Join Neil deGrasse Tyson and comic co-host Leighann Lord as they explore the dark mysteries of our cosmos, from the infinitesimal electron to the higher dimensions of the multiverse. You’ll find out whether photons have mass, why the Moon doesn’t really orbit the Earth, and how many stars are born each day in our galaxy’s stellar nurseries. Neil explains how neutron stars could become black holes and why space is anything but dark, ablaze in microwaves and other energy beyond visible light. At times, the science borders on the philosophical, as when Neil proclaims, “We are the singularity writ large across the dimensions of the cosmos.” But there’s plenty of physics, too, as your own personal astrophysicist answers Cosmic Queries about the speed of gravity, the difference between “aether” and the Higgs field, what dark flow has to do with galactic expansion, and how long we have until we crash into the Andromeda galaxy.

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Now. This is StarTalk Radio. I'm your host, astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson. And this is Cosmic Queries. Keep thinking of it as...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Now.

This is StarTalk Radio.

I'm your host, astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

And this is Cosmic Queries.

Keep thinking of it as an after hours kind of thing.

It has that feel to it.

That is the voice of Leighann Lord.

Leighann, thanks for being on StarTalk again.

Oh, thank you for having me back.

You know I love it here.

Oh, excellent, plus you're a geek person.

Totally geek, so you can do this.

And in our Cosmic Queries editions, we get one of our favorite comedians, in this case it's you.

Thank you.

To cull the internet on our websites and all our social media to collect questions.

Sometimes solicited, others, the questions just come in.

They do.

Because people are bubbling with curiosity.

Right, and you know, to have a personal astrophysicist.

Why would you not take advantage of that?

Sure, so let's go ahead and do that.

I haven't seen these questions before.

Right.

Not to stump me or anything, but just, my answers are fresh and if I don't know something, I'll tell you.

Go for it.

Alrighty.

The topic is dark things, right?

We're exploring the dark mysteries of the universe here.

Mystery, mysteries or dark mysteries?

Dark mysteries.

With quotes.

Dark mysteries, let's go for it.

All right, well, this first question, we're coming in from Nick Fisher, and he wants to know if all this light is created in the universe and travels for billions of years, why is it still so dark?

Ooh.

Yeah.

Good question.

Well, a couple of things.

There's light from stars that comes for billions of years across the universe, and when you look at that light, you see the star, so it's not dark.

It's dimmer, but it's not dark, and light comes from the billions of stars of galaxies, the billions of stars contained within a galaxy, you look to the edge of the universe, there's a galaxy there, so it's not dark.

So galaxies and stars and things, they are themselves not dark, all right?

So they get dimmer, but they're not dark.

Now, how about the rest of what is dark?

Yes.

It's not dark.

It's not.

It is ablaze in microwave light.

Does that mean it's blazing, but we can't see it?

Your eyes can't see microwaves.

Yeah, if your eyes can see.

No matter what prescription I put in.

Exactly right.

So the whole spectrum of light is not just Roy G.

Biv, which is?

Roy G.

Biv, the colors red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet.

Excellent.

Indigo is the tricky one that people never get.

Who doesn't get indigo?

Isaac Newton first labeled those colors and that's a visible light.

And for the longest time, we thought that that was the only way that light could exist.

And if we're looking out in the universe, that's the only way that the universe would speak to us.

Until we learn that below red, we have infrared and above violet, we have ultraviolet.

And the light goes in each direction.

So your eyes are not the measure of all that can be seen in the universe.

And the methods and tools of the astrophysicist over the past century, we have found ways to detect light far outside of visible light.

And that includes radio waves and gamma rays and x-rays and microwaves.

And the universe is ablaze in microwave light.

Wow, we just can't see it with the eyes we have.

If you were Geordie, you could.

Geordie LaForge with the banana clip visor.

That visor enables him on Star Trek Next Generation.

Next Gen, of course.

To see all the spectrum of light that even the human eye can't see.

And he would look up, tune in, and say the universe is aglow.

You know, that actually brings up an issue.

He possibly unfairly then got his job because he can see stuff that other people could not.

You mean Geordie on the show?

On the show, not the actor.

The actor, Kuntukinte, the actor.

The actor, Kuntukinte.

Did you seriously go back to roots?

I so did.

Why don't you throw a little reading rainbow in there?

We'll just give his whole resume, why don't we?

We met, we have a StarTalk episode.

Yeah, I know.

I bumped into them, I mean, we arranged an interview at Comic-Con 2012.

Brent Spiner, yes.

And Brent Spiner was there too, Data.

So jealous.

Yeah, we were told together, we had him together.

That's one of my favorite photos.

The space-time continuum almost imploded there.

So, what else you got?

All right, I have a question from Joe Vera.

And he says, I recently found out about something called Dark Flow.

Isn't that a DJ?

Okay, I'm sorry.

Yeah, exactly.

A beat-boxing DJ, Dark Flow.

That's a great name.

It is, isn't it?

It sounds like a cartoon.

All right, now from what I gather, it is the only-

The other great name for it was like MC Squared.

That's it, you know, if you wanna be MC.

I'm gonna pretend I didn't hear that.

All right, be there or be a four-sided polygon.

Can we get any geekier?

All right.

Got you, go on.

All right, from what I gather-

But four-sided polygons are not always square.

They could be-

Arombus.

Arombus, which is my favorite.

Love Arombus.

We're never getting to this question.

I know, go, sorry.

Okay, all right, so recently found out about something called dark flow.

On this show, you're allowed to get your geek on.

If you can't do that here-

If you can't geek out here.

Where?

Excuse me, all right, go on.

All right, from what I gather, it is the unexplained coherent motion of galaxies toward one side of the universe.

Can you please elaborate on this phenomenon and its possible ramifications for our understanding of the universe?

Yeah, there's something called the great attractor, got labeled that because when you-

When you measure the speed of galaxies as they move in the universe, there are multiple ways to do this.

One of them is just how fast is the universe expanding?

So that's the speed they have just from the expanding universe.

But while that's happening, galaxies are moving among themselves.

For example, we are about to, in seven billion years or so, about to collide with the Andromeda Galaxy.

It's our nearest big galaxy.

So we're about to collide, but the greater activity of the universe is expansion while galaxies are still moving among themselves.

So when you map the speeds of all these galaxies, it was found that there's a whole swath of galaxies in the universe that have sort of an extra motion towards one direction.

So you don't know if they're escaping something or being drawn towards something.

Run, everybody.

So it's an interesting sort of phenomenon that's not completely explained.

So you just didn't explain it.

That's true.

I love it.

You made it sound real good, though.

That's nice, wow.

If somebody figured it out recently, I haven't read about it.

Let's put it that way.

Well, check your Twitter stream.

I'll check it, yes.

All right, that's hilarious.

All right, next question is from John Coleman, and he says, is there any possibility that the singularity that created our universe is still active and part of the reason the universe is expanding?

Oh, no, the singularity was a point in space and time.

Oh.

It is not still around.

We are the singularity writ large across the dimensions of the cosmos.

I'm gonna put that on a T-shirt.

I'm a singularity, what are you?

No, you were once a singularity.

I was once a singularity.

We are what the singularity became.

I'm a has-been.

So is it good for you?

It's good for me.

We have like 15 seconds left.

See what you can give me in 15 seconds.

All right.

Kevin Pulido wants to know, according to the theory of the multiverse, what is space, call it space, between universes?

No, 15 seconds is not enough time to answer that question.

So when we come back on StarTalk Radio, the Cosmic Queries edition, more of the questions, your questions, culled from the internet, from our Facebook page, like us on Facebook.

And of course, you can put your questions online at startalkradio.net.

This is StarTalk, the Cosmic Queries edition, which I like to think of as StarTalk after hours.

Leighann Lord, thanks for being with me.

Oh, always, thank you.

And you tweet at Leighann Lord.

But you spell your name funny.

I do, my parents spelled my name funny.

You could change it, L-E-I-G-H-A-N-N, Leighann Lord.

That's your Twitter handle, and I know where you're performing, cause I'm on your list at veryfunnylady.com.

Yes, you can spell that, that's easy.

So, you've got questions.

I haven't seen these questions before, and they're all that is mysterious and dark in the universe.

Yes, yes.

Now, we left off, there's one, read me that question again.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, cause I thought it was a good question, and this is from Kevin Polito again, and he said, according to the theory of multiverse, what is space, and he says, I'll call it space, between universes?

What is the space between universes?

Yeah, it's a higher dimension.

Next question.

Oh, and not the fifth dimension, as in the singing group.

Right, actually, there's a fifth dimension in there somewhere, but if you take the three dimensionality of our universe, and then you embed it among other universes in another kind of space, that's a higher dimension.

And in fact, I hosted a panel on nothing.

You hosted a panel on Seinfeld?

On nothing at my host institution, the American Museum of Natural History, and we talked about what is between galaxies if the multiverse produces galaxies.

And that's a kind of nothing, but it turns out it's not the best nothing that you can come up with.

It's like the dark alleys of the universe?

No, because that still has dimensions.

Is it nothing if nothing's there, but it still has a dimensionality?

See, we got really deep.

I mean, heads were exploding left and right in the aisle.

Like now.

So, no, it's what we would call the space of a higher dimension, which is not even our space.

Because it would not have the matter, it would not have the energy, it would not have anything that we associated with our stuff or even with where our stuff isn't.

Because outside of our universe, there's not even the nothing of space.

Well, because if space is nothing, then where there is no space, there's not even that nothing.

Okay, next question.

I'm sorry, I'm not allowed to call the next question.

Go for it, go for it.

Because I'm just, what?

Go for it.

I need to go back to school.

Okay, Edwin Martina.

There's nothing wrong with you because you can't imagine higher dimensions than the ones in which we are embedded.

I imagine higher dimensions, but.

No, here's the way, I'll help you out.

I'll hook you up, ready?

All right, so take an ant and put them on a piece of paper and then draw a box around the ant with a Sharpie, and say, ant, you can't leave the page.

Oh, that's not gonna work.

All right, and so you just tell that to the ant, and the ant says, okay.

And so the ant walks around, it hits this line that you drew, and it can't get past it.

And it's a prisoner in your sheet of paper surrounded by this square drawn by your Sharpie, because the ant is embedded as part of the two-dimensional world you just created for it.

And you can say, well, just escape.

I can't escape.

Just jump out of the page, step over the line and then go back into the page.

And the ant says, I don't know what out of the page means.

This is my universe.

So now I put you in prison, surrounded not by a square that was containing the ant, I surround you by a cube, six walls.

And you say, I can't get out.

But from a higher dimension, that person say, just step out into the higher dimension, step back in and you've escaped.

And you say, I have no idea what you're talking.

No, no, I actually do.

And I'm totally getting, I mean, I'm imagining, that's why the pictures move in Hogwarts, because they can step out of their dimension.

You step out of your dimension and then the walls no longer contain you.

Yeah, so you step out of our dimension, you get to see things you would not otherwise have even known were there, perhaps even the multiverse itself.

Next question, Leighann.

I'd love, I just want to bask in that, but I'll move on.

Basking doesn't work on radio?

No, it doesn't, that's why I'm moving on.

Edwin Martinez wants to know, why is energy considered different from mass?

And how is it that photons or waves are able to travel but yet have no defined mass?

Should not something have a mass if it's ejected and has a defined speed?

Yeah, so photons have a mass equivalent.

Okay.

You plug their energy into which equation?

Exactly, so if there's energy on one side.

And a C squared is the speed of light squared.

So you take that, remember your algebra, bring that to the left side.

You divide both sides by C squared.

So you have E over C squared equals M.

All right, if you remember your algebra, that's like learn that in fourth grade.

I'm rolling.

All right, so.

Well, maybe in your school.

I didn't get mine until sixth grade, but you know, whatever.

So you got that, and so you plug in the energy, you divide by C squared.

That will tell you how much mass equivalent that energy has.

And once you have the mass, you can plug that into a gravity equation, and that will tell you how much gravity the energy has.

And so they work back and forth with one another.

The difference is, once you become energy, if you're electromagnetic energy, like light, then you move at the speed of light.

I mean, you move at very high speeds, at the speed of light.

If you have material substance, you cannot move at that speed.

That's the problem.

So what would you rather be, light energy or mass energy or mass?

Light energy, good duh.

That's easy.

That's easy.

Oh, finally, a question I can answer.

Moving on.

I have a question.

Oh, by the way.

Yes, by the way.

As you move faster, time slows down for you.

Well, yeah.

Yeah.

See, when I actually know something, I have to revel in it.

So Einstein's relativity, when you speed up, your time slows down relative to others who are watching you.

And the closer you get to the speed of light, the slower time moves for you.

At the speed of light, time stops.

Which means photons of light do not move forward in time.

They live forever because they have no clock.

Because they're moving at the speed of light?

Correct.

Did I just say that?

Next question.

So does this have any reason why on Star Trek, the Enterprise's photon torpedoes don't work?

Or these are different photons?

No, here's the problem with the photon torpedo.

If it's the energy going forward, you wouldn't see it from the side.

That's just an FYI.

Yeah, okay.

It's empty space.

It's just the energy's not coming to you, the viewer.

It's going to the target.

Right.

So the photon torpedo should be invisible to anyone who is not getting hit by the photon torpedo.

Of course.

Yeah, otherwise you're wasting the energy illuminating my sight line for energy you're trying to deposit in the target.

And the entire special effects department just got fired.

It's the same with the phasers.

If it's directed energy, you don't want energy leaking out the side of it.

Right.

Unless there's like someone hit two chalkboard erasers together along the path between the enterprise and the target, and then it would illuminate the chalk dust.

Along the way.

Wow, that's very imaginative.

All right, I have another question.

I have a question from Natalie Dangle.

Approximately how many stars are born and die each day?

Oh, I'd love that.

Now what's a day?

How are we defining a day?

I'm assuming Earth Day.

Let's assume.

Not somebody else's day, Earth.

Earth.

Right.

But of course, other planets have days, yes.

In fact, Venus' day is longer than its year.

Just chill on that one for a bit.

So, Leighann's face just scrunched up in a, like.

Because I'm chewing on it.

I'm actually chewing on it, that's okay.

Yeah, on Venus, the day lasts longer than a year, but we'll get back to that.

If we go there.

So, now where was I before I distracted myself?

How many stars were born each day?

How many stars were born each day?

So, you can do what's called a back of the envelope calculation.

You ready?

Our galaxy has about, let's just say 100 billion stars.

And the universe has been around for about 10 billion years.

Back of the envelope means you change the number to make the math easy.

But your answer will be.

I back of the envelope my taxes all the time.

So, but your answer will be approximately correct.

And later on, you could put the exact number in if you want the exact answer.

Fine tune.

So say we have about 100 billion stars and the universe and the galaxy has been around for 10 billion years.

Okay?

So, we have 100 billion stars and we've been around for 10 billion years.

That means the galaxy makes 10 stars a year.

That's an average.

Yeah, on average.

That's right.

If it made 10 stars a year throughout its whole life, we'd have 100 billion stars over the 10 billion years.

That's how that works.

So it makes about 10 stars a year.

So that's about one a month.

And so we don't quite make a star a day on average, about one a month.

We could live with that.

However, that's not actually how stars are born.

They're born episodically in stars, in stellar nurseries where thousands of stars are born all at the same time.

So if you were a planet in orbit around one of those stars, you'll see stars lighting up daily as they are born.

That must be pretty.

Well, not daily, but frequently.

Like, poof, there's Brad Pitt.

Woof, there's Angelina Jolie.

A reminder that we had the stars first before there were Hollywood stars.

Oh, well, of course, of course.

We got like half a minute left.

What do you got?

What can we fit in here in this segment?

Wow, okay, I'll try.

This is from Abdele.

I can't even get the name out that quick.

All right, here's a simple question.

The moon orbits the earth, the earth orbits the sun, our solar system orbits the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

Does this pattern stop on a galaxy level or is our galaxy orbiting something else?

And that's from Chris Carlson.

Cool question.

I can do that in five seconds.

Listening.

Four, three, no, I can't do it.

Dang.

I'm gonna come back.

What does our galaxy orbit when we come back to StarTalk Radio, the Cosmic Queries edition.

This is StarTalk Cosmic Queries.

I'm your host, astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson.

If you never knew it, my day job is as director of the Hayden Planetarium here at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Come by and visit, tell the front gate that you know me, and they'll still charge you admission.

Just an FYI.

So, Leighann Lord, I got you in studio.

Thanks for reading Cosmic Queries to me.

Oh, no, thank you.

And these are dark things in the universe, dark mysteries of the cosmos.

Dark mysteries of the cosmos.

And we just didn't have time in that last segment.

What was that last question?

All right, that last question, again, was from Chris Carlson.

And basically, the moon orbits the earth, the earth orbits the sun, and our solar system orbits the center of the Milky Way.

So, does this pattern stop on a galaxy level, or is our galaxy, among others, orbiting something else?

We technically are orbiting the Andromeda Galaxy.

Oh, by the way, we should be clear.

The moon doesn't orbit the earth.

They, the moon doesn't orbit the earth.

The moon and earth orbit a common center of gravity.

Yes.

Which is not in the center of the earth.

In fact, it's 1,000 miles below earth's surface on a line between the center of the earth and the moon, wherever the moon is at any time.

But we're 4,000 miles in radius.

So 1,000 miles down is not the center of the earth.

So while the moon goes around us, we do a kind of a jig.

We do a little jiggle, all right?

The earth shimmy, the earth Harlem shake.

The earth kind of shimmies because the point that it revolves is within itself and it's not at its center.

So you got that, all right?

Meanwhile, earth and the moon go around the sun, a common center of mass between the two of them, which is not at the center of the sun.

I'm sensing a pattern here.

Except we are so schmaltzy compared to the sun that the center of mass between the sun and the earth is really close to the center of the sun.

The sun is so large, a million earths can fit inside it.

So we're not really yanking the sun's chains here.

But the little bit that we do, that's how many planets are discovered orbiting other stars.

You look at a star and the star's not just hanging out, it is shimmying.

And you're saying we infer a source of gravity that's orbiting that shimmying star.

And the amount it shimmies tells you how far away the planet is from it and how much mass it contains.

So, yeah, so earth and moon, common center of gravity, earth, moon and the sun, common center of gravity, the sun and the center of the galaxy, we orbit that.

The galaxy is technically in orbit with the Andromeda galaxy together, except our orbits are really elongated.

They're not circular, they're so elongated that in fact we're on a collision course.

Really?

Yes, we will collide with Andromeda in about seven billion years.

All right, I'll re-mark my calendar.

It will be a train wreck, a titanic collision.

Mark, put it in your smartphone, you'll have it.

All right, shall we move on?

Yes.

All right, this is from Lexi Davis.

This is a cute question, I love this.

Is there anything smaller than the infinitely small and can you put it in a way that does not make me hate that I don't even get to be in pre-calc till next year?

Ooh, high school student, nice.

Can you smell that?

Young person.

Yeah, so by the way, see if you really like math, see if you can skip pre-calc and just go straight to calc.

Just tell them Tyson told you.

I have a note from my personal astrophysicist.

Can I please get in?

And just go, see if you can go straight to calc.

But, all right, so is there anything smaller than infinitesimally small?

Yes.

You are so evil.

Okay, no, no, so here it is.

The electron is smaller than the smallest thing we have ever measured.

And in fact, it is so small, we do not know how small it is.

We cannot measure it.

It is so small.

In fact, it could be so small as to not occupy any volume at all.

As far as our measurement devices are concerned, it has no dimensions at all.

The electron.

So, the electron comes closest to infinitesimally small of anything we have ever known, thought of, dreamt of or measured.

Okay, so.

Yeah, so.

Got it.

There you go.

What else you got?

I have a question from Paul Lundgren.

And he says, can a brown dwarf, wait, do I, no, okay, I'm moving on.

Can a brown dwarf accumulate enough matter?

I'm not, yeah, I thought about it and I like my job.

Can a brown dwarf accumulate enough matter to ignite itself into a star?

And then he says, corollary, can a neutron star gather enough additional mass to collapse into a black hole?

Well, did that person actually use the word corollary?

Corollary, sir.

Corollary, very nice.

That is our SAT word of the day from Paul Lundgren.

So a brown dwarf is a failed star, didn't have enough mass to make its center hot enough.

It's a muggle?

Sorry.

So the center never got hot enough to engage nuclear fusion.

And so it kind of withers there, giving up the little bit of heat it did accumulate on collapse, I know.

So they're asking if you sort of fed it matter, could you ignite the center and turn it into a star?

Yes, and that would be awesome.

If we had the power over stars, you can turn off some stars, turn on other stars.

And in fact, you could do that with Jupiter.

Jupiter is about one-tenth, a little less than one-tenth the mass necessary for a star.

If you start feeding it material, that puppy will grow, get hot in the middle, bam, we'll have a two-star solar system.

Wow.

Oh yeah, that would be good.

And the other one was about the neutron star.

We'll get back to the neutron star after this break.

Oh great.

Can we do something with the neutron star by adding matter to it?

We'll see in a moment.

We're back, StarTalk Radio, After Hours.

Cosmic Queries edition, Leighann Lord, thanks for being with me.

Thank you.

Excellent, so we're reading Dark Mysteries of the Universe.

Yes.

Questions I haven't seen.

You have not seen me.

Hearing them for the first time.

And at the break, we had an awesome question from a high schooler.

Well, that was from Lexi.

I don't know if Paul is in high school or.

Oh, okay, great, but we answered Lexi's question.

We did answer Lexi's question, and you did.

Well, I'm assuming she's in high school because she was talking about taking pre-calc.

Pre-calc, right.

Right, and you wouldn't really do that in elementary school, and you could be like a full-up adult going back to school.

You could be.

You could be, but I bet she's like in 10th grade or something like that.

Right, and you're advising straight to calculus.

If you love it, just.

Just fight for the big dog.

No delay, yeah, don't know this pre stuff.

That's like preschool, just go straight to school.

Straight to school.

Directly to school, do not fast go.

The pre-nup, just go straight to the nup.

Wow, no, no, no, he don't mean that, y'all.

Get a pre-nup.

Don't mess around, get a pre-nup.

All right, well, it was Paul Lundgren who had a two-part question, and he wants to know if we could gather, could a neutron star gather enough additional mass to collapse into a black hole?

Yes.

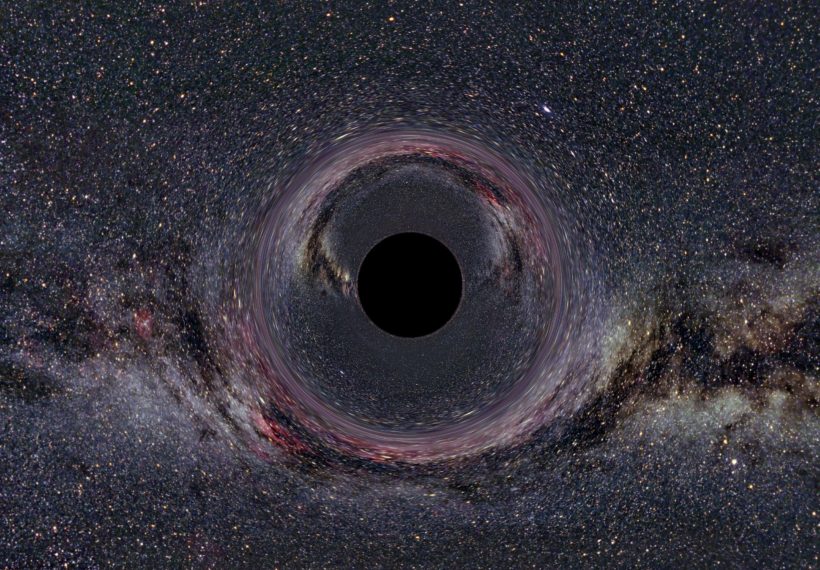

So a neutron star is below the mass, it's the endpoint of a star's death, a high mass star's death, and it didn't have enough mass.

I say high mass, but it's not high enough to cram the material down in the middle to create a black hole beyond, a boundary beyond which the matter will never be seen again.

So here's the problem.

We think that if you just slowly deposit mass onto a neutron star, it will flare up.

It might flare up rather than become a black hole.

So you have to add it in a way that the whole thing knows about all the mass at the same time, right?

So that might be hard to do.

In other words, it's not clear whether you can just feed it until it tipped its threshold.

You might have to add it all at once.

I'd have to check my equations on that, but that's my guess.

Okay, because we don't know the tipping point?

Yeah, because you just put on a little bit at a time, that might flare up on its own and then it's gone.

It blows itself away.

Yeah, that's how the original stuff left.

The original star that exploded and left behind the neutron star blew up.

That's what happened.

So I think you'd have to need a scheme to add it all at once.

Hmm, okay, as with everything else, I'm taking your word for it.

Oh, by the way, the neutron star is really dense.

I mean, it's-

It's not smart.

So it's, yeah, no, dense, heavy, dense.

And I tweeted, because I swear in the movie Thor, the guy said that Thor's hammer was forged of the material of a dying star.

And I said, cool, I can calculate how heavy the hammer must be, so-

Only you would sit there in the theater and say that.

No, no, I said, I can so do this.

And so, but I didn't know the dimensions of the hammer.

And so a friend of mine got me a Thor's hammer to borrow, that would have to give it back in the morning.

You've got Thor's hammer.

And so I measured it up and I said, okay, well, this is pretty awesome.

And I forgot the number I got.

It was something like the hammer, if you crammed a herd of 60 billion elephants into the volume of that hammer, it would weigh about the same as the hammer.

And so that's why the Hulk couldn't lift it.

And I was, so I tweeted that.

I showed a picture of me holding the hammer.

And then someone geekier than I am, a professor of physics-

Does this person exist?

Who's a Thor enthusiast, said, no, it's not forged of neutron star matter.

It's not forged of the material of a dying star.

It's forged in the material of a dying star, but it's made of some other stuff that is in fact as light as feathers.

So I said, well, that's no fun.

The hammer weighs as much as feathers, and then therefore it's really the magic god power that prevents you from lifting it or enables you to lift it.

So I thought that was nowhere near as interesting as my elephants.

No, no, not at all.

It all turns on an article.

But I will in and of, but I'll defer.

I mean, you gotta defer to the folks who live for this stuff.

So go on, that's my aside on the neutron star, but go on.

That is amazing.

You know what, you still had me at the fact that somebody got you the hammer.

This is totally not legal.

It's so cool.

It's got the leather strap and everything.

Oh yeah.

Very sexy.

All right, I have more questions.

From George Beardston, how does the Higgs feel different from earlier ideas of an ether?

Oh, did you spell ether right?

A-E?

Yes, yes.

The A is silent.

A is silent, so it's a diphthong.

It's a diphthong.

Yeah, I think it's a diphthong.

That's very kinky.

They should invent a new bathing suit, the diphthong, you know?

That would be cool.

So let me see, we only have like 20 seconds left.

Yeah, cause you're fooling around.

Let me see, well, I have to give half the answer and you gotta get the full answer at the end of the break.

But the ether was this proposed medium of the cosmos through which light traveled.

Because people knew that light was a wave and sound is a wave and sound doesn't move through a vacuum, does it?

Do you ever remember the bell jar experiment where you have a bell ringing, you put a jar over it, you evacuate all the air and the bell shuts off, the bell is ringing and you can't hear it.

It doesn't go through a vacuum, so neither should light was the hypothesis.

When we come back, more on the answer to that question on StarTalk.

StarTalk, Cosmic Queries.

This is the last segment.

It is.

This goes by way too fast.

And this is normally our lightning round, and it will be, but I left a question hanging out there.

So the ether, it was about, is the Higgs field like the ether of yesteryear, perhaps?

Was that how that question went?

Well, yeah, how does the Higgs field differ from earlier ideas of the ether?

Yeah, because the ether was a thing, nobody knew what it was, that was proposed to allow light to vibrate its way from a star to us through the vacuum of space.

Because sound needs something to vibrate, the ground, the air, sound doesn't travel through space, such was the tagline to the movie Alien in space, no one can hear you scream.

No one can hear you scream, yes.

However, light travels through it, so surely there must have been a medium out there through which light can move and vibrate, and it was supposed to be the ether, but it was never found, never measured, it was never found, and it went away.

So is the ether dark matter?

No, we learned that light does not require any medium at all to vibrate, it is self-vibrating.

Oh, man.

That actually physically hurt.

I'm just talking universe here.

To strain myself.

I'm just universe here.

So this is the lightning round.

Lightning round, Cosmic Race, let me get my bell.

See, we'll check it.

There we go.

All right.

So let's see how many questions we can get through in this final go.

All right, you ready?

Yes.

Mike Thorson, what is the speed of gravity?

Speed of gravity is the same as the speed of light, 186,282 miles per second.

Nice.

Jesus Perez.

Sorry, that's the speed of a change of gravity.

If you jiggle the space-time continuum, that ripple will move at the speed of light.

Jiggling the space, listen.

Jesus Perez, how do you know math is like?

Jesus Perez.

Oh, you can say Jesus.

Oh, well, Jesus reads our webpages.

Of course he does.

Jesus is literate.

How do you know math is the language of the universe?

How do we know?

Because the universe tells us.

Eugene Wigner, a physicist back in the 20th century, commented on the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics.

The unreasonable effectiveness.

Because we invented it, yet it accounts for the operations and motions of the universe.

Since math is purely logical, it means the universe at its finest is logical.

The math is Vulcan, love it.

Lionel Lyman wants to know, can you explain zero point space?

Oh yeah, so the vacuum of space is not actually empty.

It's not.

No, there is, because of quantum physics, every spot in that vacuum has a certain chance of having energy associated with it.

Non-zero energy and particles pop in and out of existence there, and it's called the zero point energy.

And space enthusiasts, science fiction enthusiasts want to one day tap that energy and drive spaceships through the vacuum of space without having to go back and refuel, but I think that's unlikely.

Because you can't access it, it's not accessible energy to you.

But that's zero point energy, that's what that is.

Kirk Wilkinson wants to know if there's-

Wait, wait, wait, no, sorry, sorry, that's vacuum energy.

Undo, can we undo the bell?

Undo the bell, undo the bell.

I haven't seen these questions before.

That's vacuum energy, that's the energy of the vacuum.

Zero point energy is if you chill something to zero degrees, where there's no energy left in it, there's still energy left in it.

Right, because something has a temperature.

How is that not a contradiction?

Something has temperature because its molecules vibrate.

Lower the temperature, they vibrate less.

Lower it more, they vibrate even less.

Classically, if you took that temperature to zero, absolute zero it's called, they wouldn't vibrate at all.

All motion would stop, but quantum physics tells us they can't stop, they can never stop, and that is zero point energy.

Next.

Nice, Kirk Wilkinson.

If there's a super massive black hole at the center of our galaxy, could the entire galaxy then be considered an accretion disk?

Ooh, no, because we are not accreting to the black hole.

Thankfully, there's a gap between us and that black hole that is big enough, it ain't getting us.

We gonna shift a little bit to Star Wars.

Which means it's possible to be far enough away from, it's possible to be far enough away from a black hole and never get sucked in at all.

Nice, good to know.

I'll keep my distance.

Adam Young wants to know, have we considered the consequences of tapping into the dark side of the force?

And is the dark side of the force really stronger or just more lucid?

Ooh, well, all the forces we know don't have dark sides.

You haven't met my mother.

So yeah, there's a push-pull, there's an uptick.

There are forces that can move and shrink and things, but we don't put emotional cultural interpretations upon them.

They're just forces.

Nice, all right.

This is an email from, I can't see what it's from.

Oh, it's from Paul Leonard.

Oh, by the way, if we did, then you'd know they would have to be evil, otherwise you could not define any force as good.

Good.

This is another show.

All right, if every action, this is from Paul Leonard, if every action or decision can spawn an alternate universe, where does this universe worth of matter and energy come from?

And this guy's been losing sleep over this.

It has been hypothesized that at every point you can choose to make something happen, you choose to do so, but another universe spawns that continues the way you would have existed in that other way.

This is the multi-universe hypothesis of quantum physics.

Sliding doors, got it.

Yeah, yeah.

And so that was a way to understand how an experiment can have multiple simultaneous outcomes.

Yes.

Maybe the universe split, but no one takes that literally seriously.

It's just a way to explain stuff that we have no clue what it is that's actually doing.

That's why quantum mechanics remains seriously mysterious, even to experts.

That is all the time we have for Cosmic Queries.

Leighann, thanks for being on the show.

Brought to you in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

You've been listening to StarTalk Radio.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, telling you, as always, to keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron