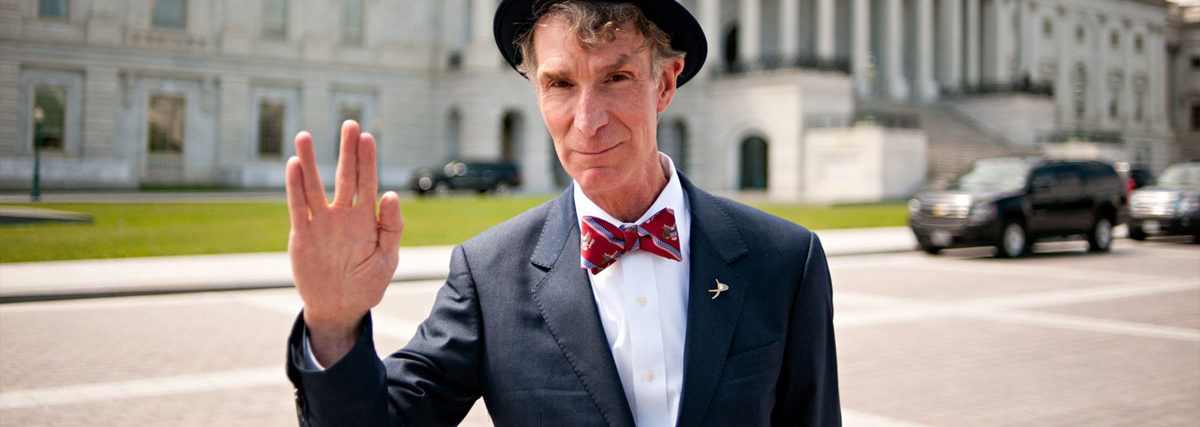

Bill Nye, CEO of the Planetary Society, is back as guest host for an episode about a subject near and dear to his heart: funding space exploration. Together with comic co-host Eugene Mirman and guest Astro Mike Massimino, they answer questions from our fans about the value of planetary science, from innovation to inspiration. You’ll learn how NASA works with contractors and why the privatization of space still costs taxpayers money. You’ll also explore why for every $1 we spend on NASA, we get back $3.60. Find out about specific programs, including Curiosity, a manned mission to Titan, crowdfunded space telescopes like the Arkyd project, the Cassini probe, robots on the moon and so much more. Mike discusses how his two Space Shuttle flights to repair the Hubble Space Telescope helped support the discovery of dark matter. Plus, the trio discusses attacks on STEM education, the lack of science coverage in the mainstream news, whether astronauts really drink Tang and how you can have the greatest impact on NASA funding.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Welcome to StarTalk Radio. I'm your host, Bill Nye the Science Guy. And with me today is Eugene Mirman. Hello Bill. Wait,...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Welcome to StarTalk Radio.

I'm your host, Bill Nye the Science Guy.

And with me today is Eugene Mirman.

Hello Bill.

Wait, where's Neil?

Neil?

Yeah.

Neil Tyson, deGrasse Tyson.

Yeah, yeah.

He's busy, he's gone.

He asked me to sit in, but I'm doing my best to have good posture.

Also with us today, Eugene, is Mike Massimino from NASA, unlike many of us, flown in space.

Call him Mass, yeah?

That's good.

Call me Mass.

Good to be here, Bill.

Thanks.

How are you doing, Eugene?

Good, good to see you, Mike.

Now Mike, you're in New York.

I am.

I'm at Columbia University.

I'm teaching a space-related course, Introduction to Human Space Flight.

Let me ask you this.

So this is the introduction to human space.

That's right.

Are there like 200, 210 to 300 level courses?

How many courses do I take in human space flight?

This is the introduction, so we'll start with this, and then we'll see how this one goes.

We're taking it one at a time.

If you take that class.

If it goes well, we'll see where we want to go from there.

Is that enough to kind of go in, like how much more than your class would I need to go into space?

You would need a lot, Eugene, but all of us need a lot.

A lot.

But this will give you the basics of what you need to learn.

Say I took your class and had, I don't know, $85 billion.

Would that to get, would those two things be enough?

With the 85 billion, you don't need my class.

In fact, I would recommend it in that case.

No, in that case, I would say don't waste your time.

If you figured out a way to make $85 million and you want to spend it on a space flight, I would go straight to that option.

Gentlemen.

Yes.

Sorry.

No, it's great.

It couldn't be better.

This is the Cosmic Queries edition of StarTalk Radio.

And we have queries from out there, from the social media.

Yes, from Facebook, Twitter, probably photos on Instagram of questions.

The Tumblr, all the things the kids are using, but they're electric computer machines.

Exactly.

College kids.

Yeah, well, we'll see.

So my understanding is Eugene, radio is a visual medium out there.

He's got some papers.

Yeah, I have some papers with questions that people wrote in about NASA and planetary science funding, and I'm going to read them.

So let's try one.

Let's do it.

Will Burke asks, what is the biggest stumbling block for NASA to get funding?

Is it stubborn legislators, science illiteracy, or other factors?

What's the best way we can change it?

Miles?

I think that NASA does get funding.

We always could use more, I think, in general.

But I think it's just how we value things.

If we would value the science that comes out of the space program more, I think people would be willing to pay more for it.

Exploration, international, I think a lot of people don't understand all the things that NASA does.

What are?

Let's just take one thing, international cooperation.

You might not think of NASA with international cooperation, but a lot of the science programs we have, particularly the International Space Station, is international.

It's called the International Space Station.

It might be very hard to make friends with a Russian on this planet, but if you just go a little into space, everybody's friendly.

Well, look about when I was a kid, we weren't necessarily friends with the Russians.

The Soviet Union and the US were in a cold war, and now we fly into space with these people all the time.

We're really good friends with them.

I think that's one benefit that people don't realize.

The other thing, everybody, for me, science is important, and I love science, I'm the science guy after all, but what the space program brings us is this optimism.

When you have a space program, no matter what country you are, you believe, your society believes, many people believe, that any problem can be solved.

If you can put a man on the moon, we can make a car that goes over 100,000 miles.

We can do anything, and this is why all these countries you might not think of, of having space programs that you fly with, South Africa, what have you, Australia, on the back of the Canadian Brazil.

Brazil has a space program?

Yeah, yeah.

Marcos Ponce, he's an astronaut.

You hear the tone of his voice.

Yeah.

He was incredulous.

Oh no, I'm not mad at them, I'm glad.

No, no, you just didn't believe it.

It's crazy, wow, yes, because they know the value of having people running around in your society solving space problems, and the thing for me, as the executive director, CEO of the Planetary Society, is-

It's a charge.

Yeah, well, is planetary science is where these new problems are being solved.

Trying to land a car on Mars is an extraordinary undertaking, and so when you go to solve problems that have never been solved before, you just innovate, can't be helped.

So that's the, the value is selling politicians of all sides of the executive, the judicial, and the congressional representative on the value of space exploration.

So that's the, because the last part of that question was what's the best way we can change it?

What are like, say, two or three things?

So voting, vote on the, the way that people vote on particular issues, vote on the issue of science.

That's right, well, especially space science.

Space science.

Yes.

So people say, why are you exploring Mars?

What are you going to find there?

We don't know, that's why we're exploring.

We're going to probably find the technology to make even better cell phones.

No, that's absolutely correct, yeah.

People do have a voice in this.

For example, the Hubble Space Telescope, which was, I think, a very good combination of human space flight and planetary science, would you agree?

Oh, yes.

All the smart people that come up with the discoveries.

I mean, it had some problems.

You had to watch the space and fix it.

That's true, yeah.

Well, they had canceled the last servicing mission that I was lucky to be on.

They had canceled it and then it got brought back mainly because of public outrage and politicians listening.

Bill, I'm sure, is a big part of that.

They wanted Hubble fixed.

People do have a voice.

If we could only trick Al-Qaeda into bombing something in outer space, we'd be there in weeks.

Well, that was what started the whole thing, was the ultimate high ground.

We digress.

So vote, person on the who asked the question, and let's change the world.

Okay, here's the next question from Chris Van Gundy.

Shouldn't the rest of the government be begging NASA for money?

Well, this is the old question.

You see, it's not do space exploration, or provide clean water for people who don't have it, or provide education for girls and women so that they raise the standard of living and improve the quality of life for all citizens everywhere.

It's not one or the other.

It's not NASA or build a new baseball stadium.

You have to do everything all at once.

Also, investing in NASA then literally has a very good return, right?

In terms of the money the government spends.

And it's not very much.

It's less than one penny of your tax dollar that goes to NASA.

Yeah, 0.4%.

And furthermore, also in addition to continue, the current number is $3.60.

For every dollar that goes into NASA, you get $3.60 back.

That's pretty good.

That's really good.

That's very good.

Some people will argue that highways are slightly larger, but highways in general do not lead to innovation the way space exploration does.

And it's some for the future.

It's about the future.

Innovation is what's going to drive the economy.

So anyway, you guys pretty soon, we got to take a break.

You sold me on it.

We got to take a break, but I want you all to out there to visit www.startalkradio.net.

Find us on Twitter at Star Talk Radio.

Check out Eugene Mirman at Eugene Mirman and check out Mike at Astro underscore Mike.

Welcome back to StarTalk Radio.

I'm Bill Nye, the Science Guy guest hosting for my beloved colleague, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

I'm here with your favorite, Eugene Mirman, and everybody's favorite astronaut, Mike Massimino.

Call him Mass.

And this is the Cosmic Query edition of StarTalk Radio, and we have your queries from the cosmos.

It is, there's very strong evidence that all of these questions are from people within our universe.

Yes.

But maybe not.

We'll find out.

Take one.

Let's go.

William Dyke asks, what are some of the current and future strategies of privatized space travel versus those of NASA or other government-based space programs?

What is different about their strategies and why?

What types of missions or projects do you see these two sides carrying out 50 or 100 years from now?

Ooh, that's a lot of questions.

People are terrified of only asking one clear question.

It's of a piece, though.

It's all one thing.

The difference is when people started exploring space at NASA, they weren't trying to make money.

The modern idea is that you could make money in space.

Now, people make a lot of money in space with communication satellites.

I don't want to shock you all, but there's this business of the National Security Agency and there's certain spy satellites and there's a lot of weather satellites and those data are sold like crazy.

There's a lot of money in rain.

Yeah, that's right, there is.

If you're a farmer, yeah, you have great fascination and so on.

With that said, there are extraordinary ideas.

Let's go get an asteroid and pull back the platinum.

Yeah.

But anyway, those people believe they can make money, but note well, a company like SpaceX or Sierra Nevada Space or X-Core Corporation, these companies take money from the US government to promote or develop their rockets.

It's not a standalone business yet.

Mass, did you get involved in that stuff?

Yeah, we work in the three of the companies that are trying to get us back with people launching to the International Space Station with astronauts.

You mentioned a couple of them.

SpaceX, Sierra Nevada and Boeing, or we have a contrast.

Sierra Nevada is not a soda company?

No, it's not.

No, it's nothing to do with beverages.

Although hopefully they will provide beverages on their spaceship.

Eventually.

You need water.

Hey, I've got a question.

Sorry, do you guys really drink Tang?

We drink what we call orange-flavored drink because the name you mentioned.

No branding in space.

Right, exactly.

So everything we have, like, let's take a chance.

Q-tip, okay?

Ah!

Is not a Q-tip, it's a cotton swab assembly.

And that's an assembly.

And what really gets us-

So is it a CSA?

It's a cotton swab, a CSA, but we wanna make sure we know what it is because CSA could also be Canadian Space Agency.

Or a community-supported agriculture.

You know what really gets confusing though?

What?

Is when you need to take like any kind of medicine or, cause it's all got that, it doesn't have the brand names.

Oh, so you don't know.

But are you allowed to bring brands into space and just not say them?

Like if you ever had a candy bar, that's a, I don't even know.

That's right.

Well, we have certain candy bars that you, we have certain candy.

It's very, very popular cause they're small and you can float them.

And we call them candy-covered chocolates.

You don't call them WWs and just like, oh my.

Oh, let's get back to this guy's question.

But everything has its generic name.

Yeah, so what are some private?

So we have a generic name for that product, which is orange flavored drink.

Orange flavored drink.

So while you're enjoying your orange flavored drink, it is to be hoped that soon you will get up into microgravity by means of rockets not built exclusively by NASA.

Correct.

And that's what, you know, NASA has worked with contractors right from the very beginning with some of the big government contractors, Rockwell International, for example.

The old joke, you got to the moon on the lowest bidder.

That's correct.

All the parts, you know, Grumman, all these companies all work together to build spaceships funded by the government.

So there is some government funding going into those private companies as well.

So I think it's a good partnership.

I think, as Bill said, they're trying to make money.

And so this could be a very, very exciting time.

And I've noticed that my position at Columbia with all these young, smart kids, and these kids are a lot smarter than I ever remember being.

They are interested in the space program just as much as we were when we were kids, but it's not just NASA.

It's they're interested in going to work for one of these companies.

I see it as entrepreneurship as the future.

And I think that there's gonna be, hopefully, if you're optimistic about it, a very good relationship between the companies and NASA in the future.

Well, NASA is a sort of launching pad for a lot of private.

A launching pad.

That's brilliant.

Wow, how'd you work that in here?

Let's try another question.

But that's the whole idea.

All right, here's another question from Susan Minnob.

People often complain about the NASA budget and claim that private industry should take over some of the work that NASA does, but they don't do it already because of government, but they don't, they do it already because of government contracts.

What percent of the NASA budget goes to private sector contractors?

That's the question.

I don't know, but it's gotta be enormous.

Whenever you buy hardware, you're buying it from companies like Boeing, United Launch Alliance, what have you.

Yeah, NASA buys stuff from a lot of companies.

But in the big picture.

Yeah, they get contractors to work for them.

They only have a certain number of people working in the NASA workforce.

How much stuff is built there?

I decide I don't know.

Let's say you have a Mars rover, hypothetically.

It's machined, the metal is cut at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, some of it.

The mirrors are coated somewhere else.

The lenses are ground somewhere else.

And these are all done by companies.

But the fundamental, if I can read into this question a bit, there's no, right now, there's no business model that takes people to Mars.

There's no business model to find out whether the core of Jupiter has hydrogen that acts like a metal.

There's just no reason for a private company to do that at this time.

Even though I'm very curious?

Well, yes.

That's not enough reason.

That don't put bread on a table, Eugene.

Well, you don't know that because you might find something about the hydrogen metal that would affect the way we make semiconductors or microcircuits or something.

With that said, these things are all built by contractors and then the crossover right now is the guys, the people who want to mine asteroids.

At first, it sounds sexy and fabulous and literally a shiny object to go to an asteroid and get platinum.

But apparently, the big thing they want to get on asteroids is water.

So you take water and then it's fuel for your spaceship to keep going.

So you have solar panels on your spaceship, your thing, your spacecraft.

You get out there into the asteroid, you electrolyze water, make it hydrogen and oxygen, somehow put it in a tank.

How hard could it be in outer space?

Millions of kilometers from here.

And then you would have fuel to go on to some other exotic destination, maybe to your platinum bearing asteroid and you drag that back to the earth and get rich.

That's a pretty good plan.

All right, so here's a question from Twitter from Michael Christian.

He asks, what kind of private donation systems exist to supplement funding NASA projects or other planetary science research?

Well, I'm sure this person is referring to the Kickstarter program for StarTalk Radio.

Wait.

Or for a shuttle.

Is there a Kickstarter to raise billions of dollars?

The only donation system I know is called Taxes.

Really?

I mean, I don't...

Wait, you can't...

But Bill probably...

I mean, as far as NASA goes, NASA gets its budget based on the tax dollars.

But the way that NPR, various places that are partially public, partially private get money, is there a thing like that where you could be like, you know what, I'm going to give $7 billion to NASA?

Well, there is one that I know of, and I'm not an expert on all of them that there might be, but the Arcade Telescope.

This is a idea where they're going to make telescopes to look, nominally to look for asteroids, but the proposal is to have one pointed at the Earth, and then you, the user, the online happy person, can get that telescope to point at anything you want.

It sounds very romantic, Mount Everest, but maybe your neighbor's yard, what have you.

Check if the lights are on when you're away.

For example.

How does, anyone can access it?

Anyone who's, I don't understand the price structure exactly, but you give so much money to ARKID, or A-R-K-Y-D, and they will give you access to the telescope based on some formula.

And I imagine.

Do you hear that very creepy people?

I don't think I like this idea.

Put in a dome over my house.

Yeah.

Well, I don't know what the resolution would be and how much value it would be, but what do you do when you download Google Earth and get it running on your computer?

What's the first thing you do?

You look at the sea where all your exes live.

Eugene, I keep some of that to yourself.

That's a warning to Eugene's exes right there.

That was Eugene.

How many were you talking about in round numbers?

A, 100 to 300.

Yeah, no, normal.

All right, here's another question.

Daniel Segraves asks, since our government doesn't understand priorities and I want to contribute to NASA financially or otherwise, otherwise, I don't know what he means, send the bones, what is the most effective way to do so?

So that's a similar question.

I would claim the most effective way is to vote.

That you hire people, which we call congressmen and senators, to make these decisions.

And you hire them to figure out where to send money to what.

So you write them letters, you call them, you could, for example, join the Planetary Society at planetary.org, and we will work to influence Congress to ensure funding for space.

What about lobbyists?

I mean, do people, are there lots of people who hire lobbyists?

Yeah, well, contractors do.

Yeah, contractors, your Lockheed, your Bowings, I don't want to drop too many names.

But we're going to have to take another break, and I encourage everyone to check out the podcast on iTunes.

I encourage you to check out Facebook, your Twitter, your Google, your Pinterest, all the stuff the kids are into.

www.startalkradio.net We will talk to you on the other side of this break.

Welcome back to StarTalk Radio.

Bill Nye, the science guy here, guest hosting this week on our Cosmic Queries edition of StarTalk.

Here as always with Eugene Mirman and special guest this week, Mike Massimino, call him Mass.

He flew in space.

Now Mass, as we call you, you are following up on this question about how do we participate in space?

Because they asked financially or otherwise.

What are other ways they can help NASA?

Yeah, financially, I'm not a financial guy.

But otherwise, I would suggest for Daniel who asked the question, and maybe some of his friends too, if you're interested in the space program and want to contribute, there's ways to contribute with your own interests and your own energy and your own efforts.

If you have a passion for the space program, which I assume he does, because he's taking time to write us a question, and whether he's interested in science or math or if he's interested in literature or art or comedy, in your case, right?

You never know.

And you're interested in the space program, use your talents to promote the space program, to work on the space program.

Get a job in aerospace.

Become an engineer.

Invent something.

See what's going on.

Make a space shuttle or a weapon.

Hey, but there's a lot of resources out there where you can find out what's going on in different parts of the country, different parts of the world, and see what you can do to make it part of your life.

I think that's the best way for a young person.

I'm assuming maybe he's not a young person, but.

I don't know, he has a last name.

He doesn't have a last name, so he's probably of some age.

Get involved and do it.

I would say, take it.

He's over five years old and under.

He's over, if he can write, so he's ready to go.

Or something to say about getting involved.

Yeah.

Well, getting involved in space, at least if you live in the US it means influencing NASA, yes?

I'm surprised more people don't hire lobbyists to, like get together, hire a lobbyist to just generally pressure all Congress people to have more funding for NASA.

Well, we do at the Planetary Society.

You do, so give you guys money and then you'll hire all lobbyists.

We just need.

We have one, we have one.

Yeah, but what if you had five?

What if you had.

There you go.

Yeah, I'm really now like, let's do this.

So well, along that line, as you may know, I did a little video, an open letter to the president of the United States, encouraging him to ensure that we have funding for this niche.

It's a line item within a line item.

Let's say NASA is a line item.

Planetary science is a line item.

I just want them to fund it at a level high enough to keep the current missions flying.

You know, we have Cassini flying around Saturn.

Messenger went to Mercury.

We got Juno going to Jupiter.

It's crazy, we got two rovers on Mars.

And those programs, the Curiosity rover, all in, developed over 10 or you could call it 12 years, cost one and a half billion dollars.

That's like one cup of coffee per taxpayer for crying out.

And let me tell you something that concerns me.

Let's stop helping kids and let's start helping space.

Is it a good cup of coffee or is it moderate?

But let me say, it's one and a half billion dollars, it's on Mars and it's not even locked.

Anybody could just walk up to it, it's shocking.

So you would have a mission to steal the rover on Mars.

That's not a bad contest.

As somebody, you'd have to build a thing to go to land on Mars, quite an extraordinary undertaking.

Let me ask a question.

Crime doesn't pay, folks.

Unless you can get to Mars.

That's why it doesn't pay.

It's too expensive to get to Mars.

Right, it's not affordable.

Okay, Gavin Boucher asks, he's from Melbourne, Australia.

He asks, do you lament the lack of funding, not just for NASA, but for science education in general, from a distance, the other side of the world?

It appears that America's school science programs are not receiving the backing that they should and are under attack from other influences such as religious and political agendas.

If I were a king of the footies.

Yes, we would have more funding for science, but if I may, let's not call it channel, but speak on behalf of my beloved colleague, Neil deGrasse Tyson, who would normally be hosting Star Talk Radio, if we had a robust space program where investment was being made at a higher level than it is now, and we were going to someplace new and cool with people like Mass, flying out into space, someplace new and exciting.

You wouldn't need to run in circle screaming about science, technology, engineering and math, which we like to call STEM.

It would just happen.

It would be the real trickle down of science.

That is a real thing.

Well, not just science, but exploration.

Right, adventure.

Exactly, because there's two things that happen, Mass.

You've been up there, you've done it.

When you go exploring, two things, you're gonna make discoveries.

You're gonna find things you never found before.

The other thing you're going to have, Eugene, and adventure.

Adventure, oh yeah, of course you'll have adventure.

Did you guys, when you were in space, did you discover anything?

Were you like, oh, this is a thing nobody knows about shoes?

Actually, it depends how you look at it.

We were more or less the workers, the maintenance people for the Hubble Space Telescope.

So we didn't look through the telescope, we fixed it, but our smart people here on Earth, all the astronomers, for example, Adam Reese and a group of other astronomers won a Nobel Prize.

The theory of dark energy and dark matter came out of Hubble observations.

Out of what you fixed.

Out of what we fixed.

So we were more like the repair people, but the astounding discoveries that were made.

But didn't you fly up with a snake in a box just to see what would happen?

Oh, like our own fun stuff?

Did you go like, yeah, we're gonna fix the Hubble, and while we do this, here's some snakes and shoes and let's see how rabbits act when you throw them in space.

No, we had Swedish fish, candies and stuff.

Yeah, we did our own little experiments, but we played baseball in space.

You didn't publish them.

Did you walk in space and play baseball?

No.

I walked in space and I played baseball separately.

We played baseball inside the cabin.

But we did participate in some human subject tests, but the big science objectives for us were to get Hubble fixed.

To discover dark matter.

To discover some really cool stuff.

Oh, around the term dark matter, dark energy, everybody throws it around like it's just, everybody knows about it.

It's an extraordinary, but Mass is the guy that...

So we gotta take another break.

We encourage you all to enjoy your www.startalkradio.net.

Check us out on Pinterest and check us out right after.

Welcome back, Bill Nye, the Science Guy here, guest hosting StarTalk Radio this week, the Cosmic Queries edition, and where we answer your questions.

Eugene.

Yes.

You got another question.

I do, from Andrew Robles.

Here we go.

Scenario, you're in an elevator with a congressman who has a lot of say over where tax money gets spent.

You have one minute until the elevator arrives at its destination.

What examples of economic, technological, or any other returns would you use to convince him that space exploration is worth funding more?

Mass?

With a minute to go, I would say that it's gonna stimulate the economy with new technology, new developments in the science field, new discoveries in materials and medicines and so on.

It helps education because it inspires young people and it promotes international cooperation because we have our International Space Station and other science programs, and it gives us something for our future.

It's about exploration in our future.

Yes, by my reckoning, you did it in 56 seconds.

All right, now onto my floor, and I'm on my way.

But Bill, what would you say?

I'd say space exploration brings out the best in us.

It's inherently optimistic.

It stimulates the economy in the US at least $3.60 for every dollar that goes in, and we make discoveries that literally change the world.

Astronomy has changed the world.

We found that the Earth goes around the Sun, that changed everything.

We found the Sun's not unique.

The first people were maybe punished for it, but yes.

It sounds like it, yeah.

But it did change the world.

And now people throw around the expression, dark energy, dark matter, like it's a day at the office, but we all take it for granted that there is such a thing or such things, and these were not discovered even really 15 years ago.

Who knows what new physics, who knows what is over the next horizon?

And Congressman, if I may just speak as a guy born in the US and as a patriot, don't you want the US to continue to lead in this thing?

Isn't that what you want, Mr.

Congressman?

Yeah.

Ms.

Congressman.

All right, here's another question from Cameron Nuss.

He wants to know how long, if at all, before a manned mission to Titan, would this be a public or private sector venture?

Yeah.

That's a long old way out there.

Titans, that's a long old way.

How long would it take to get to Titan, first of all?

It depends on your rocket ship.

Yeah, but-

You'll say I'm using one I got at Target.

Long time, how long would that take?

Cassini took five years, right?

Yeah, that's a long time.

Five years.

And this is, we don't have the technology right now to stay away from all that radiation.

It's not clear how bad that is.

How much radiation?

Enough to kill you, which you probably don't want.

Even to kill a baby that maybe could adapt more?

Yeah, and so on.

You have a lot of shielding.

You try to make it better, but-

What if we sent babies that grew up and then, no.

No, that's not how evolution works.

You'd have to have a whole bunch of babies and see which one made it through.

They'd have no trouble wearing diapers.

Mass has been there.

Send a 12 year old, a bunch of 12 year olds that will grow up slowly during the mission.

But what we-

You're a genius.

You need to be talking to that congressman in the elevator.

Mass, how much trouble did you have with bone loss?

My trips were two weeks at a time, Bill, so it wasn't too bad.

We've got that licked, we think, but we've got it licked through lots of exercise.

How much do you lose?

You can lose a very significant amount.

If you did nothing in space, if you did not exercise, you would lose a lot.

How much do you exercise when you go there?

So right now, to counteract that, there is some medicine you can take, and that's again a benefit of the space program, because it also applies to osteoporosis to prevent bone loss.

But still, the way we've gotten around that, we don't have bone loss, it's not an issue anymore, but what we have to do to counteract it is two hours of exercise six days a week.

Oh, wow.

So that's a lot of time.

So that's significant, it's a lot of time.

Because you're on the payroll.

There's machines with resistance.

Yeah, so it's a good point because you can lift weights all you want and it ain't going to do you any good in space, right?

So what we have is we have resistive.

Wait a minute, that's crazy.

You're like Hercules, Bill.

Yeah.

But we have resistive exercise.

You just have a machine that tries to crush you.

That's right, more or less.

Basically like that scene in Star Wars.

That's sometimes the way it's described when it's on the Fritz, be careful of the thing.

But it works on springs and therabands like you might have seen in rehab medicine.

So it's resistive exercise plus it's also, a treadmill is generally a popular way to exercise.

So it's both cardio and it's also resistive exercise.

And it's resistive exercise that keeps your bones in good shape for turning to dust.

And to this questioner, it's a long way and who's paying for it?

It's a lot of fuel.

Yeah.

Do we have another question, Fearless Leader?

We do.

So Justin Foley asks, how do you see CubeSats and other small spacecraft affecting space exploration?

I think these things are great, Bill.

It's the coolest thing.

What's a CubeSat?

It's a CubeSat, it's a small experiment that can be flown by universities.

I think high school students have done them as well.

10 centimeters by 10 centimeters by 10 centimeters.

Oh wow.

It's fantastic.

Those are great opportunities for science community and for education.

They fit on a standard launcher ring.

They go off from a standard spring-loaded gizmo.

And I gotta point out the Planetary Society is gonna fly two solar sails.

Stick with us.

There are CubeSats that will be deployed in space to see if we can develop technology to fly.

To other planets without any fuel.

So.

We'll have to talk more about that when we get back.

Yes, we'll talk more about that on the other side of this break.

Please stay tuned to StarTalk Radio.

Welcome back to StarTalk Radio.

Bill Nye, the science guy here, guest hosting this week on the Cosmic Queries edition.

Now, Eugene, you had a query.

Yeah, I wanted to know more about CubeSats.

So you were like, yeah, the university's gonna have them.

What is it, how do you make it, how much do they cost?

They're 10 centimeters by 10 centimeters by 10 centimeters, very small, fit in a lunchbox.

And it's a standard that can be launched from a standard system on board, a standard rocket.

And so you can launch generally seven at a time.

Universities make these things.

You can buy the circuit boards and software online.

Can a person launch it or you need a rocket?

Well, these things still cost a million dollars.

They cost a lot of money.

But you get a grant.

I mean, it's a program you can apply for a grant to NASA.

And then?

And if your grant is accepted and you have funding to do it, then you build your project, fly it in space.

It's great, it's a great way to, it's a relatively inexpensive way to explore space.

To explore space.

To put it this way, if your grant's accepted.

Nice, all right, let's do a lightning round.

Here's us to the lightning round.

A few seconds per question.

Here's a question.

Dyer Mayo wants to know, would it be possible to host a music festival on a radio satellite for a quote hip promotional event?

Is there a way NASA could start a nationwide door-to-door survey to get people to sign a petition to raise the NASA budget?

That sounds like a two-part question.

And I think if you got a corporation involved, excited about your music, that corporation could easily fund such a satellite.

The big problem will be getting a license and say, it's all solvable problems.

Get out there and do it.

Yeah.

All right.

Chagra wants to know, do we really have to choose between Cassini and Curiosity?

I don't want to lose either.

We at the Planetary Society are petitioning the US government to not have to make that choice.

There should be enough funding for Planetary Science, a line item within the NASA budget, to fund both missions.

The Cassini's out there.

How much money we've invested in that time, effort and energy?

For crying out loud, we've got to keep them both flying.

Here we go.

Debbie Large wants to know, why isn't there more news coverage of science advancement?

When I was a kid, all networks had a science correspondent.

That's true.

What the hell?

Well, now there's a whole channel called the Science Channel.

Yeah, but why not?

Yeah, but that's for people who already like science or want to watch toilets get built and how it works at a factory.

What about major networks being like, this is the weather and this is today's science?

I guess it doesn't sell well enough or else they would have it.

Yeah, there's other sources for that information mostly online.

We recommend planetary.org.

I just did a fabulous thing with IFLS.

I won't spell that out.

Just go check it out because it's the news of science.

I think it could be.

I think it's a shame that it's not seen as a more interesting topic or made more entertaining.

The three of us will fix it.

That's what we're trying to do now, but I agree it should be more in the mainstream.

I think it could be.

I think so.

Jimmy Class Manson wants to know, since China is now sending robots to the moon, does the US have any plans of doing the same?

Not right now.

There are congressmen and senators who insist that the US go back to the moon in some fashion.

There are other people that insist that the moon is a big gravity well and know we should go beyond it.

To start with, Mass, do you have an opinion?

I think we should go with the Chinese if we could.

I think it would be nice to cooperate.

Yeah, it would be fun.

Fabulous.

All right, here we go.

Andrea Humrey wants to know, what are you most hopeful about when it comes to humanity's relationship with the earth?

I'm most hopeful that people will find ways to innovate and engineer the entire planet.

I think that's the future as the human population continues to increase and our scientific literacy increases worldwide through education.

I think more people are going to get to see the earth from space, particularly artists and so on that are hopefully going to have the opportunity to explain it better.

I think it increases your appreciation of how beautiful the planet is.

So that's my hope.

Right on.

All right, Daniel Sprouse wants to know, Bill, why don't you run for office?

Bill Nye, the science POTUS has a nice ring to it.

Oh, sure.

So Neil deGrasse Tyson and I are working on our cabinet on who we'd have.

Do you guys want to?

Courtchester.

Courtchester.

No, wait.

Why'd you take that?

That would be a more fun job.

All right, you be the Courtchester.

I'll be the engineering advisor.

Advisor.

We're a package team.

All right.

So Stephen Stafford wants to know, how do I get the people in my life to see the importance of space exploration?

I try my best to spread the word and show the wonders of our universe, but no one seems to care.

Also, I'm a very poor student and can't afford a membership to the Planetary Society.

Think you can help me out, Mr.

Nye?

I don't know why you're having trouble influencing people.

It sounds like you are a pretty convincing guy.

Stick with it.

All right.

Here we go.

Here's a question from Nick Clarity.

NASA is sending us back to the moon, quote, for good and also for preparation for Mars.

How much actual engineering on the moon will prepare us for Mars?

Can we really learn what we need for Mars from the moon or is it a waste of money?

I refer, of course, I harken to Tex Johnston, the test pilot on the very first 707 airplane who remarked, one test is worth a thousand expert opinions.

Let's go try it.

I think the moon is our playground and we can learn a tremendous amount on stopping on our way to Mars.

Yep.

How hard could it be?

And Europe.

This has been a fabulous Cosmic Queries edition of Star Talk Radio.

I want to thank my guests, Mike Massimino.

Mass.

Massimino.

Massimino.

Eugene, we have got a good example of why for my entire life I've been called Mass.

We're out of time.

You guys, we're out of time.

Eugene Mirman, spelled just like Mir, the Russian.

I am Peace Man slash World Man.

So join us next time on Star Talk Radio as we work together to do I say it.

Change the world.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron