About This Episode

Can a whole universe fit inside a black hole? On this episode, Neil deGrasse Tyson and comic co-host Paul Mecurio explore grand unification theory, black holes, the collapse of the wave function, and other problems in physics with theoretical physicist and author of Existential Physics: A Scientist’s Guide to Life’s Biggest Questions, Sabine Hossenfelder.

Should science yield elegant answers? We discuss the halt in progress in foundational physics and the science community’s obsession with symmetry. What do you do when your life’s work turns out to be wrong? We dive into patron questions like: what do we gain by taking more detailed measurements of the cosmic microwave background? Learn about the B-mode and dark matter research.

Does our consciousness collapse the wave function? Find out about the observer effect in quantum mechanics. Does quantum mechanics play a role in consciousness? Does time exist within a black hole? We explore whether wormholes are one-way, and who could possibly be inside of a black hole. What’s the difference between proper time and coordinate time?

Are there other universes inside black holes? Discover the shape of the multiverse and cosmological natural selection. Could it be that the most successful universes have the most black holes? When is it time to give up on an idea? What is dark matter? Is it a particle or is it modified gravity? What would be the best way for the universe to be destroyed? All that, plus, could the Big Bang be the result of another universe getting extruded through a black hole?

Thanks to our Patrons Frederick DesCamps, Devon, Sunny Irving, Michael Gessner, and jack50 for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can watch or listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

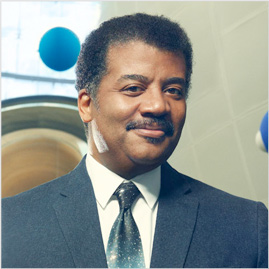

About the prints that flank Neil in this video:

“Black Swan” & “White Swan” limited edition serigraph prints by Coast Salish artist Jane Kwatleematt Marston. For more information about this artist and her work, visit Inuit Gallery of Vancouver.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTWelcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk Cosmic Queries edition.

As always, I’ve got a co-host who’s a stand-up comedian, Paul Mecurio.

Paul, welcome back to StarTalk.

Nice to see you again, Neil.

Great to be back.

And I can count you as my friend that we had a couple of lunches together, and so you’re more than just my co-host.

Yeah, you treat us to a great lunch, and the three of us need to do that again soon.

We were talking about that.

Yeah, excellent, excellent.

And so also, just some people, if they don’t otherwise know you, or they know you only a little bit, I first knew of your work as the warm-up guy for the audience for Colbert’s The Late Show.

Then I see clips of you do and stand up on the show.

Excuse me.

Yeah, I’m a big shot.

And one would call me an international superstar.

At least that one person would be me.

Yeah, or your mother.

Or my mother.

No, I left Wall Street to be a comedian, so I think the word she uses is disappointment.

But yeah, no, I mean, Stephen and I go back to The Daily Show together.

I was a writer-performer on that show.

And so, yes, I’ve been part of that DNA of those shows for a while.

But yeah, that’s where we got to know each other.

Excellent.

And you’re always great on the show.

Oh, thank you.

Thank you, just as a guest.

So today, we’re tackling the big questions.

The big questions.

And that could mean different things to different people, but on this show, it means the big questions in the universe.

And we combed the world.

No, we combed the universe.

And we found someone who just published a book titled Existential Physics, a scientist’s guide to the biggest questions.

And that person is in the house right now, except dialing in from Germany.

We have Sabine Hossenfelder.

Do I pronounce that right, Sabine?

That was wonderful.

Excellent.

Excellent.

You’re a theoretical physicist.

And Paul, it’s not that she’s theoretically a physicist.

I just want to clarify that.

She’s a theoretical physicist, a research fellow at the Frankfurt Institute of Advanced Studies, of course, in Germany.

And you’ve got a popular YouTube channel called Science Without the Gobbledygook.

How could you not tune into that with a name such as that?

And one of my favorite works of hers is an earlier book that was indicting the expectation that elegance and beauty and math should guide science.

And I agree, Sabine, with you 100%, that it has often derailed what could be an actual discovery because we lace our own expectations on what the universe should be.

Could you just comment on that briefly?

Yeah, it’s an ongoing disaster.

It’s still happening.

It’s not like it’s over.

Yeah, so my first book dealt with the question why there’s been pretty much no progress in the foundations of physics in the past 50 years or so since the standard model was completed.

So we’ve gotten stuck with all those big questions.

What is dark matter?

What is dark energy?

How did the universe begin?

And just to be clear, the standard model is the array of particles that we know exist in the universe and how they all fit together, how they interact and what forces they enact upon each other.

And that was quite an achievement coming out in the mid to late 20th century.

And you’re saying there hasn’t been much fundamental progress since then.

For what does theory development is concerned?

So, since the time that the standard model was completed in the mid 1970s or something, loosely speaking, there have been a lot of experimental discoveries.

A lot of the particles in the standard model had not been observed at the time, like, for example, the heavier quarks and stuff like this.

Of course, the Higgs, which wasn’t…

Higgs boson.

Exactly.

Right.

Which was only experimentally confirmed 10 years ago, right?

It just had the 10-year anniversary.

But for what the mathematical structure is concerned, it hasn’t changed.

And…

And Sabine, don’t feel alone about this.

We haven’t been back to the moon in 50 years, okay?

So you’re not the only one.

Is that because so much information came out of that first tranche of discovery that just sort of processing all of those different elements of knowledge just takes so much time that it’s hard to sort of advance to another tranche?

Is that one particular reason, maybe?

Well, the message that I’m trying to get across in the book is that the problem is the physicist got too enchanted by certain ideals of beauty.

So Paul, her answer is no to that question.

By the way, for the record…

I’ll translate.

For the record, Sabine, I was this close to writing that book.

You beat me to the punch by like an hour.

I had it almost all done.

Yours came out.

And I’m like, you know what?

Forget it.

I’m not going to bother.

What’s an example of one of the most distracting beauty elements that people want to be true in the universe?

Unification, I guess.

So after this standard model was completed, there were a lot of physicists who thought it should be more unified.

They were looking for this grand unified theory, which was pretty, you know, at the time, I think at the 70s, 80s, they thought it was pretty much around the corner.

And it’s out of this spirit that string theory was born.

And although what happened was that all the predictions that were made from those theories were falsified to the extent that they could be falsified.

So now we’re left with the non falsifiable ideas.

Yeah.

So it was grand unification, also symmetry, supersymmetry.

But this is a good tradition, though, Einstein was headed there, right?

So you don’t want to be in the wake of Einstein’s work?

Well, for one thing, I think Einstein wasn’t driven by symmetry, though it’s certainly true that the way that we understand general relativity today, it’s based on symmetries.

But I think it wasn’t it wasn’t Einstein’s intention.

But so what happened was that I think in the 70s, 80s, relying on symmetries was the next natural thing to do, it had worked before.

So of course you do it again.

But the the problem was it didn’t work.

And physicists just didn’t learn the lesson.

So instead of saying, okay, we tried it, it didn’t work, let’s move on and try something different.

They tried the same thing over and over and over again.

And basically, they’re still trying it.

So how’s it surprising that there’s no progress?

So, I bet you’re you’re popular at their parties.

You get a lot of them, my invitation must have been lost in the mail.

Exactly.

So, is it because they lack the security of their own analysis that they keep testing it over and over again?

I mean, is it I mean, you know, they’re not insane, right?

There must be some rationale in their mind that they they keep retesting the same.

So, maybe there’s doubt in their own mind about their processes or their analysis?

Yeah, I think there’s not one factor to it, but a couple of them, which is why my book has 300 pages.

So, if it was that short an answer, it wouldn’t have been worth writing a book.

So I think it’s partly a lack of understanding of the philosophy of science.

So, I think that they’re not really thinking about what’s going on, so they don’t recognize it’s not working and they try the same thing over and over again, even though good scientists, you know, should use the scientific method and not do this kind of thing.

But it’s also, I think it’s a community problem.

It’s kind of baked into the way that academic communities work and the way that they are funded.

It’s just really, really hard to get out of some kind of research direction after you’ve spent a significant time of your career on it and do something else.

There are very few physicists, and I know some of them, so they exist, who said, okay, so we’ve tried supersymmetry, it doesn’t work, I’ll stop it and do something else, because it makes your life very, very difficult if you do this, because all your funding goes out of the window and your whole track record has evaporated.

So, it’s like being a one trick pony, like Def Leppard, right, like it’s like sort of just the same song over and over and you kind of get locked into it, yeah, I see.

Yeah, so I wrote something for Physics World and I wrote advice for postdocs, don’t be a one trick pony, my British friend was like, this is such an American idiom.

So, what’s Def Leppard’s one trick pony?

No, it’s their songs, everything sounds the same.

Oh, everything sounds the same.

It’s over and over and over again, it’s the same thing, yeah.

So Sabine, so that early work, that early book really puts you in a good way and it positions you to take on a broader topic here, sort of existential questions and so, what prompted you to write this book?

Oh, my first book is like really depressing, I mean, I was basically going on for those 300 pages about why there’s no progress in the foundation of physics and trying to explain what everybody else is doing wrong, which, you know, doesn’t exactly make me look like a particularly nice person and it kind of, I felt that it was necessary to write the book because I thought someone’s got to say it, you know, there’s no reason why the LHC should be seeing new particles, all those stories that they’ve told about dark matter as well.

LHC, the Large Hadron Collider.

Exactly, that thing.

You know, there have been all those stories, it would see supersymmetric particles of dark matter, it would make black holes and all that kind of stuff.

And all those supposed predictions were based on arguments from beauty.

And in my book, I explained this.

But you know, it kind of makes me this person who is always complaining about what other people do.

And I’m kind of unhappy with the picture that I’ve painted of myself.

So, I was thinking, you know, I would try to remind myself why I studied physics in the first place, which is that I was really intrigued by how much you can learn about nature from pure mathematics, basically, you know, all those symmetries that we were just talking about, they’re like really, really powerful tools that have taught us so much about how the universe works.

And a lot of those stories haven’t really been told to the public, like when it comes to those big existential questions, and so I’ve collected them in my book.

Good.

So you saw a gap that you’re filling.

Excellent.

Excellent.

So we got questions, we solicited questions from our Patreon fan base, and these are supporters of the show, and they get their questions on.

So apparently you have to actually become a Patreon member in order to even get your question looked at, much less selected.

So that’s kind of cold, I think, but that’s how that works.

I didn’t set up that rule, just to let you know, our producers and other folks who pay the bills set up that rule.

Okay, so Paul, why don’t you start off?

You’ve got the questions, I haven’t seen them or heard them, and I don’t think Sabine has seen them, correct?

No, so there’s some really great questions this time around.

So we’re going to jump in with Quentin on microwaves.

Where’s Quentin from?

Do we know where these people are from?

From Switzerland.

Well, tell us where they’re from, why you leave that out?

I was about to say, hi, greetings from Switzerland, before you started yelling at me, dad.

Switzerland is where the LHC is.

So this person is like on top of the situation.

Yeah, I was reading his thing and it said, hi, guys, greetings from Switzerland.

You see the tension, Sabine?

This is how this goes.

What more knowledge is there to gain by making more and more detailed measurements of the cosmic microwave background?

Love the show.

I think the thing that everyone is looking after at the moment are the B-modes, right?

They want to measure the polarization of the CMB to try and figure out if there were gravitational waves in the early universe.

Are you saying that there’s nothing in there that can help you in your dark matter search?

In the CMB, well, me and my dark matter search, exactly what are you talking about?

Are we all looking for dark matter?

My personal satellite has just launched.

So, the CMB does put constraints on dark matter, it’s been doing this for some time, and every time the data gets better, then the parameters of lambda CDM shift around for a little bit and people adjust their models.

I don’t think the CMB is the best tool to learn something about dark matter because it just, you know, the overall dark matter fraction of the universe is one of those parameters.

But what you really want to know, like where the properties of the dark matter stuff, if it’s stuff, become important is more on the smaller scales, galaxies, galaxy clusters, when you have to take into account how the stuff actually clumps.

And there are some things that you can do in the CMB, loosely speaking, because those structures give rise to gravitational lenses, so it distorts the CMB, and there’s a fancy name for it, which escapes me at the moment, but this is how it goes with my brain.

And you can look for this.

So this is interesting, but it has fairly large error bars.

So I think that the stuff with the B modes is more exciting if you want to understand how the universe evolves.

So I have a slightly different outlook on that, Sabine, but we’re going to get to that right when we come back from our break.

We’re going to take our first break from Cosmic Queries and our special guest, dialing in from…

What town are you in right now, Sabine?

Heidelberg.

Heidelberg, Heidelberg, dialing in from Heidelberg.

I have great memories of Heidelberg.

Hossenfelder.

We’ll be right back and we’ll learn maybe what Paul did in Heidelberg when we come back to StarTalk.

You don’t want to know.

No.

Hey, I’m Roy Hill Percival, and I support StarTalk on Patreon.

Bringing the universe down to earth, this is StarTalk with Neil deGrasse Tyson.

We’re back, segment two, Cosmic Queries.

We’re talking about the big questions and the release of Sabine Hossenfelder’s book.

Sabine, give me the full title.

It’s like Existential…

Existential Physics, A Scientist’s Guide to Life’s Biggest Questions.

There you go, there you go.

And it’s just always good to have someone in arms reach with that kind of expertise, because you just never know what…

By the way, I have a book coming out, Peanut Butter.

Do you need jelly or don’t you?

Yeah, no, I’m with you on that.

I’m with Peanut Butter doesn’t need jelly.

I’m all good with the peanut butter.

It’s 400 pages.

Sorry, Sabine, it’s going to be competing with your book.

I hope yours works out.

That’s all I’m saying.

So before the break, Paul, we got this question from this person in Switzerland, wanting to know whatever more detailed measurements of the cosmic microwave background can do for us.

Here’s what I would say, Sabine, that if I’m at a distance and I see a home and I see a region around the home that’s all green, and I say, oh, that’s like a green carpet or something, okay?

But then I get closer or I look with higher resolution and I say, no, wait a minute, there are blades of grass there.

And then I’d say, okay, so it’s a green thing made of blades of grass.

And I look even closer, wait, the blades of grass have cells in them, right?

And so every next layer, I would not have even known to ask if that was there until I had that extra resolution that empowered me to inquire in ways I had not previously imagined.

So are you prepared to say that a higher, even higher resolution of the cosmic microwave background, there’s nothing there for us?

Like looking at a lawn of grass?

No, of course I would never say that.

You never know what you’re going to find.

It’s just my guess that we will have a bigger turnout from the B modes than from a higher resolution cosmic microwave background.

Can I ask like why is it that CMB gives us information about the nature of the universe just after the Big Bang, but not the last scattering?

And is there any movement on that?

Well, the phrase just after the Big Bang is kind of ambiguous, because all the interesting things that happen in the early universe are right after the Big Bang, like in the first like 10 to the minus 10 seconds or something like this.

So I’m afraid you have to be a little bit more specific.

So I guess the point is the cosmic microwave background is several hundred thousand years after the Big Bang.

Right, 380,000.

Of what had unfolded before then.

And so it gives us some insight into an earlier time, but maybe not as far back as you’re otherwise indicating.

As you’re otherwise indicating.

So what you say is of course entirely correct.

It’s kind of difficult to see through all this plasma, which is opaque.

There are several things that people have proposed.

I mean, looking for those gravitational waves in the B-modes kind of allows you to look back to earlier times, at least if you trust the interpretation.

People have also suggested to look for the neutrino cosmic microwave background, which should be there.

So they have traveled undisturbed for a longer time.

But the problem with the neutrinos is well, they interact very weakly.

So God knows how long it would take to measure this thing.

Maybe we’d be measuring, I don’t know, 100,000 years or something.

So don’t expect results anytime soon.

Neutrinos have always been very difficult.

They don’t play well with others.

No, they don’t.

At all.

So Paul, give me some more questions.

This is on wave function from Stephen Murphy.

I’m not sure where this person is from, but if I understand quantum physics correctly, there is something about measurements that collapses the wave function.

Some people, especially sci-fi authors, seem to believe our conscious observation of the measurement is what does the collapsing.

How do we know that our observation is not the key factor?

I think we know.

I think there’s an esteemed scientist, Dr.

Emmett Brown from Back to the Future, who said, if you travel in the past and you play with the past, you’re going to alter the future.

So I think we could just move on.

We could just move on.

Yes, exactly.

We don’t need Sabine to answer that.

No.

So Sabine, what do you have there, this collapse of the wave function?

Yeah, so I think this is something that people were really confused about in the early days of quantum mechanics.

Like when the thing came up, it became clear that there’s something going on in the measurement.

They didn’t know what, and they made what’s now known as the Heisenberg cut, which basically says wave function does one thing when you’re not looking at it, and when you do look at it, it collapses into something that corresponds to our classical reality.

I don’t think that today anybody believes this, or I mean, maybe I shouldn’t put it that strongly, but there are probably one or two weird people who still believe that consciousness has something to do with the collapse of the wave function.

But certainly the vast majority of businesses have abandoned this idea simply because we know that we can make quantum measurements without the involvement of any conscious observer.

We can do it with some kind of apparatus that was programmed by a computer.

In the future maybe we can do it with robots, or maybe this is already happening and I haven’t gotten the memo.

So what do you need consciousness for basically in the measurement?

Wait, Sabine, you just missed a deep discovery.

It’s that the machines making the measurement are conscious.

It’s obvious.

Oh, right.

So there’s evidence for panpsychism now.

It’s an AI problem.

How could you have missed that revelation there?

Come on.

Yeah, right.

So maybe more interestingly, it’s like the opposite combination that quantum mechanics plays some kind of role for consciousness has not completely gone out of the window.

Maybe most prominently, it’s represented by Roger Penrose, who thinks that something about those quantum processes and the measurement, the collapse of the wave function in particular, is necessary to give rise to consciousness in the human brain.

And I’m not at all convinced by this, but then he has won a Nobel Prize and I haven’t.

He won it for black holes, not for consciousness, just to be clear.

Yeah, so what does he know?

Yeah, what an idiot.

Everybody can have a Nobel.

I have one.

He’s one of the most eminent among us in the physics and astrophysics universe, Roger Penrose.

Still alive, still at it.

And I think he’s old enough so he can have some borderline flaky ideas and you still end up giving it some respect.

And so I think Sabine, that’s where you were landing there, I think.

Is that right?

By our chances, I just don’t understand it.

Time exists in black holes.

This is from Queensland.

Peter Jacobs, Australia.

Where it is a different time and a different day, in 293 degrees this winter morning.

This is what Peter says.

Alright, here’s this question.

Does time exist in a black hole and if you travel through a wormhole, could you end up in a different place and time and not be able to get back?

Well, I don’t know.

If you’re going to do air travel, by the way, Peter, right now, you’re not going anywhere because your place is going to be canceled.

You’re not traveling through any wormhole, anywhere, anytime.

Try taking a time.

Anytime soon, yes.

Anytime soon, exactly.

So Sabine, what happens, what’s the fate of someone, broadly, thinking about the fate of someone in a wormhole and in a black hole, other than that they’ll rip apart and die?

Hold aside that complication.

I’m still trying to digest the phrase a different place in time, but I think I know what it means.

Yeah, so the weird thing about Einstein’s theory is that he made time into a coordinate like space.

And it has the consequence that the labels on those coordinates are kind of a big use.

You can change them the same way that you can change the labels on your ruler from, I don’t know, inches to centimeters or something like this.

They don’t really mean anything.

So this coordinate time has to be enjoyed with a lot of care.

If you want to interpret it, usually what we deal with in Einstein’s theory is what’s called the proper time.

So this is the time that an observer would experience who would be traveling in this space time.

And for we know if you fall into a black hole or if you go through a wormhole, then your proper time just moves forward.

So you get older.

Where you come out in this coordinate time is a completely different question.

And indeed, if you go through a wormhole, you could in principle come out in the past according to this coordinate time.

And this is also why a lot of physicists believe that wormholes are hugely problematic because they could lead to all kinds of paradoxes.

You could go back in time and kill your grandfather, that kind of story.

And why does everyone always talk about killing their ancestors?

Why not just prevent them from meeting and then they don’t marry and have babies?

Why do I always got to kill them?

I mean, what’s, you know…

Or you go back and you ask that girl or that guy out that you wanted to ask out on a date and you didn’t, and then you ended up with the person you’re with and that’s not working out.

I’m getting too personal right now.

Yeah, I don’t hear your issues.

Because Sabine, my wife and I are not talking and I was wondering if you might be able to help.

Is there a quantum relativity therapy session that is needed?

Wait for my next book.

So in traveling through the wormhole, there really, the answer is you could end up anywhere at any time.

Is that sort of, for the lay person, is that sort of one of the answers there in a very crude way?

Mathematically, yes.

But no one’s ever built a wormhole and we have no idea how to build one.

Actually, most physicists think it’s not possible because it requires negative energy.

So who knows?

Mathematically, you can write it down.

I can get you negative energy.

Meet my mother.

Suck the energy right out of a room.

Why?

Why are you killing me?

You see, meeting your mother makes you travel to the past.

Exactly.

An important point that you just glossed over there, Sabine, that you go through into a black hole and you have what we call proper time.

But that’s as applies to you.

So it doesn’t really make sense to ask what is the time in a black hole?

Because it has to reference someone who’s making the measurement of a time.

And then you can get different measurements depending on whose coordinate is behaving in which way.

Is that a fair way to sort of add nuance to what you just said?

Yes, that’s of course entirely correct.

And it’s also why people get confused about this issue that it takes seemingly forever to cross the horizon of a black hole if you fall in.

That’s what you see from the outside.

So an observer who sits outside and sees you falling into a black hole would just see you freeze as you get close to the horizon.

But in your own proper time, if you fall in, it’s a finite amount of time.

And it’s a finite amount of time that it takes to hit the singularity.

If there is a singularity in a black hole, which we don’t really know, but assuming that there is one, it takes a finite amount of time.

So Paul, we can solve that question by you just visiting a black hole and see if there is a singularity there.

I am going to go.

I’m taking Amtrak just in case.

I was going to take Delta, but you know how they are.

They never get anywhere on time.

I’m sorry, Neil, real quick and follow up to what you just asked and Sabine confirmed.

You’re saying, again from a layman’s perspective, the person, the individual and the time and place at which that measurement is taking place specifically has an effect on the issue and the concept of time.

It’s not a general answer in terms of what we mean by time.

It’s specific to who and when.

I think classically you can think of this one time system everywhere.

And we learned in relativity that’s just not the case.

If time is just another coordinate, then you can experience that coordinate in different ways.

And so that’s how I think about it, Sabine.

Is that fair?

Yeah, I think that’s a pretty good summary.

Yeah, so you experience straight time falling into a black hole.

Someone watching you, it would take forever for them to see that happen.

And you both have perfectly legitimate wristwatches making these measurements.

And so what is the scientific measurement of a friend telling me a long-winded story that doesn’t do anything for me in my life?

The time…

They’re actually slowly falling into a black hole in them.

Thank you.

That’s exactly how I felt.

I couldn’t describe the feeling until now.

I’m falling into a black hole.

Which is why when I talk to people now, I want to wear a welding helmet up.

So if I find that the conversation is just going in a place that’s just doing nothing for me, I just put the helmet down and that pretty much tells you that we’re done.

That’s the evidence, okay, that you’re done.

That’s how I work.

Time for one more question.

Yeah, absolutely.

Other universes inside the black hole.

This is Ryan Gurntz’s.

And it says, Hey, everyone, I want to know how possible it is that inside black holes are actually other universes.

Yeah, we’ve all heard this Sabina.

And it’s kind of on the face of it, it’s completely outlandish.

How can this giant sucking machine called a black hole be the repository of an entire universe?

And Sabina, you’re going to answer that question when we come back from this break.

I want to know the answer too.

Very nice.

Damn it.

What the hell is going on inside of a black hole when StarTalk Cosmic Queries continues?

We’re back, StarTalk Cosmic Queries, Sabine Hossenfelder.

So she’s got a new book out on the big questions, existential questions in physics.

And we’re trying to get through some of these bigger questions about space, time, black holes and the like.

Sabine, how do we find you on social media?

Well, you can find me on Facebook under my name, Sabine Hossenfelder, or on Twitter under the handle SKDH.

Those are my initials, just in case you wonder.

And of course on YouTube.

And of course, your big YouTube channel.

And Paul, we find you on social media where?

Yes, at S-K-K-B, no, that’s yours.

I was wondering why I was getting all of these really intense questions about the quantum theory and you were probably getting ridiculous comments about comedy.

No, it’s at Paul Mecurio, M-E-C-U-R-A-O, all on Facebook.

M-E-C, Mecurio.

I had to drop the first R because of the Australian actor.

No, it’s because we have a planet with that and you don’t want to be confused for Mercury.

I think that’s really what it is.

That’s true, I get confused with planets very often.

Because Mercury’s got its own Twitter stream, just to let you know.

So Sabine, I remember the question from the second segment.

Are there, who’s the person who asked it, Paul?

This is Ryan Gurites.

So are there, we’ve heard, we’ve all read that you enter a black hole, there’s a whole universe opens up in front of you.

Could you like, have that make sense for any of us, please?

Yeah, so we don’t know what’s inside a black hole.

But it’s not just-

Okay, that’s the answer.

Paul, next.

Yeah, basically.

But that it could be-

Can I just say something?

Let’s move on to the next question.

Okay, but the theoretical hypotheses is what gives us this, right?

Yeah, so that it’s a black, that it’s a portal to another universe is one of the possibilities that people have put forward.

You can do it.

Basically, the reason it works is that, if you know one thing about Einstein’s theory of general relativity is that space and time becomes curved.

And you can curve it so much that you create pockets and those pockets can become infinitely large.

So black hole might be much larger in the inside than it looks from the outside.

And indeed it could be infinitely large.

So mathematically, you can stuff another universe inside a black hole.

It’s indeed possible.

And given that we don’t have any evidence that could tell us whether it’s true or not, I would say, yeah, it’s possible.

Here’s your Nobel Prize.

You just, I’m going to give it to you.

That’s the Russian doll theory.

Take it, run with it.

And you write up a paper.

But in a sense, isn’t that it?

Aren’t you saying that in a way?

That would mean black holes in that black hole universe would have universes.

Yes.

It would mean that in principle, Sabine, right?

Yeah, so that’s basically what Lis Molen’s idea of cosmological natural selection is based on.

So you have universes in black holes and those universes make their own black holes and so on and so forth.

So you get an entire tree of offspring of universes and then you have some natural selection stuff going on on them.

And I’ve forgotten the details, but this is basically…

In fact, he wrote a whole book on this idea.

He did write a whole book on it, yeah.

It’s called The Life of the Cosmos, I think.

So it would imply that the most successful universes are the ones that have the most black holes, because they would be making even more copies of themselves.

So you step back and say, what is the most common kind of universe?

It would be the kind of universe where the laws of physics promote the maximum number of black holes you can get.

And that would just be the natural…

That’s borrowed right off the pages of evolutionary biology, right?

That’s the idea, yeah.

Yeah, yeah.

Is this sort of related to this loop quantum gravity theory and sort of how…

He’s big on that, but I don’t know if they’re related.

What do you think, Sabine?

I don’t think so.

I think they’re pretty much independent.

I mean, pretty sure you can probably connect them somehow, but…

But I think he was also big on that idea as well, if memory serves.

I mean, since we’re talking about the universe, can you guys explain to me…

I love the beginning sentences like that.

Since we’re talking about the universe.

Well, how is it that Dwayne Johnson and Kevin Hart keep making buddy movies and the universe doesn’t implode?

How is that possible?

And either of you could address that for me.

Do you want me to move on to the next one?

We’ll get our top people working on that ball.

Just to be clear, Arnold Schwarzenegger made movies with Danny DeVito, okay?

You want to talk about odd couples.

He did.

That is true.

Tall and small.

Tall and small.

That’s the whole relationship.

And pretty good movies, actually.

Opinion or theory from your past?

That’s the title of this question.

This is from Adam Crow.

They’re not sure where this person is from.

Can each of you give an example of a cherished opinion or theory from your past?

Maybe that you defended publicly at the time, but now it turns out to be completely wrong as proven by new evidence.

I would like to hear some good examples of the scientific method as intended.

We don’t hold on to our beliefs in the same contradicting evidence.

So Sabine, what do you have going there?

Well, I wrote a whole book saying that there hasn’t been any progress in the foundational physics.

You know, I would have been happy if there had been something ruled out that I believed in, but I’m afraid I can’t really come up with anything.

What springs to my mind, though, is that I’ve changed my mind on dark matter.

So I have a background in particle physics, and for a long time I was pretty convinced it’s probably some kind of particle, because if you can use particle physics to explain it, why look any further?

Now I’ve pretty much drifted over to the modified gravity side.

Ooh, ooh, blood drawn, modified Newtonian gravity, this is like…

So we don’t need dark matter, we just have to fix Newton’s laws of gravity, because they’re incomplete.

So, ooh, ooh, she’s crossed over.

I’m just letting you know, Paul, she crossed over, she just admitted that.

Well, you know, I said modified gravity, you brought in Newton, so…

You know, I think we do need a relativistic theory.

A Newtonian non-relativistic one isn’t going to do.

Got it, got it.

I’ve been saying that for years.

So I have a more holistic view of that question.

I think it’s a great question, but I have a more holistic view.

It’s, I don’t run around espousing strongly things I believe in for which there is insufficient evidence to justify that confidence.

So I apportion the confidence I have in my statements according to how much evidence is available to it.

And I will follow the evidence wherever it takes me.

So it’s not like I have some cherished belief that then has to be thrown out the window and I’m kicking and screaming while it happens.

I’m there at every step of what the evidence is telling us.

And when you have conflicting evidence, then people choose sides, as is true here with dark matter.

And that’s a fun part.

That’s the bleeding edge of physics.

But the real problem comes about, and I think this is an important component of Sabine’s book, is that if you start holding tightly to a belief system that either has no evidence or only partial evidence, then you’re going to fall harder if the day comes where you’ve got to discard what might be decades of your invested hard work.

Where is that fine line?

If you apportion your confidence based on the evidence available, and I don’t mean you, I mean in the third person just generally, this kind of gets back to what Sabine was saying in her book about the lack of advances in 50 years, etc.

So, don’t you have to kind of walk the edge a little bit and say, okay, the evidence shows me this.

I have this level of confidence, 30%.

I’m going to make some assumptions and put myself out there and make this statement.

Not a problem.

The question is how much emotional energy have you put into it?

And Sabine, this is what you found.

People were totally into what they thought the universe should have been.

And will not give it up no matter what.

And that’s a problem.

Isn’t that right, Sabine?

Yeah, it’s psychologically really difficult, I think, if you spend a big portion of your life researching a particular idea that you’re fond of and then the evidence doesn’t come forward as readily as you thought it would.

And indeed, there’s conflicting evidence.

What are you going to do?

Are you going to admit that you wasted a lot of time of your life?

But, I mean, wow, you just described my life.

But wait, isn’t that a tautological argument on some level?

If you’re a great scientist or even an average one and you’ve spent the next number of years and it didn’t sort of play out the way you hoped or anticipated, isn’t that knowledge in and of itself that it’s not playing out the way you hoped and you did make advances because you disproved something that you thought was otherwise, but still you proved something?

You see what I’m saying?

Yeah, I see what you’re saying.

And yeah, that’s how it should be, but, you know, scientists are only human.

I guess the only thing that I have to add is that it gets easier if you do it more often.

I’ve worked on a lot of different things at this point, like in the past 20 years, like the phenomenology of particle physics and quantum gravity and modified gravity and a little bit statistical mechanics and some foundations of quantum mechanics and so on and so forth.

And you get used to giving up cherished ideas and just moving on and doing something else.

Yeah, so you like an idea, but maybe you shouldn’t cherish it.

Maybe that’s the problem.

So you got to temper your passion, I guess, right?

So Paul, we only have like three minutes left.

Yes, okay.

This is on vacuum decay from Sandra Pagliani.

I don’t know where she’s from.

What is most terrifying to you?

Vacuum decay sneaking up on us and suddenly destroying us or the big rip?

Which one is most probable to occur?

Also, given that we are matter, what are the chances that we bump into antimatter and vanish in a puff of gamma rays?

I don’t know why I had to go so dark.

Sorry about that.

Clearly Sandra is having trouble keeping a relationship.

Sandra needs to get help on that one.

She’s a little on the dark side.

She’s the Debbie Downer of this particular StarTalk session.

Yes, so big rip, vacuum decay.

And sound bites, what do you have?

I think the best way to die would be vacuum decay because we would all die without any advance warning and we would all die together instantly.

All right, that makes me feel good.

What?

And the thing about bumping into your anti-matter self, there’s hardly any anti-matter in the universe.

So if that’s one of your worries, put it lower on the list.

You know Sabine, what you just did with your answer, you just gave Tom Cruise the idea for his next movie where he saves the universe from vacuum decay by riding a rocket in an improbable amount of speed.

So I’m just putting that out there that you just created the next movie coming out.

Should we move on to another question?

Yeah, sure.

Angus McNeil.

If there are an infinite amount of planets in the universe, then does that mean that every possible planet from a video game or a made up world could exist with real life physics?

Now Angus is 12, so it sounds to me like he’s just trying to justify playing video games all day.

That’s what it sounds like.

And his parents are watching for the answer to see.

Ma, I got to play.

Neil Tyson and Sabine said that this is how it’s…

So Sabine, do you think he’s really thinking of the multiverse there instead of just the infinite number of planets in our own universe?

Yeah, it sounds a little bit like a multiverse idea.

So on some level the answer might be yes, there could be planets with other laws of nature.

On the other hand, I’m not sure that the kind of physics that you get shown in video games is actually consistent with the existence of planets in the first place.

So you have to be a little bit careful that if you actually work out the math, the universe still exists.

Well, it still exists, but in any…

I guess in any universe you’re in though, Grand Theft Auto is still illegal, like no matter what happens where you are.

But I’ve seen Mario, American jump off a ledge and then just scurry back onto the ledge.

There’s some really weird laws of physics in this stuff.

He never twists an ankle, he never blows out his knee.

It’s just, how is that?

How do you steal a car in three seconds?

But an important point, Sabine, I think if you imply this, if you didn’t say this explicitly, other universes might have slightly different laws of physics in them.

And so you’d have to create a system of laws that would be compatible with having planets.

We know our laws are compatible with planets because we’re on one.

And other evidence as well.

Paul, one last question.

See if we can squeeze it in.

This is Sam.

Good day.

I’m a tractor operator from Australia, so I listen to StarTalk a lot, and I got to thinking about black holes and the Big Bang.

And if no one actually knows how the Big Bang started, is it a possibility that the Big Bang was the result of a universe that had been consumed by a black hole and popped out of the back side of the black hole?

Whoa.

I say no because there’s flex tape.

And when you have flex tape, ain’t nothing popping out of the back.

You keep it together, you keep it together.

I saw that TV commercial.

I really want to try the part where you go into a pool and you put it…

Anyway, go ahead.

So let me reshape that question.

If the black hole can contain a universe, is that the same thing as popping a universe out the other side and birthing one?

Is that a fair way to think about that or not?

Yeah, and the answer is pretty much the same.

It’s possible.

At least mathematically you can do it.

You can have the universe come out of a black hole and glue this in the place where you normally have the Big Bang.

It’s one of the theories for the beginning of the universe that physicists have looked at.

Whoa, so my boy on a tractor in Australia is deducing the nature of the universe and he’s on a roll.

It tells you a lot about the current state of physics.

Or tells you a lot about how deep a thinker we got there on the tractor.

I just want to say, Sam, you just won the Nobel Prize, so congratulations.

Get off that tractor and come on down.

Come on down.

Maybe wear your tuxedo overalls for the ceremony.

How about that?

All right, we got to end it there.

Paul, always good to have you, man.

It’s great to be on.

All right, and Sabine Hossenfelder, it was a delight to have you.

Good luck with the book.

Sometimes it needs a little luck as well.

But the topics are, as you can see, deeply of deep interest to so many people, especially in our fan base.

So thanks for agreeing to come on to StarTalk.

Wonderful to talk to you, guys.

All right.

I’m Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

As always, I bid you to keep looking up.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron