spaceman.

Yes.

Spaceman.

Thank you.

Thanks for that plug.

That's a plug.

Yes, it is a plug.

It's authentically conceived.

You're a great storyteller and I love the book.

Thank you.

And you didn't fix the cover photo though because you're sitting there smiling.

Oh, yeah, I know.

And there's a rocket coming out of your ear that's launched behind you.

Well, I was told the publisher is in charge of the...

You can have input for the cover, but they...

I was in charge of the words inside.

It looked like you had earwax with a plane coming out of it.

In fact, if you see the...

I've heard other comments which we can't mention about what that looks like.

So, yes, I agree.

So, the two of us saw a pre-screening of First Man.

And everything I know about Neil Armstrong, because I knew him...

I mean, I don't claim I knew him well.

We weren't beer-drinking buddies.

But, I mean, we were acquaintances, I should say.

And everything I knew about him, and I think is true for you, all you knew about him, all that you knew of him, was consistent with how he was portrayed in this film.

Would you agree?

Absolutely, yeah.

Everything that I knew about him...

So, give me your best characterization of him, because some people don't even know that.

I would say that he loved flying airplanes, he loved doing his job, he loved being a test pilot.

He was a fighter pilot in Korea, then a test pilot.

He was, I guess, a very thoughtful engineer, but loved flying.

When he came and spoke to our astronaut class...

Oh, he's got that engineer club he's in.

But he saw it as an engineering problem, as a challenge, and that's why I think he was not just a great pilot, because he loved flying, but also a great test pilot, because he enjoyed the engineering behind it.

And that was pretty impressive, I thought.

I had never thought about that.

You could be Flyboy and say, give me that machine.

If you're an engineer, you're thinking about the machine.

And if the aerodynamics...

If you're really into that, like he was, I think it was...

And not all great engineers, I think, can make great pilots, but he was one of those that could, and I think that's why you have a really special test pilot.

And do they ever make a change to the plane?

And he says, no, that ain't going to work.

I'm sure he chimed in.

I would expect that those conversations were made, especially back in those days, when they were doing things that were much different than what they had ever done before, and how fast they were going, how high they were going, what they were trying to achieve.

When his test pilot days, I'm sure there was a lot of those conversations.

So, I would add to that, that Neil Armstrong was not gregarious.

He was a very quiet man, did not seek publicity, did not, you know, he's not the person who you'd say is the life of the party.

But sometimes the people who are not the life of the party are sitting there doing nothing.

He's sitting there in his head, figuring stuff out.

It's the active, restless brain of the engineer.

And so, this was surely captured.

That was him.

And when I first met him, Neil, you described that really well.

When he got up there in front of our...

We all stood up and gave him a standing ovation.

And just about all...

I was one of the younger people in that group of new astronauts in 96.

So, just about everyone in that room, maybe one or two, wouldn't remember, remembered where they were.

And he and that episode of what he did landing on the moon, that whole mission, inspired most of us to become astronauts, I would say.

We all remembered it.

So, you're meeting your hero.

We're meeting our hero.

And it was just me, it was everybody.

And he was, he's the man, right?

He was, he was the man.

And he gets up there and was, it seemed almost like he was painfully shy.

Almost that it was hard for him to talk.

And he, he didn't mention the moon at all.

He talked about test flying and how important that is and how you have to be diligent about it and how much he loved doing that.

And after he was done, when we got the questions and answers, then we started asking what was it like on the moon.

But up to that point, he was delivering that message.

Almost painfully shy, but he was so, he loved so, so much what he did and he felt it was so important that that's what he focused on.

He was the right man for the job.

Do you think NASA chose him to be the first on the moon because of all of this?

Because he does not seek publicity?

Because if they got some grand stand in, yo, look at me, I'm on the moon.

Here's my book about me being on the moon.

Here's my talk show interview.

I've got a need for speed.

You mean like if it was one of us.

Do you think they thought that through?

I think that...

They needed someone humble.

That seems like...

I used to think that maybe at first, but I think lately in the last few years I've changed my thinking of it because I think that's almost too much thinking.

I think really what they wanted to do...

No, really, I think what they were looking for was the guy that would get that...

I think that was too much thinking.

You start thinking too many things.

This guy is wearing blue, and this guy...

You overthink it.

I think what they saw was, this is the right man to land on the moon.

Whether or not he was gregarious, whether or not he was shy, whatever those personality traits were, he was the right man because he understood what was happening, he was going to focus on that job 100%, not be distracted, and maybe that has partly to do with the fame-seeking, but I think really he was chosen not for that, for the personality part of it, but because he was the right man to do that job.

So did they choose who actually got out of the capsule first?

But he was the mission lead as well.

The commission commander.

Yes, so it wasn't because he was commander that he got to go first.

They actually made the choice, like, you're going to be the first to step foot on the moon.

And your commander.

And your commander.

Like, those are two separate things.

You think?

Yeah, for example...

It could have been like in Star Trek.

You go check out the glowing blob first.

Buzz, you check, see that glowing thing?

Report back to me.

Right.

And then I'll step off.

And that's traditionally...

You're going to be the Black Ensign from the Enterprise.

But that's the way we did it.

Now that you're saying it, that's why I spacewalked, apparently.

Because that's what we would do in the shuttle program, the commander and the pilot would not go out and spacewalk.

The mission specialist would.

And one of the underlying reasons was...

Just to be clear, mission specialist is someone who has an expertise, usually a scientific and engineering expertise, brought into the service of the mission.

Correct.

So you're not flying a plane...

We're not there for landing.

We're not going to land.

I mean, we're part of landing, but we're not actually going to land.

Right.

Because the idea is, what happens if your commander goes out and doesn't come back?

Who's going to land?

Right.

Okay, if you go out and don't come back, you can still land.

I hate to put it that way, but yes.

I'll put it that way.

We used to brief our spacewalks.

There was a lost crewman.

There was a line.

Everything you would check, like, all right, this is in place, this check, that check, that check.

And part of the briefing was lost crewman.

And lost crewman was a procedure we had to go rescue a guy that comes lost.

And what we would do, sort of kidding around, was lost crewman, don't worry about it, we got three more.

That's what we did, because we had four spacewalkers.

So that was like the joke, and we'd all laugh under the line.

You're kidding.

Come get me.

But we were going to do that if we needed.

What were we talking about?

Oh, the commander, who went out first?

And traditionally, I think in Gemini, what they did was, is that the commander would not go outside.

Two astronaut capsule.

Right, and that's when they first spacewalked.

Ed White was the first spacewalker, and Buzz was one of the last spacewalkers in Gemini.

But I think it was traditionally the commander stayed inside.

Thank you.

Mainly the commander, I think the tradition was the commander stayed inside, and it was the pilot who went out and then came back, because there was only one guy at a time going.

So this was a different case where you're going to have both people going out for the walk.

Yeah.

So, part of the authenticity of the film was there are little details that they didn't have to really care about, but they did.

Yes.

So there's a moment, I happened to own an Omega watch that was gifted to me by Stephen Hawking.

And that's pretty nice.

I don't mean to name drop it.

I was going to say, I just like the fact that you didn't name drop it.

I've got one too, but I had to buy it myself.

I have a Stephen Hawking watch too.

He just doesn't know I have it.

Well, you got his watch.

Yeah, he was just walking around just like, have you got a Stephen Hawking watch?

So, it was gifted to you by you.

Exactly.

So, no, I got the Stephen Hawking Award for Science Communication.

So, it's only like a year old.

But this introduced me to Omega watches.

Omega was the first watch on the moon.

They were chosen by NASA after NASA got all the premier watches.

Rolex, Breitling, whatever the top watches were of the day.

I wonder if they threw in the Timex.

I don't know, just to get America in there.

I bet so they did.

It's probably still on the moon taking a lick and keeping on ticking.

Nobody remembers that advertisement.

It was a wind-up.

In fact, the moon watch was a wind-up.

So they put them all in black boxes each and scrambled them, and then shake them, bake them, heated them, radiated them, and at the end of the experiments, the Omega still had the correct time.

So Omega is our watch.

They still milk that today with their advertising.

But in any event, in this festival that I attended, the Starmas Festival that Hawking is an organizer of, Omega was one of the sponsors, and so this became the watch.

It's engraved on the back.

But I saw a watch that looked very much like this on Neil Armstrong's hands in the movie.

It's right there.

I'm wearing it.

You're wearing it.

I'm showing the camera.

Did you get this from being an astronaut?

No, no.

So we had Omega watches on the shuttle, and the way it was explained to us, like how they won that competition, was the crystal.

Apparently, that crystal that they had on top was almost impenetrable.

And you could do whatever you wanted to it.

It wasn't going to crack.

So particles are a problem.

So that's why I think it's one of the best.

And with moon gloves, how do you wind a watch?

Well, I think you have to wind it ahead of time.

We had a different Omega that we had.

We had a different...

We wind it ahead of time.

We had a different Omega for the shuttle.

This is the moon version.

I had a different one that I had to purchase.

Now, Omega was willing, I think, to give us these watches for free, but it was a government program, and NASA said, not so fast.

So we had to buy our watches, but we were able to purchase them from Omega and then fly them.

I'm not wearing my shuttle watch, and I'm wearing a moon watch that, yes, I had to go into the Omega store and buy.

Man, that is messed up, man.

No, it's okay.

Otherwise, you can be bald.

It's the right thing.

It's the right thing to do.

That's how you want it to be.

You don't want it any other way.

No, no, it's the right thing.

We got to take a break.

We got to take a break.

You are listening to, possibly even watching StarTalk.

This is our first man edition, celebrating the life and the first steps on the moon of Neil Armstrong.

We're back on StarTalk, First Man edition.

And I've got, First Man, who's the First Man?

Neil Armstrong, First Man on the Moon.

Got our friend of StarTalk, Mike Massimino, he's been in space twice.

One of them to repair my Hubble Space Telescope.

I love you, man, for that.

Thank you.

You're welcome.

Chuck, Chuck Nice, co-host Chuck.

Yes, and I've been in space, I'm still in space.

I'm still in space.

Space out and space, two different things, Chuck.

Two different things.

I was asked back in 2009 to host, to emcee, the 40th anniversary of the Apollo landing.

1969 plus 40 gets you to 2009.

It was in the Air and Space Museum.

It was there, and I forgot, Mike, you told, what I did in front of you, you told, you just-

You moonwalked.

Well, I had, you had every living moonwalker in the audience in front of me.

You said some interesting things, I remember.

No, you said something about being the 40th.

The 40th anniversary?

Yeah, and you were saying how 40 was an interesting number because 50 you might not, and we've lost so many of those guys between then and now.

Wow.

And you did the moonwalk, which was great.

I don't dance in public.

Wait a minute, let's go back to the 40th, because that sounds a little provocative.

Oh, no, so I'm trying to remember if this is when I said it.

40 is an interesting number because in many stories, they don't track it beyond 40.

So, 40 days and 40 nights.

Correct, yeah.

It's not 50 days and 50 nights, it's 40 days and 40 nights.

Jesus got 39 lashes, not 40, because 40, that's like infinite.

You got to bring that in.

You don't want to kill him, you just want to hurt him.

Oh, that's the one lash that would have did it.

What else?

Just the number 40 shows up, especially biblically.

Yes.

There you go.

Okay.

And it's a, so when you pass 40, it's like more time than historically people reckoned.

Okay.

You sort of, you know, one through 40 and then infinity beyond that.

And so beyond that, it's like, okay, is it still there for us to remember or do we have to be reminded of it?

Whereas if it's within 40, you can talk about it.

People were alive, they were conscious, they were adults.

They were, so.

That makes sense.

That's two generations basically.

You're stepping into the next generation.

You're stepping into the next generation.

And that makes perfect sense.

Okay, good.

So I think that set the mood at the time that this was a really special night.

In this event afterwards, StarTalk was in our first year.

And I said, this is a target of opportunity for me to get a bunch of interviews and we can make a show out of this.

So I waited till the event was over and we had a reception and all of this.

And I got interviews with various key people in the space program at the time, as well as some old timers like Neil Armstrong.

And he never gives interviews.

Yeah.

Have you ever seen him interviewed on TV?

No, that's one of the things he's known for is not, is not being a big talker.

Here's why I think he granted me the interview.

Because the moon walked?

I first met him when I was 14.

Oh.

Onboard the SS Canberra, en route from New York City to the coast of Northwest Africa.

To observe a total solar eclipse, the longest in the century.

And he was one of the various sort of important people brought on board.

First, they would enjoy the eclipse, but also they were there for the rest of us to interact with.

And this is 1973.

And you're 14?

I'm 14.

Are you by yourself?

Yeah, I'm by myself.

I lied.

What did you do?

Yeah, I was gonna say, what would you do?

Did your parents know you were going on this thing?

They're like, wait, my parents didn't even let me take the subway back then by myself.

Why does that see you man have legs?

You went on a cruise with Neil Armstrong to see an eclipse when you were 15.

I brought my telescope with me that I bought from Dog Walk.

I got to go to a ball game and I was excited.

Dog Walking Money, I had my telescope, I had my camera.

Wow, awesome.

There were 1,500 people.

They took off all the shuffleboard and the lounge chairs and it was a forest of tripods.

The whole ship was a scientific floating vessel.

Wow.

And he was there, that's when I met Isaac Asimov and various other sort of heroes.

If you're a geek kid in the day.

And you were a king geek, okay?

You were king of all geeks.

Because a geek kid is just like, I can't believe I just got this new trading card.

Are you kidding me?

So, he's sitting alone at the bar.

And this is one year after the last mission to the moon, which is 1972.

It's four years after he walked on the moon.

And he's alone.

I said, you know, Mr.

Armstrong, and I had my ship program with his picture and the thing.

And I said, would you mind signing?

I don't know, could you sign?

I think, and so he signs it.

And I just said, thank you.

When I next saw him, I showed him that, that I was on this vessel.

And I think he, I don't know, I don't want to project what he might be thinking, but I think he saw that I became somebody.

No, there's an instant connection.

You come to me all these years later with a sign program from a ship that you stowed away on, so that you could go to North Africa and watch an eclipse.

That's pretty cool.

I would rather the story ended with him going, pull up a stool, kid.

But that's what it takes, kids, to get an interview with Neil Armstrong.

You know, you're not just going to, well, hey, I've got my press credentials here.

No, that's not working.

So, and it was brief, but I have it.

And you'll see he's not a, you know, he's smart and calm and measured.

And let's check it out.

This is my interview with Neil Armstrong, very brief though it was.

Neil Armstrong, commander of Apollo 11.

How old were you 40 years ago today?

Was 38.93.

Excellent.

I love it.

And of the entire Apollo era, what's your most indelible memory?

And it could be your own walk, but if not, I just curious.

Most indelible memory was approaching the moon and flying through the moon shadow so that the moon was eclipsing the sun and we could see the corona all around the moon.

It was not circular, it was elliptical, which was a big surprise.

I understand that.

And then we could see the moon, the dark side of the moon, of course, illuminated by earth light.

And we could see the craters and the valleys and the plains in a blue-gray, three-dimensional view that was spectacular.

The image had to be spectacular.

And remarkable, but imperceptible to a camera, but the human eye was wonderful.

And the last question, what do you think NASA should do next?

I'm a supporter of the NASA plan and I'm...

It just needs more money, I suppose, but the ideas are there.

Yeah, I think the approach they're on is a good one.

I like that.

It's a very pilot, the approach.

They're a little below glide, but they're going to get there.

All right, Neil Armstrong, thanks for those three questions.

You guys never interviewed and I felt like I was even taking too much by asking just those three questions.

And I'm kind of giddy.

He was really into that second, what's the indelible...

You could actually...

I can almost feel him looking at the moon.

Experiencing it.

Yes, it was really very visceral, his recounting.

Consider that's nothing you're going to get on this side of the moon.

So it had to be the back side because he would have studied all the maps and the pictures and everything.

One of the things that I noticed with the movie, one of my favorite scenes, first man movie, was that you're able to see what it looked like.

And I think they probably did it pretty accurately because the film that we had back then in 1969, we had some, but especially the approach and the landing, there were cameras kind of looking out that triangular window and the dust kicks up, but you really don't get an appreciation for what it was like to see outside.

Can you imagine now if we were able to do that with a bunch of GoPros or whatever they would stick on, high-def cameras, we would see that moonscape and probably even the night passes.

There'd be a GoPro every foot.

Probably so, right.

And make the whole ship out of GoPros.

And even in the low light level on the other side, I'm sure they would have been able to do something because just recently now we can get great images of the planet at night from station, for example.

And if it wasn't clear, his point that the eye catches it but the camera doesn't is because the eye in one glimpse can get a very high dynamic range.

So the moon can be very dim, but the solar corona can be very bright.

You can see all that at once.

Where the camera is going to commit to either the bright corona or the dim thing, but you're not going to get both.

And he's experiencing both.

That description he gave you allowed us to picture what it was like.

There's no real good video of that, but his description of it is what we have to go with.

But you can feel that he'd rather just not be interviewed.

He'd just want to go on his way.

But is that really the best person to represent the fact that you have walked on the surface of a celestial body?

That's a good question.

I heard Mike Collins at Neil's memorial.

Mike Collins, the third astronaut who didn't get to go down to the moon.

Yeah, he orbited in lunar orbit in the command module while Neil and Neil Armstrong buzzed on the moon.

I heard him speak at the memorial.

I don't want to misquote him.

But at Neil Armstrong's memorial when he died and they had a memorial service for him at the Johnson Space Center.

And he talked a little bit about that, about him being maybe shy and cerebral or whatever.

But he was like, well, why wouldn't you want that?

This man who was so qualified, who did such a great job, why would you want him to be anything different than who he was?

And I think that he was the right man to land on the moon.

And I think that was what they were most concerned with.

Because, no kidding, they weren't so sure they were coming back from that mission.

They weren't so sure they were going to be successful.

Apollo 12 and 13, 11, 12 and 13 all had the same mission.

They all trained for the same mission.

Because they weren't so sure 11 was going to be successful.

And 12 had to come up with something quick, which was different than what they did on 11.

But they all trained for that same mission, because they weren't so sure 11 was going to be successful.

What you're saying is if 11 failed, then next up, you try it.

You're next.

If 12 failed, you're next.

13 was going to try it.

And that can be in a few different ways.

Not so that they wouldn't come back alive, but they might not get down to the surface and come back.

They would have to abort and then come back to Earth.

So it was really important for them to try to get the right guy to be the first guy.

And that's what they went with.

Who's the best guy to pull off the landing, especially, of this?

And that's where he had ice in his veins.

And by the way, there's a misconception, I think, about the first comments from Houston after he says, Houston Tranquility Base here, Eagle has landed.

Yeah.

Okay.

Which means, of course, the first word of the first comments from the moon is Houston.

There you go.

A plug for Houston, Texas.

My former home.

Planet Houston.

So, Houston Tranquility Base here.

That's the way we talk.

Actually, there were some other comments, the contact light and other things.

Yeah, contact.

Right.

But Houston then says something like, congratulations, you have a bunch of guys down here who are about to turn blue.

Yeah.

That was Charlie Duke.

Okay.

Yep.

You think they're saying that because they just landed on the moon.

That's not why they're saying it.

They were holding their breath?

That's not, yes, they were holding their breath, but it's not because they just landed on the moon.

That's not why.

Okay.

Why would, okay, so why were they about to turn?

Wait, they were Smurfs.

No, I'm kidding.

Because Neil was not happy with the original landing spot.

And he only has a certain amount of fuel to prevent himself from crashing down onto the moon.

This is keeping them buoyant.

Nope, too many boulders there.

Nope, too many boulders there.

And you see the fuel come down.

Wait a minute.

And then he keeps going.

I think I'll go over there.

And my boy is smooth.

Yep.

It's like he's looking for parking in Midtown.

He can't park there.

I can't park there.

Baby, baby, you think I can fit in there?

No.

Try over there.

But if you don't make it, you got to go home.

So then he finally finds a spot, lands.

There's like one or two percent fuel left.

That's what they...

Because if he got...

If he went to zero...

Because if he lands with fuel in a place that he could crash because it's not level, that's bad.

If he keeps looking, he can't get home.

If he keeps looking and runs out of fuel, he'll crash because he runs out of fuel.

He may have a board.

Oh, they could have a full board.

I don't think you would.

You just jettisoned at that point.

I think that's what they would have done.

Forgot about that.

Which is not a good deal either.

So he would just...

And they capture this in the film in the tension.

So that's why everyone at Mission Control was freaking out.

Oh.

Because the mission might not complete.

Not because, oh, we're happy you landed.

Yes, we're all happy you landed on the moon, but we're happy you landed on the moon alive.

Yep, yeah.

He was down to one...

He had a low fuel light came on, 30 second fuel or whatever it was he had.

And in the cadence of...

Which is depicted in the movie.

But the cadence of the calls he was getting from Buzz.

So many forward, so many down.

I think he was talking about rates at that point.

That's right, it's this way and down.

Forward, 5-4 to give him an idea of how fast he was moving forward.

Because he's all out the window I would think at that point.

And that's the cadence of him coming down there.

Wow, that's fascinating.

So I got to agree, if your mission is to succeed, that has higher priority over any social profile the person is going to have.

Or public relations.

You succeed first and worry about the rest of that later.

His friends, his colleagues have...

John Young was still an astronaut when I became an astronaut and later walked on the moon.

Alan Bean was his office mate and his colleague as well.

Another moon walker.

And I've heard him and those other guys say Neil was the right guy for the job.

If they had a pick out of who they knew was going to get that job done, it was Neil Armstrong.

Alright, we're going to take our next break.

We're talking about first man.

That's the first man on the moon, Neil Armstrong.

We're back, StarTalk, first man edition.

We're celebrating the life of Neil Armstrong and the moon landing and his first steps.

Got Mike Massimino, Mike.

Neil.

Very good.

I'm just still laughing, chuckling at your first tweet.

Oh boy, yeah.

But was it, golly, I'm in space, was that what it was?

Lunch was awesome.

Lunch was awesome, okay.

Maybe they misunderstood it, but thought you meant lunch was awesome.

No, that was, it was the first day in space, no lunch yet.

You're not feeling out with that, great.

Lunch was awesome the next day.

That's when I wrote about the macaroni and cheese.

This first day was lunch.

So at NASA, there's a famous, colorful character called Gene Kranz.

And he's the one who is portrayed famously in the film Apollo 13, saying what?

Failure is not an option.

Failure is not an option.

I bumped into him.

Did he say that in real life?

Yeah, oh yeah.

Well, that's the legend.

Okay, cool.

Okay, and I bumped into him with a microphone in tow, first year of StarTalk.

I'm getting all the interviews from all these space folks at this celebration of NASA's 40th anniversary for landing on the moon in 2009.

Let's pick up with my conversation with Gene Kranz.

Here with Gene Kranz.

Failure is not an option, Gene Kranz.

That's your middle name now?

That's been a good game plan for most of my life.

I really came into failure as not an option.

Well after, I started the business of Stars and Stripes Forever.

When I was going through flight training, I had a very bad night.

My first night solo, I suffered almost disabling vertigo.

And finally got back landed and the next evening you got to go out and do it again.

And there's a story about you got to ride the horse that threw you.

I was fortunate that as I was sweating it out, chain smoking, lucky strikes, the flight line public address system came alive.

Checking it out for the Saturday parade and they played the Stars and Stripes Forever.

I picked up my parachute, aced that night flight.

In fact, I aced the business as a cadet graduated, went to fighter weapons school.

And from that day on, every day of my professional life started with the Stars and Stripes Forever.

There's a inspiring.

Everybody's got something to get them going.

For most people, it's a cup of coffee.

Neil, I start off with a cup of coffee, too.

But the Stars and Stripes, it was interesting.

I look for something that very slowly builds the energy, builds the crescendos, such that when you hit each day's work, you're at the peak performance and you remain there throughout the day.

I found out that basically, from my standpoint, psyching yourself up is the key to success, believing that you can, believing that you will.

And then when you fall down, believing that you can pick yourself up and start all over again.

I want to ask you three questions.

You ready?

How old were you 40 years ago today?

I was 36 years old.

You were a baby.

I was a baby.

My team's in mission control, average age 26.

The majority of those were kids fresh out of college.

They had a couple years training.

They grew up in the Gemini program, early Apollo.

They lived through the disasters of Apollo 1 fire and they became tough and competent.

And that was the fuel, the energy for the fire that took us to the moon.

What is your most indelible memory from the entire Apollo era?

Neil, I would say the most indelible thing were really many things.

They were the personalities of the people.

I had young kids that came in fresh out of college who had this dream of space.

I had the engineers come in who developed the initial trajectory work.

John Llewellyn and Carl Huss and Tequan Roberts who were absolute pure mathematicians.

They reveled.

I mean, this world was life to them.

Basically, I was a dumb engineer.

I was a dinosaur, but my business was not to know the work that they did to the level they did.

My job was to be able to ask the right questions and watch the clock.

I counted cadence for mission control.

So most people who only see the astronauts have no concept of all this that's going on behind the scenes that's making it happen in the first place.

Well, the mission control team has the responsibilities for planning, training and operate.

And when we have problems during the course of the mission, we have to come up with solutions that allow you to continue with the plan that you had.

And if that is not possible to come up with another plan that is just about as good.

One last question, what's the primary goal you think NASA should have going forward?

I believe NASA should go back to the moon and then on to Mars.

I believe that it's very important.

You know, to me, the moon is like the boundary in the Mississippi River.

We've been across there a few times.

But really think about the development that took place out west.

Think about Lewis and Clark going out to the Pacific.

Think about the business of exploration.

And those things that we learned and developed and discovered out there.

But most importantly, I think it is a human thing.

Exploration is a process that must be in every person's mind.

It has to be part of their personality.

It has to be the kind of thing that makes them want to get up and go to work each day and discover.

So, back to the moon, on to Mars and beyond.

That's right.

I'm go for it.

Go for launch, Neil.

There's only one Gene Kranz.

I effing love that guy.

I love him.

You want that to be the voice in Houston when you were in the universe somewhere.

I want that to be the voice of everything.

That guy is amazing.

Will we be okay?

You will be fine.

I'll tell you what you're going to be.

You're going to be absolutely terrific.

That's what you're going to be.

Neil, I want to tell you, I like coffee.

I like my coffee as black as space, but I use the stars and stripes as the sugar in my coffee.

I wake up every morning to coffee and stars and stripes.

It's tremendous.

That's American.

That guy is awesome.

That dude is awesome.

He's really the guy that you want looking out after your ass, is what it is.

Really?

When you're up there in space, you want to know that the man in charge is going to make sure you're okay and is going to consider it most important.

He didn't mean God in that case, the man in charge.

He meant Gene Kranz.

I meant Gene Kranz.

No, the man in charge, what I really mean is the flight director.

The flight director is the person who oversees the team that is looking out for you.

That's what I always felt.

You have a certain connection with your launch flight director in this case.

I think Gene was the launch flight director for, and Mike Linebeck was the guy that launched us out of KSC and then our launch flight director, my second mission, Norm Knight and Tony Cicacci was the guy during the orbit and there was those, they, I think, followed.

We had an orbit guy.

We had an orbit guy.

There was an orbit guy for Apollo 11 as well, right?

But they all followed, I think, in Gene's steps and that was what you wanted.

You wanted someone who was there.

So the right stuff wasn't-

Make sure you were coming back.

The right stuff wasn't only the folks who flew, it's the folks on the ground.

Yes, and they take it just as personal when something happens as anyone else involved.

Their job is to bring you back more than anything.

Now I know where that saying comes from too.

You want a guy like that.

What's that?

Now I know where that saying comes from.

What's that?

Failure is not an option.

People say that all the time.

You didn't know it was him?

I thought it was like a movie quote.

It's a movie quote because it's quoting him.

It's the title of his book, I think, as well as Failure is Not an Option.

Oh man, that is-

You gotta go get this book.

I'm gonna go get him.

Get it on audio books.

Exactly.

I hope he's not crazy.

Chuck is like, his eyes are popping out of his head.

I love that guy.

Dude, he's like 76 right there when you talk to him and even at 76 when you're talking to this guy, he sounds like a 22-year-old kid.

Right, with excitement.

I love that.

So Mike, did they level with you what your risk of not coming back was?

Because they made a point of this in First Man that these risks are real and we saw all of them.

We saw others die.

Apollo 1, three astronauts died on Earth.

There are test pilots who have died.

So this is a specter over your choice to participate.

Yeah, I think they tried to be as accurate as they could.

Yeah.

And I remember it more because I flew on Columbia, the mission right before we lost Columbia, and then I flew again after on Atlantis, both shuttle flights.

And I don't remember if what the there wasn't as much talk beforehand.

I guess it wasn't maybe as much on our mind as it was after the accident.

We lived through that.

After the Columbia accident.

After the Columbia accident.

But the number I remember being told was about one out of 75 chance.

And it weren't saying we want you to know this number.

It was more like this is our new calculated probabilities.

I was told it was like one in 50.

Well, I think there was one out of 75 and that was total destruction.

That's loss of crew and vehicle.

That's everyone's dead and the vehicle can't be used again.

There are other odds that may be of hopefully dead.

They folded the odds of reusing the vehicle with the odds of you coming back alive.

That sounds pretty crass.

Yeah, but it's true.

I mean, I hate to put it that way, but when we lost Colombia, we just didn't lose our seven friends.

We also lost the spaceship and what happens to the program.

So there's a loss of crew and vehicle.

Now losing, but it's not so much about, it really isn't crass, I don't think, because you can lose the vehicle but save the crew.

So if you have an abort with the shuttle and it ends up in the water as you abort, hopefully the crew gets out alive.

So it's a combination of loss of crew and vehicle was about one out of 75.

And as it turned out, we had two accidents at 135 flights.

That's probably how they came up with that number, quite honestly.

But it was one out of 75 total loss.

And do you think about it at all when you're, or are you just too busy doing your appointed duties to even let it cross your mind?

I took a flight back to New York from Detroit yesterday morning and the whole time I was like, God, I just hope these people know what they're doing.

Sometimes you're worried more on a commercial flight than you are doing anything else.

I mean, we had a, yeah, absolutely, I did.

I don't know if everyone does, but I knew that there was a very good chance that something might, you might not be coming back.

And I think in some ways that's a good thing to know.

And the movie captured this poignantly with his relationship with his wife and his kids.

Yeah, and I think they also showed the after it was successful, how wonderful it was for everyone to have accomplished this.

That we have succeeded.

That we have succeeded.

Alan Bean tells us this story that after his, after Apollo 11, after his mission, it wasn't, the whole world, his impression was the whole world, it wasn't like you did it or the US did it, but we did it.

We, the human species did it.

Yeah, that motto, they came for all humankind.

Let's change it a little bit, right?

For all humankind.

I think that's the way everybody felt.

We come in peace for all humankind.

Yeah, and that's the way I think people felt about it.

It was an accomplishment that humans, that showed what we could do and the whole world was a part of it.

And they felt it was an accomplishment for the world.

I had the privilege and honor to be invited to Neil Armstrong's funeral service in Ohio after he died.

And the moment was solemn, of course, but it was also celebratory.

There were reflections on Neil as a person.

And one thing that came across was, yeah, Neil was the right guy for this job.

And because if he started grandstanding this achievement, then it would be like he landed on the moon.

But in fact, we all landed on the moon.

It's our collective first step on the moon.

Tens of thousands of engineers and scientists and hundreds of millions of taxpayers.

We landed on the moon.

And what did he do when he was done?

He became Citizen Armstrong again.

He became a professor.

He went back to Ohio, where so many astronauts have come.

He became a professor and shunned interviews.

And I'm reminded it was a Roman emperor, Cincinnati.

Cincinnati, after whom Cincinnati is named, Cincinnati, Ohio.

That's where he taught.

He came to become emperor, and when he was done, he went back home and continued as a farmer.

Didn't exploit the fact that he ran all of Rome.

He didn't grandstand that fact.

He was called into service.

He gave of himself his time, his energy, sacrificed whatever was necessary for his home life.

When he was done, he went home.

That's what Neil Armstrong did.

He came home to us all.

It's pretty cool, man.

I have to say, I understand it for Neil Armstrong.

Cincinnati's got a problem with him.

What's your problem with Cincinnati?

I'm just saying, you were ruling all of Rome and then you became a farmer.

What's your problem, buddy?

Are you kidding me?

The Roman Empire?

You were the Roman Empire at your disposal and you went back to farming?

It's a reminder that some people want power for power's sake, rather than power to lead and guide others in a time of need.

That's a cosmic perspective.

We got to end it on that.

Mike Massimino.

Thank you.

Always great to have you, man.

Thanks for doing this for Neil Armstrong.

I think the things you said, especially at the end there, I think those are the lessons we can learn for all of us, no matter what your occupation is, how to approach things.

He was my hero as a little boy because he landed on the moon, but getting to know him a little bit as a person and learning more about him, that's when you realize what a true hero he was.

So thanks for doing this and having me a part of it.

And Chuck, Gene Kranz is his hero now.

I'm just so happy for this show.

Not the Cincinnati guy.

Cincinnati's no.

Cincinnati's no.

Gene Kranz forever.

That is all I'm saying.

This has been Star Talk.

Most of you are listening, some of you are watching.

I've been your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

As always, keep looking up.

Come on.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron