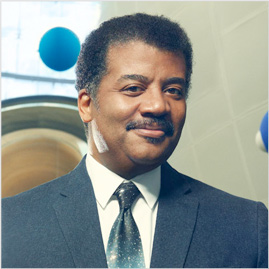

Get ready to explore the intersection of art and science, a subject about which astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has thought a great deal. He describes how art has enhanced his capacity to appreciate the beauty of the cosmos captured in photos taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. He explains how his favorite sculptures are inspired by celestial movements, and how he wishes science would show up more in books, movies and TV. (With shout-outs to The Big Bang Theory and Avatar). Neil and comic co-host Chuck Nice talk at length about The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh, discussing the difference between scientific accuracy and the emotions that great art inspires. You’ll learn about comets in Giotto’s Adoration of the Magi and The Bayeux Tapestry, the Music of the Spheres, the Golden Ratio, math’s influence on art, computer-generated art, Leonardo Da Vinci, M.C. Escher, chickens and eggs, artists and scientists, sacred geometry and so much more.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. This is StarTalk Radio. I'm your host, astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson. And we are here in studio in New York City. I...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

This is StarTalk Radio.

I'm your host, astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

And we are here in studio in New York City.

I got a co-host here, Chuck.

Sorry, you're not just a co-host.

Yeah, yeah, I appreciate that, Neil.

I kind of think of myself as your favorite co-host.

Keep telling yourself that.

So, what do we do on StarTalk?

I always have a comedic co-host, and we talk about the universe and all the ways that it impacts your life.

And with folks like Chuck in the room, you're probably gonna at least smile.

And if you're not rib split by the end, we're switching them out next time.

Yes, exactly.

If you haven't peed your pants, I'd get fired, basically, and I will commit Harry Carrey.

So, today we have one of our StarTalk After Hours sessions.

Yeah.

It's Cosmic Queries, and we're gonna spend this whole session just with you culling questions drawn from the internet.

That's correct.

All of our internet presence, which is wide and varied.

We got Twitter and Facebook and Google Plus.

So, the stuff is where it needs to be.

That's right.

And we found the ones related to the intersection, the collision, the blending of art and science.

Yes.

Two great tastes that taste great together.

They're like the Reese's Cup of the Universe, art and science.

You got science in my art.

You got art in my science.

I remember that stupid commercial.

So, I happen to like Reese's Cups, but I'm one of the last people not allergic to peanut butter, right?

Who's left?

It's so funny that it's true.

I never-

Back in our day-

I remember growing up, nobody was allergic to anything.

Anything.

Okay, now I have a son, he's allergic to peanuts.

And to the point, Neil, that I'm such an idiot that I didn't believe the doctors who told me that my son was allergic to peanuts because I forgot that there's another genetic code that he shares, not just my strong stock.

I mean, you didn't just birth him out of your rib like an amoeba, right?

Exactly.

But anyway-

Amoeba walks around and say, hey, I want another one of myself.

Right, so of course, you know what I did?

I took a little piece of, a little teeny bit of peanut butter.

You experimented on your son.

And I experimented, I was like, yeah, I bet you this kid isn't all that.

He's my kid, he's not a wimp.

Right, so I took a little peanut butter, I put it at the tip of my finger, I put it in his mouth and my son went into anaphylactic shock.

I'm not joking either.

I almost killed my son.

So that's the-

But it was for the sake of science.

It was for the sake of science.

Son, you did not die in vain.

So what do you got for me?

Oh man, let's get right into this.

Coming from Google+, this is Marcos D831.

Marcos D8, that's his code name, apparently.

That's his code name, you know.

So what do you think of computer-generated art?

Examples, genetic algorithm-based images, music, et cetera.

Yeah, I'm cool with it.

Yeah?

Really, really.

In fact, when it first came out, it was striking, because it was different and it had a different kind of sound.

But personally, I think that the computer doesn't yet know how to feel emotion.

And what is art without emotion?

That's my line.

May I say that cleanly, please?

I'm sorry.

What is art without emotion?

Okay, now you can butt in.

So, I mean, think about it.

You know, I love me some Escher, right?

The first MC, MC Escher.

MC Escher?

I don't even think I'm familiar with MC Escher.

You didn't hear him at the club the other night?

So the artist MC Escher, his drawings are like perfect illustrations of geometric forms, basically.

And so they're fun to look at, they're fun to get lost in.

But at the end of the day, you don't take emotional ownership of it.

Right.

And I think the greatest art allows you to walk up to it and say, that means something to me, regardless of what the artist thought or felt.

And then it's a communion between you and the creative energies of the artist.

If it's a computer just punching out notes, according to some algorithm, I don't know that it can reach those same heights.

But now with-

So maybe we need a computer that's like can cop an attitude.

That's what I was, yeah.

And then it composes music while it's under a disturbed mental states.

You need a computer that can have a broken heart.

That's right, you need a computer to get dumped by a girl.

A computer that, that means a computer's a guy.

Excuse me, don't you know that all computers that announce the end of the world are female?

Well, wouldn't they though?

Seriously.

There is two minutes left before self-destruction.

That's true, yeah.

It's not like, yo, get the hell out of there.

And see, that's why they don't make it a man's voice, because they would actually add some urgency to it.

You know what I mean?

Self-destruct in 10 seconds.

Right, yeah, the world will end.

What they should have is a brother, a real brother, just like, yo, man, you're gonna die.

Man, get the hell out of here.

What's your problem?

Are you crazy?

You still here?

That'll work.

That'll be the brother computer.

The brother computer.

Oh, damn, man, you dead.

So I think if a computer were to compose the blues, it would need to know sadness.

Right.

And I just don't know how that, maybe that they will come, you can program that in, but right now, no.

So yes, I'm happy to call it art, but it's not the highest levels of art that members of our own species have achieved.

So computers can make art, it's just art that sucks.

Exactly.

I'll accept that.

I'll accept that.

All right.

Okay, let's move on.

Oh, by the way, there's like startalkradio.net, and we tweet at StarTalk Radio.

And so with our website, our Facebook, just find us, we're StarTalk Radio, it'd be easy to find.

Absolutely.

Okay, what else you got?

Sounds good, man.

This is from Nathan Giardina, which is, what, if any influence-

That means Little Garden, I think.

Yeah, Giardina, so what, if any, influence did art have on your personal desire to be an astrophysicist?

What are your favorite current artists that explore science in their art?

So those are two-

Yeah, those are two questions.

I mean, we're short on time this segment, let me take the first one, which was-

What if any influence did art have on your personal desire to be an astrophysicist?

That, it had no effect on my desire to be an astrophysicist, but it enhances my capacity to appreciate all the splendor and beauty of the images that derive from it.

If you look at the portfolio of images from the Hubble Telescope, I mean, you feel it all the way, and I look at those images not solely as a scientist, but as one who is not an artist myself, but one who appreciates the art of the cosmos.

We'll come back in just a moment to StarTalk Radio, the theme, art and science.

Is it a collision or is it a blend?

See you in a moment.

Welcome back to StarTalk Radio.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and I'm your personal astrophysicist by night.

But by day, I serve as the director of the Hayden Planetarium here in New York City, which is a part of the American Museum of Natural History.

Known to some of you for its dinosaur bones, but we also present the universe.

And I got in the studio, Chuck Nice.

I'm your private dancer by night.

No, not, no, not, you're telling me that?

No.

So Chuck, so Chuck, you tweet.

Yes, I do.

Twitter dude.

Chuck Nice Comic.

Chuck Nice Comic.

Yeah, nice, nice, nice.

And I'd like the daily dose, you know, of just humorous observations of the natural world.

Yes.

That you provide.

Yes, sometimes humorous, sometimes disturbing.

Yes.

And I want you to bring some of that to this.

You're reading questions that we have culled from our various portals on the internet, the various StarTalk radio portals, and the theme is art and science.

That's right.

The merging, the cross-pollination, the collision.

What is it?

And I think a lot about this topic, and I was overjoyed when my producers told me that we were gonna spend some time on this.

And I haven't seen these questions in advance because they're your choices.

That's right.

That came out of the compilation.

And before the break, there was a two-part question, and what was the second part to that?

And remind me who asked it.

Nathan Giardina, who says-

Giardina.

Giardina, who says, what are your favorite current artists that explore science through their art?

Great question.

Now, I don't claim to be name-fluent among artists, but I can just tell you the kinds of art that I've enjoyed.

For example, the big public sculptures that appear in front of buildings, you know, many cities have a budget for that.

Those that tap the sky for their themes, I love them.

I love they want to invent a new kind of sundial or their sort of constellation patterns.

In New York City, for example, in front of the Time Life building on Sixth Avenue, across the street from...

Give me a second.

Time Life building, Sixth Avenue, across the street from 30 Rock.

From 30 Rock.

Oh, he's nice.

He knows his geography.

Yes, look at that.

His urban geography.

There's a huge sculpture in front of that building and it's a big triangle.

Yes, it is.

It's a triangle.

That's correct.

And people eat hamburgers under that and have no clue what it is.

It is a sun triangle.

Do you know that on the first day of the principal seasonal points of the calendar, at 12 noon, the sun aligns with each of those legs of the triangle?

I did not.

So, the more vertical leg of the triangle, on June 21st, first day of summer, 12 noon, sun time, it lines up with that leg.

On the shallowest leg, it lines up there on December 21st.

On the middle leg, it lines up both on March 21st and September 21st.

It is a sun tracking device.

And people just lose-

It's pretty brilliant.

I love it, I love it.

And forgive me for not remembering that fellow's name, but sculptors, that's their artist, of course, who are inspired by the universe.

I love them.

I love it when writers, that's a form of art, they think to cast a scientist as one of their characters instead of the cop, the lawyer, the doctor, whatever, because there's other themes they can draw upon.

Well, yeah.

I'm still waiting for the sitcom where there's a woman who's an entomologist who studies bugs, and she falls in love with an exterminator.

That's funny.

Okay?

So these are untapped themes, and I want science to show up in the everyday storytelling of novelists and poets, and all the people who are responsible for bringing culture and the joys and the pains of culture into our daily lives.

And do you know what the number one sitcom today is?

I just learned this.

I would guess, since you're asking, that it would be...

Taking too long.

I'm gonna go with Laverne and Shirley.

No.

In reruns.

Yeah, that's the number one.

No, of course it's the Big Bang Theory.

The Big Bang, yeah.

Of course, of course.

CBS is Big Bang.

Yeah, and so no, it's not high art, but it's art.

They're clever writers, clever, they've got a good science advisor, and it's a science advisor being brought in to the community of writers who are artists in their own right.

Right.

Helping to tell very fun stories about how, they're caricatures, of course, but they're fun caricatures about what it's like to just hang out with people who are scientifically fluent, scientifically literate.

And so I like the writers who do this.

I like the sculptors who do it.

I like the, anybody who has taken themes of the universe and blended it in with their art.

You know what I'm less impressed by?

Go ahead.

People who look at a Hubble photo and say, I'm gonna paint that.

Okay.

I don't need you to pack up the Hubble photo.

Right, I already have the photo.

I got the photo.

However-

Take me to a new place.

But would you not say that it's possible to take you to that new place by giving you an interpretation of what they see when they look at that photo?

Yeah, but the interpretations are just sort of color variance on what it is.

Here's what you do.

Take me to a Vista that's inside the cloud looking back out.

Take me to the surface of, take me to-

Okay, then I'll ask you this.

What do you think about James Cameron's Avatar, the movie?

Now there was a, he took us to a different world.

There you go.

And-

As they say in Texas, there you go.

You know, and so we had different vegetation, we had different animal life, we had different, you know.

He was completely informed by the vegetation on earth and by planets in orbit around stars.

And he had this background foundation of scientific information and he said, now I wanna take it to another place.

Literally and figuratively.

When you say he was informed by vegetation on earth, do you mean that he was smoking weed when he came up with that stuff?

Precisely.

No, because on earth we have plants and animals that have bioluminescence.

Well, he took that to an extreme.

That was cool, he thought about it.

He didn't just invent that out of the ether.

For everything he showed, there's some kind of physical, intellectual, artistic link back to what goes on here on earth, except for the unobtanium.

The stuff that made the clouds float.

He pulled that one out of where the sun don't shine.

But everything else, sure, and nine foot tall blue people, I'm okay with that.

That's kind of cool.

Except they had the USB ponytail.

That one, they just plug it in wherever they want.

Yes, yes, I know Captain Kirk would have done very well on that planet.

He gets his stuff wherever it is.

That's right.

He's got it.

All right, let's move on to a Facebook question.

That would be Captain Kirk of the original Star Trek, the original Star Trek television series for those who were born after 1969.

Oh, that's true, yeah, that's right.

I forget there's a lot of people who may not know about the original Star Trek.

Well, they know the later ones.

And the fact that the captain of the USS Enterprise was a poon hound.

Intergalactic.

Exactly.

All right.

All right, what else you got?

Here we go, Facebook.

And this is Heather Redding, wow, Mepholi, that's it.

Heather M.

Heather M.

Here you go, Heather.

What is your scientific reaction to Starry Night?

Love it or does it make your eyes burn?

Do you mean Starry Night as painted by Vinci Van Gogh?

Van Gogh, Starry Night.

That is the story.

The Starry Night painted in 1888 by Vincent Van Gogh.

And it is one of my favorite works of art of all time.

Really?

Yes, in fact, I have an oil reproduction of it in my office.

Nice.

It's actually the original, but don't tell anybody.

Right now there are a ton of people breaking into Neil's office right now.

Actually, if you look online on YouTube and type Cosmic Office, there's a tour of my office and it's in the background.

I don't actually point to it or mention it, but it's there.

It's there.

So I have it there.

I chose it as the cover of my second book.

That title of that book was Universe Down to Earth.

Got you.

And so, no, it does not make my eyes bleed.

It would if I were a scientific purist, not allowing anybody to interpret anything.

But in there, no, the moon is weird.

The moon doesn't look that sickle-shaped, no.

And stars are not like that vibrato, no.

And they're not that bright, no.

All right, I'm witty on that.

However, I will allow that to be how the sky made him feel.

Oh, so you're looking at this more as a representation of emotion.

Exactly.

Than an actual depiction of the sky or the cosmos.

I think it was, we only got a couple of seconds left here.

I think it was the first picture, work of art ever, to be named for that which was in the background, not the foreground.

The foreground, there's a Cypress bush, there's a village, there's a church steeple.

He didn't call it sleepy village.

He didn't call it Cypress tree.

He didn't call it church steeple.

He called it Starry Night.

The stuff in the backdrop that framed the village is the name and the subject of that painting.

There you go, background dancers.

Vincent van Gogh is your man.

We're coming back to Star Talk Radio.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

So this is StarTalk Radio, and we're back.

This is the Cosmic Queries part of our show.

I like to think of it as StarTalk after hours.

Chuck Nice, I got you in studio.

Thanks for being here.

Always a pleasure.

You're helping us go through some questions that is viewer mail, no, listener mail.

Listener mail.

It's all about the collision between art and science.

And we ran out of time in that last segment, but I was on a roll.

You were Starry Night-

Oh, man.

Obsessed there, man, in a good way.

But that brings up a question for me personally.

Okay, because I heard that Vincent van Gogh actually created more than one Starry Night.

Yes, he did.

And just before the break, I was describing the most famous of them, which is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City on West 53rd Street.

Correct.

By the way, just a couple of blocks from the Sun Triangle we described earlier in our conversation.

But yes, he actually has other paintings.

He has many paintings that were of the night or in twilight that showed moon crescents and stars and this sort of thing.

Another, he had two other Starry Night paintings.

One of them was at a cafe.

It's a cafe scene.

And you see it's a narrow, one of these narrow European streets and there's a little cafe and you look down the street and there's a sky that reveals itself flanked by the silhouette of buildings to its left and right.

And that is a kind of a funky looking version of, well, what it looks, it is a recognizable constellation.

That's my point.

And so that unlike the famous Starry Night where nothing matches anything, he has a real constellation there.

And there's another one where he's on the water's edge and you see a river, I forgot which river it is, but there you see in fact, the Big Dipper, not exactly a mapping of the real Big Dipper, but again, close representation of the Big Dipper.

So those are a little closer to a reality than the original one that's most famous.

And of course, who's the artist who composed the song Starry Night?

Starry, Starry Night.

What's the guy, McClain?

Yes.

I always confused him with a pitcher for the Detroit Tigers in 1967.

Dennis McClain.

I don't know Dennis McClain.

I get him mixed up.

Forgive me.

I'm not doing this from notes.

But anyhow, so he was compelled to compose an entire song based on artwork, based on the universe.

That's awesome.

And so talk about a collision, intersection, cross pollination.

You can't get more incestuous than that.

No, you can't.

I mean, serious.

I had no idea.

It's Don, Don McClain.

Thank you, Don McClain.

I had no idea that Starry Night was that far reaching in its influences.

That's pretty cool.

Yeah, yeah.

And I was on a tour of the Museum of Modern Art and they didn't know it was me because I'm an astro dude.

And it's, oh, here's one he painted and here's the location and here is the period.

Onto the next painting.

It's like, no, no, excuse me.

Get your ass back here in front of this painting because I got more.

Just, just, just let me tell you, let me school you on Starry Night when you just hate to be the tour guide that gets Neil deGrasse Tyson.

And this is Starry Night.

Let's move on.

You know, by the way, I'm an idiot.

All right, well, she got.

All right, here we go.

This is from Don Cancio.

And I would definitely like to hear Neil's thoughts on the golden ratio and the role of mathematics in aesthetics in general.

Thanks.

That's an awesome question.

Oh my gosh.

So it has been suggested since antiquity that certain proportions are pleasing to the eye.

No matter what your upbringing is, perhaps no matter even, no matter your upbringing within a culture and perhaps no matter even what culture you derive from.

And one of them is the golden ratio.

Yeah.

And I think it's one plus the square root of five over two.

So some, I'll look it up over the break, but I don't carry it in my head.

But what it does is it tells you how wide something should be for how tall it is.

And that's why certain paintings, certain pictures in their frame just feel a little awkward.

They don't feel pleasing and you can't even put your finger on it.

It's kind of an emotional force operating on you and a hidden intellectual force that's telling you, I like this picture better than that.

And you might not even know why.

I know why, because I'm looking at porn at that point.

For me personally, I'm just saying.

So you have other ratios that apply to porn.

There's the porn ratio.

We gotta check out that one.

Where my mind just went, go ahead.

So I like geometry.

Geometry in fact literally means earth measurement, geometry.

And it was applied to measuring distances and a long earth surface and earth is curved.

So you get some interesting mathematical discussions when you bring mathematics to bear on earth measurement.

But math I think is overvalued as a force in art.

Because in math there is no room for emotion.

True.

There just isn't.

And so the question is, is there something that's mathematically pure that is also emotionally rich or satisfying?

And by the way, people have been thinking about this since forever.

And it started with the music of the spheres.

They saw planets in orbit around the sun.

Well, there's a rhythm to that and the different orbits of different times.

Is there a ratio of those that means something mathematically that out of which you can make music?

And it was imagined that music, you can make awesome music from the universe.

And for all the music I've heard that came from the universe, it's not.

We gotta take a break.

We'll be back with StarTalk Cosmic Queries.

We're back on StarTalk Radio.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your resident astrophysicist, and I'm with Chuck Nice.

Yes.

Chuck Nice Comic.

That Chuck Nice Comic on Twitter, please.

Your Twitter handle.

That's my Twitter handle.

Get a handle on Chuck Nice Comic.

We left off with a question about the role of geometry and geometric shapes and forms as informing art, because you get geometry from math.

So that's math informing art.

And I think a lot of it is overrated in its role.

There's that golden ratio.

We looked it up over the break.

It is one plus square root of five over two.

So the ratio is one to that.

Right.

And the ratio of one to that, if you did the math, it's about one to 1.6.

So something would be of height one would be 1.6 wide.

Right.

And we're very pleasing.

And that becomes a soothing, pleasing visual effect.

Even though you're looking at a block of cement.

Exactly.

But it's elegant.

But it's elegant block of cement.

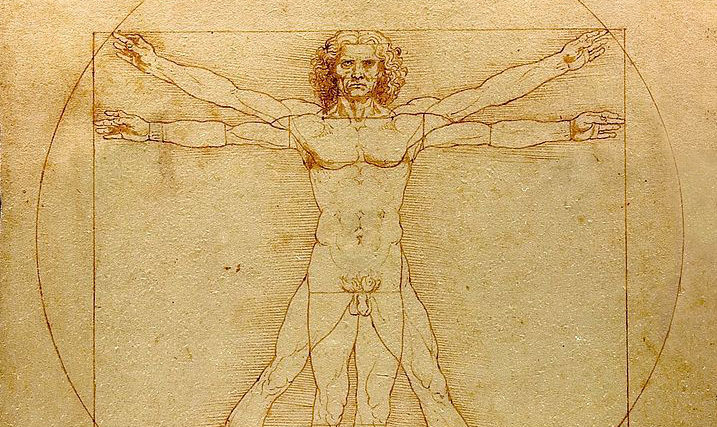

So now, what about my man Leonardo da Vinci and the Vitruvian man.

Oh, the dude inside the circle.

The dude inside the circle in his arms and, you know.

Yeah, yeah, that was really wishful thinking because once again, he was imagining that, by the way, there's sort of spiritual, religious implications here, that human being is a pinnacle of God's creation.

And if math is perfect and we are of God, then we ought to be perfect at some level as well.

If not our behavior, certainly our biological form.

And so he imagined that the perfect human would have these proportions and you put the guy inside the circle and the center of the circle would exactly line up with the belly button and the arms would then reach out and extend to the edges of the circle.

Now it's true for most people, the reach is approximately equal to your height.

But are you gonna say that that is most pleasing because that is not true for most people in the NBA and they're very highly paid people.

I happen to have very long arms compared with my height.

In fact, they're a foot longer than my height.

Really?

Yeah, which means I can punch you out.

So your wingspan is a foot longer than your height?

It's a foot, there's 84 inch wingspan.

And I'm-

You've been a great boxer.

So it's 10 inches long.

I'm 6'2 and my wingspan is 84 inches.

So it's 10 inches longer.

74 inches to 84 inches.

Yeah, or I could hold your head while you swing under my arm, never reaching me.

Yeah, the classic, yeah, just give that one up, go home right after that.

So I think, plus there were these metrics of beauty that people had presumed and established, the measures of Western beauty, what is the width of the cheekbone to the height of the face and the nose to the mouth.

Yes, you can measure anything.

And you can say that certain measurements repeat.

That doesn't make them important geometric forms.

It's just a geometric form that applies to that standard of beauty, right?

And so I'm not prepared to go and say, let's go look at geometric math to derive what is beautiful.

What people are doing is finding who everybody says is beautiful, measuring that.

Applying the geometry to that.

No, no, then they measure it and say, here are the beautiful numbers.

Right.

Okay, I'm fine with that.

But what I find interesting, it has been said that the most intriguing characters are not the ones who are most symmetric, but the ones that have a slight imperfection.

Yeah, like Meryl Streep.

Yeah, or Marilyn Monroe with the mole on one side.

With the mole on one side.

Yeah, and Harrison Ford, who was clearly the standout in the Star Wars series.

His face is not symmetric.

He has like a scar on one side of his face compared to the other.

I have a scar on one side of my face, but no one says that's beautiful though.

It applies to actors and not anybody else.

So you can measure this stuff, but in the end, I don't know that that's how I wanna decide who's beautiful.

I'd rather really just take a look.

Well, what do you think about the ratios when it comes to size and weight ratios?

Like for instance, certain it's been, I don't know if it's proven, but asserted that certain hip to waist ratios say fertility and causes a certain kind of desire in a man when he looks at a woman, breast to waist to butt ratio all that.

It's a family show.

Yeah.

Actually it's not.

But I mean, you know, so.

Did you say breast to butt ratio?

That's the first of those I've heard.

What can I say?

That's just me personally.

Okay, well we gotta check the journals on that one.

There may be no empirical medical evidence whatsoever about that one, but.

Okay, consider this, that any two numbers, any two measurements has a ratio.

Okay, that's true.

And although I look through time and I see the depictions of women in art, them ratios are all over the place, you know.

You're right.

Those Rubenesque women and then you go to the 1920s or the roaring 20s and flat chested women was the thing, the flappers.

You know, they were certainly not Rubenesque.

And so I'm not here to say that math is defining what we should be, but nothing will stop you from making those measurements in the first place.

Oh, I've already made my measurements.

We're gonna take a quick break.

And Chuck, when you come back, I want you to spend a minute.

Tell me about, you got some crazy show on-

On stage on Home and Garden Television.

I laugh every time I think about it.

You're listening to StarTalk Radio.

We'll be right back.

This is StarTalk.

We're in our last segment, Chuck.

This went fast.

Oh my gosh.

This just flew by.

Yeah, we're talking about the intersection, the blending, the cross-pollination, the collision of art and science, a subject about which I've thought quite a bit.

And you got the questions from the internet.

That's correct.

And keep them coming.

All right, so you know, we don't have a lot of time left.

Like you said, the show's kind of flown by, so why don't we enter our lightning round?

Oh, we don't, oh, there's a lot left, is what you're saying.

Because I haven't seen these.

You picked them, you found them.

Yes, so there's quite a few questions left, so we're gonna kind of breeze through them.

Okay, no, so this is the lightning round, and I will sound bite the answers, get through as many as we can.

As many as we can, okay.

Mm-hmm.

This is from Lee, on Facebook.

Lee asks, are we born scientists and become artists, or vice versa?

Which comes first, chicken or the egg?

Well, first of all, I have the answer to which came first, chicken or the egg.

It's the egg.

Laid by a bird that was not a chicken.

Whoa.

That is the answer to that question.

Daggone.

Got it.

Okay, second.

So you thought you was slick, slipping that in there.

Personally, I could be vice, but I think all kids are born scientists and learn to do and appreciate art.

Because what does a scientist do?

They turn over rocks and pluck petals off of roses and jump two feet into petals, and each of these is an experiment on the physical laws that operate around them.

They do that without being told.

But what happens when they get into the classroom, then they're said, well, here's the pasta and here's the glue, you're making a pasta collage, right?

So the art projects are kind of installed there, but you send them out into the yard when they're not running and chasing each other, they're actually exploring nature.

So my opinion, based on my observation of children and just the human species, is that we're actually born artists, but we're, I'm sorry, we're born scientists and then adults beat it out of them later.

And then we're taught how to then be creative.

Right.

So yeah.

All right, moving along, here we go.

I'm sorry, that was, I can do it faster than that.

That I dragged on there.

Do you think artistic ability could ever be learned or created through artificial intelligence?

So can a computer learn to be an artist, a true artist?

I think what it will have to do is be good enough to fool an expert, whether or not it has the right motive, the same motivation that an artist does.

So I think the answer is yes.

What are your thoughts on sacred geometry?

Is there any art or design, this is from Randy Huff, that does give healing property?

So there's the real caveat there.

If you see some form or geometry that heals you, that surely lives in the realm of the placebo.

It is an effect that we still don't understand, a medicinal effect where if you're given a pill that has no medical effects on you, but we tell you that it does, and you then get healed, there's some percentage of people get healed.

It is a not well understood phenomenon.

If it is your God who you appeal to, or your belief in the power of the doctor, or whatever it is, and it works, it's the placebo.

Gotcha.

There you go, what else?

So, I just, I before-

I love to say that, placebo.

Placebo.

Those are the cool words, and that is like polka dot.

And, all right, go on.

All right, here we go.

This is from Barney Atkinson, and I just have to get to this question.

If art influences science, how come the International Space Station is so ugly?

Ha ha ha, it's because art does not influence science.

Art influences design of architecture and hardware, but it does not influence science.

So those were engineers that had an opportunity to make the baddest looking thing there ever was, orbiting the earth, and out came something that looked like some, you know, an erector set.

And so, yeah, I'm a little disappointed now that you mention it, but we want to bring in some art and designers for when we go to Mars, because I want that to be the bad-ass looking thing that's ever come off the earth.

Gotcha.

Next.

Here's a great question.

Was there ever, this is from Cesar Avilla, was there ever a painting or sculpture during the Renaissance, or any other historical time, that captured an accurate depiction of the cosmos at that time?

Yes, there is Giotto's painting of the birth of Jesus, a very famous painting, in which he puts a comet.

Oh, we don't put comets to signify good things.

The whole history of civilization, where people have looked up and seen a comet, if you look at how they reacted, they said, oh, something bad is about to happen.

And so he took a leap and said, well, the birth of Jesus is a good thing to Christians, and a comet is just something in the sky.

And that comet is likely Haley's comet that he had seen in the sky at the time that he painted it.

Because if you date back the appearance of Haley's comet every 76 years, it lines up with when he made that painting.

So that is real science in a real painting.

Not only that, 1066, the Bayou Tapestry.

There is a dude pointing up at a comet.

The comet came in 1066 and it coincided with William the Conqueror.

Look at that.

There you go.

That's all we got.

That's all the time we've got.

Chuck, thanks for being on StarTalk Radio.

It's a pleasure.

And we find you on HGTV, busting into people's homes talking about him.

Home Strange Home.

I show up to white people's homes unannounced and they say, come on in.

Then you know the world has changed.

That's happened.

StarTalk Radio is brought to you in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

I'm your host and personal astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

As always, I bid you to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron