About This Episode

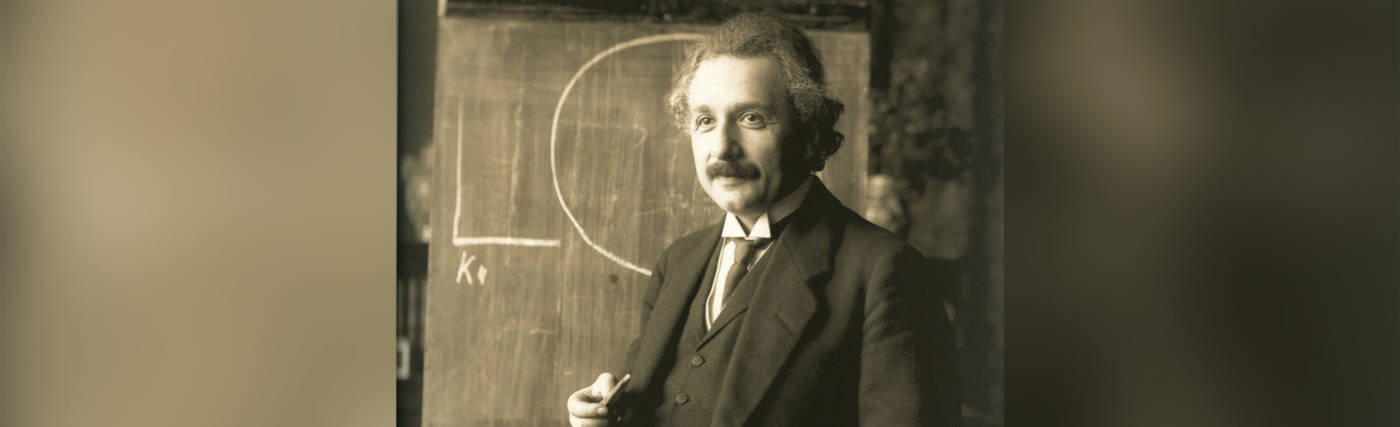

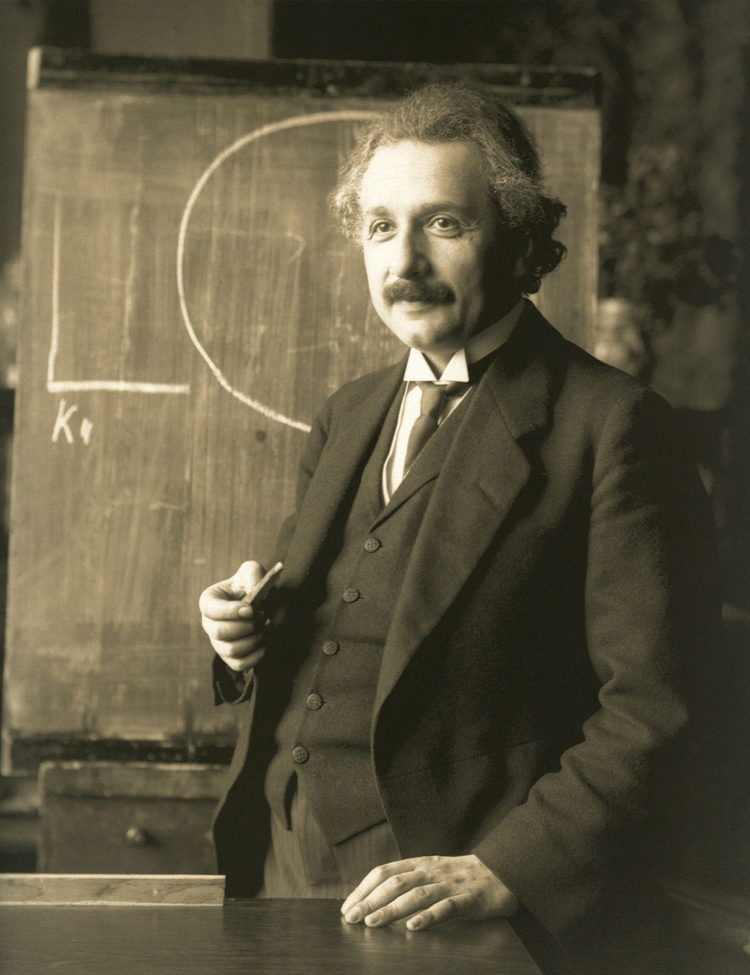

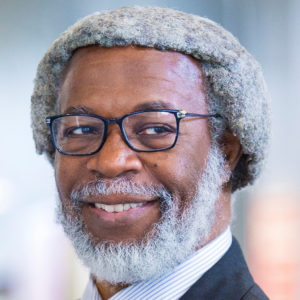

Albert Einstein is, well, Albert Einstein. But, was he right? It seems like a silly question, but, in fact, there’s some history behind it. On this episode of StarTalk Radio, Neil deGrasse Tyson and comic co-host Chuck Nice are investigating what it took to prove Einstein right, with Dr. Jim Gates, theoretical physicist and Professor and Center Director of the Brown University Theoretical Physics Center. Jim is also the co-author of Proving Einstein Right: The Daring Expeditions that Changed How We Look at the Universe.

We start with some history. Jim tells us about Einstein’s discoveries about space and time in 1905. You’ll learn about the “happiest thought” of Einstein’s life. We discuss how he came to his theory of general relativity and theory of special relativity. You’ll also learn why, even though he first started working on the ideas in 1905, it took him over a decade to get them right.

Find out what it takes to provide evidence for mathematical theories in the real world. We discuss Einstein’s exposure to the real world and how that informed his thought process. Jim explains why being a scientist involves swimming in a sea of information. We ponder if Einstein ever thought his theories were incorrect, and Jim tells us why math is magical.

Then, we answer fan-submitted Cosmic Queries! Is general relativity incompatible with quantum mechanics? If so, why? Is there a bigger idea that encompasses both ideas? We dive into String theory and how that might play into the equation. We investigate “gravitons” and how their existence would re-shape science.

Are the strings in String theory made of something? We explore the cosmic microwave background and debate if a cosmic gravitational background could also exist. Lastly, you’ll hear why some stars in the night sky might be duplicated due to the bending of light. All that, plus, we answer the most important question of all – who has a better mustache? Neil deGrasse Tyson or Albert Einstein?

Thanks to our Patrons Beverly Bellows, Christopher Mank, Darrell R. Scott, Eric Burgess, Pike Persons, AK Llyr, Nicholas Belsten, and Samuel D Fairchild for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can watch or listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

About the prints that flank Neil in this video:

“Black Swan” & “White Swan” limited edition serigraph prints by Coast Salish artist Jane Kwatleematt Marston. For more information about this artist and her work, visit Inuit Gallery of Vancouver.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTWelcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk.

I’m your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, and today’s topic is proving Einstein right.

Chuck, I needed you for this one, because you’re the man.

I don’t know how you need me, because I never knew Einstein was wrong.

So I’m trying to figure out where’s the controversy?

Where’s the controversy?

Well, to talk about that controversy, I’m bringing a friend and longtime colleague, Jim Gates.

Jim, welcome to StarTalk.

Well, Neil, it’s good to be back in the presence of a star.

James, please, it’s okay.

Thank you.

Thank you.

I appreciate you.

I would leave that one at that.

So, Jim, you’ve been at this for a long time.

Well, you’ve been an Einstein fan for sure, but a theoretical physicist and you’re director for the Center for Theoretical Physics at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

And that’s a title.

How long have you been doing that?

So, when I was 66, Neil, I was recruited from the University of Maryland to Brown.

I went around telling my friends, asking friends, why do you think they want an old car?

No, it’s not the age, it’s the mileage, okay?

We know this.

Well, one of my friends said, Jim, you’re not an old car.

You’re an antique car.

Oh, oh, there you go.

The Preservable Antique.

They hold their value.

I’m going to go one better than your friend, James.

You are vintage, my friend.

You are vintage.

Vintage.

Vintage gives you even more money than antique, as they say.

Okay, well, I switched after 33 years at my previous university.

Came here and…

Where was the previous university?

University of Maryland, College Park.

Wow.

And are you still on speaking terms?

Because I would be kind of angry after 33 years that you just up and leave me.

Just leave our marriage after 33 years.

Well, I don’t know if marriage is the right analogy.

But independent of debating that particular…

We did part of the terms.

In fact, I’m an emeritus professor there.

And as an emeritus professor, I have taught two consecutive years courses on public policy.

Nice.

Evening courses.

So, I’m on good terms.

So, if I remember correctly, you were on Obama’s advisory council for science and technology, right?

That’s exactly right, Neil.

I served seven years on the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, PCAST, the acronym.

PCAST, that’s right.

That’s right.

But you were in the current administration, they didn’t invite you back in there, huh?

I thought we were going to try to keep…

All right.

We’ll leave it at that.

Thank you.

That’s all right.

I was invited to be on this current administration’s advisory council on writing jokes about technology.

So if you’re director of the center, that’s not necessarily an academic title, that’s a job title.

So you’re also professor of physics.

Indeed.

I’m an endowed professor here at Brown University.

The endowment is before, I’m the so-called Ford professor of physics.

I’m also an affiliate mathematics professor.

And on top of that, I’m a faculty fellow at the Watson Institute for Public Affairs and International Affairs.

Excellent.

So we should bring you back for seven other excuses, seven other reasons.

Forget the theoretical physics.

We got some policy we got to figure out here.

So what we’re going to do is we’re going to structure this program.

We’re going to spend the first segment just talking about why was Einstein proved right or why did he need to be proved right?

And then we’ll go to Q&A.

We go to our Cosmic Queries.

And Chuck, you got Cosmic Queries for section two and three?

I have the questions right here and I have to say these are some…

Man, people are excited that you’re here, Professor.

They are excited that you’re here.

We got some great questions.

There’s no one that triggers more questions than Einstein and relativity, and we got the man for it.

Well, I would say Einstein, relativity and Tyson.

And what?

And Tyson.

Okay, right on.

So, Jim, you published a book in 2019 called Proving Einstein Right, and let me get the full title, The Daring Expeditions That Changed How We Look at the Universe.

Sure.

And do you have a co-author?

Who was that?

I do have a wonderful co-author.

Her name is Kathy Pelletier.

She lives in Allagash, Maine, which is just right across walking to Canada.

And this book is not what people expected.

Usually, you know, Neil, your first book, as I recall, was partly autobiographical, right?

Well, that was one of my first, my fourth book, yeah.

Okay, fourth.

So what I wanted to do with this was to do something I had never seen done before with physicists.

Usually, people talk about the wonder and the majesty of looking at nature and the struggle and what have you.

But what I wanted to do, and I had wanted to do this for a decade, is to write a book about the interior lives of the people who do the science.

And so this book is actually dedicated to eight astronomers and Albert Einstein.

And yes, we tell the scientific story, but what we really want to do is get inside of their heads and tell the story of what they were feeling as they went through this almost decade-long struggle.

So the book surprises people.

Okay, so the book was published in 2019, and if I remember my history, that’s basically the centennial of this big experiment that showed that Einstein was right.

That’s right.

But let me back up a little bit.

So most people, I mean, physicists know Einstein for many things, of course, but for special relativity and general relativity.

I think often when people think of Einstein, they think of the effects of sort of ordinary relativity, like time dilation and this sort of thing.

So that would all happen in 1905.

That’s correct.

So why, if that’s all happened and it worked, and it was, you know, it was smoke ineffective at explaining our understanding of the universe, why didn’t everybody say, yeah, Einstein is the man?

Why did they have to wait another 10 years for them to prove some other thing that he did?

So let me talk about Einstein in 1905, and thank you for giving me this opening.

As you know, Neil, in 2005, there was the so-called Einstein Year of Physics, and there were celebrations all over the world.

I gave 37 talks on six continents on Einstein in that year.

I thought there were only five continents.

I get my numbers confused.

Thank you.

You left out Antarctica.

Because that’s the one I’ve never been to.

But the penguins will welcome you with open arms.

And happy feet, yes.

But the point was, yes, you’re right, Neil.

In 1905, he came up with some amazing things about space and time and how they bend and warp and what have you.

But do you know that in 1907, he was still in the Patent Office?

People think that as soon as he came up with his wonderful theories, the world beat a path to his door saying, Hosea, Hosea, you know, whatever.

But no, no, no, that’s not what happened.

It’s Hosanna.

Wait, Hosea.

Yeah, Hosea is the prophet, but Hosanna is the praise.

But we knew what you meant.

Well, this is what happens when you go off script, guys.

But anyhow.

I’m sorry.

No, no, but you’re right.

But the point was that he did this great piece of work, but it took two years for the physics community to recognize what he had done.

Wow.

Well, he was in that patent office still trying to figure out how to get a job as a physics professor.

He looked out the window one day and he saw some workmen on the roof.

And he had this sort of story coming to him that if one of the guys fell, he wouldn’t feel his weight.

And so that started Einstein thinking about gravity.

He’s thinking about the death of someone working on a roof next door.

I did not know this.

Well, not the actual death, but the process that would lead to it.

Just his fall to eminent death.

That’s just the eminent fall.

I did know Einstein had this morbid side of him.

Yes.

Let me just say, I totally get it, because I think about the death of the guy that blows that leaf blower outside my bedroom window every Saturday morning.

And so Einstein started thinking about gravity.

And so this is like him.

In fact, he calls this the happiest thought of his life.

Wait, wait, so wait, so Jim, this is like Newton’s apple moment.

He sees the apple falling, and then he sees the moon, and then there’s a eureka moment in there.

And that’s what happened with Einstein in 1907.

So the thing that’s curious about Einstein is, although people think about him as this mathematical genius, every time he did something, he actually had to learn more mathematics.

So he didn’t actually have the mathematics to realize what his intuition was.

And he didn’t get it right until 1915 or 16.

You know, Jim, that happens to me all the time.

I have thoughts I have to invent new math to, you know, that’s just a thing.

You know, some of us actually do that, Neil.

That’s another whole story, and I’ll tell you about that one later.

But anyhow, so he had this idea that took him almost a decade to get it down to the mathematics.

And when he finished it, it was the theory of general relativity.

It’s the piece of thing that tells us that there was a big bang.

It’s the piece of mathematics that lets us know we live in a universe that is 13.8 billion years old.

And so that came from that 1917 epiphany.

Wow.

I mean 1907.

1907.

Right.

Right, right, right.

Now, remember, it’s all math.

It’s all math.

So if it’s all math, how do you know he got it right?

Right, just because the math works doesn’t mean it has to correspond to any objective reality.

Exactly.

And so when he finally gets his discussion together, in fact, even before he gets the right answer, he starts talking about it.

He starts giving talks about it.

And so very early on, astronomers realize, well, he realizes first, that astronomers would be critical to try to prove that his math is actually, as you said, Neil, something that happens in the real world.

And he begins it by talking to this German astronomer named Irving Findley-Foindlich.

I had never heard it again.

No one’s ever heard it.

If I’d ever met someone named Irving Findley-Foindlich, I’d remember that.

I’m pretty sure.

Well, I have sent, for your program, I’ve sent some photographs of all the people that we’re talking about.

That’s the first guy that Einstein starts talking to seriously as, you know, I have a way to prove my man.

And he first starts saying, if you look at starlights, could you show that starlight bends when it passes near Jupiter?

And the astronomer says, you know, no, that doesn’t quite work.

Then he starts asking questions about, but suppose we were looking at the night sky in the morning or early morning or late afternoon, could we see bending starlight around perhaps Venus or something?

The guy says, you know, the astronomers go back, no, no, that won’t work.

And so finally, by this set of discussions with Freundlich, he hits upon the idea that if you could watch starlight during an eclipse, you might be able to see the light being bent by the sun.

Because you can’t otherwise see a star in broad daylight.

Exactly.

So, you know, it’s a very special circumstance.

And so that starts the race.

So this bending of starlight would have been the first experimental verification of his general theory of relativity.

Yes.

And so now, so what year did that happen?

Was that conversation?

These conversations were around 1912 or so that he starts telling other people about his ideas.

Okay.

And that’s how you get the creativity of other people to help you figure out how to make it work.

Bingo.

And that’s what our book is about.

It’s about the other people.

It’s not really about Einstein.

So what’s all this we hear about his wife possibly being a big engine to his creativity?

A lot of people have, well, there’s this one book, Einstein’s wife, I think is the title.

There are a lot of people who have posited that as having been important.

But from my reading of the history, she was certainly his partner as he was working through and Byrne as a poor patent examiner, trying to do physics.

She was certainly a partner.

So Byrne, the city in Germany.

The city in Switzerland.

Oh, Switzerland, excuse me.

Right.

So she certainly was his partner there.

But in the actual settling of the special theory of relativity, and I’ve read over a dozen books trying to get this straight in my own head, the preponderance of evidence is that he worked it out with a friend of his on a tram ride thinking about the clock tower in the city of Byrne.

So, I mean, it’s a fantastic story.

What you’re saying here, Jim, is had Einstein been a loner and not traveled anywhere, he wouldn’t have come up with any of his ideas.

How much life exposure is the right amount to fully realize your creativity that can be expressed?

I tell people all the time that being a scientist means that you swim in a sea of information, and that information comes from your colleagues.

So, you cannot be…

I mean, I know the archetype, stereotyped view is that as a scientist, you go off in the corner and you sort of think big thoughts.

But that’s not what actually happens.

I’ve lived this life for over 30 years, and you are constantly in conversation with your colleagues, and you use them to hone and to refine your thoughts and distill your thoughts and curate your thoughts.

So, Jim, the active word there is that you are swimming in these influences, not drowning in the influences.

Yeah.

So, that’s why I, with Kathy Pelletier, we wanted to talk about these people that basically were using what Einstein and Sparrow did, but to swim towards this discovery of whether his math was an accurate description of nature.

Wow.

Do you think Einstein had any doubts about whether it was all true?

From my reading, no.

He sort of says things like if the theory of general relativity had failed to receive experimental and observation support, that he would have felt sorry for the good Lord.

Because that was a really brilliant idea.

Right.

Which is kind of a way of saying I’m smarter than God.

It definitely says that.

No, it doesn’t.

No, Jim, you’re lying.

No, I’m not lying.

If you read a lot about Einstein, you find out he’s a very, very complicated character.

Chuck, since you brought up the issue of God.

And you did bring it up.

I did, yeah.

I mean, to me, when somebody says that statement, it kind of sounds like, you know, I’m smarter than God.

No, but you see, although you can interpret that statement that way, that’s not really what Einstein felt.

Because, in fact, he talks also about the illimitable spirit.

That is a spirit without limits.

So it’s clear that if you can use a phrase like that, you’re not putting yourself above such an entity.

All right, that’s a very good point.

He didn’t use that phrase in that sentence, though, but okay.

Not in that sentence.

In that moment, he felt badass, is all I’m saying.

It’s not, but yeah.

Because it is, you know, Jim, before we go into the second segment and solicit our Cosmic Queries, just give me a minute or two.

I know it should be hours or two, but give me a minute or two on the idea that math is just something we invented as humans.

And it works.

What’s up with that?

There’s no reason that it should work at all.

You know, Neil, this is one of the most…

This is the only piece of magic that I’ve ever experienced and seen in reality.

I love that.

I love that.

It’s magic.

It’s a piece of magic, but it happens to be a part of our reality.

I don’t know of any other form of magic for which I can say this.

And this is human created magic.

We create something and it magically describes reality and enables you to predict and understand and extend.

It acts like a third eye for those of us who are scientists.

It lets us see things that are not seeable otherwise.

I made a presentation at the New York Academy of Sciences about three years ago, two years ago, and it’s precisely on this point of the magic ability of mathematics.

It’s an hour long interview, so I’m not going to bore you with it.

Is it on YouTube or something?

Yeah, it’s available on YouTube.

Forgive me, I’ll go find it.

The New York Academy of Sciences is a long venerated institution.

Absolutely.

I was there with Margaret Wertheim, and we discussed this magical thing, this thing about mathematics.

At the end of the day, one of the things I said about it is that mathematics, as people like me use it, it’s the only human language that we know accurately allows us to describe nature.

However, any other conscious being that could produce mathematics will have access to this knowledge.

So hence the idea that if we meet up with aliens, we might start with this symbolic representation of what is and is not.

Sure.

And math could be the only way we can prevent ourselves from getting our brains sucked out by the evil ways.

Many of us think that that’s right.

So when we come back more of this edition of StarTalk, we were talking about proving Einstein right.

We’re going to go straight to our Cosmic Queries version of that.

We’re back, StarTalk, proving Einstein right.

Chuck, thanks for being there, as always.

Always a pleasure, always a pleasure.

And we got Sylvester Jim Gates, a long-time friend and colleague who’s an Einstein expert, a theoretical physics expert.

He’s all the kind of expert you need for this.

Absolutely.

For this incarnation of StarTalk.

And we’re gonna devote this segment to Cosmic Queries.

Jim, your presence on our show was announced to our fan base and they got completely excited by this prospect.

Oh, my goodness.

And so, I have 5%, no, I have 3% overlap with Jim’s expertise in this subject.

So if I can find a 3% way to add, I will, but basically this is all going to Jim.

So, Chuck.

Excellent.

Do it.

Not that it needs to be said, but I have 0% overlap with Jim, which is why I’m reading the question.

So here we go.

All right.

Let’s start.

You know what, before we start, let me just quickly, can you, Professor, give us a quick breakdown between the special and the general when it comes to relativity?

I think that might be a nice framework for anybody who didn’t ask a question to be a part.

Thank you, Chuck.

So let me start with special because it’s simpler.

You know, if you were standing by a road and there was a car that was speeding towards you with its horn blaring, what would you actually hear?

It would go something like, ah, right, because you would hear that dip in the tone.

That’s called-

It sounded like you were dying.

I was going to say, Well, yeah.

I could do better than that.

Here we go, ready?

Okay, let’s work with that.

Nothing’s dying there.

We’ll work with the cat sound.

By the way, in his spare time, Neil does sound effects for Warner Brothers.

I can see.

And so, the point is that effect is because sound changes its frequency if it’s moving towards you, that’s when it’s high pitched.

Or-

But if it’s moving away from you, this pitch goes down.

Exactly.

So, the point is light actually does the same thing.

When a light source is coming towards you, it appears to be bluer than it actually is.

When it’s moving away from you, it is appearing to be redder.

And that is one of the primary effects of special relativity.

It’s about the relative motion of you and the source of the light.

In my car analogy, it’s this motion of the car either towards or with you.

So that’s what special relativity is all about, is if I’m moving and you’re not, how do I perceive things, how do you perceive things?

That’s the simplest, that’s my five-minute class on special relativity.

Cool.

We good?

And so, and then-

No, general, no general relativity.

Can you not suppose that against the general and the distribution of mass and all that stuff?

Right, so the general theory of relativity is something very, very, very different.

And what the general theory of relativity is about is what is gravity?

You see, in the special relativity, Einstein wasn’t thinking about gravity.

He was just thinking about how things would look if I’m moving.

But in the general theory of relativity, theory of relativity, the question is what actually is gravity?

It’s a very deep question that even Sir Isaac Newton didn’t get the answer to.

And the answer that Einstein teaches us through his mathematical wizardry is that gravity is the space which we move through and time which we experience durations in are combined to this thing he called space time and gravity is the bending of this thing.

So that’s my short course on general relativity.

Cool.

All right, that was great.

That was great.

Okay, let’s go to Izzy Rohr who says…

Wait, is this Patreon?

Do we do Patreon people first?

Yes, sir, thank you.

Yes, we always start with a Patreon question because Patreon people give us money, so…

And for that, we are grateful and we show our gratitude by giving you special preference.

Wait, wait, wait, so, wait, wait, but Chuck…

Yeah, we’re just like Congress.

We’re just like your congressmen.

But Chuck, this just in, apparently all your questions are Patreon questions, I have just learned.

Oh, excellent.

This just in, this just in.

Every single one of them, so guess what, all of you.

So thank you to all of you.

Izzy Rohr, Neil, Chuck, Jim, this is your friend, Violetta, the astrophysics loving kid here in Birmingham, Alabama.

My mom, oh, you know her?

Okay, cool.

Excellent.

My mom and I have many discussions, have had many discussions about this.

Scientists like to describe Einstein’s general relativity as being incompatible with quantum mechanics.

They say things like, they mathematically don’t work out or don’t work together.

So our question is, why the heck is that?

Yeah, Jim, yeah, what’s up with that?

Okay, so let me give me a second here because I got to phrase this without the mathematics.

So the idea-

That is so funny, by the way.

Okay, let me just say, that may have been the most physics thing I’ve heard in a very long time.

I’ve got to figure out a way to say this without the mathematics.

Well, you see, I don’t know if you folks-

It’s like, I’m sorry, me no speak English, me speak mathematics.

Chuck, you may not know this, but Neil can tell you this.

Often at the end of my email messages, I ask forgiveness for spelling and punctuation errors because my first language is mathematics.

English is my second language.

So I’m at a disability when people ask me to talk.

Listen, I’ve never heard a person admit a fault that makes you better than most people.

But it causes me difficulties, Chuck, on many, many occasions.

Okay.

Okay, but…

Back to quantum.

Okay, so what essentially happens is if you believe the universe is quantum mechanical, then it forces you to forget about things like electrons.

Because electrons we think about as little tiny balls.

That’s the classical picture that you’re taught.

And in fact, quantum mechanics says, no, that’s not the way it works for electrons.

You have to think of these things that are more like waves, except when they act like particles.

So that’s the first thing quantum…

It gives you this really weird thing that you have to give up an idea except sometimes.

Right?

Right.

So now when you…

So there’s a piece of mathematics around this called Schrodinger’s equation.

So I got to bring that in.

And it tells you how to…

If you’re going to bring up Schrodinger, you can’t leave out his cat.

Exactly.

Or that litter box, which hasn’t been changed in God knows how long.

Schrodinger’s litter box.

That’s what I’m about.

Schrodinger’s litter box.

We can also go back to Neil’s rendition of a car horn as it approaches you.

But anyhow, so you have a piece of mathematics around giving up the idea of particles.

And when you now give that piece of mathematics up and try to do gravity, you find out you just get into a total mess that you cannot calculate answers anymore that take into account the quantum behavior.

And that’s the mess.

So that’s the disconnect there, is that Schrodinger’s equation, once you remove anything, none of the gravity stuff works.

Because the way that Einstein and Newton and all those folks thought about gravity has the idea of particles embedded in it.

That’s the problem.

All right, so at the end of the day, who’s got to give?

Is gravity going to bend to quantum physics?

I see what you did there.

I saw what you did there, Neil.

With the gravity bends?

Yes.

Yes.

Oh, you know, Neil, this is actually a very deep question.

Or is there a third idea bigger than both of those that then encloses them under one umbrella?

There are variants of everything that you’ve just said.

Well, first of all, who’s going to bend?

There are people who will tell you that gravity is going to be one that loses the discussion.

If I had to bet, I’d lean that way too, yeah.

Yeah, and there are a lot of people who believe that somehow gravity is going to have to give way in some manner.

There are other people who have this third idea approach that you were talking about, Neil, and sort of emblematic of that is a discussion that’s underway about information and black holes.

I know Neil is probably aware of this, but there’s this whole discussion about whether information is conserved.

Like we say, energy is conserved.

Is information conserved?

And if you have a universe with black holes, doesn’t that mean that some of the information disappears and then you violate a conservation law?

So there’s a whole big discussion in theoretical physics that’s been underway for over a decade about black holes and information conservation.

So when you talk about information, are you referring to, because we just talked about this last week, give me one second please, that when Neil was talking about virtual particles and the evaporation of a black hole, and if I’m not mistaken, then this particle actually materializes on the outside of the black hole, and then that is what escapes.

And so then if that were to happen, are you saying that that somehow messes up this whole idea of the conservation of information?

But Chuck, you were really paying attention in that episode.

It does seem like it.

Neil, why do you think I do this job, man?

Yeah, okay.

So that’s what…

Okay, that’s it.

But the point is that it’s in a state of flux.

We don’t know what the final solution is going to be.

But many people like me actually think that string theory will have something to do with the resolution.

So the string people think this.

Well, it’s not just string people, I think.

I don’t consider myself a string person, for example.

I am someone who’s spent their life working on supersymmetry, and strings happen to intersect that.

Well, I consider myself a string cheese person.

String cheese, yes.

That’s about as close as I’m getting to it.

All right, cool.

All right, go on, next one.

Here we go.

This is Paul Bogle, who says, Recently, between the detection of gravitational waves and a photo of an event horizon of a black hole, some significant predictions made by Einstein’s general relativity have been verified.

What’s the next big prediction made by general relativity that scientists are testing?

Thank you.

So that’s a great question, and it’s a great question, and the answer is the following.

In 1905, Einstein wrote four papers.

Among those four papers is one that points out that energy has to be quantized.

Now we know that Einstein doesn’t like quantum theory, but in fact he’s one of the fathers of quantum theory because of this 1905 paper on the photoelectric effect.

Just to be clear, he didn’t like it because he didn’t think the universe should be probabilistic.

That’s exactly right.

He wanted determinism, as it’s called, whereas as quantum mechanics says, no, you can’t have determinism.

You have to go with probabilities.

So the answer to your question, Chuck, is now that we have seen waves of gravity, we want to see the quantization of the energy carried by those waves.

Because when we do that, we will have the Star Trek graviton in our universe.

So the same way we know light has a particle, are you saying that gravity has a particle?

Or, wait a minute, it would have to be that we find this gravity particle?

That’s correct.

That’s the next big prediction that we want to find from the kind of experiments watching graduates.

You want to be able to see the quantization of the energy that the gravity waves hold.

That tells you that gravitons, just like you hear in Star Trek, you know, all this talk about graviton waves, at that point it is no longer science fiction.

It’s a piece of science.

And Chuck, just to follow your line, so a photon is a particle of light, but you can also speak of light as waves.

Right.

Right.

So that is a proper analogy.

We have measured gravitational waves.

Now we want to measure the gravitational particle.

Oh, my God.

You have a photon, then you have the graviton.

So I don’t know any experiments out there to measure a graviton.

Is there something in the works?

No, nothing to my knowledge, Neil.

I don’t know anyone who’s…

This is going to have to be an exquisite experiment, and we’re just at the stage of just being able to see the gravity waves.

So, you know, is it 50 years?

Is it 100 years?

I don’t know.

But as our technology improves, someone is eventually going to figure out how to do that detection.

And then we can stop saying that Captain Kirk is the only guy who gets to talk about gravitons.

So if…

Just a quick question.

If we have gravitons, then gravity being the curvature of space and time has no meaning in the presence of a graviton.

Ah, you’re following along here.

For a lot of people, the detection of a graviton will likely necessitate a real rethinking of what gravity is.

I mean, some of us already are there.

I don’t actually think about gravity in terms of geometry.

It’s field theory.

That’s the tool for people like us.

All right.

So what you’re saying is Einstein’s curved space happens to be a convenience under certain situations that get you the right answer.

Yes.

And you’re good with that, but it’s not the total story.

Nope.

Okay.

There you go.

Okay.

So just let the record show, Chuck, that Jim Gates just said, Einstein had his head up his ass.

He just said that, just to make it clear.

That’s funny.

I’m not saying that.

He was like, send your letters to Neil.

The professor is like, send your letters to Neil, because I did not say that.

Actually, we got to take a break.

And when we come back, we’ll go through our third and final segment of Cosmic Queries, Proving Einstein Right on Star Talk.

Hey, we’d like to give a Patreon shout out to the following Patreon patrons, Beverly Bellows and Christopher Mank.

Guys, thank you so much.

What would we do without you as we make our way across the cosmos and create this show for everyone to enjoy?

And if you listening would like your very own Patreon shout out, please go to patreon.com/startalkradio and support us.

Thank you.

We’re back, StarTalk, Proving Einstein Right.

And Chuck is helping me, because you’re a big fan of special and general relativity, aren’t you, Chuck?

Oh, without a doubt.

Are you kidding me?

Come on, man.

Yeah, yeah, of course.

But of course.

Some people like reality TV.

I like RelatV.

Okay, that didn’t work.

No, that so did not work.

But anyhow, but you’re on social media.

What’s your best place people can find you on social media?

At Chuck Nice Comic.

Thank you, sir.

Appreciate that.

Chuck Nice Comic.

And you even have a, I stumbled on this.

You never told me this.

I stumbled on one of your, you have a Ted Talk on technology and the future.

I do, technology and the unintended consequences of human interactions.

Yeah, or the absence of human interaction via technology.

Yes, I stumbled on that.

I’m angry with you for not telling me in advance about that because I have to find that on my own.

We’ve got Jim Gates, an expert in theoretical physics.

Jim, do you have a social media platform?

I do.

It’s Dr.

Jim Gates.

You can see there’s a Twitter version and a Facebook version.

Doctor, it’s just DR, I presume.

Yeah, all right, we’ll find you there.

And you’ve got this book, Proving Einstein Right.

And co-authored with Cathy Pelletier.

Yeah, so we’re continuing our Cosmic Queries.

And just before we begin, and Chuck, before you read one in, Jim, you’ve got a background there that looks, it looks kind of spacey actually, but then not quite.

Yes.

Could you give us a minute on that?

Sure, so I’m in the odd position, Neil, where it looks like both of my twin children are going to become physicists.

So this is, you know, this is not something I set out to do, but.

Yeah, right, yeah.

Yeah, keep telling yourself that, okay.

So my daughter works with black holes.

And so she’s actually started publishing and I actually had a chance to watch her give a talk this week, so, you know, big props to my daughter.

Her name is Delilah.

But I also got to give big props to my son.

The background that you’re looking at, these green little splotches are artificial neurons that he’s been growing in the laboratory because it looks like he’s going to be a biophysicist.

As a host.

Okay, Chuck, he’s creating the next generation superhero or superhero villain.

Yeah, without a doubt.

Black holes and growing neurons.

The daughter will harness the power of the black hole and the son will imbue some being with that power to rule the world.

Have you ever heard of, have you ever worried about dark side?

The dark side, there it is, there it is.

Who knows?

Jim is breeding the dark side.

So this, is it an actual photo or it looks like artwork?

No, no, it looks like artwork.

This is actual photo of some of the first successful cell lines that he’s been growing that where you can see the evidence that they’re developing a ganglia-like real brain cells.

Sweet, man.

Wow, that’s amazing.

We’ll watch that space.

That’s so important.

Okay, cool.

All right, let’s get to the next question, Chuck.

Yeah, big brain stuff going on in that family.

All right, here we go.

Let’s go to Lisa Hansen.

And she says, hello to you all from the Bay Area.

String theories are so involved and fascinating.

I love trying to wrap my brain around them.

I’m wondering what, if any, other scientific disciplines are involved in the research for evidence and proof of these theories, what those clues might be.

Well.

Yeah, clues in this real universe, Jim, and not just an imagined one.

You know, it’s very interesting that that question came up because just last summer, I did something for the first time in my life, because I tell people, I exist at the boundary of mathematics and physics.

So I’m a fallen mathematician in some sense.

But last summer, I published a paper along with my colleague, Stefan Alexander here at Brown University, Evan McDonough, who was one of our post-docs, and my post-doc, Konstantinos Koutoulakis, as well as our graduate student, Leah Jinx.

And in this paper, we set out a premise that strings might be able to write structures, create structures that could potentially be observed in the cosmic microwave background.

We call these structures Susie-Rills.

They’re like these funny patterns.

I hope people are familiar with the CMB.

It’s this microwave radiation that you can detect by looking at the universe.

And what we showed in our paper is if you take the ideas of string theory seriously, they have a way of writing a kind of signature in the structure.

So what kind of science do you need?

You need to be an astrophysicist, someone who could actually look in microwaves at how the universe gives us a perspective.

Once again, it comes down to the astrophysicist.

Of course.

Absolutely.

Absolutely.

Look, Einstein.

Wait.

Einstein needed astronomers.

Green theory may well need astrophysicists.

So that begs the question.

In that collaboration, who was Batman and who was Robin?

Just a quick thing, if I remember, Stefan Alexander, isn’t he, he’s the jazz musician, isn’t that correct?

That’s exactly right.

Stefan is a professional level jazz musician, although he is a physicist on faculty here at Brown University.

I should have said that differently, he’s also a jazz musician.

So he wrote that book, The Jazz of Physics, or The Physics of Jazz, or something.

That’s exactly, that’s not The Jazz of Physics, it’s his work.

Cool, man.

All right, great stuff, that’s great stuff.

Let’s move on to Josh V who says, who has more impressive mustache, Albert Einstein, or Neil deGrasse Tyson?

Do you know, I gotta say, anytime I’m on, I gotta show up in a movie or in a documentary, and they put you in hair and makeup, you know, and so they do the makeup, fine.

And then they get to the hair, and they say, can we trim your eyebrows a little, and can we get some of the loose hairs out of your mustache?

And I’m saying, wait, this is my Einstein look.

You wanna be all trimmed and manscaped?

No, you need a wiry, unkempt, just wild mustache.

Yeah, so what’s with that look, Jim, that Einstein sported?

So, I’m not sure what the question is.

You know what, with that as the answer, we should just move on, because that was hilarious.

Let’s just go to Sam O’Neill, who says…

Wait, just about eight years ago, I was nominated for the Moustache Hall of Fame.

Just so you know.

I’m going to return that I was once inducted into the Luxuriant Hair Association.

That’s a thing?

It was at the time.

Okay, here we go.

This is from Sam O’Neill.

He says, hey, Dr.

Tyson, hey, Dr.

Gates, what’s up, Chuck?

My question is, what do you theorize that the strings in super string theory are made of?

Love you guys, I would give you money, and I do.

Samantha from Earth.

Oh, from Earth, excellent.

My question is PayPal.

Patreon on this side of that.

Oh, okay.

Someone’s got to explain that to me.

There you go.

That’s all you, Jim, so go for it.

So the thing about string theory, which perhaps isn’t completely understood, is that we don’t think strings are made of anything.

They are the fundamental thing if it’s a correct picture of the universe.

They are the thing everything else is made of.

That’s right.

Therefore, you can’t say what it’s made of, because it is the thing that everything is made of.

That’s all we know.

Wow.

That feels like a cop out there.

I was about to say, that’s a little circular.

That’s slightly circular.

No, no, Chuck, you’re right.

But you see, one of the weird things about mathematics is that you have to take some things on faith.

There’s actually a mathematical theorem that says this.

It’s called one of Gertrude’s theorems.

So this is one of the really weird things about math that people do not appreciate.

Well, no, Jim, be fair.

It’s not that you have to take it on faith.

It’s that you have to assert that it’s true.

If you assert that it’s true, then everything else works.

It’s assertion.

It’s not, gee, I hope it’s true.

No, you just declare that it’s true and then take everything from there.

But you can’t prove the thing that you assert that’s true.

That’s not faith.

And therefore, it’s an element of faith, Neil.

I use faith in a different…

I know.

I know you do.

We have to have another discussion about it.

We’ll get you back seven other ways on the show.

I’d love to talk to you about it.

We’ve got other business to resolve here.

If only George Michael were here to settle this debate.

OK.

Sorry, pop culture reference shouldn’t have bothered them.

From 1987.

I know.

I know.

Damn, Chuck.

I can’t help it.

How old are you?

He looks young.

Doesn’t he, Neil?

He does.

He uses that oil of old age.

It’s just an oil of old age?

OK, I’ve never heard that before.

I like that.

I heard that from an old friend of mine.

Oil of old age.

I like it.

All right, here we go.

This is Woody.

He says, after seeing Neil’s enthusiastic response, what are Jim’s thoughts on a cosmic gravitational background?

You just talked about the cosmic microwave background and string being able to be visible in that.

What about a cosmic gravitational background?

Do you have any thoughts?

This would be the paw print of the birth of the universe expressed in gravitational wave.

It would be, and I don’t see, I’ve never actually heard a scientific discussion of this, but that idea, it really seems well grounded.

No, that if one could, I mean, look, the cosmic microwave background is an electromagnetic background.

It’s microwaves, right?

Just like the microwaves you cook.

It’s light, it’s light.

Right, it’s a form of light.

But a gravitational background, a gravitational signature from the Big Bang, I don’t see any reason why that’s not possible.

I’ve not heard of any scientific discussions of the concept.

Okay, so part of why the cosmic microwave background is so useful to us, not only that it exists, but we have a map, a very detailed map of its structure.

And right now when we’re detecting gravitational waves, oh, something happened, we think, over in that direction of the sky.

You know, we have nowhere near the mapping precision to possibly do anything interesting yet.

And I don’t know when it would come.

Oh, I would give us about 20 to 30 years, because in order to do what you’re saying, Neil, first of all, we have to get a sufficient number of gravity wave detectors.

Right now there are about four in the world that are one.

There’s one, for example, in Europe, there’s one in Australia, and there are two in the US.

So that’s the minimum number you need to do the mapping.

And they’re not all sort of fully functional.

So we’ve got some time.

Right, and then you want to get gravitational waves of different wavelengths.

So it’s not just this one that came through.

Get the whole spectrum, if I can borrow that word from light.

And then you have this two dimensions of information to interpret.

So yeah, we’re not there yet.

But if we were there, it would tell us a whole lot about the very first moments of the year.

Exactly.

And that’s where science is pushing toward.

Cool.

That is super, super cool.

Roman Precop says this.

Is it possible that some of the stars observed in the night sky are duplicated or multiply duplicated due to light bending and gravitational fields of a massive object like some super black hole?

I should let Neil answer that.

Thank you.

Go ahead, Neil.

Yeah, I could take that one.

So the answer is yes.

Next question.

So what happens is that the way this unfolds, by the way, Einstein first predicted that you could make a ring, a little Einstein ring where the light would bend symmetrically in all directions around a single object and create a ring of light from that single object from behind.

It turns out that’s not realistic because that requires exact line up.

So that there’s a perfect geometry of all sight lines that go around.

Most things don’t line up exactly, but when we do find them sort of line up, even if not exactly, you find distortions that resemble rings.

They’re arcs.

They don’t make a full ring, but they make arcs.

Now, if you have one object behind, that object will make a minimum of three images.

One that comes straight through and then two that come around the side.

And up from there, it can make three, five or seven images.

So yes.

In fact, we did see something cool.

You ready?

Okay.

So we found objects, quasars, whose light bent around galaxy clusters that were sort of midway, right?

From Einstein’s gravity.

But the path lengths were not the same.

Okay?

So the path on one side is a little longer than the path on the other.

You know how we know?

Because quasars vary.

They have explosions.

The light varies.

So we see it and it varies up here.

And then a scheduled time later, it varies over in exactly the same way.

So you get to see the same event twice.

That’s because of the change in intensity of light through the explosion?

Is that what’s happening?

Well, no, there are things…

Yeah, the quasars can eat things episodically.

A lot of weird things, episodic things that can happen in quasars.

But the fact that you have two different path lengths is extraordinary testing of the shape of the curvature of space and how much gravity is in the cluster and how far away the quasar is.

It’s an amazing thing.

It’s funny to me that you’ve come back to this because this is what my daughter works on.

We talked about the cells behind me.

But when you have rings of matter around rotating black holes…

Chuck, he’s just giving equal time here.

Because he didn’t want to pick his children.

He’s a good dad.

He’s a good dad.

Go on, good dad.

But when you have rings of matter that glow around spinning black holes, you can actually see the backside of the ring because the gravity bends the light from the growing light.

That’s what a daughter works on.

Yeah, that’s very cool, man.

One last quick one.

And we’ve got to call…

We’re over time here.

Go ahead.

This is from Glenn.

He says, Dr.

Gates, do you think that white holes exist?

What was Einstein observing that gave him the impression that they did?

All right, now I’m just going to answer this for you.

No, there are no white holes.

Einstein was racist like everybody else back in that time.

And just couldn’t let it be just black.

Couldn’t just let it be a black hole, could you?

So, no, go ahead.

Of course, I’m…

Chuck got right off his chest.

You know what?

Here’s what I love about the professor.

He’s sitting there like, I have nothing to do with this.

Whatever Chuck is saying right now, that’s his crazy business.

I only just met Chuck.

He’s like, I don’t know this man.

All right, go ahead.

Sorry.

Okay, so…

Make it quick, Jim.

Yeah, so what’s really interesting is black holes aren’t black.

It turns out that because of Stephen Hawking, we know that they actually had this very slight radiation called Hawking radiation.

So they’re not exactly black.

That went out a long time ago.

So, you know, got to keep up with the news and physics.

Okay, but the white hole concept…

The white hole concept…

I…

People who…

Look, I don’t know any solid scientific arguments about the existence of such things.

I have not encountered.

Okay, and plus we don’t see anything in the universe that would resemble what a white hole would be predicted to be, which would be the mathematical opposite of a black hole, right?

So everything is spewing out, and that should look like something in the signature of light.

We don’t see it.

Yeah, but we really got to cut it there.

Jim, okay, we got to get you back for nine other subjects.

That’s okay, Neil.

I’m game.

We got you on the rolodex.

I got game.

All right, and we’ll get a picture from your other child, your twin child behind you on the next program.

Okay, black holes, man.

Black holes.

Chuck, always good to have you.

Always a pleasure.

All right, this has been StarTalk.

I’m Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, as always.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron