The brain’s 100 billion neurons speak to each other by chemical and electrical signaling, and this complicated communication provides us with everything we know and defines who we are. But when it is led astray, we can end up with false memories, hallucinations, and many other misunderstandings of the world around us. Learn about the role of the hippocampus in memory, the effects of LSD on the brain, the possible medical uses of LSD and other psychotropic drugs, and what a 19th century railroad worker named Phineas Gage can teach us about traumatic brain injuries.

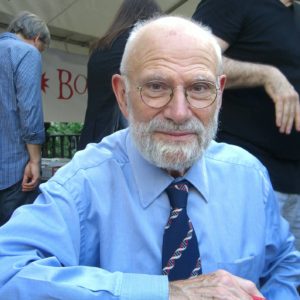

Oliver Sacks, author of best-selling books on brain disorders, including “Awakenings” which was made into an Oscar-nominated film, discusses some strange cerebral shenanigans that can shape our senses. Neil is also joined by Cara Santa Maria, a science educator with a background in neuroscience, and the comedian Chuck Nice, whose mother used to tell him that “he ain’t right in the head”

Transcript

DOWNLOAD SRT

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide. StarTalk begins right now. Welcome back to StarTalk, I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist. This week, we're talking about the brain. And I had to...

Welcome to StarTalk, your place in the universe where science and pop culture collide.

StarTalk begins right now.

Welcome back to StarTalk, I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson, your personal astrophysicist.

This week, we're talking about the brain.

And I had to bring in Chuck Nice for that.

Chuck, welcome back to StarTalk.

Hey Neil, what's happening?

Can't get enough of you, man.

Hey, I don't blame you, man.

We brought you in for the Super Bowl show and for the brain show.

What's that?

Actually two of my favorite things in the world.

I find the brain to be one of the most fascinating studies that anyone can undertake.

That in football, the brain gets bashed in football.

So they totally hooked up for that.

So it's about the brain, because the brain is everything, right?

I think so, yeah.

We try to define what separates us from other animals.

Right.

And it's language, it's abstract reasoning.

We do art and philosophy and music and science and-

Science.

And so we try to sort of say that we are apart from the animals because our brain can accomplish all that.

Actually, I think some other animals are doing calculus on the side.

You think so?

What animal would be able to do calculus?

If you could pick one.

If I could pick one, dolphins.

Dolphins probably.

Give them a pen.

If they could ever use it, they would show us what's really going on.

One of my favorite memories is of one of the Gary Larson comic, where they farm animals, and they're just talking to each other.

The farmer is not there.

The chicken is talking to the horse, is talking to the cow, and the chicken says, but if you take the mass and divide it by the square root of the speed of light, then you get the same answer.

Right.

And the horse answers, but you're missing the basic premise of my theory.

And then someone else says, farmer, cluck, cluck, cluck, move.

So for all we know, this is what's really going on.

But you know, neither you nor I are an expert on the brain, and we had to reach out into the ether and find who could help us do this.

And so we found, we found Kara Santamaria.

Kara, welcome to StarTalk Radio.

Yeah.

So you're an expert on the brain and brain function, and you've taught it before.

Did we call you a neuroscience educator?

What's the best title we can use for you?

Well, I've taught in psychology and biology.

I guess you could call me an educator, student of the neurosciences.

So aren't we all?

Because who knows it all?

Nobody knows it all.

So everybody's a student, even those who say they're not.

That's true.

Or who profess to say they know it all.

That's true.

They don't know Jack.

No.

You never really feel like you know much.

I think when you're studying these things, you always kind of look back on what you've accomplished and say, really, am I just a hack here?

How much of this did I really gather?

There's so much more.

Well, there's the stuff to actually learn that we know, and then there's the stuff beyond that that no one has even figured out yet.

Exactly.

There's a lot of that in neuroscience.

And astrophysics.

I think those are two very big frontiers.

They are.

One is the inner and one is the outer space.

Yes, indeed.

And so what I wondered, so you taught where in New York, if I remember correctly, from your resume.

I was in New York for about a year.

And before that, I was in Texas for many years.

In Texas.

And what do you call home?

Now I'm in LA.

In LA?

Yeah, I'm in LA.

No, no, I mean, where are your roots?

My roots are in Texas.

I'm definitely a Texas girl.

Transplant.

Okay.

Well, welcome to StarTalk Radio.

We're going to be picking your brain and try to leave you with some left to do your work.

As the non-scientists in the room, may I point out to our listeners two things.

One, Kara is hot as hell.

That's number one.

Number two, she looks about 19.

So those are two things you want to keep in mind when you hear the knowledge drop from her lips.

That she is hot and looks like she's 19.

I'm not 19, by the way, just so you know.

I'm not 19.

Chuck, why did you pick that age in particular?

Because it's legal.

That's exactly what I thought, Chuck, there it was.

There's no lying in me.

That's why we love you, Chuck.

So Kara, if you had to describe what your particular expertise about the brain is, what would you say?

I think that's still evolving.

I think my interest was in brain damage, has been in brain damage.

That's kind of what I want to continue to do.

That's what you learn, because you can't go in and poke somebody's brain and find out what happened.

You gotta wait for stuff to happen accidentally.

Yeah, I mean, you can do models with animals, and I've done some of that.

Non-human animals.

Non-human animals, exactly.

Right, not just guys that play for the Lakers.

But you do, you have to wait until something happens, and sometimes you have to wait until autopsy or at least until you can get good imaging to see what actually did happen in the person.

Right, and so a particular injury, my damage of a certain part of the brain that you never knew had a particular function.

Yeah.

And then a person behaves crazier than they might have behaved before.

And then you've just nailed the spot of the brain for causes and effect, right?

And brain damage for a lot of people, it's like fingerprints.

You want to say that we have classified particular areas that do particular things, and you damage this area, and you have this effect.

But the truth is, nobody has the same brain damage.

Right.

Nobody.

As each other.

It's a very organic thing.

Right, okay.

You could damage the same area and have a totally different outcome.

And is that just because each individual brain has that particular type of makeup?

I mean, the makeup of our brain is that particular?

Well, it's similar brain to brain, but it's very rare that only a very specialized region of the brain would be damaged anyway.

You're going to have other effects.

Well, see, that brings me to ask, because how many, we've got 100 billion nerve cells, brain cells?

Yeah, just the neurons.

Yeah, just the neurons.

I love saying 100 billion.

So let's say that together.

100 billion.

Very Carl Sagan.

Take up the billion out there in that low voice.

Like Sagan.

I like that.

Carl Sagan.

Saganomics.

And so 100 billion nerve cells and brain cells.

And we typically, the naive thought about the brain is that it stores information like a file cabinet and you go and retrieve it.

But recently we've been learning it's much more complex than that, right?

In terms of the storage of information and retrieval, is that right?

Well, I think we used to think that we could just learn discrete packets of information.

You just see something in the world or you experience something through your senses and then it goes to a certain part of your brain and it just lives there until you want to pull it back out.

Right.

It's not like a file, like you said, but really a lot of it is about connections.

It's all about taking something in, connecting it to something you already knew.

Like Facebook.

Exactly.

It's a web.

It's like a social network in your mind.

A neuro network.

A neural network.

Can I de-friend certain parts of my brain?

You drink enough probably.

How to de-friend part of your memory.

Now, Chuck, we put you on assignment earlier.

Yes, you did.

And where I work, I'm at the American Museum of Natural History here in New York City.

I run the Universe part of the museum, which includes-

Which, by the way, is so cool.

If you're ever in New York, you gotta go there.

Oh, thanks for the commercial.

Yeah, so I run the Hayden Planetarium, but now we, the museum, has an exhibit on the brain.

Yes.

And I actually had not had a chance to view it, but we sent you so you could report back to StarTalk Radio on what you found and what others found.

Yes.

We, we made the mistake, I think, of giving Chuck a microphone.

So I'll tell you the irony of this whole piece.

It's the brainless going to a brain exhibit.

Let's see what Chuck tells us from the museum, live on location.

Well, he were, it's pre-taped.

I was live on vacation.

I was live on location.

He was live on vacation.

Check him out.

What is your favorite part of the brain?

The stuff in the brain.

The stuff in the brain.

That's what I need more of.

I need more stuff in my brain because my brain is kind of empty.

What is empty?

Listen, wait.

Rattle my head.

Listen.

Yeah, what does that mean?

Yeah, that's kind of nothing rolling around in my head.

I'm actually a school psychologist.

Really?

So now as a psychologist, do you find that people's experiences and environment or their brain causes them to have psychological problems?

No, experiential learning and environmental learning have an impact, I believe, on brain development and the memories that you retain.

So, how do you explain my mother telling me that something's wrong with me because I ain't right in the head?

You're trying to get a free session.

Help me, Pamela.

I'm on vacation.

Did you learn anything that just totally wowed you?

The fact that your brain tells you everything it makes everything in your body go.

Everything.

Even the things that you take for granted.

Like you just blinked.

I saw you blinked.

I saw you blinked there again.

Your brain told you to do that, right?

Do you know why I'm blinking right now?

I'm afraid you might hit me.

I won't do that.

Thank you.

I can rest easy.

As a neurobiologist, I'm interested to know what your favorite part of the brain would be.

Well, right now, at my age, the hippocampus.

How's that?

Ah, okay.

That would be because the hippocampus is responsible for what?

Memory?

Yes.

You have to use your brain in order to keep it going.

So the brain is like a muscle.

You got to use it?

You have to exercise it.

Use it or lose it.

What was the thing that most impressed you about your own brain that you found out in the exhibit?

I think in relation to short and long term memory that it's sleep that actually transfers memories from short term to long term.

So you look well rested.

No, I'm not.

I'm jet lagged.

Are you really?

Yeah, I am.

Are you from Australia?

I am.

So you've had a long flight.

Yeah.

And did you sleep on that flight?

I only had a very little bit.

So was there anything else that really impressed you?

Something you never thought you'd know about your brain that you found out?

No, I can't remember anything else.

And there you have it.

The short term, long term, you need some sleep.

I need some sleep.

Chuck, just harassing visitors to the Hayden American Museum, Hayden, no, actually the brain exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History.

So in there, we heard about the hippocampus.

So Kara, tell us about the hippocampus.

All about the hippocampus.

Yeah, in one minute about.

I remember first learning about the hippocampus and then teaching my students about the hippocampus.

And I would imagine a hippopotamus walking through my college campus, remembering how to get to class.

That helped me at the time.

Yeah, it's a deeper structure of the brain.

It's kind of underneath the cortex.

And it's involved in memory.

And it used to be the case kind of after a really famous patient, patient HM had his hippocampus damaged when he had a surgery for epilepsy.

Scientists all thought, well, this must be the seat of memory in the brain.

This is the only place where memory is.

Once again, because of some accident, then they know this.

They believe it.

They could look at his brain and say, well, he's kind of missing this area and he can't remember things now.

He can't encode new memories.

What we've found out more recently is that memory is very ubiquitous in the brain.

It's in many parts of the cortex.

And like we said before, the memory of a single thing can be spread around.

It can.

It can.

Not just different things in different places.

But definitely different things.

But the memory of a single thing can, too, because we make associations.

You know, smells help us.

Totally.

You know, whatever.

You know, you're right.

I mean, I was home today at my parents' and my mother made some food.

And it took me back to being in that home when I was like 11 years old.

Yeah.

That's one of the strongest triggers, actually.

It's a very old part of the brain.

Comfort food is not just that it is, but that it has a smell.

Right.

And that it brings comfort.

Yeah, that makes sense.

Definitely.

And food.

Flavor.

Flavor is smell.

The meatloaf is waiting for you outside.

All of this.

All of this makes flavor.

All of this plugs into the brain.

Yeah, but then that plugs into the brain and it helps us recall memories and encode memories.

But really the hippocampus we found is more of kind of a way station.

It's the place where memories can kind of first be encoded and then spread out to other parts of the cortex for storage.

So this sounds like there's a risk of misremembering something if it's got to store one place first and then other places later.

But we get back to that in another segment.

But before we even get there, do you compare the human brain with other brains?

Because I've been reading about this and I learned that the octopus, which is kind of an extraordinary creature for starters, can each limb, each of the eight limbs kind of can operate autonomously without reference to the brain.

This is what I learned about.

Like there's ganglia, like mini brains.

Yeah, mini brains that can make their own kind of decisions.

This is cool and scary.

It's very cool.

You know how dolphins sleep?

I never asked.

Since they have to be underwater, but they're mammals, they have to breathe.

Oh yeah, yeah, yeah.

It's conscious breathing.

So they sleep by one hemisphere going to sleep at a time while the other remains alert.

So they can sleep and still swim to the surface and breathe, but they're sleeping.

Half of their brain is asleep.

So basically they sleep, walk.

They do.

Or sleep, swim.

They have to sleep, walk.

Sleep, swim.

They sleep, swim.

Right.

And how about whales?

I don't know.

I didn't know that.

So they can just shut, they got a little switch and just switching left and right.

Just like we have a switch.

Well, we have a switch for our whole brain to go to sleep.

It'd be interesting to see what different behaviors they're capable of as one half turns off and the other turns on.

Definitely.

Because we have specialization of our brain as our brain halves, don't we?

Or is that just a fiction from the past?

No, we do.

We definitely have specialization in different hemispheres.

That's always, and sort of creatures that are much smaller that I learned about flatworms, that they don't even have a brain.

Oh, thank God, cause you have scared me.

And where does Chuck fit into this evolutionary?

Well, we're running down our first segment.

When we get back, my interview with neuroscientist Oliver Sattler.

Thank We're back, Chuck, nice.

Thanks for being on StarTalk.

Let me reintroduce our guest today.

In from Los Angeles, this is Cara Santa Maria.

Hello.

Did I pronounce your name right, Cara?

Yes, you did.

Thank you.

Thank you for that.

Cara Santa Maria.

Did I write it right?

It wasn't on one of the Columbus ships?

Yes, it was.

It was, good.

Many a nickname growing up.

Yeah.

Nina Pinta.

And so we promised you before the break that we would take you to an interview that I conducted with Oliver Sacks.

He's probably the world's best known neuroscientist.

And if you haven't heard of him, you may have known the movie, The Awakenings.

In fact, that movie was about him.

That was about him.

Robin Williams was playing him.

Okay, I was gonna say, I'm guessing he's not the Robert De Niro character.

Because that would be truly extraordinary.

Let me double check IMDB to make sure.

But yeah, Robin Williams portrayed him in that film.

It was semi-autobiographical.

I think it was done up a little for the movies as well.

But basically, it was a story of his life and breaking in as a neuroscientist.

His latest book, The Mind's Eye, is about how our brain helps to understand what the eyes see.

Because your eyes are the organ unto themselves.

And they just gotta hand it over to the brain, then the brain has to make sense of it.

So this is what's, somebody needed to write a book on that.

And there's gonna be a movie released.

The music never stopped, did that movie come out yet?

I think it already did.

It's already did, it never stopped, it did come out.

That's based on one of his essays called The Last Hippie, which was published in his book and Anthropologist on Mars.

So apparently he's been places, perhaps including Mars.

So that's Oliver Sacks.

And in our first clip, he talks about the things that define your identity and your personality.

And he describes what role the electrical currents in your brain might play in determining that.

But how a super duper electrical current from outside your brain can really mess with it.

Oh man, I think that's what they wanted to do to me.

That's the part of your life we'll get to at another show, Chuck.

Let's just see where Oliver Sacks takes us.

A colleague whom I describe in my book Musicophilia, he is a surgeon here in New York, and in 1994, through a freak accident, he was struck by lightning.

And he had a cardiac arrest.

He was dead for half a minute, or certainly his brain did not get enough blood or oxygen at that time.

He had a sort of strange experience.

He was conscious of being flung back many feet by the thunderbolt, by the lightning which hit him, and then he felt he was floating forward, and he looked down and that he saw his own body with people around him.

And he said, ***, I'm dead.

But then he seemed to sort of move on, and then a sense of ecstasy came on him, and he saw a bluish-white light, and he felt the most wonderful thing in the world was about to happen.

And then he regained full consciousness to find someone doing CPR on him.

But about three weeks after this, he had a strange emotional and musical change.

This man who had never been interested in music developed a sudden passion for classical music, first to hear it and then to play it, and then he wanted to compose it.

And this also went with a mystical feeling.

He felt that God had sent the thunderbolt, but had also arranged for him to be resuscitated, and that he now had a mission to bring music to the world.

Was he religious before this?

Not really.

I think there were some seeds of religion, but these flared up with the experience, either with the psychological shock of being almost killed, and who knows what neurological changes might have happened as he was electrocuted and when his brain didn't have enough blood.

The brain being an organ of electrical current, right?

That's what goes on in the brain.

Yes, absolutely.

There's this chemistry and electricity, and that's it.

And somehow from this comes thought, imagination, spirit, the idea of God and everything else.

Well, anyhow, this man will put a supernatural explanation on this.

However, he is not ignorant scientifically.

In fact, he has a PhD in neuroscience as well.

As a neurologist, it was up to me to put things in more neurological terms, but without in any way upsetting him, devaluing his experience.

And I said, you know, I'm sure this is what you experience and what you believe, but will you allow that something might have happened inside you?

For example, might supernatural intervention make use of existing neurological structures?

And he said, yeah, okay.

And at that point where I suggested that the two were not wholly incongruous, he said he would be prepared to have subtle forms of brain imagery or whatever to see whether we might be able to find the parts of his brain which had perhaps been reorganized somewhat pushing him towards religion and towards music.

Wow.

Yeah.

Okay, I got one thing to ask about that whole clip.

What's that?

Was that a beep?

Yeah, that was StarTalk's first beep.

Leave it to a neuroscientist to get the first beep on the show.

We're cool like that.

You're cool like that.

And we had to beep his quote of someone else.

That's not even him, right?

Right, right.

So that's what that was.

So that's interesting.

So what confidence this person must have to believe that God would strike him dead with lightning, but then rely on someone to resuscitate him so that he would have these magical musical powers and interests.

You know, I'm just going to say, and not to ever devalue someone's religious beliefs or inclinations, you know, normally when God strikes you, he's kind of pissed.

He didn't hit Moses with a bolt of lightning and then say, I want you to take these ten rules down to the people.

No, he said, Moses, come on up here.

I want to talk to you.

You know, man, when God strikes you, there might be a little problem between you and God.

That you haven't really quite figured out yet.

Right.

So, Kara, so our identity, it looks like it can be altered by just sort of an electrical shock.

It can be altered by a lot of things.

You've heard of Phineas Gage?

No.

Phineas Gage?

No.

No, I'm sorry.

A railroad worker.

Certainly.

I mean, 1800s.

Triply not.

But he was, I mean, he's a super important story that most neuroscience hear about.

Is he the one with the spike in the head?

Yeah, he's the one with the spike in the head.

The tamping iron, and it went through his head, and it, you know, blew out part of his frontal lobe.

He stayed alive.

He stayed alive and, you know, dodged infection, which at the time probably would have killed him with an open head injury.

And he was a different person after.

He was like a womanizer.

He cursed all of the time.

He was a big drunk.

Before that, he was a very straight lady.

So those people today have spikes in their head.

You just saved my life.

I got a reason there.

It's like, honey, I'm sorry.

I just have a spike in my head.

Don't you see this spike?

So how about memory?

Presumably, it can not only change you.

Can it bring memory into existence or take it out?

Can it make memory sharper or lose it?

What, brain damage?

It could.

Yeah, actually.

We see these movies.

How about The Bourne Identity?

That's a famous one where he just doesn't know who he is.

But I've never met anyone who never knew who they were.

There are people who don't know who they are.

How many?

I mean, there are people who have dissociative fugue.

I haven't personally.

Dissociative fugue?

Yeah, it's a psychological condition.

And what's that in English?

They dissociate from themselves and then they fugue.

They go away and they don't know why they're where they are.

So you hear these kind of true crime stories of people waking up in a parking lot, nine towns over and they've stolen a car.

And they don't remember any of it.

Oh, like the crime committed in that state of mind.

Yeah, sometimes that's probably not the case, but even Oliver Sacks did write a story about that.

That does happen.

Because he's especially interested in these kinds of.

Bizarre.

Bizarre, a bizarre thing.

And then I was reading that memory begins to decline at age 50.

That's not right.

Tom, that can't be.

Me and NASA, we're both losing our memory here.

Let's go back to Oliver Sacks and my interview with him in his home office in Granite Village, New York.

And in this clip, I asked him about memories, false or real, and how you get them and how you lose them.

Let's see what he tells us.

If you do functional imaging of the brain, it is relatively easy to tell if someone is telling a lie, because it's quite a complex business to tell a lie.

It's easier to tell the truth, but you cannot tell if someone has a delusion.

Because they believe they're telling the truth.

Yeah, whether the belief is well founded or not, if they have the belief strongly and the emotions and the visualized scenes which go with this, and when people say they've been abducted by aliens, they truly believe this.

In a book I wrote, the name of the book is Uncle Tungsten, I mentioned two early memories from 1940 of bombs which had fallen in London.

An older brother of mine confirmed one of the memories.

He said, yes, it's exactly the way you describe it, but as for the other memory, a memory of incendiary bombs in our garden and of my father's attempts to stop it and to douse it with sand and water which didn't work, my brother said, you never saw it.

I said, what do you mean I never saw it?

He said, we were away at the time.

And I said, but I can see it in my mind now.

I can hear the crackling of the flames, the shouting.

I see the figures of my father and brother.

It is so clear in my mind why.

He said, because our older brother sent us a letter.

And he said, you were fascinated by the letter and even obsessed.

And obviously not only fascinated by it, but I internalized it and visualized it.

It also helps if your brother is a good writer.

Right, yeah.

So this is a false memory or a secondary memory.

Is that the same as implanted memories we've heard?

Yeah, yeah, in a way, this is a bit like an implanted memory.

It had been implanted by a good description, which I think probably appealed to me, you know, romantically, it's sort of exciting.

Though I know now that this is a fictitious or secondary or implanted memory, it does not seem to me any different in quality from the genuine one.

And if I had functional MRIs and was asked to recollect these two things, I think one would see pretty much the same areas of the brain, both the visual and emotional areas sort of lighting up.

Yeah, it's cool.

So I think there are two kinds of failures of memory.

One of them is remembering things that never happened.

Right.

And the other one is forgetting things that did.

Yes.

When we come back, we're going to explore what effects drugs have on brain functions.

We're back to StarTalk.

We've got Chuck Nice and Cara Santa Maria in the house.

So in this next segment, we want to talk about, on this program on the brain, we want to talk about other ways the brain can malfunction or function in ways that, differently from how nature intended.

So when I think of this, I think of sort of psychoactive drugs, drugs that people take recreationally or medicinally to alter their state of mind.

Cool.

And I know our special interview guest, Oliver Sacks, he has experimented with drugs and he will tell us about it in some clips coming up.

And so of course, if you're a neuroscientist and medical doctor, you have access to drugs.

And it's just interesting, but why would anyone want to do this?

I mean, I like my brain.

I like when I have deep thoughts about the universe and almost anything that enters the brain alters your ability to have those thoughts.

So I'm just wondering.

And it may alter it in a positive direction.

In a way.

And you'll have deeper thoughts.

Deeper thoughts.

Why would anybody want to take drugs?

No, let me ask you this.

So I don't know anyone who said, here's an equation that I can't solve.

Let me take drugs so I can be more intellectually acute in my ability to solve it.

I've never seen that, ever.

I think it's two prongs.

Are you looking at solving the equation in a very pragmatic way or in a creative way?

Creative mathematics.

Where's my paintbrush?

Here's the answer to the equation.

You really don't think that physics can be very creative.

It can be creative, but in the end, the adjudicator is nature.

It is not an unlimited, infinite tapestry.

And many drugs are found in nature, and we possess receptors in our brains for some of these drugs.

Oh, is that right?

Like what?

Most all of them.

We have cannabinoid receptors in our brains.

Otherwise, it would be neutral to us.

I hear cannabis in that.

Cannabinoid.

Cannabinoid.

That's code for?

Cannabis receptors.

Which is code for?

We also have receptors for PCP in our brain, and we have not yet really found the endogenous chemical that binds to that.

So that's kind of a quandary.

It's a frontier.

Yeah, it's a frontier.

Let's see what Oliver Sacks tells us about his own time in this exploration.

In the early 1960s, like a lot of people, especially on the West Coast, where I lived at the time, I took a lot of drugs.

Uh-oh, now you can't run for office.

No, no, no.

But I really wanted to see what I'd read about other forms of consciousness.

To what extent would the world open for me?

Would it reveal domains, perhaps, of natural or supernatural beauty and meaning?

Well, they certainly opened domains of natural meaning.

On one occasion, since you're an astronomer, I haven't mentioned this, it was back in 67.

I had started seeing patients with migraine.

And one weekend, I took an old book out of the library, written in the 1860s.

A book was called On Megrim.

And then I loaded up pharmacologically.

But instead of giving way to fantasy, I started reading this book.

And the sort of drug ecstasy, coupled with what was in the book.

And I started to feel this is a most wonderful book.

I felt that the neurological heavens were opening for me, and that migraine was shining like a constellation.

One of the people quoted in the book was an astronomer, the young Herschel, who had migraine.

And describing his migraines, he said he felt like an astronomer of the inward.

As I continued to read the book, I thought this is a wonderful, incredible example of mid-Victorian medicine at its best.

But it was written in the 1860s, and now this is the 1960s.

The author of the book was a man called Living, Edward Living.

And I thought who should be the Living of our time?

And there was a very disingenuous clamor of names came to me, followed by a very loud inner voice, which said, you silly bugger, you're the man.

When I came down from that, that sense that I was the man and this was my subject stayed with me, and I wrote my book on migraine, and I never took drugs again.

So in a way, the opening or awakening I had was in that drug experience.

Interesting.

So he takes drugs and decides to read a book rather than jump off a balcony.

This guy is really a scientist.

That's all I got to say.

Anytime you do drugs and you're just like, what should I do?

Crazy sex?

Buy a couple hookers?

I think I should read a book.

You are truly a scientist.

Yeah, that's a whole other state of mind.

Exactly.

Deep within that.

I was doing some homework on this, and I learned that I don't know if you knew this, Kara, that in the 1950s the CIA experimented with LSD to see if they could alter the memories and perceptions for espionage purposes.

I don't know if you knew about that.

Did it seem to work?

I don't know.

The outcome was this.

Everybody the experiment is on ended up following the Grateful Dead.

Actually, so that was in the 50s, and that's what birthed the 1960s.

A lot of in-wall soldiers there, I think.

There it is.

And of course, the psychogenic factors are not unique to Western culture or modern culture.

Native Americans, long ago, well, maybe still.

Peyote.

We didn't get that from a cactus or something.

For your vision quest.

Yeah.

So I find it interesting, but are you suggesting that the people who take these inner trips, that they're somehow, do they function better as people interacting with other people?

There's this movie out now.

What's it called?

The Pill?

No, it's with Bradley Cooper.

It might as well be called The Pill.

So he's a parent.

I haven't seen the movie yet, but I'm told he takes a pill and it actually builds the mental powers and acuity that he has.

I think they're trying to say that once he takes the pill, he's now open to experience everything.

But the truth is, if we didn't have selective attention, we would be less functional.

Significantly less functional.

Selective attention that allows you to not be distracted by...

We have to be able to filter what gets into our heads and stays there.

So people with ADD, they don't have these filters, is that...?

They have less of them.

Less of them.

So it's just like, I'm going to make the incision right below the A-order.

What the hell is that?

Why is there a bunny in the operating room?

Because I'm on Peyote.

So you don't want ADD surgeons.

Yes, that would be bad.

Unless they're medicated.

Well, yeah.

And so also, there are people who have...

What I wonder is that people have deep religious experience.

They see Jesus or Muhammad, whatever it might be.

What parts...

Have people study what parts of the brain are being excited and what visions they might have and whether that's similar to whatever might be stimulated by drugs?

Or are there bodies producing drugs that give them these visions?

The actual visions?

The actual visions.

Well, I think that there are probably a lot of different parts.

I know that there are scientists out there like Andy Newberg, who has written books about religious experience, and he thinks that this is a genetic thing.

It's something that's in all of us.

We have a God gene in our brain that allows us to see that.

I personally disagree with that view.

I don't think that religious experience is something that's always encoded in our brains.

I think it comes from external sources.

But it could be in some people's brains and not others, right?

What's wrong with that?

It could be a genetic trait for some people.

But it could be that that's what whatever's happening in your brain, that's how you choose to describe the experiences in religious terms.

I see, because you have a religious context in which to interpret it.

And if you don't have the religion, maybe it's aliens that you're looking at.

Exactly.

Which is very easy to figure out, because all we have to do is examine your anus.

Is that right?

And if there's no trauma, you have not been aboard a ship.

Is that how that works?

Thanks.

Next time I'm abducted, I will carry that.

So, getting back to my interview with Oliver Sacks, he went on to talk about how you can have these profound visions and what might induce them and what they might mean.

So, let's see.

This is in his home office, Greenwich Village, New York.

Check it out.

I wondered whether one could imagine something one had never experienced.

In particular, whether one could imagine a color one had never seen.

And I built up a sort of pharmacological mountain.

I won't go into details.

And when I was very loaded, this connected my mind with the seventh color of the spectrum, indigo, and the fact that no two people will ever quite agree as to what is indigo or whether there is an indigo.

And I said to myself, at the peak of my experience, I want to see indigo now.

And suddenly, as if thrown by a paintbrush, a trembling pear-shaped blob of indigo appeared on the wall.

And I leant towards it in a sort of ecstasy.

It was a color I'd never seen.

I thought, purely metaphorically, of course, this is the color of heaven.

I thought this is the color which Giotto had tried to get, but never could.

I also thought it's a color which is no longer in the world.

This was the color of the Paleozoic Sea, but has disappeared.

And as I led forward, the blob disappeared.

But I somehow felt that blob not only as luminous, but as numinous.

Numinous.

I had to look up that word, Chuck.

Numinous.

Numinous.

Numinous.

I thought he said numerous.

Numinous, which I believe means of a relating to spiritual experience.

Yes.

Chuck, the Ivy League educated comedian we have here.

That was very poetic, I think, that interview.

It was beautiful.

It was.

Well, he's a beautiful man.

I mean, everything about him.

He's soft spoken and he would never...

You know, some people have like the evil side of it.

You can't even picture that.

And then you have to bleep him in interviews.

Well, I believe him quoting someone else.

That's what that was.

We've got to take a quick break, but we're StarTalk Radio.

This is StarTalk Radio, welcome back.

During the break, Chuck, you commented that you swig Robitussin for what reason?

Okay, here's the deal, because we were talking about pharmacological drugs being used or inducing hallucinations.

And I know that people actually drink Robitussin, prescription strength Robitussin.

You know people who do this?

I know someone who, well, I know somebody who does it.

I've heard that phrasing before.

Seriously.

I have a friend who does it.

Here's why I never do it.

I'll tell you why, very, very quickly, I'll tell you why.

So this guy and I are hanging out, he's drinking a lick or Robitussin.

That's the street name for it, okay?

He starts getting so high that he's hung over, his body's slumped over, and he's calling me Betty.

Now I'm like, two things.

One, I don't know who Betty is, but if she looks anything like me, that's one ugly broad.

Two, I don't ever want to drink anything that makes me think another man is Betty.

Well, period.

That cured you of your Robitussin.

Right.

So, Kara, are there psychometric, psychotropic drugs that are prescribed for any particular reason?

Not to give people hallucinations on purpose, but of course, there are lots of psychotropics that are prescribed.

Anything from ADHD to schizophrenia, to depression, anxiety, all of these disorders require drug treatment if you have drug treatment with psychotropic.

So, it's psychopharmacology is all about getting into your head.

Speed, people take speed on purpose.

On purpose, to help with attention.

To help it.

Let's get back to my interview with Oliver Sacks and see what he talks about, hallucinations.

I'm very interested in hallucinations.

Some of the hallucinations occur with people who are blind and being partly blind myself, I have a few low level hallucinations myself, but they're only really of blobs of color and geometrical figures and things like that.

But it puts people on the spot if they have a hallucination.

Hallucination is not like imagery.

It's like perception.

It seems to come from outside.

You have no sense.

That is inside.

Yeah, that you are generating it or any part of you.

So you hear music, you run to the window, you look outside for the source of the music.

It's only when you can't find a source for the music that you perhaps start to think, there's some part of my brain gone on automatic.

Or you may not think that.

You may maintain a false belief.

One of my old patients was convinced that the patient next door had a phonograph and was putting on the same record again and again.

When Schumann had some music hallucinations at one point, he thought it was divine music.

So Cara, people can have hallucinations.

And if you're religious, you have this sort of inclination to think that it's divine.

If you're not, you just think, others might just think you're crazy.

Right.

Or they might think you're crazy in both cases.

You may think you are crazy personally, or you may not identify those hallucinations as being external.

What is your capacity to judge that you yourself are not of your own mind?

I think it just really depends on the person.

I think that some schizophrenics are aware of their disorder, and they know that they need the Haldol or whatever drugs they take to get through the day.

And I think some have absolutely no idea that they're experiencing hallucinations and delusions.

The voices in my head just told me you are correct.

And so how about the kids?

We're prescribing Ritalin for kids.

That's affecting their brain in some way.

Yeah, yeah, that's what I was mentioning before.

That's speed.

Oh, that is speed, okay.

It's speed, well, it's like speed.

Speed-like.

It's a speed-like drug.

And it does, you know, we don't really know the long-term effects of kids taking these drugs year after year after year.

Because they're the first experiment in this.

They're not adults yet.

That could be a whole other, we could start another decade like the 60s.

We're priming them for that.

Let's see, I think my one last clip coming up with Oliver Sacks, and we speak a little more about hallucinations and find out what he tells us.

Among the many sorts of hallucination are sorts which one may wake with suddenly in the night.

You wake up suddenly and there's a pterodactyl above your head.

These hypnopompic hallucinations, as they're called, are often of giant figures, sometimes frightening figures, sometimes an immense spider, although sometimes of a little man in green, sometimes of an angel.

They may be akin to dreams in some ways, but here you are conscious and the thing is with you in the room.

There's a presence in the room.

It's not entirely easy coming to terms with something like this.

I've actually recently been hearing about a 10-year-old boy who woke suddenly in the night and saw a figure of a tall woman next to his bed who told him she was his guardian angel.

He turned on the light and the figure didn't disappear.

He ran into his parents when he came back.

The figure had disappeared.

Now, this little boy was very disturbed.

He had no particular belief in angels or visions, but something had happened which he could not deny, but could not explain and could not integrate into his world view.

I suspect that visionary experience, whether drug-induced or in dreams or whatever, has played a part in the genesis of everything from folklore to religion.

For example, for some reason, there are physiological reasons for this, Lilliputian hallucinations, so-called, are rather common of little people.

And one finds in almost every culture that there are elves, fairies, trolls, little people.

One wants to say they're not at the sort of lofty level of angels in the heavens, but they do represent another reality.

I think this is almost built into the brain as well as built into culture.

Is he telling us that it's built into my brain that I'll imagine little people when I'm asleep?

Possibly.

Gremlins.

Gremlins are built into our brain.

Well, he's saying he's seeing it across cultures just the same way that we see faces and things that aren't really faces.

We may be predisposed genetically or evolutionarily.

You mean when I look at clouds, I see Abraham Lincoln?

Yeah.

Yeah, and you don't see an alien.

You see a human.

I see a human.

Because that's important for your evolution.

I don't see a lobster.

No, you may if you're dully.

No, but if it is a lobster, I probably won't think lobster.

I think if it really does look like a lobster.

Lobster man.

I'm more likely to say it looks like something familiar to me.

And so what's the limit of the brain?

I can imagine a day where we plug a USB port into your neck and upload or download.

We kind of did that with Watson on Jeopardy a few weeks ago.

A cow.

Are you afraid of Watson's coming or rising up?

Not at all.

Watson knows things.

He has a memory bank.

Well, so do we.

Like we said, but ours is very different.

So why can't he ever be us?

One thing a computer still can't do is recognize an object that's partially occluded.

If you put a picture of a cat that's hiding behind a tree, a computer will never know it's a cat.

And this is a huge project.

Because the tree is in the way.

No, you can see its ears.

You can see its tail.

We know it's a cat.

A computer really has a hard time synthesizing the whole form part.

And it's easy for us.

This is a human perceptual thing that's so easy, and we don't know how it works.

Okay, we gotta end the show there.

You've been listening to StarTalk.

I'm Neil deGrasse Tyson.

And as always, keep looking up.

See the full transcript

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon

Become a Patron

Become a Patron