Explore the intersection of science and morality when host Neil deGrasse Tyson answers fan questions with the help of guest Michael Shermer, the founder of Skeptic Magazine and author of The Moral Arc. Co-host Eugene Mirman has picked some of your deepest, most thought provoking questions to throw at Neil and Michael, like, “With evidence proving we’re all equally the same, why do racism and bigotry remain strong in certain groups?” Find out about the brain mechanism known as ‘one-trial learning,’ why we’re evolutionarily prone to pigeonholing, and why racism is actually the nefarious hijacking of an evolutionary force, tribalism. Can the scientific method be applied to political systems, society, and human behavior? Compare scientific discoveries that have shaped our morality, and contrast both the concepts of mutually assured destruction with supernatural beliefs that court death and the fears of terrorism with gun violence. What are the ethics and morality of cloning and bioengineering? Would clones have rights? Next, Neil, Michael and Eugene ponder whether aliens would be good or evil, and how we look at that question through the lens of human history filtered by imperialism and colonialism. You’ll learn about phrenology, the eugenics movement and repeated anti-immigration movements. It’s not all bad news, though: you’ll also hear about the Flynn Effect: data indicating that the general population is getting smarter and more scientifically literate, and why that might be.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. This is StarTalk, and I'm your host. You're a personal astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and I serve as the director of the...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk, and I'm your host.

You're a personal astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and I serve as the director of the Hayden Planetarium right here in New York City at the American Museum of Natural History.

And this edition of StarTalk is one what we call Cosmic Queries.

And we've solicited questions from our fan base and all the various social media on the topic of the role of science in the formation of our morality.

And I can't do that alone.

I could try it, but we got people who thought way more deeply on this than I have.

But before I get to our principal guest, let me just introduce my co-host, Eugene Mirman.

Eugene, hey.

Hey, welcome back to StarTalk.

And there's a man sitting to your right.

I know, I can see him.

So this is, of course, Michael Shermer.

If you don't know this guy, he's founder and editor-in-chief of Skeptic.

Skeptic Magazine.

It's a magazine.

I don't believe it.

See, I've never heard that one before.

And I've known your work forever, and I'm glad somebody's doing it.

Almost eternity, yes.

You're doing the good work.

You do all the hard work, and I get to just tell people to have fun with the universe.

Well, unfortunately, there's a lot of bunkum that needs debunking that we do, yes.

And so one of your recent books, because you've got a lot of, you come out with books all the time, so be a regular guest for each book, please.

And currently, it's called The Moral Arc.

Great title.

Great title.

Well, the title, of course, comes from Dr.

King's famous How Long, Not Long.

That's right, yes.

Not just a doctor named King.

He's the cardiologist that I really love.

But he had a moral arc, which is a good thing, because doctors are supposed to heal.

Actually, King got that from a 19th century abolitionist preacher named Theodore Parker, who first coined the idea that there's an arc to the moral universe and it's bending toward justice.

And he quoted that verbatim in his speech.

That's right, he did, yes.

Well, he had a whole bunch of religious tropes, and so often religion is credited with a lot of the civil rights movements.

But in fact, Dr.

King's primary guide was Gandhi.

That is nonviolent, peaceful protests and that sort of thing.

And that particular march from Selma to Montgomery, which is now the famous one, immortalized in film, was not just an accident.

They really shopped around to figure out where can we march that will get the most attention for our cause?

Who is the biggest racist we have, the biggest bigot in the South?

And this is Bull Connor in Alabama.

And so that-

Isn't that weird that there's like a portfolio of people to choose from?

Yeah, on a scale of one to 10, who is really a badass?

This is the guy we want.

This category over here, now which one is right?

So I hadn't paused to reflect on the fact that the entire civil rights movement is some steps towards morality in our species.

Absolutely, the idea that-

At least in the United States, of course.

Well, really worldwide, at least in the Western world, since the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, the idea that the universe is knowable.

Just to be clear, I would date that from like 1600 onward.

When we first start not only thinking about how the world must be, but testing the ideas and coming up with theories for how and why.

Exactly right, right.

So you can start wherever you want to start, Copernicus or slightly after Kepler.

But I really.

This would be 400, 500 years ago.

Yeah, so a big turning point though is Newton's Principia, which after that.

No, Newton's my man.

I know he's your man, that's why I brought him up.

Just watch what you say.

And he's not just your man, he was pretty much everybody's man.

I got his back, okay?

So just back up when it, all right, so.

You must get those letters and papers from alternative physics people that go, Newton was wrong and here's why.

Yeah, of course, of course.

And it's really.

I don't know about this at all, but I get it and we can move on.

Uh-huh.

You probably want to be comedians that send you material.

Yeah, that are like, Newton is wrong.

And I'm like, I don't think so, but.

Newton wasn't funny at all, but I am.

Well, you're right, he wasn't funny at all.

He's very serious.

Anyway, the idea was that the universe is knowable and it's governed by certain principles and laws that we can understand and even put into equations.

And after the Principia was published, everybody wanted to be the Newton in their field.

So Montesquieu wrote a book called The Spirit of the Laws, which was about what are the conditions by which people design certain laws and customs and economic systems and political systems.

There must be some governing laws behind that.

And then this eventually gave rise to the study of the economy as a knowable system.

The economy is governed by laws and principles, just like the universe is.

And so solar systems, ecosystems, economic systems.

And so this is what the Enlightenment was all about.

By the way, I still think that's a wishful thing for economists to analogize what they do to what physicists do in the universe.

And you know that there's some physics envy going on in there, you know this.

Well, of course, but actually you have a deeper point there that maybe it's not doable.

It may be sort of epistemologically, you can't ratchet up from a solar system to an economic system, maybe there's too many variables.

But that is what they try to do.

At least.

And people are the biggest variables.

It's good that they're trying.

I mean, we need a functioning society with an economy.

It's better than randomness.

Yeah, it's true, it's better than, yeah.

Chaos.

Yeah.

Like some economies.

Yeah, sounds like you guys are really mad at, you want bartering.

But once you ratchet up to say social systems and then moral systems, I mean, they actually talked about the moral sciences.

What's that?

Well, if human behavior is governed by certain laws and principles like animal behavior is, like planets are, then how we treat each other should be treated as a problem to be solved rather than a sin to be condemned.

So instead of religion condemning people for their bad acts, let's look at what they're doing, homicides, for example, killing each other.

What can we do to decrease the amount of that?

And that's what political systems began to experiment with.

Let's try this, let's try that.

So apparently-

Free hats.

That did it.

That did it.

All the violence.

And it's odd that the threat of going to prison apparently is not working, given the prison population.

Well, I think, yeah, threatening in general is often not the best way.

Well, the first book on that was by a guy named Cesare Beccaria, an Italian Enlightenment philosopher who wanted to be the Newton of his field, and his book was on how the punishment should fit the crime, his essay on crimes and punishments.

He's the first to articulate-

You know, I just acquired that book two weeks ago.

You did?

Yes.

Seriously?

Just, from an old antiquarian book.

You've been thinking about punishing?

I think I only learned that that book existed from reading some of what you've written.

That's right, yep.

And he tried to figure out how do you match a punishment to a crime?

Right.

And what do you go about to even establish that relationship?

Yeah, I was very impressed with what that was.

At the time, the death penalty was not only on the books, but it was on the books for over 220 different crimes.

Like if you stole someone's moccasins?

That's right, stealing moccasins.

Death penalty, off with your head.

Wow.

We're distressed about ISIS beheading people.

States used to behead people right and left or any.

You insult the king.

Insult the king's garden, and you could be beheaded.

Really?

His garden?

This king sounds like a real jerk or a control freak.

Oh, the gardens in the 17th century, 18th, were very regimented, and they were supposed to be very geometrical.

Well, the English gardens were.

The French gardens are more freeform, if I remember correctly.

But to insult them in either place was death penalty.

Death penalty, yeah.

Wow, that does seem a little extreme.

So Becker Rea's idea was.

Yeah, were they very nice gardens, or was it kind of like it would be?

Well, some of them were, but you know, come on.

Were they insultable?

Yeah, exactly, it's like, well, I don't know, maybe don't insult the man's garden.

Your rhubarb are not quite lined up straight, yeah, all right.

Off with his head.

Off with his rhubarb.

So the idea that it's the principle of proportionality, that punishment should fit the crime, and what a concept, and we would sort of take it for granted, and we often abuse it and then come back.

So the crime wave of the 60s and 70s is followed by the prison wave of the 90s and the 2000s, and now we recognize, okay, this has gone too far.

These severe punishers for a third strike of a half an ounce of pot.

Of anything.

Of anything, right.

Oregano, oh, okay, off with his head.

That's too far.

But the idea that we're gonna experiment with things, that's kind of a scientific idea.

Let's try this.

Maybe you just dangle someone upside down for an hour, and then they won't be criminals.

Have we tried that?

Actually, this is not a bad idea.

It's gonna shake up somebody's brain, if there's a criminal brain.

Anyway, but what we're after here is how we can apply the methods of science to a political system, society, human behavior.

Well, that's precisely how we pose the question to our fan base, knowing that you'd be with us in the studio here and now, visiting from Los Angeles.

You psychically knew I would be coming.

Yeah, it was just data, I'm not saying.

So Eugene, you have some of these questions.

Neither Michael nor I have seen these questions before.

You're popping them on us, so let's.

I've asked you questions that people have asked.

This is from a Patreon.

This is a Patreon patron, Mark Miller, and his question is, with evidence proving we are all equally the same, why do racism and bigotry remain strong in certain groups with strong ideologies?

He's from Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Right, wow, okay, whoo, that's the big question.

Yeah, he jumps right to the.

Well, okay, so first of all, one of the cognitive capacities we have is pigeonholing things.

We classify things, planets, animals, other people.

And unfortunately, we're very good at this.

There's good reasons to do that.

It's good to be able to realize that those mushrooms are good to eat and these are bad to eat, and you can tell the difference by the color of the skin of the mushroom.

You don't have to bite it and throw up or die.

And die, that's right, and it's good to get that.

But if you did, that would be immensely valuable to those who survived.

If they saw you, otherwise you're a dead guy by a bunch of mushrooms, who knows what happened.

And in fact, we have a brain mechanism that does just that, it's called one-trial learning.

If you eat a mushroom and vomit and become violently ill, you'll never want to eat that again.

And that applies to any food.

In my case, it was red wine when I was in college when I had way too much red wine.

And it took me about 10 years before I could drink red wine again, just because my brain was, okay, that made you vomit.

Don't eat that again.

Only gin.

Gin will keep you safe.

That's what you would tell yourself.

It happened to me with, I got, what's that really bad one you get in your lower digestive tract?

Well, there's Montezuma's Revenge.

Salmonella.

So I got salmonella.

Do you eat raw chicken with chicken tartare?

No, it was mayonnaise, likely.

And at the time, the taste in my mouth was orange soda.

And I went 10 years before I could get near orange soda.

What about mayonnaise?

You learned it wrong.

I didn't have the taste of mayonnaise in my mouth.

That's the difference.

That's the confounding of the accuracy of the data that you would use it as a cause and effect.

And in essence, that's what racism is.

It's just a hijacking of a system that's there for good reasons.

And then say, okay, all people that look like X, that's in the category of the bad stuff and we don't want to get near them.

You see this now with most of the ISIS terrorists is related to Islam, so therefore, we just lump into this big category.

That's just so predictable.

How much of it is just tribalism?

Well, that is what the, that is in part what tribalism is.

Although, see, tribalism is whoever is gonna be your kin and kind and the people you grew up with and hang around along with.

And share closer DNA.

And those are typically gonna be racially similar to you and so on.

So we naturally just look at people in other tribes unless there's some way to interact with them to reduce the amount of anxiety and increase trust.

Which is where pop music comes in.

Pop culture and pop music.

Music is actually one of the great unifiers.

You know, if you like Bono and I like Bono, or take your pick, you know then.

Okay, good.

So, you know, then we're less likely to, you know.

So maybe the real answer is to get ISIS some, well first of all you two.

And then probably from there just be like, well okay, maybe we can agree on Led Zeppelin.

Well that would be good.

That'd be a good start.

We're wired to be racist.

Yeah, yeah, so we're wired to be tribalist.

Now, is it possible to, for the tribalism to relate to your proximity to them rather than to what they look like in such a way that people in your city, however large, become your tribe?

That's right.

And the way that happens is through interactions of any kind.

Trade, just.

Yeah, so like, like, interstate trade reduces the likelihood of a conflict between two states by a significant percentage.

It reduces it by like 100%.

So.

By 100%?

Well, but it's a.

Sorry, I get those.

Yeah, yeah, actually, I misspoke, by 50%.

Oh, okay.

That's so much more believable now.

Coming the other way, it would go up 100%.

Yes, yes, yeah.

Going from 50 to 100, you've increased by 100%.

Yes.

But going from 100 down to 50, it's only 50%.

I mean, the Chinese are fairly different looking from us, but one reason not to go to war with them.

Is they make your iPad there.

And so, because they do that, we don't want to bomb them.

We want to buy their, we want to give them our money and they want to give us their products.

So there's a mutual exchange.

But that works with ideas or music or any kind of pop culture.

So it's a leftover evolutionary force.

As you said, I love the word you used, hijacked or co-opted for completely nefarious reasons.

That's right, but yeah, that's right.

So it's an evolutionary shortcoming in our species.

As Jared Diamond likes to point out from hanging out with Papua New Guineans, you know, indigenous peoples, if you run into a stranger on a hiking path, you should either try to kill him or run for it because he might try to kill you.

The idea of reaching out and shaking somebody's hand is just insane because in the ancestral world that we evolved in, that would have been suicidal to do that.

It's one of you had turmeric and the other had gold.

Yeah, that's right.

Yeah, so you make a swap or something.

So that's one of the reasons why anthropologists have documented like the potlatch where I'm going to throw a big party for you and you throw a big party for me.

It doesn't matter what it is.

We're exchanging something and that tells me I can trust this guy.

He gave me something.

I gave him something.

He trusts me.

I trust him.

And that breaks down the natural tribal barriers.

So the idea would be if we could expand it to the whole city.

So if we could have a worldwide party, let's call it Christmas and exclude only New Year's.

It's probably better.

New Year's is pretty good.

I mean, how much violence happens on New Year's?

I mean, think about it.

Well, probably, I don't know.

Probably less than on Christmas.

Way less.

And so in this, I've always been fascinated by the leftover evolutionary baggage we have simply to have us survive in the past that then would interfere with our survival.

Absolutely.

And you can turn it back on, unfortunately, and that's what groups like ISIS do.

They tribalize things and they're the enemy.

We're the good guys.

It's the, you know, that's sort of dividing people up into black and white, good and evil.

And it's easy to turn those things back on.

Fortunately, we're pretty good at turning it off just through all these different mechanisms that...

And so one of the things states have done by making their borders more porous, say, what's the chances of Germany and France going to war?

Are these scientific...

Very slim.

Adjectives.

Yeah.

Porosity.

That's good.

The gelatinous mass of the economy.

Stop talking about Greece like that.

But where, you know, for 500 years, the great powers of Europe were at war with each other pretty much every year.

It just stopped in 1945.

Until they started trading transistor radios and stuff.

Absolutely.

Yeah.

It's cheaper for the French and Germans to trade with one another and cross borders and so on.

Well, now with the EU, you don't even have to show your passport.

It's like going from here to Texas or...

No, wait, where are we?

Not here.

So, Eugene, a couple of minutes left.

Do we get it?

Can we slip in another question, do you think?

I think we can.

All right.

Here's one from George Isaac on Facebook.

Neil, how far do you want human space exploration to be by the year 2115?

So 100 years is what he's talking about.

So here's an interesting fact.

And to the point of your book, The Moral Arc, the International Space Station, which is a collaboration of various nations, including the United States and Russia, is the largest collaboration of nations outside of the waging of war.

Bigger than just trade in general?

Well, you talk about how many nations are involved and the value of that mission, how many billions of dollars it represents.

Yeah, I guess there's trade.

Okay.

You can interconnect economies.

I'll grant you that.

But they're not people working together in front of one another as it is in the space station.

Someone upon hearing that thought, well, maybe the World Cup is like that or the Olympics, but the cost of going to space exceeds this and the economic commitment is greater and there's no real private enterprise return on it.

So it's really nations just trying to cooperate.

And I'm fascinated by the possibility that maybe the best way to have the world cooperate is to put them all in one boat, basically, space boat, and now they got to treat each other right.

A common enemy in the form of an alien is a popular sci-fi story that unites all nations to fight against this evil enemy, something like that, but what would be more interesting is if we had a new society set up on Mars to see what kind of government would they come up with.

Just 10 guys and then there's 50 and then 100 and then 1,000, 10,000.

What would they do?

Well, Lord of the Flies for grown-ups.

When we come back, more of Cosmic Queries with Michael Sherman on Star Talk.

We're back on Star Talk.

Yeah, and our special guest today is Michael Shermer.

Hey.

And he's publisher, editor, grandpa of Skeptic Magazine.

And a director.

And a director.

And every time I turn around, you've got a book out, and The Moral Arc is your latest, I think.

Yep, that's right.

And I think I even blurbed this book.

You did.

You know, my goal is to be the shortest blurb on any book jacket.

Yours is the shortest.

Shermer's great, read this book.

No, I try to be a little cleverer than that.

Yes, no, you are.

Like your tweets, they're very thoughtful and clever.

I mean, not everybody does that.

Yeah, no, yeah, it's usually, they're self-serving, usually.

Yeah, the self-serving ones, the blurbs go on for like half the length of the book.

It's like, no, this is my book.

Right.

You just needed to say, this is very good, please buy this book.

So we're fielding inquiries from our fan base.

This is the Cosmic Queries edition of StarTalk, and we're fielding questions related to the role of science and the formation of a moral philosophy.

Because historically, that turf has been, at least in the popular belief, has been granted to religions as a source of moral code.

And so to come out with a book that takes another take on that, for some people that might be fighting words.

It is.

In my chapter four, Why Religion is Not the Major Driver of Moral Progress, it has raised a few hackles.

But, and let me say right off the bat, of course, religious people can be as good as anybody else.

And vice versa, atheists and secularists can be as good as religious people.

I'm not talking about individuals.

I'm talking about ideas that change the world.

So back to Newton, the Enlightenment, Adam Smith and Immanuel Kant and David Hume.

These are all skeptics, secularists.

And their idea was that, instead of arguing this is the way things should be because our religion says so, or our holy book says so, or our God says so.

Let's see if there's certain ideas that I can articulate and convince you by the power of the ideas alone.

And not by the power of the authority of a religious text.

That's right.

So the idea of rights, rights were invented in the Enlightenment, really the late 17th century, early 18th century, and then came to fruition around the late 18th century with the American and French revolutions.

The idea that just by dint of being human, you are born with these certain inalienable rights.

Now, there's certain arguments beneath that, natural rights, by nature, what does that mean?

Where, through the telescope or microscope, where do I see rights?

At some point, you have to-

It's written on the, you didn't look to the left of the-

Yeah, yeah, it's on the sky, clearly, right.

And that I can't just force you to accept my argument, I have to convince you.

Well, you could force them to accept your argument, but that isn't probably your intent.

Right, that's a different kind of government when you do that.

Exactly, yeah, yeah.

And so immediately, a lot of these Enlightenment thinkers we call them philosophers, today we would call them scientists.

I mean, they really had a grounding of-

We wouldn't call them bloggers.

They might have been bloggers.

David Hume, he's got the biggest Twitter following of all the social scientists.

I wonder how many Twitter followers the great philosophers would have had.

I think they might have been wordier than 140 characters.

But the idea is that, so we have a human nature, they recognize that we're born with certain characteristics, certain inner demons and better angels, and the idea is structuring society in a way to attenuate the inner demons and bring out the better angels.

How can we do that?

So certain laws, customs, economic systems, you know.

They help inform this trajectory.

That's right.

Yeah, one of the founders of economic science before Adam Smith was the.

Adam Smith's great work, The Wealth of Nations, 1776.

That's right.

But the real title of it is an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations.

It's a scientific treatise.

He was a professor of natural philosophy, but what we would call science.

And so he's looking for cause and effect relationships.

Okay, if supply goes down, what happens to demand?

You know, this is where we get these ideas.

Things move around like this.

So it's an exploration in the causes and effects of things.

Yeah.

Of everything, right?

Let's see what questions we've got coming for us.

So.

And we haven't seen these questions, and they're just from.

No.

And do we know the source?

We do.

We're gonna say the source.

Yes, please.

At RNStraw on Twitter says.

Asks.

He does ask, it's true, technically.

Hey guts, I think he means guys.

With that spell check.

Hey guys, what is the effect science has had morality on us as a race?

Have we become kinder or started to grow cold?

So let me shape that a little differently, because you've already addressed pieces of that.

There's scientific outlook that has informed people's attempts to arrive at a moral philosophy.

Are there any actual scientific discoveries you can point to and say, that discovery will shape this current or future morality?

Well, I think there's certain things, like certain technologies are somewhat neutral, say the atomic weapon or something like that, that can be used for and against.

But just the...

You mean for good or evil?

That's right.

But just the improvement of the general conditions of humanity I think helps.

Just like the technologies of the internet that expands our moral sphere to consider other people as just members of our honorary family or our honorary group, even if I don't see them.

That technology I think helps.

I mean, one of the ways of tricking the brain into thinking of a complete stranger as an honorary friend or family member is what nonprofits do when they want you to adopt a child.

You've seen those late night commercials adopt this.

I've done this.

And studies show that if you show people a picture of like a hundred starving kids in Kenya, they'll give X amount of dollars.

If you show them one child and ask them to give, they'll give three to four times more money for a single child.

Because they're helping an individual, they feel.

You give them a name, you know, here's the, you know, here.

You can even use the name the child has.

That's right.

You don't even have to make up a name.

So that's the shaking the hands with the person who's on the outside of the city walls.

Absolutely.

So it tricks the brain.

You sort of bond with it, there's a little oxytocin there, some dopamine, like, okay, I'm feeling good about this person and I think I'll be nice to them rather than be nasty to them.

So I shouldn't criticize those efforts for how crass they are in their salesmanship because they really understand the shortcomings of the human emotional state.

That's right, yeah.

Those are true.

Because they're effective.

Yeah, because they're effective.

The big NGOs and non-profits, they've tried, you know, they've tried to experiment.

NGOs, non-governmental organizations.

Yeah, and so they know what to do to get the raise the most money and that's okay.

I mean, they, again, they know how to trick the human brain into caring.

Yeah, trick drunk people at night into helping each other.

So there's the whole side of psychological sciences that helps us understand the failure of our reasoning.

And then when you're equipped in advance, you can compensate for that.

That's right, absolutely.

And say, behavioral game theory has helped us get through the Cold War.

It's like, okay, they're rational actors, we're rational actors, we don't want to die, they don't want to die.

Reagan and Gorbachev, or, you know, Nixon and so on.

Yes, mutual assured destruction, it worked.

It works if one of the, the other side doesn't want to die.

That's right, so this is the problem we face now.

That's a big assumption.

This is the problem we face now.

There's people that are willing to die because they have this supernatural belief in that they're going to heaven with the 72 virgins and oh boy, I'm gonna, I'm gonna blow myself up.

Okay, they're not gonna calculate rationally.

You really only need like 10 virgins to think it's reasonable.

Yeah, what's the diminishing return on that?

I don't think there's been any studies on that.

I remember hearing Joe Rogan, a great podcaster in MMA, I guess he's ex-MMA.

He shows up every now and then to, I think to host some of those contests, but he commented of the power of sex on the human male mind that it can be promised even in another dimension.

And you completely alter your behavior to be served in that way.

Yeah, well, what's the ancient Greek play, Lysa Serges, where the women said, if you men continue to go off to war, no more sex.

And then he said, okay, let's see if we can work out a peace program here.

That's Spike Lee's current movie.

It is?

Yes, yes.

His current movie, it's Shirek.

It's a blend of Chicago and Iraq.

So it's a movie that taps the theme of that play.

And so all the women withhold sex from the men who are otherwise engaged in gang warfare in the city.

Right.

But even our discussions on gun controls, like what kind of measures can we implement to bring down the rate of homicides, suicides and accidental deaths, over 30,000 a year in this country.

Yeah, it's the same as car accident deaths.

100 a day almost.

It's appalling.

So 14 died in San Bernardino, and yet that's how many die like every couple hours just from gun accidents, suicides and homicides.

Yeah, I tweeted that, a sequence of three tweets.

One of them, the third of which got the most attention.

I just put up the number, 3,400.

Number of Americans who have died from terrorist attacks since 2001.

3,400.

Number of Americans who have died from firearms since five weeks ago.

And that works at any five week interval.

So these can be very telling to people.

Right, so the question is why is it that it doesn't happen in other countries?

What conditions do they have that we don't have?

This is a social science question.

This is a statistical variance, multivariate analysis.

What factors can we play?

It's very complicated, it's hard.

But there are some things we can do that really can make a difference.

Obviously, if a country has no guns, there's certain European, no one has guns.

But in Germany, where my wife's from, they have fairly strict gun control and mass murders like that are almost unheard of.

Right, well I think there's also the misnomer that it somehow can't work.

There's also all this false data basically that is...

There's also kind of a magical thinking about guns.

For Americans, guns are almost like a superstitious ritual.

They almost are...

But have they always been or is that the last 20, 30 years?

I think it's really just been the last few decades.

I have to agree.

All goes back to our founding.

No, not really.

The NRA used to just be a safety, gun safety...

Yeah, and like marksmen and hunters.

And then in the 70s, they kind of went crazy.

They went political.

Yeah, they're the biggest lobbying organization in the country now.

They have more power than probably any other lobby.

It's pretty scary.

Some would say it would be immoral to not have a gun.

That's right, they do.

So their argument would be something like a mutual sure destruction.

No criminal's coming to my house if he knows I have a gun.

So ergo, if every house has a gun, no criminal will go to any house.

Well, unfortunately, certain studies show that your gun is 22 times more likely to be used in a homicide, suicide or accidental gun shooting within your family and home than it is against an intruder.

Yeah, between you and someone you know.

So you get mad at your spouse vice versa, you have a depressed sibling or daughter or parent that shoots themselves, or the gun just goes off.

One of the most disturbing things that are almost funny are the YouTube videos of people who accidentally shoot themselves.

I didn't know that that was a thing.

Oh, it's a thing.

There are hundreds of these videos.

Oh my God.

I mean, there's like one kid, he's doing the Clint Eastwood thing with the gun sideways, and you know, like, I'm a badass.

Bam!

And he's like, oh, my mother's going to be so mad at me.

It's like so much for Dirty Harry.

So the idea of arming everybody is a bad idea because of accidents, because also because of human nature.

Some people have a short fuse.

And all of us, under certain circumstances, could become violent.

The potential is there.

So what else you got from our fan base?

So here's Josh I on Twitter asks, if we found life on other worlds, how would that affect the way we look at life on our world?

Yeah, so let me try to shape that.

So if we find aliens and they have a different social contract with one another, are we in a position to say, no, that is morally low, we have a higher moral fiber, here's what you should do?

Because it's kind of what Star Trek did every now and then.

You know, the prime directive is don't interfere with the civilization, but they always did.

Yeah, that'd be a dull show.

Oh, these people are awful, we should go.

These Greek-dressed aliens are so sensual, goodbye.

I saw that one, they're all in togas.

It's like half the episodes of The 16th.

Togas in miniskirts.

Yeah, exactly.

How unusual that they've adopted the fashion of the 60s in 5,000 years before that.

So is there...

Well, two things, I think.

Is this moral arc something that not only goes beyond our species?

I think so.

That's audacious, you know.

I know, but you gotta think big.

How many aliens have you talked to?

Six.

Self-identified.

Let's see, my wife's from Germany, is that an alien?

You have to be an extra-terrestrial alien.

Oh, I see, extra-terrestrial, okay, yeah.

Well, so I do speculate about this at the last chapter toward the end of The Moral Arc, that if we encountered aliens, would they be good or evil?

As you know, Stephen Hawking came out with that statement, you know, I think the aliens will be evil, they'll conquer us, they'll be colonialists and so on.

I argue just the opposite.

You can't become a viable space-faring civilization, say, a Type 2 civilization, and be like the Romans or the Nazis or, you know, some conquering, imperialistic, you know, 18th century, you know, constantly a war-type country.

So your claim is battlefield Earth is unrealistic?

Yes, that's right, yeah.

I think, really, you'd have to be a peaceful, more cooperative civilization.

You'd be more like an abstract world.

No, no, part of that argument is, if you are that expansionist, and everyone feels that way about being expansionist, and you fight wars to accomplish it, as you start colonizing planets, your expansionist attitudes then conflict with one another, and you basically self-destruct.

So there's gotta be some sense of peace and cooperation deep within how you function as a species to not implode under your own shortcomings.

That's the thing that got you there in the first place.

So Stephen Hawking said that because advanced civilizations, when they go to a new place, generally do attack them.

Is there an example that isn't the case on Earth?

He's basing that on his actual knowledge of how humans treat one another, not on any real knowledge he could have treated, not on any real knowledge he acquired from aliens, if this is a point.

And I lean towards you, Michael, on this.

Yeah, I mean, when Putin took over that portion of Ukraine, that was very unusual, and it's really the first time any borders have been redrawn with any significance in decades.

It's really unusual now for countries to expand their territory and bust in.

It's more likely that there's just regular war.

And besides, the aliens are going to traverse the vast instances of interstellar space and come here and take our coal.

I mean, surely their technologies have gone beyond fossil fuels by the time they get here.

But maybe they want all our pretty birds.

I heard a radio show back when I was in college, a radio play while I was driving, and aliens were coming, they thrive on hydrogen, and they came to Earth and were sucking up our water supply to take the hydrogen out of our water.

And I said, they must never have taken astrophysics 101, because 90% of the universe is made of hydrogen.

You don't have to come to Earth for water supply.

Just open the window.

And separate the molecule and take out the hydrogen.

When you can just take, where would it be in astrophysics?

Every star is nearly 100% hydrogen.

Every gas cloud, everything.

Jupiter is 90% hydrogen.

Oh, they'd go to Jupiter then.

Yeah, just scoop up some gas, and it'll take out a damn water supply.

So, when we come back, more Cosmic Queries with our special guest Michael Shermer.

We're back on StarTalk, Cosmic Queries.

We're talking about morality in the universe and whether science can inform that.

And my friend right here, Michael Shermer, has written a book on this called The Moral Arc, and the subtitle is?

How Science and Reason Lead Humanity Toward Truth, Justice and Freedom.

Man, you're running for office?

Yeah, I know, right?

Right, and so this is Cosmic Queries.

We solicited questions, I haven't seen them, you haven't seen them.

And so let's see how many we can squeeze into this last segment.

Yeah, let's go for it.

Eugene.

Let's do it.

Martin Badg asks on Twitter, how has our moral standing affected the pace and direction of scientific discoveries?

Oh, in the opposite direction.

Well, I do think a more open society, where there's more liberties and freedom, freedom of speech especially, and especially freedom for women to be involved and minorities and so on.

All that just makes science more appealing and more people involved in all the different scientific enterprises.

Then I think it becomes sort of a feedback loop.

More science and reason is good for morality, more just and open society is more conducive to science.

But how about some of the experiments that, you might say, why are you doing that?

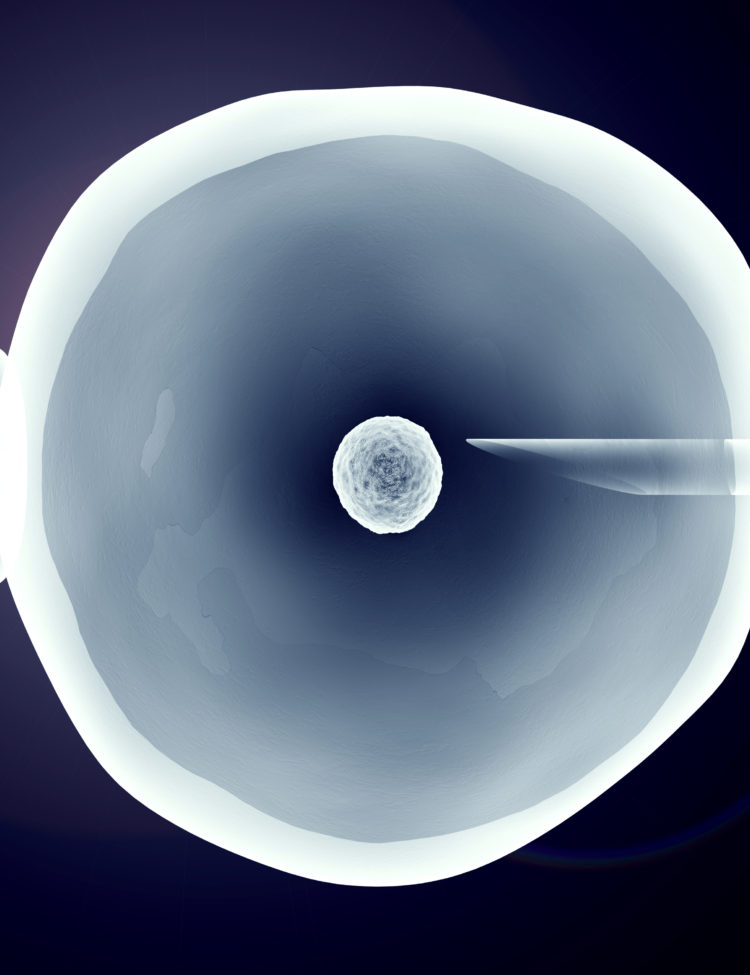

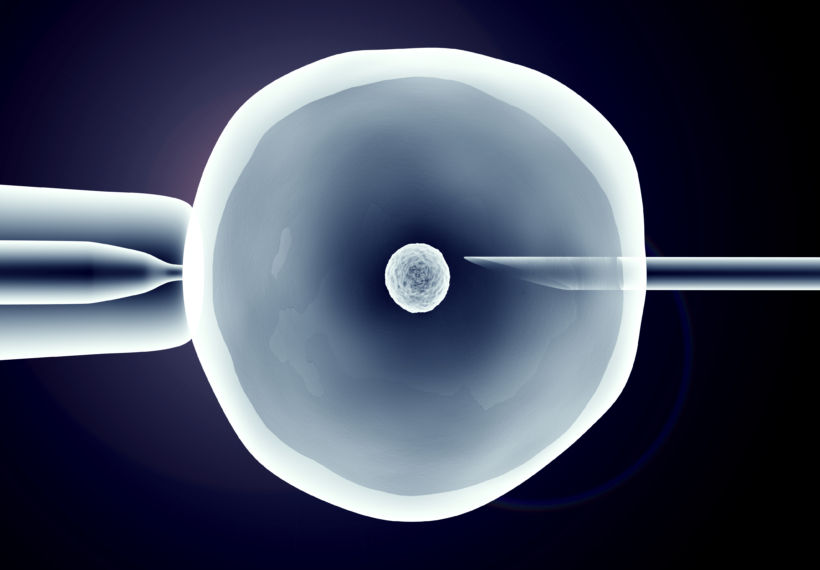

For example, if you can get the DNA from a mammoth that just got thought out from a receding glacier line and then clone it and then create a mammoth in modern times.

And I always joke that how unfortunate for the mammoth because he was just fine for the ice age and now bring him out just in time for global warming.

How cruel can you be?

Well, Canada.

Yeah, you leave them in Canada?

Yeah, there's plenty of room up there.

You plunk them down at the right latitude.

Good answer.

Maybe you put them all at the top of Everest.

I bet it's quite cold.

Siberia, there's plenty of space up there.

Good answer, I had not thought of that.

Okay, this is my first one.

Because they couldn't get there before because they would ultimately be broken off.

Now we can drop them out of airplanes.

The Canadian population is decreasing as is the Russian population, so more mammoths.

Okay, so that's good.

Another one is I was speaking with Richard Dawkins and he said something that while I agreed with it, I didn't want to agree with it.

He said if we have the power of cloning from any genetic sequence, then he would be interested in creating the common ancestor between us and chimpanzees.

I think that would be.

If you did that, it means a chimp could mate with that as well as humans.

That would be so much fun.

No, that's just.

I can only imagine how popular on the internet that would become.

No, no, I'm just saying, when he said that, it was like, why would you?

Right, it would be under specific conditions.

Yeah, so is that morality or is that just ethics?

Okay, there would be a moral question.

Or is it ethics?

Is it the same thing?

That is, do they have rights?

So I think in order to allow that ethically, we would have to grant the offspring.

Rights, and then it would have to choose who it mated with.

Right, right.

You know, there was a, there was a novel, a French novel in 1950s called You Shall Know Them by an author named Verkors, V-E-R-C-O-R-S.

It, and the story opens with this scientist who kills his son or something like, yeah, kills his son.

And then, you know, he calls the police, I've murdered my son, the police show up, and he's basically mated with a female chimp and had an offspring and killed it.

And now he's on trial.

For what?

For murdering what?

Is it a human or is it a, okay.

So that got into the, you know, what are the characteristics of a human?

This is back in the day, you know, are chimps humans and do they have tools, language, reason?

You know, that kind of thing.

But, you know, as Jeremy Bentham pointed out, as I talk about in The Moral Arc, that it isn't can they reason or can they talk, can they feel and suffer.

So always our moral consideration for other animals, including possible hybrids or a clone, would be, you know, are they gonna suffer by us bringing them into existence?

If they have a good life, then why not?

Okay, so then we can diversify the very species that we ever considered to be human.

I mean, if we explore space.

It'd be like X-Men, if you have other kinds of.

That would be really fun.

There's, and nothing ever goes wrong in the X-Men universe.

So I would like more of that.

Wait, so would this creature be able to learn and speak?

I retract, I retract it.

Would it be able to learn and speak and sort of, it'd be.

Well, that's what, I mean, what Richard is after there is, well, what can they do?

Do they have language or not?

Can they throw parties?

Okay, so the morality is not whether you did that experiment.

The morality is the product of that experiment needs to be reckoned as someone who is part of the citizenry of the system.

Right, let's give them a seat in the House of Representatives.

I think that would be a reasonable and fair thing to do.

They may be a little smarter than the current guy.

But say they were the mammoths.

I mean, we shouldn't bring them back if we don't have any place to put them.

They can't live a normal life.

Well, we can hunt them.

What?

See, this is the argument that gun people make, is that we're actually saving the ecosystem by allowing people to kill the animals.

You know, it's a reasonable argument, but in the long run, we should give them their space to just live and not be shot.

Oh.

So Eugene, what else do you have?

Kealia Silvis asks, with eugenics atrocities in the 1900s, can humanity ethically use human gene editing tech?

Yeah.

Well, okay.

So again, we have the products of science.

But before you go there, let me ask.

The Statue of Liberty and the writing, that poem from Ezra, who's the author of that?

You know, Give Us Your Weak and Your Poor.

All right.

That was the moral opposite of the eugenics movement that was trying to parse people by their desirability.

Over that same time, so you're an immigrant coming past the Statue of Liberty, you go to Ellis Island, and you have people trying to invoke eugenics on how to sort you.

So what's that about?

Conflicting political ideals, I think.

On the one hand, the idea of eugenics was really kind of a liberal movement at the beginning.

It became more of a right-wing movement later.

But at the beginning, it was, let's see how we can engineer society from the top down in all things, with laws and so on, but also with genetics.

Then after-

What was it exactly?

Well, just-

The eugenics movement?

Yeah, exactly.

Yeah, yeah, it was an attempt.

It's traceable.

I know what it is in Star Trek, but I don't know.

Even before the century, the turn of the century, there was a lot of thinking about, well, now that we understand that there's a thing called your genes, and some genes are desirable, others are not, let's breed a race of desirable genes, a race of humans with desirable genes.

And the early thinkers were thinking maybe you could do that for the entire planet.

I don't see anything that could go wrong with that plan.

But then it becomes localized, and you have Nazi, Nazi philosophies and things.

Well, you know, the state of Virginia and the state of California both sterilized more people in 1930s than the Nazis did.

So at the Nuremberg trials, one of the defense of the Nazis was that, hey, we got the idea from the Americans.

And they had a point.

But this was all part of this.

Why were people being sterilized?

Well, if you're mentally, they judge that you're, they don't want any more of your genes moving forward.

Right.

Oh, wow.

Yeah, yeah, you're mentally deficient or deformed in some kind of way.

Right.

So they started with physical handicaps and then mental handicaps and then things like work shy.

He's work shy.

In other words, he's lazy or doesn't want to work.

They started moving to more social things.

Really?

And that was legal in America?

Well, that was in Germany.

I don't know about it.

I don't think that part here.

Germany did a lot of terrible stuff.

That's well documented.

But not anymore.

And just to be clear, in these cases, they wouldn't kill you, they would just sterilize you.

They'd stop your gene pool.

But in Virginia, they didn't do this.

Well, they sterilized mentally retarded people.

Right, yeah, yeah.

And it was a famous Supreme Court case of three generations of imbeciles are enough, was the final line.

I remember that line, yeah, I read that.

Yeah, it's very disturbing.

Well, okay, so that's obviously a negative use of science, but again, science is morally neutral in some respects.

How it gets used is a political decision and a social decision.

Well, so back to science, my argument is that, but socially, politically, we're becoming more reasonable and rational and realizing that doesn't work.

And besides that, the moral agent is the person being affected.

We should ask them first.

That's the idea of individual rights and autonomy.

Before you tell somebody what to do with their genes, well, let's ask them first.

And then if you don't like their answer, then you can do what you want.

Well, sometimes that happens in some countries.

And I forgot what network it's on.

Is it A&E, which is one of these networks where they follow a group of dwarfs?

What's the one where your long bones are shortened?

Is it dwarf or midget?

I think it's dwarf.

Yeah, but they're called little people, I think is the general term.

And so there is a couple who are both dwarfs, then they have children who are all dwarfs.

And so it's their family, and their house is a little different because it serves them and not us.

And so here's a whole TV show, a reality show based on their lives.

One of the encouraging things to me is the Flynn effect.

But the Flynn effect, IQ scores are going up three points every 10 years for about the last century.

And not on the mathematical vocabulary, things you can study for, but on the abstract reasoning portions of the IQ test.

No one quite knows why this is, but the best ideas by James Flynn, the eponymous James Flynn, the Flynn effect, is that in general as a culture, we're getting better at abstract reasoning.

Just by the diffusion of scientific knowledge and the jobs people hold are more abstract in reasoning capacity.

Only 3% of the world's population is in farming now.

It used to be about 97%.

Oh yeah, more people would create more food on less land than ever before.

Yeah, so we don't need as many farmers.

So more people are working in information technology.

And then that is affecting people.

You're just, your capacity to reason abstractly.

It's very hopeful.

Also, reading, it's looking at some preliminary studies I cite in the book is that reading novels, good novels, really makes you better at mind reading.

That is the capacity to think about what other people are feeling and thinking.

And the reason for that is because in a novel, you become the character and you're looking at the world through their eyes and that retrains your brain into.

Movies don't have the same effect?

And movies do too.

Oh, good.

Yeah, no, movies.

That might be a shortcut.

Actually, comedy has an important role in The Moral Arc in the sense that comedians can bring about social criticism of leaders and particularly political leaders that in the early stages, if you get people to laugh, they kind of go along with you before they realize, oh, wait a minute, he used to make it in front of the commander-in-chief.

You know, an op-ed writer may get nailed for this in certain countries, beheaded in centuries past, but comedians can get away with a lot and that helps bring things about.

Change from the bottom up, just everybody's sort of making fun of him now.

Yeah.

So Mike, we gotta go to the lightning round.

And so that was this bell you heard a second ago.

So lightning round, it's like, we're testing your sound bititude, okay?

All right, ready?

All right, Eugene, go.

Go.

Gene, if it's a lightning round, I can't have you take 20 seconds getting into the question.

Ready, go.

Question for Neil, how can a scientist defend agnosticism?

You don't have to defend the absence of evidence for why you think what you do.

Honestly, it doesn't need a defense.

If you want to defend something, you want to defend a belief for what you have that would not then have evidence.

I mean, would you agree with that?

Yeah, absolutely.

It's always okay to say, I don't know.

It doesn't mean anything.

It doesn't mean your committee.

It's just okay, because we don't know everything.

Right.

Good, next, okay.

James Miller asks, as purveyors of truth, should more scientists publicly speak out on questions of morality and ethics?

Ooh, good question.

Absolutely, yep, definitely.

But that implies they've studied it and thought about it and can say something coherent.

Not everyone has that background.

That's right.

Einstein spoke about war.

He didn't really know what he was talking about, but you know, it's okay.

It brings us all to the table of like, hey, let's talk about this rationally.

Okay, so you want that to happen more?

More.

Okay, more.

Okay, go.

Does modern science back up any old moral platitudes that modern society ignores?

Ooh, good one.

Oh, absolutely.

The golden rule.

I mean, that's reciprocal altruism.

I'll scratch your back if you'll scratch mine, and if you stand.

Do unto others, as others do unto you.

Yeah, absolutely, that's the oldest rule, and science has continued, evolutionary biology has continued to find that to be true.

Does that include even game theory?

That is, absolutely, yeah.

Okay, nice one, go.

Jason asks, will we ever get to a point when we profile our flag individuals with criminal-like brain waves?

Well, we.

Sterilize them with lasers from the sky.

Modern phrenology, go.

No, not criminally, but scientifically, we might wanna know, are there certain conditions that the brain is under where you lose control?

For example, lack of control, lack of prefrontal cortex activity means your impulse control is lost, and a lot of violent criminals have low-functioning cerebral cortex.

And it's nice to know if someone is susceptible to that.

That's right.

You got it.

Maybe make them wear a red hat that says, I'm a menace.

Michael, we gotta end it there.

Thanks for being on StarTalk.

Not your first time, not your first rodeo, but we wanna get you back every time you have a book.

Sounds good.

All right, Michael Shermer, thanks for visiting.

And Eugene Mirman, always good to have you.

I am Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, and we're here on StarTalk in New York City.

We're signing off and I did you in that process.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron