This week, astrobiologist Dr. David Grinspoon sits in while Neil is off working on the new COSMOS series for FOX. You might remember him as our guest planetary scientist from the Mars Curiosity Rover team at StarTalk Live! Satisfying our Curiosity about Mars and StarTalk Live! Exploring Our Funky Solar System, but he also works on ESA’s Venus Express mission. In other words, Dr. FunkySpoon is the perfect guide to answer your Cosmic Queries about Venus… with a little help from comic co-host Leighann Lord. You’ll hear theories on why Venus rotates so slowly (its year is shorter than its day), and in a different direction than Earth. Find out why exploring Venus has been so much harder than Mars, in spite of the long-lasting Soviet Venera program, and the challenges to creating rovers and space suits that can withstand Venus’ crushing pressure (90x Earth’s) and searing heat (nearly 900 °F). Learn about Venus’ runaway greenhouse atmosphere, how it got that way, why it has no plate tectonics, and even the possibility of life on this inhospitable planet orbiting so close to the Sun.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Now. Welcome to StarTalk Radio. I'm David Grinspoon. I'm an astrobiologist, and I am sitting in as host for Neil Tyson, who...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Now.

Welcome to StarTalk Radio.

I'm David Grinspoon.

I'm an astrobiologist, and I am sitting in as host for Neil Tyson, who is not here.

He's off in the cosmos, filming his show, Cosmos.

And I'm joined by my co-host, Leighann Lord.

Yes.

You know, I'm so glad you introduced yourself, because I'm sitting here going, Neil, you have really changed.

You are not how I remember you at all.

Yeah, no, I'm not fooling anybody.

I'm not even gonna try to.

Nobody could actually fill Neil's shoes.

Fortunately, nobody has to, because we've still got Neil.

He's only gone for a while.

But it's nice to have a guest sort of sit in the big chair.

Yeah, well, it's fun to be here, and it's great to meet you, Leighann.

Nice to meet you as well.

And have the opportunity to talk this afternoon.

We're actually doing a segment of Cosmic Queries.

My favorite segment.

And the topic is actually my second favorite planet, which is the planet Venus.

I hear you're an expert on that.

Is that true?

Well, it's something I've been interested for a long time.

I've written a couple of books about Venus.

I've never actually been to Venus, but you could call me an expert if you wanted, I suppose.

You know what, if you've written a couple books, I think you've earned the title.

Well, thank you, thank you.

I'll take it, I'll take it.

Very good.

So Cosmic Queries, I love that because it always gives our fans and folks an opportunity to write in and ask those burning questions and actually get them answered.

Yeah, it's always fun to know what people wonder and what they think about these subjects that I've been thinking about for so long.

And every once in a while, somebody stumps you or makes you go, huh, never thought about it that way.

And that's really fun too.

But then that's an opportunity for another study.

It's like, hey, we didn't think about that.

Somebody write up the grant papers.

We need more grant money, call NASA.

Call NASA.

Oh man, that's great.

Well, if you're ready, we can jump right in with questions because we have many, because StarTalk fans are awesome.

And we'll jump in with the first one from Garrick Stemo.

And Garrick, man, I apologize if I mispronounced your name and even reassigned your gender.

And Garrick would like to know the history of what we know about Venus and how we came to know it.

Dude, that's right up your alley.

Yeah, well, gosh, you know, okay, let me launch into an hour long lecture now.

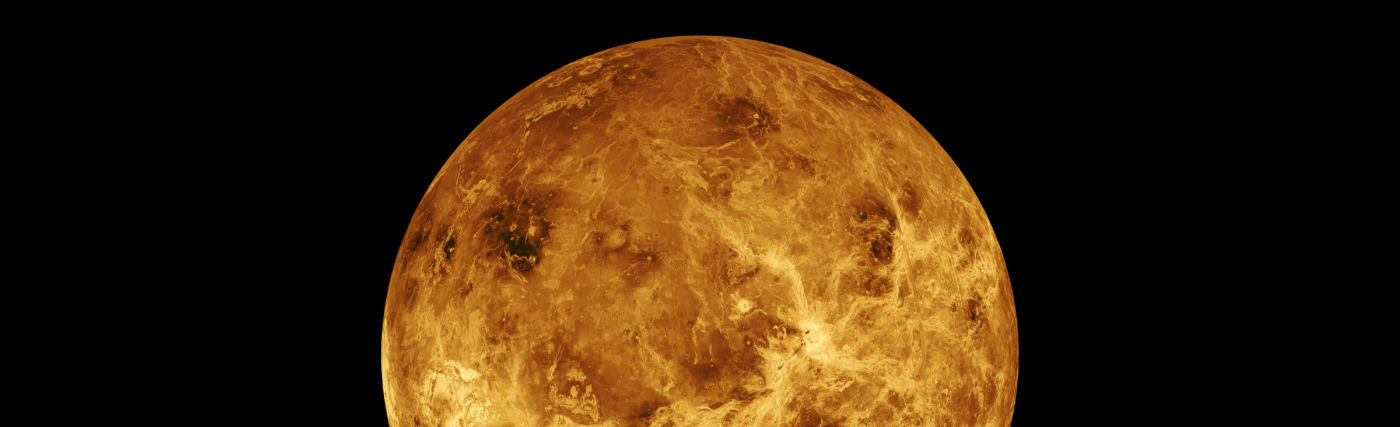

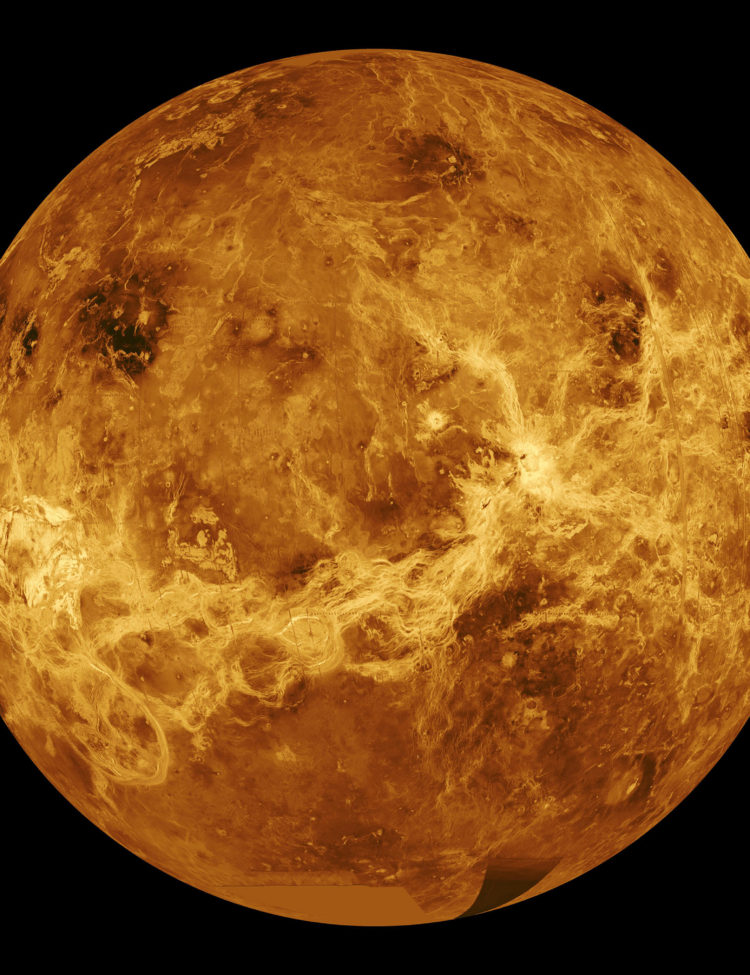

But I mean, in short, we knew about Venus long before we had anything like space science because Venus is the brightest object in the sky after the sun and moon.

And so humans have seen it and noted its motions and been fascinated by it for, you know, as long as we've been humans, including some quite sophisticated knowledge by people like the Mayans and other, you know, indigenous people that really observed Venus very carefully and knew a lot about its motions.

Some things we've forgotten that scientists today don't even know.

People knew a long time ago.

And then of course, in the age of telescopes, we did all kinds of observing and learned that it was bright and had clouds and was the same size as the earth.

And, you know, started sort of, there's this whole phase of using telescopes and learning that at least in some ways, Venus is very much like the earth.

And then there's of course been the whole phase of spacecraft where we visited with landers and orbiters and entry probes and started to really learn about Venus as a place and learned that in some ways, it's not like the earth at all.

It's the same size and nearby, but its environment has veered off and evolved in a totally different direction.

As I can see from some of these very, very poignant questions here that people are asking.

And I'll go on to the next one from Nelson Say.

And he wants to know, and this comes off what exactly you just said, what has caused the runaway greenhouse effect on Venus?

Yeah, so the runaway greenhouse effect, one of the striking things about Venus is that in some ways, it's so earth-like.

It's nearby, it's the same size, it's the same mass formed at the same time.

It's earth's twin, and yet its climate, its environment has gone completely off the charts.

It's so hot there.

It's 900 degrees, almost Fahrenheit, on the surface.

It would melt just about anything.

This microphone would just go into a puddle of metal.

And just so we're clear, we didn't have anything to do with that.

Because humans mess up everything, but we didn't do that.

We cannot be blamed for Venus' climate yet.

I'm taking credit for not getting blamed for that.

Exactly, but the runaway greenhouse that is referred to in the question, that's the idea that Venus started off earth-like as near as we can tell.

It did have oceans and water and was cooler when it was young.

And then as the sun heated up, which the sun has been doing over its history, it passed a point where things got hot enough so the ocean started to evaporate.

As the oceans evaporated, there was more water vapor in the air.

Water vapor is a strong greenhouse gas.

So water vapor in the air makes it hotter at the surface, which leads to more evaporation of the oceans, more greenhouse gas in the atmosphere.

It's a positive feedback.

It runs away.

It gets even hotter.

The oceans evaporate more.

It gets more greenhouse.

And when there's nothing to stop that, it's a runaway.

And probably it got to the point where the oceans literally boiled off and all that water vapor in the atmosphere broke up by ultraviolet light.

The oxygen streamed off, the hydrogen streamed off into space.

And Venus was left ultimately in its current state, which is really hot and completely dry.

So to say this as delicately as possible, Venus is sort of going through menopause.

Can we say it that way?

You can say it that way.

And there's something to that, but it's a menopause that has a lesson for Earth, because it's sort of the ultimate global warming.

Venus certainly has a fever, a really, really high permanent fever.

And it's sort of, do not let this happen to your planet.

It's the extreme example.

That's a great title.

Don't let this happen to your planet.

Something like Douglas Adams would write.

Yeah, yeah.

It's the extreme example in our whole solar system of what can happen with a really extreme case of global warming.

And now, did I hear correctly that it wasn't anything that Venus necessarily did?

This is the sun naturally getting hotter.

Yeah.

I mean, Venus, take Earth and move it 30% closer to the sun, which gives you twice as much sunlight because the sun, you know, the radiation goes as the square of the distance as I know you know.

Oh, yeah.

So move something 30% closer and it gets about twice as much sunlight.

If you take Earth and move it to that distance, this will happen to it.

It will go through a runaway greenhouse.

So it's basically what happens to an Earth-like planet where there's just a little bit more sunlight than we have.

Ouch.

Not enough sunscreen for that, eh?

No, no, no, no.

It would not have been fun to go through if you were one of those creatures living in the young ocean of Venus.

Which, you know what?

I know for a fact, and you don't because you haven't seen these questions ahead of time, that we actually have some questions about that, the possible life forms in a young Venus.

Yeah, well, that's a good one and I'm looking forward to that.

So when we come back with more StarTalk Radio, we will get into questions about life on Venus.

In the meantime, you can go to the website, which is startalkradio.net and learn more about the radio show and learn more about what we're talking about, as if we knew.

And we'll be back in just a few minutes.

Welcome back to StarTalk Radio.

I'm David Grinspoon, I'm an astrobiologist, sitting in here for Neil Tyson.

And by the way, you can follow me on Twitter, at Dr.

FunkySpoon, or my website, funkyscience.net.

And I'm joined here by my able comedian co-host, Leighann Lord.

Hey, I wish my Twitter handle were as cool as yours.

Dr.

FunkySpoon.

Tell us what it is so we know.

Well, my Twitter handle is my name, Leighann Lord.

And since no one but my parents can spell that, I always send people to my website, which is sort of the portal to me, which is veryfunnylady.com.

sofunnylady.com.

What's our next question?

We're talking Venus here.

We are talking Venus.

And to pick up from the last segment, we were talking sort of, was there life on Mars?

And Matt Ely has a question.

What organisms could survive on or underground in Venus?

Well, okay, the basic problem with organisms on Venus, the way it is today, is that heat, the extreme heat of Venus.

That 900 degrees.

That it's almost 900 degrees Fahrenheit, and it's, you know, organic matter, the stuff that we are made out of, does not survive at those temperatures at all.

So life as we know it, made out of organic molecules, absolutely does not exist on the surface or underground on Venus, because underground it's worse, by the way, it just gets hotter.

You know, planets are hot on the inside.

We don't actually know the details of Venus's inside because we haven't had the kind of missions that can measure directly the geophysical measurements to know the details, but we know that it's got to get hotter as you go underground because that's just basic physics.

That's what planets do.

So you might have some more exotic kind of life.

People have talked about science fiction writers have considered, you know, silicon-based life, rocks.

I believe that's a question somewhere in here.

Someone wondering, you know, because of Venus's temperature and elements and whatnot, you know, or liquid or solid, depending on the temperature, is that an argument for silicon-based life as a possibility on Venus?

Well, certainly I would say that we don't know enough about the possibilities for life in the universe to rule out other chemical systems.

It's easy enough to say, well, life has got to be carbon-based because that's the only thing we can think of that would work.

But is that because we can't think of another system, like we're not smart enough, or really because the universe doesn't dream up?

Generally, the universe surprises us with what it dreams up, and then we, with our intellect, figure out after the fact, oh, of course it had to be that way.

So I wouldn't rule out other kinds of life.

And silicon, you know, there's some problems.

Silicon bonds tend to be really stiff the way silicon bonds to other, you know, er, er, er.

So silicon bonds are voguing.

I love that.

They're Roboto, you know, Mr.

Roboto.

Whereas carbon molecules, carbon bonds are kind of like, eh, you know, and they flop around, and that's the molecules in us take advantage of that flexible structure to do the work, the molecular work of our cells.

So I'm not sure about silicon-based life, but I wouldn't be so arrogant as to say, absolutely, we can rule out any kind of life.

But it would have to be a kind that we don't know about.

There's other parts of Venus, not on the surface, where I suspect there might be possible life.

Even though it's hotter?

Up in the atmosphere, up in the clouds, where it's cool and breezy.

And moist, and the kinds of environments that life likes.

Now, in the very beginning, when you were answering this question, you made it clear that today, no way, it's just too hot.

But now what about a younger, more robust pre-menopausal Venus?

Yeah, exactly.

Before Venus had this horrible mid-planet crisis.

When it was a young, strapping, healthy planet, that's an interesting question.

It turns out that Venus, Earth, Mars, all three of these sort of sister-brother planets had very similar beginnings.

We're learning that they all had oceans, warm oceans when they were young.

So it could be that Mars, Earth and Venus all had the conditions for origin of life around the time that origin of life happened on Earth.

So did it also happen on Venus?

We don't know, but everything we know about the early environment of Venus suggests that it could have had oceans, could have had the conditions for life.

And so it may be that Venus started out with a biosphere and then things, you know, it broke bad.

And as the climate went awry for reasons we've already discussed, that it got to a point where life could no longer exist and went extinct or it migrated up into the clouds.

Or into the clouds as your fantasy.

Right, I like that.

So it was possible, not now, but maybe in the clouds.

Yeah, absolutely.

It seems, you know, we need to explore Venus a lot further and learn what that early environment was like, but we have ideas and constraints and some data about that early environment.

It seems as though it was much more Earth-like and Venus lost its oceans and heated up.

And when it was young, there's every reason to believe that it could have had a biosphere.

Oh, very, very cool.

I'm loving this.

I'm learning so much talking to you.

I have another question.

Of course, there are many.

And I do believe, this is from Susan Minoby.

And Susan, I'm gonna go out on a limb here and say that you are a Star Trek fan based on this question.

Oh good, I like the sound of this.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Star Trek, yeah, Trekkies unite.

But her question is, would it be possible to terraform Venus?

Is there a way to seed the clouds and atmosphere and or reduce the solar radiation to try and reduce the greenhouse effect?

And I'm assuming find Spock.

Yeah, yeah, no, it's a great question.

I mean, terraforming the idea of engineering other planets to make them more Earth-like in a place where life could thrive if it's not currently thriving is a very fruitful idea in science fiction and in science, I mean, we have workshops and talk about this and how would you do it?

And I think it's a very useful thing to think about, even for taking care of our own planet.

How would we engineer a planet or consciously control its climate as opposed to unconsciously wrecking its climate?

It's a useful thing to think about.

With Venus, of course, the problem, as the question alluded to, is how do you cool it off?

And interestingly, this is one thing I've done with some of my colleagues.

We do models of the climate of Venus.

And there is a stable state that's much cooler than the current climate.

If you get rid of some of the CO2, the climate can sort of collapse into a state with much less CO2 and where it's much cooler.

So the question is, can you push Venus in a direction and make that climate collapse?

People have come up with interesting schemes, and this is getting Star Trek-y, but if you throw enough asteroids and comets at Venus and kick up enough dust, then you obscure the sunlight from the surface and cool it off and sort of collapse that environment to make it less intensely hot.

And another way people have talked about doing, in fact, Carl Sagan wrote a paper about this, believe it or not, back in the day.

I believe Carl Sagan did anything.

Yeah, yeah.

So Carl proposed that Venus could be terraformed with microorganisms.

If you see the clouds of Venus with the right bacteria that would sort of eat carbon dioxide and breathe out other things, that you could use biology to make the planet more bio-friendly.

So in the long run, as our technology and our command of all these ways of manipulating the world gets more sophisticated, assuming we don't do ourselves in with those same capabilities.

Well, yeah, always assuming that we haven't, yeah.

Then some of these possibilities may open up to us and in the long run, we may be able to manipulate the climates of other planets and find a way to cool off Venus.

Of course, the problem with Venus, in that case, you cool it off, but there's still, there's no water there.

It's, I'm holding this up as a prop.

Yeah, right, right, for our television audience.

For our television audience.

There's, you know, you'd need to find a source of water and that's another reason why you might want to think about crashing comets into Venus.

There's a lot of water in icy storage in the outer solar system.

And if you're really at the point where your civilization can move stuff around in the solar system, you could take a bunch of those comets and icy bodies from the outer solar system, crash them into Venus, and presto, you've got water.

You can go live there.

It's a very scientific term, presto.

Yeah, voila, voila.

And that would somehow be easier than sort of importing it from Earth.

I'm just imagining bottles of water being shipped to Venus.

Yeah, I mean, the problem, if you wanna import anything from Earth, you have to launch it off Earth, and that's expensive, and some stuff's already out in space.

So why not use those resources?

Yeah, yeah.

And you know what?

I would think people would like to crash stuff.

That'd be a lot more fun than just looking at shipping invoices.

And we might wanna keep our water on Earth.

What little of it that's still drinkable?

We're rather fond of it.

We have another question here from Marco Horvat.

And he wants to know, if Venus is about our size, why is the atmosphere so dense?

Great question.

Because yeah, Venus is Earth's twin, same size.

Why don't they have the same atmosphere?

Well, Venus has this thick, thick CO2 atmosphere that we already mentioned.

And on both Venus and Earth, there are a lot of volcanoes that are constantly belching out CO2 into the atmosphere.

I didn't know that.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Yeah, it's one of the main sources of CO2, you know, other than us on Earth.

And on Venus, it is the main source.

And on Earth, over the long run, CO2 is removed from the atmosphere by chemical reactions that depend on water.

If you remove the water, the CO2 gets stuck in the atmosphere.

And that's what happened on Venus.

We talked about the runaway greenhouse effect.

Once the oceans boiled off, the volcanoes kept going and kept pumping CO2 into the atmosphere.

But there was no way for the CO2 to get removed from the atmosphere by those chemical reactions that happen on Earth that depend on water.

So while the CO2 at that point got stuck in the atmosphere, and if anything, that just makes Venus hotter and it gets sort of pegged in the red zone and stuck, it can't escape from that condition.

And that is ultimately billions of years from now what will happen to Earth as the sun continues to warm up.

Nothing to lose sleep over.

It's going to be a while, but that's the ultimate fate of our planet is what happened to Venus a long time ago.

Well, went ahead.

Yeah, exactly.

So we'll be back in a few minutes with more StarTalk Radio.

StarTalk Radio, I'm David Grinspoon, astrobiologist, sitting in for Neil Tyson, I'm here with Leighann Lord, and we're talking about Venus, answering your questions.

And the questions, I love this, I love that the Twitter family is such an active StarTalk fan base.

And we have a question from Richie Ryan at Richie underscore Ryan at Twitter, and he wants to know, does earth pollution have the ability to cause a greenhouse effect with atmospheric pressure on the scale of Venus?

Like even if we burn everything, would that come close to the amount of CO2 in Venus?

Yeah, it's a great question.

And actually it's a subject of some current debate among the community of those of us who model climate on other planets with earth models.

If we did the worst case scenario, burned all of our coal, all of the tar sands, fracked the earth to pieces, got every last bit of fossil fuels out, frack it all and burned everything, could we push earth to a Venus-like state?

And we actually don't know.

There are different opinions about this.

And in some sense it's academic because even if we didn't push earth literally into a runaway greenhouse where the oceans went away, if we did that, we would push earth easily beyond the point where we could live.

In other words, it's a much narrower range of conditions where human civilization and even where life can exist on earth than the range where you have to go to that extreme of pushing earth into a Venus-like condition.

But I was at a meeting last summer where there was some debate about this.

And some of the scientists who, there's a guy, James Hansen, very famous NASA climate modeler who's really been sounding the alarm about global warming.

And his calculations suggest that if you put all the carbon from all the fossil fuels into earth's atmosphere, that we could trigger a Venus-style runaway.

And other scientists have said, well, wait a minute, no, if you consider the clouds and this feedback, because clouds actually form more when there's more water in the atmosphere, but then that helps cool off the earth.

And if you put everything correctly into the model, no, it doesn't quite go to a Venus-like state.

So the honest answer is we don't know.

But it's a really interesting question.

And I think by addressing and trying to answer questions like that, we sort of get smarter about how to predict climate and how to, you know, we flex our climate modeling muscles and it makes us better at thinking about both other planets and the future of our own planet.

Right, and but I'm still sort of stunned by what you said.

We wouldn't even get that far.

We'd be dead.

Oh yeah, yeah.

Long before we could even really see if we could really push it to that extent.

Because you're talking hundreds of degrees of global warming.

And it's, you know, the amounts of global warming that we're concerned about with these studies that people are doing and worrying about what's gonna happen to our civilization.

We're talking about two degrees, four degrees, you know, if you get up to six and seven, then it's like, whoa, we're really hosed because we're starting to melt the ice caps and do all these like really dangerous changes.

So it's a much larger magnitude that we're talking about before we push it to a Venus-like state.

So we don't have to go there to get ourselves into trouble.

But nonetheless, it's an interesting question because if we do that, by the way, we are dooming all life on Earth and we are, you know, like it's easy to say, we're not gonna harm the Earth.

We're just harming ourselves.

But if you go to that extreme, then actually we're screwing the whole biosphere, not just human life.

Wow, it sounds like the plot of a future X-Men movie.

Yeah, exactly, exactly.

I've got a great question here from Tommy Mainz from St.

Charles, Minnesota.

And Tommy wants to know, what did the Russians do on their trip to Venus during the space race days?

Well, so the Russians actually had a lot of trips to Venus during the space race days.

They were very, very successful at Venus.

Really?

It was actually-

Are there bars of them?

I'm picturing like vodka.

Yeah, yeah.

Cast around liberally.

Exactly, no, it's kind of strange.

If you look at the history of the space race, we Americans were really successful at Mars and had a lot of trouble getting things.

Ultimately, we were successful at Venus, but we were more successful at Mars.

The Russians couldn't land a spacecraft on Mars to save their life.

They couldn't explore Mars their way out of a paper bag.

I mean, they threw all these spacecraft at Mars and they all failed.

It's actually very sad, the amount of resources the Russians put into Mars.

But for Venus, they were really successful.

They had orbiters, they had incredible landers.

The first landers on Venus were done by the Russians and all those pictures you've seen about, pictures of these strange landscapes with rocks and going off to the horizon of this eerie world.

The first pictures we got anywhere from the surface of another planet were done by the Russians with these really successful and incredibly well-engineered landers at Venus.

So the Russians have an amazing history of success on Venus, much more so than we did in the early days of the space race.

Wow, I know this isn't the question, but you've really now put it on my mind.

Like, why?

Why were they so good at Venus and not Mars?

What's that, is there, is it any one thing or is there?

Well, it's a great question.

And, you know, I think some historians have wondered about this, those Venera spacecraft that were so successful at Venus, in a way, it's similar to the Russian Soyuz capsules.

Yes.

That have been so successful with human exploration, you know, just a tough design that they perfected and basically just repeated over and over again.

And so the Russians, their approach to engineering, they did a great job solving certain kinds of space engineering problems.

And Venus was certainly a place where they were really, really successful.

Brute force, not elegant designs, but lots of money, big spacecraft.

Let's just keep throwing these massive, they were basically these big diving bells, not sophisticated spacecraft, but tough and dogged.

Let's just keep doing the same thing over and over again until we succeed.

And that approach, that Soviet approach, if you will, worked well at Venus.

And ultimately, they were very successful.

Wow, awesome.

It sounds great for Venus, not necessarily for dating.

Anyways, we, I think, need to take a break now.

I think we do.

But we will be back in a few minutes with more StarTalk Radio.

Bye Welcome back to StarTalk Radio.

I'm David Grinspoon, sitting in for Neil Tyson.

I'm joined here by Leighann Lord.

And we're talking all things Venus.

Yes, we are.

This is like one of the most fun cosmic queries that I've done.

This is cool.

I got a question from Mike Quijano, which is sort of what we've talked about a little, but goes a little bit further, because I wanted to ask this myself.

So Mike and I are on the same page.

If we could introduce something into the atmosphere of Venus, dissipate that dense atmosphere that you were talking about and reverse the greenhouse gas effect, could it be sustained unaided, or would it go back to the naturally high heat and dense doomed wasteland we've all come to know and love?

Good question.

It's tricky to sort of terraform Venus in a way that it could take care of itself, because the problem is there's still that intense solar input, twice the solar input from the earth, basically.

And so you would have to have something that's cutting that down, either some layer of dust in the atmosphere or some engineering solution, something in orbit blocking part of the sunlight.

I think it's tricky, unless if you go for the genetic engineering biological solution, one could imagine you have some organisms who are making use of all that solar energy, powering themselves that way.

And part of what they do, part of how they live involves removing CO2 very aggressively from the atmosphere and keeping things cool.

So I'm not gonna say no impossible.

I'm gonna say it's a tough engineering problem and it doesn't seem obvious to me how one would do that, but it's a problem for the future.

It's not something we're even trying to do or should try to do now.

I got a question here from Marco Horvat and a simple question may not be a simple answer, so who knows?

Why does Venus rotate so slowly?

Why is she taking her time?

Yeah, Venus has an odd rotation rate.

It rotates, not only does it rotate really slowly, but it rotates backwards from the direction of all the other planets.

Yes.

So on Venus, if you were on Venus and could see the sun, it would rise in the west and set in the east, opposite from Earth, because it spins around the other way and it spins around really slowly.

Now, the question is, why does it do that?

In fact, it spins so slowly that the day on Venus is longer than the year, which is kind of weird too.

It's a Venus year goes by quicker than a Venus day.

So it circles the sun faster than it spins on its own axis?

Exactly.

Did I just say that right?

You said that right.

And it spins backwards.

So the answer is most simply expressed in three words, we don't know.

But of course, being scientists, we're not satisfied with that.

We have theories.

And it probably has something to do with the formation of Venus.

You know, the spins of all the planets are set largely when they're formed by accretion, by the collision of smaller planetesimals, pieces of planets that come together and smash together.

That's how the earth formed and that's how earth and the moon formed and got their rotation.

That's how Mars got its rotation.

And Venus probably got its weird rotation by just the randomness of what collided with what and what orientation they were at to leave it spinning in the way that it is.

But the plot thickens somewhat with the thickened atmosphere of Venus that over time that atmosphere can absorb momentum from the planet and exchange momentum.

And you can even have things like solar tides where the sun pulling around that atmosphere over time is pulling on the solid planet.

And you may have tides that over billions of years changed the rotation rate of Venus.

So there's some people that think that maybe that slow rotation of Venus was not primordial.

That is wasn't left over from the origin of things, but evolved over billions of years due to the effect of that thick atmosphere sort of pulling tidally on the planet.

So, you know, again, I'm gonna go back to that initial three word answer we don't, or four, we don't really know.

I love that.

I really do love that.

Or you could just say Venus is dyslexic.

Venus is weird.

Venus is weird, but we love her anyway.

There's a lot of mystery about her, but yeah, we love her anyway.

She is the goddess of love after all in beauty.

Okay, we have time for one more quick question before the break.

So Leighann, what do you got for me?

I have a question from United States Air Force veteran Mark Esperanza and wants to know since Venus's day is longer than the year, how does it affect any storms and erosion in the planet compared to our planet, which has been so much more rapidly?

Good question.

The fact that Venus is a slow rotator compared to Earth, a very slow rotator does affect the weather patterns.

On Earth, you look at a satellite image from space or you look at a weather map and you see all these spinning storm systems, cyclones and just every kind of storm, all the weather is these spinning systems.

And that actually has to do with the rotation of the Earth and the kind of forces that it introduces.

Venus, without those spinning forces, has very quiet weather at the surface and very slow wind speeds and almost no erosion that comes from storms.

So, excellent question.

It is related to the fact that it rotates so slowly.

And now, I think we're going to take another break and we'll be back in a few minutes with more StarTalk Radio.

Now it's time for the lightning round, where we answer the questions that we didn't have time to get to in the non-lightning round, and we do them with lightning speed and quickness and hopefully cleverness too.

Well, let's not ask for too much, but let's go, let's hear some lightning questions about Venus.

All right, Brian Rudd wants to know if we directed a large enough asteroid towards Venus, would it speed up the rotation?

If we directed a large enough asteroid, yeah.

I mean, any asteroid's gonna affect the rotation, and most of them will be trivial, but imagine something like the moon forming impact that set Earth on an entirely new course and formed the moon.

If you had a large enough impact, sure, it would drastically alter the rotation of Venus, but it would have to be pretty large to have that kind of effect.

All righty, next question from Stephen D at Stephen Eman.

From Dublin, Ireland wants to know, necessary for any exploration of Venus in layman's terms, how do heat shields work?

Heat shields work partly through the obvious of just being something big that blocks out the air and keeps whatever behind it is cold, but there's also a more subtle factor called ablation, where you actually have materials that are designed to burn off, purposefully they burn off, and as they burn off, those reactions absorb a lot of heat.

So the actual chemistry of the material is such that as it burns off, it helps keep what's behind it cool.

Nicely done, sir.

Next question from Brad Mund wants to know, what would the average astronaut's spacesuit need to survive a nice stroll on the surface of Venus?

Man, surviving on Venus is not an easy engineering problem for a spacesuit engineer.

Because of that heat, it would need a lot of air conditioning, but it's also, we haven't mentioned this before, it's not only hot, but the pressure is really high.

It's 90 times the surface pressure of Earth.

It's crushing pressure and searing heat.

So it would have to be a tough spacesuit that could not be crushed in that pressure, and it would have to have a really, really good cooling system.

Not an easy thing to design, but human beings are clever and crazy, so I think at some point we will go to Venus and we'll need to design some pretty good suits.

Fantastic.

The next question is from Lakup Jarson.

Love the letter switch, dude.

I've been told Venus doesn't have tectonic plates.

If so, what does it have and how does it work?

That's a really good question because as we mentioned, Venus is basically the same size as Earth, so you would think that it would have some similar mechanism for getting rid of its internal heat.

Ultimately plate tectonics, which is Earth being divided into all these surface plates that are sliding around causing earthquakes, volcanoes, et cetera, is the way that Earth gets rid of its internal heat.

It's a mechanism for removing internal heat.

Venus, you would expect, has as much internal heat, so why doesn't it have plate tectonics?

And we're not completely sure, but it probably has to do with Venus being so dry, and you need a certain amount of water in the rocks to have things sort of squish around the way that plate tectonics do.

So Venus may be sort of seized up.

In that case, it probably loses its heat through volcanoes.

What's so funny?

No, I'm just having this image of Venus being constipated.

Well, it is.

Venus, I think constipation is not a bad metaphor.

It used to probably have something like plate tectonics, we think maybe in the deep past, but it got all dried out and couldn't move anymore.

And so now it probably loses its heat through a lot of volcanoes, basically.

Moving on, next question from Gabriel Finelli in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

What would be necessary if we wanted to send a rover-like curiosity to search for habitable environments that might have existed on Venus?

People have talked about designing rovers for Venus.

And at some point, we probably will want to do that because the Russians had a couple of landers.

We're trying to design more landers.

It's not an easy thing to land, even just to land on Venus because of that great heat and pressure.

But eventually, you want to not do more than just land.

You want to have mobility.

That's what's been so great on Mars.

Mars is easier, as tricky as it is to explore Mars, because the surface conditions aren't as intense.

It's actually a lot easier as an engineering problem.

So a lot of the problems on Venus would be the same as the ones on Mars as far as mobility and communications and so forth.

But you've also got to deal with designing machines that can work in those temperatures.

And so probably the electronics and all the critical components would have to be encased in some sort of structure that would be kept cool, maybe through a nuclear reactor, maybe through some other clever means.

But that's the basic thing is you either have to keep it cool enough so the electronics don't just fry, or you have to build a whole new kind of electronics that can operate in those temperatures.

It's a tough engineering problem, but we do have people at NASA and other agencies that are working on solving that.

And sooner or later, we will send a rover to Venus.

Nice.

Next question is from Sean Lee.

Will we ever be able to get high-res images of the surface of Venus?

That's tricky as far as, it depends what you mean by images.

If we're talking about radar images, which is we had a spacecraft called Magellan that orbited Venus in the 90s and took images using, you can't see the surface with visible light, but you can with radar.

So we can get higher res with radar.

If you're talking actual visible images, then we would have to do it with some kind of roving aircraft that was close to the surface and flying and not getting fried.

And the answer is yes.

Will we ever be able to do it?

Surely, but it's tricky because of the conditions there.

You either do it from orbit with radar, or if you want to use visible light, you have to do it from close to the surface, below the clouds and sort of travel over the whole surface and do aerial photography.

So it'll take a while, but we'll do it.

Do you have time for another question?

All right.

Unfortunately, I think we're going to have to wrap this up.

So I want to thank you all so much for listening.

I'm David Grinspoon filling in for Neil Tyson.

You can follow me on Twitter, at Dr.

FunkySpoon.

And I'd like to thank my co-host, Leighann Lord.

Thank you, Leighann.

Thank you.

And you can follow Leighann on Twitter, at Leighann Lord.

And we'll be back in a few minutes with more StarTalk Radio.

You've been listening to one of our classic episodes, originally recorded for season five of the podcast.

I'm Dr.

FunkySpoon, AKA David Grinspoon, an astrobiologist, and I'm back now to give you all a Venusian update.

I'm calling into the studio from my home, and we've got Chuck Nice joining us today.

Hi, Chuck, how are you?

I'm great, how are you?

I'm doing all right, thanks for asking.

Excellent, man.

I'm glad we're gonna talk about Venus.

I know that it's one of the things that you're very involved with, looking at the climate of Venus and comparing it to Earth, and that tells us, what exactly does that tell us?

I was about to tell us what it tells us, but I'm like, why am I gonna tell us when I don't know what the hell I'm talking about?

I should let Dr.

FunkySpoon tell us, because he knows.

Venus is kind of like holding a warped mirror up to Earth.

It's almost like looking at ourselves through a fun house mirror, because it's like an altar Earth.

It's a planet that should be like Earth.

It's so nearby, so similar in size, and yet it's gone down this very different path.

It's our, some people have called it our evil twin.

It's hot, it's acidic, it's probably lifeless, and yet it's so nearby, and it's just very strange that it's evolved in such a different path than our home planet.

I like it, Earth.

It's Venus, it's the Earth you want to party with.

Yeah, it's evil, evil twin Earth.

I'm evil twin Earth.

You can't take it home to mother.

Exactly, acidic and hot, yeah.

That's exactly how I like my women, acidic and hot.

I don't know if you would like Venus, but I don't know, maybe you should get to know Venus and then let us know.

Exactly, yeah, I might want to spend a little time with the first, so now here's the thing.

I know, I found out from you, because I really, I didn't know this was a real thing.

I had heard that there was going to be a mission to Venus or that they want to make a mission to Venus, but tell me about that, because I'm not sure.

Is there a mission to Venus or is it just that we want to go to Venus?

Because right now Mars is like everybody's Mars crazy, Mars.

So is there actually a mission to Venus?

Yeah, I mean, I think you're right.

Compared to Mars, Venus has been a little bit neglected, both in our scientific plans and in the public discussion.

Now, I've got nothing against Mars.

I love Mars.

I'm fascinated by Mars.

I'm so psyched about our missions there.

But I do think it's a problem that we haven't explored Venus as much as we should, because there's a lot we can learn from the comparison.

And honestly, the United States has been slacking in the Venus department.

We haven't had a mission there, a dedicated Venus mission since Magellan in the 1990s.

But fortunately, other nations have been stepping up.

There was the Venus Express mission, which the European Space Agency flew in, launched in 2005, got there in 2006, and lasted until last year, 2015.

It was a great orbiter mission and taught us a lot about the atmosphere, the climate, even a little bit about the surface.

And now there's a new mission by the Japanese Space Agency called Akatsuki.

It means dawn, which is great because Venus is the morning star, the dawn star.

And this mission, this Akatsuki mission, this Japanese mission has had an amazing story, actually, that most people don't know, but they should.

It's crazy, they launched it in 2010.

It got to Venus, made it fine across interplanetary space.

And then in the 12 minutes when it was supposed to fire this rocket to go into Venus orbit, something went wrong.

The rocket malfunctioned, it actually kind of blew up.

And the poor little spacecraft did not go into Venus orbit.

It went spinning helplessly in an orbit around the sun.

And that was it, we thought.

But it turned out it was on just the right orbit around the sun to bring it back to Venus exactly five years later.

It was sort of almost miraculous.

That's awesome.

And exactly five years after it was supposed to go into orbit, which made it December 2015, just this last December, they were able to make another try.

And even though that main engine was destroyed permanently, they very cleverly used the little maneuvering thrusters, which were not designed for this.

They fired them for 20 minutes all in the same direction, which was again, not what they were designed for, way beyond the design specs.

And it worked, they got it into orbit.

So now the Japanese have this Akatsuki orbiter in orbit around Venus and it's just starting to do science.

So we, the United States don't have a Venus mission right now, but we humanity do.

And so Akatsuki is just starting to do its thing and tell us some cool new science about Venus.

Well, let me just say congratulations to the Japanese space program.

And for them, sciencing the shit out of that.

I mean, you know what's so funny is that that is a theme in so many space movies where you have to use secondary or tertiary rockets that are a part of a vehicle or a part of a craft for purposes they were not designed for.

Even in Star Trek, they will, when they lose warp engines, they will often find a way to use the impulse engines in such a manner that they weren't designed for.

Yeah, that's exactly what this was like.

It was like, Captain, the warp drives out.

We're going to have to try it with impulse.

Right, exactly, yeah.

And the Japanese are very good at that.

They've done that with a couple other missions.

It seemed like they were dead, and then they found some clever solution and resurrected them.

So it's just thrilling that we now have a mission at Venus.

Meanwhile, there are actually a couple of American missions which are proposed and on the books and may get to fly to Venus.

Oh, great.

There's a class of missions we call discovery missions, which are the sort of small-scale NASA planetary missions.

Small-scale meaning they cost less than a billion dollars.

And there was a recent competition and there were five missions selected to sort of go to the finals, which is what we call phase A, which means that each team gets like a million bucks to develop the concept further.

And then a year later, NASA picks one or maybe two to actually fly.

And in this recent round of mission competition, there were two Venus missions.

So two out of the five that NASA is now considering for their next mission are Venus missions, which is great.

We've never made it that far with a Venus mission in this competition.

So those of us in the Venus science community were very hopeful that one or who knows, maybe even both of these missions might get to fly to Venus.

One of them's an orbiter and one of them's an entry probe that would fly down in the atmosphere and take data all the way down to the surface.

And they'd both be really cool.

So we're working really hard on these proposals and keeping our fingers crossed.

And it may be that later this year NASA will announce that one of these is actually selected and that we will have a new American Venus mission.

And so why is it, now why is it, David, that, you know, I hear you guys, you know, doctors like yourself and, you know, Carolyn Porco and I hear, you know, the people that we work with here at StarTalk from NASA.

And it seems that when I hear these wonderful things that everyone's proposing and wants to do, what I don't understand is why is it that we can't do them all?

It seems like you have, like, we're gonna have to pick one or the other, we might get funding for this or that.

Why is it that with all the money that we have as a nation, you can't, why do you have to pick one fricking, like, we're not a family going on vacation, you know what I mean?

All right, kids, it's either Wildwood or Great Adventure.

That's it, like, we don't have the money to go to both.

You get one or the other.

What the F is going on that we can't land an orbiter, that we can't have an orbiter and a lander on Venus, and that we can't also have a mission to retrieve, you know, samples from Mars at the same time?

What is that?

Well, I mean, it's, you know, like the song goes, it's money, honey.

That's what it is.

I mean, you know, yeah, we're a rich nation, but we, you know, it's always a battle for priorities.

And, you know, if it were up to me, you know, the amazing thing is we could double the NASA budget.

It would still be a tiny piece of the national budget.

I mean, really tiny piece.

And we could do all these missions.

So, you know, if I were running things, I mean, I feel like it's very important, not just because I'm curious about these places, which I am, but because I think the knowledge, the knowledge we get is very crucial and useful for us, knowing how to manage our own planet and just, you know, understanding our origins and who we are and what the heck we're doing here on this planet.

I think it's really important.

If it were up to me, we would do all of them, but, you know, we're given the budget we're given and we have to choose and, you know, so there's a competition and it is frustrating because honestly, these five missions I mentioned, they're all great missions.

You know, one of them is to go to a new kind of asteroid, an iron, a metallic asteroid and check it out.

That would be so cool.

One of them is to go to the Jupiter Trojan asteroids, which are these asteroids that follow Jupiter in its orbit, 60 degrees behind its orbit, where we've never visited those.

Two of them are Venus missions.

You know, they're all great missions and none of them are bad.

Anything that's made it that far in the competition, it's worthwhile.

But it's just a matter of limited resources.

And so therefore, we're forced into this brutal competition to try to convince NASA that our mission is the best.

I don't get it.

It's like science survivor.

You know what I mean?

It's like you've taken these things that all of them should be done and you put the scientists against one another and you say, all right, now tell us why you should.

It's like that show on, I forget the name of that show on CNBC where the guys come in and they pitch an idea to these business people and they say-

Yeah, yeah, it's Scientific Shark Tank.

That's the show.

It's Scientific Shark Tank.

What the, what, that's not, come on, man.

That's not cool.

Scientific Shark Tank, come on.

You know, I hate to say it.

It is kind of like that.

I hate to say it.

But you know, there's a brutal aspect to it.

Yeah, that's not cool, man.

Scientific Thunderdome, two scientists enter, one scientist leads with some money to do something maybe good.

So that's cool.

Well, I mean, the good thing is the ones that lose the competition, they don't actually get killed.

We don't have to put to death.

But we don't get to fly our mission, so it's almost as bad.

At least we have that, right?

Oh man, these conversations, these little, it's so great when I talk to you, you know, cause you're on the cutting edge.

You know, we're talking about Venus, we're talking about Mars, we're, you know, astrobiology, all these things.

You're so, you know, you're so out there on the edge of scientific discovery and I just love talking to you, man.

Thanks so much.

Well, thank you, Chuck.

It's always a pleasure to talk to you about anything, really.

And this has been really fun.

I guess this means we're out of time.

So this has been StarTalk.

Thank you all so much for listening and we'll be talking to you soon.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron