Neil deGrasse Tyson’s exclusive, one-on-one conversation with whistleblower Edward Snowden – via robotic telepresence from Moscow – concludes with a deeper dive into metadata, personal privacy and covert communications. Join us as Edward takes us further down the rabbit hole, where countries spy on their own citizens to protect them and “mere” metadata can be more intrusive and invasive than the actual content of a phone call. Decipher the differences between symmetric encryption, asymmetric encryption and secret sharing schemes. But this episode isn’t just advanced math and n-dimensional matrices – Neil and Edward leave Earth behind and dive into the wavelengths of pulsars and cosmic background radiation in search of the perfect random number generator for an ideal seed value. Plus, Neil and Edward discuss the difficulty of separating the signal from the noise, both in astrophysics and in government mass surveillance.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Welcome to StarTalk Radio. I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist. And as many of you know, I also serve...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Welcome to StarTalk Radio.

I'm your host, Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

And as many of you know, I also serve as the Director of New York City's Hayden Planetarium.

The Frederick P.

Rose Director is the name of my chair, and that is part of the American Museum of Natural History, right here in New York City.

You can follow StarTalk on Twitter, at StarTalk Radio.

You get all the news and buzz of what we're up to and what the shows are coming up.

And also on the web, we've got nice pages, Facebook page, StarTalk Radio, and also our own website, startalkradio.net.

Also, I tweet, if you're interested in my own personal cosmic brain droppings, at Neil Tyson.

Last week on StarTalk, we broke format completely.

It's rare that we do this, but when we do, rest assured that something or someone out of the ordinary has justified it.

And you really can't get more extraordinary than an exclusive interview with an international fugitive via a remote control robot.

This is the second and final part of our special edition of StarTalk, featuring my one-on-one conversation with none other than Edward Snowden.

Again, I'm not accompanied by my usual comedian co-host.

There's no in-studio expert.

Instead, we're going to listen together as Ed and I share our ideas about encryption, privacy, and what all this has to do with our basic human rights.

In case you missed last week's episode, I'll just remind you that Ed Snowden is a CIA agent turned international fugitive and has been a household name since 2013 when he leaked secret documents from within the National Security Agency, better known as the NSA.

These documents unveiled the government's top secret mass surveillance program aimed at collecting huge amounts of personal data, especially via phone records, from all United States citizens, not just the ones that were particularly suspicious in their behavior or activities.

And this wreaked havoc in social media and in mainstream media, and many US citizens found themselves betrayed and invaded by their own government.

What Ed did was, by any definition of the word, brave.

Whether or not it was right is a matter of whom you talk to.

Less than a month after the British news source The Guardian released Snowden's revelations, the United States charged Ed with theft of property and espionage, leaving him with no choice but to leave his entire life behind and seek asylum somewhere.

In this particular case, Russia.

Our old Cold War enemy, Russia.

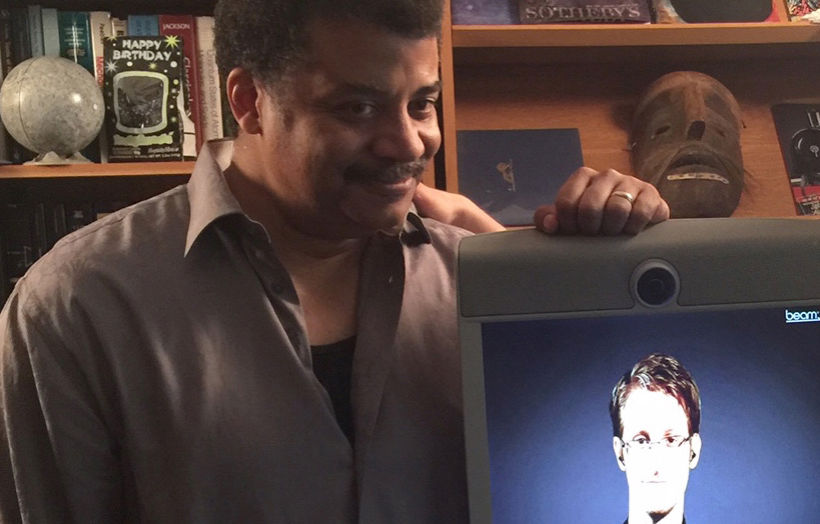

Snowden is still in isolation as we speak, but being the geek that he is, he found a clever way to communicate with me right here in my office at the Hayden Planetarium.

He literally wheeled into my office as a bot, a robot.

The voice you will soon be hearing emanates from his virtual face displayed on a BeamPro remote presence system, which is essentially like an iPad on wheels.

He manipulates it directly from Moscow, and it's where he's been offered asylum and is currently in exile.

And you know it's him because I say, can you nod?

And he can swing left, swing right.

He can control this thing.

So the bot itself had a certain presence in this interview, even though all I saw of him was his head.

Now, it seems everybody has an opinion about Ed Snowden.

Some call him a traitor.

Some call him a national hero.

He's worshiped.

He's despised.

He's praised as an activist.

He's criticized as a criminal.

And again, it all depends on who you're speaking with.

Personally, I choose to think of him as a card-carrying member of the geek community.

And I speak to him not as an interviewing journalist because that's not what I am and you get that from other places.

But I interact with him as a fellow geek.

So let's go to the first part of that interview right now.

So you've been in Russia for a while, and are you writing shirtless with Putin in the woods?

I actually just finished that up about 15 minutes.

And then we jumped out of airplanes.

So I expect you just buzz, right?

So Ed, I tried to find you on Twitter.

What's your handle?

I don't actually have one yet, but I got to say I follow your Twitter.

Well, thank you.

Thank you.

But still, you kind of need a Twitter handle.

So like, at Snowden, maybe?

Is this something you might do?

That sounds good.

I think we got to make it happen.

You and I have a Twitter.

Oh, nice.

Nice.

We get the legal to approve your every move here.

But if they give you that thumbs up, we're good for good.

Your followers will be, you know, the Internet, me and the NSA will be great.

So I think I understand where you're coming from now, but I want to hear from you.

You have government service in your blood.

You join an intelligence agency that's all about gathering information.

And then you tell everybody the secrets.

So that kind of sounds to me like I'm imagining a police officer showing up at at the Indy 500 and handing out speeding tickets.

This is not the place to hand out speeding tickets.

Everybody's driving fast here and everybody here knows that.

So what was your tipping point there?

Because you were full, you were fully, you were all in.

You were all in, in this business.

And now to come around 180 and say, no, I'm not, are you handing out tickets at Indy 500?

No, I do believe in the value of national defense, of intelligence gathering, in line with the context and the value of our society.

What I revealed was not simply secret information for voyeuristic intentions or anything like that.

And I never published a single document on my own.

What I did was I worked in partnership with the free press, the institutions of journalism that are a fundamental part of American society, to reveal not simply the operations of intelligence, of how the intelligence community works, but unlawful or immoral programs, which now courts have agreed with me, broke the law.

Even within the CIA or the NSA, no one in the US is supposed to be above the law.

In June 2013, the President of the United States, when these programs were first revealed, said, you know what, don't worry about this, guys.

It's not that big a deal.

I think we've drawn the right balance here.

In January of 2014, he said, in fact, these programs need to end.

The mass surveillance, sort of the bulk collection of Americans needs to stop, and I'm going to call on Congress to do it.

Now, that was obviously sort of passing the buck there, but it's a fundamental change in recognition of the value and the necessity of the programs.

When we talk about national defense, when we talk about national security in real terms, not in political or rhetorical terms, we need to think about the concrete difference they make.

We need to think about is this consonant with our values and is this application of authority, is this application, this intrusive application of force necessary to the protection of our society and proportionate to the threat faced?

It's the same reason that we don't watch nuclear missiles at people who sneak through immigration.

You know, there has to be some level of reason there.

And what I think we've seen is that because these programs were born in secret, outside of the review of open courts, outside of the review of the majority of Congress, and even the president himself did not know the full details of everything that's been revealed since 2013.

For example, it's claimed that he was surprised when they found out that the NSA was monitoring the cell phone of one of his closest allies.

And so we need to think about where we draw the lines there.

And I think it's because we have a fundamental tension between the NSA's offensive role, which is hacking into people's communications, undermining their security and trying to listen in on them, and also protecting our communications domestically.

And what has happened, particularly in the post-911 period, is we've seen a slide that's increased in velocity and force from a national security agency to a national surveillance agency.

And that's not in our nation's interest, because when we think about, for example, a global spy war, let's say cyber security, you know, the topic of the day, and we think about the research and development budget of the United States, which is larger than any other country in the world, and we compare it to some of our competitive assets.

And not as a percent, just as a total, total money it's large, but not as a percent of the total, is that correct?

I mean, total dollars, it's large, yes.

I don't think anybody would contest that the United States has the most advanced technology companies, research initiatives and things like that, at least when it comes to industry.

And yet, the NSA is weakening the security of Internet systems and standards upon which we rely to an equal or greater measure than our adversaries.

You can analogize this to an example where the NSA finds a way to build a back door into every bank vault of every country in the world and in a sort of global economy where there's only the United States and China.

We've got $90 and they've got $10 in a $100 economy.

Every time you successfully steal from the other guy, you gain 10% of their gross domestic product, their $10 and $9.

When we hack China, we get $1.

When they hack us, they get $9.

It's more important to us to protect our systems because they protect more valuable assets than it is for us to weaken the security of our adversaries.

When I think about government surveillance, my knee-jerk reaction is Cold War Russia, Cold War Soviet Union.

It's when this became global, this concept of the government spying on its own citizens.

It's almost a cinematic trope.

Spies with suitcases and mustaches, hidden in shadows behind telephone booths and alleyways.

They'd be observing you surreptitiously, but clearly not because we all knew they were there.

But obviously, this picture is far different from Ed's reality.

And I asked him about the difference in surveillance programs between then and now.

Here's what he said.

How would you compare 21st century United States to Cold War Soviet Union in terms of surveillance on our own citizens?

You know, I haven't really thought about that too much.

When I think about that, I wouldn't compare them directly.

But what I would say is there has been an interesting cultural change in the political circles of our country, which is that during the Cold War period, we had an adversary that we compared ourselves to constantly.

And it was self-evident to us that the massive intrusive surveillance programs of the Soviet Union showed us there were undeniable evidence of the superiority of our moral system, that we rejected those programs, even though we had the capabilities, even though we could do it more, even though we could do it better.

We turned away from it because we said that's not who we are.

We are not going to watch the daily activities.

We are not going to peer into the private lives and private records of ordinary people who have done nothing wrong.

In the wake of the Soviet Union, after their collapse, there's been sort of a vacuum of adversaries.

Nobody can really challenge the United States the way that it happened back then.

And because of that, I think we've lost a little bit of a competitive honesty where we were rating ourselves against everybody else in the world, or at least the challengers, because we couldn't ignore it.

Now, today, when we talk about our threats, we're talking about people like Al Qaeda, people like ISIS, who there's no question of moral superiority because they're chopping people's heads off and lighting fire.

When I think of the Cold War Soviet Union, I think of people in trench coats following you down the street.

But today, they're not people in trench coats.

They're surveillance cameras in the street following me down the street.

What's the difference?

The difference in technology is something that politicians have used recently to claim that we shouldn't worry anymore.

For example, they say, we're not listening to what you say on the phone.

We're just keeping track of who you call, how long you call them, and that kind of thing.

We got to wrap up this segment of StarTalk.

We've been following my exclusive interview with government whistleblower Edward Snowden, who spoke with me through a robot that he controlled from his Russian asylum.

Next on StarTalk, we're going to get more deeply into the science of encryption technology.

And Ed even had some questions for me about how to hide secret messages among the electromagnetic noise of the cosmos.

Welcome back to StarTalk Radio.

We've been following the second part of my exclusive interview with CIA agent turned whistleblower Edward Snowden.

Two years ago, Ed spilled top secret information to documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras and journalist Glenn Greenwald, who published an article in The Guardian revealing the NSA's mass surveillance program.

This triggered an upheaval of public debate across the world.

The US intelligence agencies were effectively and I suppose understandably outraged, and Ed was charged with espionage.

Meanwhile, the authors who leaked Ed's information to the world won Pulitzer Prizes for public service, also George Polk Awards and other such prestigious recognitions.

So, apparently the media had a slightly different opinion than the rest of the government on this issue.

And it was the following year that Laura Poitras directed her documentary film called Citizen Four, unraveling the entire series of events, from the moment she received Ed's encrypted emails to the moment Ed found himself in asylum, isolated in a foreign country.

It won the Academy Award for Best Documentary.

And when I saw the film on HBO, it was an unbelievable sequence of events that you think, oh, this must have been scripted by some espionage writer from the Cold War.

But in fact, no, it was real.

It actually happened.

And we ask ourselves, is this happening today?

This, the second decade of the 21st century?

So I was left with these feelings of, what is the world we're living in today?

I had no idea this was going on.

Alright, let's talk about a simple cell phone.

What can the NSA do with it?

Two years ago, we would never even have thought to ask the question.

But after Ed leaked thousands of top secret files to the press, we now have the answer as well.

And it isn't easy to sit with.

They can do whatever they want.

This means they can turn it on, turn it off, access our apps, turn it into a microphone, watch us check our mail.

But this sort of content monitoring is relatively reserved for individual targets, as I understand it.

But what Ed is concerned about is the wider net cast over every US citizen to scoop up our metadata.

I ask Ed what the word actually means.

So let's go now to the one-on-one conversation Ed and I had together in my office, here at the Hayden Planetarium, when he wheeled in, in the form of a robot that he controlled from exile in Russia.

In your circles, I've heard the term metadata bounced around a bit.

Now, the only thing I know of metadata is the extra information on my cell phone camera shot.

Where it was taken, what time of day, GPS might give its location.

But presumably you have deeper relevance to that term.

What is it?

Right, one of the things that politicians use to defend these programs initially, at least some of them, because I'll point out that both your metadata and your content is being collected when it crosses the internet, for example, through what's called the upstream program.

But they've said, you know, don't worry about it in the context of telephones because nobody's listening to what you're saying on the phone.

They're simply recording who you're calling, when you're calling them, where you were or when you called them and information such as that kind of thing.

What they're talking about is data about data, metadata, sort of the context of a communication, the fact that it occurred rather than the content of it itself.

But it's deeply misleading because when we think about it in the context of mass surveillance, collecting everybody's everywhere, metadata is more valuable than content.

It's very difficult to get 330 million people to put on headphones every day and listen to 330 million phone calls.

But it's very easy to get a computer to run algorithms against the metadata the same, because metadata is very small, it's very compressible.

And you don't have to take my word for this actually.

The idea that metadata is actually more intrusive, more invasive than content is well established even amongst the defenders of mass surveillance.

Stuart Baker, the former general counsel of the National Security Agency, said that when you have enough metadata, you don't need content.

The idea here is that metadata is a proxy for content.

The director of national security, Keith Alexander, said, we kill people based on metadata.

And he's right.

When we're firing Hellfire missiles out of drones at people, we're not targeting it at individuals.

We're targeting it at cell phones because we don't know who these people are.

We don't have boots on the ground.

And that's the reason so many drone strikes go on.

But the real danger here is to assume that metadata is harmless.

We know it's used to kill people, but it also has tremendous privacy implications.

Metadata is the same thing that a private investigator collects when they follow you around all day.

They can't be close enough to you when you're sitting at a cafe to hear every word you're saying or you'll notice they're there.

But they will be close enough to you to see who you're meeting with, where you're meeting with them, how long you're there, where you go after you're done, where you live, what kind of car you drive.

All of these peripheral facts about your life, your activity, are the products of metadata surveillance.

This is called, in sort of the NSA vernacular, constructing someone's pattern of life.

And the pattern of life is derived not from the content of their communications, but from the metadata of it.

By monitoring the metadata of 330 million Americans, what you find is a perfect record of 330 million lives.

Last week, in the first part of our interview with Ed, we spoke about the battle raging between defenders of online privacy and those who would seek out our personal information.

The language of this battle is mathematics.

It's dialect cryptography.

I wanted to know how Ed Snowden, a man who was fought diligently for both the defenders and the seekers, was baptized into this battle in the first place.

This is the most technical part of our interview, and arguably the most important.

Ed is going to explain for us what encryption is all about.

Eventually I began to become fascinated by encryption technologies, anonymity, how the network of the internet fits together, how things are communicated, how they're observed.

And then as I began to work for the NSA, I also saw how they began to be subverted for sort of unintentional, or for reasons contrary to the intents of the communicants.

But when I think about the mathematics and the schemes within encryption and so on and so forth, I think about the sort of fringe topics that are less well discussed, even in the academic sector.

For example, there are ideas of encryption that are called symmetric encryption, which is where you use a password, a key that's the same on both sides, something that doesn't change.

You lock something, you've got one key that both locks it and unlocks it.

Then you have asymmetric encryption where you have one key that locks it, and then you have a separate key that unlocks it.

This allows different parties to access shared knowledge without sharing the same key, the same passwords.

But then you also have more sort of exotic esoteric methods like secret sharing, or they're called secret sharing schemes.

One of them that I think is very famous, at least in the community, is called Shamir's Secret Sharing Scheme.

This was a really challenging concept to get for someone who didn't have a formal background in mathematics, which is the idea of an n-dimensional space.

You could have a matrix of dimensions, and this is already kind of abstract and difficult for people who don't think too much about math or how to fit it into their head space.

But think about the three dimensions that we live in every day.

You've got sort of an x and a y axis if you're thinking about a regular plane, like your monitor.

You've got the horizontal space and you've got the vertical space.

But then our third dimension that we live in every day would be the z-axis, the depth.

But beyond that, when you need to start thinking about additional dimensions beyond the third, it's quite difficult for people to think about.

I would say impossible, impossible.

To try to find a fourth line that is perpendicular to the other three, I don't know anybody who can do that.

We can do it on paper, of course, mathematically.

We've got four-dimensional cubes and five-dimensional cubes.

So you're talking about an n-dimensional, n as in the, you'll determine it later.

Right, n in the context of secret sharing would be the number of parties who are sharing in the secret.

So the idea here is to enable, let's say, five people to work together to share access to one thing that's secret, but they're concerned that one person could give away the key or basically work against the interests of everyone involved.

So you have to make sure that sort of n of x participants are collaborating together to access the material before whatever is protected here, before it's released.

So you would need three of five or four of five and so on.

But how would you do this in the context of passwords and cryptography?

It's a fairly difficult problem.

But so the way they do this is through an n-dimensional array or matrix.

And the idea here is that if you think about a three-dimensional space analogous to three parties in the example, that's not so hard to get your head around.

You can think of any three-dimensional point in space, on Earth, for example, GPS coordinates or something similar to that, although that's actually two dimensions.

But you can get altitude on that.

So you get a third dimension.

Oh, there you go.

All right.

So there's your third dimension.

But you would say, all right, you have to meet at a street corner on Washington, DC or in Washington, DC.

And those are your three dimensions.

When you're at this point, sort of you have access to the secret.

But how do you impose additional constraints?

How do you get those extra N dimensions?

The fourth dimension could be time.

You would only be able to unlock this if you met on a certain street corner in Washington, DC at, you know, on February 14th of 2016.

Valentine's Day, yes.

February 14th, yes.

That's when everybody works on all their cryptography.

Then you want to add additional constraints.

How do we do this?

Similar to space time, the idea of a continuum where you don't only have physical location, but you also have an additional time constraint.

You can also impose additional requirements that substitute for dimensions.

When we think about this in the context of computer security and cryptography and things like that, you could use not only people, but what's now called multiple factors, multi-factor authentication, where instead of you simply entering a password, you have to enter a password in addition to presenting an SMS code that comes from your smart phone, a one-time use PIN code, or a physical identifier, biometric identifier.

These are additional dimensions, adding multi-dimensionality to the way that we interact with our systems and protect things mathematically.

But these are sort of the challenges to me, the hard problems in security, that are fascinating, because people, you know, we've got these brilliant academic researchers who come up with these amazing theoretical advances, but it takes a really long time for us to translate them from the university to the laboratory, to the company, to everyday life.

That time delays in almost everything that goes on in universities.

And of course, the government has been trying to speed that up to get practical, marketable products from the brainchilds of academic researchers.

So about these dimensions, let me ask you something.

If I send you an encrypted message, and that encrypted message gets intercepted, the interceptor will know, presumably, that it's an encrypted message, whether or not they can decode it.

Wouldn't it be better to send a message that they don't even know is a message at all, so that it doesn't call attention to themselves, something that is blended in the noise of the background, so that it doesn't even call attention to itself?

This is a sort of classic challenge in COVCOM, or what's called covert communications as a study, sort of a theoretical space, is how do you divorce the content of the communications, for example, whatever the messages that's protected by those encryption, by that encryption, from the fact that that communication occurred in the first place.

And this is really a challenge.

How do you send a signal that no one hears?

And when we think about this as a theoretical problem, a university problem, there are some approaches where people go, well, we can try to construct what's called a mix net, when we think about network-based communications like the internet, where we route everybody's communications into a voluntary conspiracy of volunteers around the world who are simply trying to protect people's privacy.

And when you get everybody's communications coming into one point, you then send them to a second point and a third point, and they're constantly mixed up.

So people observing the network have a much more difficult time correlating the communication ended up at the destination with where it originated from.

But beyond this, when we think about sort of a back out from the practical problems and think about the theoretical problems here, there are real questions about what happens when communications get lost in the noise.

We may not be able to hear in space, because of course in space no one can hear you scream.

But the universe is actually rich with cosmic noise, loud enough to distort messages and perhaps hide messages within them.

This may seem like an infinite source of camouflage, but it's not so simple.

Ed and I spoke about this conundrum.

And of the potential of hiding messages in the sounds of the universe.

And of course by sounds of the universe, we're referring to electromagnetic radiation, which in its own way can be noisy.

Next on StarTalk.

Welcome back to StarTalk Radio.

This is a special edition of StarTalk, where we chose to break our usual format in favor of a little one-on-one time with government whistleblower, hero, traitor, treasonous Ed Snowden.

Tonight, you are hearing part two of that interview.

In this final segment of the show, we're going back to that conversation with Ed right here in my office, when he spoke to me through a remote controlled robot, which is essentially an I-level iPad with wheels.

Through this virtual medium, he and I went back and forth about his early education, encryption technology, Fourth Amendment rights, and why he chose to break his contract of secrecy to the government, to defend the Constitution.

Let's check it out.

So the cosmic microwave background is an interesting point.

It looks like noise to, no one knows these days, but in the day when you don't even know because you only just live your billionth second, the TV's had what were called rabbit ear antennas.

Surely you've read about this in your history books.

How to adjust them on the top.

And then you couldn't move because you became part of the antenna by touching it.

But if you went between channels, there would be this sort of static on the screen, what we called static.

Some percentage of that static is the actual signal from the beginning of the universe, the Cosmic Microwave Background.

And so, but so it looks like noise locally, but in fact, if you look at it across an entire sort of spectrum of frequencies, it actually has a shape, a very distinctive shape that we know and describe highly precisely in physics.

So if you were to hide something in the Cosmic Microwave Background, you'd have to follow the shape that it takes, depending on what frequency you would communicate with.

I'm just warning you in advance if you want to hide a signal in the universe, they have a very characteristic profiles, just so you know.

So this is actually a really interesting thing that I would like to ask you about, because astronomy is pretty far from my wheelhouse.

At some level, the universe is above everyone's head.

There was an old paper that was once written on using entropy that's gathered from this cosmic microwave background radiation as a source of random numbers, because the most difficult part of generating reliable robust encryption for computer scientists and mathematicians working on cryptography today is to make a computer generate a random number, because they can't.

At the end of the day, they're deterministic machines.

They're a bunch of ones and zeros.

They're basically on and off switches.

They can't on their own do anything truly random.

Instead, they use what are called pseudo-random mathematical functions to try to develop numbers which are random enough to work for our purposes.

But all of these pseudo-random number generators rely on what's called a seed value, an initial random input, which today in computers we try to generate from, for example, the movements of someone's mouse, the time on the machines it's ticking by, network communications that are going out, things that are a little bit unpredictable or hard to guess for an adversary who's trying to attack these communications.

Well, we used to use the random number generator to generate the seed for the random number generator.

That should help a little bit, is that right?

Well, the question is how many steps of complexity can you get there that cannot be reversed?

And unfortunately, when you have adversaries of enough sophistication and budget, anything that a user who's not as powerful can do can generally be reversed by an adversary of a given level of sophistication.

But when we think about where do we get these truly random numbers from in a reliable way, they can't be guessed, it can't go back in time.

You can't figure out what the original truly random number was from which all the pseudo-random functions were run off of.

And a paper was once written on using the universe as the seed of that random function, using sort of the distant noise that comes from things like pulsars or magnetars or some other cosmological feature, and listening to that all around the world.

Because even if you could record everything that you can hear in a given location on Earth, you know, an observatory in Maui or in the state of Washington, Chile or something like that, you can't hear all of the different noise that's hitting all of the planet in every spot all of the time.

The amount that we're hearing from the universe is simply too large.

Is there any source in the universe, you can say, that would be unique in that respect or hard to observe that you think could be used as a source of truly random information?

Yeah, the problem is now we have a network of telescopes that communicate with one another that have basically all sky coverage.

Radio waves can, radio telescopes can observe the universe in the daytime and at nighttime, and these signals are typically radio signals.

So pulsars are a great example.

They're rapidly spinning.

They send pulses of radio waves.

If you wanted to nab one of those pulses and somehow index to it, in principle, you could.

But there's a finite number of pulsars that we've got them in the catalog.

You know, we've got them, they're there.

And so I'd have to think about that.

I'll dig up that paper.

Send me the paper.

I'll send you a link.

By Carrier Pigeon, so we can't trace it.

I think the NSA already has.

Yeah.

So people were thinking, could we make a GPS system that is good for all planets, that does not involve just the satellites around one planet?

And in principle, you could do that from pulsars, which are far enough away from our entire solar system that everybody can just see them, index to them, and they're the best timekeepers there ever was.

Some of them rotate thousand times a second, are called millisecond pulsars, and so they're timekeeping devices that are built into the universe.

And so we've got top people working on that one.

This brings up another thing which, to me, I've never really quite understood.

Whenever we talk about engineering of communications or electrical engineering in general, we talk about signal and noise.

And when we talk about it out in the universe, the way this is expanded, we think about it as noise, as astronomical noise.

But is it really noise?

You know, when we think about the fact that all of these different points in the universe are actually doing something, is it noise or is it signal?

I think the distinguisher we have there is whether we want it in our calculation or not.

But there's something poetic, I think, in the idea that the universe is talking to us all the time.

Yeah, that's a great way to think about it.

I once wrote an essay called Signal and Noise.

That's what it was, and I featured it in one of my books.

That was the most fun essay I've ever written, because it was a topic that the public doesn't, they're not compelled to think about much, yet it has profound implications for knowing anything at all in the universe.

And so, you're right, there are signals that I'm uninterested in because they're interfering with some other signal that I am interested in.

And so, I will repeatedly get data on the object I'm interested in to raise its signal relative to any other signal that I'm getting.

And I'll give you an example.

We have clusters of stars out there, one of the types is called a globular cluster, thousands of stars, and they're all here, and there they are, and it's a beehive.

We don't see them moving because we don't live long enough.

It's a beehive, but I'm interested in that one star right there.

How am I going to isolate that star?

What am I going to do?

And so, I focus in on it, try to get rid of as many other stars as I can.

Now, there's another star that's sitting right next to it, and it's sharing light in my detector.

There's light spillage in my detector.

I want to get rid of what I don't want and keep what I do want, and so you're right.

Many times, it is just my choice, what I'm declaring to be signal and what I'm declaring to be noise.

But there is also a fundamental source of noise.

It also exists.

In any CCD detector, you want to detect an object.

The fact that the detector is not at absolute zero means thermal currents create signal within the detector.

That's noise.

Total noise.

That's interesting because when you mention that, it raises to me the idea that by listening to something, by collecting more than we need or more than we desire, more than was relevant to us, we can basically suffer unintended consequences.

And this is very analogous, I think, to the NSA's systems of surveillance that we've seen.

And it's not just in the United States.

It's not just the NSA.

This is a global problem that every country is going to be dealing with.

The problem is mass surveillance, which is where because of all the communications that are going over the air, through cellular networks or going across the internet on fiber optic cables under the sea, we've got governments that are basically co-opting telecommunications companies or they're grabbing these fibers and they're collecting everything from them.

And just like you can get some kind of thermal input that could damage sensors or screw up your readings, we've seen the White House itself has done reviews of the value and effectiveness of mass surveillance and found that despite the fact that they're collecting or they claim the legal authority to monitor the communications of everyone in America, 330 million Americans every time they pick up the phone, it never made a concrete difference in a single terrorist investigation.

And as a result, all of the people, all of the resources that we're committing to sort of monitoring all of these innocent people's communications are taking away focus from the traditional means of law enforcement investigations and intelligence gathering that watch people who are really suspected individually of being involved in some sort of criminal activity or wrongdoing.

Basically, by creating a haystack of human lives, we're losing the needles rather than finding them.

Isn't part of why data has been collected indiscriminately, if I can say that, because if it weren't, you could accuse the authorities of profiling, which no one, that's a taboo at least in America, although it's certainly not taboo when you're boarding, certain airplanes headed certain places in the world, they'll profile you like this.

But in America, that's considered bad.

That's why they screen everyone at the airport, even the 80-year-old hunched over woman.

They screen everybody.

When we think about the problem of profiling and what not, it's the fact that they're going after too many people indiscriminately, they're trying to run everybody through an algorithm, and then they go, this doesn't work, but we don't know who we're looking for.

We want to watch everybody because they might be doing something wrong.

So let's try to narrow it down.

Let's try to select on their religion or their ethnicity, and these things are wrong because it makes criminals innocent people.

It's a criminal suspicion on people who have done nothing wrong.

But we haven't had this problem in the past when we look at investigations, and that's because rather than profiling, we have another means of investigation, which is called probable cause.

It's the idea that rather than watch people who we don't know are involved in any wrongdoing, we don't watch people who haven't done anything wrong.

We watch people who specifically are doing something wrong, who we have some evidence to indicate that they're doing something nefarious or contrary to our laws, and we monitor them specific.

The distinction between mass surveillance, which we know doesn't work, and targeted surveillance in this regard, is the idea that rather than simply collect the communications of everybody in America at the telephone companies or at the internet service providers, you do the traditional means of investigation, which are to tap their phones specifically, whether that's at their house, whether that's through their computer, whether that's through their cell phone, and on this basis, you don't have to worry about profiling, you don't have to worry about anything else.

If you're thinking about profiling, what you're really arguing for, the idea that sort of we would need to watch everybody, because we don't know who's doing something wrong specifically, what you're arguing for is a paradigm shift in the method of investigation, which would be pre-criminal investigation.

Instead of investigating people who have broken the law and then holding them to the account of justice, you want to investigate everybody all the time in case they might do something wrong, regardless of whether or not they actually have.

Isn't that what happens at airport security lines?

That is what happens at airport security lines, but there's a distinction.

The intrusion there is very narrow, because you only have a limited amount of effects on you.

You've got the clothes you're wearing, you've got the things in your bag.

They can't read your thoughts, they can't ask about your family, they don't know what your hopes and dreams are, things like that.

You're in Moscow.

Why didn't you choose a tropical country with palm trees and sipping coconut on the beach right now?

Good question.

I actually never intended to end up in Russia.

I was originally booked.

There were journalists who were taking pictures of my plane seat at the part of Russia without me, to go to Ecuador or Bolivia or Uruguay or Venezuela, something like that.

Some places, it was a little bit warmer.

But unfortunately, the Department of State canceled my passport when I was flying on my way there, and they trapped me in the airport in Russia.

But, you know, I will say that despite all of the things that I've lost, I'm glad that I was able to play at least a small part in doing something I can be proud of.

You've been listening to Star Talk Radio and my one-on-one conversation with government whistleblower Ed Snowden.

Hope you were able to glean something new from these past two shows.

Whether your ideas about Ed were reinforced or you were lifted into a different way of thinking about the situation.

Or maybe you just learned something new about encryption technology.

And welcome Ed as a member of the geek community, in the way, of course, I have done.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist, and as always I bid you to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron