About This Episode

Geometry, physics and the other sciences describe the world we live in, and artists often play with these properties in their own imaginative investigations. From the drawings of Leonardo Da Vinci to high tech computer graphics, Neil and Lynne paint a picture of how science has inspired art through the ages.

NOTE: All-Access subscribers can listen to this entire episode commercial-free here: A Universe of Inspiration.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRTOur universe is filled with secrets and mysteries, leaving us with many questions to be answered. Now, more than ever, we find ourselves searching for those answers as the very fabric of space, science, and society are converging. As we...

Our universe is filled with secrets and mysteries, leaving us with many questions to be answered.

Now, more than ever, we find ourselves searching for those answers as the very fabric of space, science, and society are converging.

As we give you the knowledge that breaks the barrier between what is science and what is merely pop culture, this is StarTalk.

Now, here's your hosts, astrophysicist Dr.

Neil deGrasse Tyson and comedian Lynne Coplet's StarTalk.

Welcome back to StarTalk.

I am your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, joining me, my co-host, Lynne Coplet.

Lynne, you've been gone for two weeks.

I know.

Did you miss me?

Yes, I did.

I hope you were making people laugh wherever you were.

I was in Schomburg, Illinois, and I did make people laugh.

I had a lot of fun there.

Thank you.

Excellent.

Well, welcome back to the show.

You're my co-host.

Don't go away again.

I missed you too.

You know, today we're going to talk about the universe as it inspires the creativity of artists, artists throughout time and artists of all kinds, not only painters but sculptors and the like.

That's very interesting.

I've liked it because I've, you know, scientists, we hang out together and sometimes we're not appreciated as much as we would like to be for whatever reasons.

And occasionally we see some of our handiwork reflected in the creativity of artists themselves.

And we say to ourselves, maybe we're becoming mainstream.

Maybe we're creative and we're not nerds.

No, well, no, we...

Let's take credit for that.

Okay, I'll take credit for it, too.

So actually, I saw enough of this happen.

So a few years ago, I wrote an essay for Natural History Magazine called The Universe as the Artist Muse.

Dude, do you have a family?

Do you ever not...

You're always writing.

You're like, I wrote a book about that.

Well, because I got so much...

What I do, okay?

I inspired the symphony I wrote.

You're great, Neil.

I'm happy that I get off the couch, but that's great.

So no, it was an essay because I was impressed by how often I was being called by artists to get the latest image from the Hubble Telescope, where they wanted to find out the latest understanding of the Big Bang or black holes or Mars so that they can paint a scene, something inspired by it.

I mean, even as a comic, you know, artists tend to look at...

Where people, all artists, whether it's writer, comedian, or visual artists, you know, we tend to look at the whole world.

We look at everything, over, under, in, out.

I just don't think science was in that portfolio until recently.

Well, science is part of the world.

It is definitely part of the world.

In fact, it shapes the world.

And so, I think science has come a long way in terms of being felt by the general public.

And so, let's see what Bill Nye has to say.

Oh, Bill Nye.

Bill, he's my boy, Bill.

You know, Bill is...

Bill, he's got to set the tone.

He's a shaky little manic man with a...

Bill, give it to me.

Hey, Bill Nye, the science guy here.

When you think of a planet in your mind's eye, what do you see?

Many of us see Saturn, but no one could envision such a thing until astronomers, starting with Galileo, drew sketches of this and other worlds.

I've seen Saturn rings, Saturn brooches, Saturn ladies' pumps, dress shoes with jeweled Saturns instead of bows.

How sexy is that?

With images of distant stellar clouds and our so-called nearby worlds, we can make planetary art from photographs.

If you've never taken a bit of time with the Voyager spacecraft's pale blue dot, well, you must.

And thanks to a spacecraft named after another astronomer, Cassini, you can see our world through the thin rings of another.

You can see the Earth beyond the rings of Saturn, backlit by the sun.

It's a photo.

It's astronomy.

But for me, it's inspirational.

It's art.

This is Bill Nye hoping that after we're done StarTalking, you do a bit of star-looking at the works inspired by distant worlds and heavenly wonders.

That was very deep, Bill Nye.

Bill is deep in one minute.

That's a Bill Nye minute for you.

Yes, yes.

And when you think of the first of the artists to be fully scientifically inspired...

It's got to be Leonardo, Leonardo Da Vinci.

There's nobody like him before or since.

Here's a guy who was on top of science.

He was all over engineering.

He was in architecture.

And, oh, by the way, he painted on the side.

You know, this guy, and he used to do experiments in physics, physics experiments.

The word physics didn't quite ever was defined back then, but he would do experiments in motion and weights.

And wait, now he did this for his art?

Well, I don't know if it's for his art, but he did it in a way that then influenced his art.

I don't know if that was the point of why he did these experiments.

He was a smart, curious guy.

You're smart and curious.

You play with stuff.

So he was one of those guys that activated both sides of his brain?

Yes, completely.

If you did one of these scans on his brain, it would be firing at every cubic inch that was in there.

Great guy to date.

What's the matter?

I think he sounds great.

I'm just saying, some of these guys in history, I go, oh, he'd be Galileo, great boyfriend, Da Vinci, not so much.

Well, he's okay, because he'd be too distracted by his own thoughts rather than by you.

And I like someone who's manipulated easily.

Not someone like that.

That would not happen with Leonardo, for sure.

No, but tell me more about him.

So first he's considered one of those brilliant people who ever lived, and you look at his writings, all the subjects that he touched, geology, physics, biology.

And on the side, he was a painter, right?

And so one of my favorite parts.

You know about his, he drew a model for a helicopter.

It turns out it wouldn't work if you actually built it.

But he's thinking about flying.

He's thinking about flying, and not just saying, gee, wouldn't it be great if I had wings and I flew like a bird?

He's actually trying to draw a machine that could make that happen.

Oh, so he was one of the first people who started with machinery.

Yes, yes.

To bring machinery to the task of ideas, rather than just imagining that you had wax wings, like Icarus trying to fly to the sun.

He says, look, dude, you need some machines to do this.

And that's more like who I would date.

So you've got this.

And with Leonardo, he embraced all knowledge.

And with all of that knowledge, it infused into his artistic expression.

How did it infuse in his art?

Well, okay, did you know that he...

Probably not, but go on.

Okay, so he basically, well, he didn't invent perspective.

That's something that's been around since ancient Greece.

But it got lost.

It got lost until the Renaissance.

And Renaissance is French for rebirth.

And so it's the rebirth of...

And Leonardo was in the Renaissance?

Yes, he was.

Yes, he was.

I'm gonna show my ignorance.

Okay, so until then, let's go back a minute.

So let's go back to the Greeks and Egyptians and all these kind of people.

Okay, Egyptians, when they did hieroglyphics, they were flat.

Yeah, all those dudes were flat.

Right, right.

You look at them, they're all flat.

And you never see a three-quarter face of an Egyptian.

They're always side-on.

Yeah, you didn't see them walking into the distance.

None of that.

They're flat.

And there were arrows pointing like, then they went that way, then they went that way.

So they were flat.

Right.

And it's the absence of perspective that does that, right?

Okay, then who?

The Greeks?

Did they have perspective?

Yeah, well, so perspective comes in, but it doesn't really take off.

It's there, it's discovered, they know about it, and it's used in the architecture.

It's there, but you don't see paintings that make full use of this until the Renaissance.

And so my point is that the physical principles of light and optics and ray tracing, and in the case of Da Vinci, he studied the laws of physics.

They were not known as laws of physics back then, but he wanted to know how things balanced and how things would look if they were imbalanced.

Because if you draw something that your eye and brain told you doesn't quite look right, it's not as convincing to you.

So he wanted to make sure he understood how things worked.

I took art in college, and my mother is an artist, and as a kid, I remember one of the things she always used to make me do, and they make you do this in art class in school, or in college, they'd make you look at what you thought you saw and what you really saw, and that's what it sounds like you're saying, because sometimes what you think you see is not exactly what's there.

Because your brain is messing with what it is you thought you saw, and he's trying to get the basic data there so he gets it right.

My mom makes me squint, and you squint, you see what it really is.

You know who we have for this week's StarTalk?

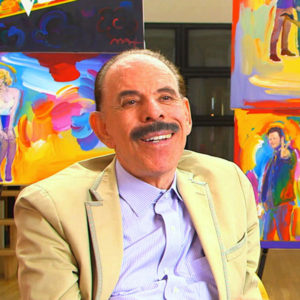

I spent some time with Peter Max.

Oh, that's a big clue.

And he's still around.

He's a big pop artist.

He's a pop artist, and did you know he's deeply inspired by cosmic themes?

I wouldn't be surprised by that.

Yeah, let's check out what Peter Max had to say.

Peter, I understand the universe inspires you.

Is that a recent phenomenon, or does it go far back?

It started when I was about ten, seven years old, living in China, and I was near Tibet, and I met an older man who start talking to me, do you know about the stars and the planets?

And I had no clue, and every day would talk about it.

And by the time, I think, five, six or ten days went by, that's all I would think about, and what I would go to sleep dreaming about it, thinking about it.

So, it took only a week for it to just infiltrate your mind and body.

Yeah, to jumpstart that.

And believe it or not, it just grew and grew and grew.

There's not a single day in my life where I'm not preoccupied with things about planets, stars, the universe, what is this whole thing.

There's not a day that goes by when I don't think about it.

I wake up in the morning and it's amazing, like some cosmic alarm clock opens my eyes and I think about the universe.

I don't think the bed I'm sleeping in, I don't care what day it is, I don't care what today I have to do today.

The first thing is the universe, the cosmos.

Then I gotta calm this down, and then I look at my sheet, what I gotta do today.

The first thing is the universe.

So you've got it bad.

I got it bad.

You got it so bad it's good.

Yeah, it's unbelievable.

That's why when I'm with you, see you on TV, talk to you, even hear your name, forgive me.

But I get so inspired by that.

He's so nice to me.

Forgive me, he says.

That's so beautiful.

You're his muse.

He didn't have to say that, but that was so nice.

So Peter Maxx.

If you remember Peter Maxx, he wrote all those love posters from the 60s, and yeah, and it's like, he was the artist of a generation back then.

Oh my gosh, you still see all the T-shirts that have the peace sign and the hearts, the big hearts that he did.

And I wanted to say what he said I thought was so sweet about waking up and how the universe inspires him.

Like he doesn't think about his bed.

That's what I'm saying, like artists are so neat because they think in such a bigger...

A bigger canvas, yes.

And the universe, I think, is inspirational because it's infinite.

I wonder if any listeners, if anything about science or space inspires them, either artistically or otherwise.

I know it inspires me, and I'm a scientist, it inspires Peter Maxx.

It inspires me.

And he's an artist, and Lynne.

And I'm, you know, something like an artist.

And you know, with Da Vinci, So call us, wait, call us.

Oh yeah, sure, I gotta give you the number.

At 877-5-StarTalk, tell us what inspires you from art, I mean, from science.

Yeah, yeah, let us know.

Because there are many people who are inspired, who are creating art, who are making a difference in this world.

And I'm charmed by that because, like I said, to see artists get mainstreamed in that way, if it becomes the subject of art, to see science get mainstreamed in that way, when science becomes the subject of artists, I think science has arrived in the culture, in the ways that no one had ever imagined for it.

Do you know what Leonardo?

You're just excited about scientists being cool.

Do you know what Leonardo did to try to become a better artist?

What did he do, kneeling?

He's drawing people, and so he dug up cadavers.

Really?

Dug them up, peel them open to see.

It's gross, but if you're committed to your art, you'll do whatever it takes.

What did he do?

He peeled them open.

See, this is, again, we give...

They're dead, why do they care?

They're dead, who's gonna know?

Jeffrey Dahmer did the same thing, and he didn't get credit for being, he said the same thing.

He killed them first, that's different.

He learned to kill them first.

They're already dead.

Oh, he just dug them up, that's fine.

Dug them up, who's gonna know?

He dug them up, peeled back the skin, looked at how the muscles came together, how they formed.

He wanted to know what was going on beneath the skin of his subjects.

Well, don't they have an exhibit now that bodies are...

Yes, which I haven't seen yet, but I've read about it.

You got downright giddy.

No, because I want to go.

I want to take my kids to see it, so they can see...

They're creeped out.

My kids are eight and 12, and they don't want to go.

You should not see that right now, Neil.

They're completely creeped by it, but I'm going to drag them kicking and screaming so they can see what bodies are.

Are you really?

It's human physiology.

And if you create little serial killers, I'm going to be surprised.

So that's maybe the modern version.

Take them to Madame Tussard's Wax Museum, where all the normal kids belong right now.

So here's what's interesting.

If we had the bodies exhibit, which is in a lot of the big cities across the country right now, where they have people formerly alive shown without their skin, and you can see how the muscles and all the rest of the body parts come together in different poses and shapes and forms.

Really?

So it's really like a serial killer Disneyland.

Well, no, creepy, demented serial killer Disneyland.

Yes, because serial killers just kill people.

You gotta be demented enough to peel their skin back and see what the muscles are doing.

But I do understand why Leonardo would have done that.

If body's exhibit existed back then, he wouldn't have to dig up cadavers.

And I just saw a thing on National Geographic, because you know all my knowledge of everything is from you or television.

I just saw a thing on National Geographic where they had found these pterodactyls, and they did that very thing.

They had found just the fossil, just the skeleton, and they took it and they put the skeleton through a CAT scan.

All right, all right.

Which I thought was really weird, but there was nothing inside, of course, because it was a skeleton, but they drew art, artistic pictures, and then they could figure out what would have gone in there by what was missing.

Isn't that kind of cool?

There you go, because you don't have a pterodactyl cadaver, a literal cadaver, so you do the next best thing you can.

What's missing, that's how you figure it out.

And you know, these bodies that are in the exhibit, they're preserved.

There are different ways you can preserve human flesh, and one of them is you'd sort of dip it in acetone, right, that gets rid of sort of the moisture and the water.

I mean, just so you know!

And then they have to sort of keep, then they have to like keep it shape.

So they infuse it with silicone, which then hardens the tissue so that then it can stay on display.

Like Pamela Anderson.

Well, she's a liar.

I don't know what fraction of her body weight is silicone.

I don't know about that.

Lisa Rinna, Pamela Anderson.

So they would not need to be prepped if they would donate their body to this exhibit.

Is that what you're saying?

Because they're pre-made for the exhibit.

Oh yeah, I'm saying they're gonna last for a long time.

They'll be around with roaches and cheese waves.

And Twinkies, don't forget.

You're listening to StarTalk Radio.

I'm your host, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson.

My day job is as director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York City.

We are live in Los Angeles and Washington, DC.

And I'm here with Lynne, Lynne Coplitz.

Give us a call if you have something about space that inspires you, space or science in general.

If you're an artist in particular or if you're just somebody on the street.

I want to hear what it is that might influence you because we'll hear more from Peter Max learning about how science infused his creativity.

Our toll free number is 1-877-5-STAR-TALK.

And we are live streamed on the web on startalkradio.net.

Let's take a break.

We'll be right back.

Whether you're a space cadet or a rocket scientist.

We want to hear from you.

The phone lines are open.

Call now.

This is StarTalk.

Welcome back to StarTalk.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, with Lynne Coplis, my co-host.

The space cadet.

Professional comedian.

Yes.

We'll make you a space brigadier general by the end of these programs.

Lynne Coplis, a professional standup comedian who performs around the country, Lynne.

And you've been gone for a couple of weeks.

I love you.

I'm so happy to have you back.

I'm happy to be back.

Neil, now before we move on, I wanna go back to Leonardo Da Vinci for a minute.

And we were talking about bodies and the bodies exhibit.

Cause he dug up bodies to get the artistic form of what he drew.

And then on the break, we were talking about the bodies exhibit now.

Yeah, during the break, yeah.

And then you told me a little something that I didn't know, which was that those were prisoners, like Chinese prisoners?

We're told that the bodies on display in the bodies exhibition, which is shown in many cities now, were not necessarily people who donated their bodies to this cause, that they were the bodies of prisoners who were executed.

Oh, that's much better, then.

I like that better.

So it became a little controversial because the prisoner might not have had a choice in the matter.

Who cares?

He was a prisoner.

No, I'm just saying, I'm just not voting for sides here.

I'm just saying that it may be as controversial as it was in Leonardo's day when he's digging up cadavers.

Now, wasn't it controversial when he was digging them up?

Yes, he was.

You dig up a body, and the body's a sacred burial grounds in a church yard or wherever people were, of course.

But people didn't, people didn't, did they know he was doing that?

He did it in the dark of night.

With an assistant who made nothing, probably.

And, you know, one of the most famous illustrations from Leonardo's era is the, you know, the Virchuvian man.

Have you ever seen this?

Is that the one with the man in the circle in the square?

Exactly, exactly.

What?

I never thought of it that way.

It's just like a little homunculus inside of a circle.

But then everything's got abs, Jesus, the Virchuvian man.

That's true, yeah.

Well, cause he's drawn by people who like muscles.

And have never been to Pittsburgh.

Have you ever seen that?

There's no abs in Pittsburgh.

You just performed there a few weeks ago.

Yeah, the great sports teams, but no abs.

The sports players have the abs, not the viewers.

Yes, exactly.

So, is this gonna be on their next, like, the tourist motto, visit Pittsburgh, no abs?

Don't worry about your abs, come to Pittsburgh.

So, talk to me about the Virchuvian man.

So, here's where you get into trouble.

Because if you have an aesthetic, okay, but if you wanna believe that somehow the human form is some epitome of aesthetics, this is what went into the Virchuvian man.

And so, you all remember this image.

It's this man with his arms outstretched and his legs slightly parted, and it's a perfect circle drawn around him, and the arms are just touching the edge of the circle, and his feet are at the bottom of the circle.

So, you're saying this isn't just art, this was to prove something.

It's to prove that the human form had some aesthetic beauty to it, because the circle was the thing of beauty.

And in the center of that circle, you know what was there?

His wing-ly?

No, his belly button.

So, what we learned.

Oh, I'm sorry.

What we learned.

What we learned was that some people don't have those proportions.

It was assumed that your distance from fingertip to fingertip equaled your height, and then that was considered the ideal form.

And then you actually measure people, and some people's hands are shorter, some are longer.

Mine are actually especially long.

Some people have a high ape index, it's what's been joked about.

If your arms are really long compared to your body height, my arms are a foot longer than my height, so I can touch your nose sitting where I am right now.

How do you know that?

Well, because you know.

So the point is, in that circle.

No, no, you don't know.

Did you measure them?

Measure my arm, the distance from fingertip to fingertip, yeah.

You're hilarious.

Yeah, it's 84 inches.

And so, I'm just telling you that it's not everybody, I'm not alone in those who don't fit the circle.

They're bigger now, right, they were smaller then.

Yeah, but if it's a proportion, it's just a bigger circle, everything would be in proportion.

So that didn't really turn out the way anyone had hoped, but it remains an iconic vision, it remains an iconic vision of what humans would have looked like.

And then there's this thing with the golden ratio, you remember that?

Many people have heard of it, but don't quite remember it.

It has a mathematical form, I'll tell you what it is mathematically, but it's more interesting artistically.

Oh really?

Oh really?

Mathematics is not more interesting than art.

Hmm, that's a new idea.

All right, so if you take a line segment, and you can split it exactly in half if you wanted, right?

Then it'd be half and half.

But if you don't split it in half, and make one segment a little longer than the other, okay, you want to cut it into two pieces where A plus B divided by B, A plus B divided by B is in the same ratio as A to B, as B is to A.

Now, that's what it is arithmetically, okay?

So, now you can write that out as an equation.

It's one plus the square root of five divided by two to one, okay?

I'm so sorry.

I don't want to be disrespectful, but I'm gonna shoot myself in the face if you keep talking.

What does this mean?

I'm just saying, so if you do the math, you get a ratio of one to about 1.6.

In other words, back then, if you designed form, you would design it so that the base was 1.6 units long, and the height was one unit high.

And that would feel aesthetically pleasing to you.

And that was called the golden ratio.

Oh, now that's very interesting.

You know what they've done lately?

Can they do that with your face too?

Exactly, they're measuring people's faces, the width of the face and the height of the face and the nose to the eyes to the mouth.

And the claim is those people where those measurements capture the golden ratio are considered more beautiful than other people.

I was gonna say that's very creepy because that movie Gattaca, that's saying those people are more perfect.

Well, this is the one where they make to genetically choose your offspring.

So you choose one that has more golden ratios and then more people will think you're attractive.

Yeah, but that's not fair either because in different cultures, in different places, the ratios are gonna be different, right?

Like if you go to Africa, facial features are gonna be different than facial features maybe in certain parts of America or Eastern.

Well, this is the challenge.

They claim they've done it for people all around the world and everyone focuses back on this golden ratio.

I have my, I'm suspicious of it, but I'm just reporting what they've said.

And it's fascinating that there might be some genetic.

It sounds a little Aryan to me, I don't like it.

That there might be some genetic propensity for that.

I don't like it.

And do you know about the, not only that, in Da Vinci's most famous painting is what?

Do you know what his most famous painting is?

Oh, don't do this to me, you make me feel stupid, Mona Lisa.

Mona Lisa, of course.

I have that in my room, she looks like a dude.

You have a copy of the Mona Lisa, let's get that straight.

Yeah, well, not the real one.

I mean, I live in a three-floor wall cup that smells like trash and says, wash me on the Sharpie marker on the wall.

I don't think the real Mona Lisa's in my apartment.

So, what, she looks masculine to you?

Well, you know what they found?

They were able to study the painting.

You can expose it to a certain wavelength of light that penetrates the top surface of paint, and you can see a whole other illustration below it.

And it's rumored that that was a self-portrait of Leonardo himself that was the first attempt at whatever he was doing on that canvas.

Oh, and then he painted his inner Mona Lisa?

Oh, well, I don't know.

Is that why you think she looks like a dude?

I didn't know that until you just said it, but yeah, she does look like a dude.

I look at her every morning.

She's right in front of my bed, and she looks like a dude.

Yeah, well, okay.

A sweet dude.

So this is Leonardo in drag is what you're saying.

Yeah, I'm just saying, it looks a little bit like there was a review back then.

But yeah, because she's got kind of a thick forehead, and she's kind of crossed over a little bit.

I gotta look again.

I gotta look again to check that out.

Put her in a review, is that in Vegas?

Let's, as you, That's interesting.

You're listening to StarTalk Radio, and for this episode, I spent some quality time with Peter Maxx, pop artist from the 1960s, and he's still at it right on through to today.

And let's see what more he has to say about how the universe has inspired him.

He's interesting.

We are part of something that is so enormously big.

You know, when you talked about the molecules in one glass of water, there are more molecules in one glass of water than there are glasses of water on planet Earth.

Well, that line that you gave me about this feeds me for the next six months.

I want to think about this at least once a day.

I love it so much.

Well, I'm happy to be your fuel supply.

So let me ask you, are you more influenced by science directly, or is there a bit of philosophy that folds in?

There's science.

There's the mystery of the science because there is so much more we don't know than we do know, and we do know a lot, and so that we must probably not know a billion times as much, but it's wonderful what we do know.

But I was also lucky in 1966, just about the same time, I met a Swami, a holy man from India.

So you would use pure science as your source of objects and imagery, but the philosophy is a means of how you would interpose them.

Yes, yes.

So it was nice.

Through meditation, I was able to get very, very peaceful and quiet, but through looking at the universe, I would get excited.

And so in between the peacefulness and the universe is where the art world lived.

That's Peter Max.

He's just so in tune with his own sense of art and self and science.

He sounds so like a cool hippie guy, like very like down the earth and calm.

He calms me just listening to him.

Isn't it?

He's got one of these calming voices.

It's so beautiful.

And you two, the two of you are like a glass of warm milk and a cookie.

You're listening to StarTalk Radio.

Our phone number is 1-877-5-StarTalk.

If there's some aspect of science that has influenced you, inspirationally, as a creative person or just in your thoughts, give us a call.

We have Nancy from Santa Monica.

Nancy, you're live on StarTalk.

Hi Nancy.

Hi.

I'm dabbling, I'm actually an environmental scientist, but I like art a lot and I've observed a lot of artists who have been inspired by environmental science.

And I thought I'd just share this something with you.

We have a bunch of art galleries here in Santa Monica called Bergamot Station, and there is this really cool exhibit on hyperbolic crochet.

And what this is, you guys were talking about Leonardo Da Vinci and perspective, right?

Well, that's about flat planes as a geometry.

Well, apparently, there's another kind of geometry that was, I guess, driving mathematicians crazy, the hyperbolic space, which is the geometric opposite of the sphere.

And I guess I was taken by the exhibit.

I actually photographed the captions here.

So in 1997, there was this Cornell mathematician who was trying to figure out how to model this geometry.

And so he wound up crocheting it.

And you wound up finding that corals, kelps, sponges, all these different kind of anatolical features, actually hyperbolic geometry.

So these artists have gotten together and crocheted these incredible kind of landscapes of these objects with hyperbolic crochet.

And I was at the exhibit at Bergamot Station.

So there are a lot of children now going around without mittens because the crochet effort is going to art.

I love crocheting.

It's very difficult, but it does have a lot of that spiral, and it is very interesting.

So are you saying that crochet is the natural artistic way to express these forms of nature?

Well, crochet was a technique that humans could use to model this geometry, which was very hard to do mathematically otherwise, or I guess even on a computer.

Well, that's very cool.

So anyone near Santa Monica, go check it out, definitely.

That sounds so interesting.

I'm going to look it up online.

Thank you, Nancy.

Thank you, Nancy.

You know what I like about that, too, is because if you're using yarn or whatever, which you use a rope to crochet, that's great for studying the body, too, because it is like tendons and muscles.

Oh, how it holds together and how it doesn't.

Yeah, you can pull it and twist it and make it do things that you can't do with just charcoal, and it brings in perspective.

You'd use yarn as a substitute for muscle.

It brings in perspective.

Shut up, Neil.

I have lots of crochet things.

I just told Neil to shut up.

One other thing about perspective, another very famous painting is The Last Supper.

The Last Supper is one of the most famous.

Oh, Jesus' Dinner Party.

Jesus' Last Supper.

They call it supper rather than dinner.

I like to call it Jesus' Dinner Party.

I just love a man that throws a dinner party at the end.

If you look at that, there are lines of perspective that reach what they call a vanishing point.

The vanishing point is where all the lines that are horizontal in a room or in a painting end up focusing down in the backdrop of the painting, and it focuses right on Jesus' eye.

Really?

That's very interesting.

So wherever you are in the painting, the lines take you right to the center of his face.

For those who don't know, when you're drawing or painting perspective, a vanishing point is one of the first things you draw so that you can...

Because everything else works into that.

Exactly.

So that's very interesting that the vanishing point, so that was no accident that the vanishing point was Jesus' eye.

No accident at all, and plus his 12 dinner guests.

He was the center of the whole thing.

We have a tweet, but you can tweet us at StarTalk Radio.

We have a tweet.

Someone asks, do you think Georgia O'Keeffe's paintings are a combination of science and art?

And anatomy.

They're vagina flowers.

No, they're flowers.

They're vagina flowers.

Oh, come on, they're vagina flowers, tweeter.

They're flowers.

They are not flowers.

Look at them.

Oh, please.

Look into those flowers.

They're not just flowers.

You know what, Neil?

Okay, okay.

I'm just...

This is what annoys me about men.

Sometimes a flower is just a flower.

Well, sometimes it needs you to look for the G-spot on it.

So what we're saying is Georgia O'Keefe took the flowers of the Southwest and folded them with her knowledge of human anatomy to create a whole new expression of...

a whole other way to communicate with the viewer.

Yeah, I think it's what George O'Keefe and many artists do, great artists do, is that they make you look at something a different way.

They make you see the other possibilities in it.

Then that...

Okay, all right.

I'll give...

Other possibilities.

Yeah, and I think Leonardo did that.

I think all the great artists and painters, and they've all done that.

Writers, they've taken things that everybody looks at every day, and they've twisted it and showed you other sides to it.

We've got another tweet.

They're asking, is the golden ratio, which we talked about a moment ago, only about aesthetics, or is it indicative of the health of an organism?

And that's a fascinating point.

What a great question.

What kind of geniuses do we have listening to this show?

My family's clearly not tuning in.

So, no, what's good about that is, if the aesthetic is sort of hardwired into our brain, and we identify beauty that way, and then you turn ill, or something happens to your bodily form...

Don't put the horns on me.

You pointed at me.

And if you turn ill, then your body starts taking a shape that does not fulfill that golden ratio, and you look less attractive to others.

It's a fascinating concept there.

So maybe it is hardwired.

I'm angry.

So my question is, I don't know the answer to that, but it's an intriguing possibility.

Like osteoporosis.

Yeah, exactly.

Your bones start becoming misshapen, and you no longer fulfill the golden ratio.

Well, I think there should be a golden ratio for different ages.

So this should be like a silver ratio, a platinum ratio.

Yeah, just like the average, what your average weight should be or whatever.

It should just be like, here's the silver ratio.

That's an excellent, excellent thought.

The platinum.

Excellent thought.

We've got some more of my interview with Peter Maxx.

I was in his studio in New York City, and he's got this huge studio where he's still painting.

He's still doing it.

The guy is still doing it.

Why didn't I get to go to this?

I love Peter Maxx.

You didn't ask.

Let's see what more Peter Maxx has to tell me.

While I was a realist, and I started painting realism like Michelangelo, I couldn't get any work.

No galleries were interested in it, no museums, nothing.

And I used to sit in a little cafe, which back then was almost like, what is a Starbucks today?

And I would make my astronomical drawings every day because I loved it.

And I had maybe a hundred little drawings with me, and one day an art director said to me, Peter, what's this on the bottom of your portfolio?

And I go, oh, it's nothing, because I was shy, I was a realist, I was a classical guy.

Because at the top of your portfolio was all your realistic.

Yeah, I wanted to be like Michelangelo, I wanted to be revered as like, because I was so good in realism.

Anyhow, and one day he said to me, what's this on the bottom of your portfolio?

I said, no, it's nothing, it's nothing.

And he insisted I take it out.

And when he looked at it, he went, oh my God, this stuff looks unbelievable.

Hey guys, fellas, girls, come over here, see what this guy does.

And I walked out of there for the first time in my life with 14 projects that paid like a few hundred dollars each, which was today like a few thousand each.

And when I delivered them about 10 days later, I walked out of there with 22 projects.

And in the next 18, 20 months, I won 66 gold medals in art and design for my creativity and for my inventiveness.

And I suddenly realized that the stuff I was doing, which was these cosmic characters and cosmic stars and cosmic runners and all these characters with wings, that I invented only because of my interest in the space area, that I invented characters that lived there that really weren't anything I could see in the regular world.

So it's fair to say that the universe birthed your career as an artist.

Completely.

So you want to be a great artist?

Study the universe.

I think that's very cool that that's his inspiration.

Yeah, and so rather, it wouldn't have to be the universe in particular, but I think it's fair to say that you can be a new kind of an artist or as an artist you can reach another dimension of reality if you come to it with some kind of science literacy.

I think it is fair, but I think the other thing that our show keeps bringing up is that science makes you ask questions.

It keeps you asking questions.

Probing the nature of reality.

I think when a creative person keeps asking questions, it keeps broadening their view of things.

And that's what happened to him.

He kept asking questions and he kept creating these characters and people built on that.

And it's not just science ideas.

There's math even beyond the golden ratio that we talked about earlier.

There's algebra.

Look at the Matrix.

Movies and things are being built around this whole thing now.

Exactly.

And there's a branch of algebra called linear algebra, which you don't normally greet that in high school.

But you can take classes in it in college, where there's 3D computer games that are enabled because of a huge mathematical engine that's driving them.

Oh, yeah, I guess so.

Like Grand Theft Auto.

Because of science and math, you can kill a hoe and steal a car.

I haven't checked the math engine on that particular game.

But it allows them.

What it does is they're trying to create a virtual world for you that you move through.

And if you're stealing cars in it, fine, that's your virtual world.

But the perspective that changes as you run down the street and as doorways open and as corridors show up, they have to calculate at every split second what the new scene looks like as you travel through that world.

And what it will look like if you do this move or that move.

Exactly.

They don't know what you're going to do.

So it has to be ready for that.

And that's the computing power.

Exactly.

Lara Croft Tomb Raider.

When you dive in the water, all of a sudden you're in the ocean and the music stops.

Do you want to be Lara Croft?

No, she's way too active.

I got to admit I liked the movie when I saw it.

I did, but the video game is very active and annoying.

At one point I just started jumping off the slide.

But here is what concerns me as an actress, aspiring actress in comic.

You know, CGI now, computer graphic imaging, is really taking over.

I went to see Bolt, the 3D, when it was 3D, with my friends.

Bolt is with the dog?

Yeah, with my friends' sons.

And I have to grab little kids from out of nowhere so I can go to these movies and not look scary.

And I went to see it.

It was great.

But when I was a kid, 3D movies were not as intense as they are now.

I mean, they're so realistic.

And as an actress, it started bothering me, Neil, because I started thinking, wow, when are we going to fade out?

Like the way talkies took over silent films.

I'm finally getting acting roles, and I'm done.

They're going to start just drawing people.

Yeah, you draw people and animate them in 3D, and then they won't need you anymore.

So isn't there a chance that regular actors and actresses are going to become obsolete?

You know what they can do?

They can fully scan your body in various motions and then fully get you to read like a whole encyclopedia of words, and then they have all your vocabulary, they have all your body motions, and they can just cast you in a 3D animated movie.

So they might not need us anymore.

No, yeah, you just sort of sell your body that one time, and then you get used later on.

Wow, I know there are people in LA listening to this show right now.

If this scares you because you're waiting tables and you're thinking, what now?

Call us at 877-5-STAR-TALK.

If you're worried about being out of a job, is that what you're doing?

Yeah, I mean, some of the science stuff, when it comes into the creative forum, it scares me.

Because, like, for example, I don't like nude digital film.

I hate it.

Nude digital film?

No, the digital film versus like 16-millimeter things.

Oh, okay.

Let's shoot everything on digital.

Now all of a sudden, I don't want to see people with lines in their face.

I can see that in the mirror myself.

I want pretty people.

I want the old grainy imaging.

I want the Barbara Walters lens that looks like it's got Vaseline over it.

That's what I want.

The soft-focus lens.

Yes, thank you.

Well, you know, photography is a, you know...

Did I make you nervous?

All of a sudden, Neil's like, I'm never going to be on the view.

What has Lynne done?

We're going to go to break, and we're going to come back.

Give us a call at 1-877-5-STARTALK, and we're tweetable at StarTalk Radio.

And we'll be right back.

And we're going to talk about photography in the universe and how that's inspired whole generations of artists and movements, social movements, simply because of images we've obtained from the night sky.

See you in a moment.

Bringing space and science down to Earth.

You're listening to StarTalk.

StarTalk Radio, Neil Tyson on the line here.

We've got Lynne Coplitz, my co-host.

Hello.

We've got a caller who called into 18775 StarTalk with our question about the relationship between science and art and inspiration.

Who is the muse for whom?

We have Rick from LA.

Rick, you're live on StarTalk.

Hi, Rick.

Hey, how are you guys doing today?

Well, thank you.

We're doing good.

How are you doing, Rick?

Thank you.

So what you got for us?

Well, you're talking about how science has inspired art over the years, and I was just wondering if you could think of any examples where art has inspired science.

Oh, that's a good question, Rick.

Well...

Scientific discovery.

Yeah, here's the best I could do for you there.

For example, before the era of photography, when people nonetheless had telescopes and they wanted to be able to tell others about what they saw, they had to draw what they saw.

So they needed an artistic talent just to communicate their science to other people.

And if they were not good at their art, they'd be showing something that was not really what they saw to other people, and that would confound any attempt to have sort of a level-headed assessment of what was going on.

Well, also, the constellations.

At first, they came up with, like, what the stars, they came up with pictures, correct?

Yeah, but there's no science anywhere in that.

No, there's just...

Well, no, they're connected dots points.

I mean, they are scientific subjects themselves, but things we would only learn much later, long after anyone was drawing pictures with them.

Okay, so, Rick, the answer is we don't really know.

No, no.

Let me offer a little insight.

I can say that artists, not to speak for artists, because I don't claim myself among them, although my brother is an artist, I can say that all artists I know are driven, often, if not all the time, by some aesthetic.

And it's the aesthetic that drives, that fuels their attempt to create a form.

And I can tell you, without hesitation, that as a scientist, we approach the universe, we approach the natural world with a similar expectation that what we're going to discover is something aesthetically pleasing, something beautiful, something that will make you say, that is nature at its finest.

And so, I can tell you that we share a common driver.

But whether or not there's some art that inspired a scientific discovery, it may be that it doesn't...

But also, if you're talking about what kind of art you're talking about, because we've already discussed on this show that there are films that have probably, in television programs like Star Trek, that have inspired scientists.

Exactly.

So what happens there is, the art...

Triggers someone to be interested in a subject, because it affects them in an emotional way, and then they become charged, and then they want to learn about the science.

I think what we're saying is we all need each other.

Kumbaya.

Hold that.

So, Rick, thanks for calling in.

And we still have some more from Peter Max.

Peter Max, you got to love him.

And like you said, Lynne, he has such a soothing voice.

I could listen to him all day.

Let's see what more he's got to tell us.

I was in Cleveland.

I had an art show.

And I wake up in the morning, and I go back to sleep, and I wake up again at about 10.30, and I'm flip-flopping around the TV set, and suddenly I see Neil Tyson with his khaki pants, rolled up past his knees, squatting down, lifting up a handful of sand, and saying, you see all the sand?

There are 10,000 beaches in the world.

They're like 10 or 20 miles long.

And then he lifts up another big pile full of sand, and he said, as it's running through his fingers, he said, for every grain of sand that we have on these 10,000 beaches, there are more planets in the universe.

And I meant, oh, my God, I can't...

This is so big, it's so gigantic, that all the grains of sands in 10,000 beaches that are like probably 10 feet deep and 10 to 20 miles long, that there are more planets than this.

The first thing I looked is for my phone.

I found Neil Tyson's phone number and I called him up and said, is this real?

He said to me, it's probably bigger than that.

Well, I'm honored to have blown your mind without drugs.

What do you think of that?

It is like there's nothing that's nicer to be blown away by than the cosmos, the universe, these complete unbelievable facts that exist.

And the more you think about it, the more you dream about, the more it starts making sense.

And you still know that you're just this little microscopic little thing in the universe, thinking about all the bigness, the largest thing.

I mean, isn't it true now that because of this thing they call the string theory, they think that it could be other universes?

Are there a couple of ideas that lead to the idea that there could be a multiverse, and we're just one bubble within an uncountable number of other cosmos?

Just like when Hubble discovered the first few galaxies.

Exactly.

And now they're discovering maybe more universes.

It's philosophically the same thing, because back then we imagined it was only one galaxy, and then he discovered a universe of galaxies.

Yeah, you got it.

There must be a place you can hide.

It is too big.

It's too big to imagine.

You know, sometimes you got to take a tranquilizer to calm it down.

It's just so amazing.

Okay, Neil, I didn't think this could happen, but Peter Max made me like you more.

Really?

So I got dibs from Peter Max and now it's...

He actually makes you sound even cooler.

I didn't know he'd go off on that that way.

I was just trying to get some...

It was so sweet that you touched him so much...

.

content for our show, but I didn't know that.

And he's an amazing artist, an amazing influence in person, and that's really neat.

Yeah, you know.

I have a homeless person in my neighborhood who says I really inspire them.

Was that that guy that was on the sidewalk when I visited you the other day?

The lady who wears these big, crazy Erykah Badu wraps and her hair.

So photography can inspire people.

Do you remember?

I don't know how old you are, Lynne, but in 1968, Apollo 8 went to the moon.

It didn't land, but it actually circled the moon and came back and took a picture of Earthrise above the lunar landscape.

I was very little when that happened.

Okay, but you've certainly seen that photo.

It's called Earthrise.

By the way, Earth does not rise on the moon because the moon doesn't rotate compared to the Earth.

So Earth is just always in the sky.

So the picture misrepresents what actually happens on the moon.

It rose because they were in orbit around the moon when they took the picture.

Okay, that's great.

Yeah, thanks.

What I'm just saying.

No, no, I'm saying that's great things.

Is the moon camera different than a regular camera?

Bigger and more expensive and take better pictures than most cameras you'll ever see in your life.

Do you have one?

No, I don't.

You do, don't you?

So what I'm saying is that picture that showed Earth, without any lines of continents or states or cities, it was just this blue orb, juxtaposed as part of the scenery of another world, transformed our understanding of our place in the universe.

And the modern green movement is traceable to that photograph.

And so there's scientific photograph that became iconic art that influenced a generation of people to take action.

I just had to share that with you.

Interesting.

Now the Hubble images and things, is that the same kind of camera?

No, it's a digital camera.

That was a regular sort of film camera back in the days of Apollo 8.

And now Hubble pictures is digital.

It's a very expensive version of the detector that's in the camera that all of us have, the digital cameras that we all use.

It's called a CCD, charged coupled device camera.

So you asked, I'm just telling you.

You asked.

Did I volunteer that?

You asked.

LOL.

You asked.

And so the Hubble photos are today's generation of exposure to the rest of the world.

Which are better?

Oh, definitely digital pictures are far superior.

Because they're more accurate.

They're far superior.

In terms of romance, do you know there's a scene in the Carl Sagan film Contact?

I don't know if you saw the film.

Do you remember where Jodie Foster was taken by the aliens into their distant land, and she's looking, and it's so beautiful, and you remember what she says?

No.

She says, because she's speechless.

By the beauty of it all, she says, they should have sent a poet.

Oh.

That's political in itself.

Poetical or political?

Whatever, poetical.

And other thing.

I'm a big fan of...

I'm not Peter Max.

You better watch what you say.

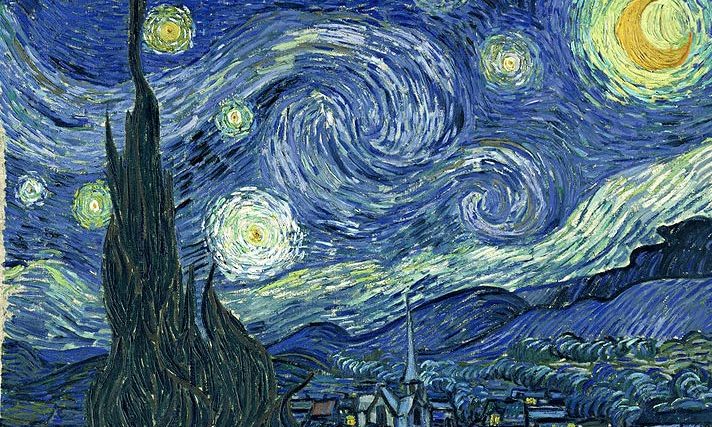

I'm a big fan of Van Gogh's Starry Night.

Oh, you think?

It's inspired a song.

Just so everyone knows, who doesn't know Neil, Neil has Starry Night stuff all over his office, everywhere, like pillows, books, which is great, because it's beautiful.

And there was the cover of one of my books, too, because it's a Starry Night.

It's an artist who, he could have named that painting Sleepy Village.

Neil, you know what?

We had this argument before.

No, we couldn't.

It's all stars in the sky.

It's about the sky, not about the village.

I'm agreeing.

So the man came through.

I'm totally with you on that.

And then there's other art that goes into, you know, the ceiling of Grand Central Terminal?

Yeah, you took me there and showed the ceiling to me.

Yeah, well, you didn't need me to take you there.

It's Grand Central Terminal.

I know, but I never really looked up at it until you took me there.

Oh, that's different.

Okay, so that ceiling, did you know that all the stars are backwards?

That pissed me off when I discovered that.

And who did that?

I forgot.

Paul Haleu from 1912.

Was he dyslexic?

A French artist.

I think he was not sufficiently scientifically literate to know that the image of the sky he was looking at in a map was the reverse of what he had to put on the ceiling.

Or he might have been dyslexic now.

It can't be that dyslexic.

Dyslexic is flip a few letters or a few words, not an entire sky.

So there's no excuse.

I don't forgive him at all.

I wonder if he still got paid.

And you know, with those Hubble photos, some of the colors are vivid.

They can represent colors that you would see if your eyes were huge and if your retina were sensitive to the filters that the Hubble Telescope uses.

You wouldn't necessarily see what Hubble sees.

You would, however, if you can tune your eyeballs in the way we tune the Hubble Telescope.

I don't get that.

What does that mean?

So it means the colors that I think I see on there are not the colors that really...

That's great.

If you had special eyeballs, you would see it that way.

You would see it just that way.

We have feeble eyeballs.

So in space, when I see it, if I was in spacecraft looking at it, it wouldn't look like that.

No, it would look like something else that was commenced with your eyeballs, but in Hubble, we want to see...

That's aggravating.

Well, I'm sorry, but it's just, you know, what happens when people put on makeup before they get photographed?

It's not what you really look like.

It's something else.

I'm just letting you know.

But if you were there on the planet, would it look like that?

It would look different.

Would Mars really red?

Yes.

You're getting angry with me.

A fast clip of Peter Max.

Our final clip with him.

Let's see what more he has to tell us about how he's been inspired by science.

I want to make an animated film.

I told you about it earlier.

And this film has a lot to do with the universe.

And it's with, like, us suddenly connecting with another species from far, far away who have some common interest with us.

And it's a beautiful, it's a musical.

It's a two-hour musical.

And I'm about maybe halfway through designing it, conceiving it, and I'm going to go to some of my friends in Hollywood and see how I can get it made.

Well, we've got to get you back when that comes out.

Yes.

Listen, Peter Max, it's been great having you on StarTalk.

And thanks for your hospitality, inviting me into your studio where I'm inundated by paintings ready to fall on me.

This place, you need, like, three more floors of this warehouse.

Thank you, thank you.

We just have a couple floors here with about 100 people, but it's my playground.

In the morning, I can't wait to get here.

At night, I don't want to leave.

That's how all jobs should be.

Peter Max, thanks for being on StarTalk.

That was Peter Max.

I love him.

Why do you love all the guests that I have on the interview?

Well, I don't know.

I think he's my new favorite.

Until our guest next week, she's my real favorite, but it's really awesome.

So I don't know if you know that NASA is not unmindful of the fact that art matters in our culture and in society.

So it's not just fighter pilots, fly boys, and scientists they send into space.

They send artists?

Well, no, they don't send artists into space, not yet, but there's an Arts in Space program where artists are invited to capture the discoveries of NASA, the voyages of NASA, and whatever is their artistic means of expression.

And it was started in 1962, and they've commissioned artists such as Norman Rockwell and others, and it chronicles the history of space exploration through the eyes of artists and others.

And there's more than 2,000 works of art by 350 artists in their archives.

That's interesting.

And listen, next week, this has been a great show, but next week, tonight, we need everyone to watch the Joan Rivers rose.

Joan Rivers is being rose.

She's a buddy of yours apparently.

She's my dear friend, and she's on our show next week.

Yes, indeed, thanks to your connections.

I could have never had access to this woman.

She's an icon of comedic.

She's going to be riffing on all the science that we're trying to take seriously here and tell us where that fits and where it sits.

You've been listening to StarTalk Radio.

Good show, Neil.

Funded by the National Science Foundation.

We'll see you next week.

Keep looking up.

See you next time.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron