About This Episode

Exoplanets? Low Mass Stars? Goldilocks zones? On this episode, Neil deGrasse Tyson and comic co-host Negin Farsad explore the universe of exoplanets, science communication, and acting with astronomer and speaker Dr. Aomawa Shields. Should Neil get an MFA in acting?

We discuss Aomawa’s Rising Stargirls program and how she applies her theater background to science communication. How do you connect people to the universe from an early age? Find out why Neil names lobsters before cooking them. We explore what forces lead Aomawa to acting away from astronomy and what phenomena lead her back. Is there ever too much school?

We ask some patron questions: How does having an MFA in acting help Aomawa communicate? Does it help get her funding? Are there any drawbacks? Discover Neil’s role in the cinematic arts and what he’s learned during his small forays into acting. Is it possible to terraform with current technology? Should we terraform if given the option? We break down the conditions where it may be morally acceptable to terraform a planet. Would it be better to just fix earth and explore for the sake of exploring?

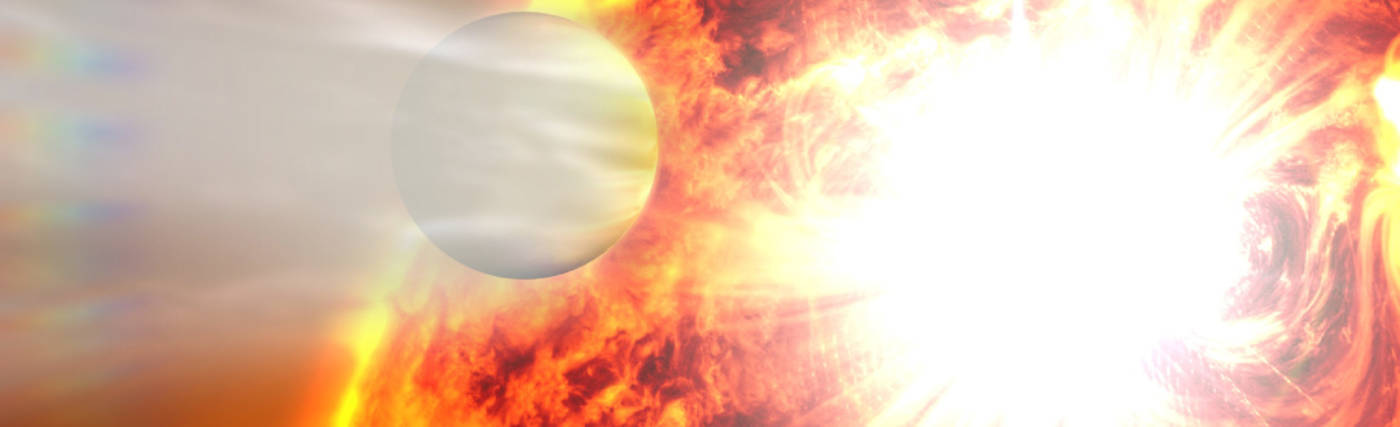

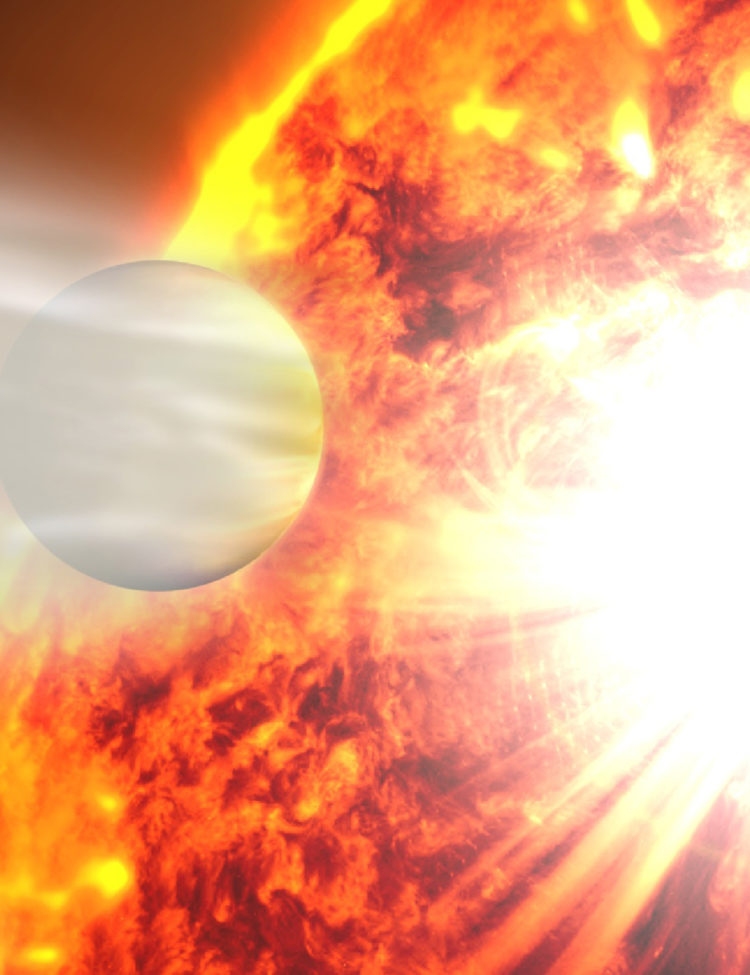

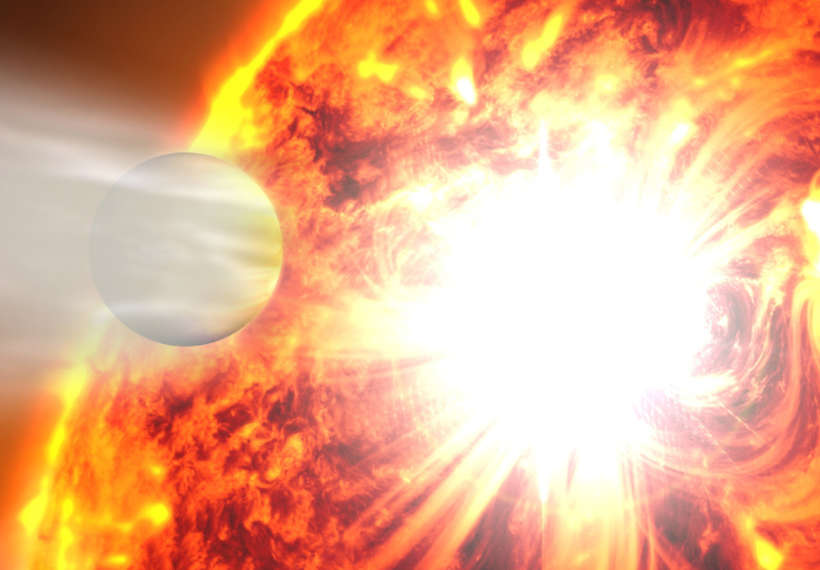

Could young red dwarf stars create a volatile goldilocks zone for otherwise habitable planets? What are the upsides of being a planet orbiting a low mass star? If you had to choose another planet to go to, where would you go? You’ll learn about fascinating planets in far off systems and what we know about them. We take a look at non-carbon-based life and whether we are biased in our search for other life in the universe. What about life that depends on wine instead of water? You’ll also find out the shape of black holes. Are they just a big landfill in the sky? Are we going to be able to travel to other planets if the universe is expanding so fast? All that, plus, learn about TESS– Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite– and other projects to discover distant worlds!

Thanks to our Patrons Jacob D. Fisher, Siosiua Hufanga, Thomas Cochran, Jasmine, Louis Cirigliano, Savanah Bisson, Jason Mahoney, Connor Snitker, Heffron, Lizzie B, and Mark Rodgers for supporting us this week.

NOTE: StarTalk+ Patrons can watch or listen to this entire episode commercial-free.

About the prints that flank Neil in this video:

“Black Swan” & “White Swan” limited edition serigraph prints by Coast Salish artist Jane Kwatleematt Marston. For more information about this artist and her work, visit Inuit Gallery of Vancouver.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTWelcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk.

I’m Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, and today we’re going to do Cosmic Queries with my co-host, Negin Farsad.

Negin, welcome back to StarTalk.

Oh, my God.

Hello.

Thank you so much for having me, Neil.

Hello.

So, you’re getting around.

First, you had this book.

How to Make White People Laugh.

What was the name of that book?

Correct.

It’s called How to Make White People Laugh.

I remembered it.

That’s because you technically are not a white person.

You’re something else.

Yes.

I’m just like this bag of ethnic is what I like to call myself.

Bag of ethnicity.

Yeah.

Yeah.

So you were born where?

I’m one of these nice Iranian-American Muslims.

And talking about white people.

Looking at America and figuring it out.

No, don’t even try because we can’t even figure it out.

I don’t know.

And also, you’re a host of, wait, let me remember, Fake the Nation?

Oh my gosh.

Neil, your memory is so good right now.

Someone’s taking their vitamins.

It’s Fake the Nation, a political comedy podcast, which you have also been on.

I have been on it.

And it’s on SiriusXM, if memory serves.

We actually just moved over to Headgum, but we think very fondly of those serious days.

Yes.

Okay.

Very good.

And I enjoyed my time on that, and I just know that I haven’t gotten a second invitation.

You know, it’s a very exclusive club, Neil, and we’ll get to you when we get to you.

Today, we have, for Cosmic Queries, one of my colleagues.

And I love it when we have one of my colleagues, because whatever astronomy I know, we’re bringing them in because they know more of whatever it is we’re talking about.

So they’re boosters for anything I could possibly do in the show.

And this is Aomawa Shields.

And please help me pronounce your first name, Aomawa.

That’s it.

Aomawa.

I get it.

I get a B plus at least for that.

Aomawa.

It’s been a delight.

I haven’t seen you in almost 15 years.

Great to have you on the program.

And to learn that over that time, you’ve become an expert in the search for exoplanets and the possible signatures of life.

This is really hot stuff.

And anytime there’s any progress in that field, I am glued to the research papers just to figure out where you guys are coming from, where you are and where you’re going.

And we’ve got a Cosmic Queries focused on that.

So I think we’re all in on you there.

So just let me get a little bit of your background here.

You’re an associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at UC Irvine.

Irvine, very cool.

Beautiful campus there, by the way.

And you’re specializing in Earth-sized planets orbiting low-mass stars.

I think low-mass stars are very popular in the galaxy, right?

There are.

We’ve got more low-mass stars than any other kind of stars, so you’re hedging your bets there, right?

Wait, so if low-mass stars were on TikTok, would they be the viral sensation?

That’s 70%.

70% of all stars.

Now I understand.

That’s how they roll.

And we will add to that the fact that before she went on to get her PhD in astronomy, she got a master’s in fine arts, in acting.

Acting.

And so how do you combine acting and modern astrophysics?

You can use that theater background to help communicate science.

And this is what she’s been doing.

And you got a website here.

It’s called risingstargirls.org.

I love it.

It’s promoting sort of interest in science among girls of all colors and all stripes.

Girls have been sort of underrepresented over the decades, not only in astronomy, but all sciences.

And so this is wonderful and it’s great to have you here.

Thank you so much, Neil, for having me here.

It’s really an honor.

And I’m excited to hear the cosmic queries and to talk about my background.

Yeah.

And I’ll dip in to see how your background can inform or enhance what we know or what education steps you’ve taken over your career, because I’m very much interested in that.

I’m a big fan of the arts, capital A.

So, you know, painting, sculpting, performing, writing.

Notice he did not say comedy.

You need a really capital A for arts, if I were to include comedy.

So, Aomawa, how has your website worked?

How does it work mechanically?

Someone logs in and then they see material there.

Take me through an encounter that a girl might have with your website.

Yes, so the Rising Star Girls is a program that I put together.

It’s been about six years now since it was officially a thing.

I had started back in grad school doing outreach to middle school girls of color, and I would always have some kind of interactive component I would bring them to the Planetarium at the University of Washington where I was a Ph.D.

student, and I’d show them a Planetarium show, and then we might do some kind of a project together like making their own little planet spheres, star charts that they could take with them.

And sometimes I would do a theater game with them, and I found that they really enjoyed that, and I think part of that was they knew they couldn’t get it wrong.

Middle school is that age where girls start to get quiet.

They start to raise their hands less often.

That’s where you lose them, that’s right.

That middle school, oh my gosh.

Yeah, they become more focused on their appearance and less focused on how they think and feel about the world, and so that’s the crucial age.

That’s what the literature says, and then of course girls of color, they’re in jeopardy because on top of the age group issue, they’re also young women of color, and there’s just not any role models, there are not many in STEM for them.

And so I thought, you know, how can I put my theater background that I had together with the astronomy background and help these girls realize that there is so much more to them than meets the eye and that what they think and feel about the world and the universe is actually not just important, but critical to their involvement in learning about the universe.

We didn’t just want to pummel them with facts, they would have to regurgitate in class.

We actually wanted to help them to feel connected to the universe and to that star or that galaxy or that planet they were learning about in hopes that if they felt connected, for example, by writing a poem about that planet, or that star or drawing a picture about an exoplanet that could actually exist, making up a name for it, making decisions about whether it actually had life or not, that they could look up in the sky and say, that’s my star, that’s my galaxy, I wrote a poem about it, to take actual ownership of what they were learning in hopes that once they hopefully continue on in astronomy, that they would feel that connection and that connection would stay put once the heavy math came in.

So that’s been well known.

If you name something, it becomes a little more personal.

And I’m omnivorous, and so when I buy a lobster and I’m about to cook it, I try to name it first, just so that I feel a little more deeply for it when I plunge it head first into the boiling water.

This is exactly what I’m talking about.

This is actually the same thing.

It’s the same thing.

I was just thinking about that exact analogy.

NASA, of course, names all their rovers, and there’s a participatory dimension to that that I think goes very far in educational circles.

But wait a minute.

You thought of, I read a little on your bio, you thought of making acting a career.

But the forces of the universe.

I actually kind of, sort of did for a while.

Descended upon you.

Oh my gosh.

So what pulled you back?

Yeah, I mean, I always had a day job.

I had started a PhD program right out of undergrad.

And I sort of did that because that’s what you did.

And I didn’t really, it wasn’t really a conscious choice.

That PhD program was in astrophysics and I had started it, did one year.

But I was incredibly divided.

I, people would talk about what movie they’d gone to see or the Oscars that were coming up.

And I was, I would perk up then.

But like the problem sets and the, I was just, I wasn’t focused.

We’re feeling it, we’re feeling it.

Yeah, so, and I didn’t, I looked around and, you know, I did have an African American man who was my advisor.

So there, I wasn’t the only, the only person of color in the department, but I was the only student of color, the only woman of color.

And I didn’t see a lot of astronomers around who not only looked like I did, but sort of acted like I did.

Like I had this thing where I really liked wearing makeup.

I liked fashion magazines.

I liked to wear nice clothes.

I dressed pretty fashionably, and I didn’t really see that as much of a…

Yes, the opposite, really.

Just the opposite.

You didn’t really care about that?

I’m thinking it’s kind of the opposite.

So there were all of these things.

So Aomawa, what you did was you had a little checklist of all the things to make sure you didn’t belong.

Exactly.

And I was looking.

I was looking.

I’m picturing you.

I’m picturing like a Devil Wears Prada astrophysics edition.

Oh, yeah.

And it was always like I was building a case from the moment I got there.

And everything was like, yes, check, check, check.

These are the reasons why I shouldn’t be here.

And when the opportunity presented itself in the form of a stodgy, white, old male professor who said, consider other career options, I took him up on it.

And it wasn’t what that was.

So just to be clear, it’s not that you intentionally did these things to be different.

It’s that these were part of who you were.

And that identity did not have receptors in the environment where you were to get your PhD.

And so that mismatch then sent you to an off ramp.

Is that a fair way to characterize it?

I think that’s fairly accurate.

I mean, I can’t blame it all on the outside forces.

There was a lot going on internally that I take responsibility for.

I think if I had known really, really known the way I did 11 years later, what I wanted to do, there’s nothing that would have stopped me from doing it.

But I didn’t.

I didn’t know that then.

And I was very sort of on the edge of a precipice.

Anything could have anything could have tossed me over.

And so I ended up going in the other direction.

Okay, so you took this off-ramp, and now you’re a professional actor for a bit.

But first I had to go to school.

And let me guess, your parents love the idea of you going into acting.

Here’s the odd thing about it.

They’re both performers.

They’re both performers and have been there entire lives.

But the answer is still yes.

They were like, oh, God.

They didn’t want that life for me.

They were very excited about me having what they considered a much more dependable career as a scientist.

Although it’s certainly, as everyone who’s a scientist knows, it’s hard to get a job in science after you get your PhD.

Plus, if memory serves, you also got romantically involved with an actor.

I know.

So this is like double.

There was no going back.

I think they loved the idea of being able to say, even though they were performer, performer, having a daughter that could say he was an astrophysicist was pretty awesome.

They gave him street cred at the parties.

Yeah, very good.

I burst that bubble and was like, I’m going back into the family business, so to speak.

I think they were certainly fearful.

How is she going to make a living?

But they wanted me to be happy above all else, and so they supported that.

During that first year in that PhD program, I applied on the DL to MFA acting programs.

I had done that during senior year undergrad.

But on the DL is on the down-low.

On the down-low.

Excuse me, okay.

Just have to get the lingo.

So I had applied to acting grad schools, actually along with astrophysics grad schools during my last year at MIT in undergrad, but I hadn’t got, I went for the fences with those.

I applied to Yale, The Globe at UC San Diego, and NYU.

So famous acting places, yes.

Yes, and I hadn’t gotten into those, and I was like, but I did get into astrophysics grad school, so I went.

So the second time around, when I was like, I’m going to apply again, I sort of spread the net more widely and I rode these sort of secret buses to Chicago from Madison, Wisconsin.

On the DL.

On the DL.

And applied and got into the MFA program at UCLA and decided to defer from my PhD astrophysics program at Wisconsin Madison, and I moved out to LA and started acting school there.

Can I just say, it’s just, you also seem like, I mean, what it sounds like so far is that you’ve been to a crap ton of school.

I’m collecting degrees.

So now it’s like, there’s a PhD, there’s an MFA, and I think you do the terminal degree, so you don’t put the SCV out there.

Okay, but before we take a break, I just want to know, was it the North Star that called you back?

What cosmic force said, uh-uh, or was it, come back to us?

Was it the whisper of the wind through the trees in the moonless, cloudless night as the universe poured from the sky back into your veins?

It was smog.

Smog.

I handed you a poetic thing.

You could have said, yeah, that was it, and we could have moved on.

Being able, I’m driving through the streets of LA to audition after audition in these cold, fluorescent lit, fluorescently lit rooms, casting rooms, and having my day job at working for a cultural nonprofit.

And every once in a while, my eyes crane up through the windshield, and I try to see through the smog, through the clouds.

And sometimes I’m able to see a couple of stars, and sometimes nothing.

But when I was able to see a couple of stars, it sort of shot me back in my seat.

Like, oh, that was another life.

And then I pretend I hadn’t seen it and just get back to driving in gridlock and trying to get to my job and put my flyers for different cultural programs around the city.

But that kept happening.

And I thought, someone asked me, a friend asked me, like, did you miss astronomy?

Because you could probably get a better paying day job doing that than your little cultural arts nonprofit or your temp jobs.

I once pulled staples out of paper for a year and a half for a music publishing company that had to have all of their contracts scanned.

They had to have them all scanned, so they hired three temps to sit in a room and pull staples out of the contracts.

You can’t scan documents that are stapled together.

You just can’t.

That’s great.

You know, I just want to say, as still a comedian and actor, I still go to auditions, and sometimes I look up into the sky, and then I think to myself, like, I could really eat a burger right now.

That’s a different thing.

But I still like the fact that you had applied to premier acting schools, and they rejected you.

I guess I’ll have to go to astrophysics graduate school.

I just love that.

It reminds me, there’s a Gary Larson comic where Einstein was playing basketball, right?

And the caption is, Albert Einstein was going to be a star basketball player until an ankle injury turned him to physics, and then he became a physicist.

We got to take a quick break, but when we come back, more with Aomawa Shields and the story of her life, and we’re going to bring in some cosmic queries that tap her expertise on planets around other stars and the possibility of life on StarTalk.

I’m Joel Cherico, and I make pottery.

You can see my pottery on my website, cosmicmugs.com.

Cosmic Mugs, art that lets you taste the universe every day.

And I support StarTalk on Patreon.

This is Star Talk with Neil deGrasse Tyson.

We’re back, StarTalk Cosmic Queries.

I got my co-host, Negin Farsad.

Always good to have you here, Negin.

Oh, so happy to be here.

Yeah, and we have with us Aomawa Shields, a colleague of mine at University of California Irvine, and she specializes in planets orbiting stars in the search for life.

And to me, that’s the hottest topic in all of science, not just within astrophysics.

And Negin, you’ve collected cosmic queries for her.

Yeah, and I’m here to either just not say anything, or, because this is all for you.

But if there’s something I think I can contribute, I will, but probably not.

So let’s jump right in.

Well, actually, before we get into some of the more sciency questions, Jiraj Petrovic on Patreon just asked, he wants to know, he talked about Alan Alda dedicating a lot of time and money and effort into educating scientists about how to communicate with the general public, and asked of you, how has your acting training helped you communicate with your students and with the general public about your research and discoveries, and has it helped any way in getting funding for your research?

I love that question.

Thank you for asking it.

You know, when I first came back to grad school, so the second time around, I had, it had been 11 years between my PhD program in astrophysics, the first one, and the second one, which I started in the fall of 2009, and I had my MFA in acting by that time.

And you know, I had actually 70 years old, right?

I’ll give you my name, my dermatologist is Ben.

Yes.

I had a trifecta of issues that made for like fertile soil for the imposter syndrome to take root.

I had, I was an African American female in a field dominated by white men.

Just to be clear, the imposter syndrome is where you are actually qualified to do what you’re doing, but your confidence doesn’t measure up to that.

And you’re left uncomfortable in that setting.

Did I capture that right?

That’s right.

So I felt like at any moment, I was going to be found out for the fraud that I was.

You know, African American female, older returning students.

I was 34 years old the second time around, starting a PhD program with everyone else was straight out of undergrad, so they were like 22, 23.

And I was a classically trained actor.

And an astronomy PhD program.

And that last part is why that’s the connection to this question because I thought at first that I had to sort of sweep that like unseemly foray into the humanities under the rug.

People in the department were like, they thought it was really cool lunchtime talk, like, oh, you have this MFA in acting.

And I was like, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, but I’m here for astronomy.

My very first journal club talk, a journal club talk is when for grad students, usually you present someone else’s paper.

So a paper that someone else has written about some astronomical phenomenon in like a 20 minute talk.

You kind of do an overview of the paper or maybe show a few of the figures from the paper and then take questions.

And my first talk, the first one that I had to give, it was like, I went completely deer in the headlights.

It wasn’t the presentation part, that part I was fine with.

I was a classically trained actor.

I was used to getting up in front of people and talking.

But what I wasn’t used to was people talking back to me, asking me questions.

There’s this thing in the theater called the fourth wall, which is an invisible wall between all of us performing up here on stage and the audience.

And nobody breaks that fourth wall unless they’re invited, like in some kind of call and response.

So the fact that in a science talk, people can ask questions during a talk, after the talk, even before the talk, it was totally normal.

Wait, Negin, let me just clarify here.

What she’s saying is people are up in your face.

Yeah, so what I’m hearing is…

It’s not just sitting back, it’s like, wait a minute.

Is that…

What I’m hearing is that academia, right, academia, this is what it sounds like.

It sounds like a comedy club on a Saturday night at 10 p.m.

where you got a lot of drunk hecklers.

That’s what academia is sounding like to me right now.

Is that accurate?

Minus the alcohol, I think.

Were you essentially being heckled by astrophysicists?

That’s how I took it.

That’s how I took it.

I had no, I see, and this is like, I came so far over the course of that five years because now what I see a science talk is, it’s a conversation, it’s a discussion.

People ask you questions because they actually care and are interested and care about what you’ve presented.

In fact, not getting questions is worse than get been, it’s so much worse because that means people probably fell asleep or they just want to get to lunch.

So it’s actually a wonderful.

And Negin, if someone finds an error in her work, first of all, that’s good.

Second, you want it to happen there.

Yes.

With people who are actually your local colleagues, right?

And not out in the.

So I take it there isn’t a bouncer at the lecture halls that like ejects people who are asking too many questions.

There’s no one that will protect you.

And I certainly felt it felt like a verbal assault when I was new, when I wasn’t able to see the other side of it.

And so I remember talking to a professor later about it.

And he was like, you know, take a moment, take a breath when someone asks a question, take a breath, let it land.

And then if you have information, if you have something to contribute, say it.

If you don’t say, I don’t know, I can look that up and get back to you.

End of story.

Like it didn’t have to be the big deal that it was in my head.

And so now so many years after that, what I can say is this, my acting background absolutely does not only contribute, but it makes me such a much better scientist than I would have been without it.

Because not only can I communicate the significance of my research results, and I can do it in ways that people who are not scientists would understand without talking down to them, without assuming they know things that they may not have decided to learn yet.

I know how to do that because of the acting background.

And I also know how to network, because that’s all that acting is, is like you have to like introduce yourself at parties.

And like, I knew how to be a marketer.

And as a scientist, you actually are a business person.

You got to market yourself.

You got to get out and shake it, so to speak.

And to get that next job or that next, you know, that those connections.

So wait, Neil, are you inspired at all to get an MFA in acting, hearing all of this?

Well, so here’s what happened.

I’ve been asked on occasion to give like cameo appearances.

And like, I’m actually, I’m in six, is it six, five or six feature length films in very small cameo roles playing myself or someone very approximating myself.

And if you look at the early ones, I suck.

It was like, there’s this gap between my first couple of appearances and the next time.

Cause people said, we’re not invited in back at all.

So, but this sign of baptism rather than a formal training, I think I’ve gotten better at this over the years.

And I have to agree with Aomawa.

It is definitely infuses every aspect of how you interact with people and how you communicate, your facial expressions, your body language, your gestures, how you’re thinking about how the person is thinking about what you’re saying.

All that an actor has to think about when they’re performing.

And so yes, I have to agree.

But Aomawa has got the formal training where she can dig deep into that, far deeper than any place I ever have to go in my own profile.

But let me add something, because the question started off mentioning Alan Alda.

I don’t know how many people know, but Alan Alda used to host Scientific American Presents.

It might have been Science Channel or Discovery Channel.

And so he liked science and he’s always liked science.

And he would walk into a lab and be just like a regular person asking blunt questions.

And he noticed that scientists had a hard time figuring out how to communicate back with them.

And he said he wants to change that.

And so he co-founded an entire school at the State University of New York, Stony Brook on Long Island, where their whole purpose is to train professors and graduate students how to communicate the science that is their profession.

And, but Aomawa was like doing this from scratch.

And so you’re the OG.

And then.

Well, I love his center.

I’ve spoken with people at his center.

I love what they’re dedicated to.

It’s very close to my heart.

And it’s, you know, there’s a course that I teach now here at UC Irvine that’s communication skills for physicists and astronomers.

And it’s not just how to put a talk together, but how to deliver that talk to a broad range of audiences.

And the same thing, like Neil was saying, you have to, when you give a science talk, there’s an objective, just like an actor in a scene on stage or in a movie.

And it’s not just say the lines.

The objective might be to get the person to give me the money, to get all the way to the other side of the bridge.

Like you have, in acting school we learn, you have to have an objective with every scene.

It’s the same thing as a scientist.

What do I want to do in this talk?

Do I want to inspire?

Do I want to surprise?

Wait, Aomawa, are you saying it’s real when actors say, what’s my motivation?

That’s a real thing.

Method acting.

I didn’t want to believe that was a real thing, but you’re telling me that’s a real thing.

Meanwhile, you ask Aomawa, what’s your motivation at any point?

And she’s just going to say smog, you know?

See, that was what motivated the whole thing.

The motivation.

Let’s go to get another question.

Let’s get it.

Okay, so we have actually Zeke Majed, Brad Winter and Chase Kimes from Patreon all asked about terraforming.

And so basically the question is like, how possible is terraforming with our current technology?

Do we have enough public interest to actually pursue it?

I love it.

What do you think?

Go for it.

And tell us what terraforming is first.

Well, my understanding of terraforming is the principle behind it is that we would change or we would be dedicated to the action of trying to change a planet, an existing planet’s environment, atmosphere, ecosystem to be more amenable to life as we would want it.

So perhaps creating an environment in the most extreme case, which I, you know, out of a Mars or a Venus, you might want to create an earth.

And how would you go about doing that?

And so that you could create a planet where life could actually survive and thrive.

By the way, you began your answer there.

It sounds like this is not in the near future.

You began saying, it’s kind of, we think it could be like, maybe this is what we might think of doing.

It sounds like this is not around the corner.

The tentativeness that you picked up in my voice is more related to my, to be honest, moral stance on the concept of terraforming than any sort of scientific…

Well, are you all getting Star Trek on this?

Prime directors do not interfere with…

Well, it’s more of a, it is more of a should we than could we question for me.

And there are beyond Star Trek, there actually are other scientists, Lucian Walkowitz, who has an excellent TED talk about this, this whole question of, let’s not use Mars as a backup planet.

This idea of, yes, let’s go explore, let’s go explore so that we have environments as backup in case we screw up the earth too badly to be repaired.

And that is-

Is this like a dog peeing on all the trees that are out there?

Is this the same thing?

Well, I mean-

I feel like this is when I buy a pair of pants that are clearly two sizes too small, and I’m always like, I’ll get there, you know what I mean?

But I know I’m never really gonna get there.

I just wasted money on a pair of pants, you know?

It’s wishful thinking.

But what is the morality if-

Okay, wait, so let’s unpack this.

It’s one thing to say, why are you making Mars a backup planet?

Why don’t you just tend to Earth as we should?

So that’s one moral posture.

Another posture is these other planets, they might have life of their own, and we’re just taking over.

But if you confirm that they don’t have life of their own, what’s your problem?

You got a problem with that?

Hmm, interesting question.

Yeah, if the planet is sterile, then who cares if you pitch 10th there?

Yeah, I’d have to think more about that.

There is an entire planetary protection department at places like the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA’s JPL, that is devoted to that question of, we make sure that we don’t bring life with us to someplace where we’re looking for life and think, oh, we found life, but the life we found was the life we brought with us.

Yeah, yeah, somebody sneezed on the detector, right, right.

And also if we got there to make sure that our detection equipment is robust enough to be able to pick up on the life that we would imagine might be there.

But here’s the thing, how could we be sure that a planet absolutely, unequivocally was completely sterile and had no life or promise of life evolving on that planet such that we could then shape it and mold it however we want.

Oh, so you could just sterilize it yourself and then.

Yeah, that’s one way.

And you know, actually, I mean, I have people very close to me feel quite differently about this.

My husband and I have debates about this all the time.

I think he would take that stance of like, yeah, if there’s not life on there, why?

But the thing is, life as we know it might be very different from other life, life that doesn’t have water as its primary solvent.

Everything on earth, everything from the tiniest microbe to the largest elephant, everything requires water.

I saw a cool comic where two aliens crashed in the desert and they’re like crawling along the dunes and they’re saying, ammonia, ammonia.

Yeah, there could be some other kind of solvent that we would have no way of or had not even thought about, much less thought about enough to formulate a plan to create a detector that might be able to pick up on that in some way or a spectrometer or something.

So, I think it’ll be very difficult to-

Okay, so you’re no fun, you just want to fix Earth.

You know, that’s not fun at all.

I’d like to fix Earth and I’d like to explore for the sake of exploring, not for the sake of changing to fit our standards or what we think we would need.

Negin, we gotta take another break.

When we come back to our third segment, we might have to go into a lightning round so we can get more of those questions in.

You’re watching or listening to StarTalk Cosmic Queries and this is all about search for life on exoplanets when we return.

Hey, we’d like to give a Patreon shout out to the following Patreon patrons, Jacob Fisher, C-O-C-U-R-Hoof Ganga, and Thomas Cochran.

Guys, without you, we couldn’t do this show, so we are very grateful.

And anyone listening who would like their very own Patreon shout out, please go to patreon.com/startalkradio and support us.

StarTalk, Cosmic Prairies edition.

We’re talking about exoplanets and the possibility of them harboring life with one of the world’s expert on that very subject, and it’s Aomawa Shields.

Aomawa, welcome to StarTalk, and Negin, of course, my co-host, my guest co-host for this.

And you’ve got all the questions with you.

But before we go into that, Negin, how do people find you online?

Oh my gosh, you can find me at Negin Farsad, N-E-G-I-N-F-A-R-S-A-D, and…

And anything separating your first and last name?

No, just right through on Instagram, on TikTok, on Twitter, and oh, the fun you will have reading through my things.

Okay, we’ll be the judge of that, okay.

And Aomawa, other than your website where you’re encouraging girls to rise up to their fullest potential, how else might we find you on social media?

Yes, well, you can find my faculty website.

Just Google UCI and my name.

I can put in my first name only, Aomawa, and I should come up.

Yeah, that’s good.

That’ll find you anywhere in the world.

That’s right.

A-O-M-A-W-A.

That’s it.

Yeah, that’s all.

So you can just drop shields.

Who needs shields?

We have Prince, Madonna, Cher, Aomawa.

Negin, that’s how we’ll do it from now on.

And then my Twitter handle is also my first name only, Aomawa.

As it should be.

So Negin, let’s see how many of these we can knock out in this third and final segment.

And by the way, I think all these questions, we’re now only taking questions from Patreon, from our Patreon support.

So if you want to be able to ask a question, jump on in.

Join the Patreon.

Well, Michael Main, one of your members, asks, it is my understanding that volatile magnetic fields of red dwarf stars periodically cause large star solar flares which adversely affect planets within the star’s Goldilocks zone.

Is it possible for life to survive on these star blasted worlds?

I didn’t understand that question at all.

Because you’re studying low mass stars, which are cool and red.

And they’re very susceptible to flares and things.

So how do you get out of that one?

I think we back her into a corner, Negin.

So let’s see what happens.

I’m going to do my best.

Oh, I feel it.

This is a very popular question that I get at Science Talks, which I now welcome instead of fear, as we talked about before.

I love the questions.

And, yes, so the one thing about these low mass stars, these red cool M dwarf or red dwarf stars, they have a lot of advantages.

They’re 70% of all stars.

It’s easier to detect planets around these stars.

They live forever, like even forever, forever compared to regular stars.

But trillions of years.

Trillions.

So no red dwarf stars have ever died.

That’s how long their lifetimes are.

Their lifetimes are longer than the current age of the universe.

So no stars, no red dwarf stars have ever died.

But there’s…

So it seems to me you could evolve some badass creatures if you were around for that long, right, on a planet.

Yeah, so that’s the other…

Another advantage is that they would permit long time scales for both planetary and biological evolution.

But when they have these long lifetimes, that means that this like…

So all stars are really active when they’re young.

And think of this as like a terrible twos phase for those who have kids.

I have a daughter who’s three and a half, and like, yeah, her terrible twos phase is still going on.

Became terrible threes, yeah.

That’s right, but the terrible twos phase for red dwarf stars can last as long as a billion years.

Like that’s some terrible twos phase.

And during that time, the planets around these stars in this so-called Goldilocks zone, habitable zone, that region around a star where a planet could be not too hot or not too cold for water to stay liquid on the surface.

That’s what we call the Goldilocks zone.

Planets in that zone could be pelted by all of this high-energy radiation during this terrible twos phase.

And that could threaten the atmospheres of these planets.

It could threaten biology.

We know that, for example, UV radiation is harmful to biology, that’s why we wear sunscreen.

But think of it as like UV radiation on steroids for life on a planet orbiting a red dwarf star.

And that could be, but I’ll say that, so that could be bad, for sure.

And that’s certainly one of the largest disadvantages that people have brought up for life orbiting on planets.

I feel a butt coming, okay, sorry.

But if you’re, we know that there’s tons of life in the ocean, so you could still have life doing its thing and being nice and sheltered from UV radiation if it was at the bottom of the ocean or even just a couple of hundred meters below the surface.

And there’s that terrible two space, even though it lasts as long as a billion years, it doesn’t last forever.

And it could be that atmospheres are thick enough, for example, to withstand that radiation.

And we’ve done some studies to show that under certain circumstances, you might not, for example, deplete an entire ozone layer by that high energy radiation pelting the atmosphere, you could still have some leftover.

So it depends is the short answer to that question.

All right, so it’s not as bad as, so it is real that these are threats, but those threats don’t exhaust all possible ways you could survive them.

Correct.

Yeah, okay, all right.

All right, keep it going, Negin.

All right, Charles Maloof asks, if Earth was about to be destroyed and you had to board a ship bound for another planet where you would spend the rest of your life, which destination would you choose at the ticket counter?

And you should assume there’s already a habitable facility there and travel speed is a significant percentage of sea so you don’t age much from the journey.

They got this all figured out.

So, Aomawa, what is your favorite planet?

That’s really what that comes down to.

Yes, yes, it does.

I have a soft spot for a planet called Kepler-62F.

And I say that wistfully because this planet is 1,200 light years away.

And so it’s very unlikely that…

So you’re leaving the solar system for this destination.

Was that allowed, Negin, in this setup?

We’d have to, we’d have to.

We’re going to another…

Oh, I kept thinking exoplanets.

Yeah, because you have exoplanets on the brain.

But that’s okay, we’ll take it.

I’ll take it.

I guess it could be within our solar system.

Yeah, it’s still a good one.

Give me both answers.

So in the solar system, where would it be?

Well, Jupiter’s moon Europa is certainly a place that everyone is excited about.

And I’ve always loved because we’re fairly certain that there is an ocean there, except the ocean is below potentially kilometers thick ice.

So a very, very thick ice shell on top and then a globally salty ocean.

Aomawa, you’re thinking like a scientist, right?

You’re thinking you go there because that’d be cool to study it.

It sounds like he just said, where do you want to go to live?

Yeah, where are we hanging out?

Where are you gonna hang out?

Where are you brunching?

Like what, you know.

On another planet.

I always think about that on our planet.

It’s funny.

Ever since I had a child, it’s like I don’t want, I wouldn’t want to leave.

Like I wouldn’t want to leave to go to-

To bring your kids with you.

And then if you can survive them saying, are we there yet?

You know, then it’ll be fun.

Okay.

I’m going to choose Neptune because it’s my daughter’s favorite planet.

And she loves it because it’s blue.

And we haven’t talked about ammonia and how that does that and all that, but just because it’s blue.

And I think that’d be fun.

I would take any moon of Saturn because then you can look up and see Saturn.

That’s got to be beautiful.

So tell me more about Kepler-62L.

So Kepler-62F is this.

Oh, F.

Yes, it’s 1200 light years away.

It’s one of a five planet system orbiting this K star.

So a little bit cooler than the sun, not as cool as a red dwarf star.

And it’s one of the first planets that we were able to, my team was actually able to look at how the gravitational interactions between this planet and its siblings.

So this planet is not alone in its system.

It’s got four other siblings that are also revolting, going around Kepler 62, it’s parent star, how those interactions, how they can push and pull on each other and how that affects the climate of this planet.

And that’s what I study is how the climate of exoplanets is determined by a myriad of factors, including how planets push and pull on each other.

And so this was the first time.

Okay, so you’re biased because you studied the damn thing.

I did.

You take ownership, you’ve already planted the flag, the Aomawa Shields flag.

Yeah, and so I’d love to be able to go and see and test some of the theories and predictions we made on this planet.

All right, all right.

Again, thinking like a scientist, not just hanging out on the beach.

How much would you, I know, that’s all I’m thinking about.

How much would you age though going to that planet, to that exoplanet?

Well, I mean, we’re assuming, this question said a few percentage, few percent of the speed of light.

I mean, if we were somehow able to obtain light speed, it would still take us 1200 years to get there and 1200 years to get back.

So we’d be pretty-

Wait, wait, you wouldn’t age, but we’d all be long dead and everyone would have forgotten about you if you come back to Earth.

So just go and just don’t come back and you’re cool, you’re fine.

So Negin, keep them coming.

Here we go, Chaz Gencarelli says, when looking for other habitable planets, do we also look for signs of other life that’s not carbon-based?

I know silicon-based life has been talked about, but curious of the signs of other based life is easy to scope out.

I love this question because I’m always like, are you looking for carbon and then also like gummy bears and also like, what, I mean, what is the list of the things that you’re looking for, you know?

Yeah, and how biased are we in these criteria?

We’re very biased.

I mean, our N in scientific parlance, our N is one, meaning we have one example of a planet that we know is habitable, Earth, that’s it.

And so we’re using everything we know life needs on Earth as our metric for where else to look for life, what to look for on those planets.

And this is where the water bias comes in, right?

Because we all need water.

And you’re saying, well, we need water, so clearly everybody else needs water.

Yeah, and there’s three things, there’s three fundamental requirements that we’ve identified that life needs on Earth, and it’s liquid water, it’s an energy source, and in some cases, that’s the sun, and other cases, it might be just chemicals for life that’s underneath the bottom of the ocean and doesn’t have access to sunlight.

So stellar or chemical energy, and some sort of environment to form complex, organic molecules from elements essential to biology like sulfur and phosphorus and oxygen and nitrogen and carbon and hydrogen.

So that environment would have to be like the right temperature and the right pressure to sustain big molecules to experiment and make anything complex.

This is why water is the most critical of those three, because a terrestrial planet by nature has some kind of energy source and the basic building blocks in some form that are needed for life.

But what isn’t as common is liquid water.

And you can see that really in our own solar system.

And that’s what we know all life on earth needs is liquid water.

And so we use that as our criterion.

But as this question points out, it is limiting, because there might be other ways, and there are astrobiologists, and an astrobiologist is someone, it could be an astronomer, but it could also be an oceanographer, it could be a geologist, and an astrobiologist are very interdisciplinary.

They’re using their primary field of expertise to address questions related to life elsewhere, to answer the question of how are we alone?

What’s the origin, evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe?

So Negin, I want to find a planet that doesn’t depend on water, that it depends on wine.

That would be an interesting, grapes are a big industry there.

Wine is mostly water, of course, so I kid, I kid.

So Negin, we got to go, it’s serious lightning round now.

So Aomawa, you’ve got to answer questions in one word or one sentence at most, okay?

Let’s go, Negin, go.

Shayna Briscoe asks, is the event horizon of a black hole static or does it vary with an object’s ability to produce thrust away from the singularity, like singularity?

Basically, are they all wobbly or are they perfect spheres?

I’m a planet person, thanks.

So I can address parts of that.

If the black hole is rotating, the event horizon is not a sphere.

It takes on other shapes that in some cases resemble a donut.

So that’s all.

It’s the rotation that will alter the shape of the event horizon.

Otherwise, it’s just gonna be a perfect sphere around the singularity.

Okay.

Heidi Wagermans asks, are we able to get to other habitable planets if the universe expands so fast?

By the way, Heidi is from the Netherlands.

Yes, the universe is expanding.

However, we, especially because of recent times, we now have a new mission, a relatively new mission called the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite.

We call it TESS for short.

It’s the successor to NASA’s Kepler mission, which stared at one patch of sky for about 10 years and just kept taking pictures looking for planets that passed in front of their host star from our viewing angle.

And we actually looked, we saw little dips in the light of the star when the planet passed in front of those stars.

So TESS is actually an all sky survey and it’s looking at stars in the nearby solar neighborhood.

So because of that, we’re finding a lot more planets, first off around these cool, small red stars, because they’re the most abundant stars in the solar neighborhood anyway.

And those planets are much closer to us.

They’re going to be easier to follow up on, to look at with next generation telescopes and hopefully one day to try to journey to.

Okay, that wasn’t one word or one sentence.

I couldn’t figure out how else to do it.

Also, the expansion of the universe, our galaxy will hang tight for a while, even in the expanding universe.

So I think we’re okay.

And it’s great to hear that we’re discovering many more that are nearby, in case we’re going to make that escape list.

Round up the billionaires and we’ll escape.

Keep the beach destinations in mind when you’re putting together that list, you guys.

Okay, let’s get one more, one more.

We have from Ashley Cosdorf, a Floridian.

I’ve been wondering what a black hole does for the universe from a circle of life aspect.

Most things on earth are recycled.

However, black holes seem to only consume.

They’re not, yeah, black holes aren’t recycling.

What’s up with that?

Are they like the landfill of the sky or what?

Did I, is that accurate?

That is so funny.

I just watched, I was just watching Loki, the Marvel show Loki the other day.

And there’s this whole-

Yeah, Loki’s Thor’s brother.

Thor’s brother, yeah, the God of Mischief.

But he’s sort of taking a moral turn in this.

I won’t give it away.

But there’s this whole notion of like what comes after and this creature that, this void that kind of consumes all matter.

And I think the answer, I guess it’s my three-word answer would be I don’t know.

And I believe we don’t know.

Right, so the two I don’t knows that a scientist can utter.

One of them is they don’t know.

And the other I don’t know is no one knows because we don’t have the answer yet at all, no matter who you ask.

But I love how basically this is really judgmental towards black holes.

And I haven’t heard very many approaches to black holes that are like they just consume, consume, they don’t care about anybody else.

Well, I think, so here’s the issue.

Here’s how black holes win.

Selfish black holes.

Here’s how they win the day.

The reason why we recycle is because we don’t want what we just use to litter the environment.

That’s the only motivation to recycle, in addition to whether the material is renewable, right?

But that’s why, if it’s not renewable, you get to use it again and you don’t discard it on the shoreline.

A black hole eats it, you will never find it on anybody’s shore after that.

You won’t find it anywhere, it’s not in landfill.

You’re right, Negin, it is its own landfill.

But smells don’t come out, it’s not unsightly, it’s not in my backyard thing.

In fact, everyone should have a black hole in their backyard.

Well, and there’s a black hole at the center of every galaxy, right?

So maybe that’s it, Aomawa, here’s what we do.

So when we have galactic federations, that’s the garbage chute for all the trash that we collect in the galaxy.

I like it.

Can I also just say, we don’t know that if in black holes, there isn’t like a giant Etsy shop that’s selling repurposed from stars, cute handbags, okay?

Are you sure you wanted to throw this away?

Actually, some models for the interior of black holes have them open up an entire other space-time continuum.

So that, in fact, things that fall through intact could emerge on the other side, separate from our universe, entering a whole other universe created by the black hole itself.

And I’m surprised that there’s not as much science fiction that has exploited that understanding of black holes as I think should, but anyhow.

Guys, we gotta call it quits there.

Aomawa, you’ve been away too long, okay?

And delighted to have you.

This is a very popular topic and we have a lot of deep interest in this and maybe we can get you back on and continue it.

Or especially when TESS, what’s the status of TESS right now?

TESS is flying and they’ve actually found many potentially habitable planets now.

So maybe we can get sort of an update on TESS.

Yeah, because we didn’t specifically talk about TESS in this episode, but Transiting Explorer Survey Telescope.

Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite.

Exoplanet Survey Satellite, and I think we’d welcome just an update on what some of the findings are from that next generation of our search for exoplanets.

So Aomawa, thank you for being on StarTalk.

Thank you for having me, everybody.

All right, and Negin, always good to have you.

Oh my God, thanks so much for having me.

I learned something today.

Okay, that’s what this is about.

I learned that black holes are like real jerk-offs.

That’s what I learned.

But Negin, the way you said this, other times I did this, I didn’t learn a damn thing.

That was kind of, you copped the attitude there, admit it.

Well, Aomawa really used her skills on me.

I really, you know, I really felt like I got something.

So this has been StarTalk Cosmic Queries.

I’m Neil deGrasse Tyson, you’re a personal astrophysicist.

As always, I bid you.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron