There have been so many new discoveries in science in the last few years – and you’ve asked questions about all of them. So this episode your own personal astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson and his trusty comic co-host Eugene Mirman tackle as many as they can. You’ll learn about bruises in the cosmic background radiation of the universe, using quantum entanglement for faster-than-light communication, the search for life on Mars and exoplanets, asteroid mining, black holes, universal expansion and our impending collision with the Andromeda galaxy – in 6 to 8 billion years. You’ll find out how an ion drive works, how space telescopes can use gravitational lensing to see farther into deep space, and how satellites stay in geostationary orbits. On a speculative level, Neil discusses warp drive technology, the multiverse, multiple time dimensions, and creationism.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Now. This is StarTalk. I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist. In studio with me, the one, the only, the...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Now.

This is StarTalk.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

In studio with me, the one, the only, the inimitable, Eugene Mirman.

Eugene, you're such a reliable guy for us.

I love coming in.

That's how I know so much about space now.

This is gonna be our Cosmic Queries edition.

Love these, it's our gift back to our listeners and our fans who send us questions, and they're so avid.

I mean, and we can't just let those go.

We just gotta bring them in.

We need to help them understand the world and the space.

So Cosmic Queries edition.

And for this one, we're talking about, what's the theme?

New discoveries, things in the news.

In the news.

Science in the news, rip from the headlines, science, law and order.

I haven't seen any of these questions before, so I might not know some of the answers.

I'll just tell you, skip it, go on to the next one.

Yeah, if you don't know something.

Yeah, so let's go for it.

Megan wants to know, what number am I thinking of?

No, Megan wants to know, I recently read that MIT folks found bruises in the cosmic background radiation indicating regions where our universe may have hit other universes.

How can our universe expand forever if there are other universes outside it?

Yeah, so you can expand forever and if you're in a higher dimension, if you're embedded in a higher dimension, you can expand without anybody ever bumping in anybody.

For example, consider a rubber sheet and you take a rubber sheet and stretch it.

You can make it as big as you want.

You can take another rubber sheet, put it one inch below that one and stretch that as big as you want.

Two rubber sheet universes stretching forever, never colliding, never touching one another.

But if it was at a slight angle, it would hit each.

I think what she's saying is-

Well, what I'm saying is, yes, if it's slight, it would hit, but you can even in an even higher-

In an even higher dimension.

It's just how many dimensions you embedded in.

A two dimensional rubber sheet in three dimensions, yeah, if you tip it, it'll, embedded in four dimensions, you can do this forever.

That's A.

B, if you're near another universe, the gravitational effects permeate the boundaries of your universe and can touch another universe.

So in principle, we could feel the effects of other universes embedded in this higher dimensional space that could be simply the meta fabric of the multiverse.

Right, so you're saying ghosts are real and they're people in another universe that happen to live inside your house in a rubber sheet universe.

Except I never understood why the ghosts that people see are not naked, because it means their clothing is ghost as well.

Yeah.

Yeah, why are they wearing clothing at all?

I think because they might be make believe.

That's just one theory I have.

Plus your outer skin layer is dead and your hair is dead.

I mean, if you're a living ghost, why do they have haberdasheries here?

And it's all really little, it's scary little girls.

The whole thing doesn't really come together.

Next question.

Okay, Silico asks.

Is that the cousin of Magneto?

I don't know, yeah.

It's a bunch of nonsense stuff, and now it says Alex from California.

That makes more sense.

He's asking, could in the near future, entangled particles be used for non-delayed communication over vast distances?

Yeah, so what happens in quantum physics is that particles can know about each other instantaneously at a distance.

So that if you perturb one particle, the other particle, which is entangled with it, can alter instantaneously faster than the speed of light.

Like twins across the world.

Exactly, I mean, if you wanna get sort of macroscopic about it.

Yeah, twins in the sense that one has a thought and so does the other.

Yeah, and the other's like, why does my hand hurt?

It's like, because your twin hit her hand in the door.

Exactly, or at least as people report.

Yeah, I'm not giving fake science here.

I get that it's not real.

So entangled particles communicate with one another faster than the speed of light.

It's very well understood.

It's a quantum mechanical.

And that's a thing that's real.

That's real.

It's not just like a dream everyone has.

That's real.

The problem is, if you wanna do that in any way that matters to life, like, you know, I don't know.

There are two worlds.

There's a microscopic world and a macroscopic world.

When you talk about macroscopic things and you want them to behave in a microscopic way, you want them to behave quantum mechanically, it all gets sort of averaged out.

The problem is you can have particles entangled, but so are the particles trying to entangle in a different way at a different time and all this becomes a one macroscopic classical physics problem where nobody is doing weird things like what happens in quantum physics.

So the big challenge is can you bridge the gap between the way matter behaves at its smallest scales exhibiting the tenets of quantum physics and the large scales that we are familiar with interacting and that it's no known way you can end up doing that.

And so right now it's a quantum mechanical curiosity.

Okay.

Yeah, you got it.

But great question.

All right.

So here's this from Michael.

I heard that NASA has recently shut down an ion engine.

Can you explain what this ion engine is and does and the potential benefits?

Yeah, so an ion drive is what we think of them as.

The big challenge here is chemical rockets are just.

Ugh, they're so.

They're so yesterday.

Yeah.

They're so Robert Goddard.

If somebody could build it in a farm and make a movie about it, it's that easy and that dull and old.

And the problem is not that there was anything wrong with chemical rockets when they were invented.

It's just that 100 years later, you think we'd be doing a little better now, right?

And we're not.

We have something more modern, more efficient than a chemical rocket.

And a chemical rocket is all the rockets you've ever seen.

All of them are chemical rockets.

They use chemistry, the energy contained in molecules.

Sounds like something that Thomas Edison would have done.

And how far have we come from that guy, that dullard?

So you have these atoms and they come together as a molecule.

And there is energy to be released if you break apart the molecule.

That's how all this works.

That's how gunpowder works.

That's how nitroglycerin works.

That's how the rocket engines or the shuttle works.

So it's all chemical energy being released, giving you propulsion.

Ion drives are much more efficient.

So the, what we call the impulse, the little push, the nudge that the rocket fuel gives you is much higher compared with the mass of fuel you ejected.

Mm-hmm.

All right, you look at the shuttle rockets and the plume that comes out when this thing launches, the mass of that fuel is huge.

It is, most of the mass of the shuttle apparatus is fuel.

Is that fuel?

So what is an ion engine, though?

So an ion engine, what happens is you have a gas and you ionize it, so you strip electrons off of it.

You need an energy source to do that, okay?

And then you set up a device.

You set up a device that ejects these little particles out the back of the ship or whatever is the opposite direction you wanna travel.

And so what's called a specific impulse, the impulse from the one little particle that comes out and the recoil of your ship is very high compared with the mass that came out.

It's a very efficient.

So when you strip electrons, it creates way more energy.

When you strip electrons and then eject them out of one side, which you can do with magnetic fields and this sort of thing.

The response to your craft is awesome.

The problem is it's not very large.

It's efficient, but it's not very large.

So you can only redirect spacecraft very slowly.

Could you make a gun with it?

Could you make an ion gun that shot electrons?

When we come back, we'll find out if you can make ion guns.

Guns, StarTalk Radio Cosmic Queries Edition.

We'll be right back.

We're back, StarTalk Radio.

I'm here, Neil deGrasse Tyson, with Eugene Mirman.

So we were talking about an Ion Engine, but that made me go, can you make an Ion Gun?

Yeah, you know, the questioner asked an honest, simple, innocent question about propulsion through the universe.

You have to take the idea, make a gun out of it.

Would it be better if I said an Ion Sword?

That sounds less reasonable.

I suppose you can make an, it would be a plasma gun is what it is.

You'd send plasma out at somebody.

That sounds great.

That sounds like a great plan.

If the plasma's hot enough, you can vaporize their clothing and then their skin.

Yeah, in principle.

You make it sound so evil.

And this will be like on the list of the, protected by the Second Amendment.

Yes, will be, yes, exactly.

They never envisioned the Ion plasma gun that so many haunt bears with.

The founding fathers.

Constitutionally protect your right to arm yourself with a plasma gun.

Okay, Jim Erickson, he asks, can NASA give coordinates and a precise trajectory to launch the corrupt and or science ignorant politicians into a black hole?

I think even I could answer that.

The answer is yes.

NASA could give the coordinates?

The corrupt or ignorant politicians?

But the question is actually, can NASA give the coordinates and a trajectory?

So it's like he has a rocket that he just needs.

Oh, he doesn't need the rocket.

It sounds like he has the rocket, but what he needs is just, he's like, I'm not sure where to send it to the black hole.

Like it wouldn't be enough to just send them into space with no way back.

We've got coordinates of very many black holes in the galaxy.

They're discovered by X-ray telescopes.

And so the Chandra X-ray Telescope, which is a telescope of magnitude Hubble, except it's specialized in X-rays, not visible light.

So, but people are not as cozy with X-rays as they are with ROYGBIV, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet.

So yeah, we have coordinates of black holes and there's a super massive one in the center.

So if you wanted to send people to it, that's how you do it.

However.

Yes, what's the limitation?

There's always a catch with you.

The catch is the more we want to send our politicians who are corrupt or ignorant, I mean, at the end of the day in a democracy, who voted for them?

Okay, so maybe it is the population we should be sending into black holes and not the politicians until the population learns how to elect a literate, scientifically literate politician.

So I've stopped blaming politicians long ago.

And blamed the voters.

And just as an educator, my target is the electorate, not the politicians.

That's all.

Right, right.

We have a call.

We actually have a caller.

A caller, excellent.

Yeah, let's do it.

Let's take this call from San Diego.

Okay, and who is it?

This is Jeff from San Diego.

Jeff, hi.

Welcome to StarTalk Radio Cosmic Queries edition.

So what do you got?

So my nine-year-old daughter and I want to know, now that Curiosity's been on Mars for over a year.

Wait, that sounds like it's really his nine-year-old daughter who wants to know.

Yeah, yeah.

He's trying to slide in on her genius.

Or he, yeah.

On her genius.

Yeah, yeah.

Okay, Jeff.

So now that Curiosity's been on Mars for over a year, and they found that Mars had favorable conditions for microbial life billions of years ago, I threw in the microbial life part.

Billions of years ago, do you think we'll find evidence of actual life first on Mars on one of the new Earth-like planets that they keep finding?

Oh, yeah, great question.

So if we find life on Mars, it's not gonna be like a civilization who's beaming radio waves to us.

Right, it won't be someone playing our Elvis record.

Backwards.

Yeah, because they don't get how it's meant to be heard.

Yeah, so on Mars, it's the microbial life that we're eager to find.

And to the biologist, I mean, I'm not a biologist, but I think I can speak for them when I say if they find any kind of life at all, whether or not we deem it intelligent, it would be an amazing discovery, the greatest discovery in the history of biology to find life that had formed independently of life on Earth, on Mars or anywhere else.

If there was water, it's sort of likely, right?

Well, every water on Earth, every place there's liquid water on Earth, there is life, even the Dead Sea, where people just didn't have microscopes to see life smaller than the resolution limits of their eyeballs.

And so they say, therefore it's dead.

No, you just don't know how to see yet.

All right, so whereas these exoplanets, these planets that might be in the Goldilocks zones around other stars, if we find life on those, we're not looking at it microbially.

I mean, there are tricky ways we can invoke, clever ways we can test to see if it has microbes.

We'd be looking at what are called biomarkers.

If the microbe emits methane, for example, methane is not stable on its own.

It has to be churned out by some process and life is something that can do it.

You look for methane in its atmosphere or oxygen.

Would we be able to find methane on one of the Kepler's?

With very careful measurements, we are at the cusp of being able to look at the atmospheric chemistry of planets that are orbiting other stars.

So if we find, I think it's more likely to find it on Mars, or we'll find it sooner on Mars than on an exoplanet, just because the technology isn't completely there yet.

Because we're there, we're on Mars.

We're literally digging things up, eating them.

A robot is eating them, trying to figure out if it was once alive.

Yeah, we're there.

And when you're looking at exoplanets, you gotta be really clever.

You have to wait for the planet to pass in front of the host star, and look at the light from the host star as it passes through the atmosphere of the host planet.

And if the oxygen is there, it takes away certain signature of light from the host planet, from the host star.

When you describe this, I can't believe scientists have the patience to do any of this.

This is, yeah.

So it's a great question.

Tell your daughter, thanks for getting you to call in for her, that's the question.

So tell her, probably Mars.

It's worse than that.

I lost the bet, she picked Mars.

She picked Mars, excellent, excellent.

So thanks, Jeff, for calling in.

All right, great.

All right, we got another question, are you ready?

And these are all from the internet, right?

Yeah, these questions are, these ones right now are going to be from Facebook, the website, startalkradio.net.

And if you like us on Facebook, just like us, yeah.

Yeah, yeah, if you like us in real life, like us on Facebook, I think it's what Neil means.

And on Twitter, StarTalk Radio, it's all there.

Okay, here's a question from Erosmo.

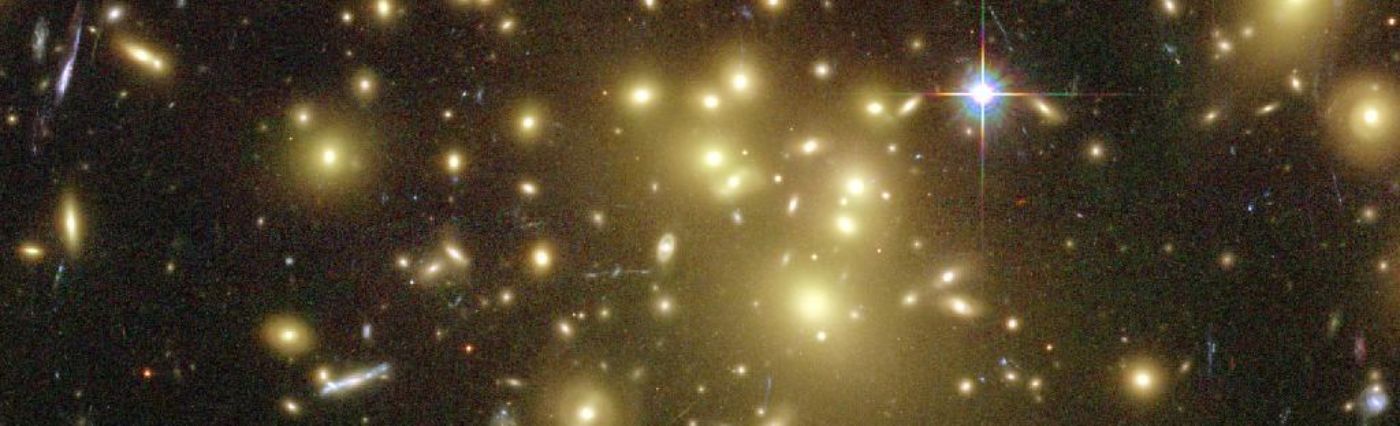

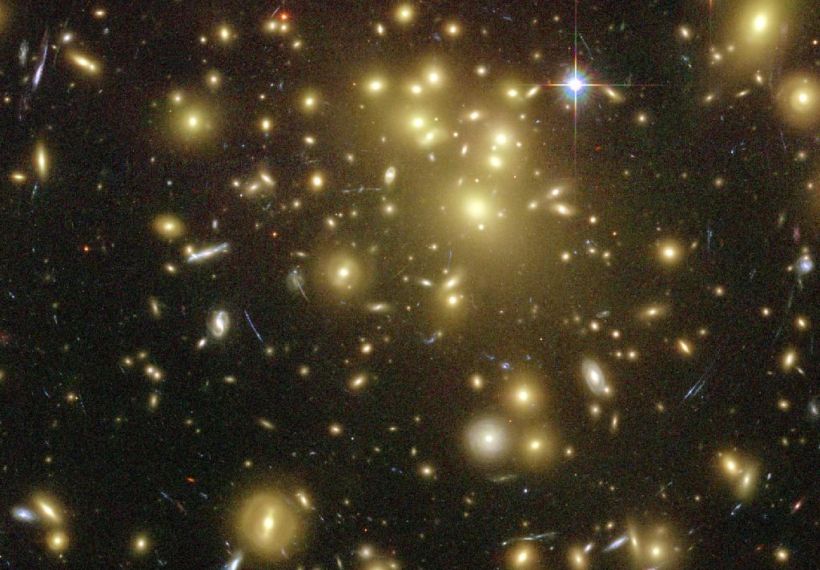

Can you tell us about gravitational lensing technology for a space telescope?

What are the obstacles and how far away are we from deploying?

Well, we know of gravitational lenses in space.

Einstein, upon discovering that gravity bends space, he hypothesized that a particular configuration of matter could bend space in such a way that it can serve as a cosmic space lens, magnifying stuff behind it in the universe.

I can't tell if you're making up science fiction or telling me information from science, because it's just on the border of like, I don't know.

It sounds like a ring powered by will.

It is all there.

And so Einstein made this prediction.

It would be 70 years or so, if I can remember my timetables, about 70 years before we would discover the first gravitational lens.

And they're all over.

They're kind of, you gotta know what you're looking for because the lens isn't just magnifying stuff in the background.

Not all the lenses are perfectly, quote, shaped to do what a normal lens would do.

Some are like funhouse mirrors.

So you can take a background galaxy and flip it left, right, up and down, distort it and make the image of the galaxy appear multiple times because of that lens.

And so previously we might have photographed it but thought it was separate galaxies.

It turns out it's one galaxy lensed by one disturbance of space time, creating this funhouse image.

So our space telescopes have found these gravitational lenses out there in space.

These aren't lenses we're making in the neighborhood.

No, they're huge scale and they require a distribution of mass that we don't have control over right now.

So how far, in how many years do you think we might?

Never.

Never, so around never?

You need the mass distribution of what you'd find in a cluster of galaxies.

Okay, sounds unlikely.

Unlikely for us, yeah, but the Borg could do it for sure.

Sure, yes, made up collective, certainly have the resources.

All right, and here's another question.

Oh, by the way, gravitational lenses allow us to see farther in the universe than our telescope might otherwise have permitted.

So they magnify it.

Yeah, they help us probe the distant universe, but we don't create them, they just.

Right, they're there.

Nature makes them for us.

Well, thank you, nature.

All right, this one's from Jamie Robertson.

Could time have more than one dimension, just as string theory requires more spatial dimensions than we experience?

Couldn't it be possible to have more time dimensions than we experience?

I so want time to have more than one dimension.

There's nothing compelling that requires us to think that.

That it does or doesn't?

That it does.

There's nothing compelling us that requires that we have to think that time has more than one dimension.

But if it did, that would just be cool.

Is it possible?

Think about it.

So if you go on to one of the time dimensions, time would ticket a particular rate for you.

Yeah, it would be four.

In another dimension, it could ticket a different rate.

And if you go in a direction that's a hybrid of each of those two directions, you would then hybridize the rate at which your time unfolds.

That's no different from walking.

You can go north or you can go east.

If you only go north, you're not going east at all.

If you only go east, you're not going.

If you go in between, you're going a little bit north.

You go north, northeast, east, south.

So you're saying there could be time that's going north and time that goes east.

In a sense.

And then you could pick a trajectory that gets you a little bit of one time and a lot more of another.

That would just be kind of interesting.

And I don't know quite how to think about that going forward.

We're not compelled to do so.

When we come back, more StarTalk's Cosmic Queries edition.

News rip from the headlines.

We're back, StarTalk Cosmic Queries Edition.

I'm your personal astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson, in studio with Eugene Mirman, who's reading the questions from the internet, culled from our fan base, our listeners, and whoever else cared to write in to our website, to Twitter, to our Facebook page, to Google+, to Pinterest, go for it.

I haven't seen any of these questions before.

I don't know how Pinterest works, but I believe you.

I haven't seen or heard any of these questions.

And the topic is science ripped from headlines.

Yes.

Yeah, yeah, so let's do it.

So here's a question.

This one is from Alejandro.

If an ancient civilization in Earth's history had made geostationary satellites, would they still be in orbit today?

Yes, there is nothing to interfere with the orbit of a geostationary satellite.

It is so far out, orbiting 22,000 miles above Earth's surface.

What would that be in kilometers, I guess?

Eight.

That's so blatantly wrong.

Let's try 30,000, no, yeah, about 30,000 kilometers up.

If you're that high up, there are no air molecules from our atmosphere to slow you down and decay your orbit and drop you into the Pacific Ocean or anywhere else.

So yes, it'll stay, it's basically will stay in orbit around the Earth forever unless some asteroid or the meteor hits it, but that would be an extraordinary fact, the dynamics are stable, we're good.

But that would not be for me the most interesting fact here.

It would be that we had a civilization from a long ago.

Yeah, that had made, that had sent something into space and we haven't found them.

Right, and where are they?

Are they underground?

So I would be way more impressed that such a civilization existed than that they put up a spacecraft.

Right, right.

All right, next.

So Ryan has a question.

How can the universe be expanding and get galaxies or swallowing each other?

Wouldn't the push be a greater force or has it slowed down?

These people are totally getting them.

Excellent, okay, so it turns out we live in an expanding universe and the farther away you are from a neighboring object, the more manifest is the expansion of the universe.

So if you are really close, the expansion of the universe is so small as to be swamped by your mutual gravitational attraction.

So we and the Andromeda Galaxy, two million light years away, we are falling towards one another, even in the middle of the expansion of the universe because we are so close that our speeds and our gravity totally override.

How quickly are we falling towards each other?

Or slowly, however you want to answer it.

So you're worried about the future of Earth.

Yeah, I'm worried, like do I have to be worried about like Thursday or like 2020?

Is it not climate change but a falling galaxy that I should be concerned about?

We will collide anywhere between six and eight billion years from now.

And the sun will die in?

Five billion years.

Yeah, so the sun is a much bigger issue of concern for you.

But presumably by then we'd be able to planet hop, find another solar system.

So it's still something to think about, I think.

And the reason why I say it's between that period of time, because a galaxy is not a single point in space.

It's a huge extended object.

So at what point are we colliding?

It's like polyphonic spree, which is a very big band, trust me.

So it takes a long time for galaxies to actually collide because they're so large and they're huge systems.

We'll likely survive that.

It'll just be a beautiful train wreck in the sky.

Stars are very far apart from one another.

So our solar system is likely to stay intact throughout this entire journey.

Enjoy the ride.

All right.

Okay, here's a question.

This is one's from Joseph.

Is it possible that the universe isn't expanding, but that we're all just shrinking at a constant rate all the way to nothingness?

Seriously, wouldn't that look like expansion from our perspective?

Wow, that's a great question.

I'd have to think about that.

Sure.

If everything was shrinking, hmm.

But at the rate the universe is expanding, I don't know.

It seems like we would have shrunk.

Everything in the universe would have to shrink, but here's the problem.

It's the universe itself that's expanding, not the things in the universe.

Right, right, we're not growing.

Right, exactly.

Except for Americans.

So, I have to think more about that?

Yeah.

I bet that'd be a fun little sci-fi cartoon.

I'm gonna say physically, based on not knowing anything, I don't think that's the case, but I like the idea.

Yeah, it's a fun idea.

I have to think about that.

We'll get back to that.

Could we be shrinking?

Could we be shrinking at a rate that appears that the universe is expanding?

Yeah, because all of our measuring rods would have to be shrinking with us.

Well, we could be.

Everything could be shrinking around us.

Right, but that'd be an extraordinary thing if it were happening.

It's not more extraordinary than just something expanding.

I mean, things expand all the time.

So yeah, pick your extraordinary explanation.

This sounds like something they would have thought in the Middle Ages.

I go with, yeah.

And then murder to anyone who was like, I don't know, I think it's expanding.

Don't be an idiot.

We're all drinking.

We're gonna murder you.

We're going to liberate your soul.

That's what that is.

Yeah, you relax.

We got time for one more in the segment.

What do you got?

Okay, Martin, he's writing from Norway.

If warp drive technology actually works and you use it, how do you know where and when to stop?

Ooh, no, you'd have a map.

You would have the coordinate system of the hyperspace through which you're traveling.

Your normal maps wouldn't work.

Excellent question.

You wouldn't use the Google Maps.

You'd be like, this iPhone can't guide me through hyperspace.

You need a map that goes to the higher dimension through which you're traveling.

And then you can land back where you were going.

So you'd first map out hyperspace and then you'd probably switch the hyperdrive on.

Then you could switch your hyperdrive and land someplace where you need to be.

And go around rocks and whatever.

Are there a lot of rocks in hyperspace?

You wanna map around asteroids and other destroyed planets.

I mean, look at this asteroid belt of Earth, I mean, of the solar system.

There's a lot of rocks there.

So you wanna avoid things that could kill you before you got to your destination, yes.

Awesome question that was.

This is StarTalk Cosmic Queries Edition.

We'll be right back.

We're back, StarTalk Radio.

Cosmic Queries edition, Eugene Mirman.

Okay.

What's your Twitter handle?

Twitter handle is at Eugene Mirman.

Eugene Mirman, okay, gotcha.

All right.

All over it.

Yeah, get on it, world.

Here's a question from Ian.

He writes, I visited the Creation Museum purely out of a sense of mystified curiosity.

The recorded narration in their planetarium claimed that contemporary astrophysics predicted that certain stars were older than the known age of the universe and cited this problem as evidence against science and for young earth creationism.

I think this was a real astrophysical problem for a while, but has since been outmoded by better models of stars.

I was hoping Neil might tell me a little bit more about the problem and its solution.

Which problem?

The problem that a Creation Museum exists at all?

I think the problem that a Creation Museum, I think what it is is it's pointing to some outdated model of understanding science.

Yes, okay, so let's unpack all of that.

So if we actually have nothing specifically against a Creation Museum, just keep it out of the science classroom.

We live in a free country, people could say whatever you want about whatever.

Just like the Batman Museum is not accurate historically.

That's what it means to be free.

Just don't confuse it with actual science.

So back, when was it, in the 90s, there were measurements, this is before Hubble, settled all these questions, the Hubble Telescope, that is.

We had measurements of the oldest stars and they were coming in 18 billion years old and measurements of the age of the universe, that was coming in at about 15 billion years old.

So that was, it was an unsolved problem in astrophysics.

I don't know, it sounds like God exists when you say that.

You can't be older than your mother, okay?

That's the, if you want to get a terrestrial version of that.

Each of those are, there was data obtained by completely independent separate methods.

So I was quite happy that they were in the same ballpark, 15 billion, 18 billion.

So a few billion here or there.

Cosmically speaking, that difference is small.

It's not one that's a thousand times older than the other.

Then somebody is not doing something right, okay?

So a few billion years on 15 billion years was, it was something, it was a problem to be solved, but it made much sexier headlines to talk about than what any, than.

So scientists were like, this all seems pretty reasonable.

With more accuracy, we'll figure it out.

Yeah, yeah, that's how we were dealing with it, and everyone was like, oh my gosh, how did you do it?

You know, cos what they weren't considering what we call error bars.

Error bars are you make a measurement and what is the uncertainty of that number?

The uncertainty in the 15 billion year age of the universe was plus or minus two billion years.

You see these error bars now, these uncertainty numbers in election polls.

So they became familiar to people.

What is the margin of error?

So now people understand that it's like, maybe it's 13 billion, maybe it's 17.

Maybe it's 17.

And now you have the 18 billion year old, a star that could be, that was 18 plus or minus two.

So the overlap in that is fine.

It's perfectly reasonable.

So the Creation Museum uses science from the 90s to prove that science is wrong.

Well, right, it's all wrong.

And the fact is in a young universe as what is put forth by Creation folk, that is a universe that's not, it's 6,000 years, no more than 10,000.

It's in the thousands, not billions.

So these are apples and oranges going on here.

So by the way, it's possible to have an error bar, an uncertainty range that is completely out of whack.

That would mean there's a systematic error in your data.

Like the way that they thought they created what, fast tachyons or no?

Yeah, that was a, yeah, that was a, felt they'd found particles in the Switzerland that were traveling faster than light.

And either it was a blunder or they were actually traveling faster than light.

And we've never ever seen or measured anything travel faster than light, which meant it was probably a blunder.

Turned out it was a blunder, just a complete blunder.

And that happens.

So back then it was a fascinating story.

So right now the universe is about 14 billion years.

The ages of stars all match up.

We have better measurements of what goes on inside of stars.

And that all got resolved.

Hubble helped out mightily in that.

So that's all that was going on there.

So now everything makes perfect sense.

All right, so let's ask another question.

Ready?

Yeah, go for it.

What is the worst case scenario for misuse of the warp drive?

Dan Owens, what's the worst case?

Quickly.

Misuse of a warp drive?

I don't even know what that means.

Anything a warp drive does is gonna be good.

So misuse would be you use it to actually travel back in time and then you kill your grandparents and then you no longer exist.

Depending who you are, maybe that'd be fine.

By the way, you don't ever have to kill your grandparents.

No, you could just push them down.

No, no, yeah, just prevent them from ever having met.

You don't have to be bloody about it.

In fact, you could go back to your great, great, great, great, great grandparents and change the time they had sex, okay?

Then you will not have been born.

You could just literally jump out of a closet and go, ah!

And then you'd probably ruin your whole timeline.

Okay, then a different sperm, a different sperm fertilizes the egg, and you're never born, okay?

Sounds like a plan.

You folks are not creative.

When we come back, more StarTalk Cosmic Queries edition.

We're back, StarTalk Radio, Neil deGrasse Tyson here, Eugene Mirman, Cosmic Queries edition, the lightning round.

The last round, this is all the stuff we, because I take too long to answer questions.

Yeah, so we gotta go super fast.

Go super fast, and let me test the bell.

You got it, okay.

You nailed it.

All right, this is from an 11-year-old, from Shani.

Cool.

She wants to know, how could there be nothing before the Big Bang?

Huh?

Excellent.

We don't know what was around before the Big Bang, and any respectable scientist will not tell you that there was nothing there.

So there might have been something.

There might have been something, and it could be the thriving multiverse that is where just one of the bubbles, and it comes and goes.

Other bubbles are coming.

We don't know.

Thank you.

There was a party.

You got it.

All right, here we go.

Theoretically.

Oh, by the way, there's an episode of Family Guy where Stewie takes his time machine and goes back to before the Big Bang.

And yeah, so what happens there?

There's nothingness there, just like she said.

There's not even space or time.

I bet there was a Doors concert.

I bet Jim Morrison is there writing his rhymy poems.

And that came about from a conversation, a lunch I had with Seth MacFarlane.

He just started asking me, oh, tell me about the Big Bang.

And I tell him about it.

And then I ended up with a screen credit as science advisor to this Stewie going back to the beginning of the universe.

That was cool.

Next.

Samuel, okay, he asks, theoretically, could wind travel faster than light?

No, next, no, I mean.

What's the fastest wind could travel?

Wind could travel like the speed of sound, all right?

That's basically.

A little Mach 2?

I know Mach 1.

I know, but I'm now upping it.

No, because it can't get past other molecules that are in its way.

So you can't have one piece of air travel fast.

No, next.

Mach 1 it is.

Okay, Austin asks, Neil, what is your favorite or in your opinion?

Wait, wait, I should say, so how fast does a molecule move?

It bumps into the next molecule and sends that signal to the next molecule.

Now you can move a whole body of air together and all the molecules are in there together.

I suppose you could accelerate that whole thing.

Could you have a hurricane that went faster than Mach 1?

A hurricane is still moving embedded within another air pocket.

Oh, sure, sure.

Put the wind in a hurricane, sorry, that's what I meant.

Yeah, right.

Okay, great.

Is Wizard of Oz realistic?

No, okay, Austin asks, Neil, what is your favorite or in your opinion, most significant space exploration related discovery of the last year or so?

Oh, so I would have to say it was not a discovery.

It was the fact that we were able to land Curiosity on Mars in the way we did.

It was an engineering Rube Goldberg nightmare that turned out to be completely successful.

And that tests all the other ways we can now land on other planetary objects.

Loved it.

It was an engineering achievement, not a scientific achievement.

Next.

Okay, Mike Ward asks, does a black hole die like stars do?

If so, what happens?

Do they go supernova and expel all the collected matter back into space?

What happens in a black hole stays in a black hole.

That's accurate though, right?

No.

Black holes actually evaporate according to a discovery made by Stephen Hawking, the University of Cambridge fame.

Stephen Hawking discovered something, today we call it Hawking radiation.

The stuff that goes in a black hole slowly evaporates out of the black hole until the black hole one day disappears entirely.

And then it's just gone.

It's gone completely.

Correct.

It's very slow, takes 10 to the 100 years to evaporate a supermassive black hole.

A Google years.

A Google years.

Yes, yes.

Sounds reasonable.

Next.

Okay, if we bring an asteroid from mining into orbit around the moon, will we be able to see it with the naked eye?

Depends how big the asteroid is, the one they're thinking of bringing in now, no.

That one is about five feet across.

You're not seeing that one.

But a big one, yeah, bring it on.

Watch it, pull out your telescope, check it out.

And you could watch people mining.

If it's big enough, what's big enough, you know.

What's big enough, two miles?

Miles across, miles, you'll do it, but not feet.

Next, yeah, lightning round, go.

How do elements heavier than iron, such as uranium, form in stars?

Oh, yeah, so they don't form in stars.

They form when the star explodes, supernovae.

There's all kinds of energy to burn.

No pun intended when a star blows up.

So iron, which the star makes after it has started with hydrogen and helium, and it goes right on up the periodic table to give you iron, to make iron in its center.

After iron, the star explodes, that extra energy continues to pump iron.

And, did I actually say that?

Yeah, pump iron, yeah, yeah.

It continues to pump iron.

It pumps particles into iron.

They march into iron and make iron heavier.

And it builds all the rest of the elements on the periodic table, right up to uranium.

Yes.

Sounds like, yeah, that sounds accurate.

You got it.

Uranium, by the way, named after planet Uranus.

Next.

Nice.

Okay, Olivia wants to know, would it be safe to live on a planet or bring a pulsar?

If so, would life on the planet be short-lived?

It is not safe.

You'll die.

Pulsars are huge radiation sources and radiation is not compatible.

High level doses of radiation is incompatible with life.

Oh, right.

Find plenty of other beautiful stars to post your planet.

Go.

Last question.

I don't know.

Go, go, go, go.

Last question.

Okay.

All right.

Last question.

We often talk about observed cosmic events as having happened in the past.

EG if a star goes supernova 10,000 light years away, you hear it described as happening having happened 10,000 years ago.

However, since time is relative, wouldn't this mean that however far away we are from an object, any event we can't yet observe hasn't actually happened?

If we are not moving significantly relative to that other object, another star sitting out in space, we're basically in the same time zone.

So we're cool.

We don't have to worry about severe time dilation.

It's relative when you're moving really fast relative to another object or place or thing, then you've got these issues.

But a star blows up in our, it's our galaxy.

We're moving together in this.

Yeah.

We're fine.

We're fine.

We gotta run.

That was been StarTalk Lightning Round Cosmic Queries edition.

Eugene Mirman, thanks as always for being on StarTalk Radio.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, leading you to keep looking up.

Up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron