About This Episode

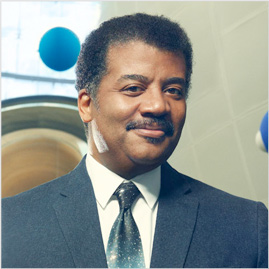

Why do rational people believe irrational things? On this episode, Neil deGrasse Tyson and comic co-host Chuck Nice break down media literacy, the psychology behind conspiracy theories, and how to combat our cognitive biases with author of Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational, Michael Shermer.

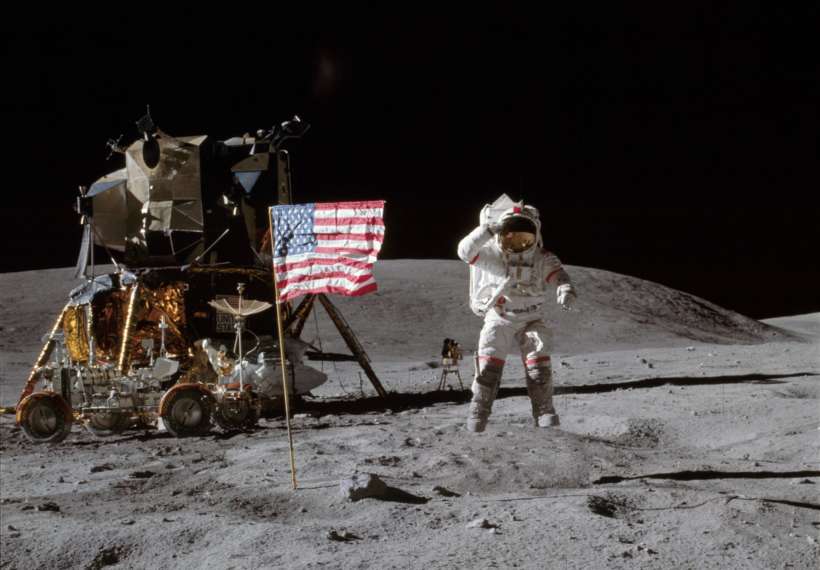

No one joins a cult thinking they’re wrong, so why does it happen? We talk about what it means to be a skeptic. Was 9/11 an inside job? Was the moon landing a hoax? Was the 2020 election rigged? Learn why popular conspiracy theories gained traction, what their fundamental problems are, and how to argue against them. Does the media make us more susceptible to conspiracies?

What cognitive biases stop intelligent people from making intelligent choices? Discover proportionality bias, confirmation bias, and hindsight bias. How do you know what to believe? If a conspiracy theory was a criminal trial, could you get enough evidence? What questions can we ask ourselves to avoid being biased? What would it take to change your mind?

Why do we often accept the supernatural but not real science? Why are there so many vaccine skeptics, but no antibiotics skeptics? Should Internet gatekeepers censor misinformation? Does being more educated make you less susceptible to conspiracy? All that, plus, is there such a thing as being too skeptical?

Thanks to our Patrons Zachary Vex, Alexandru Dolipschi, Chris Knopp, Gianni Gaetano, and D’Angelo Garcia for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can watch or listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTWelcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk, Cosmic Queries edition.

Neil deGrasse Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist.

I got with me my co-host, Chuck Nice, Chuck.

Hey Neil, how’s it going?

Welcome back on for another episode of Cosmic Queries.

Yes.

Inquiring minds want to know.

And the title of this one is, Why do people believe conspiracies?

Why do they want to believe conspiracy?

That’s what we really should call this.

Do we need a whole episode for that?

Because I could clear it up for you right now.

They’re stupid.

They’re stupid, stupid people.

We live in a nation of stupid people.

Good night.

We have, I guess, one of the leading, if there was a patron saint of skeptics, it would be this man, Michael Shermer.

Michael, welcome back to StarTalk.

Nice to see you guys again.

Oh, boy.

That’s a good start.

Well, if the intelligence is distributed in a bell curve, by definition, half of them are below the mean, so you may be right, Chuck.

No, no, except for like, we’ll be gone.

Everyone’s above normal, yes.

That’s very funny.

So let me just get a little of your bio out here.

Founding publisher of Skeptic Magazine.

And you’ve got your own podcast from Michael Shermer’s show.

I’ve been on multiple times.

Thanks for inviting me.

You’re a presidential fellow at Chapman University.

Where’s Chapman University?

Orange, Anaheim, Southern California.

Anaheim, okay.

And you have degrees in psychology, experimental psychology, and in the history of science.

Very important topic there, history of science.

You got a book this fall titled Conspiracy, colon, Why the Rational Believe the Irrational.

You see, good thing Chuck didn’t write that book.

Yeah.

He just said, you ain’t rational if you believe it.

My book would have been called Conspiracy.

What’s up, dumbass?

Stop.

Oh, boy.

All right, so Michael, I so…

I love Michael’s response.

He’s like, it’s going to be a long show.

So, you are deep in this topic your whole life.

I mean, it’s a career.

You’re a career skeptic.

And I just want to just enter on common ground here with you.

There are people who might say, I don’t believe the claims of vaccines because I’m a skeptic.

Right?

So, at what point do you say, no, you’re not a skeptic, you’re actually ignoring evidence?

At what point?

Because they might think that they’re trained to be skeptical of everything they hear.

How do you help those people?

Right.

That’s the rub.

Because nobody thinks that they are believing nonsense.

No one joins a cult.

People join groups that they think are good.

No one in the history of the world has ever self-identified as a pseudo scientist going down to their pseudo labs to collect pseudo facts to support their pseudo theories.

They think they’re onto something.

And so the question is, what does it mean to be a skeptic?

Really, it’s following the evidence.

And when there’s enough evidence to kind of tip the scales into belief with a small b and the truth with a small t, when there’s a consensus, you can say, yeah, okay, so I’ll accept it as provisionally true.

I’ll be willing to change my mind if the evidence changes.

But for now, I accept the Big Bang theory of, the theory of evolution, the germ theory of disease, global warming is real, vaccines do not cause autism, and are helpful for public health and so on.

So none of these are based on arguments from authority.

It’s that I know the scientific process works in a way that scientists themselves are competitive and they push each other to higher levels of evidentiary standards.

And so by the time it trickles down to me, I’m not a climate scientist, but if most climate scientists tell me that global warming is human caused and real, it’s reasonable to accept it because of all the competitive push and pull in the process to get there in the first place, right?

So in the case of conspiracies, it’s a little bit different because conspiracy theories are ideas about conspiracies, which is defined as two or more people plotting in secret to gain an unfair, illegal or immoral advantage over somebody else or some other group.

And that happens all the time, right?

So it’s not unreasonable for people to think, I’m suspicious that something might be up because it happens often enough in the real world.

Corporate America, corporations cheat to dodge the regulatory state or government agencies do things behind our backs.

And they don’t tell you and so there it is.

So wait, that brings up a very interesting question for me.

Okay, conspiracies are legitimate as conspiracies, but if they are done in secret, then how is it that you’re, how can you convince somebody that the secret has been exposed or that there was no secret to begin with?

Right, well, so you do have to have evidence.

So not all conspiracy theories are equal.

Which ones have evidence or not?

And what would you predict for evidence?

So for example, if WikiLeaks showed millions and millions of classified documents leaked to the public, not one mention of 9-11 as an inside job, not one mention of the hoaxed moon landing and where it was filmed and no memos about that, or just take your pick.

You would expect in a leakage like that, like with the Pentagon papers we found out all kinds of things that the government was lying about, but none of them had to do with the moon landing or anything like that.

It was like they lied about the Vietnam War.

Well, okay, that’s not exactly shocking.

Governments do lie to their citizens, right?

But you would predict if something, one of these other conspiracy theories that are popular were true, there would be some evidence for it in a leakage like that.

There you go.

So, Michael, in your book, you speak passionately, well, you speak passionately in many places, but the one that struck me was when you commented about the reaction of people to your 9-11 analysis that appeared in Scientific American magazine.

Scientific American is as pedigreed a place as you’d ever find the writings of science.

And could you just tell us a little bit about people’s reaction to you?

Right, so there I wrote about one of the little memes going around that, you know, that steel melts at 2,700 degrees, I think it is, and the jet fuel only burns at 1,800 degrees, therefore no melting steel, no collapsed buildings.

They must have used internal explosive devices, you know, demolition, intentional demolition.

Who did this?

It must have been the Bush administration, and you’re off and running.

Anyway, I just pointed out, I called that Fahrenheit 2777.

You don’t have to actually melt steel all the way, right?

You only have to weaken it.

It doesn’t have to become a liquid.

It doesn’t have to be a liquid.

It doesn’t have to be a liquid.

As blacksmiths know, it will melt the horseshoe to reshape it, right?

It just has to become malleable so that no longer can support the weight of the structure itself.

That’s it.

Don’t melt horseshoes.

That’s right.

Right.

And those buildings are heavy.

I mean, each floor is really heavy, right?

And from there, it’s actually a nice test case of how you know if a conspiracy theory is likely to be true or false.

How many elements would have to be involved, come together just perfectly in perfect coordination for it to happen?

How many people would have to be involved?

To plant explosive devices in a building, you have to break through the drywall and wrap this structural support beams in these explosive devices.

There must have been hundreds of them in each of the two buildings, two of the most secure buildings in the entire world after the Al Qaeda tried to bomb it in 93, right?

So how did they get in there?

Oh, well, they were there under the pretense of elevator repair.

Oh, elevator repair.

Then why are they nowhere near the elevators planting these explosive devices, right?

And also they would have had to know exactly which floors that the planes were going to hit ahead of time to put the explosive devices on those floors because that’s where the buildings collapsed.

The collapse started at those floors, at an angle.

Okay, Michael, you’re giving rational facts.

Why are they even relevant?

And by the way, here’s the most rational fact.

It was the Bush administration.

Come on!

Yes, right.

And the people that believe this, by the way, also think this is the most incompetent presidential administration we’ve ever had.

And somehow, they pulled off the most sophisticated conspiracy of all time, right?

And no one that was involved wants to go on 60 Minutes and write a tell-all book, or somebody that knows somebody that was involved in this.

And become independently wealthy, for having done so.

Let’s get to our questions.

I don’t want to ask questions that I know we got people who are asking.

So, Chuck, what do you have lined up?

Alright, so this question.

For Michael here.

This first question.

Michael, it looks all comfortable in his chair there.

It looks like my captain’s chair.

It looks great.

I mean, that’s a good chair.

Let’s see if we can destabilize his chair with these questions.

So, this first question is from a superfan named Chuck Nice.

He says…

Chuck, are these Patreon members?

And are you still not a Patreon member?

We won’t get to ask questions if you’re not a Patreon member.

Okay, I do have a question I want to ask.

It’s a personal question for Michael, but I’ll get to our Patreon members first.

Here we go.

Kevin de Semoyer says, do most conspiracy theories get conjured up because of Hollywood films, or is it more the mistrust of government, or is it a combination of the two?

Well, it’s a combination of the two and many other factors as well.

Politics plays a role, but in general, if a film comes out that’s very popular, like JFK in 91, Oliver Stone’s film.

The Oliver Stone retelling.

Yeah, I mean, it was a well-made film.

I mean, it’s compelling, you know, back into the left, back into the left.

Kevin Costner is repeating this and is like, oh my God, he must have got shot from the front.

And until you dissect the film and you pull out all the mistakes and errors and exaggerations and incorrect inferences and so on, there’s really not much there.

But yeah, so films drive it, make it popular for a while.

I mean, there were some actual studies done after JFK was released in which the percentage of people that suspected the government or somebody was involved besides Lee Harvey Oswald went way up.

It’s always been above 50% since the Warren Report.

This is kind of the mother of all conspiracy theories.

It never dips below 50%, but after the film, it got bumped up.

So, you know, I have a whole chapter on that because it’s one everyone’s so interested in.

There’s a whole industry of books and films about it.

But, Michael, you commented that World War I began in a bit of a…

had some conspiracy roots to it.

And that’s before we had modern media, even before films.

So, there must be something deeper within us that’s not so much slave to media that we still want to make this happen.

Right, because conspiracy theories go all the way back to ancient Rome, right?

The plot to kill Caesar and so forth.

Or when Rome burned, there were conspiracy theories about, you know, Nero made it happen on purpose, my hop, or he let it happen on purpose, lie hop, right?

This is a very old idea.

Even, you know, Roosevelt was accused of letting Pearl Harbor be bombed or making it happen on purpose.

Just to get us into the war.

Yeah, just to get us into the war.

Well, because why else line up the ships that way?

Yes.

Like sitting ducks for the bombers, right?

Because if everybody, if there’s one thing we all know about America is we will resist getting into a war at all costs.

Well, see, I call this, instead of my hop or lie hop, I call this cow hop.

Capitalized on what happened on purpose, right?

So it’s not that Bush orchestrated 9-11 or let 9-11 happen, but he certainly capitalized on it to follow his own agenda, as did Roosevelt, who wanted to get the United States into the war to support Great Britain against Germany, couldn’t do it without some event, and that was the event.

So politicians do do that, and they do so in secret often, and I have old chapters on all the shenanigans.

The CIA has been up to in the 50s, 60s and 70s, MKUltra dosing US citizens with LSD and other mind control drugs, because we didn’t want to fall behind the Russians and the Chinese and the North Koreans in mind control technology, or planting spies in social justice organizations like AIM, the American Indian Movement, feminist movement.

Are you telling me we fell behind in a mind control gap?

Is that what you’re saying?

Just exactly like there was a missile gap, there was a fear that we’re behind the Russians on mind control, there’s a mind control gap.

But it turns out the Russians were making us think that we were behind all along.

Don’t get meta on me now, Chuck.

That’s actually a thing, Chuck.

That’s an agent of disinformation.

They’re purposely leaking information that’s false that sends us down the wrong track.

UFOs are subject to that.

There’s a lot of people that think that the government is very amused by all the talk of UAPs and UFOs because it distracts the public from what they’re really doing, whatever that may be.

Right, right, right.

Wow, God.

All right, here we go.

This is Stephen Sommers.

Stephen says, greetings, Star Gazers.

Please, what are the top three cognitive biases that prevent intelligent people from making intelligent choices?

Yeah, so this is the core of the subtitle of your book where you make the assumption, contrary to Chuck’s book, that he hasn’t written yet.

Michael, you are granting the person the power of rational thought and then posing the question, how does a rational person believe in such a thing?

So where does the rationality get driven off the cliff?

Well, in fact, back to where we started with Chuck’s comment about intelligence, in fact, intelligent people are really good at rationalizing beliefs that they hold for non-intelligent reasons.

That is to say, most of us believe all sorts of things that we didn’t arrive at through evidence and rationality and smart people are really good at that.

The confirmation bias, only seeking confirming evidence for what you already believe and ignoring the disconfirming evidence.

The hindsight bias after something happens, it seems obvious why it happened and we should have known it happened like the August 9th, 2001 memo from Condoleezza Rice you know, Al Qaeda to strike US on US soil.

How come the Bush administration didn’t do anything about that?

Well, because there were 10,000 pieces of intel every week about what that title was up to.

And only after the fact do we go, oh, that’s the one, we should have known that that memo.

Let me add, you know this, but I just want to add because I come from the universe here, that for the shuttle disasters, right?

Once you have the disaster, you then look and find the memo from an engineer saying they should launch for those reasons.

And for successful launches, you don’t engage in that same search where you might find as many or possibly even more memos that give just the same kind of warning.

So, continue, Michael.

It’s very simple.

It happens to everybody probably on a daily basis.

Let’s just say, for instance, you’re about to drive to work and you say, should I take Elm Street or should I take Pine Street?

And because you had that thought of the choice between Elm and Pine, you get on Pine Street, it’s backed up.

You automatically say to yourself, I knew I should have taken Elm Street.

You say that.

I knew I should have taken Elm Street.

Something told me to take Elm Street.

No, what you did was you equally weighed both and decided on one, but in hindsight, the other seems like it was your choice because otherwise, you’re just stupid.

Exactly right.

So hindsight bias sounds pretty pernicious, but the questioner asked, is there a third bias that we put at the top of this list?

Let me just riff on that one more time because, and by the way, Chuck, Elm Street was one of the streets that the Kennedy, that JFK turned off of into the Dealey Plaza.

So interesting you picked that one, huh?

I wonder if that was random.

He should have turned on Oak Street.

Actually, Michael, before we get your third bias and before you flush out what you just said, we’re going to take a quick break and when we come back more with Michael Shermer, he’s got a new book out on conspiracy theories and why rational people might think irrationally about them.

We’ll be right back on StarTalk.

I’m Joel Cherico, and I make pottery.

You can see my pottery on my website, cosmicmugs.com.

Cosmic Mugs, art that lets you taste the universe every day.

And I support StarTalk on Patreon.

This is Star Talk with Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Thanks for watching.

We’re back, StarTalk Cosmic Queries.

Michael Shermer, patron saint of skeptics, not only on earth, but across the universe.

I’m pretty sure, I’m pretty sure.

And Michael is an atheist, so for me to call him patron saint of anything.

So I mean that in a metaphorical sense, Michael.

So Michael, the question was, what are the three top cognitive biases that would lead someone to think conspiratorially?

And we left off with the hindsight bias, which is particularly pernicious, right?

What else you have going there?

Well, then also we missed the events that didn’t happen.

So there’s no conspiracy theories about Hinkley shooting Reagan because Reagan survived.

Had he died, he very likely, there would have very likely been conspiracy theories about who was really behind Hinkley besides that mental illness, something like that.

The third one, I’d say proportionality bias it is.

We want to proportion causes and effects.

They should be roughly equal.

If you take a little stone and some physics for you and you throw it a little bit, it doesn’t go very far.

If you throw it hard, it’ll go much farther.

So we think of cause and effects.

If I put a lot of effort, if you ask subjects to roll a dice and try to get a low number, they kind of throw the dice gently.

And if you want them to get a high number, they really throw the dice as if like-

That is great.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

It’s hilarious.

That’s really funny.

So if a big event happens-

If you gently drop the dice, oh my God.

I’m gonna get a one or a two.

No, I want a five or a six, right?

So in terms of conspiracy theories, if a big event happens, so Reagan survived, so okay, it wasn’t that big of a thing, but JFK didn’t.

So what’s the cause of Kennedy’s death?

It’s gotta be, the most powerful person in the Western world’s gotta be something equal, right?

So Lee Harvey Oswald is a lone nut with some psychopathy and whatever mental issues he had.

That doesn’t feel right, right?

So you gotta add elements, you know?

So the KGB and the FBI and the CIA, the Cubans and the mafia and the Russians.

So you’re just cranking it up.

Right, to make it match, right?

To the jack of a car until it causes a match effect.

The Holocaust, one of the worst things that’s ever happened in human history, committed by one of the worst political regimes of all time, the Nazis.

There’s a kind of a cognitive balance there.

Or just take 9-11.

You’re telling me 19 guys with box cutters managed to pull this off.

This is the kind of thing you hear.

No, it had to be something massively big because it was massively big.

Or Princess Diana, cause of death, drunk driving, speeding, no seat belts.

Tens of thousands of people die in automobile accidents for those three reasons.

But princesses are not supposed to die by the same way that the rest of us, hoy, poy, die.

So it had to be the royal family and Prince Charles and the MI6 and so on had to be involved.

Her brown-skinned boyfriend.

Right, yeah.

Yeah, oh man, so proportionality.

Chuck, you had to go there, you had to go there.

Come on, that’s still a big deal.

Everybody thinks that.

Still a thing, still a thing.

But so Michael, we mentioned JFK, mentioned 9-11, are there conspiracies, like the mothers of all conspiracies, that we can learn the best lessons from so that we can then walk away and apply it to our Thanksgiving dinner and any other conversations we might encounter?

Well, let’s just take the rigged election conspiracy theory.

Please.

You and I, how would I check?

Please, yes, were you being Henny Youngman there?

I’m like, please.

Yeah, please, take it, take it.

Take it anywhere, just take it.

Throw it in the dumpster.

Well, okay, so first of all, there’s always election anomalies.

If you go and search for them, we call that anomaly hunting.

And in other countries, there are rigged elections.

I mean, the CIA famously was involved in rigging elections in South American countries in favor of fascist dictators over communist dictators, because at least they’d be friendlier to US industrial interests, business interests and so on.

Our government did that, right?

So it’s not unusual for people, it’s not unreasonable for people to be a little suspicious of that.

And if you look in past elections, almost every time, every losing party thinks that the other party was up to something.

There were some shenanigans there in Ohio, or there was some quirky thing in Iowa and so on.

So what’s the take home here?

How do you know what to believe?

What’s true?

What’s justified true belief?

And the definition of knowledge.

Well, the justified part.

Well, how am I gonna determine if, I don’t know, what that van was doing at three in the morning when it pulled up behind that building in Georgia somewhere, and there was a grainy video of this, and you can’t quite make out what’s going on, but it looks like they were bringing in boxes of votes.

Maybe there was something to it.

I wouldn’t even know who to call, right?

So you have to have some trust in institutions that do confirm these things, that do look into these things, right?

So when Attorney General Bill Barr, appointed by Trump himself, and who is a lifelong Republican, and who would be motivated to find some kind of fraud, couldn’t find any and said, we didn’t find anything.

The election was totally legit.

That should have been the end of the story when society is normally structured in a way where you trust institutions like that.

But that’s not the world we live in at the moment.

People don’t trust science like they used to, or the CDC, or scientists, or professors, and they certainly don’t trust politicians anymore.

So that’s a big problem for us now.

So I wanna actually save that for the third segment because we wanna know, we need some positive thoughts at the end of this, how do we rebuild confidence in institutions?

But I wanna save that for the third segment.

Chuck, why don’t you give me another question?

Okay, let’s go to Ruud van der Linden.

Ruud says, hello Neil, hello Chuck, hello Michael.

Ruud from the Netherlands here.

I’ve got a question.

Scientific research after COVID indicated that people in countries where government trust was high got vaccinated more often.

If this is true for misinformation as well, does high distrust equate to more misinformation circulating or he’s basically, is there a proliferation of misinformation when the ground is fertilized by mistrust, basically is what he’s saying.

Yeah, indeed it is, right?

As the example I just gave, if you don’t trust any voting institutions to run a legitimate election, no one’s gonna believe it.

So I am worried about that for 2024.

And Chuck, what’s a common fertilizer but bull poops?

Bull shit, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to upset it.

I’m sorry.

You said fertilize.

I said fertilize, right.

Yeah, however, I mean, that just begs the question then.

Why don’t I believe, like if you’re talking about an election, why don’t I believe that it was rigged when my guy won if the whole thing is crap to begin with?

So if you don’t trust the institutions, that means the institution of elections are rotten.

So very important question there.

And this is the, I only complain about the UMPs when they’re.

Right, when they call a strike against my team.

Against my team, right.

Yeah, that’s called the my side bias.

It’s certainly quite strong.

We notice.

Damn, Michael has names of all of these bias, man.

It is so great to put names to this stuff.

I wish I was that fluent.

Man, that’s a my side bias.

Cosmologists and astrophysicists, you’re not the only one to have cool names.

I know.

So the my side bias.

Every sporting fan probably can admit to my side bias, even though they don’t want to.

But what normally happens though in previous elections is that after a while, the losing side drops the conspiracy theory and they start focusing on the next election.

This is unusual what we’re going through now where Trump has kept it alive and only because he still has some political pull in the GOP is anybody saying that there’s anything to it.

We know from the January 6th hearings that none of the top people believed the rigged election.

They believed Barr.

When Barr said there was nothing to it, then that was it.

But wouldn’t the conspiracy be Barr has been bought out or he’s…

Yeah, there is a conspiracy theory about that.

Just to maintain the thought, you have to keep going at the conflicting data.

That’s right.

Yeah.

All right.

Well, this is Cicero Artefan and Cicero Artefan.

Right?

No, that’s the name of an artist in the Louvre.

That’s not anybody’s real name.

This afternoon, we shall be surveying the works of Cicero Artefan.

The very first artist to take Cubism and Impressionism and put them together.

All right, here we go.

Cicero Artefan.

Isn’t that great?

Oh, by the way, just a quick thing.

I had an occasion to have a chat with Rob Reiner recently.

Meathead from All in the Family.

Yeah, anyway, so I don’t know if he did this.

So he had an idea, it was brilliant.

He said, imagine that there’s, he was gonna make a movie where there’s this big institution with big columns on it and stairs that lead up to it.

And it’s just called They.

That’s funny.

Okay, and so they say, well, they say that, really?

And then you go in there and there’s this whole set of committees and the typewriters going away and out comes a statement.

They say that what goes up must come down.

And it’s the place where they communicate with the rest of us.

That’s pretty funny, actually.

That’s pretty funny, yeah.

I like it.

All right, so.

Okay, so what else you got?

Cicero Artifon says, hi, Dr.

Tyson, hi, Dr.

Shermer, and hello, Lord Nice.

Cicero from Toronto, Canada here.

What kind of questions should I make when I’m dealing with a situation that I would like to avoid being biased on an issue?

So, how do we self-assess to make sure that we are not falling prey to all these wonderful biases that you have pointed out to us?

Hear the mirror.

Yeah, how do you, because if I think, like you said, Michael, if you think you’re rational, like you said, no one ever said, I’m going to my pseudoscience lab to find pseudoscience results so that I can be a pseudoscience.

No one says that.

So how do you self-check?

That might be impossible at some level.

Well, it’s not impossible because it does happen.

We know that scientists are subject to all these same biases, but they can’t let themselves get away with it because their colleagues will call them out on it, right?

So you have to think, if I was reading my paper here or my research as a critic, what errors would I find?

What mistakes of reasoning would I see that I personally can’t see?

So you have to kind of mind read.

You have to put yourself in somebody else’s, a critic’s shoes.

You also have to check your ego at the door.

Or just have my mother as your mother.

Don’t worry.

She will tell you all the stuff you did wrong and every single place you failed.

Chuck has continued his therapy sessions into StarTalk programming.

Yes, I have.

So you have issues with your mother, Chuck.

Okay, this is interesting.

Yeah, it’s a whole other thing.

Yeah, just don’t edge them on, Michael.

Oh, I’ll tell you what you should do, Chuck.

You should go to your local Scientology center and tell them this while you’re holding the little cans doing the E-meter readings and tell them about your mother.

Oh, they’ll have a course for you to take.

It’s only $10,000.

That’s only 10 grand?

Okay, that’s a, what a bargain.

Okay, a couple other questions you can ask yourself, like what would it take to change my mind?

Because almost nobody tries to kind of falsify their own beliefs.

It’s almost impossible to do.

People find a pattern and then they find, search evidence to fit it.

Michael, I’m in complete agreement with that.

I’ve attempted that in a few cases and it really puts people back on their heels without you coming across as being aggressive, right?

If you just say, and they’re quick to say, well, what would change your mind?

But I don’t go into that question unless I have an entire litany of things that would change my mind.

So there’s research by a psychologist, Peter Wasson.

So this is one of the Wasson tests.

So if you give subjects like a series of numbers, like two, four, six, what is the rule?

So people go, I think the rule is probably increasing numbers by two even numbers.

So then they’ll go like, all right, 10, 12, 14.

And the guy goes, yep, that’s correct.

Okay, 56, 58, 60.

Yep, that’s right.

And they’ll go, well, that’s it, that’s the rule.

And it’s like, no, that’s not the rule.

And no one ever says like, well, one, seven, 13.

And the rule is something very simple, just increasing numbers, that’s it.

A sequence, right?

But no one tries to falsify it.

They go, well, I think I figured it out.

It’s two, four, six, so it’s increasing even numbers by two.

That’s the rule.

Why didn’t you ask some other sequence just to see if that would violate the rule?

And so Watson’s conclusion was, is we only try to confirm hypotheses.

It’s very difficult to get people to try to falsify their hypotheses.

And this is what you have to do.

I like that, I like that.

That’s tremendous.

Tremendous, I mean, that, and what a, I mean, that’s an exercise I don’t think many people are going to want to engage in.

Because one, it’s arduous.

It’s really tough on your own psyche.

And two-

But Chuck, if I say, convince yourself that you’re not funny.

Right.

You know, seriously.

I couldn’t do that.

And my response would be, there are audiences all over the world who have done that for you.

Well, whether or not that’s true, you’ll come back to me and say, F you too.

Right, exactly.

It’s a tough, tough thing to do.

Man, I gotta tell you, this is a great show.

Everybody in this country needs to be watching this show right now.

All right, here we go.

This is Alejandro Reynoso, rich Corinthian leather.

Let me guess, he’s from Monterrey.

He is from Monterrey, Mexico.

And he says, hello.

He’s a regular on this, so we got this rehearsed at this point.

Hello.

So what do you have?

What should I say?

Hola.

He says this, how do you-

And by the way, I’m assuming he’s not offended by this.

I hope not.

Because he keeps writing in.

He keeps writing in, so.

I mean, you know.

I mean, he asked some pretty decent questions too, so you know, anyway.

He says, how do you deal with a world that accepts so much pseudoscience and supernatural things, but then denies real science?

You know, I mean, I don’t know.

How do you explain that?

I don’t know.

So supernatural, like religions and things and ghosts?

So anything supernatural, whether it’s ghosts, whether it’s religions, you know, you can say, you know, bordering on extraterrestrials, you know, where there seems to be this willingness, if not a willingness, an almost eagerness to believe things that are mystical and magical and, you know, that are, you know, fantastical.

You know, we found the remains of a dragon, but, you know, when we unearthed it, it turned to dust.

But we got this blurry picture of it right here.

See?

Like, you know, what is it in us?

Is there something in us that makes that, like, happen?

When we come back, we’ll try to give Michael Shermer a chance to answer that question.

We’re going to take our last break, and when we come back, Michael Shermer, tell us about his recent book.

A book that sounds like required reading for anyone who is a citizen of the world.

How about that?

How’s that for a prerequisite?

I love it.

All right, we’ll be right back, StarTalk.

We’re back, StarTalk Cosmic Queries.

Got a long time friend and someone I deeply admire, Michael Shermer, who’s, as I’ve said, the patron saint of skeptics on Earth and across the universe.

And I’ve confirmed that, Michael, you can put that on your resume, I think.

Of course, I got Chuck Knight.

Chuck, we can find you on social media.

Yes, sir.

Chuck Nice comic, you’re there.

Yes, sir, thank you, thank you.

And Michael, share with me briefly your social media footprint.

Oh, well, on Twitter, Michael Shermer, and michaelshermer.com for my web page, skeptic.com for the magazine.

Here’s what the magazine looks like.

Skeptic available in bookstores.

For those who can watch it, yeah, yeah, uh-huh.

skeptic.com and so on, yeah, that’s it.

That’s right, it’s in well-stocked bookstores that have sort of periodicals in them.

You can find it there.

And I think Barnes and Noble’s among them, even.

So we left off, I think, a very important question, Michael.

There are people who just simply embrace mysteries and the unknown.

And are you taking this away from them?

Are you just a curmudgeon and you’re no fun?

I want there to be dragons.

I want the aliens to have come.

I want all of this.

Why are you taking away my fantasies?

Well, first of all, doesn’t the truth still matter?

I think so.

And 500 years ago, everybody believed pretty much the entire world was ruled by demons and gods and angels and so forth and witches.

And I call it the witch theory of causality.

Everything was caused by witches of some sort and other demons and so on.

And diseases, accidents, storms, droughts, starvation, it all had supernatural explanations.

And we didn’t lose anything by getting rid of all that most of those.

There’s still mysteries to be solved.

And here is where the mind fills in the gap with something.

The God of the gaps argument, it’s God.

Or in the case of conspiracies, if it’s a big event, like no one who has a conspiracy theory about the yearly flu epidemic that sweeps around the world, right?

But if it’s something huge like COVID-19 or the AIDS epidemic, for a while that was thought to be targeting the black communities or the gay communities by the CIA, that kind of thing, because of Tuskegee and other kind of shenanigans, the CIA was up to dosing American citizens with mind control drugs, as I mentioned.

If the CIA could do that, maybe they planted AIDS in inner city.

But no one has conspiracy theories like that for, again, the flu or antibiotics.

Why are there no antibiotics skeptics like there are vaccines skeptics, right?

It just depends on the effects, and the bigger the effect, the more likely it is you’re gonna get some kind of extra causal vector thrown in there, a secret conspiracy, a cabal, you know, it was the demons, it was Satan, something like that.

So it’s a way, it’s a causal explanation.

You know, we want explanations for things.

It’s, you know, uncertainty is uncomfortable.

And, you know, as discombobulating as it might be to think that there’s 12 people called the Illuminati running the world and doing a crappy job of it, it’s even more discombobulating to think that-

It’s even more disconcerting to think that nobody’s running the world.

Nobody’s in charge.

It’s just mostly chaos and complexity, emerging properties, you know, why is inflation going up?

Well, this guy says this and this economist says that, who knows, right?

It’s, you know, it’s like, what?

You mean no one’s running the show?

It’s just us?

Yeah.

Well, isn’t that, I’m sure you have a term for this, but because we have to blame somebody or something.

Okay, what’s your term for that?

Well, yeah, I don’t think I have a term for that.

Well, actually there is one, you know, so I call this agenticity or intentional, you know, the kind of hyper agency detection that is, we tend to see patterns in random noise and infuse those patterns with agency.

There’s somebody behind the scenes making that happen, right?

So much of the world operates randomly.

There’s just a lot of statistical randomness that explains things, but it’s hard to see randomness, right?

So, you know, just take the stars in the sky.

That’s what randomness looks like.

It looks like big dippers and little dippers and scorpions and fish and horses and things like that, right?

The patterns of randomness actually in our minds look like things.

So if you get a random, you know, cancer clusters as they’re called, you know, those are mostly just random, but people see the pattern of that somewhere.

The example I like to use is when Steve Jobs first came out with the iPod and they had the random shuffle feature where your music will play randomly.

And people complained to Apple saying, well, it’s not random.

Certain songs come up more than other songs.

Like that’s randomness.

You know, if every song came up equally as well as every other song, you’d have to program that.

So Michael, they changed that.

So now random means randomly, but don’t repeat a song until you get fully through the list.

Oh, interesting.

That option’s not available.

Interesting, I did not know that.

Purely random is not there anymore.

Right.

Right.

Look at that.

We are so stupid as a society that we forced Apple to change the definition of random so we could be comfortable listening to our stupid MP3 players.

Jesus!

Okay, nevermind.

All right, Chuck, let’s go lightning round here.

This is On Internet Influence.

This is Steve Murphy.

Hi, Dr.

Shermer, Dr.

Tyson, Lord Nice.

People can research a conspiracy online and probably find just as many articles that support the conspiracy theory as the bunk it.

Should gatekeepers censor or flag media supporting false conspiracies?

If not, if not, what do we do?

Well, my lightning round quick answer is no, we shouldn’t censor those ideas.

And media companies can just tag them like they are with vaccine questions, vaccine articles that doubt it.

Here’s a good article that supports vaccines or rigged election claims.

So the gatekeeper is a gate tagger.

Yeah.

At that point.

Interesting.

That’s not censorship.

That’s just more information is good.

More information.

I love it.

I love it.

Labeled them excellent.

Frederick DeKamp says this, Hey, I love this podcast.

I listen all the time.

My question is, do you think that science denying people will lead us all to extinction?

You can’t say yes to that.

You just have to say no.

And we’ll move on to the next question.

Next question, please.

All right.

I don’t believe you believe that, Michael.

Part of me says he’s packing up.

He’s stockpiling food in his basement.

Just in case.

So Michael, just to give a little seriousness to the question, generally in my public rhetoric, I say that I don’t mind what people think anything.

The problem comes about if such people rise to power over laws, legislation and influence governments in society.

So what do you do if such a person gains a following and then they get elected and they do have such power?

Well, that’s why you should vote, right?

This is why we should have a voice in a democracy like that.

That’s all really all we can do and try to keep people like that out of power.

You know, in a free society, they can have a web, they have their own podcast or like an Alex Jones type person.

He’s unlikely to be the lead anchor on ABC News, right?

So, you know, those gatekeepers keep people like that out for a good reason.

They’re not following the rules of rationality and fact checking and editing that journalism has.

So, or in politics, hopefully, but our political system is not perfect.

So those kinds of people do occasionally get into positions of power, but not often.

And as, you know, much as it’s fun to pound on Trump, you know, he’s not president anymore.

Biden’s in there.

So, however bad you think it was, January 6th and so on, we still had a peaceful transfer of power and things are still going along like they usually do.

Right.

Okay.

Wow.

For now.

For now, yes.

Right, I’m not prophetic.

Right, all right.

All right, here we go.

This is Connor Holm.

Connor Holm says, hi Neil, hi Michael, hi Chuck.

I’m going to condense his question.

Sorry, Connor.

Is there any correlation between education and not believing in science?

I found that my undergraduate degree taught me how to determine a source’s credibility, while my graduate degree taught me how to better understand the actual science and its significance.

So clearly he believes it.

So what are the data show, Michael?

Yeah.

Like high school, there’s a whole section in your book on this, so why don’t you just tell us where you went there?

Yeah, so education does attenuate belief in conspiracy theories and pseudoscience and things like that.

Attenuate is an SAT word.

It reduces the amount of superstitious thinking.

Let’s put it that way.

And other irrationalities, but not as much as you might think, right?

So having a graduate degree is better than having a BA and having a bachelor’s degree is better than having just a high school diploma in terms of the kinds of things you would believe that turn out to be nonsense.

But not that significantly.

As I mentioned, smart people are also really good at rationalizing beliefs they hold for non-smart reasons.

And they’re subject, smart people are subject to the my side bias, the confirmation bias, the hindsight bias and so on, just like everybody else.

So it helps, but it’s not a cure-all.

And so is there any understanding as to why it’s not?

Should we teach different things in school, for example?

Well, in terms of science education, yes.

Of course, you know this, Neil, that it’s teaching how scientists think is probably just as important as scientific facts.

You remember that study showing that some significant percentage of Harvard grads couldn’t explain why we have seasons.

They thought it was how close the earth is to the sun, right?

How did they get through Harvard without knowing something basically like that?

It’s probably online.

It’s a short educational video called A Private Universe.

And it’s a freshly minted Harvard graduates.

They still have their robes on.

And they’re asked, you know, how do we have, why do we have the seasons?

And they’re up there saying, oh, well, because the earth’s orbit around the sun is not a perfect circle.

Sometimes we’re closer, and that’s what makes it hotter.

And these are Harvard graduates.

And the title, A Private Universe, is in your own head, you create your own worldview and make everything fit into that worldview.

And you will speak with confidence, even not knowing that you’re wrong, simply because it fits your worldview.

So thanks for remembering that, Michael.

That was an important video made some few decades ago.

The takeaway here, people, Harvard, a waste of money.

And just to be clear, maybe this audience doesn’t need it, but we have our seasons because of whether our axis is tilted towards the sun or away from it.

Because consider if we, just because what the Harvard graduates embarrassingly didn’t think about was, if it was summer because we were closer, that means it would also be summer in the Southern hemisphere.

But it’s not, they have the opposite run of seasons there.

So they were not thinking this through.

So right, that’s $70,000 down the drain.

I see we get a couple more questions in, go.

Okay, here we go, Scott W.

Peterson says, Dr.

Shermer, to answer the book’s subtitle, because they are not in fact, rational.

This is my point for the whole show, thank you, thank you.

He doesn’t need to answer that, but just let’s keep going.

Then he says, seriously though, I was thinking the other day that people hold on to fact-tastic beliefs in the face of mountains of evidence, to the contrary, because to do otherwise would mean admitting that they are wrong.

Maybe they’re too embarrassed, ashamed, or something else.

So is there a psychology behind this that says, hey, look, man, I gotta stick with this game.

I gotta see this hand through.

I already bluffed my way this far, and now I gotta go all in.

It’s a poker game, that’s right, interesting.

I bluffed my way in.

I bluffed my way in, now I can’t back out.

I gotta go all in.

Mm-hmm.

Right, that would be an example, loss aversion, where we are afraid to give up on something that we’re too committed to because we’ve already lost things.

And so you kind of chase after bad money or stay in a bad marriage or stay in a losing business or hold on to losing stocks because we’re already in.

So in terms of beliefs, the more committed somebody is to their religious belief or their political position or whatever it is, the harder it’s going to be for them to give it up.

So if you confront somebody, say at the dinner table at Thanksgiving and they bring up climate change or vaccines or whatever conspiracy theory they’re into, you can’t just say you’re an idiot.

First of all, you can’t just say you’re an idiot to believe this, right?

Because then they’re not even going to be listening to you anymore.

I’m in trouble.

But you have to make sure that when you’re countering their beliefs with facts that go against them, that they don’t feel like they have to give up their whole worldview.

Like the example I use, if you give people choice…

All right, listen respectfully, nod, ask questions.

Right, he’s got a whole set of rules, how you do that, which everyone should read before Thanksgiving, definitely.

Oh yeah, actually read it after Thanksgiving, because I love that argument at the table.

All right, here we go.

This is the artist formerly known as James Smith.

He says, hello all, this is James from Indianapolis here.

So Dr.

Shermer, what do you have to say to those flat earthers out there?

Do you think that people just follow the skeptic train right down the skeptic hole of misinformation?

Is there such a thing as miskepticism?

In other words, are people sometimes skeptics to a fault?

Thank you, have a great day.

I mean, you have to believe things just to get out of bed and get out the door, you know, that the society is going to function, my car is going to start, the money is still in the bank.

We make assumptions about the world that otherwise you couldn’t function.

And we do that for the most part, I think with science, you know, most people accept most of what scientists tell them without themselves knowing much about it.

It’s only when it bumps up against, again, like a religious belief, oh, I don’t know about that evolution thing, because do I have to be an atheist to accept evolution?

Because I don’t want to be an atheist, you know, something like that.

Or, you know, if you’re talking to a climate denier, a climate skeptic, you know, I find myself usually all of a sudden, we’re talking about free market capitalism and the American way of life.

And it’s like, how did we get from CO2 gases to capitalism?

Because that’s what they’re really concerned about.

Right.

If this is true, then do I have to give up this other stuff, I believe?

Absolutely.

Oh man, that’s just great.

Very central.

I like that, I like that.

Guys, I think we’re out of time.

Oh, this show is so good, it can’t be out of time!

Jane, I can’t be out of time.

Please!

We want more, I guess.

No, you can buy his book, buy the man’s book.

Well, I mean, that’s a no-brainer, and everybody hears this, better go get this book.

I mean, see.

The conspiracy and the subtitle, Why Rational People Believe the Irrational?

Did I get that right?

Here it is, Why the Rational Believe the Irrational.

All right, guys, Michael, it’s been a delight to have you back on.

All right, boys.

Thanks for thinking of us on this book tour.

And the publisher is?

Oh, Johns Hopkins University Press.

Johns Hopkins University Press.

Good one.

All right, guys, let’s hope for a more skeptical future so that civilization can survive itself, where we all have doubts.

And, but with folks like Michael Shermer running around, maybe there’s some hope, I would say.

Mike, always good to have you.

Chuck, always good to have you too, dude.

Always a pleasure, man.

All right, Neil deGrasse Tyson here for Star Talk Cosmic Queries, as always.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron