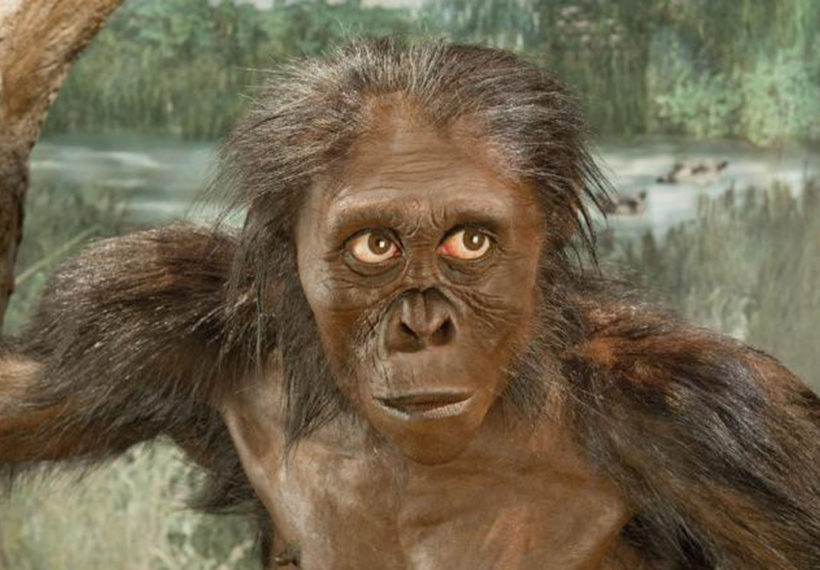

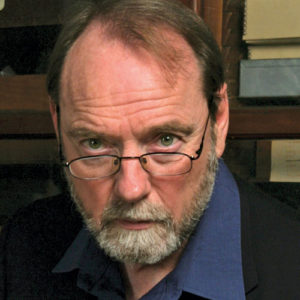

Paleoanthropologist Dr. Ian Tattersall of the American Museum of Natural History is back in the studio to help Neil deGrasse Tyson and Eugene Mirman answer fan questions about where primates came from, and where we’re going. Find out why we’re biologically static, evolutionarily speaking. Learn why we can’t simply “flip a switch” in our genome to breed children with wings. Explore the impact of technology on evolution and of space exploration on speciation. You’ll get answers to questions like, “If humans evolved from monkeys, why are there still monkeys?” and “Are we interfering with evolution by keeping the weak alive?” Neil, Eugene and Ian discuss selective breeding vs. evolution, whether different species of ape can interbreed, the difference between human hands and ape hands, and whether other primates use spears and slings. All this plus the competition between Neanderthal and Homo Sapiens, primates in space and science fiction, legislation and primate rights, and what species Eugene Mirman evolved from.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Now. This is StarTalk. I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist. In studio is Eugene Mirman. Eugene. Hello. You're a funny guy,...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Now.

This is StarTalk.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

In studio is Eugene Mirman.

Eugene.

Hello.

You're a funny guy, Eugene.

Thank you.

Anybody ever tell you that?

I've heard it occasionally, mostly my mom, some people on the web.

A couple people.

You're extremely knowledgeable, as well as likable.

Couple of people on the web.

Today, we're doing Cosmic Queries.

Cosmic Queries, themed to evolution.

Yeah.

Evolution.

Now, stars evolve, the universe evolves, but that's generally not what people are gonna be asking us about.

No.

So I did not wanna do this alone.

I gotta get back up on this.

So I comb the holes of the American Museum of Natural History and found one of its leading evolution experts, and he's a paleo-evolutionary.

Paleoanthropologist.

Paleoanthropologist.

Something like that.

Dr.

Ian Tattersall.

Ian, welcome to StarTalk.

Hello, thanks.

And thanks for joining us for our Planet of the Apes show.

That was good to have you on there.

Oh, that was fun.

And now we can take it to a new place, finding out all about evolution in humans and all the like.

Ian, you've written 20 books in your life.

What'd you start when you were six?

No, I've just been trying to catch up for the last 30 years.

All right, 20 books.

And your latest one, How We Became Human, what was that, did I get that right?

The latest one published was called Masters of the Planet About How We Became Human, trying to explain how the human species emerged.

How we emerged, okay, I might have some questions about that as we go on.

But what we do for Cosmic Queries is we solicit questions from our fan base, it's Twitter and Facebook and wherever else on our website.

And I've never seen the questions, Ian certainly hasn't seen the questions.

Eugene, you have plucked these from the ether.

I have.

Go for it.

All right, Levi Matamonowick wants to know, if human evolved from monkeys, why are there still monkeys?

It's a classic creationist argument, blah, blah, blah.

Anyway, why are there still monkeys of humans?

Yeah, Ian, Ian, we got you there, Ian.

Well, humans didn't evolve from monkeys, otherwise it's perfectly correct.

We have a common ancestor.

About 30 million years ago, monkeys went their way and we went ours.

And then something like 10 or 12 million years ago, the orangutan went its own way and we continued on our way, along with the ancestor of the apes, of the other apes, and eventually differentiated about seven million years ago.

So what's the last ape we split from?

The last ape we split from was the common ancestor of the bonobo and the chimpanzee.

Oh, okay.

And then they were like, we're gonna be awesome chimpanzees and we were like, we'll be people.

Yeah, basically, basically.

But don't, why didn't those chimps realize it's much more fun to be people?

So maybe it isn't.

Maybe it isn't.

It would be actually a lot more fun to be a chimpanzee if there weren't any people around.

Yeah, but given that there are, it's definitely more fun to be a person.

Right now, I would say that the advantage is with us.

Yes, for now.

We only have ourselves to blame at least.

But we saw the movie.

It's only just for now that the advantage is human.

It's true.

Next one, Eugene.

All right.

Lance Elliott wants to know, beyond natural selection, we also have artificial selection, such as what we've been doing to dogs for centuries.

Does selective breeding do the same as evolution faster or not at all?

And if it does cause evolution faster, could we possibly selectively breed chimps until they reach intelligence?

Ooh, yeah, why aren't we doing to chimps what we're doing to dogs?

Yeah, and creating super chimps that we can murder us.

Yeah, we already have ourselves, and I think that's probably enough for us to have to deal with right there.

Why you would want to turn a chimpanzee into a human being when human beings are already out there really messing up the world, I can't imagine.

What's the difference between buying a cake and making a cake?

You can see the fun.

Well, I suppose.

No, we're not turning chimps into humans, we're turning chimps into smart chimps.

Yeah.

Turning chimps into smart chimps.

People have been trying to do things to teach chimpanzees language.

Turns out that chimpanzees can learn a lot of signs, they can manipulate symbols in their minds, they can add them up anyway, but they just don't manipulate information the way we do.

Excuse me, Ian, by the way, Ian, neither are wolves cuddly lap creatures, but we turned them into, we turned wolves into cuddly city dogs that sit on your lap during dinner.

So why can't, why aren't we doing that to other animals, to chimps?

I think dogs basically domesticated us.

Dogs are basically the victims of their own personal kind of relationship with human beings.

Chimpanzees aren't that way.

Meaning dogs decided they could get food easier if they just hung out with us than hunted it.

And didn't bite us.

And didn't bite us.

That's basically it.

And chimps are like, we can get food easier if we stay away from people.

Exactly, exactly.

Next question.

All right, Elad Avron wants to know, Are you doing your best to pronounce these people's names?

I don't, I'm not sure.

Oh, how would you pronounce Elad Avron?

Okay, go on.

Go on.

I feel like I am.

All right.

I mean, it's spelled J-E-F-F.

Elad wants to know, Do you think it's appropriate to say that our technological advancements are part of our evolutionary path?

Did we change or cheat evolution by enhancing our lives with technology?

Or is the mere fact that we are able to invent that technology a part of our evolution?

I'm with, what's his name again?

Elad.

I'm with Elad on this.

But we are humans, we are fleshy things, and we create skyscrapers and subways and airplanes and spaceships.

So that's our world.

I think Elad has a really good observation here.

And I think that basically we have a long, long history of biological evolution.

But I think right now, all the action is on the cultural level.

It's on the technological level.

I don't think we're going anywhere as biological creatures, but boy, we're having a hard time keeping up with our own technology.

Yeah, but we've got people in the lab stirring our genome.

Why isn't that just right on the next headline?

You can stir up the genome all you want, but you need to keep it into a separate, inside a separate population.

I mean, you can get into some pretty morally hazardous scenario.

What you're saying is you can mess with the genes, put them on an island and let that gene propagate.

But this is an immoral experiment.

Like the Truman Show.

Like the Truman Show.

There you go.

All right, next.

We got like 30 seconds.

Wait, you got a quick one?

Well, Philip Verossi has a, does technology affect or hinder evolution since we as a species are able to protect our weak who may host?

Great question.

People who would have otherwise died out on the Serengeti, we keep alive till they're 80.

What's up with that?

I think basically we are-

No time.

We'll be back.

When we come back to StarTalk, we're gonna find out the morality of keeping weak people alive when we return to StarTalk Radio.

When return toTalk Radio When return toTalk Radio.

When we return toTalk Radio.

When we return toTalk Radio.

When we return toTalk Radio.

When we return toTalk Radio.

When we return toTalk Radio.

When we return toTalk Radio.

StarTalk, Cosmic Aquarius.

Oh, lemur, he studies lemurs.

Oh, yeah.

In case you didn't know.

Everything we know about lemurs is from the movie Madagascar, just so you know.

Everything he knows, and I haven't even seen the movie.

So this week, we had a cliffhanger here.

Yeah, so Philip Vasari, basically he's like, why do we keep weak people alive?

Yeah, so we interfering with evolution by bringing the miracles of modern medicine to keep people alive that would otherwise be dead or enable people to procreate who would have otherwise been impotent.

Well, you know, as long as we're able to do it and we're able to afford to do it, what difference is it gonna make?

We can compensate for some basic biological problems.

So we're rising above the limits of biological evolution.

And as soon as we cease to be able to do that, selection will take over and we'll go back to the status quo.

Yeah.

That's a pretty straight answer there.

Also, some of those people might end up being really great musicians.

You never know, it's worth it.

It's true.

It's true.

Thank you.

Cedric wants to know.

Does Cedric have a last name?

Nothing goes by you, yeah.

Eviele.

Cedric Eviele, okay, go.

Cedric Eviele probably wants to know.

Do you think that the evolution of technology is a continuation of our biological evolution?

That is another really good question.

Yes, it is in a sense because it's biologically enabled.

I think our biological evolution, as long as we're a huge population like we are today, it's not going anywhere, but you can see change all around you on the technological scene, and this is where the action is gonna be in future.

Okay, just to be clear, when you said we're all here together, there's a deep implication there.

We're not spawning branches of ourselves that could then speciate differently.

We're all interbreeding, so we're in this together in the same sandbox.

Totally.

Is that a fair characterization?

Absolutely.

So because of that, what can we do for ourselves?

We now evolve our technology.

Exactly.

Okay, all right, cool.

All right.

Cool.

Ian, Ian knocking them out.

Fernando Soares wants to know, in current human populations, a clear selection pressure isn't it?

Fernando Soares?

What does that name say?

Where's his name?

Right there.

Yeah, Fernando Soares, okay.

What?

I thought maybe you put some accent in it.

Fernando upright.

What's his question?

Go, what's his question?

Sorry, no, Neil, how would you pronounce S-O-R-S?

I'm curious.

Oh, interesting, okay.

I might say Soares.

Fernando Soares.

You might.

Okay, go.

I'm pretty sure he's from Jersey.

Anyway.

We're from Jersey, all right.

All right, anyway, in current human populations, the clear selection pressure isn't observed for certain genotypes over others.

Most people can leave offspring.

How will this affect human evolution?

Well, as I was just saying, I think it means that we're not going anywhere biologically.

That essentially that we're static biologically until demographic circumstances change.

But meanwhile, there's a lot going on in the cultural sphere to keep us amused.

So you're saying the X-Men franchise isn't totally realistic.

Totally unrealistic.

Wait, wait, wait, wait.

So what that says is because we all interbreed and we have airplanes to do it all around the world.

The next time we-

That's why we made airplanes to fly around having sex.

We didn't want, there was no branch of the human species unmated with.

As soon as we have the airplane, everything possible happens.

Exactly, but you also spread disease faster.

Absolutely.

At jet speed.

But, so it means if we speciate, it's gonna be because we send colonies to Mars or on generational ships to other star systems.

Well, you're not gonna like this because I think yes, but theoretically you could send a colony into Mars, which was small and genetically unstable, could incorporate innovations and could speciate.

But they'd be so far away that they would have no relevance at all to what was going on on Earth.

What do you mean?

Mars is a long way away.

Yeah, but what if they came back and they were like.

Ian, that's no different from Australia breaking away from its other mother continent and generating these weird marsupial creatures that you don't find anywhere else on Earth.

Same difference.

Yeah.

We weren't around to see those strange marsupials either until of course the Aboriginal Australians got there and made them all extinct in a hurry.

The fact is that we are here on Earth and we are on this planet.

As you say, we're all in it together.

You send out a colony to Mars, it's so far away.

That's what they said about Australia.

Australia.

Okay, so in 100 years as a wormhole, I get to Mars for lunch.

It's not a convincing point to me.

When Mars, when you can get to Mars for lunch, that'll change the rules.

But right now, how long does it take to get to Mars?

How long in a?

The fastest, nine months is the fastest.

Nine months?

So you could totally go there and have sex.

In fact, if you had sex and flew there, you'd have a kid.

You'd have nothing much else to do on the way there.

It's true.

Well, you could bring a Vectrex, you could bring video games.

All right, Nick Mills wants to know, oh, well, what species do you think Eugene Mirman evolved from?

Do you think they may still exist and evolve into more Eugene Mirmans in the distant future?

Well, no, let's think of this.

I think that's a question for Eugene Mirman.

Yeah.

Well, let's think of this.

He's a comedy guy.

He wrote his college thesis on comedy.

So, yeah, yeah, yeah.

You can study anything now.

Welcome to America.

You can do that.

And so, if he marries a comedian and they have offspring, what, is the genome so randomizable that these kinds of experiments are not interesting?

The genome is totally unpredictable.

It's like the lady who came up to George Bernard Shaw and said, we should get together with my beauty and your brains, it'll be fine, be great.

And then he said, well, what about if the offspring gets your brains and my beauty?

So you never know where all this stuff is going.

Right, anyway, yeah, I am very special, so thank you, Higgins.

Okay, Bill Straight wants to know, I've heard some tribes of primates go to war with other tribes.

Some have invented spears and slings.

Do we have any way of knowing how long it might take them to move up to more advanced instruments of war?

I like to think of that question as they've got something.

Does the next generation of chimps see that and then improve upon it the way we do in our libraries and our shared information?

Well, there are no other primates with spears and slings for a start.

So Bill Strait is a little wrong.

What some chimpanzees do is pass along.

We're primates and we have spears and slings.

We have primates, but we are the only primates that do.

Okay, so the rest of the primates don't, never had spears and slings?

Nope.

Okay.

Okay, and they don't have spears because they can't throw?

It's interesting, chimpanzees, for example, they've got, they have elbow, I mean, sorry, shoulder joints, which sort of aim upwards.

And although they can actually throw fairly accurately, or they can throw something in your direction and it'll pretty much land in your direction, they can't throw very hard.

They're very strong, but they can throw things very hard.

So even with their long arms, they would never make a good major lead pitcher?

They'd make terrible pitchers.

Much better to punch.

Chimps are much better punchers.

All right, Spike Mike wants to know, can different species of apes interbreed?

And if so, will their offspring be fertile?

I am asking because I worry about the Bush family.

I wanted him to say, I'm asking for a friend.

Can different species, basically can different species of apes interbreed?

Well, we all have things that we worry about.

The basically, different species of apes today do not interbreed.

Can they?

Could they?

Nobody has tried.

Nobody knows, I think, I'm not sure if anybody's tried breeding bonobos with chimpanzees.

They might have interbreed in the old days, before it was recognized that they were different things in zoos, but I don't know about that.

But that would scramble the genome at that point.

It would scramble the genome in a minor way.

The thing is, would an offspring be fully functional with either parental group?

And the question is, we've got no idea.

Okay, the answer is rather, yeah.

Interesting, so you have two different species, they'd have offspring, and it's a question whether that offspring could mate back with either one of the branches.

Yeah, you could be incompatible at many, many different levels.

You might not be able to form an embryo, for example, or you could bring the embryo to term and it wouldn't live, or it could live to adulthood and not be fertile, you know.

A lot of genetic landmines in there.

Yeah.

Interesting.

Okay, 30 seconds.

Okay.

To get another question.

Danny Hughes wants to know, shouldn't other primates have rights?

Okay, they're so almost human, should, yeah.

Yeah, why don't we let them vote?

Or better yet, have an attorney.

Why don't monkeys have more, apes have more attorneys?

There are attorneys that believe that apes should.

You know, the attorneys are very opportunistic.

But if they need, they need human beings to represent them in any kind of human environment, and so it's pretty hopeless.

Okay, when we come back, more of Cosmic Queries.

We're back to StarTalk Radio's Cosmic Queries.

So Dana Hughes asked, shouldn't other primates have rights?

But they partially do actually, right?

Do they have rights different from other animals?

There is legislation in various countries protecting animals, other primates, for example.

There's legislation in this country, which has just decreed that chimpanzees should no longer be used in medical experimentation and so on.

So yes, in a sense, they have rights, but rights is a human notion, and rights are what humans give other animals rather than something inherent to them themselves.

Just to paraphrase what you said, Ian, the rights we give chimps is laws that prevent us from killing them.

Yeah.

That's the right.

So we can give them that right, but we can't give them the right to happiness or a house.

You could give them a right to a decent existence.

If this was your judgment, it would be a wonderful thing to do, but you can give them rights to things that they cannot themselves conceive of, like to enjoy the metaphysical works of Marcel Proust or something.

I like that you're like, you can't do that.

But they wouldn't even really be able to enjoy even a shorter book.

This is true, too.

I bet that totally get into Curious George.

That would be the total bestseller.

And they might like the beetles.

But in nature, might is right, unfortunately.

They like the monkeys, of course.

Oh, yeah.

They might.

And human beings are the bullies on the block.

Yeah.

Next question.

Okay, Matt Ellie wants to know, Arthur C.

Clarke wrote of primates in space to help with tasks.

Do you see some primates possibly evolving with humans one day to make a home in interplanetary or multi-planetary cohabitation?

I don't like to answer this one under the BDI over here, but in fact, all the roles that are needed in space are much better done by instruments and robots anyway than they are by human beings.

Maybe he wrote that before robotics had really taken hold.

We don't have monkeys right now doing traffic stops or anything.

Doing anything.

Yeah, so I feel like the same way we don't, we wouldn't fly them into space.

I bet he wrote that after ham flu in those early chimps in the early space age, because you train them to hit some buttons and maybe that was his concept of the day.

They actually had to hit buttons while they were out there?

I thought so.

Maybe, I don't know.

I was kidding.

That's what I thought, that it would turn on and they'd have to react.

Really?

Because they'd be reacting under conditions that a human would then have to react under and they're just checking it.

But I think, you're right, we're way past that.

Yeah, yeah, exactly.

But he doesn't know it, poor Matt.

No, he doesn't know it.

Arthur C.

Clarke didn't know it at the time he posed that question.

All right, next.

Okay, Alfred C wants to know, in Rise of the Planet of the Apes, the primates are exposed to a drug which increases their intelligence, allowing them to be more creative and even speak like humans.

In order for this boosted intelligence to pass on to offspring, wouldn't the drug have to affect and change the primate's DNA?

Is it possible for a drug to alter DNA?

Well, this is true, and there are lots of drugs out there.

Planet of the Apes is true.

You've heard it here on StarTalk.

There you go.

I'm gonna start taking Alzheimer's medicine tomorrow.

There's lots of drugs out there that will damage your DNA.

There are no drugs available that will have this particular effect on your DNA.

Wait, but there are drugs, so you could, would drugs alter and affect DNA?

Theoretically, I suppose you could.

Wait, wait, so it would alter your DNA such that you could reproduce with that alteration?

So it wouldn't be just a local set of changed genes in your body?

Oh, well, look, I mean, there is, your DNA is a very fragile molecule being damaged all the time by cosmic rays, by you know, you name it.

Fantastic Four is realistic.

So it's, the effect isn't realistic.

Spider-Man is real.

You could realistically hope to damage your DNA.

So it's easy to damage DNA, but hard to become superhuman.

I would think so.

Yeah.

Oh, well, can't have everything.

Okay.

John Anderson wants to know, why did humans acquire thumbs through evolution and monkeys were never able to, and is having opposable thumbs the reason why our DNA is 2% different than a monkey's DNA?

Wait, they got opposable thumbs, don't they?

Yeah, monkeys have opposable thumbs, but they're not opposable in the very precise way that our thumbs are opposable.

Ian is right now tapping each finger with his thumb.

So they can't hold a gun, but they could maybe hold a rock or a mug, could they hold a mug of coffee?

They have the power grip, but look at our closest relatives, the apes.

Their hands are long.

They're long and thin.

The axis of the hand goes straight up the arm.

Our hands are totally different.

Or stubby things, compared to those.

The axis of our hand goes across the palm, and it's a different kind of a hand, and it can do different things, and it's something that just happened in our lineage, and didn't happen in the lineages leaving the monkeys or...

Wait, so is the problem that the monkeys don't have a space program, that their hands can't build things, or that they're not smart enough to do so?

It's an amazing thing that we actually have brains that want us to go into space at the same time as we have hands that allow us to build instruments.

So monkeys want to go into space, they just don't have the thumbs for it.

There you go.

I don't think monkeys want to go into space, frankly.

Show me a monkey that's really anxious to go into space.

The only ones that have been in space are ones that were sent there involuntarily by the Soviets in the 1950s, right?

How do you know it was involuntary?

Plus, I think there was an episode of Curious George in the Soviet Union where he went involuntary in the 1950s.

That's true, I can say that's accurate.

I think there was an episode of Curious George where he went into space.

I'm pretty sure.

You can draw a monkey that wants to go to space, that's for sure.

No one's saying you can't do that.

But when we come back more of StarTalk, Cosmic Queries, Evolution Edition.

We're back to Cosmic Queries.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

In studio, Eugene Mirman, and my friend and colleague, Ian Tattersall, expert on apes and monkeys and lemurs and stuff like that.

That's on your business card, isn't it?

If I had a business card, it probably would be.

I put the lemurs first.

Lemurs first.

And like I said, everything I know about lemurs is from the movie Madagascar.

So I hope, are you proud of me for that?

I know probably even less.

So we're Cosmic Queries, Evolution Edition, go for it.

Okay, Anthony Kelly wants to know, what were the influences in human evolutionary history that enabled us to develop intelligence and an ability to use tools and control environments in such amazing ways?

Yeah, what's up with that, Ian?

You know, there is no Nobel Prize in paleoanthropology, but if there was one, whoever could answer this question, especially briefly, would probably win it.

It's a very long story of seven million years of evolutionary change, leading from something that was broadly like a chimpanzee to something that we see around us today.

And a lot happened in that short time.

I don't even know where to start.

Well, let me ask you this.

That's seven million years, and we go from whatever we were to what we are now.

In another seven million years, can we somehow selectively breed ourselves or take chemicals or stir our genome to become even smarter?

I think that's unlikely.

The fact is that evolution occurs.

Evolutionary change occurs mostly in very small populations.

Small populations are genetically unstable.

New things can become incorporated in them.

Like if you stranded a branch of humans on an island or a continent, and no one inter breeds with them for millions of years.

We don't know how long it would take, but in principle, yes, if you have a small population on an island, it's almost certainly going to incorporate evolutionary novelties, because these novelties keep on spontaneously appearing because of spontaneous changes in the DNA.

But you don't see humans evolving significantly.

We won't have wings in say 30 to 50 years.

Or a million years.

Certainly not in 30 to 50 years.

But the fact is that we are now this gigantic population worldwide that Neil's already talked about.

And in a population this size, it's practically inconceivable.

You could have the fixation of any meaningful, new kind of biological adaptation.

I got a question.

I got a question.

If we have so much DNA in common with all the other life, starting with chimpanzees going down the list, presumably we have vertebrates, so we have DNA in common with all vertebrates at some level, correct?

You got 60% of your DNA in common with a banana.

With a banana.

Really?

So therefore.

So why am I not as delicious?

See, why are you not appealing?

Actually, I take it back.

I am as delicious as a banana.

Yeah, and you're appealing.

So, can I get some props for coming up with that?

That was very good.

Thank you.

That was, I will.

So, Ian, what I ask is, can't you just go into our genome, flick a switch, that excites or turns on or off whatever combination necessary, to have your offspring, have your arms have become wings?

Yeah, or have people.

If it's all there.

If you knew what to do, you'd have to do it in 7 billion people.

No, no, not in the lab.

I would be happy with five people with wings and four that were bananas.

Why do you have to change everyone?

Where would you keep them?

Where would I keep four people with bananas?

You wanna turn people back into bananas?

I don't wanna turn people a little.

I mean, I only found out recently it was possible.

So I'd like to try it just on one person.

Holy moly, this is interesting.

I'm assuming nobody wants to turn their offspring into bananas.

I wanna know.

We would force them.

So Ian, in the old days we had computers and they had what was called dip switches where you can change the parameters of the calculation.

If you're old enough, you remember that.

So if such switches exist in our genes, it's not that you have or don't have the gene.

The gene is manifested or not manifested in its operation within you.

So in principle, let's turn on the gene that can regenerate limbs as newts do.

Let's, you know, newts got that.

And here we are thinking we're evolved in some special way and we can't do stuff that other animals can do.

You know, you don't have a technology to do that right now.

We have to worry about this and this one down the line.

But right now you can repair genes, you can insert genes, you can do all sorts of things, but you're not gonna get a separate population going on its own evolutionary trajectory without isolating it somehow.

And that would be probably unacceptable to the majority of people.

Yes, let's not enslave a banana people.

And make them have wings and regrow limbs until they destroy us.

No, I want a flying banana.

That's what I want.

I kind of want a flying banana.

Flying banana, and I'll see how we could do that.

That can regrow.

We really have solved a lot of stuff here.

It could fly, people would eat it, it would regrow another banana.

Did we only get to one question in this segment?

Yeah, but it was a long, solid question.

Bananas need help.

This is StarTalk Radio, the Evolution edition of Cosmic Queries.

When we come back, it'll be the lightning round on Evolution.

We're back for the last segment of our Cosmic Queries Evolution Edition.

I'm Neil, Eugene across the table for me, and Ian is our expert on evolution.

Eugene, you have one last question before we did the lightning round, what is it?

Yes, here's a question.

What is Dr.

Tattersall's opinion on the theory that Neanderthals slowly died off because of competition with Homo sapiens?

Ooh, competition, that would be competition for food or they just slaughtered?

It could be competition for food, it could be competition for space, it could be competition for anything.

But I believe that any chimpanzee would tell you that Homo sapiens is bad news.

And I'm pretty sure that any Neanderthal would have told you the same things.

So the Cro-Magnon, I guess, were the ones that kept going after that.

The Neanderthals were living in Europe and Western Asia until about 40,000 years ago, when all by themselves mined in their own business until Homo sapiens showed up.

Within 10,000 years, they were completely gone.

It was not a coincidence in my view.

So they weren't just cross-bred and we lost the species distinction, they just died.

Basically, yes.

So I think there may have been a bit of Pleistocene hanky panky going on there, and the latest genomic data seems to indicate a slight amount of interchange of genes, as all the mayhem was happening.

That's a new move, the Pleistocene hanky panky.

Yeah, I hope one of your books has called that.

You know, that's a brilliant idea.

So you think they waged war?

Waging war?

I don't know.

We have no evidence that would.

But I can imagine, knowing how Homo sapiens tends to treat members of its own species, let alone members of other species, I can imagine that all the encounters between Neonatiles and modern humans were happy ones.

Right, considering one is dead.

It's extinct.

All right, let's lighten the round.

But just to clarify, and they buried their dead, the Neonatiles?

They did, they did.

And interestingly, the very first humans to come into Western Europe were the Neonatiles.

It apparently didn't.

They may have even learned this from Neonatiles.

All right, we're about to go to the lightning round.

We have a bunch of questions left and only three and a half minutes to do them in.

Ian, I briefed you on the lightning round.

Okay, are you ready?

Here we go.

Rachel wants to know, do we know what type of primates humans evolved from?

Broadly speaking, yes.

Neither apes nor humans, but something with characteristics of both.

Oh, next.

Fernando Translavia wants to know, if we did in fact evolve from monkeys, what is the reason we lost all of that hair that they had?

We didn't actually evolve from monkeys.

We have a common ancestor with monkeys, but I don't think humans actually lost their hair or lost their ancestral hairy cover until they moved out into the savannas about a couple of million years ago.

So a combination of coats and deserts.

Coats and desert, there you go.

I don't want enough people with hair.

You don't want to wear a coat in a desert.

There are enough hairy humans out there that that question doesn't apply to all.

Okay, next.

Okay, Lynn Olipka wants to know, why do you think there's a lack of evolution evidence within the fossil record?

It takes a lot of work to become a fossil.

There's actually a lot of-

Not everybody can become a fossil.

No, this is true, you try it.

Lightning round, keep going fast.

Oh, you won the rest of the answer.

The rest of the answer would be we actually have a very good fossil record.

Okay, but it's very hard to make a fossil.

But it's hard to become a fossil.

What fraction of all dead animals become fossils?

That is impossible to say, but way south of 1%.

Gotcha, next.

Dinosaurs died randomly.

Since that may not have happened elsewhere, should we adjust SETI for reptiles?

Should we just what for reptiles?

SETI, the search for extraterrestrial life.

Should we be looking for smart lizards?

In other planets?

That's what I'm assuming the question is.

Oh, I was thinking maybe other planets also had dinosaurs, but they would not have died from an asteroid.

Exactly.

And so they're smart, you know.

Who knows what's happening on other planets?

They're so far away that we don't know.

Let me ask the question differently.

If the asteroid didn't come and the dinosaurs were still here, might they have evolved an intelligence such as what humans have?

Dale Russell thought so.

You know, he imagined a dinosaur which had become bipedal because many dinosaurs were already bipedal and developed a big brain.

Who knows what would have happened?

So maybe.

Okay, next.

Julian Alonso wants to know, what is this missing link I've heard about and why is it important?

Well, if it's a link, it can't be missing.

And if it's missing, it can't be a link.

So basically.

Next.

Viv Cox wants to know, why could humans not have evolved at different places on Earth rather than one?

I love that.

Or life in general?

Could life have had more than one genesis around the world?

It's not impossible that the same things that gave rise to the life that we're familiar with could have happened on multiple occasions.

It's possible that we had multiple early bipeds, but only one lineage survived.

Okay, and Dave wants to know, do you predict designer babies becoming a reality for our species in the next 20 years?

In the film Gattaca, that's exactly what it was.

They got the best defined by the couple, the best of both genes to design the baby that they wanted.

Somebody with enough money could conceivably do it.

I don't think you'd find many people approving.

Okay, so yeah, it's possible 20 years if people become immoral.

Okay.

Oh, they're already immoral.

So it's the immoral future that you're predicting.

Ian, thanks for being on StarTalk.

Oh my gosh.

It's been fun.

Next, we gotta find a way to do three hours of this or something with Ian, because Ian is like my man.

I would love to.

Ian is my man from way back.

Ian, curator emeritus at the American Museum of Natural History, thanks for being on StarTalk.

It's been a lot of fun.

Eugene Mirman, we'll look for you.

You're still the character on Bob's Burgers.

Yes, absolutely.

Unrelenting.

Unrelenting.

All right, we're good.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

I tweet at Neil Tyson.

Find StarTalk on the web at startalkradio.net, on Facebook and of course on Twitter.

StarTalk is brought to you in part by a grant from the Sloan Foundation.

And as always, I bid you to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron