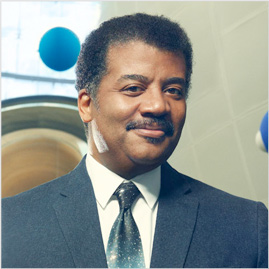

About This Episode

How does physics impact our free will? On this episode, Neil deGrasse Tyson and comic co-host Negin Farsad discuss quantum mechanics, parallel universes, and the theory of everything with theoretical physicist and author of The Biggest Ideas in the Universe, Sean Carroll.

What would it mean to discover what comprises dark matter and dark energy? We discuss our theories on dark matter and how dark matter behaves. Is there such a thing as dark light? What questions keep Neil and Sean up at night? Find out about the incompatibility between gravity and quantum mechanics.

Discover how the universe doesn’t always conserve energy. If photons lose energy as the universe expands, where does the energy go? Learn why the traditional image of an atom is wrong, superposition, and why Sean thinks there are parallel universes. We discuss the role of free will in physics. Could the laws of physics make our universe deterministic? Is there free will? Will we need another once-in-a-generation genius to come up with the theory of everything?

Discover Leiman Alpha forests and whether the Big Bang was a cosmic fart from a celestial giant. We explore quantum biology and the role that quantum mechanics plays in biological processes? What will be the next big breakthrough? Are we going to keep discovering smaller and smaller particles? And finally, is everything just physics? You might be able to guess our answer…

Thanks to our Patrons aziz astrophysics, Scott Barnett, Christopher Saal, David Rhoades, and Jenna Biancavilla for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can watch or listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

About the prints that flank Neil in this video:

“Black Swan” & “White Swan” limited edition serigraph prints by Coast Salish artist Jane Kwatleematt Marston. For more information about this artist and her work, visit Inuit Gallery of Vancouver.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTWelcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk, Neil deGrasse Tyson here, your personal astrophysicist, and today we’re doing a Cosmic Queries edition.

Always a fan favorite, and I’ve got a co-host with me, Negin Farsad.

Negin, welcome back to StarTalk.

Oh my God, I love being back.

This feels so right.

The universe always feels right.

Let me just put it that way.

True.

Just to say.

So we have a guest, a friend and a colleague who in fall 2022 published a book called The Biggest Ideas in the Universe, Space, Time and Motion.

Now, you know, my people publish books like that.

Only my people can put titles on books.

We got this, Negin.

So let me welcome back Sean Carroll.

Sean, welcome back to StarTalk.

Thanks very much, Neil.

It’s good to have a personal astrophysicist around.

I have some problems that I want to send you when we’re done.

No, if you have a problem with them, I’d…

I don’t know what I can do for you on this.

So, we have notes here on you.

We call you a physicist, but also a philosopher.

And recently, you hail from Johns Hopkins University and the Santa Fe Institute.

And so, is the philosopher side of you that which is aligned with the Santa Fe Institute?

Because there’s some deep thinkers about some weird stuff over at Santa Fe.

There are, but they’re not aligned.

The Santa Fe Institute is a wonderful place.

It’s a research institute devoted to studying complexity, complex systems, from physics to biology to economics and the internet.

But they’re actually a little bit suspicious.

Well, just to be clear, Sean, just settle for us once and for all the difference between complex and complicated.

That’s a very good question and nobody knows the answer.

So I’m not going to settle for it once and for all.

One of the refrains at Santa Fe is just don’t ask us what complexity is.

We’ll tell you things about it, but the goal is not to find the once and for all definition of it.

Got it, got it.

I think there’s an easy comedian’s rule about that, which is just like if there’s more than three things that you have to understand, it’s complex.

In the joke, I got it.

And then she needed like a higher IQ audience to deliver it to you.

Yeah, I only perform for Mensa.

So that’s where I am.

So you’re also, Sean, you’re also host of the podcast Mindscape.

I love that title.

And just to settle it once and for all, you are the physicist, Sean Carroll, not the biologist, Sean Carroll, correct?

I am, although if people are interested, there is an episode of Mindscape where I interviewed the biologist, Sean Carroll, my evil twin with the beard.

That would be way too confusing for me.

It was, the transcription people had troubles, but that’s okay.

That’s officially complex right there.

So this book, what was, you’ve written several books, right?

And so what compelled you to land here in space, time and motion?

We had a little thing called the pandemic.

Oh, I heard of that.

Everyone had their pandemic projects, right?

And so my project was I made a series of videos where they were explaining physics to people, because that’s something that I know about, that might be useful, but of course it’s also been done before.

So the gimmick I had was that I actually showed you the equations.

I did not hide the equations from people.

And I taught you the math.

It wasn’t that you were supposed to be an expert already.

So I taught people calculus, derivatives, integrals, complex numbers, and then we learned all the equations of physics.

And so now I’m turning it into a book.

So Negin, do you hear what he said?

Just to be clear, he said, he taught you the math.

It didn’t mean you learned the math.

Two different actions.

See, he’s being precise in his communication.

I taught the math, right?

That’s the idea.

Negin, you would love this book.

If you don’t already know the math, this is your chance.

Are we talking, is it just like a basic edition, maybe some long-form division or?

No, it’s way more than that, but you get taught it and then you learn it and it’s great.

You’re a different person afterward.

Well, the rumor has it, and actually it wasn’t just rumor, I heard it from the person who said it, that the original editor for Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time, this was at Cambridge Press, warned him that for every equation he put in that book, the available audience to him would be cut in half.

Right.

So two equations is one fourth.

Three equations is one eighth.

And he nonetheless put in equations.

In fact, they didn’t even sign the book.

It went to another publisher and it became the biggest selling science book of all time.

So Sean, maybe you’re in really excellent tradition here.

I have a hundred equations.

So if they all cut my audience in half, the audience will be very, very tiny indeed.

You can do the math.

It’s not promising.

Two to the hundredth power.

I’m going to do that right now.

It means just Neil read it.

That’s the reader of your book.

A little tiny electron inside of Neil might have read it.

But my calculator is not working here.

So tell me, space, time, and motion, these are fundamental concepts in physics.

I don’t know how much we would know of the universe if we didn’t know those three very well.

So do you have any special insights you want to share before we go to Q&A?

Well, the basic idea is that we took the series of videos I did which covered a lot of material and we chopped them up into three books.

So this is the first book of a trilogy, which as I like to say is a format that works well for the Lord of the Rings and other famous franchises.

So this is the Fellowship of Physics.

And it’s basically classical physics, right?

It’s the physics before quantum mechanics came along.

But that still takes us very far.

By the end of the book, you’ve learned Einstein’s equation of general relativity and you look at the Schwarzschild metric for black holes and you know why there are black holes.

It’s a different level of understanding than you would get if you just looked at words and metaphors in pictures.

Okay, excellent.

So it’s a unique pedagogical addition to what’s otherwise on the shelf.

That’s the idea.

That’s always important.

That’s right.

Okay.

So I did 2 to the 100th power and I got a one with 30 zeros.

Why did you do that?

It’s a very big number.

Yeah, so it’s that fraction of the total humans who have ever been born.

It’s less than one person would understand what was in there.

Fractional Neil.

Again, that should be the tagline for your book.

So, Negin, you have your stash of questions there?

I do.

And this first one comes from Dylan in Flagstaff.

Dylan asks, as someone who is studying physics and astrophysics, what would it mean to discover what comprises dark matter and dark energy?

What could we then do and how would that drive future discoveries of our unknown universe?

I love that.

Sean, where do you sit on that?

Yeah, I mean, dark matter and dark energy, we have very, very good reasons to believe that they exist.

We know how much of them there are.

We even know more or less where they are.

We don’t know exactly what they are.

We know some features of them.

There’s a very leading candidate for dark energy, which is just the energy of empty space itself, what Einstein called the cosmological constant.

The dark matter, much less of a clear idea of what it could be.

Many, many good ideas of what it might be, but we don’t know which one.

And when we do discover which one, which I’m very optimistic that we’re going to do, we’ll be able to do essentially nothing with it to answer the question.

It’s not going to lead to a better warp drive or electric vehicles or anything like that.

No, I do.

I do kind of know that.

Because it’s dark, which means it doesn’t interact with electricity or magnetism.

So that’s why it’s so hard to find it.

We can’t touch it.

We have to use like the weak interactions of particle physics or something else super duper clever, even just to locate one particle of dark matter.

And to do that you need a giant experiment.

It doesn’t even touch itself, right?

So we can’t go around looking for dark matter planets or stars.

Is that a fair?

I don’t know, but yes, the simplest idea is it doesn’t interact with itself at all.

Maybe it interacts a little bit and that’s a very active area of research.

I did write a paper once on could there be dark photons?

Could there be dark light?

In other words, could there be a kind of light that interacts with dark matter particles but not with visible matter particles?

And interestingly, the answer is yes, there could be.

And then you could get like dark magnetic fields, maybe even dark atoms, who knows?

I feel like dark therapy needs, dark matter needs a little therapy to get in touch with itself.

You know what I mean?

And dark therapy needs a little matter.

I saw some comic where it’s somewhere and it says they discovered a new kind of particle.

And they had a dark matter and this other kind of matter and this is called doesn’t matter.

That’s a new kind of particle.

It doesn’t matter at all what it is.

But plus Sean, you have to admit, you sounded like you’re just making stuff up when you said, oh, we had to explain dark energy.

So the vacuum of space has energy.

There it is.

That’s your dark, that sounded very kludgy.

I just want to put it out there.

Well, I will recommend that people who think it’s kludgy on making things up buy a book that I recently wrote that explains how general relativity works, among other things, and I mean, that’s a joke, but it’s also kind of true.

I mean, this is one of the things about trying to explain physics, as you know, using metaphors and analogies and stories that it makes some things become clear and other things remain murky until you look at the equations.

And so like, if you know the equations of general relativity, the idea that empty space has energy is just like the most obvious simple thing in the world.

It’s a surprise we haven’t found it long ago.

Cool, cool, because it’s part of the equations.

It’s part of the equations, yeah.

Einstein invented it almost the year after general relativity itself, so it was not that hard.

I love how the implication there is like, even an idiot like Einstein discovered it.

Didn’t take him that long.

A year after, I mean, what a dum-dum.

Okay, well, let’s hear another question.

Dade from Milwaukee asks, what unanswered questions keep you up at night?

There’s an obvious one that keeps everyone up at night, I think, which is how to reconcile gravity with quantum mechanics.

I think that’s the one that keeps most people from sleeping.

Most people, for sure.

Negin, you didn’t get to sleep till three in the morning this morning.

It’s like that and like, who’s gonna be the breakout star of Real Housewives of Atlanta?

Those are the two main things that just I keep it.

Similar questions.

I heard them talking about it on Real Housewives.

So I think that they’re interested.

Cause they know that these are the two great triumphant discoveries of 20th century physics, right?

Quantum mechanics, discovering how atoms and particles behave, general relativity, Einstein’s theory of gravity, which tells us about black holes in the Big Bang.

But they’re incompatible with each other at a deep level.

And so people have been trying for decades now, some pretty smart cookies to make a single theory that unifies them together.

And we don’t think we’re quite there yet.

So let me be a little bit of a devil’s advocate here.

Just because they’re not compatible at certain ways that you might want to intersect them, why do you require that the Universe has an understanding that we have yet to achieve that makes them compatible?

Why can’t we just have a Universe?

We have two completely perfect theories of the Universe and they’re just not compatible.

So you have a philosophical prior here where you want things to be elegant and beautiful and maybe they’re just not.

Sure, things might not be elegant and beautiful, but things do make sense.

Things happen one way or the other.

Quantum mechanics says that something like a spinning particle can be in a superposition of two different states, spinning clockwise and spinning counterclockwise.

And that’s all fine.

And we understand what’s going on.

Schrodinger’s cat, if you’ve known that, it’s a superposition of a cat being alive and a cat being dead.

So take the Earth and imagine, just in your thought experiment capabilities, imagine a superposition of the Earth being here and the Earth being somewhere else.

That needs to have a gravitational field.

What is it?

Is it pointing in one direction or the other or in between?

There has to be an answer to that question and we don’t know it yet.

By the way, there’s a movie called Another Earth where there’s an Earth and then another Earth.

Is that what the title means?

Just really wanted to break that down for you because I know that’s a really complex title.

That’s Britt Marley’s story.

Yeah, exactly.

A sci-fi author and producer and actress.

I was actually on the jury for a prize at the Sundance Film Festival where we gave a prize to another Earth.

The Sloan Movie Prize, which is given to a movie that has something to do with science.

And so we gave them the prize.

This was a good movie.

We kind of worried whether it had anything to do with science or not.

But then we asked them afterward, what was your inspiration for this another Earth idea?

And they said, we heard a radio interview with Brian Greene talking about the multiverse and we got the idea from that.

So it actually paid off.

It had enough science in it.

I mean, it was very science fiction-y, but there was enough science given special attention that I thought I’d give it two thumbs up for sure.

So all right, Negin, keep them coming.

I also love that this is the panel of three nerds that saw that movie, Another Earth, which was not a huge mainstream blockbuster hit.

I just want to point that out.

We’re talking about a festival film here.

Okay, so Kevin the Somalier asks, does the conservation of energy go out the window in relation to the expanding universe?

Where is the extra energy coming from?

Actually, we got to take a quick break.

Wait, we got to take a quick break.

When we come back, we’re going to find out what Sean Carroll is doing with the energy in the expanding universe when StarTalk returns.

I’m Joel Cherico, and I make pottery.

You can see my pottery on my website, cosmicmugs.com.

Cosmic Mugs, art that lets you taste the universe every day.

And I support StarTalk on Patreon.

This is StarTalk with Neil deGrasse Tyson.

We’re back, StarTalk, Cosmic Prairies edition, with my friend and colleague, Sean Carroll.

He’s got a new book out, which has the audacious title, the kind of title that only my people can dare.

The Biggest Ideas in the Universe, Space, Time and Motion.

Congratulations on this, your next book, published with Dutton, Dutton Press.

So we got Negin, Negin.

We left off with a question, dangling.

We want to find out what Sean Carroll does with all this energy, where does he get it from that’s forcing an accelerating universe to expand?

And who was the one who asked that question?

That’s right, Kevin the Somalier asked about the…

Kevin the Somalier.

He’s going to tell us he’s a Somalier and not also tell us what he’s drinking, you know?

Next time entry is here, he’s going to tell us what his latest cool wine is so that we can all go out and buy it, okay?

Exactly.

He’s asking if the conservation of energy goes out the window in relation to the expanding universe and where does the extra energy come from?

Yeah, Sean.

And let’s take that with the dark energy side of this.

Well, you know, one of my minor claims to fame is that if you Google energy is not conserved, the first hit is a blog post I wrote explaining why energy is not conserved in an expanding universe.

But it’s not that, you know, all hell has broken loose.

What’s happening is that as space time itself is changing, it can sort of sap energy out of matter and particles or give energy back to the matter and particles.

So if you forget about dark energy, that sounds like weird and mysterious.

But if you just have a universe made of photons, the photons lose energy as the universe expands.

They redshift away.

So the total amount of energy in the photons goes down.

Now if you have dark energy, dark energy…

Wait, wait, they don’t want fairness to the photons.

I do want to be fair to the photons.

You want to be…

There’s a lot more of them than there are of me.

Fair to the photons.

So, the energy density is going down.

Yeah.

But the…

No.

Isn’t there some number?

Don’t do it, Neil.

Don’t do it.

It’s not conserved.

I guess not.

It’s really not.

Yeah.

But is it doing work on the expanding universe?

I mean, what’s…

Well, keep going.

I’ll interrupt.

Like I said, it’s not that energy conservation is thrown out the window, but it’s moved to a different room in your house, one in which it’s not as simple as just saying energy is conserved.

There is a new rule in general relativity that relates what is happening in space-time to what is happening with the energy.

New rules.

Did anyone see that coming from the classical era of conservation of matter and energy?

You know, energy conservation turns out to be a more slippery concept than you might think.

Again, this is something with the general relativity stuff that is just perfectly clear from the equations.

There is no problem with that.

But there is a similar thing in quantum mechanics where, you know, you measure a system and its state changes.

And the energy of the state can also change.

And people have not appreciated until recently that that means that, yeah, energy is not exactly conserved to an observer in quantum mechanics either.

So, you got to keep your what’s about you in this physics stuff, you know.

You can’t just rely on old faithful sayings.

And I think we used to always think of energy as a sort of like buttoned up, like uptight guy who just never strayed from the rules.

But that our conception of that was wrong.

He’s more like the leather jacket, the motorcycle, and he’s breaking hearts along the way by abandoning rules.

Yeah.

I wonder where does that analogy, where would that analogy fail in every analogy has a part that works and a part that doesn’t.

I think you don’t want energy to be your boyfriend.

I think that’s mostly a dating podcast.

So that relationship advice is very important.

So you want to date energy, but you don’t want to get married to it.

It’s not reliable.

Negin, we got that solved.

It fluctuates.

Next one.

What do you have, Negin?

All right.

So our next question from Chris Hampton, if you could shrink enough to stand on an electron, how much would time dilate relative to standard time?

How big would the atom’s nucleus seem and how far away would other atoms be?

I’m going to give like a really set of disappointing answers to these questions.

These are good questions.

But just so everyone knows, you can’t shrink down to stand on an electron.

That’s not something you can do.

I don’t believe every Marvel movie you see.

I know you didn’t think that, but okay, just verifying.

But the other thing is, remember again, quantum mechanics comes into the game.

We have this picture in our minds of the atom like a little solar system, right?

Like there’s the nucleus at the middle and there’s electrons orbiting around it like planets.

It’s not actually like that.

You’ve been lied to by that little cartoon picture.

The real electron is a fuzzy cloud of probability.

So it’s not just that you can’t shrink down small enough to stand on it.

There’s nothing there to stand on.

There’s no such thing as the size of the electron.

So, the rules of the game, the rules of existence, the rules of getting by from moment to moment are so incredibly different if you’re the size of an atom that we would have to start from scratch to figure out what was going on.

By the way, I took my child to a Disney exhibit this weekend where you walked into these rooms where they did shrink you down.

And because then we walked into rooms where popcorn were really, really huge and like you had to lift them with both hands.

So I just want to say…

It’s possible you didn’t actually shrink.

You weren’t at this exhibit.

It felt very real to me.

Disney has powers over the space-time continuum.

All right.

And something you just slipped by in your comment, Sean, but I think it bears some reflection.

We do not have any knowledge of the actual size of the electron.

Yeah, I think that it’s an important point.

The way that I would say it is there is no such thing as the size of an electron.

The electron is not like a little pea, but smaller, okay?

It’s a different kind of thing.

It’s intrinsically quantum.

And you don’t bump into those kinds of things in your everyday life.

Right.

But you can say that the proton is a thing, right?

Proton is more thing-like than an electron, but it’s a continuum.

There’s official vocabulary here, Negin, so I hope you’re taking notes.

More thing-like.

It’s more thing-like.

Yes.

More object-like.

Object.

Yeah.

Cool.

All right.

I do have to say, I feel like you’re totally just unseating all of the imagery, everything.

Everything I knew, the rules.

How does that make you feel?

This is just life.

You grow up, you go to school, you learn things that are all lies, and you learn the truth on StarTalk Radio.

That’s the progression of an intellectual.

Right.

That’s the standard trajectory for people.

Oh, here’s a question from David Smith.

David writes, it’s been proposed that every time a quantum event occurs that can have more than one possible outcome, that all possible outcomes occur and an observer only sees one.

Does an event occurring actually create the different results?

And where would the energy come from to create these alternate particles?

And is it a split in the universe as we’re so commonly described in sci fi?

People are really worried about the energy stuff today, aren’t they?

Like, is there something about like the heat wave that is making people afraid that their energy is not going to be up to the task?

But yes, this is exactly a leading way of thinking about quantum mechanics that you say, okay, there’s an electron and it’s in a superposition of spinning clockwise and counterclockwise.

But then the fact is, when you look at it and measure its spin, you never see both of them.

You see one or the other.

And there’s a leading theory says that that’s because there is a world, a parallel universe where there’s the electron spinning clockwise and you saw it spinning clockwise and a separate distinct universe where the electron was spinning counterclockwise and that’s what you saw.

In fact, this is more or less the straightforward prediction of the equations that we’ve been lovingly describing here.

And I wrote a whole other book.

My previous book was called Something Deeply Hidden, describing and defending exactly that point of view.

So I am someone who actually does think that is really what happens.

Not everyone agrees yet, but eventually I am going to place in the minds of the youth.

He is sure that is where he is headed.

Yeah, I know what is going to happen.

I know which way the wind is following.

But Sean, that means I am duplicated as well in that other observation.

No, you are the only one who is not.

It is everyone else.

There is only room for one Neil deGrasse Tyson in the multiverse.

Special dispensation.

Thank you.

Well, David actually has like an addendum that kind of a crescendo to his question, which is, what are the ramifications for our ability or lack thereof to change any events in our lives?

And in simple terms, is free will precluded by the very nature of existence?

You will not be surprised.

Answer that in two sentences, Sean.

Yeah, this is a nice one.

I was just giving you a softball.

Two sentences are, it has absolutely nothing to do with free will because what matters for free will is not whether the laws of physics are stochastic or deterministic, but rather there are laws of physics at all.

I guess I only need one sentence.

Sorry.

Well, I need a supplement to that.

Okay, keep going.

Well, it depends on what you mean by free will, right?

If you think that free will is somehow an ability of human beings to not be guided by the laws of physics, then you were in trouble long before quantum mechanics came along.

I don’t think that quantum mechanics is very relevant here.

All quantum mechanics says is we can’t exactly predict what the outcome will be.

But there’s still laws that say what the relative probabilities are.

So I really don’t think that quantum mechanics conflicts or helps free will in any way.

That’s a separate philosophical problem.

Could it be?

Well, philosophy is one of the tag lines of your profile.

So could it be that what we perceive as free will is some version of the probability space that quantum mechanics grants its particles?

Well, I would say that’s almost exactly true, but you don’t even need quantum mechanics to say it.

You could just say it classically.

You don’t know the position and the velocity of every molecule and atom in your body.

So when we talk about human beings, this is what is called the compatibilist view of free will, which is the most common one among philosophers.

When we talk about human beings, of course we talk in a language of probabilities and choices and volition and willpower, because we are not perfect calculating machines that can say exactly what’s going to happen.

So it makes perfect sense to talk about the free will that people have, not because they’re able to overcome the laws of physics, but because that’s the best way we have of describing them in the real world.

Okay, so our perception of what’s going on is completely compatible with the idea that we have free will.

Another way to think about that.

All right.

Well, let’s look at a question from Kira Lesser.

Kira writes, first of all, I’m very excited to read your book, Dr.

Carroll, can you explain what theory or theories in physics imply we don’t have free will and why do we really know enough to say that?

So you were sort of getting at this.

Yeah, there are some folks out there, you know, and you’ve read them, that are telling you that we don’t have free will.

We’re on the Sean Carroll camp here, so we get to side with you, no matter what you say.

So of course, we do believe in the laws of physics, okay?

There’s this thing called this idea called libertarian free will, which has nothing to do with political positions or economics, okay?

So don’t be afraid about that.

It’s just the idea that somehow the laws of physics don’t apply to human beings.

Now let’s say that we don’t believe that because we’re well-trained natural scientists, and we think that we are made of atoms, and we do obey the laws of physics.

That’s not enough to say therefore we don’t have free will, but it depends on what you mean by free will.

To me, what free will means is when I talk about a human being, I say this is a person who has opinions, who uses reason and thinking to reach conclusions.

Not correctly all the time.

But they use it.

A human being who uses reason, you know, that’s pushing it there, Sean, you know.

Maybe my best friends use reason sometimes.

But I can try to persuade them.

I mean, this is the hilarious thing about people who don’t believe in free will.

They’re constantly trying to make you change your mind.

And why would they do that if they didn’t think you had free will?

Yeah, the people who are certain you don’t have free will are struggling to get people who believe we have free will to believe them.

But they’re exercising their free will to not believe them.

This is actually my relationship with my toddler, basically.

That will make you crazy.

Like I’m telling her to do one thing.

She’s sort of like, no, do this other thing.

I don’t believe in your authority.

I don’t believe in any authority.

And then she, like, you know, vomits up some milk.

And it’s a very confusing situation.

And I feel like it’s exactly the dynamic you’re talking about.

I think it’s a promising political philosophy that she’s developing.

Solves, undoes a lot of puzzles, yeah.

Yeah, imagine if at the heat of argument, you just vomited up the milk you just drank.

You know, in the United Nations or in the halls of Congress.

You kind of win arguments that way.

I think that’s what happens.

All right, keep them coming.

All right, Pablo Duarte from Valencia, Spain, asks, scientists have been struggling…

Does it end in an E?

Is it Duarte?

You know, he wrote the pronunciation as do-art.

So I’m…

Oh, well, then there’s no E at the end.

So just do-art.

I wanted to say Duarte.

I did.

I did want to say that, but I didn’t.

Pablo Duarte from Valencia, Spain says, scientists have been struggling for decades to come up with this theory of everything.

Do you think we can get there with incremental steps, further developing existing theories, or do we need to wait for the next Newton or Einstein to come up with a new and innovative approach?

I love that question.

Yeah, this is kind of for everything.

Like, do we need a big, huge thing, or can we do it in steps?

We’re waiting for that person to be born, yeah.

I think that we will get there.

I see absolutely no reason to think that human beings are not up to the task of fully understanding the universe.

In fact, I would flip it the other way around.

I mean, we’ve made amazing progress in understanding the universe.

100 years ago, we didn’t know that there were other galaxies, much less the Big Bang or anything like that, and just look at how much we’ve learned in just 100 years, which is nothing, historically speaking.

So I think we will get there.

Will it require a Newton or an Einstein?

Well, guess what?

There’s a lot of smart people out there.

Someone’s going to get it, and then we will label them after the fact just as smart as Newton and Einstein.

So it’s not a matter of waiting for someone smart enough to do it, just a matter of the right place, right time, right person who will put the final touches on the puzzle.

Excellent, excellent.

We’ve got to take a quick break before we go to our third and final segment.

We’re here with my friend and colleague, Sean Carroll, and the one and only Negin Farsad, my guest co-host on StarTalk Cosmic Variety.

We’re back, StarTalk, Cosmic Queries Edition.

Sean Carroll’s got a new book on the biggest questions of the universe, and he’s tackling space, time, and motion.

Some of the fundamental things that give physics is life force.

And I’ve got Negin Farsad.

Negin, you’re a host of Fake the Nation, so you got your own podcast.

I’m a host of Fake the Nation, of which you have also been a guest a couple of times.

And you’re also a regular on NPR’s Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me.

That’s a fine piece of work right there.

I am, and it’s a really fun show.

And then the other thing I wanted the listeners to know is that I’m on the new Hillary Clinton show called Gutsy.

It’s gonna be available on Apple TV in the fall, whatever this podcast drops.

I think all the episodes will be available.

And so you get to see me and Hills, because we’re close now, chat about ways of defeating the haters out there in America.

All right.

And you have a toddler running around the house.

Yes, just vomiting milk.

One of the haters.

Right, one of the haters.

She must be defeated.

So, all right, so you got some more questions for Sean.

So we have from Avneesh Joshi from Houston, Texas.

They write, I am 11 years old.

I watched a show on Netflix, which also featured Dr.

Tyson.

One of the astrophysicists mentioned, I mean, is this right?

One of the astrophysicists mentioned Lehman alphablobs.

What exactly are they and what makes them so special?

I can handle this, Sean, unless you want to jump in on it.

I want to let you do it because you’re an actual astrophysicist.

It’s very astrophysics, that question.

Where the universe came from is my idea.

Yeah, so he made the earth and I’m just a forest on the earth in my reply to this question.

So what we learned, I guess, a few decades ago, in the 1980s, early 90s, we learned that the universe doesn’t only have galaxies in it.

There are these blobs of hydrogen clouds that are highly populated in the voids of space.

And you don’t otherwise see them because they’re not making stars actively the way regular galaxies do.

But for other galaxies quasars far away, their light is trying to reach you.

And in order to get to you, that light ends up piercing through these blobs of hydrogen clouds.

And for every one of these it pierces through, it leaves its signature in the spectrum that you see.

And there’s tons of them in every spectrum of a very distant galaxy.

And it’s a feature, it’s behavior of the hydrogen atom, Lyman alpha, it’s a feature that you can measure in the spectrum.

And there’s so many of these features, it’s called the Lyman alpha forest.

And so that’s what that is.

That was pretty good, you did a good job there, Neil.

Oh, thank you, Sean.

I’ll let you come back.

And maybe I’ll be a guest on Negin’s podcast.

I didn’t go that far.

Yeah, okay, yeah, hold up, all right.

Okay, so next one.

Well, I’m gonna take things down up a notch here and just get real serious by sharing a question from David Rhodes.

David writes, could the Big Bang just be a cosmic fart from a celestial giant?

I love it, because whenever physics questions start with, could it be possible that, the answer is always sure.

I mean, I don’t know if that’s the way to go through your life thinking that that’s what the Big Bang was.

Just to be pop culture fluent here, there’s an episode of Family Guy where that is demonstrated.

Where a cosmic fart is demonstrated?

There’s a deity that farts out our universe in the Big Bang.

That’s an episode of Family Guy, just to be clear on that.

But okay.

We would have to attach some equations to the idea and make some prediction for the abundance of light elements from the early universe.

I can imagine testing this empirically.

Probably there’s more methane in a fart than there was in the early universe, so it might be falsified, I’m not sure.

Oh, very, I’d like that, that’s right, because typical farts are high methane.

And methane is carbon and hydrogen, and there wasn’t much carbon in the very early universe.

A typical fart is high methane, but a cosmic fart.

Again, true.

You know what I mean?

That’s a loophole, yeah, you got that one.

Negin, you could easily have been referee number two on this paper that we’re writing.

I might as well slip it in here.

There was a conversation I had with Chuck Nice and we were talking about the powers of Superman and someone asked, would Superman eat super food?

Does he have a super digestive track?

And we just followed that through.

If Superman is super in every way, superhuman in every way, he would have a super digestive track, which might mean he would have super farts.

And then we thought if he has a super fart, which is high in methane, he could ignite it with his x-ray vision and then have a flamethrower out his butt.

Yes, yes.

So as Sean had intoned there, it is possible to pursue questions such as that and see where they take you in a serious way, even if they’re asked with tongue in cheek.

I’m not sure if I like this dark and gritty reboot of Superman that you’re proposing here.

But a flamethrower, he uses breath to freeze things.

He needs something to burn things, so there it is.

Who is his gastroenterologist in that situation?

But Chuck lost a gastroenterologist.

He imagined, because he has to roll down his drawers and then stick his butt out and then make that happen.

Oh yeah, it gets a little salacious in front of the kids that he’s trying to save from harm or whatever.

Okay, so Negin, see if you can salvage this conversation back to…

Well, you know what?

I’m going to turn to Zachary Kean from Nebraska who was wondering, since Dr.

Carroll has an interest in quantum mechanics, if he’s ever heard of quantum biology and his thoughts on the idea that quantum mechanics could play a role in the biological processes of animals.

Oh yeah, when I wrote my book on quantum mechanics, one of the bits of research I did was to go to Amazon and type in the word quantum into the search bar, looking for what books have been written with quantum in the title.

And so there is quantum yoga and quantum leadership and quantum healing and quantum prayer and most of these…

Quantum leap.

Don’t forget quantum leap.

Quantum leap.

The Schrodinger equation appears in almost none of these books as far as I can tell.

But quantum biology is very different because quantum biology actually does exist.

You know, in one sense, everything is quantum.

You and I are quantum.

The table in front of me is quantum.

But the quantumness of it doesn’t show up very obviously.

The classical physics way of thinking about it is good enough for most purposes.

So in quantum biology, you try to pinpoint areas where processes happen that would have been impossible in good old Newtonian classical physics.

And so it’s thought, for example, that the way that energy is transferred after photosynthesis, you know, energy goes from the leaf of the plant into its innards.

And the way that it gets there requires quantum mechanics to understand.

It sort of takes different channels all at once in a superposition.

So I think that’s very interesting and exciting.

I’m not an expert in it myself, but the world is quantum, so why shouldn’t biology be?

But that’s describing the chemistry of the process, right?

So there is no understanding of biology without chemistry.

There’s no understanding of chemistry without physics.

So isn’t it all just physics in the end?

Yep.

Everyone should learn physics and apply it to make the world a perfect utopia.

See?

I hate to make the subtext text there, but sometimes you just have to be explicit.

All right.

Let’s keep going.

Negin, we’re making good progress here.

We’re really plowing through these.

Here we go.

Conner Holm asks, Dr.

Carroll, what do you find to be the most fascinating thing in the universe, either observed or theorized?

And what do you think or hope will be the next big breakthrough in theoretical physics?

Love it.

I mean, you’re asking me to choose the most fascinating thing in the universe.

It’s like asking which one is your favorite child, right?

You know, like I love everything in the universe equally, but I do have a…

And Mrs.

Perry says that, and it’s not true.

It’s not true.

It’s not true.

You could totally pick a child online if you have to.

Parents have to say it.

Right.

They have to say it.

I have a soft spot for what we actually just talked about at the intellectual high point of the conversation, which is that there is a moment in the history of the early universe where the early universe is like a nuclear fusion reactor.

It’s turning hydrogen into helium and other elements by fusing them together.

That’s pretty cool all by itself, but it’s not that different than what happens at the middle of the sun.

What’s interesting about it to me, which will never stop blowing my mind, is that this happens a matter of seconds after the Big Bang.

We live in a universe that’s almost 14 billion years old.

A few seconds after the Big Bang, nuclear fusion was going on.

We take the theories of physics that were developed by us here on Earth with our tiny little brains in the past 100 years and we extrapolate them back to seconds after the Big Bang to make a prediction for how much helium there should be and how much lithium and all that stuff.

It’s exactly spot on.

We get it right.

Human beings are able to use the power of physics to understand what was going on a minute after the Big Bang and it agrees with the data and that just will never cease to amaze me.

Cool.

I don’t even know what to say to that, but except that it really does feel like a brag, like just a brag for humans.

Oh yeah.

Oh yeah.

What do you mean?

I mean, you said my favorite.

I’m not going to pick the thing that makes us look dumb.

There’s plenty of those.

Like, I don’t know, like American cheese.

That one makes us look dumb.

Yeah.

Like there’s a lot of, you know, but you have to take the good.

There’s got to be a lot of asterisks in there that includes all of the cheeses that we did wrong.

Negin, I’m just trying to think back.

Go to ancient France where they have their famous cheeses and say, one day there’ll be a country where they put cheese in a spray can.

That will bastardize this art.

Yeah.

I can just see future historians thinking about, you know, the list of accomplishments of the 20th and 21st century humanity and like, we have room for one more.

Should it be the Big Bang or cheese in a can?

Opinions differ.

Time for just like a couple more.

Here we go from Tony Thompson, he writes, we continue to break down matter further and further as we explore molecules to atoms, atoms to neutrons and protons, then to quarks, etc.

In theory, if we ever reach the most fundamental building blocks in the universe, would it be logically possible to prove it or will the search for smart particles or will the search for smaller particles always exist?

I love that.

I love that.

So let me restate that.

Sean, we have our base particles that were taught in physics.

What confidence do we have that they cannot be further broken apart?

Or we just like the Greeks who said the atom is indivisible and then we divide the atom and so the word doesn’t even make any sense anymore, though we still use it.

Yeah, it was the chemists in the 18th century who really caught on to the idea of atoms and they sort of leapt a little bit too quickly in assigning the word atom, which is the Greek word meaning indivisible, to their little building blocks of chemical elements because of course then we discovered that they are divisible, right, into electrons and nuclei.

The nuclei are divisible into protons and neutrons.

The protons and neutrons are divisible into quarks and gluons.

But the point is that by this point, by the time you get to the quarks and gluons, physicists are not complete dummies.

They caught on that this is a really good thing to do.

You could become famous if you figure out that the particles that we know about are made of tinier particles, right?

That’s a route to success.

So everyone asks this question and what you do is you do science.

You say if it were true that electrons and quarks and so forth are made of smaller particles, how would we know and can we build a theory in which that’s true?

And people have tried to build theories in which that’s true and they are constantly disproven by the data.

So you don’t ever in science prove that something is the final answer, but what you can do is disprove a whole bunch of other things and eventually you’re left with the remaining possibility.

So, I’m of the opinion that there need not be a very deep further set of layers of reality below what we currently know.

It could be a completely different kind of stuff, right?

It might not be new particles at all, but I don’t think we’re just going to continue to find smaller and smaller particles out of which the things we now know are made.

That’s very not Men in Black, you realize, right?

I need to have the talk about taking Hollywood movies as documentaries again, yes.

Are we a snow globe on the mantle of an alien, you know, our entire universe?

What that is.

So, Negin, I think we don’t have any time for more questions.

I’m sad.

Oh my gosh.

But let me find out.

Where can we find you, Negin, on social media?

Yes, you can find me at Negin Farsad, N-E-G-I-N-F-A-R-S-A-D on all of the things.

And I am even on TikTok, where I really, I do spare the people my dance moves.

And Sean, you got it.

You’re active in all spaces.

So where should we direct people first?

Multimedia.

The book that is out fall 2022, The Biggest Ideas in the Universe.

I think it’s a great way to dig a little bit more deeply into the ideas of physics than you usually get a chance to.

And then the podcast, Mindscape, where every week we talk about some big mind blowing ideas.

It’s a lot of fun.

And you have great videos that are all collected.

Are they in your own YouTube space?

There are videos.

You can just go to my website, which is preposterousuniverse.com.

You can find the blog, the podcast, the videos, the books, the whole shebang.

Excellent.

Excellent.

So, Sean, it’s been great to have you again.

And keep us in mind every time you do something cool, because we’re going to want to showcase it.

And Negin, good luck with the Hillary Show.

What’s it called again?

I call it the Hillary Show.

It’s called Gutsy.

That’s the Hillary Show.

The Hillary Show.

There it is.

We’ll be looking for that.

So excellent.

This has come to a close.

We’re landing the plane right now.

I’m Neil deGrasse Tyson.

You’re a personal astrophysicist.

And you’ve been listening to, possibly even watching, our Cosmic Queries edition with Sean Carroll.

As always, keep looking up.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron