About This Episode

Brilliant scientific discoveries and cutting edge technology have transformed our world, yet many people are turned off by science. Where has the excitement for science gone, and how can we get it back? Stephen Colbert developed an interest in science at a young age, and now he shares that fascination by inviting scientists to appear on his show The Colbert Report.

NOTE: All-Access subscribers can listen to this entire episode commercial-free here: Exciting Times for Science.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTOur universe is filled with secrets and mysteries, leaving us with many questions to be answered. Now, more than ever, we find ourselves searching for those answers as the very fabric of space, science and society are converging. As we...

Our universe is filled with secrets and mysteries, leaving us with many questions to be answered.

Now, more than ever, we find ourselves searching for those answers as the very fabric of space, science and society are converging.

As we give you the knowledge that breaks the barrier, between what is science and what is merely pop culture, this is StarTalk.

Now, here's your hosts, astrophysicist, Dr.

Neil deGrasse Tyson, and comedian, Lynn Copleth.

StarTalk.

Welcome back to StarTalk.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, astrophysicist, with my co-host, comedian, actress, Lynn Copleth.

Lynn.

Welcome back.

We missed you last week.

I missed you guys.

I was in Pittsburgh.

I had to find a co-host.

I don't know if that was even possible, but we found one of my colleagues.

I heard he was very, very funny.

Yeah, he's a great guy.

He's from Kentucky.

He's a Kentucky astrophysicist.

Another astrophysicist.

We're out there.

You just got him falling out of your bum.

You cannot escape us.

We are everywhere.

You're listening to StarTalk.

Our toll-free number is 1-877-5, StarTalk.

We'll be with you for the next hour.

Lynn, today's subject is really just about science and trying to get people excited about it because that's something that hasn't been the case all along.

Well, Neil, I mean, I'm warming up to science.

I have to tell you, now that I'm working with you and you're making it much more approachable for me, but you're not the warmest group of people, scientists.

Well, what we try to do is at least try to find sort of benchmarks of occasions to remind people of the value of science.

Right now, it's like the 40th anniversary of the Hubble landing, and science does make the news.

And so, but I agree, we're not always warm, but...

No, not only not warm, you're also kind of boring sometimes.

I mean, honestly, there are two kinds...

Remember science teachers when you were in school?

There were two kinds of science teachers.

There was you, the science teacher that was exciting, and you were making volcanoes and doing all sorts of cool stuff, and you know, and then there was a Buehler, Buehler, that kind of science teacher.

I remember him from Ferris Buehler's...

Buehler.

That was like the science teacher, like the guy who stood and did the Pythagorean theorem for an hour, and you were like, who is this?

So what you're saying is science, you're realizing the scientist might, that science itself might be intrinsically interesting, but the people who delivered it to you were not, and therefore left you in the cold.

That's what you're saying.

Yeah, and now I actually watched Nova the other time.

When there was a real, the other day when there was a Real Housewives Marathon on.

Do you know how amazing that is?

That is not normal for me to do that.

Well, is that because you've changed or because our delivery products have changed?

No, because I've changed because you are making science more approachable and interesting to me.

Most of the time, it's not, and not to be mean, but when I'm at your office sometimes, some of your colleagues come by.

Mm-hmm, they do.

And with their spock ears and their weirdness.

Well, they don't always wear their spock ears.

No, but I can see it.

I can see past their normal...

You see the tan line around where the spock ear goes.

Yeah, and my point is that scientists speak in a jargon sometimes that's not approachable and almost elitist.

Well, but to each other, what else can you expect?

No, they do it to regular people like me.

It's like going to France.

Have you ever been to France?

I went to France and I would try to understand them like, Marcia Belsky, no, that's what I see.

You're saying it wrong.

And it's like, okay, you know what, how about I leave and I take my tourist money with me, you freak.

That's what I'm saying.

And it bothers me because I feel like my nieces...

So the scientists are like the French.

The scientists are like, yeah, and I don't think that they're being...

I just think science needs some sort of makeover and a publicist.

Interesting.

Interesting.

So you think the entire enterprise of science could benefit from like a marketing agency that worked with it at every turn?

No, because I'm saying like I'm watching Nova the other day and Nova is not a terribly sexy show.

I mean, when you're on it, it is, but my point is...

Well, that's so nice of you.

But my point is that it usually...

It's no discovery show.

It's no like...

There's no deadliest catch.

There's no ghost hunter.

So you need to think...

It's like facts.

Okay, but here's the problem.

Scientists are not trained to be storytellers.

We're not trained to be funny.

We're not trained to be any of those things.

We're trained to be inquisitive on the frontier of our understanding of the cosmos.

That's all we're trying to do.

So there are others that try to help us out.

There are journalists occasionally do this.

There are science writers.

We can't do it all.

I think that's...

Well, you know what?

If you want the public to give you money so you can do your little experiments, then you need to be approachable and you need to be able to speak so that we can understand you.

I wish I could argue against that.

I can't.

I'm just saying that we're not trained for that.

Now, fortunately, we have some journalists who are very nice to scientists.

One of whom is Stephen Colbert.

You know, I've been on a show six times.

Six times.

You have?

And I've been on it none.

Well, I don't get big headed about it because I know he's actually had other scientists on.

And so in my last appearance, I actually snared him for a few minutes afterwards and I interviewed him about his interest in science.

I'm interested in hearing this.

Yeah, let's check out.

Let's check out a first clip of me interviewing Stephen Colbert on StarTalk Radio.

Check it out.

Right now, I'm with Stephen Colbert in his office.

And I think he's out of character at the moment.

We'll find out.

We'll find out.

Let's see how I feel about science.

If I give it any credence at all, you know I'm not in character.

So Stephen, as of today, I've been on your show six times.

Now, I might otherwise get a big head about that, but I've seen other scientists on your show often.

So I'm led to think that you actually have a soft spot for science.

Am I delusional there or what?

I love science.

My dad was an immunologist.

And I am thrilled by science.

When I was a kid, education was valued in my house, and because I was the son of an academic and someone who was a medical researcher, science was number one.

Though we're also a very devout family, too.

Like, my mother is sort of mystical Catholic.

My father is sort of intellectual Augustinian, or, you know, like, Aquine Catholic.

But you understood the value of science in your life and in society.

Absolutely.

I mean, yes, absolutely.

My father, no fan of herbal medicine.

No, repeatable results, repeatable results.

That was the mantra.

So are you a science geek or just a science enthusiast?

I'm a complete geek, but I wouldn't, I wouldn't, I wouldn't give myself the honor of calling myself a science geek because I think you have to have more knowledge of science.

I have appreciation for science.

I really, I love hearing scientists talk.

I love, I love, I love new discoveries.

I love people who are full of questions at all times.

I think you've transformed the landscape of comedic talk shows, or talk shows at all, the fact that you recognize scientists as having a role in the dialogue of how, what drives the nation.

Well, science is hard, let me put it that way, unless you approach it, I think, from what I know, unless you approach it with joy and fascination and drive, and all of those things hint to me that the things that scientists are trying to explain to us must be pretty interesting.

And so I take them at their word, and I have them on to try to explicate that, open the rosebud of their knowledge or their desire in front of us so that we can see the beauty of the rose ourselves, if you know what I mean.

That's beautiful.

Thank you.

Very beautiful mind.

What a beautiful mind.

So I don't want to put you on the spot asking you to pick your favorite children, but among all of the frontiers of science, which branch of science excites you most?

It's astrophysics, Neil.

Stop fishing.

It's astrophysics.

It kind of is astrophysics.

It kind of is astrophysics because it asks such enormous questions.

So you're not just saying that because I'm sitting here right next to you.

Of course I am, but I also mean it.

You know, I love first questions.

Why are we here?

Or rather, how are we here?

And then you can obviously interpret your why, but the how are we here question is enormous and fills us with awe.

And that is certainly a cosmologist and natural physicist approach those things.

And that's what we do.

We live that.

It's a high calling.

Stephen Colbert, he's a cool dude.

See, you need more Stephen Colbert in the science world.

You really do because he's sexy and he's charming, but he was raised by a scientist, so he speaks your language.

That's my whole point.

Science needs a makeover.

You need queer eye for the science guy.

Well, he also made a good point that he recognizes that there are these deep fundamental questions out there that we all have.

You know, when I sit out under the stars, I am not alone.

Well, I'm not alone in my thoughts when I sit out under the stars.

You're totally alone.

What do you say?

Where did I come from?

Where does it all begin?

Where is it going?

But science is more than just the deep questions.

It's also practical things like cell phones and the Internet.

Well, what he said, excuse me, what he said that really touched me, again, as someone who's not a science person, so to speak, is repeatable results.

I think that's a very interesting thing to say to a little kid.

You know, because I think a lot of people do look up and wonder where, you know, I think even small children, my nieces ask those questions, but they're not given many different answers.

They're given like a Christian response or not, well, you could be here because of this or you could be here because of that.

Well, okay, so but what happens when they become adults?

Because I know that when you're a kid, everybody's curious, and the recent survey asked adults, could they name some major scientific advances and people could hardly do it?

Lynn, can you name three scientific, three major scientific advances?

Yes, I can.

Well, all right, go for it.

I'm counting.

How about the atom bomb?

Well, I think of E equals MC squared, which led to the atom bomb.

Okay, see, that's what I'm talking about, about talking.

Neil, Neil, seriously?

What?

I'm not kidding.

People listening, call in if you think that Neil is talking to the...

What?

Okay.

E equals MC...

I just want to say that, yes, scientists invented the atom bomb, but the science of the atom bomb came many, many years, a whole generation before the atom bomb.

I just wanted to make that clear.

Well, then make it clear.

Don't be a snooty, snooty, snoot by telling me, oh, when you say atom bomb, I think E equals MC squared.

That's like going to the gym and I'm doing weights and you walk over to me and go, you know, you really should do more weights.

You know what?

I'm not doing anything now.

That was Lynn Coplitz on StarTalk.

Am I in trouble because I said that curse word?

18775 StarTalk.

So, Lynn, that was one.

That was one.

Give me another.

I'm sorry.

I bring it down to a really basic, too basic level.

Okay, another DNA.

DNA.

Good, good.

That was mid-century, mid-20th century DNA understanding.

Huge, huge.

Nobel Prize and everything.

I mean, people are being, like, all co-case files and things are being...

Remember, all my knowledge of anything is from television.

We must remember that.

And DNA, some would say it got out of hand.

I just recently read that there's a company, RNL Bio, that will clone your pet for 150 grand.

You have a dog, I think, right?

What do you own?

I do have a Yorkie.

You have a Yorkie?

Would you fork up 150 grand?

And he bites me whenever I leave and he barks.

He's abusive.

I feel like my name is Luca.

But people worry about this gone awry, just our understanding of our genetic identity.

If they clone him, will he be the same dog?

No, he won't have the same life experience, but he'll be genetically identical.

But his behavior might still be modified.

So he could be evil.

He would be genetically identical.

And to the extent that genes affect behavior, that would show up in his genes.

Can you do that to a baby?

Can you have your baby cloned?

I don't see why not.

There's nothing stopping that from being in our future.

So DNA is a big one.

Give me another one.

Wait, one more question.

That movie Gattaca, could you make your baby the way you wanted it?

Like you wanted a blue-eyed baby?

Gattaca was different.

I remember Gattaca.

They weren't creating any baby they wanted.

They looked at all of the genetic variation within the couple, and they picked from that variation the baby that they wanted.

And then they got rid of the ones that had...

If you had asthma, you were like a janitor.

Yeah, no asthma.

Remember that you were like a janitor?

Oh, yeah.

That was a spooky movie.

I remember that.

Low-budget sci-fi horror movie.

What I didn't like about that is what's wrong with being a janitor?

It's not really an awful...

That's a good job, man.

No, janitor is cool.

Yeah, people leave you alone.

You do your own thing.

How about vaccines?

Vaccines are a good one.

That's a good one.

A whole lot of people alive today that would have been dead at any other generation were not for vaccines.

And this is what I'm talking about.

And my sister gets upset when I talk to my nieces like this.

But this is the kind of thing where I'm like, you know, that flu you have, if this was like a hundred years ago, you could have died from that.

Yeah, that's right.

My sister's like, don't tell them that.

I'm like, why?

They should know what science plays in their life.

They should know that penicillin was found on moldy bread.

Yeah, oh yeah, science.

I mean, there could be some weevil in my, you know, rice right now that could save, you know, be the cure for some strand of cancer.

And that's why the frontier of science always looks scary to people, but down the line, people always find ways to bring it back home and bring it into your living room.

It's not only that, you know, with DNA and genetic modifications of food, the whole, the French, getting back to the French.

That's your imitation of every French person.

Don't talk about Indian.

I'm French.

You know what they call genetically modified food?

They call them Franken food.

What they don't know is most of the produce...

What is genetically modified food?

I don't even know what that is.

Well, sort of any food that is not drawn from nature.

Oh, like square tomatoes?

I love that stuff.

Fine, yeah, but they don't.

They want to go back to nature.

What they don't understand is that there's a lot of stuff in nature that will kill you.

There's a lot of stuff in nature that is not good for you and make you sick, and this stuff protects the food.

I mean, it's science in the service of human interest.

I'm so glad you said that, because I have a girlfriend that always goes to holistic places for medicines, and I said to her one day, I'm like, you know what, you got to be careful what you mix with stuff, because hemlock and white oleander are natural.

Natural, and they'll kill you.

Oh, yeah, everything natural is not good.

Isn't that the truth?

That's why I get Botox.

Now, here's what's interesting.

And that is good.

Is that why your face hasn't budged all day today?

Yeah, I got it my birthday next week, so I had to get it in time for it to kick in.

Lynn, we got to get back to this.

Thanks, Neil.

You're listening to StarTalk.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

And you've just been hearing Lynn Coplet's comment on her recent Botox.

This is StarTalk.

Give us a call at 1-877-5.

We'll take a break and be right back.

We're back.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, with my co-host, Lynn Coplet.

You're listening to StarTalk.

Give us a call at 1-877-5-STAR-TALK.

If you have a comment about what science has meant in your life, is it...

Or what excites you?

Or what excites you?

Is it making you suffer?

Is it making you...

giving you dates?

What is it doing for you?

What science breakthroughs do you...

do you appreciate?

So, Lynn, let me just ask you, the science...

A lot of people don't like science because they're afraid that it's going to bring an end to the world, and they're campaigning against it, and...

Really?

Is that really true?

Yes!

People don't like science.

Yes, yes.

They say science is bad, and they want to go back to nature, and I've...

you know, and so there may be some...

No, I understand.

I think there might be...

no, I think there might be scientists that might regret some of the things that they've discovered, don't you think?

I mean, I think...

That's an excellent point.

I wonder.

I wonder that.

Like the atom bomb lady?

Okay, at least might know.

Yeah, she was part of that whole sort of atom bomb community.

Yeah.

That's true.

Maybe some of them...

I just want to look back and be like, eh, that was not a good one.

I probably could have done something else.

Yeah.

Now, I'd like to draw a line in the sand between the science behind the bomb and the fact that a nation decided it wanted to build a bomb, because scientists don't wield resources, they don't wield budget.

The government wields budget.

So the scientists are splitting the atom...

Yeah, they're doing their job.

They're doing what they're told to do.

They're splitting the atom, exploring what the atom is doing.

And then someone says, hey, and scientists might have been among those, saying, hey, there's energy in here, we can tap it to kill people.

And so then a nation marshals resources to create the bomb.

So I can tell you that most scientists are not involved in any nefarious applications of their discoveries.

Most of them.

And so they're not really...

because it happens later by other people.

Okay, again, nefarious, what?

Oh, what is nefarious?

I forgot what nefarious means.

Did you really?

I love that!

I just stumped you with your big Mensa word, and you don't know what it means.

Mensa word.

I'm trying to get a good definite.

Nefarious would be for evil or non...

Oh, so for evil.

But here's...

well, the thing is, Neil, is what are you...

I don't understand what you're trying to say then.

You're saying that scientists, it's not their responsibility.

Because I think it's your responsibility to say no to something if you know that it's going to be used for bad.

Yes, and so you can speak up against it, the politics of it, right.

But the actual...

when you're on the frontier of discovery, you're not always thinking, oh, this would make a bomb.

No, you're saying, I can split the atom.

That's kind of cool.

And later on, you say, hey, they can make a bomb of this and you can campaign against it.

Einstein campaigned against the bomb.

And it was his equations that enabled it in the first place.

But here is my whole point that I'm making on the show today about getting excited about science.

And people listen, Colin, if you agree with me.

I am saying that the whole point is that people need to understand, you need to be able to talk to people so that they know what's going on.

If you don't do that, if you as a scientist don't make sure that American people know what you're saying.

Write your articles, communicate.

And I don't mean in your nefarious...

There are science fiction movies that take science to sort of evil, destructive, catastrophic limits.

Like Terminator, that was like the machines taking over.

And this has been going on from the beginning.

Go back to Frankenstein, the original story.

I know, Neil, that's my point.

Is that we, the people, who I'm speaking for right now, our information is misinformation.

Because it's Hollywood information, TV information.

You're talking to a woman who gets a lot of her stuff from TV.

But it can also stimulate it in another direction.

For example, remember I had an interview with Stephen Colbert for this show, and he commented on science fiction.

I'd like to know what he has to say.

Let's see what he has to say about what role that played in his life.

Science fiction was incredibly important to me.

When I was 10, I remember I had this tremendous headache one day, and I was over at my brother Ed's house.

I'm one of 11 kids, and he's the second oldest.

Eleven?

I'm one of 11 children, yes.

And there were certain sciences that my parents didn't practice.

And I was lying on his bed at his house, or in a guest bedroom at his house, trying to sleep off this headache.

And he was a huge science fiction fan, and he grew up in the 1950s and had all these great original pulp science fiction, and some from the 60s and 70s too.

And I picked one of the books off the shelf, because it was right about head level, and it was The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton by Larry Niven.

And I read it lying there after my headache was gone, and I was hooked.

I read nothing but science fiction, and at the same time, Cosmos came out by Carl Sagan, and...

So had you not gotten this headache, you might not have stared that book down to write it.

I never, no, no.

I would not have been captured by kind of like the romance of science, if I might talk about The Dragons of Eden by Sagan.

By Carl Sagan, yeah.

Yeah, yeah.

Meditations on the Romance of Science.

Isn't that what it's called?

That's the subtitle of it.

Yeah, yeah.

Dragons of Eden, Meditations on the Romance of Science, which I then...

Oh, no, no, no.

That one.

Oh, no, no.

That's Broke His Brain?

Broke His Brain, yes, yes.

Well, anyway, I read both of them.

I read a ton of things, including Cosmos and some of his fiction.

So I'm just playing into what is a preexisting ripe condition for you.

Oh, gosh, yes.

I mean, I love it.

I'm completely captivated.

I mean, before I knew you, I knew you because I knew of you because I'm a huge fan.

I'm a huge fan of the way you express science.

I showed your work to my kids.

And it's distressing that Americans don't know or care enough about science because when I was a child, science captivated young people because it was hot.

It was adventurous.

The adventure is what I think people don't feel today.

Maybe not.

I think it's because we were promised things like the wrist televisions and the jet packs, and they didn't come fast enough.

And the bubble cars.

Right, yeah, and the bubble cars.

All that, you know.

We were promised too much by the Hollywoodization of science.

See, now that's where I disagree with him.

We weren't promised too much.

When you promise a lot, you give people a lot of hope.

Yeah.

And we were promised a lot of cool things, and we have a lot of them.

I was promised as a kid, I would be able to talk to somebody via a viewer, that I could look at them on a telephone and be able to see them.

A video phone.

A video phone, that's what I'm supposed to do.

And now I can.

And I don't have a full robot yet, but I can have a little robot that vacuums my house.

The rumba robot.

And some of these other things, like flying cars.

We have monorails.

That's basically a flying car, but actual flying cars.

I mean, we don't have...

I bet we have the technology to make that, but we're not responsible enough to do it.

I don't think people should be allowed to have a flying car.

They're not doing well with street cars.

So, by the way, we have more Stephen Colbert to come later in the show.

And if you have a comment or a question, just come right on in to StarTalk.

You're listening to StarTalk Radio.

But, Lynn, fine, fine.

I even agree with you that a lot of the future we had imagined has come.

However, I think people imagine an even greater future than we currently have.

People thought we'd be living on Mars and be space traveling, going places, actually, rather than driving around the block, as we've been doing for 40 years.

And so, around the block is just orbit around the Earth.

So, I think some of it got over-promised, and that may have frustrated some people.

I'm just saying.

And what I want to know from you is, do you think that science, the delivery of science, needs action figures?

Or can people get excited just about the ideas?

No, I said I think science needs a makeover.

I think it needs to be sexy.

I think it needs to speak to the people.

The subjects or the people themselves?

That's what I'm trying to get at.

Everything.

Everything.

The people and the subjects.

Shows like Nova are shows that people should be watching.

More than something like Deadliest Catch.

I say that now.

I'll never be on the Discovery Channel.

But I really believe that.

Deadliest Catch, how many times can I, oh, look, they're going to try and catch the fish, and another one went over the side.

I mean, big deal.

But I'm watching Nova and I'm learning things about the planets and stuff that I really needed to know.

So here's what I'm saying is people like Al Gore and you, you know how much I learned from like an inconvenient truth?

It's good because he could speak directly to people.

The reason Barack Obama is our president is because he's a straight talker.

I'm sorry, but I understood him.

I could understand what he meant.

Bush got done talking, I still didn't know what the man was trying to say.

His own wife didn't understand what he was trying to say.

My point is that Barack Obama is a straight shooter.

When he speaks to me, it's a straight shooter, and we need more of that in science.

We need to be just spoken to like, here's what's going to happen.

Al Gore went out there and said, look, if you don't do this, this is what's going to happen, and this is why it's important.

All right, so it's one thing to be a straight shooter, but do you also need a hero?

I'm trying to understand the difference in the human emotion between being in love with an idea, a scientific idea.

You gave me your list of top things, atom bomb and DNA and vaccines.

You didn't list people there, I didn't ask you to list people, but you recognize those ideas as important.

And I'm just wondering whether people need the action adventure science hero to become scientists, or is the science idea enough?

The idea is enough.

People should call in and tell us what they think too.

But I think the idea is more than enough.

I just think that scientists, and you keep avoiding what I am asking you and what I am saying, scientists themselves, you and your colleagues, and you do your part.

Some of your colleagues don't.

I am saying it is your responsibility.

You do the research.

You need to share it.

Suppose you can do research, but you are no good at sharing it, and you try and then you fail.

Well, you need to take a speech class in between your astrophysicist class, is what I am saying.

That is exactly what I am saying.

I am saying it is my responsibility to learn science when I am in high school.

Then why don't science students take a speech class, a communication class?

I have a more realistic idea.

Did you know that in Hollywood and in the, what do they call them in Washington?

The National Academy of Sciences have gotten together in something called the Science-Entertainment Exchange, where in Hollywood, if you have a script line, you can, based on science, on a Rolodex are scientists who can help you get your science right.

Well, you should do that.

That is absolutely true.

Okay, so there's some effort.

There's some effort to make that happen.

We should have been doing that all along.

That's my whole point.

That's all along we should have been doing that.

Movies, like this stupid thing where Baschemi is sitting on the comet, drilling into it.

That shouldn't even be out there.

That can't happen.

I'm not a science person.

I'm watching it going, this is ridiculous.

Historically, scientists have not been part of the job to share their research with the public.

Oh my gosh, Neil, that is so not true.

That is so not true.

Because Galileo wrote in Italian rather than Latin in order to talk to people.

Am I not right?

Yes, you're right.

I stand corrected in his case.

My whole point, okay, let me boil down my point.

My point is, okay, fine, it bugs me that we spend, I am a Christian person who is very spiritual, but I ask myself what would Jesus do, but I think that we should also say what would Newton do.

I think my little dorky niece should know that Einstein was kind of dorky.

I think that's important, and I think when you start teaching kids stuff like that, they get excited about that, and children are our future.

And that's how you start.

You start by telling them, you know what, you doodle, we think that's weird and annoying, but Darwin doodled, and that's how he got the idea for evolution.

Didn't he draw beaks?

Oh, Darwin, yeah, he went to the Galapagos Island and studied finch beaks.

And he just kept doodling finch beaks.

That lit his fuse and...

Light a fuse, Neil.

That's what I'm saying.

Take a break on light a fuse.

You're listening to StarTalk.

We're going to take a break and more of our interview with Stephen Colbert.

Light a fuse.

We'll see you in a moment.

The future of space and the secrets of our planet revealed.

This is StarTalk.

We're back in StarTalk.

Neil deGrasse Tyson with you and my co-host Lynn Coplitz, professional comedian and actress Lynn.

Lynn, you called me out right before the break.

You're right, Galileo, one of the most famous scientists there ever was, took time out of his day to figure out how to talk to the masses and tell him what his ideas were that transformed the world.

And he wrote in Italian.

So you remember, we had that on a previous show.

Listen, you got rid of me and you lit a fuse.

You got me excited.

You made Galileo sexy.

You brought sexy back.

And I think there are other sexy characters back there.

I think Magellan was pretty cool for going around the world, you know, not knowing if he's going to make it or where he's going.

Sexy and courageous.

I mean, that's the thing.

You're talking to a kid, and I say we start with kids.

And you had a kid who needs to be courageous about something.

You say, look at Magellan.

Look at Christopher Columbus.

People were telling them not to do these things.

And people were saying, it's flat.

It's flat.

Don't go.

Everybody had somebody telling them not to do it.

The Wright brothers, Charles Lindbergh, everybody.

You know, people going to the bottom of the ocean, going up into space.

That is definitely the case.

But so we have the history of discoverers, adventurers, people with flames lit under them.

But how do we have future discoverers and adventurers if we don't excite them?

I'm just glad we got Bill Nye on our speed dial here.

Speaking of exciting.

Bill Nye, we missed him at the top of the hour.

We're going to bring him in right now for the nine minutes.

See what he says about the love of science.

Bill Nye, the science guy.

Hey, Bill Nye, the science guy here.

This week is the anniversary of landing on the moon.

Big, important, historic things.

But along with all you might hear about the moon right now, keep looking up and to the future.

We continue to explore Mars, so different and so much like our world.

Except for toddlers and babies, StarTalk listeners like you were alive when it was discovered that, oh, yes, there was a Big Bang.

But not only that, the bang is bigger than anyone suspected.

The universe isn't just expanding, it's accelerating.

Darwin and Wallace made their discoveries without even knowing what deoxyribonucleic acid DNA is, let alone what it does.

Now we can find the sequence of just about any organism you can shake a precisely buffered enzyme at.

These discoveries are part of what I like to call the PB&J, the passion, beauty and joy of science.

This is what StarTalk is for, to celebrate the human need to explore, to discover, to know, as best we can, our place in the universe, our place among the stars.

Well, here's hoping along with the moon this week, you think about the PB&J.

I get to fly, Bill Nye, the science god.

Oh, that Bill Nye.

I feel like anyone under 10 is like peanut butter and jelly.

And the Bill Nye is not only that, passion, beauty and joy.

I love that though, but that's, you know what, I really love that.

You'd think I would make fun of that, but I think that's pretty awesome what he just said, because that's what I am saying.

Okay, well, how about this?

So, one way to get people excited is to try to get scientists to get you sort of jazzed about it.

But they're entertainers, I think, can play their role as well.

In my time with Stephen Colbert, we chatted...

No, we did.

We chatted about...

He marshaled the Colbert Nation, his supporters, his fan base, to take action, to try to influence what NASA was going to do with their next voyage to the space station.

This is remarkable, that he would value it enough to then marshal his people, his peeps, to do this.

Yeah, and I want to hear about that, because that's my whole point, is that it is our responsibility once you know something and you have a voice, like we do right now, to make that voice known and to say to people, this is really important.

Well, let's go.

Let's check out, picking up on my interview with Stephen Colbert in his office.

You're listening to StarTalk, 1-877-5, StarTalk.

Here we go.

On my official bio for years, I wrote that my birthday was the date of the moon landing, just to see if anybody would ask me and see if somebody would catch what day I was using.

Which is, is it 24th?

That's a geek thing to do.

24th of July?

No, 20th of July.

20th of July?

Anyway, I put down 20th of July.

That's a geek thing to do.

Oh, I'm a total card carrying geek.

Card carrying geek.

I don't remember, I don't remember Apollo 11, even though my mother swears, I was, I guess I was five.

My mother swears that, no, you were up like every other child in the world, and you were in front of the TV, but I don't remember it.

My first remembrance of space was the 1970 eclipse.

That eclipse, yeah, there was a couple of big eclipses then.

And the 71, that's the, I think that's the Carly Simon eclipse.

Which one?

Oh, total eclipse of the sun.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Went to Nova Scotia, right, right.

That one went up to New England, but through the middle of, it would have gone up, right, it would have been where you lived, right.

Yes, I think my mother thought that when I stepped outside, my eyes would burst into flame inside my head.

I think I was allowed out for like a second or something like that.

I remember the launches.

I remember the president welcoming people back.

I ate space food sticks, you know, from Pillsbury, I think, or Carnation.

I forgot who made them.

And I had little moon modules.

I was thrilled.

I remember we were allowed the very first shuttle when the Enterprise came off the back of the...

The Enterprise was a non-orbiting shuttle.

It was just to test the aerodynamics of it.

Exactly.

And so NASA threw a bone to the Star Trek fans and called it Enterprise.

We were all impressed by how much you were able to mobilize the Colbert Nation to vote on your behalf for the Space Station.

And I looked up the numbers.

You had five times the number of votes than the next highest vote-getting name for the Space Station module.

So this is impressive.

It's a little scary, actually.

Well, all I can say is whatever the next one was, like Harmony or Cooperation or something like that, they need to get a legion of rabid fans.

They need a robot army to attack people like I have.

But did that response surprise you?

No, I'm not.

I have tremendous faith in the nation.

I was surprised in 2006 when we got 15 million votes for the bridge over the Danube in Hungary to be named after me.

When there are only 10 million people in Hungary, that surprised me a little bit.

But once we achieved that, I thought, I better be careful where I point this.

So it also means you have the power to affect change in society that others wouldn't.

So you could use the humanitarian aspect of yourself to do that one day, perhaps.

If my character weren't hideously selfish, that would work out.

But unfortunately, everything is just related to...

He's the most insecure person.

Let me show what I just got.

And I'm sure this will play beautifully on the radio.

But this is the patch.

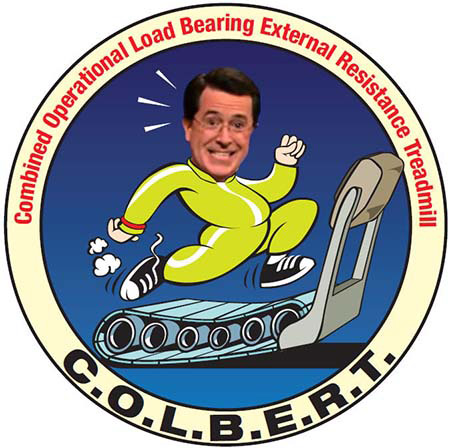

I'm holding the patch that is actually going to be put on what's called the Colbert, the Combined Operational Load-Bearing External Resistance Treadmill, which is...

So this is the treadmill that got named after you as a consolation for NASA reneging...

Lying to me.

After NASA lied to me and America and broke their own rules so much for scientists, they named a new treadmill after me, which is being launched in August.

And I hope to go down there for launch.

But I just looked at this treadmill and it's a little cartoon of me and my head on top of the cartoon, running on a treadmill and around it has my name, as all things must for my character.

And I saw this today and I thought, my goodness, is he insecure?

Does he need reaffirmation at all times?

And that's why he'll never achieve anything good, because it always has to be about him.

So going forward, you're not without power of influence, of people's feelings and moods.

I am enormously powerful, Neil.

No, your character is.

That's true, I forgot.

You're the geek, your character's got the power.

Exactly.

So what do you think you can do going forward?

We all know what the rest of us can do, but you have a unique platform.

I actually, I love having scientists on, and if I can have them on and add comedy to the fascination of their subject, then, well, that's just a honey ball that might make people swallow.

What I think is the real treat, which is excitement and engagement by questioning the world around you, because the world is so full of a number of things, I think we should all be as happy as kings.

And all you have to do is look for the question that you want to ask about the natural world around you.

And, well, then you are given the gift of a lifetime of entertainment and enjoyment just by being alive.

Stephen Colbert, thanks for being on StarTalk.

Oh, it's my pleasure.

Thank you.

I adore him.

I adore him, because he just capsifies what I'm seeing this whole show.

It sounds like you have a crush on him.

No, I do have a crush on him, but I also have a crush on what he's saying, because I think I don't have children.

I have nieces and a couple of nephews I don't like too much.

My dog.

But when I was a kid, do you know, I vividly remember being fascinated with sea monkeys.

Now I know that they're brine shrimp.

But at the time I didn't.

You know, on the box, you grew them into people.

And that's science.

That I wanted to grow my own little people.

I wanted to know how you did that.

And there was a wonder and an excitement when you're a child.

And as you get older, it wears off.

That wonder and excitement for science can wear off.

Somebody's got to keep the flame lit.

If you don't have a father who's a scientist, like he did, like you have and your children have, then it can wear off.

And I'm saying it's important to nurture that enthusiasm in children so that it keeps going.

Well, I have a slightly different view.

I think it's important to nurture that in adults where it's all worn out, because kids, it's there.

But it won't be worn out anymore.

Right, okay, keep it going.

Yeah, and ignite it in adults.

Right, right.

And then nurture it in children and say things like we're beautiful results.

I think that's awesome.

I'm going to say that all the time.

We've got a caller who has a comment, I think, about what scientists look like to others.

Is that Lyn calling from Boston?

Oh, another Lyn.

Lyn, you're not the only Lyn in the universe.

This is too many Lyns for you to handle.

Hello, Lyn.

Lyn, are you there?

You're live on StarTalk.

Did we lose Lyn?

I think we lost Lyn.

Lucky for you, you had a backup.

I'll go to my backup Lyn.

You cloned me.

So, Lyn, let me ask you, it all excites you, and it all excites Stephen Colbert.

The problem here is we're missing a link between the majesty of that frontier and the emotions of the public.

And your solution was make it a marketing campaign.

My solution is yes.

Why not?

Do that.

Do public service announcements, where you have sexy people getting out there saying, why are we here?

We have a little bit of that, because there's hit TV shows like CSI that have sexy chemists.

Why not do public service announcements?

Why are we here?

Why do we dream?

And then have a scientist like yourself come out and give the answer.

It's a brilliant idea.

I'll raise it with the authorities.

We do things where we let children...

When I was a kid, a science fair was an awesome thing.

So why don't we do more of that?

Why don't we do national science fairs and make big things about them?

Okay, so I think the problem is science fairs are only right now attracting the people who already know they're interested in science, and they're not igniting flames within those who never knew any different.

Right, we have America's Got Talent, I say national science fair.

Make that a new TV show.

A new primetime TV show.

Everyone comes on with their new science invention.

And we get Simon to judge them.

You and I will judge it.

Alright, Lynn, we're going to go to break.

We'll be right back with StarTalk.

If you have something to say to us, tell us at 1-877-5-STAR-TALK.

We're also online at startalkradio.net.

See you in a moment.

Bringing space and science down to earth.

You're listening to StarTalk.

We're back to StarTalk.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, astrophysicist, with my co-host, comedian and actress, Lynn Coplitz.

How are you, Lynn?

How are you?

Call us at 1-877-5-STAR-TALK.

You have a question about the role of science in your life.

Has it transformed you or just messed you up?

Which is...

I think we got Nick in LA.

Is that you, Nick?

Hi.

Nice talking to you.

Welcome to StarTalk.

What do you got for us?

Hi, Nick.

Well, I loved science ever since I was in high school and I took science for the four years that I was there.

What got you, Nick?

What first got you?

What got me?

What's the first thing that excited you about science?

What do you know?

E was MC squared and the relativity, because Einstein has always been fascinating to me.

And when they were going to select him for the Time magazine, the best 20th century man, I said they're going to pick Einstein, and they did.

And they did.

Yeah.

And I love that.

I have goosebumps.

That's cool.

She does have goosebumps.

I'm looking at them on her arm.

I think that's really cool.

So what was your question?

I think he's just sharing the story with us, right?

I just wanted to share the story and I love listening to Neil and I enjoy shows on Nova and I'm so glad that you're on on Sundays and I'm listening to you right now.

Nick, you don't like me?

Don't you like listening to Neil?

You got to start it.

I don't know you.

You're still learning about science.

I'm at the dinner party, though.

Oh, that's good.

No, I'm loving both of you in the feedback.

Thank you, sir.

Oh, thank you so much for your warm, honest response.

All right.

I think a quick question back to you, Nick.

So you were not interested as a little kid, but in high school, you're kind of older by then, right?

Yeah.

Yeah, okay.

So it took a few more years for you.

Did you have a cool science teacher?

I loved taking it every semester that I had it, and I just kind of followed it all along, and I read some of Einstein's works, and I got fascinated.

Plus, relativity is freaky, right?

I mean, it's freaky stuff.

Nick, did you have a cool science teacher?

Because I was saying to Neil, have you been listening to this show today?

I was saying that if you don't have a cool science teacher, then you're not ignited by science.

Well, you know what?

I didn't.

But somehow, I just got fascinated with it.

Okay, so something hit you.

Something hit you, yeah.

It just caught my interest in staying with it ever since I've been following you all along.

I love the Carl Sagan series, and now I get to watch Neil, and I get to learn all about black holes and everything.

We got a science junkie on the line here.

Please listen to us again next Sunday, Nick.

Yeah, thank you.

Thanks for calling in.

We got another caller.

I think it's a Lynn from Boston.

Is that you on the line?

Oh, she's back.

Hi, Lynn.

Yeah, Lynn, is that you on the line?

You're live on StarTalk.

Hey, Lynn, are you on the speaker phone, and are you drunk?

Okay, well.

She's drunk, well, that's good.

We're reaching my people.

Finally, my people are tuning in.

I don't know how many chances we'll give Lynn.

This is StarTalk.

We're talking about science in your life.

Let's go to Gary in LA.

Gary, you there?

I am.

Hi, guys.

Hi, Gary.

You're live on StarTalk.

You've been discussing the development in science.

I'm just wondering what is about to come for us now?

Is it genetics?

Is it engineering?

What's the next big thing science is going to deliver?

Average guys like me.

Excellent.

I love your accent.

What is the next big thing?

Okay, it's not an LA accent.

Gary, where's that accent from?

It is from the UK.

The UK.

I'm over in Los Angeles, and as I say, I really adore the show.

See, the Americans all...

Nothing like it on radio.

No, thank you.

Thank you.

Americans are jealous of the accents of the UK.

So science, of course, has many dimensions there, so I think in...

Answer his question now.

What is the next best thing?

Okay, I'm a little biased because I'm an astrophysicist, but I'm looking for life in the universe.

If we can find life other than life on Earth, that would be extraordinary, not only in astrophysics, but in biology.

Life that has its identity coded in some way other than DNA, that'd be really, really cool to know how nature figured out how to do that.

That's why I'm going to run through the list real quick.

We don't know what dark matter is.

Gary, what would be the cool thing for you?

What would you like to have discovered?

I think I agree with Neil to find something outside of our own planet that actually is living would really stop that lonely feeling that we have floating around on this rock.

Oh, Gary wants a little alien friend.

I'd like an alien friend.

Is it something, is it a genetic development, is it something that crosses over with engineering?

Do we get this Terminator Freak Show happening?

Oh, Terminator Freak Show, the intersection of genetic engineering and machine technology and computers.

That's an interesting one.

Science fiction writers, of course, take that to the future and they have them come back and kill us all.

But that's like technology gone awry.

But going back quickly to science, so we don't know what dark matter is, we don't know what dark energy is, we don't know how to go from inanimate molecules to animate life molecules.

We just don't...

So there's huge frontiers that I think will happen in our lifetime.

Plus, I want to go to Mars and I want to try to make that happen.

I want to try to find a couple more callers before we head out, but thank you very much.

Thank you, Gary.

Thank you.

All right.

Let's go to Perry in Pasadena.

Gary wants an alien friend.

Perry in Pasadena, are you there?

Yes, Terry.

Oh, yes, how are you doing?

Terry.

Terry, hello.

First of all, Neil, I really like the way you present what you really believe in.

I grew up, well, I was in high school in the early 60s in social studies.

You guys mentioned this earlier.

I was so excited.

I was on fire for what we were going to be doing, and so much of it didn't happen.

Oh, so you're one of the disappointed ones.

Do you think it's possible that profit has anything to do with it?

If there's not enough profit in it, they're not going to do it.

You know, I don't want to agree with that, but I think behind closed doors, I have to agree with you.

The science that gets done, that gets the best funding, is what somebody can make a buck off of.

So it tends to be commercial products.

What bothers me, and tell me if this bothers you too, you guys too, is that are we ever going to find a cure for cancer?

So much money goes into it.

It almost seems like they need us not to find a cure, so they can keep making that money.

I have a theory about something here.

Say it quick because we're running short on time.

If everybody did the very best they can, every moment made the very best product that they can, wouldn't you think we would have so much more and better than what we have now if they really put everything into it?

Yeah, I have to agree with that.

If everyone were fully engaged in all what they can do best, inventing things, there would be a completely transformed world.

It would be a transformed world, but it wouldn't be a capitalist society.

The whole point is, I mean, they have invented pantyhose that don't run, but they can't sell them because no one would buy them.

You'd buy one pair and that'd be it.

Lynn, tell me real quick, what's your favorite, what do you want to have happen in science, real quick?

From being a kid, what I always wanted.

I wanted Gilligan's Island.

I wanted the food on Gilligan's Island, the giant carrot.

I remember the giant carrot.

I remember.

And the spinach that made everyone stronger.

You know what I wanted?

I wanted my own private genie, like in I Dream a Genie.

You and every other guy.

You wanted a blonde woman stuck in a bottle, in a midriff, with a midriff show.

We got to go.

You've been listening to StarTalk Radio.

Funded by the National Science Foundation.

We'll see you next week when we'll celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Apollo landing.

That's StarTalk.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron